|

|

|

|

Student's Condensed Guide

Japanese Buddhism & Buddhist Statuary

This is a Side Page. Return to Parent Menu

This page was made especially for students of Japanese Buddhism. It presents everything on one page for easy printout, with links to the most relevant topics and reference notes for further study.

What is Buddhism?

Buddhism originated in India around 500 BCE, but did not arrive in Japan until around 552 CE. Called Bukkyō (Bukkyo) 仏教 in Japanese, Buddhism is a philosophical system of rigorous mental and physical practice that attempts to end all suffering, pain, and karmic rebirth by adherence to strict ethical and spiritual guidelines.

Founded by Gautama Siddhartha, who forsook his royal life, family, and society in a quest to eliminate material desires and mundane concerns. After achieving enlightenment, he was called Shaka Buddha 釈迦如来 (the Historical Buddha). See Guide to the Teachings of Buddha to explore the main tenets of his philosophy.

Buddhism swept quickly (some 1000 years) across Asia, splitting into three main schools as it evolved. It came last to Japan, crossing the sea from Korea around +552. The Mahayana form in particular gained the patronage of Japan’s imperial court and nobility, thus the majority of surviving Buddhist sculpture in Japan today belongs to the Mahayana tradition. Artwork belonging to the Theravada and Vajrayana (Esoteric) traditions is less prominent, but it is nonetheless plentiful. Sects from all three schools are still active in Japan, but Mahayana Buddhism remains the most popular form.

Buddhism remained confined largely to the Japanese nobility and imperial court until the 13th century, but thereafter it spread rapidly among the common people. Despite early conflict with the native Shinto faith, Buddhism soon gained acceptance and developed alongside Shinto in a great syncretic merger, one generally marked by religious tolerance. Elements of Hinduism インド教 (Indokyō), Taoism 道教 (Dōkyō), and Confucianism 儒教 (Jukyō) were also eagerly adopted by the Japanese, as was China’s Zodiac calendar 干支 (Kanshi or Eto). Today, Japanese Buddhism is a rich tapestry of beliefs, rituals, and superstitions that incorporates all these diverse elements.

Why did Japan absorb then assimilate Buddhism?

Buddhism was adopted by Japan’s rulers primarily to establish social order and political control, and to join the larger and more sophisticated cultural sphere of the mainland. Buddhism brought new theories on government, a means to establish strong centralized authority, a system for writing, advanced new methods for building and for casting in bronze, and new techniques and materials for painting. Buddhism’s introduction to Japan in +552 was accompanied by the arrival thereafter of countless artisans, priests, and scholars from Korea and China, with numerous Japanese missions dispatched to the mainland. Japan first learned of Buddhism from Korea, but the subsequent development of Japanese Buddhism and Buddhist sculpture was primarily influenced by China. According to tradition, Buddhism was introduced to Japan in +552 (other sources say +538) when the king of the Korean Kingdom of Paekche (Jp. = Kudara 百済) sent the Japanese Yamato 大和 court a small gilt bronze Buddha statue, some Buddhist scriptures, and a message praising Buddhism. Scholars continue to disagree on the exact date of the statue’s arrival. The Nihonshoki 日本書紀, one of Japan’s oldest extant documents, says the statue was presented sometime during the reign of Emperor Kinmei 欽明 (ruled from + 539 to 571). For details, see Early Japanese Buddhism. In addition, Buddhism represented a superior religious philosophy compared to the shamanistic mountain worship of the indiginous Shinto faith. Not surprisingly, Buddhism gained the patronage of the court, who endeavored to use it as both a political and spiritual tool for building a stronger nation.

One of the first great patrons of Buddhism in Japan was Prince Shotoku Taishi 聖徳太子 (+ 574 - 622). He embraced the new faith and fostered its acceptance as both a superior religious philosophy and a powerful political tool for creating strong centralized governance under the emperor’s guidance. Shotoku (Shōtoku) is credited with constructing numerous temples, and with centralizing state administration, importing Chinese bureaucracy, codifying twelve court ranks, and enacting a 17 Article Constitution that established Buddhist ethics and Confucian ideals as the moral foundations of the young Japanese nation. During his regency, Japanese missions (outside link) were dispatched to China to learn more and bring back valuable Buddhist texts and objects. In addition to court patronage, another reason for Japan’s embrace of Buddhism involved the notion of “building spiritual merit” for oneself and others. Known as Chishiki (知識) in Japanese and translated as “pious contribution.” Originally a Sanskrit term (mitra) meaning “friend” or “companion,” in Japan it came to designate any person who spread the Buddhist teachings in hopes of saving others. Chishiki was a means to accumulate religious and spiritual merit and thus improve one’s own chance of salvation. It came in many forms, from those who founded and maintained temples, to those who devoted their money, land, or efforts to advance the cause of Buddhism. The Chishiki ideal came to prominence with Emperor Shomu 聖武 (Shōmu; reigned +724 to 749) in Japan’s Nara period. Shomu ordered the construction of a giant bronze Buddha statue, one to be financed by the “pious contributions” of devotees, parishioners, and lay people. The “chishiki” ideal meant that the benefits of constructing and maintaining the giant statue would accrue to anyone who participated in the endeavor, no matter how small their contribution. The concept resonated deeply among Japan’s nobility and common people. Even today, the Chishiki ideal remains a major pillar of Buddhist practice in Japan.

WHO’S WHO

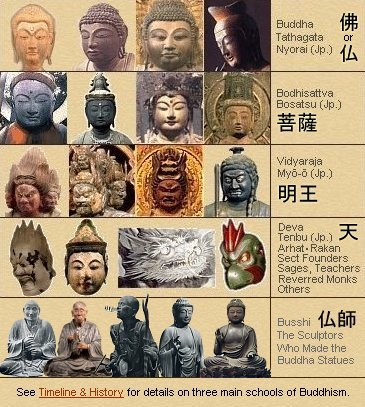

CLASSIFYING BUDDHIST DEITIES

Standard Classification in Japan

Most Deities Originated in India

Click Any Row to Jump to That Deity Group

|

Asuka Statuary. Marked frontality, elongated faces and bodies, crescent-shaped lips, almond-shaped eyes, rigid geometric forms, stock poses, symmetrically arranged and angular folds, as with Tori’s Shaka Triad.

Influences on Period Sculpture. China’s Northern & Eastern Wei 魏 kingdoms (late 4th to 6th centuries)

|

|

JAPANESE BUDDHISM

ASUKA PERIOD +552 - 645

Asuka Period 飛鳥時代. Buddhism was introduced to Japan from Korea and China in the early 6th century. Buddhism met with some initial resistence, but by +585 it was recognized by Emperor Yomei. Soon thereafter, his son Prince Shotoku 聖徳太子 (+574 - 622) fostered the study of Buddhist scriptures and founded various temples -- two of the most important surviving examples are Horyuji Temple 法隆寺 (Hōryūji) in Nara and Shitennō-ji Temple 四天王寺 in Naniwa 浪速 (modern Osaka). Shotoku also adopted Chinese bureaucracy, codified twelve court ranks, and enacted a 17 Article Constitution that established Buddhist ethics and Confucian ideals as the moral foundations of the young Japanese nation.

During Shotoku’s regency, Japanese missions (outside link) were dispatched to China. The capital in those days was located in the Asuka District (part of modern Nara Prefecture). Buddhist images were made primarily by artisans of Korean and Chinese stock who lived in Japan. The period's mainstream works are credited to Tori Busshi 止利仏師 and his followers.

Statuary in the Asuka era seems primitive compared to the classical, baroque, refined, and realistic statuary that followed in subsequent periods, yet it remains captivating and divinely spiritual to modern eyes.

For 50+ photos of extant Asuka-era sculpture, see the Asuka Era Photo Tour. Bronze was the main material used to make Buddhist statues in this age, although wood statues were also created. A few are still extant and very famous. View them here.

|

Hakuho Statuary

Fuller, fleshier figures, more rounded, better balanced sculpture with softer features.

Influences on

Period Sculpture

China’s Northern Qui, Sui & Early Tang Dynasties

|

|

JAPANESE BUDDHISM JAPANESE BUDDHISM

HAKUHO PERIOD + 645 to 710

Hakuhō Period 白鳳時代. Also known as the Late Asuka Period or the Early Nara Period. Highlights include the relocation of the capital to Naniwa 浪速 (modern Osaka) and sweeping governmental changes following the Taika Reforms (Taika-no-Kaishin 大化改新) of + 645 to 646 -- a turbulent time when the court staged a coup to regain supremacy from the powerful Soga 蘇我 clan. Ironically, the pro-Buddhist Soga clan was supported by Prince Shotoku, but after Shotoku’s untimely death, some say murder, the Soga had usurped the power of the throne and forced Shotoku's heir to commit suicide, thus ending the prince’s line. The Soga were defeated in a coup led by the imperial family, after which came the Taika Reforms.

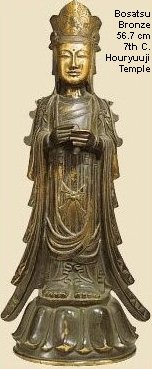

The Hakuho period was marked by the building of many Buddhist temples (which increased ten-fold during the period), and by the academic study of various schools of Buddhism from mainland Asia. Many monks and artisans from Korea and China made the dangerous sea voyage to Japan, and thereafter resided at important temples in the Osaka and Nara areas. Two of the most important surviving temples are Yakushiji Temple 薬師寺 and Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺, both in Nara. The latter was destroyed by fire around +670 and rebuilt. For more on the Hakuho period, see Hakuho Busshi, Asuka Era Photo Tour, and Six Schools, Seven Temples of Nara.

|

Nara Statuary

“Classical” period of statuary; matured sense of Tang artistic styles; fuller body modeling (with attention to front, back, and sides); more natural drapery; greater sense of movement. Influences: Tang China & Korea.

|

|

JAPANESE BUDDHISM

NARA PERIOD +710 - 794

Nara Period 奈良時代. The period begins with the relocation of the capital to Heijōkyō 平城京 (present-day Nara), which was modeled after the Chinese capital of Chang'an 長安 (Jp. = Chōan), underscoring Japan's fascination with China’s Tang culture (Jp. = Tō 唐; + 618-907), art, and architecture. The Nara era was marked by lavish court spending on Buddhist temples, stautes, art, and texts. During the period, Emperor Shomu 聖武 (Shōmu; reigned +724 to 749) ordered the establishment of a nationwide system of provincial monasteries (kokubunji 国分寺) and nunneries (kokubunniji 国分尼寺), with each provincial temple directly answerable to Todaiji Temple 東大寺 (Tōdaiji) in Nara, the head of all state-established temples.

Todaiji also houses the Nara Daibutsu, a gigantic bronze statue completed around +757. Seven temples in Nara served as the centers of academic Buddhist study for the six main sects of Buddhism at the time (see Six Schools Seven Temples of Nara).

The 8th century is considered Japan’s classical period of Buddhist statuary, when Japan perfected its rendition of Tang-style statuary. Features included fuller body modeling (with attention to the entire piece in the round, from front, back, and sides), more natural drapery, and a greater sense of movement. A wide variety of materials were used, including cast metal, wood-core dry lacquer, clay, stone, and wood, but bronze still ruled the roost as the main material for making statuary. During the Nara period, numerous Japanese missions (outside link) were dispatched to China as well, and the Japanese monks on these journeys brought back innumerable texts and images, which were then copied endlessly for the provincial temples. See the Nara Era Photo Tour and Nara Busshi for more details.

JAPANESE BUDDHISM

HEIAN PERIOD +794-1185 Heian Period 平安時代. One of the most fruitful periods of Japanese Buddhism and Buddhist art. During the period, the capital was transfered from Nara to Kyoto, but the powerful Nara temples didn’t relocate, as one of the primary goals of the move was to distance the court from political meddling by the Buddhist monasteries.

The Heian era was a groundbreaking time in Japanese Buddhism and Buddhist art, with two new sects introduced to the original Six Old Sects of Nara. The newcomers were the Tendai 天台 and Shingon 真言 sects, both originating in China, brought back from China to Japan by Japanese priests Saicho 最澄 (Saichō, +766-822, founder of Japan's Tendai sect) and Kukai 空海 (Kūkai, +774-835, founder of Japan's Shingon sect).

Both played monumental roles in the merger of Shinto-Buddhist beliefs, and the development of Esoteric Buddhism (Jp. = 密教, Mikkyō) and esoteric art, the latter exemplified by mandala paintings and statues of wrathful deities with multiple heads and arms.

Religious pilgrimages were instituted during the mid-Heian era as well. Pilgrimages became a lasting practice thereafter.

Japan’s break with China in the 9th century provided an opportunity for a truly native Japanese culture (Kokufū Bunka 国風文化) to flower, and from this point forward indigenous secular art becomes increasingly important. The great sculptural genius of the age was Jocho, whose statue workshop in Kyoto perfected the so-called Wayo 和様 (Wayō) style, which literally means “Japanese Style” statuary as distinct from Chinese-influenced images.

The term baroque is also used for Heian era statuary, but it does not refer to Jocho’s refined and elegant statuary -- rather, it refers to statues of the wrathful Esoteric deities, to the bold and plump statues with exaggerated forms and deep-cut drapery that also appeared during this time.

Wood statuary rises to prominence in the Heian period, surpassing bronze thereafter as the main material for making religious statuary. See Heian Busshi for photos and more details.

|

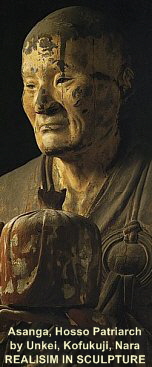

Kamakura Statuary. Bold, emotional, passionate, and realistic sculpture. The “Golden Age” of Japanese Buddhist Statuary. The period’s champion sculptors were Unkei, Kaikei, and the Keiha School.

Realism & Refinement

Influences on Kamakura Sculpture. China’s Sung Dynasty along with Japan’s own indigenous genius

|

|

JAPANESE BUDDHISM

KAMAKURA PERIOD +1185-1332

Kamakura Period 鎌倉時代. This period rearranged the political landscape and gave birth to Buddhism for the commoner. In the political realm, decades of social unrest culminated in the victory of Minamoto Yoritomo 源頼朝 (+1147-1199) and his establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate (Shōgunate) or Bakufu 幕府 in Kamakura city. The emperor and imperial court remained in Kyoto, symbols of culture and art, but political authority shifted to the Shogun (Shōgun 将軍) and military class (Samurai 侍) and remained there for the next seven centuries. In the religious realm, we see the spread of Buddhism among the illiterate commoner and a new spirit of realism in religious imagery.

The period gave birth to new and reformed Buddhist movements -- Pure Land, Zen, and Nichiren -- devoted to the salvation of the common people. These sects stressed pure and simple faith over complicated rites and doctrines. Prior to this, Buddhism was largely the faith of the imperial court, upper classes, and monastic orders. Buddhist temples began responding to the needs of commoners, and Buddhist art became increasingly popularized, for it needed to satisfy not only the commoner but also the new Warrior Class (samurai) who had wrested power from the nobility. For more on the widespread propagation of Buddhism among the masses in the 13th century, see From Court to Commoner Buddhism.

Today, the Jodo (Jōdo) Pure Land 浄土 sects founded by Honen 法然 (Hōnen, +1133-1212) and Shinran 親鸞 (+1173-1262), the Soto 曹洞 and Rinzai 臨済 sects of Zen founded by Dogen 道元 (Dōgen +1200-1253) and Eisai 栄西 (+1141-1215), and the Nichiren 日連 sect (also called Lotus or Hokke 法華) founded by Nichiren 日連 (+1222-1282), remain the bedrock of modern Japanese Buddhism, with millions of followers, both inside Japan and in Western nations.

Kamakura-era Buddhist sculpture and painting portrayed divinities with greater humanistic nuances and personalities, and a new spirit of realism emerged. Among the common folk, the deities Amida, Kannon, and Jizo became popular saviors (Amida for the coming life in paradise, Kannon for salvation in earthly life, and Jizo for salvation from hell). See Kamakura Busshi for more details and photos.

Buddhist Statuary rose to its climatic triumph in the Kamakura Period (12th and 13th centuries), with realism as one of its defining characteristics. After that, the art of Buddhist sculpture fell into decline, overcome by political turmoil, the rise of secular art, the declining influence of institutionalized Buddhism during the Edo-period shogunate, contact with the West, and the rise of Shintoism to state religion in the modern era.

JAPANESE BUDDHISM

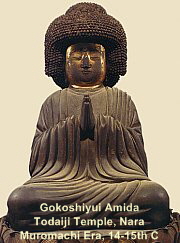

MUROMACHI PERIOD +1392-1573

Muromachi Period 室町時代. The new and reformed Buddhist sects of the prior Kamakura era consolidated their gains, and Buddhism for the commoner thereafter remained a regular feature of Japan’s Buddhist landscape. Pilgrimages to sacred sites devoted to Kannon, to the Ise Shinto shrines, and to the top of Mt. Fuji also became popular. Yoshimitsu 足利義満 (+1358-1408), the third Ashikaga Shōgun, ushered in a brief period of cultural renaissance, highlighted by the reopening of formal trade with China after a lapse of nearly 600 years, the building of great temples and palaces (e.g., the famous Kinkakuji 金閣寺 or Golden Pavilion in Kyoto), and strong patronage of the arts and Zen Buddhism.

|

MUROMACHI CHRONOLOGY

Nanbokuchō Period

Southern & Northern Courts

南北朝時代 +1336-1392

Warring States (Sengoku)

戦国時代 +1467-1568

Muromachi Period

室町時代 +1392-1573

Also known as

Ashikaga Period

足利時代 +1392-1573

Azuchi-Momoyama Period

安土桃山時代 +1574-1615

THE DARK AGE

OF JAPANESE

BUDDHIST STATUARY

|

|

Nevertheless, most of the period was marked by incessant civil war. Fighting lasted until the arrival of the “great unifier,” the feudal warlord Oda Nobunaga 織田信長 (+1534-1582), who marched into Kyoto in +1568 and captured the city. Oda needed a few more years to overthrown the Muromachi Bakufu 幕府, which he achieved with the abdication of the last Ashikaga Shōgun 足利将軍 in +1573. Even so, many of Kyoto’s great art treasures were lost during the fighting, and the powerful Buddhist monestaries suffered greatly thereafter. The Tendai 天台 stronghold at Enryakuji Temple 延暦寺 on Mt. Hiei 比叡 (near Kyoto) was burnt to the ground in +1571 by Oda and the militant monks scattered. So too was the powerful Ishiyama Honganji Temple 石山本願寺 of the Jōdo Shinshu 浄土真宗 (True Pure Land) sect in Osaka, set to flame by Oda in +1580. Nevertheless, most of the period was marked by incessant civil war. Fighting lasted until the arrival of the “great unifier,” the feudal warlord Oda Nobunaga 織田信長 (+1534-1582), who marched into Kyoto in +1568 and captured the city. Oda needed a few more years to overthrown the Muromachi Bakufu 幕府, which he achieved with the abdication of the last Ashikaga Shōgun 足利将軍 in +1573. Even so, many of Kyoto’s great art treasures were lost during the fighting, and the powerful Buddhist monestaries suffered greatly thereafter. The Tendai 天台 stronghold at Enryakuji Temple 延暦寺 on Mt. Hiei 比叡 (near Kyoto) was burnt to the ground in +1571 by Oda and the militant monks scattered. So too was the powerful Ishiyama Honganji Temple 石山本願寺 of the Jōdo Shinshu 浄土真宗 (True Pure Land) sect in Osaka, set to flame by Oda in +1580.

The considerable political power of the entrenched Buddhist monasteries never recovered from this onslaught. They were no longer allowed large landholdings, lost various other economic advantages, and found their connections with the now-powerless imperial court of little value. Unlike the Tendai and Pure Land sects, the Zen denomination rose to prominence and political power during the Muromachi period, with many warriors turning to Zen Buddhism for release. Oda Nobunaga, meanwhile, was betrayed by one of his generals and forced to commit ritual suicide in +1582. But the traitor was soon overthrown by Toyotomi Hideyoshi 豊臣秀吉 (+1536-1598), a loyal Oda ally, who then proceeded to eliminate rivals and succeeded in unifying Japan around +1590. In his efforts to gain control, Hideyoshi issued an edict in +1587 banning Christianity, although this edict was not enforced initally (e.g., Christian missionaries were still entering Japan in +1593). But in +1597, Hideyoshi had 26 Franciscans executed, and laws prohibiting the foreign religion continued unbated into the 1630s. After Hideyoshi’s death, general Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (another loyal Oda ally; +1542-1616) assumed control. In +1603, he founded the Tokugawa Shogunate 徳川将軍, which ruled Japan for the next 250 years from Edo 江戸 (modern-day Tokyo). See Edo section below for details.

Note on Buddhist Statuary. Japan’s art historians portray the Kamakura Period as a great renaissance in Buddhist statuary. In contrast, the Muromachi Period was considered a period of decline, one which might be called the “Dark Age.” Of the 2,609 works of sculpture designated as National Treasures 国宝 or Important Cultural Properties 重要文化財 in Japan, not one piece from the Muromachi period is on the list of National Treausures, and only 90 Muromachi pieces are listed as Important Cultural Properties (and those only in recent decades). The reasons for this sudden decline of sculpture during the blood-soaked Muromachi centuries are hard to explain. More details here. Also see Muromachi Busshi for details and photos of era artists and artwork. Note on Buddhist Statuary. Japan’s art historians portray the Kamakura Period as a great renaissance in Buddhist statuary. In contrast, the Muromachi Period was considered a period of decline, one which might be called the “Dark Age.” Of the 2,609 works of sculpture designated as National Treasures 国宝 or Important Cultural Properties 重要文化財 in Japan, not one piece from the Muromachi period is on the list of National Treausures, and only 90 Muromachi pieces are listed as Important Cultural Properties (and those only in recent decades). The reasons for this sudden decline of sculpture during the blood-soaked Muromachi centuries are hard to explain. More details here. Also see Muromachi Busshi for details and photos of era artists and artwork.

|

NIHON-JI DAIBUTSU

Image of Yakushi Nyorai

Constructed in 1780s

See Edo Busshi for more.

EDO-ERA

CHRONOLOGY

Edo Period

江戸時代 +1615-1868

Tokugawa Period

徳川時代 +1615-1868

Kan'ei Bunka Era

寛永文化 +1615-1651

Kanbun Era

寛文 +1661-1673

Genroku Bunka Era

元禄文化 +1688-1715

Kyōhō Era

享保 +1716-1736

Kansei Era

寛政 + 1789-1801

Kasei Bunka Era

化政文化 +1804-1830

Bakumatsu Era

幕末 +1800-1867

EDO REVIVAL

|

|

JAPANESE BUDDHISM

EDO PERIOD +1615-1868

Edo Period 江戸時代. Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (+1542-1616) gained complete hegemony with his victory over the Toyotomi 豊臣 family in +1615, and thereafter Japan enjoyed over 250 years of peace and prosperity under the leadership of 15 generations of Tokugawa shōguns 将軍 (military rulers of Japan). The military capital was established in Edo 江戸 (modern-day Tokyo), and secular arts of all kinds flourished among the growing merchant classes, military clans, and the wealthy.

The importance of secular art has forever thereafter surpassed that of religious art. Buddhist sculpture continued in a downward spiral, and the influence of institutionalized Buddhism plummeted, for it could no longer compete against the Neo-Confucian policies (imported from China) favored by the Tokugawa shōguns. Indeed, most modern scholars consider Neo-Confucianism to be the keynote philosophy of Tokugawa Japan. It brought renewed attention to man and secular society, to social responsibility in secular contexts, and it broke free from the moral supremacy of the Buddhist monasteries. It also provided a powerful philosophy for exercising national rule.

Society was divided into four main groups -- samurai, peasants, artisans, and merchants -- with relations among them governed by strict hierarchical rules and Confucian virtues of filial piety and loyalty. To further ensure control, the Tokugawa shogunate enforced a seclusion policy starting in the 1630s that banned Japanese from leaving the country, and allowed only the Chinese and Dutch to conduct trade, but only on a limited basis and only at the port city of Nagasaki in Kyushu.

To stop the spread of foreign religions, the Tokugawa shōgun in +1659 ordered all Japanese families to register with Buddhist parishes, forcing everyone to declare an affiliation -- this also helped the government count the population and control tax registers. Many Japanese Christians thereafter went into “hiding.” To conceal their faith, they registered as Buddhist lay people, yet they secretly maintained their faith with clandestine codes and ingenious adaptations. For example, statues of the Virgin Mary (Mother of Jesus) were disguised as the Buddhist deity Kannon (Goddess of Mercy). These images, later called “Maria Kannon,” were made or altered to look like Kannon, but they were not worshipped as Kannon by the “secret” Christians. Many, moreover, had a Christian cross or other icon hidden inside the statue’s body.

Despite the declining fortunes of Japan’s traditional Buddhist monasteries, the Edo period witnessed a great surge in peasant interest in Buddhist talismans, rituals, pilgrimages, and superstitions. Many of these folk beliefs came under severe attack in the ensuing Meiji & Modern periods. The final nail in the Buddhist coffin, however, was the elevation of Shinto to state religion in the Meiji era.

Edo-Era Revival in Statuary

In the Edo period, two wandering (itinerant) monks of great modern fame revived a carving technique known as Natabori 鉈彫 (hatchet carvings, popular from last half of the 10th century to around the 12th century). They were the Buddhist priest Enku (Enkū) 円空 +1632-1695 and the Zen priest Mokujiki Myoman (Myōman) 木食明満 +1718-1810. Nearly all of their extant pieces were carved from a single block of wood and were not hollowed out. This gives their pieces a freshness that is completely different from the refined works of traditional Buddhist sculpture. In modern Japan, their extant statues are highly prized. See Edo Busshi for more photos and details on numerous sculptors of Buddhist statuary in the Edo period.

|

Takaoka Daibutsu 高岡大仏

Metal, H = 15.85 meters

Takaoka City, Toyama Pref.

Construction of this

reproduction began in 1907.

Completed in 1933.

|

|

JAPANESE BUDDHISM

MEIJI PERIOD +1868-1912

At the start of the Meiji Era 明治時代, Japan was forced to end decades of isolation. The "black ships" of Commodore Perry convinced the new Meiji leaders to open Japan's doors to Western culture, commerce, and technology. Japan thereafter enthusiastically entered a race to modernize and thus block the colonization of its islands. In the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the imperial family was moved from Kyoto to Tokyo (formerly Edo), the emperor regained imperial sovereignty from the Tokugawa shogunate, and a new government composed of a small band of samurai and nobles institutionalized Shinto as the new official state religion (one focused on emperor worship) and implemented restrictive policies against Buddhism, Christianity, and other religions. Shintoism was easily co-opted by the government and used to galvanize the nation into building a modern military, administrative, and educational state. Shintoism and Buddhism were forcibly separated, with Buddhism declared a superstitious foreign import. By decree, fiat, and force, the Meiji government proceeded to break up the once-powerful Buddhist estates. Temples were forced by law to cut their Shinto ties, harassed on all sides by new laws and estate taxes, and soon stripped of their lands and artistic treasures. Government attempts to destabilize Buddhism contributed to the anti-Buddhist riots of the late 1860s, when popular sentiment turned against Buddhism, portraying it as a foreign cult of corruption and decadence. In some areas, notably Satsuma 薩摩, raging mobs burned down temples and decapitated statues. These anti-Buddhist riots are referred to as Haibutsu Kishaku (廃仏稀釈), which literally means "Abolish the Buddha, Kill Shakamuni." See Meiji Busshi for more details on the mayhem, plus a review of Meij-era sculptors and statues.

AMERICAN RESCUES JAPAN’S BUDDHIST STATUARY. The great treasures of Buddhist art in Japan were rescued by a young American named Ernest F. Fenollosa フェノロサ (+1853 - 1908). Appointed by the Meiji government to catalog and register Japan’s Buddhist treasures, Fenollosa played a major role in rescuing Japan’s artistic heritage from the ash-heap. He was awarded four times for his efforts by the Meiji Emperor (Meiji Tennō 明治天皇 +1852-1912), receiving his last award in +1890, when the emperor requested a personal audience and bestowed the “Order of the Sacred Mirror” on Fenollosa. More Details Here.

MODERNIZATION OF BUDDHSIM. Many fought hard to retain Buddhism as a feature of modernized Japan. But they did so by denouncing all forms of superstition and by focusing entirely on elements that conformed to Western notions of “religion.” One of the most powerful voices was that of Inoue Enryō 井上円了 (+1858-1919). More Details Here.

|

Built in 1984

Bronze, 21.35 meters

Many giant statues were built in the modern era, mostly to attract tourism, but also as memorials or prayers for world peace.

See Big Buddha for more.

MODERN

CHRONOLOGY

Meiji Period

明治時代 +1868-1912

Taisho (Taishō) Period

大正時代 +1912-1925

Showa (Shōwa) Period

昭和時代 +1926-1989

Heisei Period

平成 (+1989 to today)

|

|

JAPANESE BUDDHISM

MODERN PERIOD (+1912 to Present)

Japan’s rapid modernization and industrialization, and its subsequent colonialization of greater Asia, brought it into direct conflict with Western powers. The result was World War Two, perhaps the most deadly and destructive war in earth history. Japan surrendered soon after the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Its lands were occupied by American forces, its military dismantled, a new constitution imposed by the victors, and the task of rebuilding the nation begun in earnest. The emperor was stripped of all political power and forced to renounce his divine godlike status, although he retained his role as figurehead of the nation. From the 1950s into the 1990s, Japan experienced its so-called Postwar Economic Miracle -- today it is the world’s second largest economy.

Rescuing Japan’s Folk Art (Mingei)

Japan’s rapid pre-war industrialization was accompanied by a massive effort to learn, import, and adapt Western science, technology, and art. But modernization had its costs, for many of Japan’s traditional art forms were quickly overcome by the new fascination with Western forms. Yanagi Soetsu 柳宗悦 (+1889-1961) lamented this development, and coined the term Mingei 民芸 (folk art) in 1926 to refer to common crafts that had been brushed aside by the industrial revolution. Yanagi and his lifelong companions, the English potter Bernard Leach and Japanese potters Hamada Shoji 濱田庄司 and Kawai Kanjiro 河井寬次郎, sought to counteract the desire for cheap mass-produced products by pointing to the works of ordinary crafts people that spoke to the spiritual and practical needs of life. The Mingei Movement sparked by Yanagi was responsible for keeping alive many traditions. Yanagi also founded the Japan Folk Craft Museum (Nihon Mingeikan 日本民芸館) in 1936, which today houses approximately 17,000 items made by anonymous crafts people mainly from Japan, but also from China, Korea, and elsewhere.

Buddhism in Modern Japan

Institutionalized Buddhism never recovered from its setbacks in the Meiji era. It still survives, of course, but growth is stagnant. Its main functions are the performance of funeral and memorial services, the upkeep of the nation’s graveyards, and the sale of amulets and talismans to ward off illness and evil. The many extant temples (and their wonderful art treasures) also serve as living museums of Japan’s religious past, and attract millions of tourists each year. A small group of artists still practice Buddhist sculpting, but their ranks are dwindling. See Modern Busshi (Sculptors) for a review of these artists.

Modern Japanese Buddhism includes 13 traditional sects and nearly 100 sub-sects. Of the thirteen, three originated in the Asuka / Nara eras, two in the Heian era, and virtually all the rest in the Kamakura period. The number thirteen is rather arbitrary, but follows a Buddhist tradition set earlier in China. Curiously, during Japan’s Meiji Restoration 明治維新 (late 19th century), the government officially recognized 13 Shinto sects outside its own state-sponsored shrines (the latter devoted to glorifying the emperor). This is surprising given the Meiji government’s anti-Buddhist policies.

13 Traditional Buddhist Sects (Era Originated)

- Kegon 華嚴宗 (Asuka/Nara)

- Hosso 法相宗 (Asuka/Nara)

- Ritsu 律宗 (Asuka/Nara)

- Tendai 天台宗 (Heian)

- Shingon 眞言宗; also Mikkyo 密教 (Heian)

- Zen Rinzai 臨濟宗 (Kamakura) - Daruma Page

- Zen Soto 曹洞宗 (Kamakura) - Daruma Page

- Zen Obaku 黄檗宗 (Kamakura) - Daruma Page

- Pure Land (Jodo) 淨土宗 (Kamakura) - Amida Page

- Jodo Shin 眞宗 (Kamakura) - Amida Page

- Yuzu-nembutsu 融通念佛宗 (Kamakura) - Amida Page

- Ji 時宗 (Kamakura) - Amida Page

- Nichiren 日蓮宗 (Kamakura) - Kannon Page

Note: Mikkyo 密教 = Esoteric Buddhism,

includes both the Shingon and Tendai sects

Note: See Brief Overview of Buddhist NGOs in Japan, by Jonathan S. Watts, published by the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, Issue 31 / 2, pages 417-428, 2004, Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture.

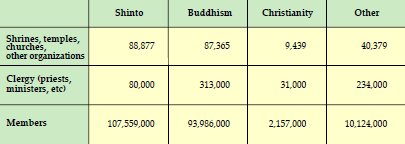

Statistics on Japan’s Religious Organizations

Source: Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, Dec. 31, 2003

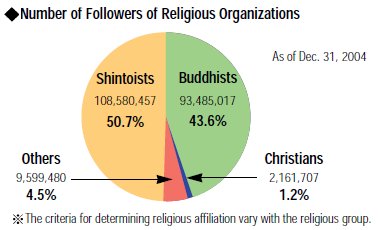

Source: Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, Dec. 31, 2004

According to government statistics, the number of religious groups in Japan at the end of 2003 were:

- Jōdo & Jōdo Shin = 30,000

- Zen = 21,000

- Shingon = 15,000

- Nichiren = 14,000

- Tendai = 5,000

- Shinto Shrines =88,877

- Christian Churches = 9,439

- Others (minimal)

Source: Japanese Ministry of Cultural Affairs

In 2003, over 300,000 Buddhist clergy attended to the needs of their flock, compared to around 80,000 Shinto clergy. Some 85% of Japan’s population claim to be Buddhists, with the largest group (around 25 million people) belonging to the Nichiren sect. However, the number of Japanese people claiming allegiance to either Shintoism or Buddhism exceeded 213 million, nearly 70% greater than Japan’s population of 127.5 million.

The Japanese obviously find no problem claiming simultaneous allegiance to both sides. This is easy to understand, for Shintoism and Buddhism flourished together (sharing deities and sacred grounds) for most of Japan’s recorded history. It was only in Japan’s Meiji Era (19th century) that the government forcibly separated the two camps, proclaiming Shinto to be the state religion (with the emperor a living god), and Buddhism to be a superstitious foreign import. Those militant days have thankfully passed. Modern Japan generally tolerates all faiths, and deities in the Shinto and Buddhist pantheons are worshipped again in tandem, as part of a unified set of protective spirits serving the nation. One can once again find shrines within temples, and temples within shrines.

Even so, the statistics are misleading. Since WWII, and the religious freedoms granted by Japan’s postwar constitution, the traditional Buddhist and Shinto sects have generated little enthusiasm among the people, and growth is stagnant. A recent survey by Zen’s Soto school found that nearly all people claiming a Buddhist affiliation could not name their sect's main temple or founder. Various government surveys reveal consistently that Japan’s population is indifferent to religion -- that the vast majority don’t practice Buddhism or Shintoism on any regular basis. Even though most families are affiliated with a Buddhist sect, this means little, for households were forced to declare an affiliation during the Edo era to help the government count the population and control tax registers. Most people visit shrines and temples as part of annual events and special rituals to commerate major life events, including the first shrine or temple visit of the new year (Hatsumoude 初詣), the annual visit to the family grave during the Buddhist Festival (Obon お盆) in August, the first shrine visit for a newborn baby (Miyamairi 宮参り), the 7-5-3 (Shichi-Go-San 七五三) shrine festival for young children who attain those milestone ages, Shinto wedding ceremonies, and Buddhist funerals. Buddhism, moreover, is associated primarily with funerals and rituals for the dead, and most Japanese learn about Buddhism only after someone dies in their family. In Japan today, both Shinto and Buddhist practice among the common folk has taken on an air of "this-worldly benefits" (concrete rewards now; Jp. = 現世利益, Genze Riyaku). To many Japanese, Shinto and Buddhist faith is primarily involved with petitions and prayers for business profits, the safety of the household, success on school entrance exams, painless child birth, and other concrete rewards now, in this life.

Most Japanese homes still keep ancestral tablets (Ihai 位牌) and altars (Butsudan 仏壇) in their homes, which record the posthumous names of deceased family members and allow families to pay homage to their ancesters. Butsudan appeared in the private homes of Japan's aristocracy at an early date, and became widespread among upper-class families during Japan's Kamakura (+1185-1333) and Muromachi periods (+1392-1568). The placing of ancestral tablets inside the butsudan is generally considered a Confucian influence.

As in the past, Japan’s existing temples and shrines, and their monks and nuns, pay no taxes.

ENGLISH RESOURCES

- JAANUS. Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System. In my mind, JAANUS is the best online database available on Japanese art history. Compiled by the late Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent, it covers both Buddhist and Shinto deities in great detail and contains over 8,000 entries.

- Dr. Gabi Greve. See her page on Japanese Busshi. Gabi-san did most of the research and writing for the Edo Period through the Modern era. She is a regular site contributor, and maintains numerous informative web sites on topics from Haiku to Daruma. Many thanks Gabi-san !!!!

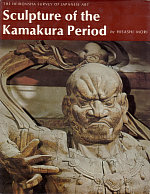

Heibonsha, Sculpture of the Kamakura Period. By Hisashi Mori, from the Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art. Published jointly by Heibonsha (Tokyo) & John Weatherhill Inc. A book close to my heart, this publication devotes much time to the artists who created the sculptural treasures of the Kamakura era, including Unkei, Tankei, Kokei, Kaikei, and many more. Highly recommended. 1st Edition 1974. ISBN 0-8348-1017-4. Buy at Amazon Heibonsha, Sculpture of the Kamakura Period. By Hisashi Mori, from the Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art. Published jointly by Heibonsha (Tokyo) & John Weatherhill Inc. A book close to my heart, this publication devotes much time to the artists who created the sculptural treasures of the Kamakura era, including Unkei, Tankei, Kokei, Kaikei, and many more. Highly recommended. 1st Edition 1974. ISBN 0-8348-1017-4. Buy at Amazon . .

- Classic Buddhist Sculpture: The Tempyo Period. By author Jiro Sugiyama, translated by Samuel Crowell Morse. Published in 1982 by Kodansha International. 230 pages and 170 photos. English text devoted to Japan’s Asuka through Early Heian periods and the development of Buddhist sculpture during that time. ISBN-10: 0870115294. Buy at Amazon.

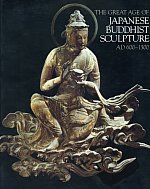

The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture, AD 600-1300. By Nishikawa Kyotaro and Emily J Sano, Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth) and Japan House Gallery, 1982. 50+ photos and a wonderfully written overview of each period. Includes handy section on techniques used to make the statues. The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture (AD 300 - 1300) The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture, AD 600-1300. By Nishikawa Kyotaro and Emily J Sano, Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth) and Japan House Gallery, 1982. 50+ photos and a wonderfully written overview of each period. Includes handy section on techniques used to make the statues. The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture (AD 300 - 1300) . .

- Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art by Ernest F. Fenollosa, published by ICG Muse Inc. ISBN 4-925080-29-6. English. Originally published in 1912, but new edition in 2000. Highly recommended book on Buddhist sculpture in Japan. Although Fenollosa's views on art history are often discredited by modern art historians, this is still an excellent book on Buddhist sculpture in Japan.

- Ernest Fenollosa, "The Coming Fusion of East and West." Harper's New Monthly Magazine. 98, December 1898

- Ernest Fenollosa, The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry. Ed. Ezra Pound. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1936

JAPANESE BOOKS JAPANESE BOOKS

- Comprehensive Dictionary of Japan's National Treasures. (国宝大事典 (西川 杏太郎). Published by Kodansha Ltd. 1985. 404 pages, hardcover, over 300 photos, mostly color, many full-page spreads. Japanese Language Only. ISBN 4-06-187822-0.

- Bosatsu on Clouds, Byodo-in Temple. Catalog, May 2000. Published by Byodoin Temple. Produced by Askaen Inc. and Nissha Printing Co. Ltd. 56 pages, Japanese language (with small English essay). Over 50 photos, both color, B&W. Some photos at this site were scanned from this book. Of particular use when studying the life and work of Jocho Busshi.

- Visions of the Pure Land: Treasures of Byodo-in Temple

Catalog, 2000. Published by Asahi Shimbun. Artwork from Byodo-in Temple. 228 pages, Japanese language with English index of works. Over 100 photos, color and B&W. Some photos at this site were scanned from this book. No longer in print. Of particular use when studying the life and work of Jocho Busshi.

- Numerous Japanese-language temple and museum catalogs, magazines, books, and web sites. See Japanese Bibliography for extended list.

JAPANESE WEB SITES

ONLINE STORE SELLING BUDDHA STATUES

Buddhist-Artwork.com, our sister site, launched in July 2006. This online store sells quality hand-carved wooden statues of many Buddhist deities, especially those carved for the Japanese market. It is aimed at art lovers, Buddhist practitioners, and laity alike. It is not associated with any educational institution, private corporation, governmental agency, or religious group.

First Published Sept. 9, 2007

|

|