|

|

|

|

|

English

|

Japanese

|

Chinese

|

Sanskrit / Pali

|

Korean

|

Tibetan

|

|

Medicine Buddha

Master of Healing

Great King of Healers

Lord Who Cures Illness

Physician of Souls

|

Yakushi Nyorai 薬師如来, Yakushirurikō

薬師瑠璃光,

Dai-i-ō 大医王

|

Yàoshī Rúlái,

薬師如来

藥師璢璃光如來,

大醫王佛, 醫王善逝

|

Bhaisajya, Bhaiṣajya, Bhaisajyaguru, Bhaiṣajyaguru, Bhaiṣajya-rāja, Bhaisajyaguru-vaiduryaprabha

|

Yaksa

Yeorae

약사

|

Menla

Men la

Sangye Menla

Mongol = Otochic

|

|

|

|

|

Last Update May 22, 2014

|

|

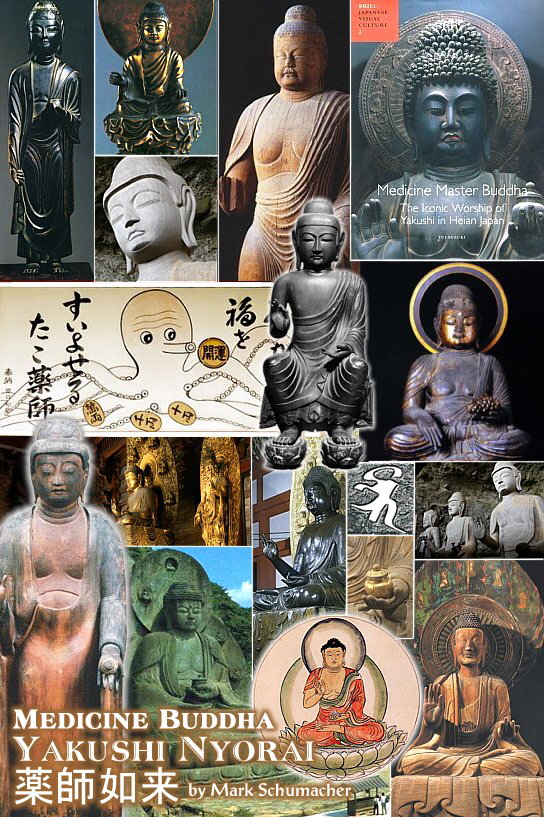

YAKUSHI NYORAI, YAKUSHI TATHĀGATA

Buddha of Medicine and Healing

Yakushi literally means Medicine Teacher

Lord of the Eastern Paradise of Pure Lapis Lazuli

(Jp. = Jōruri 浄瑠璃, Skt. = Vaiduryanirbhasa).

Yakushi’s full name is Yakushi-rurikō 薬師瑠璃光,

meaning Medicine Master of Lapis Lazuli Radiance.

Commonly shown holding medicine jar in left hand.

YAKUSHI HIGHLIGHTS

Made 12 Vows as a Bodhisattva

Two Attendants named Nikkō and Gakkō

Commands 12 Warrior Generals (Twelve Yaksa)

Manifests in Seven Forms (Shichibutsu Yakushi)

Surrounded by Eight Bodhisattva in mandala

One of 13 Deities (Jūsanbutsu) of the Shingon sect

who are invoked in memorial services for the departed.

Origin: Central or Northern Asia

The devotional cult of Yakushi Nyorai (Medicine Buddha) was one of the first to develop in Japan after Buddhism's introduction to the Japanese archipelago in the mid-sixth century. Concrete evidence of his worship on Japanese soil dates from the late seventh century during the reign of Emperor Tenmu (see below images). Originally venerated solely by ruling sovereigns and court elites for their own personal benefits (to cure life-threatening illnesses), Yakushi would later become the central deity in eighth-century rites to ensure the welfare of the entire realm. By the early ninth century, the deity was also called upon to placate vengeful calamity-causing spirits. During the Heian period (794–1185), Yakushi’s cult spread to all regions of Japan, evidenced by an explosive increase in the production of Yakushi images in the ninth and tenth centuries. Hundreds of extant Heian-era Yakushi statues, an exceedingly high number compared to surviving sculptures of other Buddhist deities, attest to his prominence in those days. Most of these Yakushi icons, says scholar Yui SuzukiSOURCE:

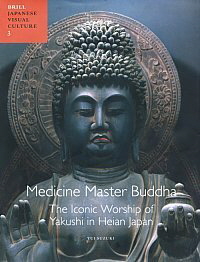

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. , were enshrined in large temples of imperial or aristocratic lineage, but some were installed in private sanctuaries and humble monastic settings far removed from the capital, suggesting that Yakushi worship had already spread to the lower classes. Modern Japanese scholarship has contributed greatly to our understanding of early statues of Yakushi, the styles and techniques employed in creating them, and the linkage of these ancient icons with specific temples. Paradoxically, scholars inside and outside Japan have paid only scant attention to the devotional and ritualistic context of Yakushi worship and the central role of the icon itself in spreading Buddhist faith. This oversight has been thankfully redressed by Yui SuzukiSOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. |

|

WHAT’S HERE

Introduction

Origins and Sutras

Posture (Standing or Sitting)

Mudrā (Hand Gestures)

Medicine Jar / Bowl

Other Yakushi Highlights

Yakushi Repentance Rites

Seven Forms of Yakushi

Yakushi Mandala (Eight Bosatsu)

Grape Yakushi (Budō Yakushi)

Octopus Yakushi (Tako Yakushi)

Resources, Learn More

RELATED PAGES

Yakushi’s Twelve Vows

Yakushi’s Twelve Generals

Yakushi’s Twelve Generals (Tōji)

Yakushi’s 12 Generals (Butsuzō-zui)

Yakushi’s Acolytes Nikkō & Gakkō

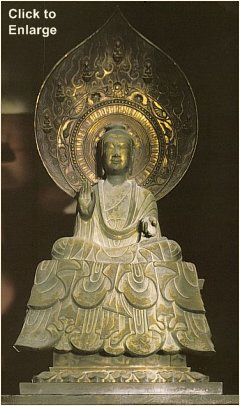

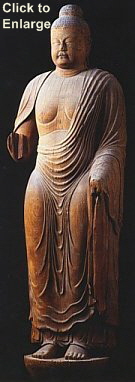

Yakushi Nyorai, H = 191.5 cm, Wood

9th Century, Shin Yakushiji Temple 新薬師寺

Commonly depicted with medicine jar in left hand

and forming ”Fear Not” mudra with right hand.

Photo: Handbook on Viewing Buddhist Statues

SANSKRIT SEED SYLLABLE

Pronounced BEI 佩 in Japanese, Skt. = bhai

MANTRA IN JAPANESE

おん ころころ せんだり まとうぎ そわか

On Korokoro Sendari Matōgi Sowaka

Simplified Trans.= Om. Heal Heal Hail to You

|

|

|

NOTE: This page relies heavily on the research of Yui SuzukiSOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. |

|

JAPAN’S EARLIEST YAKUSHI STATUES WERE MOSTLY SEATED STATUES

|

|

|

|

|

Yakushi Nyorai, Late 7th Century AD

Gilt Bronze, H = 63 cm, Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺 in Nara.

PHOTO: Exploring the Beauty of Japan #11

Magazine. July 9th, 2002. Japanese Language Only

Publisher: 小学館、東京都千代田区一ツ橋 2-3-1

See Yui Suzuki SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242.

|

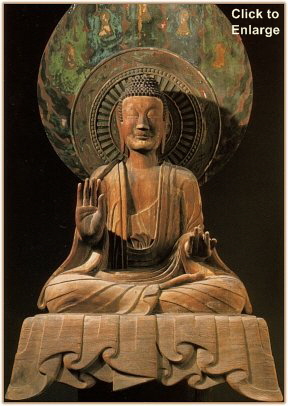

Yakushi Nyorai

Late 7th Century AD, Wood, H = 110.6 cm

Hōrin-ji Temple 法輪寺 in Nara.

PHOTO. Scanned from temple brochure.

See Yui Suzuki SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. (pp. 14-16) for more details about this statue.

|

|

|

|

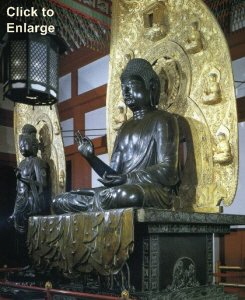

Seated Yakushi Buddha

Yakushiji Temple 薬師寺 in Nara

Late 7th, early 8th century

Bronze, H = 254.7 cm

See Yui Suzuki SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242.

Photo = SERAI サライ magazine, 2005, V 20, p. 125

|

Seated Yakushi Buddha

Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺, Nara Era

H = 244.5 cm, Hollow Dry Lacquer

(Jp. = Dakkatsu Kanshitsu 脱活乾漆)

with gold foil using shippaku 漆箔 method.

Photo by Ogawa Kōzō 小川光三.

|

ORIGINS

Says Matsunami Kōdō 松濤弘道 (b. 1933), a noted Buddhist scholar and one-time chairperson of the Japan Buddhist Federation: "Because a mantra associated with Bhaiṣajyaguru (i.e., Yakushi’s name in Sanskrit) refers to a daughter of a clan that lived in northern Asia, it has been suggested that this Buddha originated, not in India, but among nomadic tribes in northern or central Asia and was later incorporated into Buddhism. A major textual resource for this Buddha is the Sutra of the Master of Medicine (Bhaiṣajyaguru vaiḍurya prabha rāja sūtra)." <end quote by Matsunami Kōdō; see Essentials of Buddhist Images, p. 49>. Note from Site Author: The original Sanskrit manuscript was discovered in the Gilgit area of northwest India (see map). The earliest Chinese translation is attributed to Śrīmitra 帛尸梨蜜多羅 (Jp. = Haku Shirimittara) between 317 and 322. For details, see the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (login with user name = guest). Writes Yui Suzuki (p. 1):SOURCE:

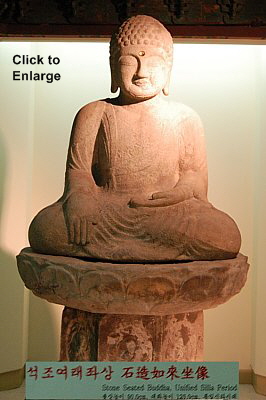

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. “Worship of the Medicine Buddha first developed in Central Asia during the late third century, and was transmitted to China along the Silk Route during the early fourth. From China, it reached other parts of East Asia, including the Korean peninsula. It is from there that the cult entered the Japanese archipelago, taking root firmly by the end of the seventh century.” <end quote>

SUTRAS, SCRIPTURES, TEXTS

|

|

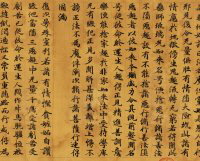

Click to Enlarge

Copy of Xuanzang's

Chinese translation of the sutra entitled "Original Vows of the Medicine Master Tathagata of Lapis Lazuli Light."

Photo from this Chinese site

|

|

Japan’s initial exposure to the “master of healing” came from three sutra (each a Chinese translation based on the original Sanskrit manuscript) transmitted to Japan in the mid-seventh and early eighth centuries. These scriptures describe the powers of this Buddha, the methods for properly invoking the deity, and the benefits to be gained (most notably the curing of earthly illness). They also describe the twelve vows made by Yakushi while he was still a bodhisattva. The oldest extant Yakushi sutra in Japan is dated to 731, although the Nihon Shoki 日本書紀 (Chronicles of Japan; disseminated around 720) contains a passage about the recitation of a Yakushi sutra at Kawaradera Temple. See Nihon Shoki 686.5.24. <source = Yui Suzuki, p. 132SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. > The three main sutra are presented below. The first two were widely circulated in early Japan.

- Chinese name = Yàoshī Liúlíguāng Rúlái Běnyuàn Gōngdé Jīng 藥師琉璃光如來本願功德經. Translated from Sanskrit into Chinese in 650 by Xuanzang 玄奘 (Jp. = Genjō; 602–664) and known as the “Original Vows of the Medicine Master Tathāgata (Yakushi) of Lapis Lazuli Light.” Abbreviated as Yàoshī Běnyuàn Jīng 藥師本願經. In Japan, the sutra is called the Yakushi Rurikō Nyorai Hongan Kōtoku Kyō (abbreviated as Yakushi Hongan Kyō). For more details, see the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (login with user name = guest) or view the Chinese translation at SAT.

- Chinese name = Yàoshī Liúlíguāng Qīfó Běnyuàn Gōngdé Jīng 藥師琉璃光七佛本願功德經. Translated from Sanskrit into Chinese in 707 by Yìjìng 義淨 (Jp. = Gijō; 635–713). The Japanese reading of this sutra title is Yakushi Ryūrikō Shichibutsu Hongan Kudoku Kyō. It is translated into English as the “Scripture on the Merits of the Fundamental Vows of the Seven Buddhas of Lapis Lazuli Radiance, the Masters of Medicine.” Yijing’s version is longer than Xuanzang’s version, indicating an expansion of the latter. The main difference is that Yìjìng’s version features the Medicine Buddha plus six other Healing Buddhas. They are known collectively as Shichibutsu Yakushi 七仏薬師 (literally Seven Buddha of Healing, or Seven Medicine Buddha). See section below entitled Shichibutsu Yakushi 七仏薬師. For more details, see the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (login with user name = guest) or view the Chinese translation at SAT.

- Chinese name = Yàoshī Rúlái Běnyuàn Jīng 藥師如來本願經. Translation from Sanskrit into Chinese in 615 by Dharmagupta 達摩笈多 (Jp. = Darumagyūta; d. 619). Known in Japan as the Yakushi Nyorai Hongan Kyō. For more details, see the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (login with user name = guest) or view the Chinese translation at SAT (T 449).

POSTURE. STANDING OR SITTING?

|

|

Standing Yakushi. Japan. Nara period, late 8th century. Wood, singleblock construction. 165 cm. Tōshōdaiji (former Lecture Hall), Nara. Suzuki believes Saichō modeled his own "prototype" statue after this plain-wood Yakushi image. Its medium (wood), form (standing) and size match those recorded for Saichō's own now-lost work. The Tōshōdaiji statue is attributed to the Chinese monk Ganjin (688–763). Ganjin's influence on Saichō and Tendai doctrine is irrefutable (see Yui Suzuki SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. .

|

|

From the 9th century onward, argues Yui SuzukiSOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. , Yakushi’s cult was spread primarily by the Tendai school as a means to lionize Saichō 最澄 (767-822), the founder of the Tendai school, and to compete with the Shingon school. She says Saichō intentionally chose a standing form of Yakushi (see adjacent image) and this had a special meaning and ritual function that differed drastically from the seated images made in the earlier Nara period. It was Saichō's standing form that was reverently replicated and disseminated to the provinces, and this standing posture, she contends, was meant to represent a "proactive" deity appearing in the worldly realm, rather than a seated Buddha preaching or meditating in a heavenly pure land far removed from ordinary life. This line of reasoning—that standing statues reinforce the image of “active” Buddhist deities bringing “this-worldy” benefits rather than immobile sitting deities removed from earthly concerns—is largely embraced by both Japanese and non-Japanese scholars. Hank Glassman, for instance, author of The Face of Jizō: Image and Cult in Medieval Japanese Buddhism (Univ. of Hawaii Press, 2012), writes (pp. 25-26): “Art historian Mochizuki Shinjō shares Bernard Faure’s opinion that Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are usually immobile, but finds an exception in Jizō and says that his movement is an indication of an active intent to save sentient beings....... he notes that standing statues of Jizō typically have one foot placed in front of the other and that, in paintings, Jizō often has a lotus dais under each foot to accommodate his dynamism.” The lauded scholar John M. Rosenfield, in his Portraits of Chōgen: The Transformation of Buddhist Art in Early Medieval Japan (Brill, 2011), says much the same when talking about Amida statues. To paraphrase Rosenfield: “The left leg is imperceptibly advanced, subtly suggesting movement in the realm of the viewer.” And then, when talking about another Amida statue, he says “the symmetry is broken by a slight contrapposto (the left leg supports the main weight of the body, and the right leg steps slightly forward)....these barely discernible touches of realism serve to link the divine realm to the visible realm of Everyman.” (pp. 162-163).

|

|

|

|

|

Standing Yakushi

Shōjuraikōji Temple 聖衆来迎寺

in Nara. 8th century.

Gilt Bronze, H = 42.5 cm

Photo by Ogawa Kōzō 小川光三

|

Standing Yakushi. Japan, Heian period, 9th century. Wood, singleblock construction, with touches of polychrome. 169.7 cm. Jingoji, Kyoto Prefecture. As Yui Suzuki SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. notes, this is "one of the most impressive specimens of sculpture in the plain-wood style from the early Heian period, appearing in every standard textbook on Japanese art" (p. 89). She adds, "The standing pose.....was an unusual and rare iconographical trait for ninth-century Yakushi icons" (p. 91). The dating and provenance of this statue are still hotly contested. Suzuki argues that this image is intimately connected to Saichō and the Tendai sect (pp. 89–96).

|

Standing Yakushi, 12th Century.

Wood. Joined-block construction. Originally polychromed. H. 160.1 cm. Daikōji Temple, Iwate Prefecture. Says Yui Suzuki SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. (pp 76-78): “The image’s right hand is raised in the fear-not mudra, and the left palm is turned out in the wish-granting gesture. As is common with Heian-period Yakushi images, the Daikōji image holds a medicine jar in its left palm, but based on the awkward positioning of this implement in the hand, Tsuda Tetsuei speculates that the icon may not have held a jar originally.

|

|

MUDRĀ, HAND GESTURES, HAND POSITIONING

Yakushi is typically shown with right hand forming the fear not mudrā (J = seimui-in mudrā 施無畏印; Skt = abhaya mudrā) and the left hand holding a small jar of medicine. But this was not always so. Before the 9th century, Yakushi’s hands were more commonly depicted with the right forming the fear not mudrā and the left forming a variant of the wish-granting mudrā (J = yogan-in 与願印 or segan-in 施願印; Skt. = varada mudrā). This variant—with left hand resting atop leg, palm facing up and middle finger raised—led to the mistaken notion that the earliest images of Yakushi once held medicine jars (jars that were somehow lost in later centuries). This notion is wrong. For details, see Medicine Jar below.

Early statues of Yakushi are easily confused with images of Shaka Nyorai (the Historical Buddha), for statues of both deities are typically depicted with the right hand displaying the fear not mudrā and the left hand displaying the wish-granting mudrā. Nonetheless, some rules of thumb can help to overcome most confusion when trying to identify the image. First, the fingers of Yakushi’s right hand are often slightly curled. Second, in some Japanese sculpture, Yakushi's right hand forms the so-called Yakushi Triple World Mudrā, known as the Yakushi Sangai-in 薬師三界印, in which the thumb touches either the index finger or middle finger. See, for example, the extant Yakushi images from the late 7th century and early 8th century at the Nara-based temples Yakushiji, Hōryūji, and Shōrakuji (photos appear below). Third, unlike images of Shaka, statues of Yakushi from the Heian era or after usually depict the deity holding a jar of medicine in the left hand. In some traditions, the jar is said to contain a miraculous emerald that is capable of curing all earthly illness sickness. Indeed, many Yakushi statues found throughout Japan were commissioned by sick people who were healed. Some of the most famous sculptures of Yakushi Nyorai are at Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺, Yakushi-ji 薬師寺, Ganko-ji 元興寺, Kōfuku-ji 興福寺, and Tōshōdai-ji 唐招堤寺 (all in Nara). Saichō, the founder of Japan’s Tendai Sect, reportedly carved statues of Yakushi, and it is thought that a now-lost standing icon of Yakushi (carved by Saichō himself) served as the “prototype” for repeated replication in Tendai-associated temples across the land (see photo here). <source = Yui Suzuki SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. >

|

EARLY YAKUSHI STATUES WITH TRIPLE WORLD MUDRĀ

|

|

|

|

|

|

Seated Yakushi Buddha

Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺 in Nara.

7th Century, Bronze, H = 15.4 cm.

Right hand forms the Triple World Mudrā

(Yakushi Sangai-in 薬師三界印), in

which the thumb touches either

the index finger or middle finger.

Photo by Ogawa Kōzō 小川光三.

|

Seated Yakushi Buddha

Shōrakuji Temple 正暦寺 in Nara.

8th Century, Bronze, H = 28 cm.

Right hand forms the Triple World Mudrā (Yakushi Sangai-in 薬師三界印), in

which the thumb touches either

the index finger or middle finger.

Photo by Ogawa Kōzō 小川光三.

|

Seated Yakushi Buddha

Yakushiji Temple 薬師寺 in Nara

Late 7th, early 8th century

Bronze, H = 254.7 cm

See Yui Suzuki SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242.

SERAI サライ magazine

2005, V 20, p. 125.

|

|

NOTE: It is worth sidetracking at this point to discuss the mudrās of early Japanese Buddhist statuary. In many cases, the fear not mudrā and the wish-granting mudrā were utilized for various Buddha deities. To paraphrase JAANUS: “In the iconography of Japanese Buddhism, images with the right hand displaying the semui-in (fear-not mudrā) and the left hand displaying the yogan-in (wish-granting mudrā) are regarded as representing the general style for images of the Tathāgata (the Nyorai, the Buddha), and this type is termed the Tsūbutsugyō 通仏形 (lit. "form common to Buddhas"). Hence the semui-in is not restricted to images of Shaka, but is also widely used as the mudrā of Yakushi, Miroku, and Fukūjōju in the Diamond World Mandala. This mudrā is thought to have its origins in an event that took place during the life of the Historical Buddha (Shaka). The malevolent Devadatta, wishing to kill Shaka, released on him an elephant maddened with alcohol, but the elephant was struck by Shaka's spiritual power and fell prostrate before him. In order to emphasize Shaka’s greatness, however, extant representations of this episode in India depict Shaka larger than the elephant, and as a result his right hand is often shown with the five fingers extended and the palm turned downwards as if to stroke the elephant's head. The origins of this Shaka are not necessarily accepted by contemporary art historians.

|

|

MEDICINE JAR, MEDICINE BOWL

Yakushi's iconic medicine jar (yakko 薬壺) is his defining characteristic or symbol (sanmaiya gyō 三昧耶形), but this was not always so. In the beginning, writes Yui Suzuki (p. 21): Yakushi's iconic medicine jar (yakko 薬壺) is his defining characteristic or symbol (sanmaiya gyō 三昧耶形), but this was not always so. In the beginning, writes Yui Suzuki (p. 21): SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. : "Yakushi images from the Nara period and earlier typically do not hold medicine jars.” Later, on page 38, she adds that "the two most important Yakushi sutras in Japan.....make no mention of this implement. Most Yakushi images from the Heian period and later, however, hold a medicine jar in the left palm." This new iconic feature, says Suzuki, was probably introduced to Japan in the ninth century via the Yakushi Nyorai Nenju Giki 薬師如来念珠儀軌 (Ritual Manual for Invoking the Buddha Yakushi). The scripture was translated into Chinese sometime in the eighth century. A look at Japan’s most treasured Buddhist sculptures is illuminating. Of the two hundred fifty-four Yakushi sculptures designated in modern times as Japanese National Treasures or Important Cultural Properties, nearly two hundred hold a medicine jar or bowl. But, in some cases, the jar was added in later centuries. Suzuki also remarks in her introduction (p. 2) that contemporary English-language art-history textbooks only discuss one or two of the 254 extant Yakushi images designated as cultural treasures. Among these surviving Yakushi statues, thirteen are National Treasures and two hundred forty-one are Important Cultural Properties—a number exceeded only by statues of Amida Buddha.

OTHER YAKUSHI HIGHLIGHTS

- This-worldly benefits. From the beginning, Yakushi was invoked in Japan for “this-worldly benefits” (dubbed genze riyaku 現世利益 by scholars) rather than for metaphysical benefits, such as universal truth and transcendental wisdom. This mindset arose from various sources. First, when Buddhism entered Japan from Korea in the mid-sixth century, it was introduced as a religion that rewarded commitment with material benefits. Second, Japan’s initial exposure to the “master of healing” came from two sutras (translated from Sanskrit into Chinese) transmitted to Japan in the mid-seventh and early eighth centuries. Both scriptures contain ritual instructions for petitioning Yakushi to cure earthly illness. Third, the notion of “this-worldly benefits” has been a pivotal and normative theme throughout Japan’s religious history. Yakushi, in his role as savior from earthly sickness and suffering, was one of the first Buddhist deities to be systematically enlisted by Japan’s ruling classes and religious orders.

- Tendai School Influence. In the eighth and ninth centuries, the majority of state-sponsored provincial temples enshrined Yakushi as their principal icon. The state bureaucracy relied predominantly on Yakushi repentance rites to protect the welfare of the nation. At the same time, itinerant monks and local elites in distant provinces helped popularize Yakushi faith. Yui Suzuki

SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. provides ample evidence of these developments, but not extended discussion, for such topics are secondary to her goal, which is to prove that Yakushi’s cult was spread primarily by the Tendai school as a means to lionize Saichō and to compete with the illustrious Kūkai (774–835), the patriarch of Shingon Buddhism. Suzuki writes that Yakushi’s spread was primarily controlled by and aimed at the elite. She says little about Yakushi’s eventual reception by common folk or the deity’s diminished role in the post-Heian religious matrix, which emphasized Buddhism for the commoners.

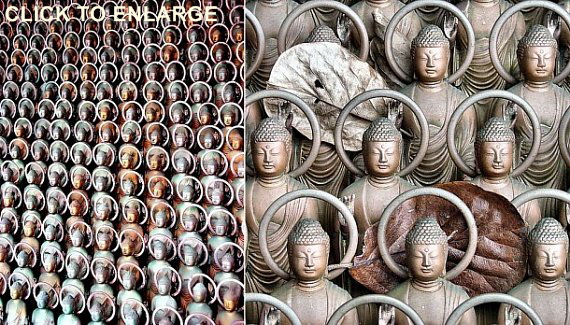

- Cures Eye Ailments. The Tendai school played a key role in spreading the still-popular belief that Yakushi is adept at curing eye ailments. The story originated in the Nanbokuchō period (1336–92) and involves the Tendai monk Seigan 清眼僧都 (d. 1379) and his eye clinic at the Tendai temple Myōgen-in 明眼院, Aichi Prefecture. According to legend, Yakushi appeared to Seigan in a dream and promised to reveal the secrets of healing eyes. The next morning, Seigan discovered the medical text Kanbō-igaku 漢方医学 in the temple that enabled him to successfully treat people suffering from eye afflictions. Seigan's book contributed greatly to the development of ophthalmology in Japan in later centuries.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE. Ichibata Yakushi Temple 一畑薬師 in Izumo (Shimane Prefecture) houses more than 8,000 miniature statues of Yakushi. Devotees come here to pray for relief from eye problems and other ailments. They purchase one of these small bronze figurines (H = 24 cm, cost = $300), write their prayer on a paper slip, insert the slip into the statue, and leave the statue here in the hope that Yakushi will grant their wish. Photos courtesy of More Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan. View the temple's J-site by clicking here. Also see Gabi Greve’s Amulets for Eye Disease.

- Twelve Generals as Attendants. Yakushi Nyorai is protected and surrounded by the Jūni Shinshō (Twelve Generals), ferocious warriors said to represent the Twelve Vows of the Yakushi Nyorai.

- Other Attendants. Yakushi is commonly flanked on the left by Nikkō (Sunlight Bosatsu) and on the right by Gakkō (Moonlight Bosatsu). Yakushi is said to radiate blue light to help sentient beings achieve enlightenment, and thus is commonly associated with other light beings, including Nikkō, Gakkō, and Dainichi Nyorai (Cosmic Buddha, Great Sun Buddha, the Solar Buddha).

- Memorial Services for the Dead. Yakushi is one of the Thirteen Deities (Jūsanbutsu 十三仏), who preside over the memorial services after one’s death in Shingon rituals. In this role, Yakushi presides over the crucial service on the 49th day following death.

- Paintings and Madala Devoted to Yakushi Buddha. To be discussed in future updates.

|

|

|

|

Yakushi Nyorai - Stone

Dongguk University Museum, Korea.

Dated to the Unified Silla Period (668-935).

Photo by Mark Schumacher.

|

Yakushi Nyorai - Stone

Dongguk University Museum, Korea.

Dated to the Unified Silla Period (668-935).

Photo by Mark Schumacher.

|

|

Yakushi Triad (Yakushi Sanzon 薬師三尊) at Kakuonji Temple, Kamakura. ICA.

Nikkō Bosatsu on left (to your right) and Gakkō Bosatsu on right (to your left).

Nikkō (Sunlight) and Gakkō (Moonlight) statues attributed to sculptor Chōyū. Dated to 1422. H = 149.4 cm.

Inscription found in head of Nikkō statue says it was carved in 1422 by local sculptor Chōyū.

Central Yakushi image: H = 181.2 cm. Head dated to Kamakura Period and body to Muromachi Period.

The original central statue (attributed to Unkei) was destroyed in a fire in 1251 and remade in 1263.

The hanging vestments (hōesuikashiki 法衣垂下式), the large rahotsu 螺髪 (hair on head in spiral curls),

the facial features, and the slender fingers clearly reflect the influence of China’s Sung period (Sōdai 宋代).

These features also suggest that the Kamakura Busshi wanted to be independent from Kyoto culture or to rival it.

<Sources: Kondo Takahiro; Kakuonji Temple; Photo from magazine 日本の仏像, 2007/10/25, No. 19 (Kondansha).>

Ryūganji Temple 龍岩寺, Ōita Prefecture (long considered a sacred place of mountain worship).

Circa 12th century, camphor wood, sitting, each approximately three meters in height.

For an English-language video of Oita Prefecture’s religious treasures, see our Video Page.

|

Yakushi Nyorai - Modern amulet

shaped in the form of a praying hand.

Photo by Mark Schumacher.

|

|

Yakushi Keka Ceremony 薬師悔過 Yakushi Keka Ceremony 薬師悔過Says JAANUS: “Keka 悔過 is a term used in Buddhism meaning repentance of one's sins, and refers to the chanting of prayers to various Buddhist deities to express repentance. When the ceremony is addressed to Yakushi, it is known as Yakushi Keka. A very early example of the Yakushi Keka ceremony took place in the year 747, when prayers were said for the Emperor Shōmu's 聖武 recovery from illness. The ceremony itself consists of reciting repeatedly the name of Yakushi Nyorai, and is said to have a magical quality because it is always carried out at night. It was very popular in the 8th and 9th centuries, as it was believed to silence the unquiet spirits of those who had fallen in political turmoil.” <end JAANUS quote> Says The Big Book of Reiki Symbols: “During the rituals of Yakushi Keka, hunting was stopped, captured animals were freed, and sometimes even wars interrupted as an offering to Yakushi Nyorai. The ritual has the effect of quickly healing diseases that normally are incurable without some sort of miracle. On the national level, wars were ritually ended in order to prevent epidemics and natural catastrophes with the power of Yakushi Nyorai. To intensify the light-filled healing force of the sun, magical candle rituals were simultaneously performed in the Tendai School of Esoteric Buddhism for Yakushi Nyorai and Dainichi Nyorai.” <end quote> Japan’s Rubbing TraditionStatues of Yakushi within easy reach of believers are rubbed smooth. People rub part of the statue (knees, back, head), then rub the same part of their body, praying for Yakushi to heal their ailments (e.g., cancer, arthritis, headaches). The same “rubbing tradition” exists for Daikokuten (one of the Seven Lucky Gods of Japan), for Fure-ai Kannon, and for Binzuru (the most widely revered of the Arhat in Japan). Statues of these deities are usually well worn, as the faithful rub the part of the effigy corresponding to the sick parts of their bodies. All three, along with Yakushi, are reputed to have the gift of healing.

|

|

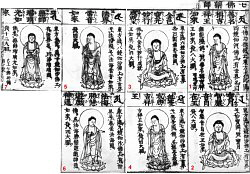

Click to Enlarge

SOURCE: Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙

"Collected Illustrations of Buddhist Images."

Published in 1690 (Genroku 元禄 3).

|

|

Shichibutsu Yakushi 七仏薬師

Seven Forms of YakushiSeven Buddha of Healing

Seven Manifestations of Yakushi The Shichibutsu Yakushi (Seven Yakushi) appear in the Sutra on the Merits of the Fundamental Vows of the Seven Buddhas of Lapis Lazuli Radiance, the Masters of Medicine (藥師琉璃光如來本願功德經), which was translated into Chinese in 707 by Yìjìng 義淨 (Jp. = Gijō; 635–713). Says JAANUS: “The seven are said to reside in realms to the east of our world. They were thought to be efficacious in appeasing the revengeful spirits of fallen political figures implicated in social calamities. In Japan they are represented either by seven independent images or, more frequently, by six or seven figurines attached to the halo of Yakushi sculptures. Popularity and worship of the seven peaked in the late 8th to 9th centuries. Today the ritual service dedicated to them -- the Shichibutsu Yakushi-no-hō 七仏薬師の法; first recorded to have been performed by Tendai prelate Ennin 円仁 in 850) -- survives only in the Tendai 天台 sect, where it is counted as one of the four major rituals (Shika Daihō 四箇大法) of the "Mountain School" Sanmon 山門 or Mt. Hiei 比叡 branch.” <end JAANUS quote> The seven are:

- Zen Myōshō Kichijō-ō Nyorai 善名称吉祥王 (virtuous name, king of happiness)

- Hōgatsu Chigen Kō-on Jizai-ō Nyorai 宝月智厳光音自在王

(precious moon, majesty of wisdom, luminous sound, independent king)

- Konjiki Hōkō Myōgyō Jōju 金色宝光妙行成就

- Muyu Saishō Kichijō 無憂最勝吉祥

- Hokkai Raion 法海雷音

- Hokkai Shōe Yuge Jinzū 法海勝彗遊戯神通

- Yakushi Rurikō 薬師瑠璃光 (the full name of Yakushi Nyorai)

|

|

|

1. Zen Myōshō Kichijō-ō

善名称吉祥王

|

2. Hōgatsu Chigen Kō-on Jizai-ō

宝月智厳光音自在王

|

3. Konjiki Hōkō Myōgyō Jōju

金色宝光妙行成就

|

|

|

|

4. Muyu Saishō Kichijō

無憂最勝吉祥

|

5. Hokkai Raion

法海雷音

|

6. Hokkai Shōe Yuge Jinzū

法海勝彗遊戯神通

|

|

|

|

7. Yakushi Ruriko 薬師瑠璃光

|

Source of Black/White Drawings: Zōho Shoshū Butsuzō-zui 増補諸宗仏像図彙 (Enlarged Edition Encompassing Various Sects of the Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images), published in 1783. It is the expanded version of the Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙, the "Collected Illustrations of Buddhist Images," first published in 1690. One of Japan's first major studies of Buddhist iconography. Hundreds of drawings, with deities classified into approximately 80 (eighty) categories. Modern-day reprints are available for purchase at most large Japanese book stores, or click here to purchase online.

|

|

|

|

|

The Seven Yakushi. 13th century. Wood, single-block construction. H. (central seated Yakushi 54.3 cm; H. (six standing Yakushi) 37.9–39 cm. Matsumushidera, Chiba Prefecture. Yakushi's continuing popularity in Heian religious culture was fueled by a Tendai-derived esoteric rite involving seven forms of Yakushi. Says Yui Suzuki SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. : "These extant images are ritually linked to a set of seven Yakushi icons that were once enshrined in Enryakuji’s Central Hall (p. 105)........the Shichibutsu Yakushi rite remained a private practice reserved exclusively for the elite, performed by Tendai ecclesiastics for their courtly patrons. Practice of the Shichibutsu Yakushi rite never spread to the lower echelons of society, which explains why so few icons remain extant “(p. 123). In a different publication, Suzuki says: “The specific iconography of Shichibutsu Yakushi was not clearly established nor was its theological concept precisely defined in Nara and early Heian. Japanese Buddhists have long recognized these ambiguities, nor have they ever resolved them. In the Tendai and Shingon iconographical and ritual manuals Asabashō and Kakuzenshō, respectively, both of the Kamakura period, these interpretational differences still appear. The compiler of Kakuzenshō notes that the Shingon school considered Shichibutsu Yakushi to be Bhaiṣajyaguru plus six differing manifestations. Shōchō, the compiler of Asabashō, takes a more ambiguous stance, stating that Shichibutsu Yakushi could be interpreted either as six manifestations of the one Yakushi or as seven different Yakushi. In the latter half of the Heian period the Tendai school began making seven mutually distinctive statues of Yakushi as a set for use in the Esoteric Rite of Shichibutsu Yakushi, but there is no evidence for this in the Nara or Early Heian period.” (SOURCE: Pages 20-21, The Aura of Seven: Reconsidering the Shichibutsu Yakushi Iconography, Archives of Asian Art, Volume 60, 2010, pp. 19-42 (Article). Published by University of Hawai'i Press. Read story at JSTOR.Says the Healing Touch website: “Some Sanskrit and Chinese texts describe seven ’bodies’ or emanations that Bhaisajyaguru (Yakushi) can assume during his functions as a healer. One of these emanation bodies (keshin 化身) is sometimes considered as an independent deity in Japan -- known as Zen Myōshō Kichijō-ō Nyorai, who is often confused with Yakushi Nyorai. The emanations are usually represented above the image of Yakushi or in the aureole. They are usually seated and display various gestures. They are sometimes just represented by their seed syllables, written in Sanskrit Siddham characters.” <end quote>

|

|

YAKUSHI MANDALA. Eight Bodhisattva Surrounding Yakushi

Besides Yakushi’s twelve warriors, his two acolytes Nikkō & Gakkō, and his seven manifestations, Yakushi Nyorai is flanked by eight bodhisattva in the Yakushi Hachibosatsu Mandala 薬師八菩薩曼荼羅 (Eight Bodhisattva Yakushi Mandala), which is used in rituals of Japan’s Shingon 真言 sect. <source JAANUS> The eight appear in the 7th-century Yakushi Sutra 藥師琉璃光如來本願功徳經, aka the Sutra of the Master of Medicine (Bhaishajyaguru-vaidurya-prabha-raja-sutra). The eight are:

- Monju 文殊, Skt. = Mañjuśrī

- Kannon 観音, Skt. = Avalokitêśvara

- Mujini 無盡意, Skt. = Akṣayamati. Says the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (sign in with user name = guest): “Inexhaustible intention, or meaning, name of Akṣayamati, a bodhisattva to whom Śākyamuni is supposed to have addressed the Avalokitêśvara chapter in the Lotus Sutra. This bodhisattva is able to observe and comprehend all of the actions of cause and effect (Skt. aparuṣā). [法華經 T 262.9.56c3] ” <end quote>

- Seishi 勢至 or 得大勢至, Skt. = Mahāsthāmaprāpta

- Miroku 弥勒, Skt. = Maitreya

- Yaku-ō (Yakuo, Yakuō, Yaku-o) 薬王, Skt. = Bhaisajyaraja, Bhaiṣajya-rāja; Chn. = Yàowáng (Yaowang) Púsà; the king of medicine; one of two brothers in retinue of Amida Nyorai; represents purifying power of sun; in paintings, typically shown holding willow branch; closely related to Yakushi Nyorai; elder of two brothers (see Yaku-jō below), the first to decide on career as Healing Bodhisattva; convinced younger brother to adopt same course; one of the twenty-five (25) Bodhisattva who accompany Amida from the heavens to the death bed and then lead the deceased back to Amida's Western Paradise or Pure Land..

- Yaku-jō (Yakujo, Yakujō, Yaku-jo) 薬上, Skt. = Bhaisajyasumudgata, Bhaiṣajyasamudgata; Chn. = Yàoshàng (Yaoshang) Púsà; superior physician; one of two brothers in retinue of Amida Nyorai; represents the purifying power of moon; in paintings, typically shown holding willow branch; closely related to Yakushi Nyorai; younger brother of Yaku-ō (see above); one of the twenty-five (25) Bodhisattva who accompany Amida from the heavens to the death bed and then lead the deceased back to Amida's Western Paradise or Pure Land.

- Hodange 宝檀華 or 寶檀華 -- Editor’s Note. Need to find Sanskrit name.

NOTE: These eight show the faithful the road to Amida Buddha’s paradise. There is a sutra named Kan Yaku-ō Yaku-jō Ni Bosatsu Kyō 觀藥王藥上二菩薩經 that presents Yaku-ō and Yaku-jō as the King of Medicine (Yaku-ō) and the Superior Physician (Yaku-jō). These two are brothers in the retinue of Amida Nyorai. The elder (Yaku-ō) was the first to decide on his career as a Bodhisattva; he convinced his younger brother to take the same course. The two are sometimes portrayed as Pure-Eyed and Pure-Treasury. As a pair, they may represent diagnosis and treatment.

Yakushi Nyorai Triad - Treasure of Chusonji, Late Heian Era

Photo courtesy of 日本の実をめぐる (週刊) No. 35, 中尊寺

88-Temple Pilgrimage in Shikoku 88-Temple Pilgrimage in ShikokuEven today, Yakushi is one of the most cherished Buddhist figures in Japan. Among the 88 temples on the well-trodden Shikoku Pilgrimage, 23 are dedicated to Yakushi, second only to the 29 sites dedicated to Kannon (Goddess of Mercy). Below text courtesy of www.asunam.com. “The second major deity among the 88 temples of the Shikoku Island Pilgrimage is called Yakushi Nyorai in Japanese. Yakushi made twelve vows or resolutions, the seventh one being the resolution that he would disperse the illness of any person who called upon his name. ’If my name be called for, I will cure any sick person, whose body and soul shall instantly feel tranquil and free from a sickly feeling.’ He is assisted by his two trusted attendants Nikkō & Gakkō, and also has under his jurisdiction twelve divine generals (Jūni Shinshō), who represent his twelve great vows. He is many times (and most popularly) portrayed carrying a pot of medicine in one hand, and it is from this pot that he dispenses healing medicines. These medicines heal both the sickness of body and the sickness of mind. Yakushi Nyorai is not depicted in the Vajaradhatu (Kongokai) Mandara, nor in the Garbhadhatu (Taizokai) Mandara. In Tibetan images, he is depicted beautifully in his own Mandala, aptly called “The Medicine Buddha Mandala.” <end quote>

|

Yakushi Nyorai, Late Nara period.

Toshodai-ji Temple, H = 340 cm.

Mokushin Kanshitsu 木心乾漆.

Wood-core dry lacquer statue.

Photo courtesy this J-site.

|

|

Yakushi-ji Temple Yakushi-ji TempleBelow text adapted from: Japan Nat’l Tourist Org. Yakushi-ji Temple, adjoining Tōshōdai-ji 唐招提寺, is the temple founded by Emperor Temmu in the 8th century, to pray for the recovery of his wife, the Empress Jito, from a life-threatening disease. In a strange twist of fate, the Emperor died, and the temple was finished by the Empress. The magnificently decorated main hall was at one time called "the Dragon's Palace on Land". The East Tower (Tō-tō) in the precincts is the original structure, which has been preserved ever since its foundation and is the symbol of Nishi-no-Kyo. This famous temple, one of the Seven Great Temples of Nara and the headquarters of the Hossō sect, was constructed in 698 AD in another section of Nara and moved to its present location in 718. The temple suffered many fires and was almost completely destroyed during the civil disturbances of the 15th century. The famous East Pagoda survived as a remarkable example of the art of the Hakuho Period. The pagoda has intervening roofs called mokoshi between each floor, and thus appears to have six stories. The present Kondo (Main Hall) was painstakingly rebuilt in 1976 according to the original design and contains a National Treasure called the Yakushi Trinity. The central figure is Yakushi Nyorai, the god of medicine who is flanked by the two bodhisattvas, Nikkō and Gakkō ("Sunlight" and "Moonlight" respectively).

|

Budō Yakushi (Grape Yakushi)

Daizenji Temple, Yamanashi Prefecture.

The temple claims the statue was

made in the Heian era.

Photo from this J-site.

|

|

Grape Yakushi, Budō Yakushi, 葡萄薬師

Daizenji Temple 大善寺 in Yamanashi prefecture possesses a one-of-a-kind seated image of Yakushi holding grapes in his left hand. Yamanashi is a grape-growing, winemaking region, and Budō Yakushi ブドウ薬師 (Grape Yakushi) is befittingly the protective deity of local grape farmers. Daizenji’s Yakushi Hall is a designated national treasure (dated to 1286). The temple claims its Budō Yakushi icon dates from the Heian era. For reasons unknown (to me), Yui Suzuki SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. does not mention this temple or this statue in her book, but she does make passing note (p. 42) of an intertwined grapevine motif on the mandorla of the ninth-century Yakushi statue at Shōjōji Temple (Fukushima) – a motif she says is also found on the eight-century pedestal of the famous bronze Yakushi statue at Yakushiji Temple in Nara. Writes Gabi Greve: “This is a special statue of Yakushi Nyorai, the Buddha of Medicine and Healing, in the wine-growing prefecture of Yamanashi (Japan), Katsunuma City 勝沼. During the Nara period, the famous Monk Gyoki 行基 visited the area and had a special dream about this deity one night. Yakushi was holding a bunch of grapes in his right hand, and in the other his usual medicine bottle. When he woke up, Gyoki started to carve the statue he had envisioned in his dream, and went on to found Daizen-ji Temple 大善寺 (designated a National Treasure), were the statue is still installed. It is the only statue of Yakushi holding grapes in Japan. In olden times, wine was one of the precious medicines of the day. Yakushi has since become the protector deity of the grape-growing farmers in this area. This is also the oldest part of Japan where real grapes, not wild mountain grapes, are grown. They make a drink called Budō Shu 葡萄酒, a bit different from wine, made like Japanese sake. But latest research shows that the grapes of this area originate in the Caucasus area and might have reached Japan via the Silk Road and Buddhism. Or maybe migragory birds dropped the seeds???” <end quote from Gabi Greve> Who is Japanese Monk Gyōki (Gyoki) 行基Gyōki (668-749) descended from Korean immigrants. He was the director of the Buddhist community at Tōdai-ji Temple (Nara), and was instrumental in raising funds for the construction of a giant effigy of Birushana, the so-called Great Buddha (Daibutsu) at Tōdaiji Temple. Legend contents that Emperor Shōmu himself helped carry buckets of dirt during the construction of the giant bronze image of Birushana, which was reportedly finished in +752.

|

Octopus Yakushi, Tako Yakushi たこ薬師

|

|

|

|

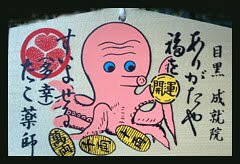

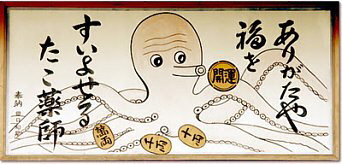

ABOVE PHOTOS: Votive tablets from Jōjū-in Temple 成就院 in Tokyo. These tables are inscribed with the term “Tako Yakushi” (多幸薬師 or たこ薬師), meaning “Yakushi of Great Fortune.” TA 多 means great, much, a lot. KO 幸 means fortune, luck, blessing. The word for octopus -- 蛸 -- is also pronounced TAKO, which gives rise to this pun and the appearance of an octopus surrounded by gold coins. One of the coins contains the characters KAIUN 開運, meaning "open to Luck, fortune and prosperity." There is a third word pronounced TAKO 胼胝 in Japan, meaning warts and calluses. Jōjū-in Temple also sells a rubbing-stone amulet known as Onade-ishi おなで石御守り. People rub it over their skin, body parts, and eyes to heal themselves of skin problems and other bodily ailments. <source Gabi Greve>

|

|

|

|

|

|

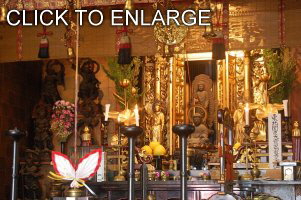

|

|

ABOVE PHOTOS (by Schumacher): Tako Yakushi たこ薬師 (Octopus Yakushi) at Tako Yakushidō (Octopus Yakushi Hall), Eifukuji Temple 永福寺 (lit. = Temple of Eternal Fortune), Kyoto City. Originally a Tendai sanctuary, Eifukuji is now part of the Pure Land Amida camp. The main icon of worship (not shown here) is a "hidden" stone statue of Yakushi, which temple authorities claim is over 800 years old. The two central wooden icons shown in this photo are omaedachi お前立 (stand-ins or substitutes for the real image). The standing image, says the temple, belonged originally to the mother of Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616) and itself was a "hidden" icon until about 25 years ago. A five-colored rope is tied around the effigy’s hand and extends to the center of the alter. Devotees can establish a karmic connection to the deity by clutching this rope. The origin and dating of the sitting image, says the temple, are unknown. The hidden stone icon is publicly displayed once every eight years. The next viewing will occur in October 2016. <source: Schumacher's talks with temple authorities). To the left and right of the central wooden icons are two attendants -- Nikkō and Gakkō, two Bosatsu who represent sunlight and moonlight respectively. At the far left and right are images of the twelve divine generals (Jūni Shinshō) who protect and serve Yakushi. The red-white winged object atop the altar is a zukō 塗香 (lit. = rubbing the body with incense or scent to worship Buddha).

Yui Suzuki SOURCE:

Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242. provides two charming stories about the origin of this temple in her book Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan (pp. 127-128). According to the temple's pamphlet, she writes: "Eifukuji was originally established in 1181 by a rich man who lived in the Muromachi district of Kyoto. This man had been a devoted worshiper of the Yakushi icon enshrined in Enryakuji's Central Hall (i.e., Saichō's Yakushi image). Every month, the pious man made a pilgrimage to Enryakuji to pay his respects to this icon. Eventually, knowing that he was becoming too old and weak to make this monthly journey, he prayed to the Yakushi icon to bestow upon him a replication of itself, which the man could bring back to worship in his own home. After making his wish, the devout man descended Mt. Hiei. That night, he dreamt of the Enryakuji Yakushi appearing before him, directing him to a certain place on Mt. Hiei where a stone Yakushi statue was secretly buried. The dream icon explained that this statue was carved by none other than Saichō himself. When the man dug in the place instructed by Yakushi the next day, he was overjoyed to discover a stone Yakushi icon that emitted a wondrous light. The man took the image home, built a ...six-by-four-bay worship hall for it, and named the temple Eifukuji.” She continues “......the second sacred narrative associated with Eifukuji' Yakushi image reveals the complex phenomena through wich this replicated icon was further transformed. This miracle tale relates that a Buddhist priest named Zenkō lived at Eifukuji during the Kenchō era (1249-1256). One day, Zenkō's mother fell gravely ill. She told her son that she might recover if she could eat some octopus. Being a Buddhist monk, Zenkō was not allowed to consume living things, but he decided to break his vows for the sake of his mother. Some of the townspeople witnessed Zenkō purchasing an octopus from a fisherman and reproached him. When Zenkō prayed to Yakushi for help, the octopus transformed itself into a set of eight sutra scrolls, which emitted a wondrous light in all directions. The townspeople who had criticized Zenkō all sang praises and pressed their hands together in prayer to the Buddha Yakushi. When they called upon Yakushi's name, the scrolls miraculously transformed back into the octopus, which jumped into the temple pond; the octopus then turned into Yakushi, who emitted an azure light the color of lapis lazuli. When this light struck Zenkō's mother, she was immediately healed of her illness. From then on, Eifukuji came to be known as the temple of the Octopus Yakushi. People came to worship the particular Yakushi icon at the temple in order to be healed from illness, to bear children, and to eliminate problems and difficulties of all kinds. This tale charmingly and humorously denotes Yakushi's role as a deity who bestows all kinds of worldly benefits on the pious. The origin of the associaton of this Yakushi icon with an octopus, however, is uncertain. According to the temple pamphlet, the name "Tako Yakushi" may have been derived from the fact that a pond (taku) was present on the original Eifukuji site. The phonetic sound of taku eventually may have been transmuted to tako, brighing forth the legend of an Octopus Yakushi. Regardless of their derivation, the two miracle stories from Eifukuji together demonstrate the centrality of Buddhist icon veneration for the Japanese, as well as the power of sacred narratives to animate such icons with life and authority just as effectively as ritual and scripture." <end Suzuki quote, pp. 127-128>

|

NIHON-JI DAIBUTSU

The Great Buddha (Daibutsu 大仏) stone carving at Nihonji Temple 日本寺 in Chiba Prefecture is a representation of Yakushi Rurikō 薬師瑠璃光 (aka Yakushi, the Medicine Buddha, the Buddha of Healing). This stone-cliff Buddha (magaibutsu) is 31.05 meters in height. It, along with 1,500 smaller statues in the area, were carved by master artisan Jingoro Eirei Ono 大野甚五郎英令 and his 27 apprentices in the 1780s and 1790s. This giant statue is twice the size of the Kamakura Daibutsu and Nara Daibutsu, making it the largest of pre-modern Japan’s extant Big Buddha statues. The Nihon-ji Temple itself dates back to 725 AD. At the same location, one can find carvings of 500 Rakan (Arhat), as well as a gigantic 30-meter-high stone carving of the Kannon Bosatsu. The Rakan images took 20 years to carve. All of these carvings are located at Mt. Nokogiri-yama 鋸山. The literal meaning of this mountain’s name is “saw-tooth mountain,” for its shape looks like the teeth of a saw. See Nihonji Temple’s web site for more details.

Click any image above to see a larger photo.

(L to R) First Three Photos of Yakushi by Goto Osami; Last Photo of Kannon by Mark Schumacher

|

|

|

|

|

Yakushi Nyorai

Stone, Kamakura Era, housed at the Kokuhōkan Museum 国宝館

(located inside Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine), Kamakura

|

Yakushi Nyorai

Wood, Kamakura Era

Housed at Kokuhōkan Museum, Kamakura. Treasure of Gokurakuji Temple 極楽寺, Kamakura

|

Yakushi Nyorai - Wood, Kamakura Era

Housed at the Kokuhōkan Museum inside

Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine (Kamakura)

|

|

LEARN MORE LEARN MORE

- Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan. By Yui Suzuki. Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 192 pages, including an appendix, list of characters, endnotes, bibliography and index. 60 illustrations, mostly in color. Suzuki's book deserves a prominent place on the bookshelves of scholars and art historians of Japan's early religious experience. For a review of the book by Mark Schumacher, see Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 34, 2013, pp. 234-242.

- 12 Vows of Yakushi Nyorai (this site).

- JAANUS entry on Yakushi Nyora / Buddha.

- JAANUS entry on Yakushi Keka Ceremony.

- Nara National Museum entry on Yakushi Keka Ceremony.

- Soothill & Lewis Hodous. A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms. With Sanskrit & English Equivalents. Plus Sanskrit-Pali Index. By William Edward Soothill & Lewis Hodous. Hardcover, 530 pages. Published by Munshirm Manoharlal. Reprinted March 31, 2005. ISBN 8121511453.

- Digital Dictionary of Chinese Buddhism (login as "guest")

- Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙, the "Collected Illustrations of Buddhist Images." Published in 1690 (Genroku 元禄 3). Modern-day reprints are available for online purchase here.

- Hall of Medicine Buddha at Toji Temple - Kyoto

Numerous Photos of Yakushi from Healing-Touch.

- Yakushiji Temple in Nara (J-site; Lots of Photos).

- Yakushiji Temple Flash Presentation (J-site).

- Three Views of Yakushi - Nara National Museum (J-site).

- The Big Book of Reiki Symbols: The Spiritual Transition of Symbols and Mantras of the Usui System of Natural Healing. By Mark Hosak, Walter Luebeck, Christine M. Grimm. Lotus Press 2007. Includes section about Yakushi Buddha.

- Running the Shikoku Pilgrimage: 900 Miles to Enlightenment. Book by Amy Chavez.

- Echoes of Incense. Story by Don Weiss about 88-temple pilgrimage in Shikoku.

- Butsuzou.com. Modern Yakushi statues available for online purchase.

- List of Japan's National Treasures (J-site).

- Sanskrit Seed Images and Shingon Mantras (Tobifudo). Above seed syllables and mantras used with permission from Ryūkozan Shōbō-in Temple 龍光山正寶院. Based in Tokyo. Tendai Sect.

- Handbook on Viewing Buddhist Statues, by Ishii Ayako. Japanese language only. Some images shown above were scanned from this book; 192 pages; 80+ color photos; ISBN-10: 4262156958.

- Chinese video of the Yakushi Sutra at this C-site.

Buddhist-Artwork.com

Statues of Yakushi Nyorai are available

for online purchase at our sister site.

|

|