|

|

|

|

MAKING BUDDHIST STATUES

MATERIALS & TECHNIQUES

Glossary with 60+ Terms

|

SELECT CATEGORY

How are Buddha Statues Created? This page provides an overview of the primary materials and techniques used by Japanese artisans to create Buddhist statuary. It also provides the Japanese spellings and pronunciations for the most widely used materials and methods. This glossary is not comprehensive. More terms will be added over time.

Butsuzō 仏像

Butsuzō. Literally Buddha Statue. Also spellled Butsuzo or Butsuzou. A Japanese term that refers to all types of Buddhist statuary regardless of the material used or the ranking of the deity (e.g., Buddha, Bodhisattva, Deva, Monk).

Who Made Japan’s Buddha Statues? Who Made Japan’s Buddha Statues?

Please visit the Busshi Index for an overview of Japan’s main sculptors (Busshi) and sculpting styles, plus a helpful A-to-Z index covering 100+ sculptors. Busshi 仏師 literally means "Buddhist Teacher."

Sources. This page relies heavily on various Japanese-language resources, but most especially, it relies on the wonderful English-language database of the Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System. Links to JAANUS are provided for most of the entries presented below. You are strongly encouraged to explore JAANUS.

|

WOOD

Ichiboku Zukuri Single Block

Mokuchō Wood Sculpture

Mokushin Kanshitsu Wood Core

Natabori Hachet Carving

Timber (Wood) List

Uchiguri Hollowing Out

Warihagi Split and Join

Wood Names Timber List

Yosegi Zukuri Joined Block

METAL

Chuzo, Chūzō Casting

Chukin, Chūkin Metal Casting

Ginpaku Silver Foil / Leaf

Haku Foil / Leaf

Hakuoshi Applied Metal Foil

Imono Casting Method

Kigata Imono Casting Method

Kinpaku Gold Foil / Leaf

Kinpakuoshi Applied Gold Leaf

Kirihaku Metal Patterns

Kirikane Decorative Method

Kondo, Kondō Gilt Bronze

Oshidashibutsu Repousse

Rogata, Rōgata Lost Wax

Shippaku Foil & Lacquer

Tokin Gold Gilding Method

CLAY

Saishikizo Painted statue

Senbutsu Unglazed Clay Tiles

Sozo, Sozō Clay statues

DRY LACQUER

Dakkatsu Kanshitsu Hollow Dry

Haku Foil or Leaf

Kanshitsu Dry Lacquer Method

Kokuso Urushi Lacquer Paste

Mokushin Kanshitsu Wood Core

Shingi Wood Frame

Shippaku Foil & Lacquer

STONE

Ganzo, Ganzō Niche Carving

Magaibutsu Cliff / Cave Buddha

Sekibutsu Stone Buddha

Sekizo, Sekizō Stone Carving

Stones - Other Entries

|

|

WOOD 木造 (Mokuzō, Mokuzou, Mokuzo) WOOD 木造 (Mokuzō, Mokuzou, Mokuzo)

Main Techniques & Materials for Making Wood Statues

See JAANUS for wonderful review of wood sculpture.

Wood wasn’t always the primary material used to create Buddhist sculpture in Japan. In the Asuka and Nara eras, gilt bronze ruled the roost, with wood competing as well with clay and dry-lacquer statuary. From the Heian period onward, however, wooden sculpture gains ascendency, and thereafter dominates the world of Japanese Buddhist sculpture. Although sandalwood is the most prized of all the woods, it is not indigenous to Japan or China, and substitutes had to be found. In the +7th century, the broadleaf camphor 樟 tree was the main material used for wooden sculpture in Japan. In subsequent centuries, however, the Japanese turned increasingly to cypress (hinoki 桧), nutmeg (kaya 榧), the Judas tree (katsura 桂), and other timbers readily available in Japan. The popularization of wooden Buddhist statuary in Japan was no doubt accelerated by Japan’s ancient practice of tree worship, for wood has long been revered as a vehicle housing the gods and spirits of Japan’s indigenous Shinto faith. Wood sculpture reaches its appex (in my mind) in the Kamakura period, and thereafter falls into decline, surpassed beyond repair by secular (non-religious) folk art in the Edo Era.

|

Guze Kannon 救世観音

Height = 178.8 cm

Houryuuji (Horyuji)

法隆寺 (Nara)

7th Century, Wood = Camphor 樟

Made from single block of wood. |

|

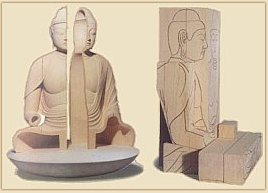

Ichiboku Zukuri 一木造. Single-Block Carving. Technique used in the early centuries, rising to prominence in the Nara and early Heian periods, but later supplanted by the yosegi-zukuri (joined block) technique. Statues are carved from one solid block of wood in a four-step process (see clipart below). Although the pedestal, halo, and legs (for sitting statues) might be carved from a secondary block of wood, all ichiboku-zukuri statues share one common characteristic -- the head and torso are carved from the same single block. The earliest extant wooden statue in Japan (first half 7th century) is the Guze Kannon 救世観音 at Houryuuji Temple 法隆寺 in Nara. It was carved from one piece of camphor 樟 wood using the ichiboku-zukuri technique. Ichiboku Zukuri 一木造. Single-Block Carving. Technique used in the early centuries, rising to prominence in the Nara and early Heian periods, but later supplanted by the yosegi-zukuri (joined block) technique. Statues are carved from one solid block of wood in a four-step process (see clipart below). Although the pedestal, halo, and legs (for sitting statues) might be carved from a secondary block of wood, all ichiboku-zukuri statues share one common characteristic -- the head and torso are carved from the same single block. The earliest extant wooden statue in Japan (first half 7th century) is the Guze Kannon 救世観音 at Houryuuji Temple 法隆寺 in Nara. It was carved from one piece of camphor 樟 wood using the ichiboku-zukuri technique.

Although the preferred method of sculpture until the 11th century, the single-block technique suffered from three major limitations. First, life-size or larger statues were enormously heavy and therefore hard to move from place to place. Second, a wood core often develops large cracks that spread through the statue as the timber dries. Third, the problems of weight and cracking could be overcome to some degree by hollowing out the statue’s interior, but the statue’s size was still severely curtailed by the size of the tree truck from which it is carved. The split-and-join method (warihagi) and the joined-block technique (yosegi-zukuri) that emeged in the late 10th century provided solutions to these limitations, and thereafter the popularity of single-block carving falls into decline. Single-block carving experienced a revival in the Edo Period when two wandering artists revived the method. They were the Buddhist priest Enkū 円空 (1632-1695) and the Zen priest Mokujiki Myōman 木食明満 (1718-1810). Nearly all of their extant pieces were carved from a single block of wood, including the pedestals, and were not hollowed out. This gives their pieces a compelling freshness compared to the traditional refined works of Buddhist sculpture. Neither was widely recognized during his lifetime, but each has since achieved great fame. For more details on single-block carving, see JAANUS.

|

Ichiboku Zukuri 一木造 = Single Block Carvings

|

|

1

Block Cutting

Kidori 木取

Prepare piece of wood with right size for intended statue

|

2

Rough Cut

Arabori 荒彫

with round chisel or other cutting instrument

|

3

Fine Cut

Kozukuri 小造り

Detailed carving and smoothing of surface

|

4

Finishing

Shiage 仕上げ

Refined cutting

for final piece

|

|

Above Clipart = Adapted from stock image used by most Japanese museums

|

|

Single-block carvings are also known as natabori 鉈彫 (literally “hatchet carving”), but natabori pieces are differentiated from ichiboku zukuri carvings by the characteristic round chisel (nata 鉈) markings left on the statue’s surface.

Mokuchou, Mokuchō, Mokucho 木彫. Literally “Wooden Sculpture.”

Mokushin Kanshitsu 木心乾漆. Wood-core dry lacquer statues. The statue’s shape is roughly carved in wood, and then molded over by lacquer mixed with sawdust or other fibrous material (kokuso urushi 木屎漆). See more details below.

Natabori 鉈彫 = Hachet carvings. Popular from last half of the 10th century to around the 12th century; revived again in Edo period. Single-block carvings (ichiboku zukuri) are sometimes called natabori, but natabori statues are differentiated from ichiboku-zukuri carvings by the characteristic round chisel (nata 鉈) markings that are added to the statue’s surface. Natabori images are rough-cut (arabori 荒彫) or fine-cut (kozukuri 小造り) without undergoing the finishing (shiage 仕上げ) process, and for this reason, some Japanese claim that natabori are unfinished works, while others claim that natabori statues are a unique sculptural style. In the Edo Period, two wandering artists of great fame revived this technique. They were the Buddhist priest Enkū 円空 (1632-1695) and the Zen priest Mokujiki Myōman 木食明満 (1718-1810). Nearly all of their extant pieces were carved from a single block of wood, including the pedestals, and were not hollowed out. This gives their pieces a freshness that is completely different from the refined works of traditional Buddhist sculpture. Nearly all of Enkū’s pieces (allegedly 120,000 figures) were carved as single-block figures, including the pedestals, and were not hollowed out. Enkū was not widely recognized during his lifetime, but has achieved great fame in modern-day Japan. He hailed from Mino 美濃 (modern Gifu prefecture). He was not affiliated with any temple or workshop, nor considered a professional maker of Buddhist images. Rather, he was a mountain ascetic and pilgrim who traveled about the eastern and northern parts of Japan carving statues in exchange for food and shelter. For more on natabori, see JAANUS. Natabori 鉈彫 = Hachet carvings. Popular from last half of the 10th century to around the 12th century; revived again in Edo period. Single-block carvings (ichiboku zukuri) are sometimes called natabori, but natabori statues are differentiated from ichiboku-zukuri carvings by the characteristic round chisel (nata 鉈) markings that are added to the statue’s surface. Natabori images are rough-cut (arabori 荒彫) or fine-cut (kozukuri 小造り) without undergoing the finishing (shiage 仕上げ) process, and for this reason, some Japanese claim that natabori are unfinished works, while others claim that natabori statues are a unique sculptural style. In the Edo Period, two wandering artists of great fame revived this technique. They were the Buddhist priest Enkū 円空 (1632-1695) and the Zen priest Mokujiki Myōman 木食明満 (1718-1810). Nearly all of their extant pieces were carved from a single block of wood, including the pedestals, and were not hollowed out. This gives their pieces a freshness that is completely different from the refined works of traditional Buddhist sculpture. Nearly all of Enkū’s pieces (allegedly 120,000 figures) were carved as single-block figures, including the pedestals, and were not hollowed out. Enkū was not widely recognized during his lifetime, but has achieved great fame in modern-day Japan. He hailed from Mino 美濃 (modern Gifu prefecture). He was not affiliated with any temple or workshop, nor considered a professional maker of Buddhist images. Rather, he was a mountain ascetic and pilgrim who traveled about the eastern and northern parts of Japan carving statues in exchange for food and shelter. For more on natabori, see JAANUS.

Uchiguri 内刳. The hollowing out of statues. Extremely important innovation in wood sculpture that emerged during the 9th century. This technique made the statue lighter and helped prevent the wood from cracking as it dried. See JAANUS for details.

Warihagi 割矧. Split-and-Join Technique. A major carving method introduced in the later half of the 10th century, almost at the same time as the yoseki zukuri (joined-block assembly) technique. One-block statues are split, sometimes into several pieces, hollowed out, and rejoined. Typically the head and torso are carved from one block. The block is then split along the grain to enable hollowing out, after which the pieces are rejoined. The head was sometimes removed from the torso as well and later reattached (a practice also used in the yoseki zukuri method). The technique allowed for greater hollowing-out of the wood, which in turn led to the widespread acceptance of the yoseki-zukuri process. Warihagi was suitable for making smaller-than-life-size statues, while yoseki-zukuri was used primarily for life-size or larger statues. The method was likely developed to enable maximum weight reduction while retaining as much as possible of the original single-block method of wood sculpture. See JAANUS for more details.

Yosegi Zukuri 寄木造. Joined-Block Technique, Assembled-Wood Method. Also read Yoseki Zukuri. Statues are made from several pieces of timber and then joined together. A major carving technique introduced in the later half of the 10th century. Up until then, statues were carved from a solid block of wood using a technique called ichiboku-zukuri 一本造. The new yosegi-zukuri technique reached its apogee with Unkei (1148 - 1223 AD), one of Japan’s most highly acclaimed sculptors. Instead of using one solid piece of wood, the statue is carved in a piecemeal fashion from partially hollow blocks of wood. First, the individual body parts are carved roughly and separately. Second, the pieces are assembled, and only then, thirdly, does detailed carving begin. This new method had various advantages. Not only was it faster, allowing several artists to work in tandem on different parts, but also the final sculpture was much lighter than one carved from a single block of wood. The assembled-wood technique also satisfied conditions for systematized mass-production (i.e., the ability to produce large quantities of statues with standard specifications). By the late Heian era, large-scale projects involving dozens, even hundreds, of statues were commissioned. Moreover, the technique allowed Japan’s artisans to create ever-larger statues of the Buddhist divinities. Finally, in the centuries that followed, the prefabricated nature of the individual body parts allowed temples to quickly repair or replace damaged or destroyed body parts -- e.g., placing the undamaged head of an older statue (whose body was ruined by fire or earthquake) onto another statue whose body was still in good repair. Yosegi Zukuri 寄木造. Joined-Block Technique, Assembled-Wood Method. Also read Yoseki Zukuri. Statues are made from several pieces of timber and then joined together. A major carving technique introduced in the later half of the 10th century. Up until then, statues were carved from a solid block of wood using a technique called ichiboku-zukuri 一本造. The new yosegi-zukuri technique reached its apogee with Unkei (1148 - 1223 AD), one of Japan’s most highly acclaimed sculptors. Instead of using one solid piece of wood, the statue is carved in a piecemeal fashion from partially hollow blocks of wood. First, the individual body parts are carved roughly and separately. Second, the pieces are assembled, and only then, thirdly, does detailed carving begin. This new method had various advantages. Not only was it faster, allowing several artists to work in tandem on different parts, but also the final sculpture was much lighter than one carved from a single block of wood. The assembled-wood technique also satisfied conditions for systematized mass-production (i.e., the ability to produce large quantities of statues with standard specifications). By the late Heian era, large-scale projects involving dozens, even hundreds, of statues were commissioned. Moreover, the technique allowed Japan’s artisans to create ever-larger statues of the Buddhist divinities. Finally, in the centuries that followed, the prefabricated nature of the individual body parts allowed temples to quickly repair or replace damaged or destroyed body parts -- e.g., placing the undamaged head of an older statue (whose body was ruined by fire or earthquake) onto another statue whose body was still in good repair.

According to various Japanese sources, the yosegi-zukuri method was introduced due primarily to the lack of large trees and a growing creative impulse to construct gigantic statues of the Buddha (Nyorai) and Bodhisattva (Bosatsu). Others say the technique stems from Jouchou (Jocho, Jōchō) 定朝, the great Buddhist sculptor (died 1057AD) who is credited with the outstanding Bosatsu on Clouds and Amida statues at Byoudouin Temple (Byōdō-in, Byodoin) 平等院 in Kyoto. This large-scale extant installation of 50-plus Buddhist statues, completed in 1053 AD, provides many examples of both the split-and-join technique and assembled-wood method. These construction methods allowed Jouchou and his team to plan the entire production process before work even began. Indeed, Jouchou is credited with perfecting both techniques. Despite China’s strong influence on Japan’s sculpting traditions during most of this period, the craftsmanship of Jouchou and his team is considered a prime example of Japan’s flowering indigenous artistic genius. Nonetheless, after the 10th century, Japanese Buddhist sculpture became somewhat standardized owing to the convenience of these new systematized mass-production techniques. After Jouchou’s death, many statues were made with similar postures and expressions. Modern Japanese art historians lament the lack of individuality in sculptuary of subsequent decades. In the Kamakura era, however, a new artistic master, Unkei 運慶 (1148 - 1223 AD), arrives on the scene. One of Japan’s most highly acclaimed sculptors, Unkei sparks a resurgence in Japanese Buddhist statuary and artistic energy. According to various Japanese sources, the yosegi-zukuri method was introduced due primarily to the lack of large trees and a growing creative impulse to construct gigantic statues of the Buddha (Nyorai) and Bodhisattva (Bosatsu). Others say the technique stems from Jouchou (Jocho, Jōchō) 定朝, the great Buddhist sculptor (died 1057AD) who is credited with the outstanding Bosatsu on Clouds and Amida statues at Byoudouin Temple (Byōdō-in, Byodoin) 平等院 in Kyoto. This large-scale extant installation of 50-plus Buddhist statues, completed in 1053 AD, provides many examples of both the split-and-join technique and assembled-wood method. These construction methods allowed Jouchou and his team to plan the entire production process before work even began. Indeed, Jouchou is credited with perfecting both techniques. Despite China’s strong influence on Japan’s sculpting traditions during most of this period, the craftsmanship of Jouchou and his team is considered a prime example of Japan’s flowering indigenous artistic genius. Nonetheless, after the 10th century, Japanese Buddhist sculpture became somewhat standardized owing to the convenience of these new systematized mass-production techniques. After Jouchou’s death, many statues were made with similar postures and expressions. Modern Japanese art historians lament the lack of individuality in sculptuary of subsequent decades. In the Kamakura era, however, a new artistic master, Unkei 運慶 (1148 - 1223 AD), arrives on the scene. One of Japan’s most highly acclaimed sculptors, Unkei sparks a resurgence in Japanese Buddhist statuary and artistic energy. |

|

|

WOOD (TIMBER) LIST

Most Common Wood Used to Make Buddha Statues

|

|

WOOD

|

DESCRIPTION

|

|

沈香

|

Jinkō, Jinkou, Jinko = Agarwood, Agar

|

|

栢木

ばいむ

|

Baimu = Sandalwood Substitutes. Baimu is the Chinese reading. Hakuboku is the Japanese reading. Sandalwood is a fine-grained aromatic wood and the most prized of all timber for Buddhist statuary. It is not indigenous to East Asia. China and Japan had to import it from India. By China’s Tang dynasty, however, the idea that a wood called BAIMU (type of cypress) could be used as a substitute was presented by the Chinese Priest Hui Zhao. His writings and other documents from those times provided justification for using woods other than sandalwood.

|

|

白檀

|

Byakudan = Sandalwood (literally “white sandalwood”). An aromatic wood, the most prized and most expensive for making Buddhist statuary. Reportedly the first-ever Buddha statues from India were made using sandalwood. The sandalwood tree is not indigenous to Japan or China (or at least very scarce). Substitute woods were thus used instead. The trunk of the sandalwood tree is small, making it unsuitable for large statues. There are various types of Sandalwood.

- 檀木 Sandalwood, Generic Term (Danboku だんぼく)

- 白檀 White Sandalwood (Byakudan びゃくだん)

- 緑檀 Green Sandalwood (Ryokudan りょくだん)

- 紫檀 Red Sandalwood, Kingwood (Shitan したん)

- 紅檀 Crimson, Deep Red (Kutan くたん, Kōdan こうだん)

- 黒檀 Black Sandalwood or Ebony (Kokutan こくたん)

|

|

檀像

檀像様

彫刻

|

Danzō, Danzou, Danzo. A Buddhist statue made from aromatic wood, such as sandalwood (byakudan 白檀), rosewood (shitan 紫檀), ebony (kokutan 黒檀), Japanese bead tree (sendan 栴檀), or Japanese nutmeg (kaya 榧). Usually very small in size and carved with fine details. The first danzo brought from China to Japan is reportedly a small Kannon 観音 statue enshrined in +595 at Hisodera Temple 比蘇寺 in Yoshino 吉野 (Nara). When substitute woods are used instead of sandalwood, the statues may also be called Danzōyō Chōkoku 檀像様彫刻 (lit. danzō-style statues). For more, see JAANUS.

|

|

栢木

はくぼく

|

Hakuboku = Sandalwood Substitutes. The Japanese reading of the term BAIMU. Refers generally to all woods that can substitute for sandalwood, but also used as a term referring only to aromatic woods like kaya (榧 = Japanese Nutmeg). Kaya became a popular substitute for sandalwood in the Nara period and early Heian era.

|

|

霹靂木

|

Hekireki = Type of Cypress

雷が落ち神や霊の宿った樹木のこと・これは楠木

|

|

桧

檜

|

Hinoki = Japanese Cypress. Very light weight.

Used commonly today for inexpensive small reproductions.

|

|

桂

|

Katsura = Judas Tree. Used often in Nara and Heian eras.

|

|

榧

|

Kaya = Japanese Nutmeg. Needleleaf tree.

Aromatic wood highly prized as substitue for sandalwood.

|

|

欅

|

Keyaki = Zelkova. Type of gray-black elm tree.

Hardwood. Also used to construct tansu (chests).

|

|

桐

|

Kiri = Paulownia. Used for making boxes & chests (tansu)

|

|

黒檀

|

Kokutan = Ebony, also known as Black Sandalwood.

|

|

香木

|

Kōboku = Generic term for aromatic scented wood

|

|

樟

|

Kusu = Camphor.

Main wood used for statues in Japan’s Asuka Period.

|

|

楠木

|

Kusunoki = Japanese Cinnamon

Highly prized aromatic wood.

|

|

桜

|

Sakura = Japanese Cherry Tree

|

|

栴檀

|

Sendan = Japanese Bead Tree (Melia Azedarach).

Also an alternative term for Sandalwood (byakudan 白檀).

|

|

白木

|

Shiraki = White Fir. Very light weight.

Cheapest wood for small modern reproductions.

|

|

紫檀

|

Shitan = Rosewood.

Also known as Red Sandalwood or Kingwood

|

|

柘植

|

Tsuge = Boxwood. Type of wild mulberry. Hardwood.

Used commonly today for small wooden reproductions.

|

|

METAL CASTING 鋳金 (Chūkin, Chuukin, Chukin)

Bronze was the most-used metal for casting, although statues were also cast from other copper alloys, and from silver, gold, and other metals. Most metals were imported into Japan prior to the +7th century. But in +708, copper was discovered in great quantity in Japan. Bronze remained the most dominant form of statuary until the Heian era, when it was finally supplanted by wood. The lost-wax technique (rougata 蝋型) was the most popular method for casting metal statues, and was utilized widely until the 12th century. Most of Japan’s extant bronze statues are gilded.

|

|

Chuuzou, Chūzō, Chuzo 鋳造. Also known as Imono 鋳物. Method of casting. The base material (metal, plaster, clay, or glass) is heated, melted to liquid, and then poured into a mold (igata 鋳型). The mold (mould) is removed after the material has hardened, revealing the solid form within. The term Chuuzoubutsu 鋳造仏 (also spelled Chūzōbutsu, Chuzobutsu) refers specifically to cast Buddhist images. Chuuzou, Chūzō, Chuzo 鋳造. Also known as Imono 鋳物. Method of casting. The base material (metal, plaster, clay, or glass) is heated, melted to liquid, and then poured into a mold (igata 鋳型). The mold (mould) is removed after the material has hardened, revealing the solid form within. The term Chuuzoubutsu 鋳造仏 (also spelled Chūzōbutsu, Chuzobutsu) refers specifically to cast Buddhist images.

Chuukin, Chūkin, Chukin 鋳金. Metal casting. Often used interchangeably with the term Chuuzo or Imono (see prior entry). Chuukin refers specifically to metal, whereas Chuuzo and Imono refer to a casting method that includes other materials like clay and glass. See JAANUS Chuukin for details.

Ginpaku 銀箔. Silver foil or silver leaf.

Haku 箔. Literally “foil” or “leaf.” A general term referring to various techniques for adding metal decorations to Buddhist statues made of wood, dry lacquer, or clay. Various materials were used, including gold, silver, copper, tin and brass, but the most common were gold (kinpaku 金箔) and silver (ginpaku 銀箔). The oldest extant haku artwork in Japan dates from the late 7th century. It is found on the wall paintings of the Takamatsuzuka 高松塚 tomb in Asuka (near Nara). Visit this outside site for photos. One important technique for affixing gold foil to an object (with lacquer or glue) is known as kinpakuoshi 金箔押. Another major technique is called shippaku 漆箔, in which gold or silver foil is affixed to lacquer and then applied to statues made of wood or dry-lacquer (kanshitsu 乾漆). Another widely used technique was kirikane 切金, which involved cutting foil into small pieces to make intricate designs on statue garments. See JAANUS Haku for details.

Hakuoshi 箔押. Applying metal foil, usually gold, to an object.

Imono 鋳物. Method of casting. See Chuuzou above.

Kigata Imono 木型鋳物. Casting utilizing a clay mold formed directly over a wood model (kigata 木型). Became common during the Kamakura period. See JAANUS Kigataimono for details.

Kinpaku 金箔. Gold foil or gold leaf.

Kinpakuoshi 金箔押. Technique for affixing gold foil to an object using lacquer or glue.

Kirihaku 切箔. Decorative metal pattern on sculptures or paintings. See JAANUS Kirihaku for details

|

Kirikane 截金

Decorative Technique

Seiryouji Shaka

987 AD, Wood

Height = 162.67 cm

Yosegi Zukuri 寄木造

(Assembled Wood)

Seiryouji Temple 清凉寺

|

|

Kirikane 切金. Also written 截金. Sometimes pronounced Kirigane. Literally "cut gold." A decorative technique used in Buddhist artwork to adorn Buddhist statues. The technique came from Tang China, arriving in Japan sometime in the 7th century. Leaves/sheets (haku 箔) of gold or silver (sometimes other metals) are pressed together, cut into long thin strips or other shapes, then affixed to the surface of a statue or painting. A related term is kirihaku 切箔, which refers to a decorative metal pattern on sculptures or paintings. Kirikane was a popular technique in the Heian period for sculpture and painting. But it fell into decline during the Kamakura period, replaced by the use of gold paint (kindei 金泥) for creating the decorative gold outlines and patterns. Kirikane also refers to a decorative method popular in the Kamakura period for adorning lacquer statues with cut metal. Please see JAANUS Kirikane for details. For examples of this technique, see Nakamura Keiboku.

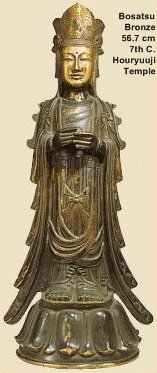

Kondou, Kondō, Kondo 金銅. Gilt bronze. Related terms include 金銅造 (gilt-bronze technique), kondouzou 金銅像 (gilt-bronze statue), and kondoubutsu 金銅仏 (gilt-bronze Buddha). Gilding is a method wherein objects made of bronze or copper are coated with a thin layer of gold (tokin 鍍金) or gold leaf (hakuoshi 箔押). In Japan, the Asuka and Nara periods are considered to be the “Great Age of Gilt Bronze Buddhist Sculpture.” It is not until the Heian period that wooden sculpture surpasses gilt bronze in popularity. Nonetheless, gilt bronze statues flourish in Japan until at least the 12th century, and were made primarily using a method called rougata 蝋型 (lost-wax technique). The first Buddhist image to enter Japan came from Korea during the reign of Emperor Kinmei 欽明 (539-571 AD). It was a gilt-bronze statue. See Early Japanese Buddhism for details. The earliest gilding techniques are credited to the Chinese. See JAANUS Kondou for details.

Oshidashibutsu 押出仏. A repousse relief depicting Buddhist deities. Also spelled tsuichoubutsu 鎚ちょう仏. Usually tiny and made of bronze. The relief is produced by hammering a thin bronze sheet placed over a metal matrix. Probably introduced from China sometime around the 7th century. The technique was suitable for producing numerous Buddhist icons. The oldest extant piece, located at Houryuuji Temple 法隆寺 (Nara), is from the mid-7th century. It depicts the Myriad Buddha (sentaibutsu 千体仏) in three bronze plates on the interior walls of the Tamamushi Shrine (Tamamushi no zushi 玉虫厨子) kept at the temple. Other famous oshidashibutsu pieces are also preserved at the temple. See JAANUS Oshidashibutsu for details.

Rougata, Rōgata, Rogata 蝋型. Lost-Wax Metal Casting. Also known as Rougata Chuuzou 蝋型鋳造 or Rougata Imono 蝋型鋳物. A popular technique for metal casting that was used in the 6th century and continued into Japan’s Edo period. A model of the statue is made in clay (or other flexible material). It is then covered in beeswax, molded to the required shape, and engraved with fine surface details. The wax is then covered by an outer layer of soft clay or plaster. This was then fired, hardening the clay and causing the wax to melt and flow out of the mold. The gap left by the wax is then filled with melted metal. Once hardened, the inner and outer molds are removed. There are different variations of this technique, one in which the inner clay core is not used. The bulk of Japan’s earliest surviving bronze statues were made using such techniques. See JAANUS Rougata for details.

Shippaku 漆箔. Technique in which gold or silver foil is affixed to lacquer and then applied to statues made of wood, dry-lacquer, and occasionally on stone statues, clay figures, and metal statuary. Found most commonly on Buddhist statues made of wood and dry lacquer. Statues made using the shippaku method are called shippakuzou 漆箔像. See JAANUS Shippaku for details.

Tokin 鍍金. A decorative gilding technique in which objects are coated with a thin layer of gold. Used commonly for Buddhist statues during the 7th and 8th centuries, and revived once again in the Kamakura period. See JAANUS Tokin for details.

|

|

CLAY 塑造 (Sozō, Sozou, Sozo)

Clay sculpture flourished in the +8th century, but was thereafter supplanted by the popularity of wood. Its failure to become a long-term popular material for statuary reflects perhaps the fragile nature of clay.

|

|

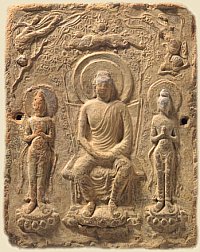

Sanzon Senbutsu

Buddha Triad (Senbutsu)

Late 7th Century

H 24.5 cm W 19.6, D 3.7 cm

Courtesy: Miho Museum

|

Saishikizō, Saishikizou, Saishikizo 彩色像. Painted statue. Most saishikizou are clay images or wooden images. The term refers specifically to images entirely colored, and is not used for statues with only a few painted features. See JAANUS Saishikizou for details. Saishikizō, Saishikizou, Saishikizo 彩色像. Painted statue. Most saishikizou are clay images or wooden images. The term refers specifically to images entirely colored, and is not used for statues with only a few painted features. See JAANUS Saishikizou for details.

Senbutsu 甎仏. Buddhist figures shown in relief on unglazed clay tiles, either dried naturally or fired. Also written 磚仏. Introduced to Japan from China in the second half of the 7th century. The Japanese term SEN 專 means unglazed clay tile. Clay is typically pressed into a mold, then dried or fired. Sometimes gold leaf (kinpaku) is applied to the clay surface. The mold allowed for mass-production of the image, and many images were thus made in large numbers, often to adorn temple walls (sentaibutsu 千体仏). If a mold broke, a new one was made from an existing figure, but once fired, the new mold was about 20% smaller than the original. Hence, products from the new mold were smaller than the original mold. This method of reproducing molds, with each generation gettting smaller and smaller, is called fumigaeshi (踏返し). See JAANUS Senbutsu for details. Also see Dr. Gabi Greve’s page.

|

Shitsukongou-shin

執金剛神 (Closeup)

Photo by Ogawa Kouzou

|

Sozō, Sozou, Sozo 塑造 or 塑像. Clay statue. Also spelled sozou 塑像, shouzou 摂像, deizou 泥像, ten 捻, and shou 摂. Two main techniques involving clay were used in Japan. Both came to Japan from China in the late Asuka period, and gained popularity during the Nara era. Clay, because it allowed for detailed modeling, was very suitable for the realistic sculptural style of the Nara period, but its popularity soon fizzled out. Influences from China’s Sung Dynasty during Japan’s Kamakura period brought about a semi-revival in clay statuary in Japan, but the styles and techniques differed from those in the Nara period. See JAANUS Sozou for details. Sozō, Sozou, Sozo 塑造 or 塑像. Clay statue. Also spelled sozou 塑像, shouzou 摂像, deizou 泥像, ten 捻, and shou 摂. Two main techniques involving clay were used in Japan. Both came to Japan from China in the late Asuka period, and gained popularity during the Nara era. Clay, because it allowed for detailed modeling, was very suitable for the realistic sculptural style of the Nara period, but its popularity soon fizzled out. Influences from China’s Sung Dynasty during Japan’s Kamakura period brought about a semi-revival in clay statuary in Japan, but the styles and techniques differed from those in the Nara period. See JAANUS Sozou for details.

PHOTO AT RIGHT

Nara Era, H = 173.9

Clay 塑像 with Paint 彩色

Tōdaiji Temple 東大寺

Domon 土紋. Less commonly written 土文. Decorative drapery made from clay. This method of ornamentation appeared in the late 13th century and is unique to the Kamakura area. It featured exceptionally deep drapery folds made with clay molds, or clay decorative elements in the shape of crests, flowers, and leaves. The finished clay relief was then affixed to the statue, often using lacquer.

|

|

|

DRY LACQUER 乾漆 (Kanshitsu)

Dry-lacquer statues flourished in the +8th century. Such statues generally surpassed wood in popularity during that century, but thereafter dry lacquer was overshadowed by the popularity of wood. Two techniques in particular were used. The “hollow dry lacquer” method and the “wood-core dry lacquer” method. Both methods allowed the construction of extremely large yet lightweight statues that could be moved easily from temple building to building, or among temples. Lacquer itself dries to the hardness of stone. Hundreds of dry-lacquer statues from the Nara era are still extant, including those as Toudaiji Temple 東大寺, Koufukuji Temple 興福寺, Toushoudaiji Temple 唐招提寺, Houryuuji Temple 法隆寺, and Fujiidera Temple 藤井寺 (also spelled 葛井寺). Many are painted or gilt finished.

|

|

Ashura 阿修羅

Hollow Dry Lacquer

H = 153 cm, Nara Era

One of the

Eight Guardians

(Hachi Bushuu 八部衆)

Koufukuji Temple 興福寺

|

|

Dakkatsu Kanshitsu 脱活乾漆. Hollow Dry Lacquer. Also written Dakkanshitsu 脱乾漆, Dakkatsu Kanshitsuzou 脱活乾漆像, Dakkatsu Kanshitsu-zukuri 脱活乾漆造. A statue-making technique for lacquer sculpture, which emerged in the late Asuka period and flourished in the Nara era, but thereafter lost favor to wood. Clay is used to construct a rough inner-core model of the statue. This clay model is then wrapped in several layers of lacquer-soaked cloth, with each layer allowed to dry and harden before adding the next layer. Once hardened, the clay core is removed by scraping or by cutting the statue into segements (and reassembling it), resulting in a hollow and lightweight statue. A wood frame (shingi 心木) was often placed inside the hollow statue to prevent warping, and surface details were typically added using a paste called kokuso-urushi 木屎漆. See JAANUS Dakkatsukanshitsu for details. Dakkatsu Kanshitsu 脱活乾漆. Hollow Dry Lacquer. Also written Dakkanshitsu 脱乾漆, Dakkatsu Kanshitsuzou 脱活乾漆像, Dakkatsu Kanshitsu-zukuri 脱活乾漆造. A statue-making technique for lacquer sculpture, which emerged in the late Asuka period and flourished in the Nara era, but thereafter lost favor to wood. Clay is used to construct a rough inner-core model of the statue. This clay model is then wrapped in several layers of lacquer-soaked cloth, with each layer allowed to dry and harden before adding the next layer. Once hardened, the clay core is removed by scraping or by cutting the statue into segements (and reassembling it), resulting in a hollow and lightweight statue. A wood frame (shingi 心木) was often placed inside the hollow statue to prevent warping, and surface details were typically added using a paste called kokuso-urushi 木屎漆. See JAANUS Dakkatsukanshitsu for details.

Haku 箔. Literally “foil” or “leaf.” A general term referring to various techniques for adding metal decorations to Buddhist statues made of dry lacquer, clay, or wood. See above for details.

Kanshitsu 乾漆. Dry Lacquer. Also known as Kanshitsuzou 乾漆像, Kanshitsu-zukuri 乾漆造, Soku 即, or Kyoucho 夾紵. A method for making Buddhist images. The technique was brought to Japan from China in the late 7th century, rising to prominence in the Nara era. Two techniques were used. The first to appear was the “hollow dry lacquer” method (dakkatsu kanshitsu 脱活乾漆), followed later by the “wood-core dry lacquer” method (mokushin kanshitsu 木心乾漆). See JAANUS Kanshitsu for details.

Kirikane 切金. Also 截金. Literally "cut gold." A method popular in the Kamakura period for adorning lacquer statues with cut metal. See details above.

Kokuso Urushi 木屎漆. A paste made by mixing lacquer with flour and wood powder. Also known as Kokuso 木屎. The paste was then applied to dry lacquer statues to create surface details. It was also used as a repair material to treat damage or cracks on lacquer objects. See JAANUS Kokusourushi for details.

Mokushin Kanshitsu 木心乾漆. Wood-Core Dry Lacquer. Also known as Mokushin Kanshitsuzou 木心乾漆像 and Mokushin Kanshitsu-zukuri 木心乾漆造. A technique for making lacquer statues that emerged in the late 8th century, slightly after the emergence of the “hollow dry lacquer” method (dakkatsu kanshitsu 脱活乾漆). Construction began with the making of a roughly carved wooden core. The core was covered in several layers of lacquer-soaked cloth, and then allowed to dry and harden, after which facial features, draperies, and other surface details were molded using a paste called kokuso-urushi 木屎漆. Over time, the wooden core was carved with greater and greater precision, with the lacquer layer becoming thinner and thinner. This, some think, was an innovative early step leading to the prominence of all-wood statuary in the Heian era. In the 10th century, a new variation of the wood-core dry lacquer technique appeared. The wood core was no longer covered with a fiber-lacquer layer, but instead covered with a cloth layer and a paste called sabi-urushi 錆漆, the latter made of lacquer and ground stone powder. This paste was painstakingly applied as a ground coating to the sculpture, and then surface details were painted or done in gold leaf. See JAANUS Mokushin Kanshitsu for details.

Shingi 心木. Wooden frame that was typically placed inside hollow dry lacquer statues to prevent warping. See JAANUS Shingi for details.

Shippaku 漆箔. Method of affixing gold or silver foil to lacquer, and then applying this to statues made of dry-lacquer or wood. See details above.

|

|

|

STONE = 磨崖仏 (Magaibutsu) and 石仏 (Sekibutsu)

Stone was the chief material used for Buddhist images in China and India, whilst in Japan stone statues have never challenged the dominance of bronze and wood because appropriate stone materials were not so readily available. From the Heian Period (+794-1185) through the Kamakura Period (+1185 to 1333), the Kunisaki Peninsula in Kyushu thrived as a great hub of Buddhist culture in Japan. Countless stone statues, many carved into cliffs, still survive into the present day. This area is reported to contain more than 60% of Japan's magaibutsu (Buddhist images carved on large rock outcrops, cliffs, or in caves) and sekibutsu (free-standing, movable statues carved from stone). Below we present definitions and links to other site pages devoted to stone statuary in Japan.

|

|

Stone, Buddha Triad, Sansonzou 三尊像

H = 115.4 cm, Ishiidera 石位寺 (Nara)

Late 7th Century, Photo by Ogawa Kouzou, One of Japan’s oldest extant stone statues. |

|

Magaibutsu 磨崖仏

Buddhist images carved on large rock outcrops, cliffs, or in caves. Caves carved with Buddhist images that were large enough for people to enter and use for worship were specifically called Sekkutsu Jiin 石窟寺院 or Sekkutsuji 石窟寺 (both mean cave temple).

Kunisaki Peninsula is home to many magaibutsu. The rock-face was typically polished first, and then engraved lines (senkoku 線刻) were added to the image. The engraved lines were either low relief (ukibori 浮彫) or high relief (takanikubori 高肉彫). For numerous photos, see this site’s page on Magaibutsu. For more details, see JAANUS Magaibutsu.

Sekibutsu 石仏. Literally "Stone Buddha." A Buddhist image made in rock or stone. The term sekizou 石造 (stone carving) is also used. A free-standing movable Buddhist statue carved from stone. For more details, see JAANUS Sekibutsu.

|

Wooden Ganzo

Makura Honzon 枕本尊

at Kongoubuji 金剛峰寺

on Mt. Kouya 高野

Wakayama Prefecture

Sandalwood, +9th Century, China

Hinged on two sides and may be folded

H = 23.1 cm

|

|

Ganzō, Ganzou, Ganzo 龕像. Images carved in a stone niche. The term generally refers to high-relief Buddhist images carved into the stone walls of cave temples in both India and China, but it can also refer to small images carved in a wood niche. Another related term is Koganzō 小龕像, which refers specifically to stone niche carvings, but it is no longer used widely. When referring to wood ganzō, the object typically depicts a small Buddha image surrounded by many figures. The images are usually carved in high relief, and follow the traditional themes of the cave temples. The wooden niche was often small enough to be carried easily by wandering Buddhist monks. Many images from China were imported into Japan in this format, some hinged on both sides, allowing the owner to fold it shut when traveling. Most wood ganzō were made from sandalwood or another aromatic timber (see Danzō 壇像), with the images carved in fine detail with little use of pigment. In addition to many extant statues from the +9th century from China and Japan, numerous small ganzō statues from Korea and Central Asia have survived as well. The term Butsugan 仏龕 refers specifically to the niche itself rather than the images. The niche is considered a type of zushi 厨子 (tabernacle) to house sacred objects. Ganzō that are square and fold-up into a box shape are called Hakobutsu 箱仏. For more details, see JAANUS. Ganzō, Ganzou, Ganzo 龕像. Images carved in a stone niche. The term generally refers to high-relief Buddhist images carved into the stone walls of cave temples in both India and China, but it can also refer to small images carved in a wood niche. Another related term is Koganzō 小龕像, which refers specifically to stone niche carvings, but it is no longer used widely. When referring to wood ganzō, the object typically depicts a small Buddha image surrounded by many figures. The images are usually carved in high relief, and follow the traditional themes of the cave temples. The wooden niche was often small enough to be carried easily by wandering Buddhist monks. Many images from China were imported into Japan in this format, some hinged on both sides, allowing the owner to fold it shut when traveling. Most wood ganzō were made from sandalwood or another aromatic timber (see Danzō 壇像), with the images carved in fine detail with little use of pigment. In addition to many extant statues from the +9th century from China and Japan, numerous small ganzō statues from Korea and Central Asia have survived as well. The term Butsugan 仏龕 refers specifically to the niche itself rather than the images. The niche is considered a type of zushi 厨子 (tabernacle) to house sacred objects. Ganzō that are square and fold-up into a box shape are called Hakobutsu 箱仏. For more details, see JAANUS.

Stone-Related Pages at This Site

|

|

RESOURCES & WEB LINKS

- Shaping Faith: Japanese Ichiboku Buddhist Statues

Exhibition catalog of the Tokyo National Museum. The exhibit was held from Oct. 3 to Dec. 3, 2006. About 300 pages. Over 100 color photos. Japanese Language, but list of works and photos given in English. Published by Yomiuri Shimbun.

- Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System (JAANUS)

JAANUS, in my mind, is the best online database available on Japanese art history. Compiled by the late Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent, it covers both Buddhist and Shinto deities in great detail and contains over 8,000 entries.

- German-Language Resources by Dr. Gabi Greve

Explores the materials and techniques used to make statues.

- www.wood.co.jp/butsuzou/ken29.htm

Famous Japanese Buddhist statues listed next to the type of wood used in their construction. Japanese language only.

- ICHIBOKU SCULPTURES

www.lindquiststudios.com/ICHIBOKUS/Ichiboku-Titles.htm

See this site for more terms and definitions. Yama Uba, "old woman of the mountains," is an enigmatic mythic figure from the Heian period, sometimes a benevolent spirit, sometimes a nurturing mother. She made a home in the mountains where she reared her son Kintaro, a child of extraordinary strength. (He later became the renowned warrior Sakata no Kintoki.) Yama Uba is often depicted as a soslitary soul wandering through the hills, savoring the passage of seasons, and becoming one with the natural world.

|

|