|

|

|

|

OTHER TENBU (DEVA) IN JAPAN

Hindu Deities Adopted into Japanese Buddhism

THIS IS A SIDE PAGE

RETURN TO MAIN TENBU PAGE

What’s Here

- Kankiten. God of Conjugal Harmony, Child-Giving,

Long Life, and Restauranteers

- Idaten. Kitchen God, Protector of Monasteries and Monks

- Daijizaiten. Protector of Buddhist Teachings & Northeast

- Gigeiten. Goddess of the Arts

- Marishiten. Goddess of Wealth, the Warrior Class, and Entertainers

|

|

Kankiten 歓喜天 Kankiten 歓喜天

Also known as Kangiten, Kangiten-sama, Shōten 聖天 (Shouten, Shoten), Daishō Kangiten 大聖歓喜天, or Gaṇeśa / Ganesha / Ganesh. Also called the Deva of Bliss, Deva of Joy, Deva of Pleasure. Origin = India. In Japan, Kangiten is worshipped as a central object of devotion. Kangiten symbolizes conjugal affection, and is thus prayed to by couples hoping for children. Statues of this deity are relatively rare in Japan -- most are kept hidden from public view and used in secretive rituals of the Tendai and Shingon sects of Esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō 密教). Kangiten statues in Japan clearly reflect the deity’s Hindu origins, for in India the deity is known as the elephant-headed Gaṇeśa. In Japan, Kankiten is typically depicted with an elephant’s head and human body, or as a pair of two-armed, elephant-headed deities in embrace.

Kankiten

Below text courtesy JAANUS

The elephant-headed Indian deity Ganesa. A son of Siva (Shiva) still worshipped as a deity who foils obstacles to ones actions and grants good fortune to new beginnings. He appears in the Ryoukai Mandala 両界曼荼羅 as an elephant-headed deity called Binayakaten 毘那夜迦天. In China and Japan he came to be revered under the the name of Kangiten. Although in texts, two, four and six-armed forms are mentioned, in Japan Kangiten is usually shown as a pair of two-armed, elephant-headed deities in embrace. Images of Kangiten are rare and many are kept as secret images in temples and shrines. Many are small, and made of metal because his ritual involves pouring oil over the images. The ritual associated with Kangiten was secret and was part of other ritual observances, such as the Goshichinichi no Mishuhou 後七日の御修法. In popular worship he signifies conjugal harmony and long life. There is an iconographic drawing of Kangiten in Touji Temple 東寺大自在天秘仏, Kyoto, by Chinkai 珍海 (1091-1152).

Kangiten

Below text from Digital Dictionary of Buddhism

Sign in with user name = guest. The joyful devas, or devas of pleasure, represented as two figures embracing each other, with elephants' heads and human bodies; the two embracing figures are interpreted as Gaṇeśa (the eldest son of Śiva) and an incarnation of Avalokitêśvara; the elephant-head represents Gaṇeśa; the origin is older than the Avalokitêśvara idea and seems to be a derivation from the Śivaitic linga-worship. (Skt. nandikêśvara, *gaṅa-pati) Also written 大聖歡喜天; 聖天; 大聖天. Transliterated as 俄那鉢底 and 誐那鉢底. 〔雜阿含經 T 99.2.227a8〕 [Charles Muller; source(s): Soothill, Hirakawa, JEBD]. Other readings: Chn = Huānxǐtiān Tiān 歡喜天; Krn = Hwanhui Cheon 환희천

Kankiten in Japan

Below text courtesy Gabi Greve

In esoteric Buddhism, this deity is often shown as two human-bodied figures with elephant heads, who are embracing each other. As such, they are venerated with prayers for good marriage and children. The male form is thought to be the oldest son of Daijizaiten 大自在天. Daijizaiten is one of the many manifestations of the Hindu god Shiva, the lord of cosmic destruction (also known as Ishana, one of the 12 Buddhist Deva). The eldest son is also known as Daibōjin 大暴神, the "great wild god." To calm this wild deity, the female form represents an incarnation of the eleven-headed Kannon Bosatsu, who converted this wild god to Buddhism. She is capable of intensive meditation (kanjin 觀心) and thus calms his wildness. So the name of these two is Deity of Joy (Kankiten, Kangiten). The statues of these embracing deities are usually not shown to the public, because of the sexual implication. They are kept in separate shrines behind closed doors, the so-called Secret Statues (hibutsu 秘仏). There are more than 250 temples in Japan where Ganesh (Kankiten) is venerated. In Kamakura, at the Hōkaijji Temple 宝戒寺, is a Kangiten Hall where you can find the oldest statue of a Kankiten in Japan. This image is said to be especially powerful and therefore kept locked in a tabernakel since 1333. This is located in a separate hall for the deity. In special exorcistic rituals for these “secret” deities, the statues are usually poored over with oil, mostly hot oil. Kankiten statues are also venerated by people in the restaurant business. <end story by Gabi Greve>

Ganesh Worship in Japan

Below Text courtesy Satish Purohit

Scholars commonly date the presence of Ganesha (Gaṇeśa, Ganesh) in Japan with the age of Kūkai (774- 834), the founder of the Shingon sect of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism. Ganesha’s most popular form in Japan is the dual-Vinayaka or the Embracing Kangiten. Two tall figures, elephant headed but human bodied, male and female, stand in embrace. The female wears a jeweled crown, a patched monks robe, and a red surplice. Also called the Deva of Bliss (Ganapati), Kankiten is invoked both for enlightenment and for worldly gains. Kakiten-Vinayaka is offered "bliss buns" (made from curds, honey and parched flour), radishes, wine, and fresh fruits. The offerings are later partaken in the same spirit as Hindus take prasad. Whosoever fulfills the rituals of the dual Kangiten is believed to attain success in all worldly endeavors. <Editor’s Note: As for the “bliss buns,” I’m not sure if Purohit-san is talking about Japan or India.>

Kankiten: Japan’s Restaurant Industry

Below text courtesy Butuzou.co.jp.

In Indian myth, this deity’s name means tribal chief. Once incorporated into Buddhism, Kangiten was considered the child of Daijizaiten and the brother of Idaten. A lot of ordinary Japanese people believe in Kangiten, especially those involved in the food and drink business (e.g., restaurants, bars). Sometimes Kangiten is depicted as two human bodies with elephant heads; sometimes as a single body with an elephant head, and sometimes as a couple in which the husband has an elephant head and the wife has the head of a wild boar.

RITUAL: Pouring Hot Oil on Kankiten

Story by Gabi Greve. Here is a mysterious story I heard in a temple in Kamakura. For special exorcistic rituals of esoteric Buddhism heated oil is poured over a Buddha statue. The statue in question was a secret statue, so a Kakebotoke, or substitue object, had to be used. Since the Kakebotoke statue of this temple had just been newly made and was quite pretty, the priest wanted to spare it this fate. He decided to reflect the statue in a mirror and poor the heated oil over the mirror. It seems the gods accepted this sacrificial offer of a substitute with another substitute and peace returned to the poor soul for which the ritual was performed.

You want to know why this ritual had to be performed? Here’s the story I heard. During the early Edo period, a young woman who lived in Kamakura close to this temple had made a wish to the powerful god of this particluar temple (Kangiten) to grant her a child. She soon gave birth to a beautiful baby boy, but died shortly after that. Since it is the custom to go back to the temple and thank the god for a granted favor (o-rei mairi), she could not perform this ceremony and her poor soul was hanging in limbo for quite a while. Just after World War II another woman, Mrs. K. who lived close to the temple, started to have the same dream every night: A young woman appeared at her pillow, telling her the above story and asked her to have a ritual performed to pacify her soul. "If you help me, I will show my gratitude for your act!" the young woman promised.

So, after consulting with the temple priest, the ritual to pacify the soul of the young mother was performed by pouring hot oil on the mirror to substitute for the substitute, but the god was pacified anyway and the soul of the young woman could proceed to heaven. She appeared just one more time at the pillow of Mrs. K., thanked her again and promised to do something good for her.

Now, you ask, what good did she do for Mrs. K? The temple in Kamakura is Hōkaiji 宝戒寺, close to Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine. The Buddha statue in question is one of a Kankiten, a very powerful statue of the elephant-headed Ganesh in embrace with his alter-ego. At the southeast corner of the temple grounds or on the right of the main hall stands a small structure, in which the statue of Kangiten (Skt. = Nandikesvara) is enshrined. The statue (152 cm. in height) was made during the first half of the 14th century. It is unique in that it has two elephant faces on two human bodies hugging each other. Originally, Kangiten was a god of Hinduism and was later employed by Buddhism. In Japanese folklore, Kangiten is believed to invite conjugal affection and bless couples with children. Unfortunately, the statue is not on public display and the door is always closed.

Anyway, the priest at Hōkaiji will tell you that it is dangerous to make a wish at this Kangiten, because if you forget your “Thank-You-Return-Visit,” something bad will happen, as in the story above. Finally, who was Mrs. K? That was the wife of the famous poet Kawabata Yasunari 川端康成 (1899-1972). After 1930, the Kawabatas lived close to this Kamakura temple for a time. In 1968 Yasunari received the Nobel Prize and our story happened just a year before that. So Mrs. Kawabata is convinced that her dream and the reward she merited was the Nobel Prize for her husband! This is how I heard it from the wife of the head priest about 15 years ago. <end story by Gabi Greve>

|

|

At Miyajima, Japan

Photo: Craig D. Rice, Ameeta Sony, & the UniYatra Group

The central statue is Kankiten (in Hindu form).

Such statues are generally hidden from view,

and are relatively rare in Japan.

|

Kankiten Statue near entrance to Fukuoka Tower.

20 minutes from Nishi-Arashi Station 西新駅.

Photo courtesy this Japanese web site.

|

|

RESOURCES ON KANKITEN (Elephant-Headed Deity)

|

|

Idaten

Manpukuji Temple, Kyoto

Kamakura Era

Idaten, Gifu Precture

Tsushiji Temple, Kamakura Era

Photo this J-site |

|

IDATEN 韋駄天 or 違駄天 IDATEN 韋駄天 or 違駄天

God of the Kitchen and

Protector of Monastaries and Monks

- Origin: Skanda (Skt.) of Hindu Myth

- Mantra (Japanese): オン ケンダヤ ソワカ

Said to prevent theft against the person chanting the mantra.

- Once incorporated into Buddhism, Idaten was considered the child of Daijizaiten and the brother of the elephant-headed Kankiten.

IDATEN. Below text courtesy JAANUS. The Indian deity Skanda, son of Siva (Shiva) and general of his army, who became a protector of the Dharma in Buddhism. The names Sukanda 塞建駄, Shikenda 私建陀, Kenda 建陀, and Ida Shougun 韋駄将軍 (General Ida) are also used. Idaten is mentioned in the sutras KONKOUMYOUKYOU 金光明経 and DAIHATSUNEHANKYOU 大般涅槃経, but his appearance is not described. It is thought that in China he was conflated with a famous Chinese general and that his characteristic appearance, wearing armor, with a sword or baton resting on his forearms and his hands clasped together in the Veneration Mudra (gasshou 合掌), is derived from this. Although in Buddhist texts Idaten is a protector of Buddhist teachings, in various parts of China, especially in Chan (Zen), he was considered a protector of monasteries and monks. In Japan he was enshrined in Zen living quarters and kitchens. The oldest example of his image is the Song dynasty sculpture to the right of the sharihoutou 舎利宝塔 in the shariden 舎利殿 of Sennyuuji Temple 泉涌寺 in Kyoto, which was brought to Japan from China by Tankai 湛海 in 1255 along with relics from Taishan 泰山 (Jp: Taizan) and Bailiansi 白蓮寺 (Jp: Byakurenji). Idaten has a close relationship with relics because of the story that while guarding the Buddha's ashes a demon tried to steal them, whereupon he chased the demon away and retrieved the ashes. Other examples include the Kamakura period sculpture in Tsushinji Temple 乙津寺 in Gifu prefecture, and the sculpture in Manpukuji Temple 万福寺, Kyoto, (possibly made by the Chinese artist Fan Daosheng 笵道生 [Jp: Han Dousei, 1637-70] who was active at Manpukuji). There is also a Kamakura-period painting at Sennyuuji Temple.

IDATEN. Below text courtesy Buddhistinformation.com. Idaten is a god of the kitchen who looks after the provisions of the Buddhist brotherhood. The original Sanskrit term for Idaten seems to be Skanda (and not Veda as may be suggested from i-da or wei-t'o). He is one of the eight generals belonging to Virudhaka, the guardian god of the southern quarter. He is a great runner and wherever there is trouble he is instantly found there. In the Chinese monastery he occupies an important seat in the hall of the four guardian gods, but in Japan he is in a little shrine attached to the monks' dining-room.

IDATEN. Below text courtesy Kondo Tadahiro.Idaten (Skt. = Skanda) is one of many guardian deities. Known as a swift runner, for legend asserts that he ran with great speed to catch the thieves who stole the ashes of the deceased Historical Buddha. Statues of Idaten are often installed in kitchens of Zen temples or the living quarters of Zen priests. The statue of Idaten at Jochi Temple in Kamakura is 87 centimeters in height, and was carved in the 14th century. Sculptor unknown. It was designated as an Important Cultural Asset by the City of Kamakura.

|

Idaten

Modern Wood Sculpture

Photo this J-site

|

Idaten; Height 24 cm. Edo era.

No location given by source.

Photo this J-Site

|

Idaten Stone Statue

Located at Nishimitsu Temple (Tokyo)

Statue made on behalf of Tōdō Takatora (1556-1630), commander of the Japanese navy in the invasion of Korea called "Bunroku Keicho no Eki."

Photo this J-site

|

|

|

|

|

Daijizaiten 大自在天

Below text courtesy JAANUS

Translation of Sanskrit Mahesvara. Also transliterated as Makeishura 摩醯首羅, one of the many names of Shiva (Siva), who, along with Brahma (Bonten 梵天) and Vishnu (Visnu) is one of the three chief gods of Hinduism. Presiding in particular over cosmic destruction, Shiva is regarded as the supreme Hindu deity.

Daijizaiten was adopted into Buddhism as a protector of the Buddhist teachings and is also counted among the Guardians of the Eight Directions (Happōten 八方天) , presiding over the northeast corner, and thus figuring among the Twelve Deva (Jūniten 十二天), consisting of the eight guardians plus the guardians of heaven, earth, sun and moon. In this context he appears under the name Ishana 伊舎那.

According to the traditions of Esoteric Buddhism, before becoming a Buddhist tutelary deity, Daijizaiten was first vanquished by Gōsanze Myō-ō 降三世明王, the conqueror of earthly desires. As a result he and his consort Uma 烏摩 (Skt: Uma) often appear in representations of Gōsanze, who is shown trampling them underfoot.

Although Daijizaiten did not become the object of an independent cult in China and Japan, a number of many-faced and many-armed forms are described in ritual texts, while in the Womb World Mandala (Taizōkai Mandala 胎蔵界曼荼羅) he appears in the Gekongōbuin 外金剛部院 with two arms, dark-red in colour, seated on a dark-blue buffalo, and accompanied by Uma, also seated on a buffalo. Gigeiten 技芸天, a minor deity and patroness of the arts, is believed to have been born from his hairline. < end quote by JAANUS >

|

|

|

Gigeiten, Wood.

Akishinodera 秋篠寺 (Nara)

Photo this J-site

|

|

Gigeiten 技芸天 Gigeiten 技芸天

Goddess of the Arts. A minor Buddhist deity revered as patroness of the arts. In Japan, she has been largely supplanted by Benzaiten, the popular Buddhist patroness of music, poetry, learning, and art.

Says JAANUS: According to the GIGEI TENNYO NENJUHO 技芸天女念誦法, she was born from the hairline of Daijizaiten 大自在天 (Skt; Mahesvara) while he was playing music, whence she is also known as Daijizaitennyo 大自在天女 or Makeishura-chōshō-tennyo 摩醯首羅頂生天女 (Goddess born from the crown of Mahesvara).

She is described in literature as holding celestial flowers in her raised left hand, and the hem of her robes with her right hand. However the reknowned sculpture at Akishinodera 秋篠寺 (Nara), with a dry-lacquer head dating from the Nara period attached to a wooden carved body dating from the Kamakura period, takes the form of a bodhisattva (bosatsu), with the right hand raised and the left hand fingering her robes.

Some scholars do question whether this figure actually represents Gigeiten at all. There are very few representations of Gigeiten as an object of worship in Japan, but more recently a large wooden image of her was produced by Takeuchi Hisakazu 竹内久一 (1857-1916) for the 1893 World Exposition in Chicago. |

|

|

|

MANTRA (Japanese)

おん まりしえい そわか

On Marishi-ei Sowaka

Literally = Hail Marishiten

Esoteric Seed Syllable

Pronounced MA in Japan

Courtesy this J-Site

SPELLINGS

Skt = Mārīcī, Marici

Jp = Marishiten, Marishi

Chn = 摩利支, 摩梨支, 摩里支, 末利支

Chn = Mólìzhī tiān, Mólìzhī, Molizhi

Chn = Mo-li-chih t'ien, Mo-li-chih

Korean = 마리지천, Krn = Mariji cheon

Korean = Marichi ch'ŏn, Mariji

Santen 三天 = Three Celestials

Marishiten in Japan is revered as a tutelary deity of the warrior class. In later centuries, she was worshipped as a goddess of wealth and prosperity among merchants and entertainers. She was counted along with Daikokuten and Benzaiten as one of "three deities" (Santen 三天) invoked for good fortune in the Edo period. Marishiten is a member of the TENBU group, but her worship has been largely supplanted by Benzaiten.

Line Drawings, Butsuzō-zu-i (1690)

Line Drawings, Butsuzō-zu-i (1690)

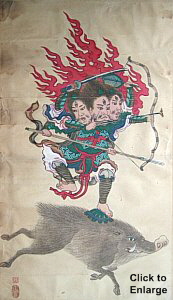

3-Headed Marishiten atop boar.

Rokumanji Temple 六万寺.

Shikoku Prefecture. Rare painting.

Muromachi Era (1392 - 1568).

Photo this J-site.

Sow, Boar, or Pig? Many sources say Marishiten stands atop a boar, while many others say sow, and yet others pig. Despite the lack of clarity, most artwork shows Marishiten atop a “tusked” swine. Consider this -- a female pig is a sow, a male pig is a boar. But boar is also a word for the wild, tusked, and hairier swine. It is therefore possible to say that a boar is a sow. See Khandro.net for much more on the iconography of the pig, sow, and boar in religious artwork. 亥の日=摩利支天

|

|

|

|

MARISHITEN 摩利支天 MARISHITEN 摩利支天

Origin = Hindu Deity of India

One of 20 Celestials (Nijūten 二十天)

One of Three Celestials (Santen 三天; see sidebar)

God / Goddess of prosperity, the warrior class, and entertainers in Japan. Depicted as a male or female warrior, often with three heads and multiple arms holding weapons, standing or sitting atop a sow or boar, or driving a chariot drawn by seven pigs. In Japan, this deity is also sometimes depicted as a beautiful female goddess of fortune standing or sitting on a lotus. In her female form, she is the consort of Dainichi Nyorai (Skt. = Vairocana), the Great Solar Buddha. In this role, she is the harbinger of Dainichi, the Goddess of Dawn, a personification of light, one identified with the blinding rays and fire of the rising sun, and thus with the power of invisibility and mirage. Marishiten’s powers of illusion were probably the main reason she was adopted as the tutelary deity of street magicians and entertainers. Her mount, the boar, “represents audacious advance without fear, a desirable quality for a warrior.” <Source: Michael Ashkenazi>

Introduced to Japan along with the Shingon and Tendai sects of Esoteric Buddhism in the early 9th century, s/he was worshipped by warriors, especially archers, from the middle ages onward for the gift of invisibility. Minamoto Yoritomo 源頼朝 (+1147-1199), one of Japan’s most lauded military geniuses and the first shōgun 将軍 of the Kamakura era (1185-1332), reportedly had an idol of Marishiten made to protect him in battle. This idol is now said to be housed at the Kantsūji Temple 感通寺 in Tokyo’s Shinjuku ward <source: Edo Meisho Zue>. The famous military leader Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (1542-1616), the first shōgun of the Edo period (1615-1868), carried a small wooden Marishi charm at all times. The charm is now said to be a treasure of Shizuoka Sengen Jinja 静岡浅間神社 in Shizuoka. At Sengaku-ji Temple 泉岳寺 in Tokyo, the grave of the 47 Rōnin (see Chūshingura) is guarded by an effigy of Marishiten.

In Japanese artwork, Marishi is typically portrayed in an aggressive, warrior-like pose holding weapons of war. Those who worship Marishiten are said to be free of danger from all misfortune and evil, robbers, natural disaster, poisonous drugs, and other harm. It is also said s/he cures anal diseases and possession by spirits, relieves difficult deliveries, and helps in resolving differences. Those who recite Marishi’s mantra are promised that all their wishes will be fulfilled. S/he is also identified with the seven stars of the Little Bear (Little Dipper) constellation, which perhaps explains why s/he drives a chariot drawn by seven pigs. [Editor’s Note: Some sources say the Great Bear (Big Dipper); this needs checking.]

Marishiten’s cult peaked in the Edo era but declined thereafter owing to the dismantling of the feudal system, to the abolishment of the samurai class, and to the rising popularity of goddess Benzaiten, who has largely supplanted Marishiten as an object of veneration in modern times.

Says Saroj Kumar Chaudhuri: “Indian mythology projects Marīci as one of the ten mind-born children of Brahmā (Jp. = Bonten). The word Marīci itself appears in the Rig Veda, meaning ‘ray of light of the sun or the moon.’ In Japan, however, this deity was treated as a female divinity. She enjoyed some popularity among practitioners of martial arts and entertainers who prayed to her for success. Otherwise, she had little popularity in Japan. She is virtually ignored in popular [Japanese] literature. She is said to be positioned in fornt of the sun and hence invisible. Evils can be eliminated by chanting her mantra. She fought taking the side of Indra (Jp. = Taishakuten) when the Asura attacked Indra to recover the Asura king’s daughter (then Indra’s consort). In the 12th century, Marīci was worshipped in China for protection. From around this time, she became popular in Japan also, especially among warriors and entertainers.” <end quote>

Says William Edward Soothill: “Spelled Marīci (Sanskrit). Rays of light, the sun’s rays, said to go before the sun; mirage. A goddess, independent and sovereign, protectress against all violence and peril. In Brahmanic mythology, the personification of light, offspring of Brahmā, parent of Sūrya. Among Chinese Buddhists Marīci is represented as a female with eight arms, two of which are holding aloft emblems of sun and moon, and worshipped as goddess of light and as the guardian of all nations, whom she protects from the fury of war. She is addressed as 天后 queen of heaven, or as 斗姥 (literally “mother of the Southern Measure μλρστζ or Sagittarī), and identified with Tchundi and with Mahēśvarī, the wife of Maheśvara, and has therefore the attribute Mātrikā -- Mother of the Myriad Buddha. Taoists address her as Queen of Heaven.” <end quote> Soothill also identifies Marīci with Saptakotibuddha-mātṛ (Shichikuchi Butsumo Son 七倶胝佛母尊), the fabulous mother of seven koṭīs of Buddhas (70 million Buddha). Other entrees in Soothill’s dictionary say she is known as well as Candī / Cundi 準提 / 准胝 / 尊提 or as Cundī-Guanyin 準提觀音 (a form of Kannon). In Brahmanic mythology, Candī / Cundi is a vindictive form of Hindu goddess Durgā, who can appear in the form of a wild boar.

Says the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (sign in with user name = guest): “Transliteration of Sanskrit Marici. An Indian goddess of the morning sun adopted into the Buddhist pantheon. She rides a chariot drawn by seven pigs, her charioteer either the Hindu deity Rhu or a goddess with no legs. She is the consort of Vairocana (Jp. = Dainichi), though rarely shown in yab-yum with him. She is associated with the constellations of Sagittarius and the Little Bear. She is shown with three faces and eight hands, either in her chariot or simply standing on the back of a sow. She is one of the 20 Celestials 二十天.” <end quote>

Says JAANUS. Marishiten is the name of a Buddhist goddess representing an amalgamation of several Hindu antecedents, primarily the god Marici, who is considered to have been a son of Brahma (Bonten 梵天) or one of the ten patriarchs created by the first lawgiver Manu. The deity assumed female form on adoption into Japanese Buddhism. Since Marici means "light" or "mirage," Marici was regarded as a deification of mirages and being thus invisible or difficult to see was invoked in order to escape the notice of one's enemies. This martial aspect has been carried over in the cult of Marishiten in Japan, where she came to be revered as a tutelary deity of the warrior class. Later she was also worshipped as a goddess of wealth and prosperity among the merchant class, being counted along with Daikokuten 大黒天 and Benzaiten 弁財天 as one of a trio of "three deities" (Santen 三天) invoked for such a purpose during the Edo period. She assumes a variety of forms and may have one, three, five or six faces and two, six, eight, ten or twelve arms; in her many-faced manifestations, one of her faces is that of a sow, and she rides either a sow or a chariot drawn by seven pigs. Images of Marishiten are common in India, but there are few examples in Japan. Shōtakuin 聖沢院 (Kyoto) has a polychrome painting said to be of Korean provenance, while Tokudaiji Temple 徳大寺 (Tokyo) is dedicated to a large image of her dubiously attributed to Shōtoku Taishi 聖徳太子 (574-622 AD). The Nispannayogavali also describes a mandala 曼荼羅 centered on Marishiten. <end quote> Note: The Flammarion Guide says her mandala is composed of two interlaced triangles with her image in the center, dancing, surrounded by four Dakinis.

Says the Flammarion Guide: “She was worshipped in Japan during the Middle Ages by warriors, especially archers, who often wore her image, protecting those who invoked her name, and making them invisible in danger. People can neither see her nor harm her. She was also worshipped by disciples of Zen and Nichiren. The Japanese have mostly forgotten her now, and she is worshipped only very occasionally. She assumes various forms [in Japan]. <end quote>

|

Marishiten Dōsojinn

Near Daiunji Temple 大雲寺

Photo courtesy this J-site.

At Daiunji Temple near Kyoto.

|

Miura Family Collection, 1793

Source: This J-site

|

Marishiten Painting, 1893

by Ono Kansai 小野閑哉

Source: This J-site

|

|

Marishiten Painting

Hong Kong Art & Collectibles Club

Source: This E-site

|

Marishiten Painting

Kōyasan. No date given.

Source: Museum Reihōkan Kōyasan

高野山霊宝館 (J-Site)

|

Marishiten Painting

Kōyasan. No date given.

Source: Museum Reihōkan Kōyasan

高野山霊宝館 (J-Site)

|

|

Marishiten, Modern Statue

Source: This J-site

|

Modern

Protective Sandalwood Amulet

Available for online purchase at

Buddhist-Artwork.com

|

Marishiten Protective Amulet

Sold at historic site linked to Yamamoto Kansuke 山本 勘助, a famous 16th-century samurai. Source: This J-site

|

|

3-Headed, Six Armed, 7 Pigs

Kaizenji Temple 開善寺, Iida City, Nagano

Left head = gold sow, right = bosatsu.

Wood, Dated to 1692 (元禄五年)

Source: This J-site

|

India, 10th Century

Stone, 3-Headed, 8-Armed,

Standing atop seven pigs.

Goddess of the Sun.

Nat’l Museum of New Deli

Source: This J-site

|

Marishi (masculine form) riding boar.

Musée Guimet, Paris

No date given. H = 39 cm.

Source: This French site

|

|

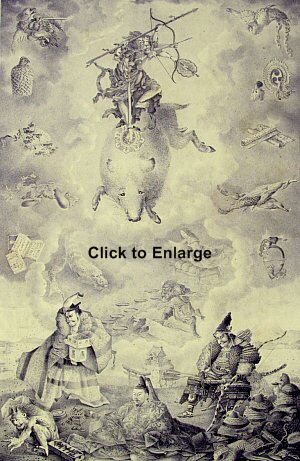

Marishiten as reproduced by Philipp Franz von Siebold.

Nippon Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan. Leiden (1831 CE)

Photo Page | Index Page | Top Page | Text Search

Says Professor Evgeny Steiner (SOAS):

"This Siebold concoction of various images from Hokusai's Manga (Marishiten is taken from v. 6, pp. 13l-14r with no reference to Hokusai) is quite interesting. Siebold associates Marishiten with Mars and Ares. Modern scholars do not support this etymology."

|

|

Marishiten Sutras & Texts Marishiten Sutras & Texts

Special thanks to scholar David A. Hall for assistance in putting together these references.

- (Fó shuō) Mólìzhītiān púsà tuóluóní jīng

『(佛説) 摩利支天菩薩陀羅尼經』. Spell of the Goddess Bodhisattvā Mārīcī. Translated by Amoghavajra (Bùkōng Jīngāng 不空金剛). T. 1255[A], XXI: 259-260. 8th century. Known in Japan as the Bussetsu Marishiten Bosatsu Darani Kyō. This text says Marishiten travels in front of the sun and thus can’t be seen. Those who recite Marishiten’s matra shall have all wishes fulfilled.

- (Fó shuō) Mólìzhītiān jīng. 『(佛説) 摩利支天經』. Discourse on the Goddess Mārīcī. Translated by Amoghavajra (Bùkōng Jīngāng 不空金剛). T. 1255[B], XXI: 260-261. 8th century. Known in Japan as the Bussetsu Marishiten Gyō or more simply as the Marishiten Gyō. This text says those who chant Marishiten’s mantra one-hundred-thousand times, make a mandala, draw a picture of the deity and place the picture on an alter, make various prescribed offerings, and perform “homa” (fire ritual), shall have all wishes granted. Holds fan with symbol of Buddhist faith (Svastikah 卍; pronounced Kyōji 胸字 in Japan), with image of sun on the four edges of the Svastikah; flames appear to emanate from the fan; fan symbolizes Marishi’s ability to remain invisible and also represents the blowing away of worry, pain, and discontent; a small idol should be carried at all times, except when answering call of nature; monks should keep idol inside their robes, lay people inside their hair topknot; they should tell no one about the idol, and keep it a strict secret. Marishiten saves such believers from all misfortune, fulfills all wishes, cures anal diseases and possession by spirits, relieves difficult deliveries, helps in resolving differences, and bestows wealth to followers. <Source: Saroj>

- (Fó shuō) Tuóluóní jí jīng 『(佛説) 陀羅尼集經・(佛説)摩利支天經』. The Collected Dhāraṇī-sūtras— Section 10: The Buddha’s Discourse on the Goddess Mārīcī. Translated by Atikūa. T. 901, XVIII: 869-874. 7th century (654 AD). Known in Japan as the Bussetsu Marishiten Gyō or alternatively as the Bussetsu Darani Jūkkyō.

- (Fó shuō) Dà Mólìzhī púsà jīng 『(佛説) 大摩里支菩薩經』. Exalted Bodhisattvā Mārīcī. Translated by Tian Xizai. T. 1257, XXI: 262-285. 10th century, approximately 986-987 AD. Known in Japan as the Dai Marishi Bosatsu Kyō. This text says Marishiten is dressed in a white robe, has pagoda on her head, holds a flowering branch of the asoka tree, and sits on a golden boar. Also says Marishiten emits golden light, wears jewelry and heavenly robe, and has six hands and three faces (with three eyes on each face). Left hand holding bow, rope, and branch of asoka tree. Right hand holding arrow, needle, and club.

- Mólìzhī típó huámán jīng 『末利支提婆華鬘經』. Mārīcī, the Flower-wreathed Goddess. Translated by Amoghavajra (Bukong 不空). T. 1254, XXI: 255-259. 8th century. Known in Japan as the Marishi Daibakeman Gyō.

- (Fó shuō) Mólìzhītiān tuóluóní zhòu jīng 『摩利支天陀羅尼咒經』. Incantation of the Goddess-Spell Mārīcī. Anon. translator. T. 1256, XXI: 261-262. 6th century.

- Mólìzhī púsà lüè niànsòngfǎ 『摩利支菩薩略念誦法』. Abbreviated Recitation Method of the Mārīcī-bodhisattvā Spell. Translated by Amoghavajra (Bùkōng Jīngāng 不空金剛). T. 1258, XXI: 285-285b. 8th century.

- Mólìzhītiān yíguǐ 『摩利支天儀軌』. Goddess Mārīcī Ritual Guide. Ritual manual attributed to Bùkōng Jīngāng 不空金剛. 8th century.

- Mólìzhītiān yīyìnfǎ 『摩利支天一印法』. Anon. translator. T. 1259, XXI: 285c. Approx. 8th century.

- Mólìzhītiān yíguǐ 『摩利支天儀軌』. Goddess Mārīcī Ritual Guide. Ritual manual attributed to Bùkōng Jīngāng 不空金剛. 8th century. Known in Japan as the Marishiten Giki.

- Marishi Yōki 摩利支要記. By 9th century monk Annen. Says Marishiten belongs to the Vairocana group, i.e., the group of the Sun God / Solar Buddha named Dainichi Nyorai.

- Marishi Hi Hō 未利支秘法. “Secret Rituals of Marishiten.” By Tendai monk Annen, 9th Century. No longer extant, but known through citations in other texts.

- Kakuzenshō 覚禅鈔 (1217 AD). Tells story about battle between Indra and Asura king over the king’s beautiful daughter. Marishi appears as three-year old child, hides the palaces of the sun and moon, and the Asura are defeated.

- Numerous Japanese sources say Marishiten should be worshipped at the time of solar and lunar eclipses, on the 8th day of the waxing and waning phases of the moon, on New Year day, and on the Day of Kōshi (37th day of the Zodiac’s sexagenaric cycle). Those who have renounced the world should worship her at dawn every day. Laity should worship her on the six days of fasting during the waning phase of the moon (8th, 14th, 15th, 23rd, 29th, & 30th days of the month). <Source: Saroj>

Main Sanskrit Texts Concerning Mārīcī / Marishiten

- Śikṣāsamuccaya of Śantideva (c.800). Contains a Mārīcī section.

- Ārya-mārīcī-nāma-dhāraṇī (10th century). There are a number of other miscellaneous copies of the Mārīcī-dhāraṇī-sūtras of which the dates are unknown.

- Niṣpannayogāvalī (of Mahāpaṇḍita Abhyākaragupta) (c.1100). Contains a Mārīcī mandala.

- Sādhanamālā (c.1165). Contains eighteen sādhanas (ritual invocation texts) which mention various forms of Mārīcī; sixteen of them are devoted to her.

Other Mārīcī / Marishiten Resources

- Saroj Kumar Chaudhuri, Hindu Gods and Goddesses in Japan. Vedams, 2003, pp. 116-122. ISBN : 81-7936-009-1. See partial preview of book at Google Online Book Preview.

- Hall, David Avalon. The Buddhist Goddess Marishiten: A Study of the Evolution and Impact of her Cult on the Japanese Warrior. Published by Brill, 2013. Professor Hall (Ph.D., 1990, U.C. Berkeley) is a teacher and director of the CyberWatch Center at Montgomery College, MD. He has published translations and articles on Japanese Buddhist and warrior culture including An Encyclopedia of Japanese Martial Arts (Kodansha, 2012).

- Hall, David Avalon. Marishiten: Buddhism and the Warrior Goddess. Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1990, 441 pages; AAT 9103711. His dissertation can be bought online at Proquest.com.

- Hall, David Avalon. "Martial Aspects of the Buddhist Mārīcī in Sixth Century China." Annual of The Institute for Comprehensive Studies of Buddhism, Taisho Univ., No. 13. (March 1991): 182-199.

- Hall, David Avalon. "Marishiten: Buddhist Influences on Combative Behavior" in Koryu Bujutsu: Classical Warrior Traditions of Japan. Koryu Books, 1997, pp. 87-119.

- Kohalyk, Chad. Religion on the Battlefield: Esoteric Buddhism and the Japanese Warrior. 22 Feb. 2006.

- Buddhism (Flammarion Iconographic Guides)

, by Louis Frederic, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. Pages 224 - 226. , by Louis Frederic, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. Pages 224 - 226.

- Amano, Sadakage 天野信景 (1633-1733), Shiojiri 塩尻, Volume 2, Nihon Zuihitsu Taisei 日本隋筆大成, 3-14, 吉川弘文館, Tokyo, 1977, p. 444.

- Edo Meisho Zue 江戸名所図会 (Guide to Famous Edo Sites). 1836. See English description.

- Ashkenazi, Michael. “Handbook of Japanese Mythology.” Published 2003 by ABC CLIO, p. 215.

- Marishi Santen. By Gabi Greve. Says Gabi: “The warrior Kusunoki Masashige 楠木正成 (died 1337) had a small statue of Marishiten in the decoration of his helmet. Other samurai like Yamamoto Kansuke 山本勘助 (16th century) and Maeda Toshiie 前田利家 (16th century) did as well. Another common helmet design was to display the Svastikah 卍 (symbol of Buddhist faith; also an emblem of Marishiten) or a boar on the helmet. See above for more on Marishiten and 卍.

- The Big Book of Reiki Symbols: The Spiritual Transition of Symbols and Mantras of the Usui System of Natural Healing. By Mark Hosak, Walter Luebeck, Christine M. Grimm. Lotus Press, 2007. Includes sections on Marishiten’s mudra and meditation practices.

- Marishiten Mantra and Seed Syllable (J-site)

- Photos of the Boar at Marishiten Sanctuaries (J-site)

- Pig, Sow, and Boar Symbolism. From Khandro.net.

Marishiten Sanctuaries in Japan

Marishiten’s main centers of devotion in Japan are known as the “Three Great Marishiten Sanctuaries,” or Nihon Sandai Marishiten 日本三大摩利支天.

- Hōzenji Temple 宝泉寺 (Kanazawa City, Ishikawa Pref.). Shingon Sect. The powerful Maeda 前田 military clan adopted Marishiten as their tutelary deity and worshipped her at this location. Photos of Hōzenji.

- Tokudaiji Temple 徳大寺 (Tokyo). Nichiren Sect. Dedicated to large effigy of Marishiten dubiously attributed to Shōtoku Taishi 聖徳太子 (574-622 AD). Photos 1 | Photos 2

- Kenninji Temple 建仁寺 ・ Zenkyo-an Sub-Temple 禅居庵 (Kyoto). Rinzai Zen Sect. Photos.

Other Marishiten Centers of Worship

- Nanzenji Temple 南禅寺, Chōshō-in Sub Temple 聴松院 (Kyoto). Temple Web Site | Photos.

- Shōtaku-in 聖沢院 (Kyoto). Possesses a polychrome painting of Marishiten said to be of Korean provenance; designated an Important Cultural Property. Artwork Citation.

LEARN MORE

References for deities discussed above are found underneath each deity entry. Below are other helpful resources.

- Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙, “Collected Illustrations of Buddhist Images.” Published 1690 (Genroku 元禄 3). Major Japanese dictionary of Buddhist iconography. Hundreds of pages & drawings, with deities classified into approximately 80 categories. Above line art from the expanded Meiji-period (1868-1912) reprint of the standard 1783 edition. Purchase Meiji-period reprint here (J-site).

- JAANUS. Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. A wonderful online dictionary compiled by the late Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent. It covers both Buddhist and Shinto deities in great detail. Over 8,000 entries. Written in English, yet presenting all key terms in Japanese.

- A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms. With Sanskrit & English Equivalents. Plus Sanskrit-Pali Index. By William Edward Soothill & Lewis Hodous. Hardcover, 530 pages. Published by Munshirm Manoharlal. Reprinted March 31, 2005. ISBN 8121511453.

- Buddhism (Flammarion Iconographic Guides)

, by Louis Frederic, Printed in France, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. A highly illustrated volume, with special significance to those studying Japanese Buddhist iconography. Includes many of the myths and legends of mainland Asia as well, but its special strength is in its coverage of the Japanese tradition. Hundreds of accompanying images, both B&W and color. , by Louis Frederic, Printed in France, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. A highly illustrated volume, with special significance to those studying Japanese Buddhist iconography. Includes many of the myths and legends of mainland Asia as well, but its special strength is in its coverage of the Japanese tradition. Hundreds of accompanying images, both B&W and color.

- Tobifudo Deity Dictionary. Ryūkozan Shōbō-in Temple 龍光山正寶院 (Tokyo). Tendai Sect. This site has given me permission to use its Sanskrit Seed images and esoteric mantras.

- Hindu Gods and Goddesses in Japan. Saroj Kumar Chaudhuri, Vedams, 2003, xviii, 184 p, ills, ISBN : 81-7936-009-1. See partial preview of book at Google Online Book Preview.

- Kitchen Gods in Japan (this site)

- Fukudoku-ten 福徳天, Fukutoku-shin 福徳神. Tenbu who bring good fortune and luck.

Please visit this J-Site to see photos of various TEN (Deva) who bring good fortune.

THIS IS A SIDE PAGE

RETURN TO MAIN TENBU (DEVA) PAGE

|

|

|