|

|

|

|

|

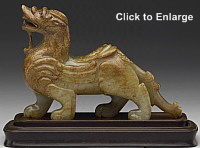

Bìxié 避邪 or 辟邪 (lit. “to ward off evil”)

Another name for the Pìxiū (Pi Hsieh)

Green Jade (browned with age), H = 9.3 cm

Han Dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD)

National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan

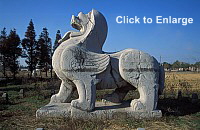

Stone, 300 cm X 311 cm.

Double-horned, in front of the Yongningling Mausoleum in Nanjing, China.

Southern Dynasties Period (420-589).

Photo courtesy this C-site.

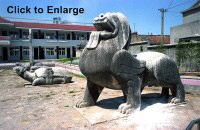

Stone, in front of tomb of Xiao Hong

Nanjing, China.

Southern Dynasties Period (420-589).

Photo courtesy this C-site.

Stone, in front of tomb of Xiao Hong

Nanjing, China.

Southern Dynasties Period (420-589).

Photo courtesy this C-site.

|

|

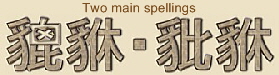

JP = Hikyū 貔貅, CHN = Pìxiū 貔貅

Also known in Chinese as Bìxié 避邪 or Tiān Lù 天禄

Also known in Japanese as Hekija 辟邪 or Tenroku 天禄

貔 = leophoric beast, male (leopard, panther)

貅 = brave, fierce, courageous, female

豼 = heraldic beast symbolizing bravery

辟邪 = valiant soldier, wards off evil

Origin = China, but probably transmitted

to China via Western Asia or Persia

A composite beast of ancient origin, mostly forgotten in Japan, but still popular today in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore. The mythological dragon-headed, lion-bodied Pìxiū 貔貅 (also spelled 豼貅) were traditionally depicted in China as a male-female pair, one with a single horn (male, Pì 貔) and the other with two horns (female, Xiū 貅), but in modern times they each commonly appear with only one horn. In ancient China, statues of the two guarded the entrance to the tomb, as they are thought to ward off evil and protect wealth. In old China, the beasts were also commonly portrayed with hoofs, wings, and tails, and supposedly appeared on the banners of the emperor’s chariots (兵車に立てた旗). In Japan, the Hikyū are largely ignored, having been supplanted by the Koma-inu (magical lion dogs) and Shishi (magical lions), who traditionally stand guard outside the gates of Japanese Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. In Japan, effigies of Shishi lions are also commonly used as architectural elements, placed under the eaves of both Shintō shrines and Buddhist temples to ward off evil spirits. Let us recall that, in China, the Pìxiū also serve this role, and in olden times were commonly displayed on the roof corners of the homes of the emperor and gentry.

The Hikyū are leophoric & magical beasts who appeared as early as the 4th-century BC as winged lion hybrids on the tomb of China’s King Cuò  of Zhōngshān 中山. <See Wolfgang Behr of Zhōngshān 中山. <See Wolfgang Behr

References: Source: Scholar Wolfgang Behr

International Journal of Asian Studies, Volume 9, 2004. Story by Wolfgang Behr, Hinc sunt leones - two ancient Eurasian migratory terms in Chinese revisited. On page five, he writes: "the lion (re-)appears as a gryphon or winged leophoric chimera in the tomb of King Cuo of Zhongshan during the fourth century B.C., and a western Shanxi site from the first century B.C. See story here. >

Says the National Palace Museum (Taipei, Taiwan): “In China during the Han dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD), the pi-hsieh (aka Bìxié) were commonly represented as winged, four-legged beasts, a form that was probably transmitted from Western Asia. Often found as huge stone statues, they would be placed along the spirit road leading up to tombs. Some were also carved from quality jade and used as ornaments for the wealthy and powerful.” <end quote>

In modern times, the mythological Hikyū (Píxiū) remain important to practitioners of Fusui 風水 (Chn. = fēngshuǐ ; geomancy) and to gamblers in many Asian nations. Gamblers in China and Taiwan, for example, commonly keep miniature statues of the creatures in their gambling parlors -- the pair is said to represent fair and honest play. Such modern-day beliefs originated in earlier Chinese folklore. In one legend, the male beast (called Tiān Lù 天禄 in China) somehow angered the Jade Emperor, who punished it by limiting its diet to gold and by sealing its rectum -- thereby preventing the animal from defecating. The Tiān Lù thus came to represent the acquisition and preservation of riches. Indeed, in contemporary artwork, the beast is sometimes depicted holding gold (or coins) in its mouth, or shown together with a bat (Biānfú 蝙蝠; Jp. = Henpuku), the symbol of wealth, long life, and other blessings in China. See photos below for examples.

Pìxiū Naming Conventions

- Pìxiū 貔貅. Chinese. Refers to the male-female pair. Like the mythological Phoenix (a male-female pair known as Fèng Huáng 鳳凰) and the Qílín 麒麟 (a male-female pair of giraffe-like mythological beasts), the term Pí 貔 refers to the male of the species and Xiū 貅 refers to the female. In Japan, Pìxiū is read as Hikyū.

- Tiān Lù 天禄. Chinese. The single-horned beast. Male. 天禄 literally means heavenly wealth or celestial blessings or heavenly salary. Tiān Lù is said to have angered the Chinese emperor, who then sealed the beast’s anus and restricted the beast’s diet to gold. Hence Tiān Lù is associated with acquiring and keeping wealth. In Japan, Tiān Lù is read as Tenroku 天禄.

- Bìxié 避邪 or 辟邪. Chinese. The double-horned beast. Female. Literally “ward off evil (邪悪を避ける).” In Japan, it is read Hekija 辟邪, as in the Exorcists Scroll (aka Hekija-e 辟邪絵). The term Hekija is also used figuratively in Japan to mean “valiant soldier.”

- Says scholar Wolfgang Behr (page 6)

References: Source: Scholar Wolfgang Behr

International Journal of Asian Studies, Volume 9, 2004. Story by Wolfgang Behr, Hinc sunt leones - two ancient Eurasian migratory terms in Chinese revisited. On page five, he writes: "the lion (re-)appears as a gryphon or winged leophoric chimera in the tomb of King Cuo of Zhongshan during the fourth century B.C., and a western Shanxi site from the first century B.C. See story here. : “Winged leophoric creatures, usually described as bìxié 辟邪 (guardians against evil influences, heresies) by modern archaeologists, with reference to glosses in ancient Chinese texts and to the many monumental bìxié stone sculptures erected since the renaissance of the motif in the Eastern Han period. For an overview of pertinent finds and an art historical appreciation see Sū Jiàn (1995).” On page 14, Behr says: "Let us first take a closer look at shīzǐ 師子, the Chinese word for lion, which eventually survived into the modern Chinese language. But shīzĭ is not the only ancient term for 'lion' we have in Chinese. In fact, there are at least five other 'leophoric' names mentioned in early Chinese texts: 狻, 尊, 酋, 騶, 騶.” <end quotes>

Modern metal statues sold in Japan but made in China. H = 15 cm. Photo from A to Z Dictionary.

Modern metal statues sold in Japan but made in China. H = 15 cm. Photo from A to Z Dictionary.

Modern metal statue sold in Japan but made in China. H = 15 cm. Photo from A to Z Dictionary.

Below Text Courtesy of mingjade.com/the-legend-of-pixiu/ (last accessed Feb. 2011)

The Pixiu is also known as Tianlu 天禄 (Heavenly Salary) and Bixie 辟邪 (Wards off Evil). It is a magical beast in ancient Chinese mythology with a dragon's head, a horse's body, a qilin's feet, and the overall shape of a lion. Its fur is greyish-white, and it can fly. The Pixiu is fierce and a good fighter, and likes sucking the blood or essence of demons and converting it into wealth. It is tasked with patrolling the heavens and stopping demons and diseases from causing chaos. One version of the legend identifies the Pixiu as the 9th son of the Dragon. In ancient times, the Pixiu was also used as a synonym for an army (because of its ferocity). One legend says that the Pixiu broke one of the rules of Heaven, and was punished by the Jade Emperor, who restricted its food to the wealth of the world. It could swallow wealth without ever having to defecate. This ability to gain wealth without letting it out was auspicious enough for many Chinese to use jade carvings of the Pixiu as ornaments even today.

Below Text Courtesy cozychinese.com/pixiu/ (last accessed Feb. 2011)

By William C. Hu and David Lei. Měng Shòu (Mengshou) 猛獸, literally fierce beast. It is mentioned in the Shí Zhōu Jì 十洲記 (Record of the Ten Continents), a 1st-or-2nd century BC text included in the early 5th-century Taoist compilation Dàozàng 道藏 (Daoist Canon, Taoist texts collected around 400 AD). It is a symbol that brings good fortune so that gamblers usually have a pair prominently displayed in the gambling parlors and dens, with the two statues representing fair play and no fear of any cheating, Pixiuzuozhen 貔貅坐鎮 (pí xiū zuò zhèn). Also, small images in unglazed pottery are carried by gamblers for good luck. In addition, there is also a dance, which is similar to the Lion Dance called Wupixiu 舞貔貅 (wǔ pí xiū).

Below Text Courtesy of chinahistoryforum.com/index.php?/topic/7619/ (last accessed Feb. 2011)

The appearance of Píxiū was mentioned in the Book of Han 汉书 on the section of Accounts of the Western Regions 西域传. In the country of Wū Gē Shān Lí there exists a creature called táo bá 桃拔, lion 狮子 and rhinoceros (the character should be 犀牛, not 尿牛.) An annotation made in the Mèng Kāng indicates táo bá to be a creature like deer with a long tail, those with one-horn called tiān lù, those with two horns called bìxié, thus equating the creature to píxiū. The description of its appearance evolved through the dynasties until it settled on short wings, two horns, coiling tail, with manes connected to either the chest or the spine, protruding eyes and long menacing fangs. Many depictions of the creature today give it a single horn and a long tail.

Below Text Courtesy of chineseliondancers.webs.com/Tian_Lu.htm (last accessed Feb. 2011)

The appearance of Pi Xiu was mentioned in the Book of Han (汉书) on the section of Accounts of the Western Regions (西域传). In the country of Wū Gē Shān Lí there exists a creature called táo bá (桃拔). An annotation made by by Mèng Kāng indicated táo bá to be a creature like deer with a long tail, those with one-horn called tiān lù, those with two horns called bìxié, thus equating the creature to pí xiū. The discriptions of pi xiu have varied throughout the ages possibly because people have intermixed tian lu and bi xie together. Besides the horns, the pixiu is described both with and without wings. Also Bi Xie was female and in charge of warding off evil while Tian Lu is said to be male and in charge of wealth. As the story goes, the myth of Tian Lu tells that the creature violated a law of heaven, so the Jade Emperor punished it by restricting Tian Lu’s diet to gold, and prevented the creature from defecating by sealing its rectum. Thus, Tian Lu can only absorb gold, but cannot expel it, thus the origin of Pi Xiu's (Tian Lu) status as a symbol of the acquisition and preservation of wealth and why it is always seen as holding gold in its mouth.

LEARN MORE

- Behr, Wolfgang, International Journal of Asian Studies, Volume 9, 2004. Hinc sunt leones - two ancient Eurasian migratory terms in Chinese revisited. On page five, he writes: "the lion (re-)appears as a gryphon or winged leophoric chimera in the tomb of King Cuo of Zhongshan during the fourth century B.C.

- Chinese Animal Symbolism and Feng Shui Online Dictionary

- Chinese Creatures and Feng Shui (J-site)

- Chinese-English Dictionary Online Pìxiū Entry

- Howard, Angela Falco, Chinese Sculpture, pp. 163-169

- J-store #1 selling statues online of the beasts

- J-store #2 selling statues online of the beasts

- Pìxiū Entry at Wikipedia (J-site)

- Photo Tour of the Pìxiū in and around Nanjing (Chinese site). Stone tomb figures from the Southern Dynasties (420-589) have been found at thirty-one sites in and around Nanjing

- Sankai Ibutsu 山海異物 (Mythical Creatures of the Mountains and Seas, two volumes). The Sankai Ibutsu is an early 17th-century illustrated Japanese book now in the Spencer Collection of the New York Public Library. See article by Masako Nakagawa (Villanova University) in Sino-Japanese Studies, Volume 11, pages 33-34, wherein she provides a description of 47 Chinese creatures gleaned from the Sankai Ibutsu, from the Wang Ch'i 王圻, San-ts'ai t'u-hui 三才圖會 (dated 1609/10, 3 vols. Shanghai: Hsinhua shu-tien, 1988), and from John A. Goodall's Heaven and Earth: 120 Album Leaves from a Ming Encyclopedia: San-ts'ai t'u-hui, 1610 (London: Lund Humphries, 1979). This document, however, does not include any reference to the Pìxiū, but is offered here as a sampling of the many strange creatures in Chinese mythology.

- Till, Barry (1980), Some Observations on Stone Winged Chimeras at Ancient Chinese Tomb Sites, Artibus Asiae 42 (4): 261–281.

First published = Feb. 27, 2011

|

|