|

|

|

|

GORINTŌ / GORINTO / GORINTOU / 五輪等

FIVE-TIER PAGODA, FIVE-ELEMENT STUPA

FIVE-WHEELED RELIQUARY, FIVE-LAYERED STELE

Funerary Monuments, Often Containing Relics of the Buddha

Reliquaries & Memorials, Often Containing Relics of the Buddha

Funeral Urns, Gravestones, Buddhist Votive Objects

Three-Element Stele, Hōkyōinto Stupas, Sekidō, Kasatōba

See Ishidōrō for Stone Lanterns

See Dōsojin for Protective Stone Markers

See Stones Top Menu for overview of all categories

Funerary Urns for Priest Meiken and Others

Excavated at Saihoji Site. Nanbokucho Era, 1336 - 1392 AD

Photo taken at Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Museum in Kamakura

|

NOTE: This page relies heavily on the wonderful research of the Japanese Architecture & Art Net User System (JAANUS). A visit to their online dictionary is highly recommended. Much of their research on stone lanterns is reproduced below, with their permission. Thank you JAANUS. I would also like to thank Dr. Gabi Greve, a longtime Japan resident, for her assistance, research, and advise. This page is also accompanied by a Photo Tour of various gravestone styles. NOTE: This page relies heavily on the wonderful research of the Japanese Architecture & Art Net User System (JAANUS). A visit to their online dictionary is highly recommended. Much of their research on stone lanterns is reproduced below, with their permission. Thank you JAANUS. I would also like to thank Dr. Gabi Greve, a longtime Japan resident, for her assistance, research, and advise. This page is also accompanied by a Photo Tour of various gravestone styles.

|

|

INTRODUCTION. Gorintō (Gorinto) 五輪塔 literally means five-ring or five-wheel pagoda. Also called Gorin 五輪, Gorinsekitō 五輪石塔, Hōkaitō 法界塔, Gorintōba 五輪塔婆, or Gogedatsurin 五解脱輪. There are many English translations of gorintō, including five-tier tomb, five-element stele, five-wheel pagoda, five-ring tower or five-tier grave marker. Whatever you may call, it is made of five pieces of stone and serves as a grave marker or cenotaph erected for the repose of the departed, one that in olden days contained a relic of the Buddha (hair, fingernail, bone, etc.) Although many older examples are found in Kyoto and Nara, those made during the Kamakura Period are the most beautiful, say experts on Gorintō. The height ranges from one to four meters. Considered indigenous to Japan and not found in other countries. Most of the existing Gorintō in Kamakura were made in the late Kamakura Period.

Says JAANUS: Each piece in the five-story pagoda (Sanskrit = stupa) corresponds to one of five elements. The bottom story is square and corresponds to the earth ring (Japanese = Chirin 地輪). Next is the spherical water ring (Japanese = Suirin 水輪), surmounted by the triangular ring of fire (Japanese = Karin 火輪). Above this is a reclining half-moon shape (Japanese = Fūrin 風輪), representing the wind, and topmost is the gem-shaped ring of space (Japanese = Kūrin 空輪).

It is believed that the Gorintō was first adopted in the mid-Heian period by the Esoteric Buddhist sects of Shingon 真言 and Tendai 天台. In Shingon Buddhism it embodies Dainichi Nyorai, the cosmic Buddha. Dainichi is the main deity of reverence among Shingon adherents, and the topmost piece of the five-element pagoda -- the space ring -- corresponds to Dainichi (see below diagram). The Gorintō also symbolized the Buddha and his teachings, the five directions of space (four cardinal directions and the zenith), the five major episodes in the life of the Historical Buddha, the five Buddha of the current cycle (Skt. = Kalpa), the five elements, and a host of other groupings of five objects or ideas. Each story of the pagoda is usually inscribed with the Sanskrit character for the element represented. After the Heian period, Gorintō were often used as funerary monuments or reliquaries. Most Gorintō are two to three meters high; the tallest example, at Iwashimizu Hachimangū 岩清水八幡, is six meters high. Large examples are made of stone (Gorinsekitō 五輪石塔), while smaller ones are sometimes made from wood (Itagorintōba 板五輪塔婆), or clay (Nendogorintōba 粘土五輪塔婆), or metal (Kandōrō 金灯篭).

These smaller stupas are used as votive offerings, and are often hand crafted by those who present them to the temple. The oldest known is the Chūsonji Gorintō at Chūsonji Temple, dated 1169. It can be seen at Chūsonji Shakuson-in 中尊寺釈尊院 in Iwate Prefecture. Sometimes parts of a Gorintō are used for decoration in a garden, and the spherical “water ring” and the trapezoidal ”fire ring” sometimes serve as a handwash basin (Chōuzubachi 手水鉢). An example of this type can be seen at Katsura Rikyū 桂離宮 in Kyoto (Momoyama Period, 1568-1615). Sometimes a small-scale Gorintō made from a single block of stone (Issekikokusei Gorintō 一石刻成五輪塔) is also used in private gardens. <end quote from JAANUS>

Above chart adapted from Ishidan J-Site.

NOTES ON ABOVE CHART. Below text courtesy JAANUS.

- Chirin 地輪. Literally “earth ring,” and the base piece of the lantern. Also called Dairin 台輪. It is often shaped like a cube with a lotus flower bottom. In this may be carved a hole for holding water for hand washing (example Raigōji 来迎寺).

- Suirin 水輪. Literally “water ring,” the spherical second story of the five-story pagoda. The suirin of a five-story stone pagoda (gorin sekitō 五輪石塔) may also be used as a water basin (mitatemono chōzubachi 見立物手水鉢), specifically for teppatsugata chōzubachi 鉄鉢形手水鉢.

- 月輪 -- Gachirin, the Moon or Moon Disc

Also called Gatsurin or Getsurin. A perfectly round circle meant to represent the full moon, a frequently used symbol in Buddhist painting and sculpture. It represents the Buddha’s knowledge and virtue which are considered perfect and all-encompassing. It also symbolizes the aspirations of sentient beings to attain Buddhahood. In the Kongōkai Mandara 金剛界曼荼羅 of Esoteric Buddhism, for example, each of the nine divinities is shown seated in the circle of a full moon. The Gachirin is also the chief attribute of Gakkō (Gekkō) Bosatsu, who is often shown in statues and paintings wearing a headpiece representing the moon or holding a circular form in the palm of his hand. <end JAANUS quote>

|

Deities of the Five Elements

GROUP ONE -- Esoteric Buddhism

|

|

|

SANSKRIT

Vairocana

Space/Center/Zenith

Akshobhya

Air / Wind / East

Ratnasambhava

Fire / South

Amitabha

Water / West

Amoghasiddhi

Earth / North

|

JAPANESE

Dainichi Nyorai 大日

Space/Center/Zenith

Ashuku Nyorai 阿閦如来

Air / Wind / East

Hōshō Nyorai 宝生

Fire / South

Amida Nyorai 阿弥陀

Water / West

Fukūjōju Nyorai 不空成就

Earth / North

|

|

NOTES ON GROUP ONE

- These Five Buddhas are known as the Five Jina, or the Five Tathagata, or the Godai Nyorai, a grouping especially important to the Shingon Sect. In artwork, the five appear most frequently on the mandalas of Japan’s Esoteric Buddhist sects. In ancient India, stupas were thought to be derived from funerary tumuli and only later to have become commemorative monuments specific to Buddhism, yet it appears that the images of the Jinas were only added late to the directional sides of stupas. For esoteric sects, these Five Jinas represent the essential symbols of the Law (Dharma), and were subsequently identified with all the groups of five objects or ideas, such as the five historical Buddhas, the five senses, the five aggregates, the five cardinal points, the five virtues, the five sins, etc. <source Flammarion Iconographic Guide, p. 125> .

- FIVE ELEMENTS, CHINA. In China, the theory of five elements (or energies) began with a different set of concepts. Called wu hsing (五行) in Chinese, the theory’s first celebrated exponent was Tsou Yen (350 - 270 BC). The five energies were symbolized as (1) wood, which as fuel gives rise to (2) fire, which creates ash and gives rise to (3) earth, which in its mines contains (4) metal, which (as on the surface of a metal mirror) attracts dew and so gives rise to (5) water, and this in turn nourishes (1) wood. This is called hsiang sheng (相生), or the “mutually arising” order of the forces. These forces were also arranged in the order of “mutual conquest” (相勝) -- likewise read hsiang sheng, but sheng is a different ideogram -- in which (1) wood, in the form of a plow, overcomes (2) earth, which, by damming and constraint, conquers (3) water which, by quenching, overcomes (4) fire which, by melting, liquifies (5) metal, which, in turn, cuts (1) wood. <quoted from “TAO, The Watercourse Way” by Alan Watts>

- The five elements also correspond to the five parts of the body: hips (yellow), navel (white), heart (red), between the eyebrows (dark, black, or blue), and the top of the skull (bright). <source Flammarion Iconographic Guide, p. 311).

|

|

|

Deities of the Four Elements

GROUP TWO -- Esoteric Buddhism

Their Sanskrit seeds sometimes appear on the four directional sides of the stele.

|

|

|

SHINTŌ

風神 Fūjin

God of Wind

火神 Kajin

God of Fire

水神 Suijin

God of Water

地神 Chijin

God of Earth

|

BUDDHIST

風天 Fūten

God of Wind

火天 Katen

God of Fire

水天 Suiten

God of Water

地天 Chiten

God of Earth

|

|

These four are known as the Shishū Kongō 四執金剛, literally “Four Vajra Rulers of the Four Elements,” which are earth, water, fire, wind. Also known as the Four Diamond Protectors. They are mentioned in the Dainichi-kyō Sutra 大日經 as gods of the SE, SW, NW, NE. The Japanese version does not fully conform to the Dainichi-kyō Sutra.

|

|

|

Gilt bronze Hōkyōintō three-tier stele, discovered in excavations at Oku no In (奥之院; near Kōyasan Monestary; see Ishidōrō page) during the late Meiji Era. The Sanskrit seed words for each of the Four Diamond Protectors (of the Kongōkai Mandala, or Diamond World Mandala; see NOTES below) are engraved on the four directional sides of the stele. The foundation stone is engraved with a memorial message that is dated 1287 AD.

|

|

NOTES ON GROUP TWO. In the Diamond World Mandala (Kongōkai Mandala 金剛界曼荼羅) of Shingon Buddhism, one finds mention of Four Diamond Protectors 四執金剛. These four are also known as the Four Great Shintō Gods (Shi no Ōkami 四大神). According to Dr. Gabi Greve, each of the four has a female counterpart, a sort of heavenly princess (KI, 妃). The JIN reading signifies a deity of Japanese origin and Shintō associations, while the TEN reading refers to deities of Indian origin and Buddhist associations. The term TEN is translated in English as DEVA, and the above four deities are members of the 12 Deva Guardians of Buddhist tradition. In a purely Japanese context, the Shintō (JIN) names may also be read in a third different way. For example, Suijin may be read as Mizu no Kamisama 水の神様, and Kajin may be read as Hi no Kamisama 火の神様.

|

|

|

Gravestones at Koyasan.

Photo by Dr. Gavi Greve

Along the approach to Kōbō Daishi's mausoleum at Kōyasan 高野山 are some thousands of tombstones, including those of historically important figures, such as Oda Nobunaga and Takeda Shingen, both feudal warlords from the Sengoku Period (1467-1568). The tallest tombstone is 10 meters high, and marks the grave built for the wife of Tokugawa Hidetada (1579-1632), the second Tokugawa shogun. See Ishidoro page for more on Koyasan (Kongobuji).

|

|

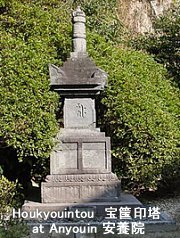

HŌKYŌ-INTŌ (Hokyointo, Hokyo-into) 宝篋印塔 HŌKYŌ-INTŌ (Hokyointo, Hokyo-into) 宝篋印塔

Three-Element Stele. Text Courtesy Tadahiro Kondo. If Gorintō translates as five-element stele, then Hōkyō-intō should be called a three-element stele, representing, from the bottom, the earth, water and fire. In the middle is a square cube, and on each surface, an image of the Buddha is often engraved. Like Gorintō, this was erected mostly as a cenotaph and partly as a tomb. Generally, all stones of the Hōkyō-intō are squarely cut and the overall structure consists of the footing, body, umbrella and ornamental top. An-yō-in Temple has the oldest one in the Kanto area behind its main hall. <end quote by Tadahiro Kondo>

HŌKYŌ-INTŌ

Three-Tier Stupa (Text courtesy JAANUS)

A type of pagoda (Skt. = Stupa) originally made as a repository for copies of the Hōkyō-in Darani Sutra 宝筺印陀羅尼. In the Heian period hōkyōintō (hokyointo) were made of gilt bronze or wood, but by the Kamakura period these pagodas were usually made of stone and used as funerary markers. The distinctive rectangular shape of the hōkyōintō has a low, rectangular foundation, kiso 基礎, surmounted by a square body, tōshin 塔身, which often bears an image of the Buddha or a Sanskrit syllable.

The top story or “umbrella” (kasa 笠) is a stepped pyramid with wing-like decoration at the four corners. Above this an inverted bowl shape (fukubachi 伏鉢) supports a ring of lotus petals (ukebana 請花). Nine rings (kurin 九輪) form the shaft (sōrin 相輪), which supports another lotus petal ring and finally, a jewel-shaped form called a hōju 宝珠 sits atop the structure. The parts from the fukubachi to the hōju are all circular, the other members of the hōkyōintō are square. The podium itself is sometimes decorated with a foliated form (kōzama 格狭間) that resembles a side view of a molding, while the lower half resembles the outline of a bowl. The body of the pagoda has either carvings of the Buddha on each side or Sanskrit letters. However, undecorated pagoda bodies also exist, and the stepped coping may have moldings carved on the undersides. Examples: 1259 AD, Nara Arisatochō 有里町; Enfukuji Hōkyōintō 円福寺宝篋印塔, Linji Hōkyōintō 為因寺宝篋印塔 1265, Kyoto, 1293 Nara. <end quote JAANUS>

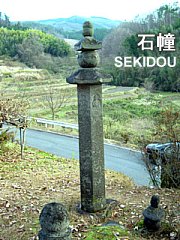

Sekidō (Sekido) 石幢

Literally “stone flag.” A type of stone pagoda with a hexagonal or octagonal base, a banner-shaped shaft (dōshin 幢身), a niche, a coping stone shaped like a roof and one or more onion-shaped decorative jewels (hōju 宝珠) on top. Some sekidō have no base so that section is inserted directly into the ground. Sanskrit letters and/or Buddhist images are carved on each side of the shaft. Some sekidō have octagonal or hexagonal shafts. Many have only a shaft and roof. Sometimes they resemble stone lanterns without a light box. According to some scholars, sekidō probably evolved from kasatōba 笠塔婆 (see entry below). The oldest extant date from the Kamakura period (1185-1333), but many were made in the late 14th century and after. <Source: JAANUS> Literally “stone flag.” A type of stone pagoda with a hexagonal or octagonal base, a banner-shaped shaft (dōshin 幢身), a niche, a coping stone shaped like a roof and one or more onion-shaped decorative jewels (hōju 宝珠) on top. Some sekidō have no base so that section is inserted directly into the ground. Sanskrit letters and/or Buddhist images are carved on each side of the shaft. Some sekidō have octagonal or hexagonal shafts. Many have only a shaft and roof. Sometimes they resemble stone lanterns without a light box. According to some scholars, sekidō probably evolved from kasatōba 笠塔婆 (see entry below). The oldest extant date from the Kamakura period (1185-1333), but many were made in the late 14th century and after. <Source: JAANUS>

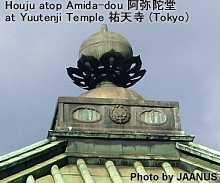

Hōju (Hoju) 宝珠

Also pronounced hōshu. A sacred gem. Usually a ball or tear-drop shape object that is sacred to Buddhism. It is believed to have the power to expel evil, cleanse corruption, and fulfill wishes. (Related term is nyoihōju 如意宝珠.) The term giboshi or gibōshu (擬宝珠) is often used to refer to the hōju shape reproduced as an architectural decoration. This shape is used on the top of a pagoda (sōrin 相輪), on the top of a pyramidal roof (hōgyōzukuri 方形造) of a Buddhist hall (endō 円堂), on a stone lantern (ishidōrō 石灯籠), or on the sculptured head of railing pillars. Houju-shaped pillar heads are called hōjugashira (宝珠頭); pillars topped with a hōju are called hōjubashira 宝珠柱 or giboshibashira 擬宝珠柱; and railings with this type of pillar are called giboshikōran 擬宝珠勾欄. The hōju on pagodas and Buddhist halls are usually made of bronze and often decorated with flame designs. The hōju with flames rising from it is called kaenhōju 火炎宝珠. When used as a decoration for a lantern, the tip of the ball may be sharply pointed or gently rounded depending on the date of the lantern's production, and may be supported by a lotus-petal form (ukebana 請花). Generally, the earlier hōju have more gentle points and are rounder in form. The tip becomes more sharply pointed and the form more square-shaped in the Momoyama period (last quarter of the 16th century). A hōju with a lotus petal base is found as an attribute (jimotsu 持物) of Buddhist figures such as Jizō Bosatsu and Kokūzō Bosatsu and Kichijōten, as seen on the 9th-century Jizō Bosatsu at Kōryūji Temple 広隆寺 in Kyoto. <Source: JAANUS>

Kasatōba 笠塔婆

Also called kasasotōba 笠卒都婆. A memorial or grave stone. The most common has a square shaft (tōshin 塔身) placed on a roughly hewed base stone. A pyramidal-like coping stone (kasa 笠) at the top suggests a roof. On top of the coping or between the coping and top ornament is an jewel shape (hōju 宝珠) or bowl shape. Example: Ryūmonji 竜門寺 1335, in Nara. Inscriptions in Sanskrit letters may be carved into the shaft, or Buddhist dieties may be rendered in low relief on the upper part. The upper part is called butsugan kasatōba 仏龕笠塔婆 and may have solid stone wheels set vertically within the shaft so that the devout can turn the stone while reciting invocatory prayers. An example of this type is found at Akagi Jinja 赤城神社, 1490, in Gunma Prefecture. It has Six Jizō (Roku Jizō 六地蔵) figures carved into it. <Source: JAANUS>

|

GLOSSARY OF KEY WORDS

Not inclusive. See above text for more words and definitions.

|

|

Japanese

|

Hiragana

|

English

|

|

五輪塔

|

ごりんとう

|

Gorintō (Five-Tier Pagoda or Stupa). See above for details.

|

|

笠塔婆

|

かさとうば

|

Kasatōba (Memorial or Grave Stone). See above for details.

|

|

石幢

|

せきどう

|

Sekidō (Stone Flag). See above for details and image.

|

|

宝篋印塔

|

ほうきょう いんとう

|

Hōkyō-intō (Three-Tier Pagoda). See above for details.

|

|

燈燭

|

とうしょく

|

Tōshoku (Funeral Lanterns)

|

|

見立物手水鉢

Description

courtesy JAANUS

|

みたてものちょうずばち

|

Mitatemono Chōzubachi. Literally “re-used-object” water basins. A type of water basin (chōzubachi 手水鉢) made from a stone which previously had served a different function. Typically parts from old stone pagodas (sekitō 石塔), temple foundation stones (garanseki 伽藍石) or stone bridges are used. Also called riyōmono chōzubachi 利用物手水鉢 or "functional object water basins," they are used for both tsukubai 蹲踞 and hachimae-no-ishigumi 鉢前の石組. Common mitatemono chōzubachi types include the kesagata 袈裟形 or "surplice shape" which uses the central part of a treasure pagoda (hōtō 宝塔); water basins like wakutamagata 湧玉形 made from a section of a five-ring pagoda; the umegae 梅が枝 or "plum branch" from the lid of an old tomb; the kasagata 笠形 or "umbrella shape" made from the stone of a stone pagoda, and the shihōbutsu 四方仏. Mitatemono chōzubachi are contrasted with natural stone water basins, shizenseki chōzubachi 自然石手水鉢.

|

|

塔身

Description

courtesy JAANUS

|

とうしん

|

Toushin. The framework of a pagoda (tō 塔), excluding the roof (yane 屋根) and eaves (noki 軒). The term also applies to the body of stone pagodas, excluding the roof and base.

|

|

石幢形石灯籠

Description

courtesy JAANUS

|

せきどうがたいしどうろう

|

Sekidougata Ishidourou. A type of stone lantern (ishidōrō 石灯籠). Shaped like a Buddhist memorial (sekidō 石幢), it has a hexagonal or octagonal base with a faceted pillar on it. On top of the pillar is the fire box, topped with canopy and sacred jewel, common to most stone lanterns. The special characteristic of the sekidougata ishidourou are the Six Buddhas carved in relief on each face of the fire box. Originally derived from the sekidō, a monument displaying Buddhist relief carvings, it is thought that the fire hole was carved out to adapt the monument to function as a lantern.

|

|

Five-Tier Pagoda at Kofukuji Temple in Nara

Photo by Bernhard Scheid. See Bernhard’s Pagoda Photo Tour Here

Pagoda Chart. From Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, 1983

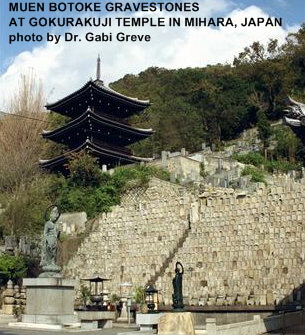

MUEN BOTOKE 無縁仏

People who die leaving no one to attend to their grave; a spirit with no link (縁, en) to the living; wandering spirits; the unknown dead; forgotten souls. Some Japanese fear a time will come when no one will be left to attend to the family grave or remember to honor the departed family member with visits and gifts. In Japanese terms, this is the fear of becoming a muen botoke (a spirit with no link to the living; a dead person without living relatives). In order to dispel the fear of becoming a muen botoke, some living Japanese people go to Isshin Temple in Osaka (Pure Land tradition). This temple still practices the little-known kotsubotoke method -- the practice of pulverizing the cremated bones of departed humans and using the bone powder to construct Buddhist images. Some people are attracted to this idea, and at Isshin Temple, they “will” their bones for this purpose.

LEARN MORE

- Photo Tour of Gorintō (this site)

- Dōsojin (Protective Stone Markers; this site)

- Magaibutsu (Buddhist Images Carved on Cliffs; this site)

- Sekibutsu (Free-standing Buddhist Images Carved in Stone; this site)

- Ishidoro, Japanese Stone Lanterns (this site)

- JAANUS. Outside site. Japanese Architecture & Art Net User System. Highly recommended.

- Japanese-language links to Dōsojin Stone Markers. Numerous nationwide photo tours.

- Buddhism: Flammarion Iconographic Guides, by Louis Frederic, Printed in France, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. A highly illustrated volume, with special significance to those studying Japanese Buddhist iconography. Includes many of the myths and legends of mainland Asia as well, but its special strength is in its coverage of the Japanese tradition. Hundreds of accompanying images/photos, both B&W and color. A useful addition to your research bookshelf.

- Jewel in the Ashes: Buddha Relics and Power in Early Medieval Japan. . By Brian D. Ruppert. Harvard University Asia Center (July 1, 2000). ISBN-10: 0674002458. Focused on relic worship in medieval Japan. Copious reference notes, this work is aimed at scholars. It includes a very useful glossary of terms. Highly recommended.

- Photo Galleries (Outside Sites)

KOYASAN, 高野山, KONGOBUJI TEMPLE

Stone gravestones and lanterns at Koyasan

http://inoues.net/club/okunoin.html

Takes a while to load, but the many photos give you a good impression of the walk in the woods along the path to the Hall of Lanterns and Oku no In at Koyasan Monestary.

GETTING HOLY IN WAKAYAMA

Japan Times Story (Dec. 10, 2004) by Mariko Yasumoto

www.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/getarticle.pl5?fv20041210a1.htm

ū ā ō Ō

|

|