|

|

|

|

Last Update: July 2014 -- Added photo and notes Last Update: July 2014 -- Added photo and notes

Twenty-Eight Constellations

28 Moon Lodges, 28 Lunar Mansions

28 Deities in Shingon & Tendai Mandalas

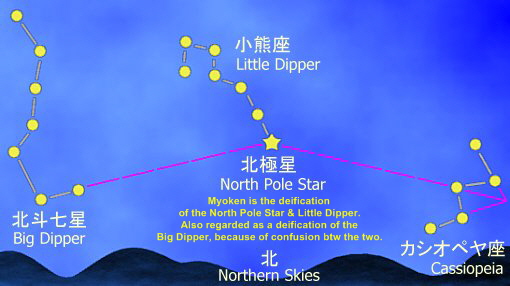

Also Big Dipper Stars & Pole Star (Myōken Bosatsu)

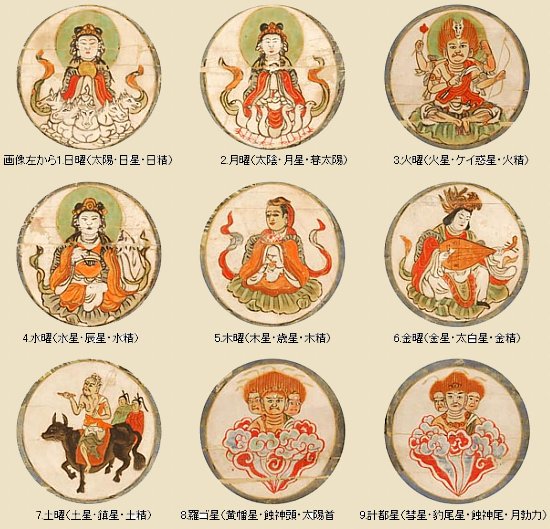

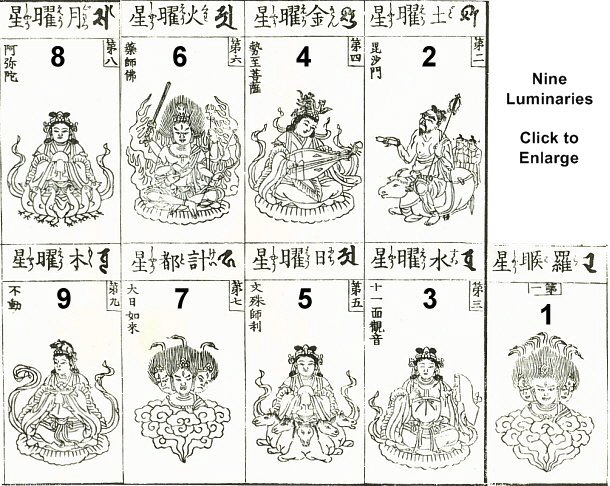

Also Five Planets, Sun, Moon, Nine Luminaries

Jp. = 二十八宿 = Nijūhasshuku

Chn. = 二十八宿 = Èrshíbā Sù (or) Xiù

Skt. = Nakṣatra (or) Aṣṭā-viṃśati nakṣatrāṇi

CELESTIAL DEITIES, HEAVENLY STARS

An astrological grouping from ancient India that refers to 27 or 28 points that the moon passes through in its monthly/annual phases and the associated star constellations found in the cosmic background. Each of these points (constellations) is associated with a deity, although the point-deity association varies among nations and sects. A similar grouping of 28 was developed independently in China. The Chinese merged their system with that from India following the introduction of Buddhism to China around the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. Unlike India, the grouping in China was always 28. It is the Chinese system that was imported by the Japanese. Says Derek Walters (2009): “The inclusion of the 28 moon lodges allowed great precision in regulating the calendar. Virtually all early civilizations worldwide were aware of the occasional need to add an intercalary month to make the seasons align with each particular year. But the Chinese lunar calendar, based on the 28 lunar mansions, was more precise than those of other nations -- it allowed the Chinese to determine in advance and greater precision when a 13th month was needed.” <end quote>

The 28 Moon Lodges or 28 Lunar Mansions (as they are often called in English) are divided into four clusters, with each cluster made up of seven constellations. The four clusters represent the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, west). Each cluster is associated with one of China’s Four Celestial Emblems Guarding the Four Cardinal Directions (black turtle, red bird, blue dragon, white tiger), a Buddhist guardian deity (the Four Heavenly Kings Guarding the Four Compass Directions), a season, a color, and numerous other attributes. These associations and attributes are presented below. In Japan, the 28 deities of the 28 moon lodges are often represented in the Big Dipper Mandala (Hokuto Mandara 北斗曼荼羅) and Star Mandala (Hoshi Mandara 星曼荼羅) of Japan’s esoteric sects. The great complexity of Asian astronomy and Buddhist cosmology gets even more complicated, for there is no single standard for classifying and deifying the celestial bodies. This report presents a brief history of the 28 constellations in China and its later usage in Japanese star worship. This is followed by a lengthy review of the most common groupings of the 4 X 7 = 28 matrix in Japan. This report concludes with a guide to the deification of other important stars and planets, including the Seven Big Dipper Stars, the Nine Luminaries, and the Pole Star (aka Myōken Bosatsu). All together, some 60 deities and over 100 images are presented.

|

Chinese Luopan 羅盤

Feng Shui compass, modern

|

Japanese Rikujinshikiban 六壬式盤

21st Century, Museum of Kyoto

|

|

The Luopan is a cosmographic magnetic compass that allows Feng Shui practitioners to regulate the calendar, identify good/bad influences, and determine precise directions.

|

The shikiban 式盤 is a circular cosmographic divination board used with divination methods called rikujin shikisen, and when invoking the "36 animals" (sanjūrokkin 三十六禽) who have jurisdiction over the hours of the day.

|

|

ROLE OF THE 28 ROLE OF THE 28

IN ANCIENT CHINA

The complete assembly of the 28 occurred sometime in China’s late Zhou or early Han period (sometime between the third-to-first century BCE). Says Derek Walters, an expert in Chinese astrology and Feng Shui 風水 (geomancy): “Each Lunar Mansion belongs to one of the four great seasonal quarters of the sky -- the Dragon, Bird, Tiger and Tortoise -- each being divided, wildly unequally, into seven sections. The seven constellations of the Dragon are visible during Spring nights; those of the Bird in Summer, the Tiger's in Autumn, and the mansions of the Tortoise in Wintertime. Thus, we read in the Zhouyi 周易 Hexagram 1 Qian 乾 that in Winter the Dragon is hidden in the Deep; in Spring it appears on the horizon, in Summer it flies through the sky, and in Autumn, as it begins to set below the horizon, it loses its head.” <source Derek Walters, The Role of the Twenty-eight Xiù [宿] in Feng Shui, 2009> He continues: “ By the time of the early Han (206 BCE - 9 CE), the 28 lunar mansions were inscribed round the outer edge of the Shi 式, the Luopan’s 羅盤 ancestor (see above figures). Very simply, the Shi was a calculating device used in regulating the calendar........it was needed to determine the dates for events of national importance; for fairs, parliaments, and coronations, to gather together dignitaries from far and wide at the right moment, or for buyers and sellers of produce, livestock and manpower to meet when mutually convenient.” <end quote>

|

Scroll, Twelve Zodiac Animals,

by Nagasawa Rosetsu 長沢芦雪

(1754-1799), 18th century.

In private collection of US collector.

Provenance: Erik Thomsen, Europe

|

|

WHAT ABOUT THE MOON’S 12 PHASES & THE ZODIAC? WHAT ABOUT THE MOON’S 12 PHASES & THE ZODIAC?

WHAT ABOUT THE LUNAR CALENDAR? SOLAR CALENDAR?

The Asian zodiac calendar (lunar calendar) is not based specifically on constellations, as is the Western (Greek/Roman) zodiac calendar. Rather, the Asian lunar calendar is based on the twelve yearly phases of the moon, known as the twelve-month lunar year (each month lasting between 28 to 31 days). The Western (Greek/Roman) calendar is based on the annual path of the sun through twelve star constellations, known as the solar year. East Asia’s lunar calendar is also based on 28 Constellations or 28 Moon Lodges (this page), which added greater precision.

Says famed author Isaac Asimov in Words from the Myths (1963) about the Western zodiac: "The heavens contain thousands of stars. These are 'fixed stars' since, unlike the planets, they do not change position with respect to one another. They form patterns that do not change, night after night and year after year. Shepherds and farmers, in prehistoric days, studied these patterns because they served as a calendar. The sun moves against the background of the stars and different stars are visible at night at different times of the year. The easiest way to handle the situation was to divide the stars into convenient groups which are nowadays calld 'constellations' (from Latin words meaning 'with stars'). Then one could say that when one constellation rose in the east at sunset, it was harvest; the rising of another at sunset would indicate planting time and so on. The most important constellations in this connection would be those through which the sun actually passed on its path across the sky. There are twelve of these. The reason for the twelve is that the phases of the moon were also used to keep time. The moon went through its phases twelve times [per year] while the sun traveled through the constellations once. In other words, there are twelve months to the year and the sun spent one month in each of twelve constellations. The natural way of telling one constellation from another is to notice the pattern of stars in each one. It was inevitable that as time went on, people would begin to make complicated pictures out of these patterns. Eight stars arranged in a 'V' might seem to resemble the head of a bull with its horns. Stars arranged in a 'C' might suggest first a bow, and then an archer. As a result, many of the constellations are now pictured as animals or people. In fact the circle of twelve constellations through which the sun passes in its travels contains so many imaginary animals that it is called the 'zodiac' from Greek words meaning 'circle of animals.' The Greeks inherited most of these constellation-pictures from the Babylonians. What they then did was either to change the pictures to fit their own myths, or else invent myths to explain the pictures." <end quote, pp. 44-45>

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

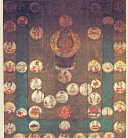

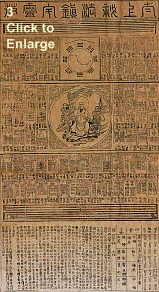

Rectangular Star Mandala

Shingon School

See description below

|

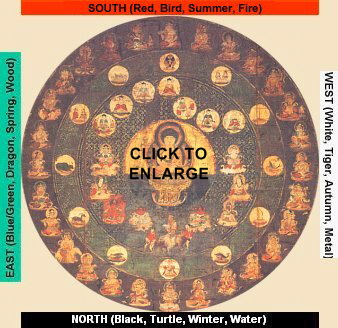

Circular Star Mandala

Tendai, Jimon 寺門 Sect

See description below

|

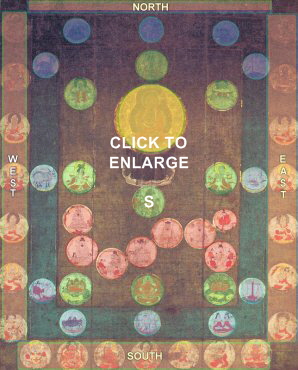

Circular Star Mandala

Tendai, Sanmon 山門 Sect

See description below

|

|

STAR WORSHIP IN JAPAN

THE 28 IN JAPANESE

ART AND RITUAL

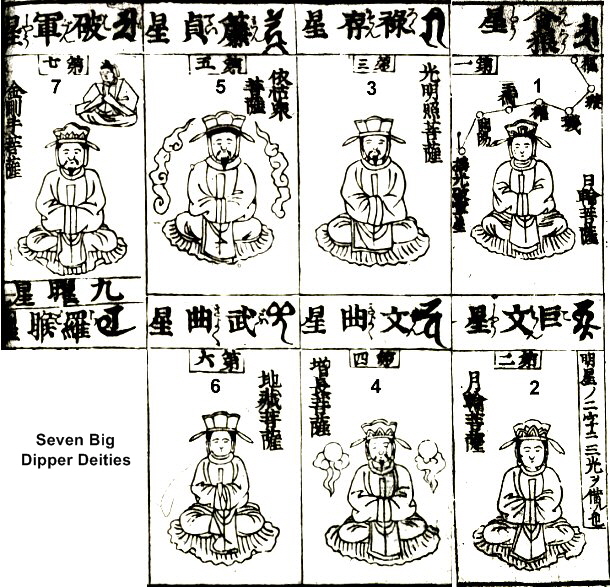

Japan imported China’s Yin-Yang divination and Feng Shui practices in the mid-6th century CE, including astrological lore surrounding star groupings such as the Seven Big Dipper Stars, the Nine Luminaries, the 28 moon lodges, and the 36 animals. The most receptive camps were Japan’s esoteric Shingon and Tendai schools, which took the lead in introducing star worship to Japan. The integration of celestial bodies into Japanese Buddhism peaked during the mid-and-late Heian period, but star faith never developed into a major branch of Japanese esoteric art -- indeed, the number of extant star mandala and star-related masterpieces in Japan is very limited. Star worship is still alive today in Japan <see Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice, 2006>, but it is not a major force in modern religious practice.

One of Japan’s most respected contemporary scholars of star worship is Tsuda Tetsuei 津田徹英. Based on his writings, images of the stars were already created in Japan’s 8th-century Nara period (e.g., Myōken Bosatsu), but at that time there was no standardized iconography for star deities. Artwork from this period was created to follow faithfully the iconography transmitted by Japanese monks who had studied in China. Such art, he says, should be classified as “eclectic esoteric art (zōmitsu 雑密)” in which the deities were worshipped individually with their own invocations (dhāranī 陀羅尼). But later, from the late 9th century to early tenth century, a great number of sutras and esoteric ritual manuals arrived in Japan. This second phase (called Pure Esoteric Art, or Junmitsu 純密) encouraged a “re-examination” of the iconography of the Buddhist deities, and images were thereafter made to match the specifications given in the sutras and ritual texts, and to conform to the structure of the two-world mandala (Womb World & Daimond World). Next, and most importantly for our purposes, comes a third phase. In this third period, starting around the late tenth century CE and extending into the early Muromachi era (13th-14th centuries), comes the emergence of completely new Japanese star deities and their assembly in all-new Japanese star mandala “thanks to the diversification of esoteric schools.” <see Tsuda Tesuei, p. 146, The Images of Stars and Their Significance in Japanese Esoteric Buddhist Art, pages 145-193, in Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice; edited by Lucia Dolce; 2006; special double issue of Culture and Cosmos; ISSN 1368-6534> Essentially, Tsuda Tetsuei believes the structure of Japan’s various star mandala (presented below) has no Chinese precedent. According to him, Japan’s star mandala should be considered as Japanese creations.

|

|

SHINGON RECTANGULAR MANDALA. Star Mandala 星曼荼羅 or Hokuto (Big Dipper) Mandala 北斗曼荼羅. Mid-12th Century, Kumedadera 久米田寺, Osaka. This is the oldest extant star mandala in the rectangular format. Ink, colors, and gold on silk: hanging scroll, 165.1 x 133.2 cm. It was used in Shingon rites to pray for the well-being of the Japanese emperor. COMPOSITION: 28 deities in outer frame, Twelve Zodiac Signs in middle frame, with Nine Luminaries and Seven Stars of Big Dipper in central frame. Largest image near center is Shaka of the Golden Wheel (aka Shaka Kinrin 釈迦金輪, aka Ichijikinrin Butchō 一字金輪仏頂, aka esoteric manifestations of the Historical Buddha).

Photo Source: Enlarged photo from Taosim Art 道教の美術 Exhibition Catalog. 2009. Published by the Osaka Municipal Museum of Art together with the Yomiuri Shimbun, Osaka. Color-coded diagram at left by Schumacher. |

|

|

NORTH (Black, Turtle, Winter, Water)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SOUTH (Red, Red Bird, Summer, Fire)

|

|

|

|

|

|

TENDAI CIRCULAR MANDALA. Hokuto (Big Dipper) Mandala 北斗曼荼羅. Mid-Late 12th Century. Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺, Nara. Kakemono. Color & gold leaf on silk. L = 118.2 cm, W = 83.3 cm. This mandala includes the same components as the prior rectangular Shingon mandala, but the directional axis is reversed. Here the south is at top, with the Seven Stars of the Big Dipper appearing in the upper court and the Nine Luminaries in the lower court. This circular mandala is one of the most famous extant paintings of its type in Japan. Star mandala, either round or rectangular, were used when petitioning for relief from disasters or to pray for longevity. Says the Kyoto National Museum: “These days it is more common to tell fortunes from the twelve signs of the zodiac, but in the old days it was more common to tell fortunes from the seven stars of the Big Dipper. Your fate depended on which of the seven stars was ruling on the month and day you were born. The ruling star on the day the fortune telling is performed was also important. The sun, moon and planets and the twenty-eight signs played secondary roles to the seven stars of the Big Dipper. People prayed to these stars to help prevent disasters and to live longer.” Photo Source: Taosim Art 道教の美術 Exhibition Catalog. 2009.

|

|

|

|

Star worship, astrology, and divination were much in vogue in Japan's Heian era (794 to 1185), especially the late Heian period. This surge in star worship is hard to explain and outside the scope of this article. Indeed, I know little about this surge or why it happened. Below I present what I do know, followed by an annotated visual guide to Japan’s myriad star deities.

- Earliest example of rectangular star mandala was created by Shingon monk Kankū 寛空 (884-972) of the Ninna-ji lineage. The central figure is Sakyamuni of the Golden Wheel (Shaka Kinrin). <source: Tsuda Tetsuei, p. 146, The Images of Stars and Their Significance in Japanese Esoteric Buddhist Art, pages 145-193, in Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice> The most renowned example is preserved at Kumedadera 久米田寺 in Osaka. See photo above.

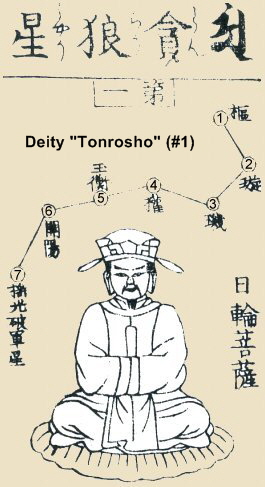

- Circular Sonjō-ō Mandala was created by the Tendai Jimon school. The central figure (representing the Pole Star) is Myōken Bosatsu, but there are many indications that the Pole Star can also be identified with Mercury and with Kannon. Oldest extant example comes from the Besson Zakki 別尊雑記, a Buddhist text compiled by Shingon monk Shinkaku 心覚 (1116-1180) and translated as "Miscellaneous Record of Classified Sacred Images." The mandala’s emergence coincides with the split of the Tendai denomination into two branches -- the Jimon 寺門 and Sanmon 山門. “It may be possible that the Sonjō-ō Mandala was created by Jimon clerics to stand against the ritual of the Sanmon School.” <quote: p. 155, Tsuda Tetsuei>

- Circular star mandala of the Tendai Sanmon branch was created by head abbot Keien 慶円 (949-1019) of the Tendai Sanmon lineage. The central figure is Sakyamuni of the Golden Wheel. <source: p. 156, Tsuda Tetsuei> The most renowned example is preserved at Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺 in Nara. See photo above.

- All three types, says Tsuda, contain star deities and groupings from China, but the structure of these Japanese mandala has no Chinese precedent, and therefore these mandala should be considered as Japanese creations.

- Hokuto Mandala 北斗曼荼羅. Big Dipper Mandala. Used when performing the Hokutohō 北斗法 or "Big Dipper Rite" for averting natural disasters and calamity. This mandara’s most popular appearance in Japan is centered around Shaka Kinrin 釈迦金輪 (Gold Wheel Shaka). Shaka Kinrin is a manifestation of Shaka Buddha (the Historical Buddha), one in which Shaka is holding a golden wheel in his hands, with the latter placed on the lap and the hands forming the Hokkai Jōin Mudra 法界定印 (dharma-realm meditation mudra). In the Hokuto Mandala, Shaka Kinrin is most often shown surrounded by the seven stars of the Big Dipper, by the Nine Luminaries, by the 12 Zodiac Signs, and by the deities of the 28 lunar mansions.

-

|

|

Yakudoshi Chart

(Bad Luck Years)

|

Yakudoshi Talisman

to ward off bad luck

|

|

In Japan today, many temples and shrines have “commercialized” religious cosmology based on Chinese astrological concepts. In Japan the system is called Yakudoshi 厄年, which translates directly as “bad luck years.” It is based on the concept of Chinichi 直日 -- a specific day on which a heavenly body (or bodies) exert an undue influence on earthly affairs. To determine if one's fortune will be good or bad requires a knowledge of the movement of the celestial bodies, including those of the Big Dipper, the Nine Luminaries (five planets, sun, moon, comets, eclipses), the Twelve Signs of the Zodiac, and the Twenty-Eight Moon Lodges (this page). For Japanese men, the most inauspicious ages are 25, 42, and 61. For women, the ages are 19, 33, and 61. This is an oversimplification, mind you. During these unlucky years (and others), people are urged to visit temples and shrines and pay money for rites that will provide divine protection from baleful celestial influences. For reasons unknown to me, the worst years are 42 for men and 33 for women. Many of modern Japan’s temples and shrines aggressively market such beliefs to increase revenues.

- ESOTERIA. Star mandalas from the Kamakura period onward sometimes included images of the Thirty-Six Animals (J = Sanjūrokkin 三十六禽) <see Hillary Pederson, p. 107> By the Edo period, the 36 were combined with guardian warriors and presented pictorially as animal-deity pairs. See, for example, the 1783 Butsuzō zui 仏像図彙 (Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images; jump to Slide #53 to start). Other related terms include Sanjūroku Kingyōzō 三十六禽形像 and Chikusan Reiki 畜産暦. The thirty-six animals appear in both Indian and Chinese cosmological systems. In China, the 36 were divided into four clusters, with each cluster made up of nine animals (4 X 9 = 36). The four clusters represent the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, west). The animals are also grouped in triads -- three animals are combined under one of twelve Zodiac signs (3 X 12 = 36). For a 13th-century list of the animals, see Jōbodai shū 成菩提集 (T8: 728). Also see the Nichū Reki 二中暦, a Japanese calendar from the second half of the 14th century. Like the 28 Moon Lodges, the 36 Animals brought greater precision in determining the calendar. In Japanese divination practices, the 36 animals have jurisdiction over the twelve hours of the day <Kokugauin University, Itō Satoshi> The 28 Lunar Mansions are also said to control the demonic kings of diseases. In the Taoist-inspired tantric-Buddhist text Qiyao Xingchen Biexing Fa 七曜星辰別行法 (T. 21.1309), attributed to Yixing (d. 727), these demonic deities are depicted with human bodies but with various abnormalities. See Journal of Daoist Studies 4 (2011), page 38 for details. Also visit SAT and search for 七曜星辰別行法 -- all the illustrations appear in the online SAT version.

28 Moon Lodges by Directional Cluster

|

NORTH

Seven Lunar Mansions of the Tortoise

(Two Common Japanese Groupings for Seven Northern Moon Lodges)

|

|

GENBU 玄武 (Tortoise)

Black, Winter

Water, Cold, Void

|

|

|

GROUPING ONE - CHINA, JAPAN

Northern Moon Lodges

Japanese Reading | Chinese | Sanskrit

Source: Shukuyō-kyō 宿曜経

|

GROUPING TWO - JAPAN

Deities in GENZU MANDALA 現図曼荼羅

Shingon/Tendai Deities (Celestial Females)

Jp. Reading | Chinese | (Sanskrit) | Deity Name

|

|

1

|

Toshuku 斗宿 Uttara-Aṣāḍhā

|

1

|

Kyoshuku 虚宿 (Dhanistha) 愛財天

|

|

2

|

Gyūshuku 牛宿 Abhijit

|

2

|

Kishuku 危宿 (Satabhisaj) 百薬天

|

|

3

|

Joshuku 女宿 Śravaṇā

|

3

|

Shisshuku 室宿 (Purvabhadrapada) 賢鉤天

|

|

4

|

Kyoshuku 盧宿 Śraviṣṭha (Dhaniṣṭhā)

|

4

|

Hekishuku 壁宿 (Uttara-bhadrapada) 百辞天

|

|

5

|

Kishuku 危宿 Śatabhiṣā

|

5

|

Keishuku 奎宿 (Revati) 多羅天

|

|

6

|

Shisshuku 室宿 Pūrva-Proṣṭhapada

|

6

|

Rōshuku 婁宿 (Asvini) 阿湿毘「イ+爾」天

|

|

7

|

Hekishuku 壁宿 Uttara-Proṣṭhapada

|

7

|

Ishuku 胃宿 (Bharani) 満者天

|

|

TURTLE’S BUDDHIST COUNTERPART = BISHAMONTEN 毘沙門天

Star Chart by Steve Renshaw & Saori Ihara

KEY TO BELOW LIST (corresponds to left column above)

Chinese | Meaning | Jp. Star Reading | Sanskrit Spelling | (Western Constellation)

1. 斗, Dipper / Measure, Hikitsu Boshi, Uttara-Aṣāḍhā (Phi Sgr, Sagittrius)

2. 牛, Cow / Ox, Inami Boshi, Abhijit (Beta Cap, Capricorn)

3. 女, Female, Uruki Boshi, Śravaṇā (Epsilon Aqr, Aquarius)

4. 虚, Emptiness, Tomite Boshi, Śraviṣṭhā / Dhaniṣṭhā (Beta Aqr, Aquarius)

5. 危, Roof Top, Umiyame Boshi, Śatabhiṣā (Alpha Aqr, Aquarius/Pegasus)

6. 室, Room / Encampment, Hatsui Boshi, Pūrva-Proṣṭhapada (Alpha Peg, Pegasus)

7. 壁, Wall, Namame Boshi, Uttara-Proṣṭhapada (Gamma Peg, Pegasus)

|

|

|

SOUTH

Seven Lunar Mansions of the Red Bird

(Two Common Japanese Groupings for Seven Southern Moon Lodges)

|

|

SUZAKU 朱雀 (Red Bird)

South, Red

Summer, Fire

|

|

|

GROUPING ONE - CHINA, JAPAN

Southern Moon Lodges

Japanese Reading | Chinese | Sanskrit

Source: Shukuyō-kyō 宿曜経

|

GROUPING TWO - JAPAN

Deities in GENZU MANDALA 現図曼荼羅

Shingon/Tendai Deities (Celestial Females)

Jp. Reading | Chinese | (Sanskrit) | Deity Name

|

|

1

|

Seishuku 井宿 Punarvasu

|

1

|

Seishuku 星宿 (Magha) 摩伽天

|

|

2

|

Kishuku 鬼宿 Tiṣya (or Puṣya)

|

2

|

Chōshuku 張宿 (Purva-phalguni) 間錯天

|

|

3

|

Ryūshuku 柳宿 Aśleṣā

|

3

|

Yokushuku 翼宿 (Uttara-phalguni) 果徳天

|

|

4

|

Seishuku 星宿 Maghā

|

4

|

Shinshuku 軫宿 (Hasta) 阿悉多天

|

|

5

|

Chōshuku 張宿 Pūrva-Phalgunī

|

5

|

Kakushuku 角宿 (Citra) 質多羅天

|

|

6

|

Yokushuku 翼宿 Uttara-Phalgunī

|

6

|

Kōhuku 亢宿 (Svati) 自記天

|

|

7

|

Shinshuku 軫宿 Hastā

|

7

|

Teishuku てい宿 (Visakha) 尾捨「イ+去」天

|

|

RED BIRD’S BUDDHIST COUNTERPARTS = PHOENIX 鳳凰 & ZŌCHŌTEN 増長天

Star Chart by Steve Renshaw & Saori Ihara

KEY TO BELOW LIST (corresponds to left column above)

Chinese | Meaning | Jp. Star Reading | Sanskrit Spelling | (Western Constellation)

1. 井, Well, Chichiri Boshi, Punarvasu (Mu Gem, Gemini)

2. 鬼, Ogre/Demon, Tamahome Boshi, Tiṣya/Puṣya (Delta Cnc, Theta Cnc, Cancer)

3. 柳, Willow, Nuriko Boshi, Aśleṣā (Delta Hya, Hydra)

4. 星, Star, Hotohori Boshi, Maghā (Alpha Hya, Alphard)

5. 張, Stretched Net, Chiriko Boshi, Pūrva-Phalgunī (Nu Hya, Crater)

6. 翼, Wings, Tasuki Boshi, Uttara-Phalgunī (Alpha Crt, Corvus)

7. 軫, Chariot Cross-Board, Mitsukake Boshi, Hastā (Gamma Crv, Corvus)

|

|

|

EAST

Seven Lunar Mansions of the Blue-Green Dragon

(Two Common Japanese Groupings for Seven Eastern Moon Lodges)

|

|

SEIRYUU 青龍 (Dragon)

East, Blue-Green

Spring, Wood

|

|

|

GROUPING ONE - CHINA, JAPAN

Chinese | Sanskrit Names

Eastern Moon Lodges

Source: Shukuyō-kyō 宿曜経

|

GROUPING TWO - JAPAN

Deities in GENZU MANDALA 現図曼荼羅

Shingon/Tendai Deities (Celestial Females)

Jp. Reading | Chinese | (Sanskrit) | Deity Name

|

|

1

|

Kakushuku 角宿 Citrā

|

1

|

Bōshuku 昴宿 (Krttika) 作者天

|

|

2

|

Kōshuku 亢宿 Niṣṭyā (or Svāti)

|

2

|

Hisshuku 畢宿 (Rohini) 木者天

|

|

3

|

Teishuku 氐宿 Viśākhā

|

3

|

Shishuku 觜宿 (Mrgasiras) 烏頭天

|

|

4

|

Bōshuku 房宿 Anurādhā

|

4

|

Sanshuku 参宿 (Ardra) 米湿天

|

|

5

|

Shinshuku 心宿 Rohiṇī, Jyeṣṭhaghnī

|

5

|

Seishuku 井宿 (Punarvasu) 服財天

|

|

6

|

Bishuku 尾宿 Mūlabarhaṇī (or Mūla)

|

6

|

Kishuku 鬼宿 (Pusya) 増益天

|

|

7

|

Kishuku 箕宿 Pūrva-Aṣādha

|

7

|

Ryūshuku 柳宿 (Aslesa) 不染天

|

|

DRAGON’S BUDDHIST COUNTERPART = JIKOKUTEN 持国天

Star Chart by Steve Renshaw & Saori Ihara

KEY TO BELOW LIST (corresponds to left column above)

Chinese | Meaning | Jp. Star Reading | Sanskrit Spelling | (Western Constellation

1. 角, Horns (perhaps Angle, Corner), Su Boshi, Citrā (Alpha Vir, Spica)

2. 亢, Neck, Throat, Ami Boshi, Niṣṭyā or Svāti (Kappa Vir, Virgo)

3. 氐, Root or Shoulder, Tomo Boshi, Viśākhā) (Iota Lib, Alpha Lib, Libra)

4. 房, Chamber or Breasts, Soi Boshi, Anurādhā (Delto Sco, Pi Scho, Libra)

5. 心, Heart, Nakago Boshi, Rohiṇī or Jyeṣṭhaghnī or Jyeṣṭhā (Sigma Sco, Antares)

6. 尾, Tail, Ashitare Boshi, Mūlabarhaṇī or Mūla (Mu Sco, Scorpius)

7. 箕, Basket, Mi Boshi, Pūrva-Aṣādhā (Gamma Sgr, Eta Sgr, Sagittrius)

|

|

|

WEST

Seven Lunar Mansions of the White Tiger

(Two Common Japanese Groupings for Seven Western Moon Lodges)

|

|

BYAKKO 百虎 (White Tiger)

White, Autumn, Metal

|

|

|

GROUPING ONE - CHINA, JAPAN

Chinese | Sanskrit Names

Western Moon Lodges

Source: Shukuyō-kyō 宿曜経

|

GROUPING TWO - JAPAN

Deities in GENZU MANDALA 現図曼荼羅

Shingon/Tendai Deities (Celestial Females)

Jp. Reading | Chinese | (Sanskrit) | Deity Name

|

|

1

|

Keishuku 奎宿 Revatī

|

1

|

Bōshuku 房宿 (Anuradha) 随事天

|

|

2

|

Rōshuku 婁宿 Aśvayuj (or Aśvinī)

|

2

|

Shinshuku 心宿 (Jyesth) 尊天

|

|

3

|

Ishuku 胃宿 Apabharaṇī (or Bharaṇī)

|

3

|

Bishuku 尾宿 (Mula) 辰天

|

|

4

|

Bōshuku 昴宿 Kṛttikā

|

4

|

Kishuku 箕宿 (Purvasadha) 杏天

|

|

5

|

Hisshuku 畢宿 Rohiṇī

|

5

|

Toshuku 斗宿 (Uttarasadha) 大光天

|

|

6

|

Shishuku 觜宿 Invakā (or Mṛgaśiras)

|

6

|

Gyūshuku 牛宿 (Abhijit) 対主天

|

|

7

|

Shinshuku 參宿 Bāhu (or Ārdrā)

|

7

|

Joshuku 女宿 (Sravana) 寂天

|

|

WHITE TIGER’S BUDDHIST COUNTERPART = KŌMOKUTEN 広目天

Star Chart by Steve Renshaw & Saori Ihara

KEY TO BELOW LIST (corresponds to left column above)

Chinese | Meaning | Jp. Star Reading | Sanskrit Spelling | (Western Constellation)

1. 奎, Stride / Foot, Tokaki Boshi, Revatī (Delta And, Andromeda)

2. 婁, Hill / Lasso / Bellows, Tatara Boshi, Aśvayuj or Aśvinī (Beta Ari, Aries)

3. 胃, Stomach, Ekie Boshi, Apabharaṇī or Bharaṇī (35 Ari, Aries)

4. 昴, Stopping Place / United, Subaru Boshi, Kṛttikā (17 Tau, 16 Tau, Pleiades)

5. 畢, Net (related to Rain?), Amefuri Boshi, Rohiṇī (Epsilon Tau, Taurus)

6. 觜, Turtle Snout, Toroki Boshi, Invakā or Mṛgaśiras (Lamda Ori, Phi Ori, Orion)

7. 參, Investigate / Three, Kagasuki Boshi, Bāhu / Ārdrā (Delta or Beta Ori, Orion)

|

|

|

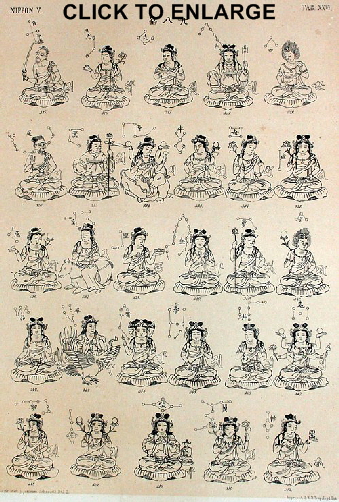

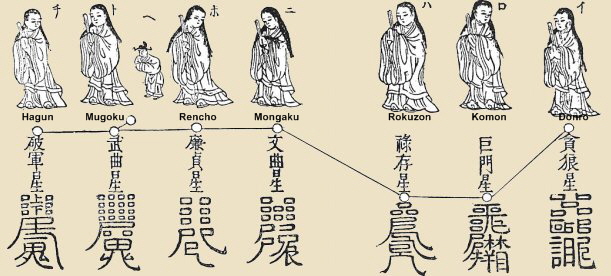

Source of Below Diagram of 28 Celestial Maidens:

Philipp Franz von Siebold. 1832-54 Nippon. Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan.

Nippon Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan, Leiden (1831 CE)

|

|

Image from Nippon Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan, Leiden (1831 CE)

|

|

|

|

Learn about this

monumental

pre-Meiji publication

at this outside site.

|

|

JAPANESE MANTRAS FOR 28 CELESTIAL DEITIES. Courtesy this J-Site

EAST: 東方七宿

1. 昴宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん きりちきゃ のうきしゃたら そわか

2. 畢宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん ろきに のうきしゃたら そわか

3. 觜宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん ひりぎゃしら のうきしゃたら そわか

4. 参宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん あんだら のうきしゃたら そわか

5. 井宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん ぶのうばそ のうきしゃたら そわか

6. 鬼宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん びじゃや のうきしゃたら そわか

7. 柳宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん あしゃれいしゃ のうきしゃたら そわか

SOUTH: 南方七宿

1. 星宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん まぎゃ のうきしゃたら そわか

2. 張宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん ほらは はらぐ のうきしゃたら そわか

3. 翼宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん うったら はらろぐ のうきしゃたら そわか

4. 軫宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん かしゅた のうきしゃたら そわか

5. 角宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん しったら のうきしゃたら そわか

6. 亢宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん そばてい のうきしゃたら そわか

7. 氐宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん そしゃきゃ のうきしゃたら そわか

WEST: 西方七宿

1. 房宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん あどらだ のうきしゃたら そわか

2. 心宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん せいしゅった のうきしゃたら そわか

3. 尾宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん ぼうら のうきしゃたら そわか

4. 箕宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん ふるばあしゃだ のうきしゃたら そわか

5. 斗宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん うったらあしゃだ のうきしゃたら そわか

6. 牛宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん あびしゃ のうきしゃたら そわか

7. 女宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん しらまな のうきしゃたら そわか

NORTH: 北方七宿

1. 虚宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん だにしゅた のうきしゃたら そわか

2. 危宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん しゃたびしゃ のうきしゃたら そわか

3. 室宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん ほらば ばつだらやち のうきしゃたら そわか

4. 壁宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん うたのう ばっだらば のうきしゃたら そわか

5. 奎宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん りはち のうきしゃたら そわか

6. 婁宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん あしんび のうきしゃたら そわか

7. 胃宿 のうまく さんまんだ ぼだなん ばらに のうきしゃたら そわか

|

|

Genzu Mandala (Mandara) 現図曼荼羅

Literally the “current depiction” of the Taizōkai Mandala 胎蔵界曼荼羅 in Japan, commonly known in English as the Womb World Mandala. Says JAANUS: “A version of the Taizōkai Mandala that is widely used today in Japan. The original version, brought to Japan from China by Kūkai 空海 (774-835), was kept at Tōji Temple 東寺 (Kyoto), but because it began to show signs of wear in Kūkai's later years, a copy was made in 821, year of the reign of Emperor Kōnin 弘仁, so this first copy is known as the Kōnin Version. The version presently used at Tōji is the fourth copy, made in the Genroku 元禄 era (late 17c), and is known as the Genroku Version. In addition, three mandala 曼荼羅 fragments were discovered in 1954 in the attic of the treasure house (hōzō 宝蔵) at Tōji Temple, and of these the so-called Kōhon 甲本 (Version A) is thought to be a fragment of the second copy of the Genzu Mandala, made in 1191, while the so-called Einin 永仁 Version is thought to be a fragment of the third copy, made in 1296 (Einin 4). The Genzu Mandala is considered to have been brought to completion by Kūkai's teacher, Huiguo 恵果 (Jp. = Keika, 746-805), and it represents the final form of the Taizōkai Mandala, which evolved from the mandala of the Dainichi-kyō 大日経 (Skt. = Vairocanabhisambodhi Sutra) via the Taizō Zuzō 胎蔵図像 and Taizō Kyūzuyō 胎蔵旧図様. Its composition varies somewhat, but it consists of approximately 400 deities systematically arranged in 12 sections called:

- Chūdai-hachiyō-in 中台八葉院

- Henchi-in 遍知院

- Jimyō-in 持明院

- Rengebu-in 蓮華部院

- Kongōshu-in 金剛手院

- Shaka-in 釈迦院

- Kokūzō-in 虚空蔵院

- Monju-in 文殊院

- Soshitsuji-in or Soshitchi-in 蘇悉地院

- Jizō-in 地蔵院

- Jogaishō-in 除蓋障院

- Gekongōbu-in 外金剛部院 (the 28 deities typically appear in this section)

Compared with the approximately 120 deities mentioned in the Dainichi-kyō this represents a more than threefold increase in the number of deities. The term "Genzu 現図 (current depiction) was first used by Godai-in Annen 五大院安然 (841-889/898?) of the Tendai 天台 sect. Later, in his Shosetsu Fudōki 諸説不同記 a detailed comparison of the iconography of the deities depicted in the Taizōkai Mandala, the imperial prince and Buddhist priest Shinjaku 真寂 (886-927) used the term to designate the orthodox Taizōkai Mandala as transmitted by Kūkai in contradistinction to that brought to Japan by Shūei 宗叡 (809-884) and preserved in the Tendai sect, and it subsequently passed into general usage. The term "Genzu" should therefore be used to refer to the current depiction of the Taizōkai Mandala.” <end JAANUS quote>

|

|

Myōken Spellings / Readings

Jp. = Sonshō-ō 尊星王

Jp. = Sonjō-ō 尊星王

Jp. = Myōken Son 妙見尊

Jp. = Myōken Bosatsu 妙見菩薩

Jp. = Myōken Daibosatsu 妙見大菩薩

Jp. = Chintaku Reifujin 鎮宅霊符神

Jp. = Hokushin Bosatsu 北辰菩薩

Jp. = Hokuto Myōken 北斗妙見菩薩

Jp. = Hokuto-ten 北斗天

Jp. = Taiisu Hokushin Sonjō 太一北辰尊星

Jp. = Taiitsu Jōtei 太一上帝 (Confucianism)

Jp. = Taikyoku Genshi 太極元神 (Diviners)

Jp. = Ame no Minakanushi 天御中主尊

Jp. = Kunitokotachi no Mikoto 国常立尊

Jp. = Myōken-shin or Myōken-jin 妙見神

Jp. = Shinmu Taiitsu Jōtei Reiō Tenson

真武太一霊応天尊

Sanskrit = Sudarśana, Sudrsti

Chn. = Miàojiàn Púsà (Miao Chien)

Krn. = Myogyeon Bosal, 묘견보살

Myōken Mantra

おん そぢりしゅた そわか。

おん まかしりえい しべい そわか

On Sochirishuta Sowaka

On Makashiri-ei Shibei Sowaka

Myōken Sanskrit Seed

Pronounced SO in Japanese

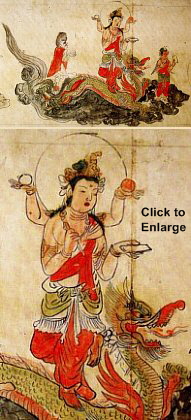

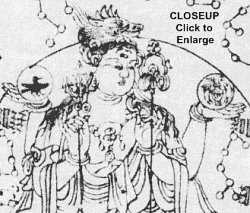

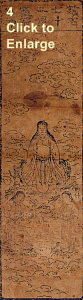

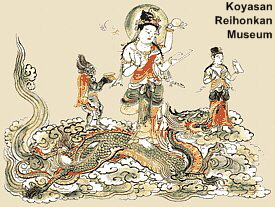

4-armed Myōken atop dragon, holding sun & moon discs, and brush & tablet (on which s/he records our good/bad deeds). Handscroll, color on paper. Kamakura Era (13th-14th century). Important Cultural Property ICP. Treasure of Shōmyō-ji Temple 称名寺, Kanagawa, but now housed by the Kanagawa Prefectural Kanazawa Bunko Museum 神奈川県立金沢文庫保管. Image based on drawing in the Zuzōshō (Zuzosho) 図像抄, or the Encyclopedia of Buddhist Icons, a text edited by Ejū 恵什 (1060-1145 AD). Photo courtesy Taoism Art Catalog.

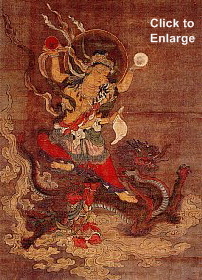

Hokushin 北辰 (Polar Star Deity), aka Myōken Bosatsu 妙見菩薩, dressed as warrior, holding sword. L = 113.8 cm, W = 40.4 cm, Color on Silk, 14th Century, Tōji Temple 東寺, Kyoto. A similar portrayal of Myōken appears in scroll 29 of the Rōya Daisuihen 琅邪代酔篇, compiled by Chō Teishi 張鼎思 (1543-1603). <Photo: Treasures of Tōji Temple.

1995 Exhibit Catalog. Asahi Shimbun.>

Standing image of Myōken Bosatsu.

By Immyō 院命. Wood. H = 155.1 cm.

Kamakura Era (dated 1301). ICP.

Photo courtesy Taoism Art Catalog.

Sonshō-ō 尊星王 (aka Myōken). Skt. = Sudrsti. Monarch of the Venerable Star. Holds sun & moon disks, stands atop

dragon. Hanging Scroll, Color on Silk.

H = 99.8 cm, W = 57.9 cm.

Muromachi Era, 15th Century.

Mimuroto-ji Temple 三室戸寺, Kyoto

Photo courtesy Taoism Art Catalog.

Worshipped to avoid calamities of

fire and to heal eye diseases.

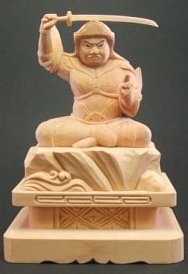

Modern Myōken Statue. Holding

sword over head, which is a common

portrayal of the deity among samurai.

Photo: This J-store.

Hokuto-ten 北斗天 (Big Dipper Myōken)

in the guise of a Bodhisattva. Drawing from the 17th-century Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙

|

|

|

|

|

Myōken 妙見 (Skt. = Sudrsti, Sudarśana) Myōken 妙見 (Skt. = Sudrsti, Sudarśana)

Deification of North Pole Star,

the Little Dipper and the Big Dipper

Origin = Chinese folk worship of the North Pole Star.

Myōken is the deification of the North Pole Star (Hokushin 北辰) of the Little Bear constellation (Ursa Minor), as well as the deification of the Big Dipper (Ursa Major). The term Myōken 妙見 literally means heavenly eyes, heavenly sight, penetrating sight, one who sees all, or simply “good eyesight.” In Japan, worship of the northern Pole Star along with the seven stars of the Big Dipper (Hokuto Shichisei 北斗七星) is a syncretic blend of Buddhism, Taoism, Onmyōdō 陰陽道 (Yin-Yang Divination), and local kami cults, but it is especially important within Esoteric Buddhism, and from the Heian period (794-1180) onward, Myōken was venerated under various guises as the central star controlling all other celestial bodies, one believed to control the life and fortunes of the people, one who protected not only the emperor and country, but also warded off diseases, prevented calamities of fire and other disasters, increased life spans, and healed eye diseases. As a deification of the Pole Star, Myōken was also worshipped as the deity of safe voyages and navigators. In Japan, even today, s/he is venerated at both Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines. However, since the forced separation of Buddhism and Shintōism in the Meiji Period (1868-1912), shrines commonly replaced Myōken with a Shintō kami counterpart known as Ame no Minakanushi no Mikoto 天御中主尊 (Lord of the Center of the Sky). Details below.

Myōken goes by many different names in Japan. The Japanese court regarded the Pole Star as an imperial symbol and worshipped its deification as Sonshō-ō 尊星王 (Sonjō-ō, Sonsho-o, Sonsei-ō; the “Monarch of the Venerable Star”), but in the eastern provinces and among samurai warriors, the deity was venerated as Myōken 妙見, Myōken Son 妙見尊, or Myōken Daibosatsu 妙見大菩薩. In Yin-Yang circles (Onmyōdō 陰陽道), the deity was prayed to as Chintaku Reifujin 鎮宅霊符神, who in turn was sometimes known as the Taoist deity Taizan Fukun 泰山府君 or Taiichi 太一, the Great One. <Source: Lucia Dolce, pp. 16-17, The Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice> As a deification of the North Pole Star, Myōken is closely associated with the Little Dipper (where the north star is located). But because of confusion between the Little Dipper and Big Dipper, she is also known as Hokushin Bosatsu 北辰菩薩 (Pole Star Myōken), Hokuto Myōken Bosatsu 北斗妙見菩薩 (Big Dipper Myōken), or Hokuto-ten 北斗天 (Deva of the Big Dipper).

Myōken is also held in high esteem, even today, by Japan’s Nichiren sect, for the deity reportedly assisted sect founder and radical reformer Nichiren Shōnin 日連上人 (1222-82). Among samurai and peasants, Myōken is considered the guardian of warriors, horses, and farmers, and is worshipped in this role especially at sacred Mt. Myōken in Nose 能勢妙見山 (near Osaka), a Nichiren stronghold, where Myōken appears as a warrior brandishing a sword over his head (see photo below). Horses were especially important in battle and in harvesting crops, hence the association with warriors and farmers. In the Jimon 寺門 branch of the Tendai 天台 sect, Myōken images resemble or are equated with Kichijōten 吉祥天 (the Goddess of Beauty, Fertility, Prosperity, and Merit).

The first evidence of the Myōken cult at the Japanese court is recorded in 785 AD <source: Nakamura p. 85>. By the early 9th century, stories of Myōken’s miraculous powers appeared in the Nihon Ryōiki 日本霊異記 (aka Nihon Rei-iki or Nippon Reiiki). The full title of this text is Nihonkoku Genpō Zen'aku Ryōiki 日本国現報善悪霊異記, commonly translated as "Miraculous Stories of Karmic Retribution of Good and Evil in Japan.” In this book of Buddhist legends, Myōken appears in the form of a deer to help (1) devotees recover stolen silk robes and (2) to help worshippers discover a thief (a temple acolyte who steals money from the donations of Myōken devotees). In another story from the same text, a fisherman whose boat is destroyed in a storm is rescued from certain drowning because of his faith in Myōken. <Source: The Nihon Ryōiki of the Monk Kyōkai, translated and edited by Kyoko Motomochi Nakamura, published 1973; see pages 85, 149, 229, and 266-267>

Myōken Iconography & Rituals

Although considered a Bosatsu (Skt. = Bodhisattva), Myōken is more properly classified as a Deva (Jp. = TEN). Myōken’s attributes are not firmly set, and thus s/he comes in various manifestations in Japan. For instance, the deity generally appears with two or four arms, and is shown seated on a cloud or standing atop a dragon, or a turtle, or a composite beast known as the Kida 亀蛇 (half turtle, half dragon-snake). One of the most popular modern forms of Myōken shows the deity standing atop a turtle (the ancient Chinese guardian of the north). Another popular modern depiction shows the deity as a warrior, holding a sword above his head and wearing helmet and armor. In statuary and mandala artwork, Myōken imagery is commonly combined with representations of the Seven Stars of the Big Dipper. Myōken’s female form, in some locations, is considered a manifestation of Kannon Bosatsu and is venerated as the goddess of the home and prayed to for domestic harmony, as at Kōdō Temple 革堂 (the 19th temple along the 33-Site Saigoku Kannon Pilgrimage). Other heterodox views identify Myōken with Shaka Nyorai (the Historical Buddha) or with Yakushi Nyorai (the Medicine Buddha). The oldest extant representations of Myōken (see photos below) depict the deity with right foot raised and resting behind the opposite knee, while the hands hold the sun and moon discs (befitting icons symbolizing Myōken’s role as the supreme celestial deity, one “lighting” the way along the path of enlightenment). Such iconography is considered unique to Japan, for no trace of it can be found on the Asian continent. The sun disc sometimes contains a three-legged black crow, while the moon disc sometimes contains a hare and/or toad. Myōken also commonly carries a brush and tablet (on which s/he records our good/bad deeds). S/he is sometimes surrounded by a male Yasha-like creature holding an inkstone and/or a female attendant holding a tablet and brush, or depicted as a royal dressed in courtly gowns. Some of the most important rituals devoted to Myōken, the Pole Star, and the Big Dipper include:

- Myōken-hō 妙見法, the Rite to Myōken. Held in modern times during adverse weather or when natural disasters threaten society.

- Hokuto-hō 北斗法, the Rite of the Big Dipper. Came to prominence during the Insei period 1086-1192. Held in modern times during adverse weather or when natural disasters threaten society.

- Sonjō-ō-hō 尊星王法, the Rite of Sonjō-ō (aka Myōken). Sonjō-ō can be translated as “Monarch of the Venerable Star.” Performed to prevent calamities; one of four imperial rites traditionally performed at Miidera Temple 三井寺 (aka Onjōji Temple 園城寺) in Shiga Prefecture. Came to prominence during the Insei period 1086-1192 AD. In this rite, Sonjō-ō is considered to represent the entire cosmos (not just the Pole Star); the rite, accordingly, combines a multitude of celestial deities into a single visualization of Sonjō-ō. <Source: Gaynor Sekimori, pp. 234-236, The Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice.>

- Yamamiya-sai 山宮祭, or Mountain Shrine festival/rite, held from the late 9th century until the late Edo period by members of the Watarai clan of Ise priests at Okazaki Shrine 岡崎 (located on the grounds of the Jōmyōji Temple 常明寺, a Watarai clan temple midway between the Inner and Outer Shrines at Ise). Devoted to the worship of the Pole Star, the sun and the moon, and eventually to the protective deities of the 12 months of the year and the 28 Lunar Mansions. <Source: Mark Teeuwen, p. 91-92, The Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice.>

- Myōken’s Ennichi (Holy Day). The 15th day of each month is considered Myōken’s Ennichi 縁日, literally "related day" or “day of connection.” This is translated as holy day, one with special significance to a particular Buddha or Bodhisattva. Saying prayers to the deity on this day is believed to bring greater merits and results than on regular days. Since the full moon appears on the 15th each month in the old lunar calendar, it is an appropriate ENNICHI for Myōken. Says the Digitial Dictionary of Buddhism (login = guest): “The deity is understood to be in special charge of mundane affairs on that day, e.g. the 5th is Miroku, 15th Amida, 25th Monju, 30th Shaka. According to popular belief, religious services held on such a day will have particular merit.” <end quote> See Ennichi list for 30 Deities (Sanjūn Nichi Hibutsu 三十日秘仏; J-only).

Myōken and Ame no Minakanushi

Myōken worship suffered when the Meiji government forcibly separated Shintō and Buddhism (Shinbutsu Bunri 神仏分離) in the late 19th century. Between 1868-1875, when the government actively outlawed all fusion of the Kami-Buddha, the Buddhist deity Myōken was commonly replaced with the Shintō kami Ame no Minakanushi no Mikoto 天御中主尊 (a primordial ancestral kami), who then served as the chief kami of the seven major stars of the constellation of the Big Dipper (Ursa Major). Ame no Minakanushi is generally translated as "Lord of the Center of the Sky." This kami appears in the Kojiki 古事記 (Record of Ancient Matters, 712 AD, Japan's oldest record of its creation myths), and from 12th-century texts onward, the deity is generally interpreted as equivalent to the Pole Star. (Also spelled: 天之御中主神, Amenominakanushi, Amanominakanushi, Amaterasu). Sources: Kokugakuin University; and Mark Teeuwen, p. 92>

Says the Encyclopedia of Shinto: “Japanese scholar Hirata Atsutane, in particular, propounded a theology wherein Ame no Minakanushi no Mikoto 天御中主尊 was chief kami of the seven major stars of the constellation Ursa Major. As a result of this influence, Ame no Minakanushi was made a central deity at the Daikyōin Temple in the early Meiji period, and he was worshiped within sectarian Shintō (Kyōha Shintō) as well. During the process of separation of Shintō and Buddhist objects of worship, the deity Myōken (the north star) was changed to Ame no Minakanushi at many shrines. <end quote> Many Suitengu Shrines throughout modern Japan still revere Amenominakanushi -- which can be roughly translated as “Chief of All Celestial Deities,” thus retaining the nuance of Myōken’s exalted position among all stars. For an excellent review of Myōken in modern times, see story by scholar Gaynor Sekimori entitled "Star Rituals and Nikkō Shugendō," which appeared in The Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice., pages 217-250, edited by Lucia Dolce; a special double issue of Culture and Cosmos, ISSN 1368-6534. Elsewhere, says scholar Mark Teeuwen, p. 92: “At Ise shrines, from the 12th century onwards, Ise priests wrote texts claiming that the deity of the Outer Shrine at Ise was identical to Ame no Minakanushi (the first deity of creation in the Kojiki).” <end quote Teeuwen>

Myōken Lore from Other Sources

Says JAANUS: “Myōken is an amalgamation of the Shintō deity Myōken Shin 妙見神 and the deity of the Northern Polar Star (Little Dipper). Originally a deification of the Polestar (Hokushin 北辰) but later also regarded as a deification of the Big Dipper (Hokuto 北斗) because of confusion between the two. Although popularly regarded as a Bodhisattva 菩薩, and usually referred to as Myōken Bosatsu 妙見菩薩, properly speaking s/he belongs to the category of divinities called TEN 天 (Skt. = Deva), and in the Jimon 寺門 branch of the Tendai 天台 sect she is equated with Kichijōten 吉祥天. She is invoked in particular for apotropaic purposes and also for the healing of eye diseases. In Japan she appears to have been widely revered as early as the Heian period, and in medieval times she came to be worshipped especially among powerful provincial clans as a tutelary deity of the warrior class, evolving into the partially Shintōized deity Myōkenjin 妙見神. At the same time she was also adopted by the Nichiren 日蓮 sect and remains the object of a popular cult today. Artistic representations of Myōken exhibit considerable diversity. There is a set of 26 paintings, all different, at Daigoji Temple 醍醐寺 in Kyoto, but generally speaking she is depicted with either two or four arms and either seated on a cloud or standing on the back of a dragon. Myōkenjin has a halo showing the seven stars of the Big Dipper and holds a sword in one hand. There is also a mandala (mandara) 曼荼羅 devoted to her, the Myōken Mandala 妙見曼荼羅.” <end JAANUS quote>

Says the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism. Sign in with user name = guest. “Myōken Bosatsu. The beautiful sight, i.e. Ursa Major, or the bodhisattva who rules there. He symbolizes the Great Bear, and is venerated in esoteric Buddhism and the Nichiren Sect. This bodhisattva is believed to protect the country, ward off disease and increase one's life-span. In Japan he is popularly believed to cure eye diseases. Also called 妙見大士, though some say Śākyamuni, others Avalokitêśvara, others 藥師 Bhaiṣajya, others the Seven Buddhas. His image is that of a youth in golden armor. Transliterated as 藪達梨舍菟. The Iwanami dictionary has a detailed entry. 〔密成就儀軌 T 1205.21.36b5; sources cmuller, Nakamura, Soothill, JEBD].” <End DDB quote>

Says site contributor Gabi Greve: “Myōken is a purely Japanese Bosatsu, presumably an amalgamation of the Shinto deity Myooken Shin 妙見神 and the deity of the Northern Polar Star (Dipper). He (sometimes seen as a SHE) has been the protector deity of the clan of the CHIBA 千葉 since the Heian period. This clan later became followers of Nichiren, therefore Myooken is often venerated in temples of this sect. Myooken protects from fires, brings luck and prosperity and heals illness of the eyes. In Edo he was very popular, since there were many fires in the city. So festivals of Myooken were visted by many townspeople and always full of merrymaking. He also takes care of the behaviour of human beings and writes your good and bad deeds in his notebook. He is also venerated as a special protector deity of the land and country of Japan. He stands on a tortoise with a thick tail or rides a green dragon. He is accompanied by a vassal who carries pen and paper (remember, he registers all our deeds). His hair is long and hanging down, like the fashions popular in the Heian period. He carries a sword and a wish-fulfilling jewel. Sometimes he is depicted with four arms, two of them carrying the sun and the moon. In Japan, most of his statues are made of stone.” <end Gabi quote>

Myōken Photos with Reference Notes

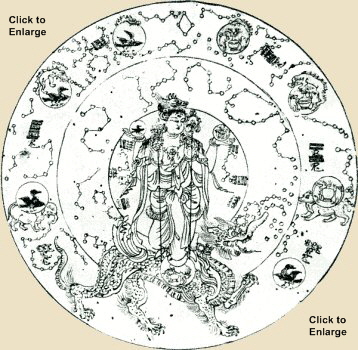

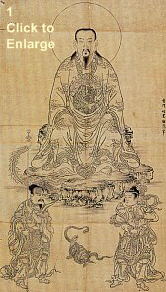

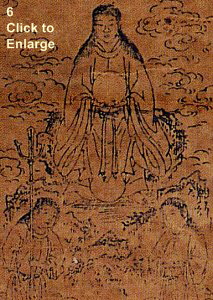

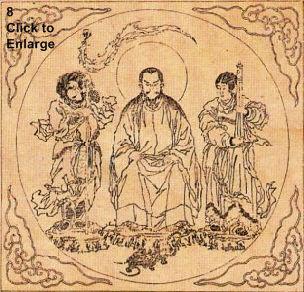

ABOVE TWO DRAWINGS: 12th-century monochrome drawing of the Sonjō-ō (or Sonshō-ō) Mandala 尊星王曼荼羅 from the Besson Zakki 別尊雑記, the oldest extant example of this mandala. The above Sonjō-ō Mandala is attributed to the Jimon 寺門 branch of the Tendai 天台 sect based at Miidera Temple 三井寺 (aka Onjōji Temple 園城寺) in Shiga Prefecture. The Besson Zakki is a Buddhist text compiled by Shingon monk Shinkaku 心覚 (1116-1180) and translated as "Miscellaneous Record of Classified Sacred Images." Also called the Gojukkanshō 五十巻抄. The Sonjō-ō Mandala was used in rituals to secure the health and longevity of the emperor. The above drawing depicts Sonjō-ō (aka Myōken) with four arms, standing atop a dragon. Various stars and constellations appear in three concentric circles around the deity, “which seem to reflect the pattern of the night sky in the northern hemisphere.” <source Tsuda Tetsuei pp. 145-194>. The deity holds the sun disk (with a three-legged black crow inside), moon disk (with a rabbit and frog inside), a trident (Gekihoko 戦鉾), and a staff (Shakujō 錫杖) with metal rings. The deity stands on one leg, with the right foot raised behind the opposite knee, forming the shape of the numeral four -- this pose is said to symbolize the ritual steps (uho 禹歩) used in Onmyōdō 陰陽道 (Yin-Yang practices) or the magical step called the Pace of Yu (henbai uho 反閇禹歩) used in contemporary Shugendō practices to create sacred boundaries. A crocodile-like creature (makatsu 摩竭) appears atop the deity’s head, although in most other portrayals the animal atop Myōken’s head is commonly a deer, said to be Myōken’s messenger or manifestation. Various other creatures appear, including an elephant, a white fox, and numerous three-legged black crows. The crow is associated with the sun and with Amaterasu Ōmikami 天照大神 (Japan’s supreme sun goddess). The hare is associated with the moon, as is the frog because of its bumpy skin. See below for details on this iconography. The vases that appear in the drawing contain the elixir of immortality. <Sources: Tsuda Tetsuei pp. 145-194, and Gaynor Sekimori pp. 217-250 in The Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice.>

Sonjō-ō (or Sonshō-ō) Mandala 尊星王曼荼羅

Four-armed Sonjō-ō (aka Myōken) standing atop a dragon, Kamakura period, 13th century.

Treasure of Miidera 三井寺 (Shiga). H = 68 cm, W = 42 cm. ICP. Color on silk. Horned deer atop head.

Holding sun & moon discs; 3-legged crow 三足の烏 inside sun disc; hare 兎 and frog 蛙 inside moon disc.

The outer rim of eight sun & moon discs depict a deer 鹿, leopard 豹, white fox 白狐, tiger 虎, and elephant 象,

as well as more three-legged crows and hare-frog pairs surrounding a vase containing the elixir of immortality.

LEFT PHOTO: Photo from Miidera Temple’s J-site. RIGHT (REPRODUCTION): Photo from this J-site.

ABOVE TWO PAINTINGS: The 13th-century Sonjō-ō (or Sonshō-ō) Mandala 尊星王曼荼羅 at Miidera Temple 三井寺 (aka Onjōji Temple 園城寺) in Shiga Prefecture is in bad repair, but the origin of its iconography has “exercised scholarly minds for centuries,” according to scholar Gaynor Sekimori in "Star Rituals and Nikkō Shugendō" (pp. 217-250, The Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice). Says Sekimori: “The 12th-century text Kakuzenshō 覚禅鈔 suggests an iconographic relationship with the water star (Mercury) in the mandala devoted to Butsugen 仏眼曼荼羅, and associations have also been made with two other deities of the north, Kichijōten and Bishamonten. The Miidera painting portrays Sonjō-ō as a four-armed Bodhisattva standing on a green dragon with one foot raised behind the opposite knee. It is closely related to one of the three standard Myōken iconographical depictions, but differs in that the second set of hands holds, not pen and paper, but a shakujō (staff) and trident. It has been suggested that the leg position represents the magical step callled the Pace of Yu (henbai uho 反閇禹歩) used in contemporary Shugendō to create sacred boundaries. The dragon represents the Pole Star and the Dipper constellation. The image stands on the moon, associated with night and so the Pole Star. The eight sun and moon discs (probably the eight basic hexagrams representing cosmic balance) contain the three-legged crow and a rabbit and frog respectively. Both are originally Chinese representations associated with the sun and the moon. The vase in the center of the moon represents the container of the medicine of immortality, and the frog is associated with the moon because of its bumpy skin. The provenance of the animals on the outer rim has been described as an 'eternal riddle' but there are indications to suggest their reference. First, a horned deer appears both on the head of Sonjō-ō and above the upper sun and moon. One explanation is that it is there to suggest a connection with Kasuga Shrine; certainly the Fujiwara, whose clan shrine Kasuga was a major patron of Miidera, and the Sonjō-ō rite, was performed to protect Fujiwara empresses in childbirth. Another explanation is that the deer was associated with Chinese immortals. Yet another connection is offered in tales collected in the Nihon Ryōiki (see stories above). The Miidera painting includes a tiger and a panther (or leopard), and shares [with the Besson Zakki image above] an elephant and a white fox. The panther (Kisuihyō), tiger (Bikakō), and fox (Shingekkō) are associated with three constellations that protect the northeast (Kishuku, Bishuku, and Shinshuku), and so may be regarded as guardians of the direction from which the most baleful influences come. [Editor's Note: The northest is known as the 'Demon Gate' in Japan (Kimon 鬼門), a Japanese term stemming from Chinese geomancy (Ch: feng shui 風水). In Chinese thought, the northeast quarter is considered particularly inauspicious. It is the place where "demons gather and enter." This Chinese belief was imported by the Japanese, who believe the fox is particularly adept at protecting the NE direction from evil influences.] The elephant may represent Fugen Bodhisattva, a deity of long life, and indeed the mantra of Enmei Fugen (Long Life Fugen) is recited during the Sonjō-ō ritual. The concentric circles are stylizations of what appears in the Kakuzenshō drawing and in standard star mandala as the Nine Luminaries, the Twelve (12) Celestial Mansions, and the Twenty-Eight (28) Constellations.” <end quote Gaynor Sekimori>

Myōken, Deity of the Pole Star and Little / Big Dipper

ABOVE TWO DRAWINGS: Modern reproductions of the Sonjō-ō Mandala at Miidera Temple.

See prior photo of original. Shows three-legged crow inside sun disk & rabbit-frog inside moon disk.

Horned deer appears on the head of Sonjō-ō and above the upper sun and moon. Photos this J-Site.

|

Rokuji Myō-ō 六字明王

Literally “Six-Syllable Luminescent King.” The below two drawings share certain iconographical similarities with the 12th-century monochrome drawing of Myōken (see prior photos) and the 13th-century painting of Sonjō-ō at Miidera (see prior photos). In all of them, we see the four-armed one-headed central deity holding the sun disk and moon disk, with right foot raised behind the opposite knee. However, in the below drawings, the deity is portrayed atop a lotus, whereas the earlier images show her atop a dragon. The drawings also portray the deity holding different objects. Rokuji Myō-ō appears in the Rokuji Jinjuōkyō 六字神咒王經 sutra, where the deity is described as the central icon (honzon 本尊) in esoteric rituals (known as the Chōbuku Shinpō 調伏信法 or Chōbuku-hō 調伏法) to ward off evil spirits, enemies, and malicious influences.

|

|

|

|

Click to Enlarge

Rokuji Myō-ō 六字明王

Drawing from 12th-century Japanese text

Besson Zakki 別尊雑記, translated as

Miscellaneous Record of Classified Sacred Images

|

Click to Enlarge

Rokuji Myō-ō 六字明王

Literally “Six-Syllable Luminescent King.”

17th-century drawing from

the Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙

|

|

|

|

Notes on the Rokuji Mandala 六字経曼荼羅. Also called the Rokujikyō (Rokujikyo Mandala), literally Six Letter Mandala or Six-Syllable Incantation. Centered on Shaka Nyorai 釈迦 (the Historical Buddha) holding a gold wheel (hōrin 法輪). See Hokuto Mandala (Big Dipper Mandala) for more about this form of Shaka. The central deity is surrounded by Six Kannon (Roku Kannon 六観音), and the group of seven appear within a moon disc. At the top of the mandala are two flying celestials (hiten 飛天); at the bottom are images of Fudō Myō-ō 不動明王 and Daiitoku Myō-ō 大威徳明王, and positioned between them are six figures venerating a smaller moon disc. The deity is also said to be the composite reward body (総合成就身) of the Roku Kannon who protect people in each of the six realms of karmic rebirth. Says JAANUS: “Images of the Six Kannon began to be made as offerings for the welfare of the dead and for personal salvation in the first half of the 10th century. The Six Kannon appear in the most common form of the Rokujikyō Mandala, which from the Heian period was the focus of the Rokujikyōhō 六字経法, a Shingon ritual used particularly for sickness and childbirth. The six forms of Kannon often appear along with their corresponding Sanskrit bonjimon 梵字文. <end JAANUS quote>

|

|

|

|

ABOVE TWO DRAWINGS: Myōken images from pre-Meiji Japan. LEFT: Four-armed Myōken holding brush and tablet (in which s/he records all one’s deeds), a sword, and the wheel of law. Six or seven snakes appear atop head. RIGHT: Holds brush & tablet, sun & moon disks; stands atop dragon & five-colored cloud (Goshiki Un 五色雲), right foot raised & resting behind opposite knee; a semi-divine male Yasha 夜叉 attendant stands atop a black cloud holding an inkstone. Sources: Butsuzō Zukan 仏像図鑑, V. One, pp. 139-140. This iconographical document was compiled by Buddhist monk Gonda Raifu 権田雷斧 (1847-1934); available for online purchase. Also see 大全書、日本仏像 ISBN4-88405-335-4 C0095.

Nose Myōken Daibosatsu 能勢の妙見大菩薩 (dated 1824)

Tanba Risshōzan Myōhōji Temple 丹波, 立正山, 妙法寺, Hyōgo Prefecture

Nose was the name of a feudal lord, and the Nose domain is near Osaka.

Mt. Myōken in Nose 能勢妙見山 (near Osaka) is a famous and sacred site of the Nichiren sect.

Myōken of Nose protects the nation, eradicates evil, vanquishes enemies in the battlefield,

protects horses, and brings happiness and longevity to the people. The temple is

affiliated with the Nichiren Sect. It holds an annual Myōken festival in late July. Photo this J-Site.

|

Chiba Mon

Moon-Star Crest

|

|

Chiba Moon-Star Crest (The Emblem of Myōken)

From History of Reiki, Vol. 2, Miscellaneous Research,

by James Deacon, 2002, Page 10

http://www.scribd.com/doc/133006/Reiki-History-Vol-2

"The moon-star crest (as used by the Chiba) was originally (and still is) the emblem of Myōken Bosatsu. During the Heian period, Myōken was adopted as the tutelary deity of the Chiba clan, and along with the bosatsu, they adopted the 'moon-star' crest as their mon. It seems this adoption was in recognition that Myōken had afforded protection in battle to one of the Chiba-clan ancestors." |

|

Chintaku Reifujin 鎮宅霊符神

Also known as the “Tutelary God of Houses” in Japan’s Onmyōdō 陰陽道 (Yin-Yang) circles.

Identified with Myōken in Japan. The esoteric ritual known as Anchinhō 安鎮法 (abbreviated as

Kokuchin 国鎮) was performed in the imperial palace to secure the safety of the state. The principal

deity was Fudo (Acala), and the ritual itself was one of the four great rituals of Tendai (Sanmon Shika

Daihō 山門四ケ大法). A similar ritual performed at an ordinary house was called Kachin 家鎮 or Chintaku 鎮宅

(aimed at protecting the household from calamities); hence Chintaku Reifujin’s moniker as Tutelary God of Houses.

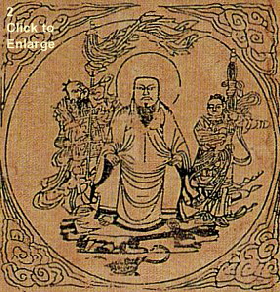

- (1) Chintaku Reifu Shin. By Shimanuki Bangetsu 嶋貫盤月. Sheet. Ink on Paper. Edo Era, 19th Century. University Art Museum, Kyoto City University of Arts. Below the deity are two attendants and Genbu 玄武 (a snake embracing a tortoise), the ancient Chinese guardian of the north. H = 60.4 cm, W = 28.8 cm.

- (2) Chintaku Reifujin. Hanging Scroll. Print on Paper. Edo Era, 19th Century. H = 111.5 cm, W = 55.5 cm.

- (3) Chintaku Reifujin. Hanging Scroll. Print on Paper. Edo Era, 19th Century. H = 111.5 cm, W = 55.5 cm.

- Photos scanned from Taoism Art Catalog. Exhibit catalog published in 2009 by the Osaka Municipal Museum of Art together with the Yomiuri Shimbun, Osaka.

Chintaku Reifujin 鎮宅霊符神. Identified with Myōken in Japan.

Also known as the “Tutelary God of Houses” in Japan’s Onmyōdō 陰陽道 (Yin-Yang) circles.

- (4) Chintaku Reifujin. Hanging Scroll. Print on Paper. Edo Era, dated 1768. H = 61.3 cm, W = 39.0 cm.

- (5) Chintaku Reifujin. Hanging Scroll. Print on Paper. Edo Era, dated 1768. H = 61.3 cm, W = 39.0 cm.

- (6) Chintaku Reifujin. Hanging Scroll. Print on Paper. Edo Era, dated 1768. H = 61.3 cm, W = 39.0 cm.

- Photos scanned from Taoism Art Catalog. Exhibit catalog published in 2009 by the Osaka Municipal Museum of Art together with the Yomiuri Shimbun, Osaka.

Hokushin Myōken Chintaku Reifujin 鎮宅霊符神. Identified with Myōken in Japan.

Also known as the “Tutelary God of Houses” in Japan’s Onmyōdō 陰陽道 (Yin-Yang) circles.

- (7) Hokushin Myōken Chintaku Reifujin. Hanging Scroll. Print on Paper. Edo Era, dated 1812. H = 88.1 cm, W = 25.4 cm.

- (8) Hokushin Myōken Chintaku Reifujin. Hanging Scroll. Print on Paper. Edo Era, dated 1812. H = 88.1 cm, W = 25.4 cm.

- Photos scanned from Taoism Art Catalog. Exhibit catalog published in 2009 by the Osaka Municipal Museum of Art together with the Yomiuri Shimbun, Osaka.

Myōken, Sun Disk, Moon Disk Myōken, Sun Disk, Moon Disk

Myōken is also associated with a red sun disk (Nichirin 日輪) and white moon disk (Gachirin 月輪), which are befitting icons symbolizing Myōken’s role as the supreme celestial deity, one “lighting” the way along the path of enlightenment. In the photo at right, Myōken’s right hand holds the sun disk with a black three-legged crow drawn inside, while the left hand holds the moon disk with a rabbit (or hare & frog) drawn inside. Even today, people purchase talismans known as the Nissei Manishu 日精摩尼手 (sun disk with 3-legged black crow) or the Gessei Manishu 月精摩尼手 (moon disk with a hare pounding rice). 摩尼は宝珠の意味. The former is purchased by those with eye disease or poor eye sight, and making proper pleas and prayers to the icon is said to cure one's eye problems. Let us recall that Myōken literally means “wonderous sight.” Making proper pleas and prayers to the moon disc is said to reduce fever and cool the body.

Three Legged Crow (Yatagarasu 八咫烏)

Like Myōken, a black crow-like bird with three legs is also closely associated with Nikkō Bosatsu (Sunlight Bodhisattva), with Emperor Jimmu 神武天皇 (Japan’s legendary first emperor), and with Nōjo Taishi 能除太子 (the founder of Haguro Shugendō).

Why the three legs and why the black crow inside a sun disk? The most plausible reasons involve Chinese mythology and Japan’s own creation myths. First, a black three-legged crow known in China as Sānzúwū 三足烏 (lit. = three-legged bird) appears in Chinese artwork dated to the Yǎngsháo 仰韶 period (5000 BC to 3000 BC). In Chinese mythology and ancient philosophical texts, this bird is intimately related to the sun. According to the Huáinánzǐ 淮南子(2nd century BC Chinese text), this bird has three legs because three is the emblem of Yang -- and the supreme essence of Yang is the sun.

Second, in Japan’s own creation myths, including the Nihon Shoki 日本書紀 (submitted to the Japanese imperial court in 720 AD), a giant crow called Yata-garasu 八咫烏 (eight-span crow) appeared to Japan’s first legendary emperor, Jimmu 神武天皇, who had landed on the shores of Japan but gotten lost. The crow was sent by Amaterasu Ōmikami 天照大神 (Japan’s supreme sun goddess) to lead Jimmu to Yamato (the heartland of Japan). Says site contributor Cate Kodo Juno, an ordained Buddhist priest of Japan's Shingon sect: “Since the crow is also associated with Myōken and the Pole Star, could it be that it was the Pole Star that guided Jimmu?”

Third, according to Maison Franco-Japonaise (which translated the film Shugen: The Autumn Peak of Haguro Shugendō): “The founder of Haguro Shugendō is Nōjo Taishi 能除太子, who is said to have come to Haguro early in the seventh century. He was given the title of Shōken Daibosatsu 照見大菩薩 in the 19th century. Legend says he was the third son of the late sixth-century emperor Sushun 崇峻天皇 (reigned 587 to 592), and the cousin of Shōtoku Taishi (574-622), Japan’s first great patron of Buddhism. According to legend, prince Nōjo renounced his title and position, took the name Kōkai 弘海, and became a wandering hermit of the mountains. Nōjo is depicted as a strange being, dark of skin and with exaggerated facial features, his mouth extending from ear to ear. It was to a place called Akoya, in a narrow valley full of thick growth, with a waterfall at one end, that Nōjo was guided by a mystical three-legged crow, and it was here that he first did ascetic training. Here also he found a statue of Kannon Bosatsu and it was from here that he founded the three sacred mountains (Dewa Sanzan) as a Shugendō site.” Site contributor Cate Kodo Juno offers another asute observation: “It is most likely that the story of Haguro Shugendō founder Nōjo Taishi is emulating the story of Emperor Jimmu, as often happens in hagiographies, in order to provide added legitimacy and authority to Nōjo’s legend.” <end quote>

Some final words on the above Shugendō legend. Today people often equate the three-legged crow with the three sacred mountains of Dewa Sanzan, but the basis of the legend clearly originated in earlier Chinese mythology. Myōken (the deification of the Pole Star and Big Dipper constellation) is a major star deity at sacred Mt. Haguro, one said to possess the power to cure eye diseases.

Rabbit (Hare) and Frog (Toad)

Myōken is also associated with a moon disk containing a rabbit and frog. Like Myōken, Gakkō Bosatsu (Moonlight Bodhisattva) is closely associated with the Gachirin 月輪 (moon disk), which depicts a rabbit pounding mochi (glutinous rice). People suffering high temperatures or fevers can purchase such talismans or icons (called Gessei Manishu 月精摩尼手), which are said to reduce fever and cool the body.

Why the rabbit? In the West, when people look at the moon, they see a man in it. The Chinese see a rabbit, pounding magical herbs to make the elixir of eternal life. The Japanese, with their love of obscure wordplay, envision the same rabbit pounding rice to make mochi. The name of the full moon is mochizuki, while mochitsuki means “making mochi.” Making proper pleas and prayers to the moon disk is said to reduce fever and cool the body. The Rabbit is also associated with the Zodiac calendar. For more on rabbit lore in China and Japan, see Gabi Greve’s site.

The frog (toad) is associated with the moon because of its bumpy skin. This creature, called Xiāmá 蝦蟆 in Chinese and Gama 蝦蟆 in Japanese, has long been associated with the moon in Chinese mythology, where it is described as large, pure white, and three legged -- with the fungus of longevity, regarded as the “branch of the soul,” growing from its head. According to many legends, it is immortal, and endowed with magical powers and sometimes even sinister qualities. For more on frog (toad) lore in China and Japan, see Animal Motifs in Asian Art: An Illustrated Guide to Their Meanings and Aesthetics by Katherine M. Ball, first published 1927, pages 173 to 181. Above clipart of the Nissei Manishu and Gessei Manishu from 日本仏像大全書 (Big Catalog of Japan's Buddhist Statues), published in Japan by 四季社 (Shikisha), 2006. ISBN4-88405-335-4 C0095.

Turtle, Tortoise, and Snake

Turtles and Snakes 亀と蛇. In artwork, Myōken is frequently shown standing atop or accompanied by a turtle, or a composite beast known as the Kida 亀蛇 (half turtle, half dragon-snake). See the numerous photos that appear herein. One of the most popular modern forms of Myōken shows the deity standing atop a turtle (the ancient Chinese guardian of the north). The turtle is one of Four Legendary Creatures (shishin 四神) guarding the four directions -- it is the emblem of the north, as is Myōken. The tortoise is the hero of many old legends. It helped the first Chinese emperor to tame the Yellow River, and in return was rewarded with a life span of ten thousand years. Thus the tortoise became associated with longevity, as are rituals involving Myōken (see Sonjō-ō Mandala above). In both Chinese and Japanese artwork, a common symbol for longevity is a snake embracing a tortoise (Genbu 玄武; see photo at right), for Chinese mythology says their union engendered the universe (there were no male tortoises -- as the ancients believed --- so the female had to mate with a snake). In China, the tortoise-snake pairing dates back to the third century AD. Grave steles, memorial stones, and reliquaries placed atop tortoise effigies can still be found in China and Japan, and were reserved for only the highest ranking members of the imperial family or ruling class. In Japan, extant artwork linking the turtle with the seven stars of the Big Dipper can be traced back to the early 8th century. In the two images in the right column, we see a sketch of the legendary tortoise that appeared before Japan’s emperor in 715 AD, with the seven stars of the Big Dipper engraved on its shell. Below that we see the actual piece in the collection of the Shōsō-in 正倉院 in Nara. Made of Serpentine rock (Jyamongan 蛇紋岩). The appearance of this terrapin is recorded in the Shoku Nihongi 続日本紀 (compiled around +797) in book six. Enter search term “turtle” at this site to read story. Photo sources narahaku.go.jp and ameblo.jp.

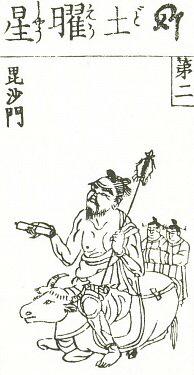

Eagle 鷲 (Washi or Otori)

During Japan’s Edo period (1603 to 1868), a curious form of Myōken appeared depicting the deity atop an eagle (see photo at right). This deity is said to be a manifestation of Hagunshō 破軍星, the 7th star of the Big Dipper, and one identified with the Zodiac sign of the horse. As mentioned earlier, Myōken is worshipped in some quarters as the guardian of horses (and hence, the patron of warriors and farmers, who relied upon horses in both warfare and agriculture). This version of Myōken is associated with the Edo-era temple-shrine multiplex of Jūzaisan Chōkokuji Temple 鷲在山長国寺 and Washi (Eagle) Shrine 鷲神社 in Tokyo's Asakusa district. The multiplex was divided during the forced separation of the Buddha-Kami in the early Meiji period, with Myōken (atop an eagle) moving to Chōkokuji Temple, while Washi (Eagle) Jinja became dedicated to Amenohiwashi 天日鷲 and Yamato-Takeru-no-Mikoto 日本武尊 (Brave Warrior of Yamato) -- the latter is associated with a large white bird. Washi Jinja is today popularly known as "Otori Sama" and is considered the pre-eminent Tori 酉 (bird) shrine in Japan. This former temple-shrine multiplex is credited with creating the still-popular Tori no Ichi 酉の市 (Rooster Day Festival), held annually in November on the Zodiac day of the rooster, during which people come to pray for health, good fortune, and business success. Colorful and decorative kumade 熊手 (rakes) are sold by venders in the shrine and temple compounds -- kumade are especially prized by merchants, who believe the objects have the power to rake in good fortune. Says the temple’s official E-site: “The temple of Chōkoku-ji was established in 1630, in the early years of the Edo period, and it was dedicated to Nichiren, the Buddhist priest who founded the sect that is named after him. Enshrined in the temple is a statue of Washi Myōken Bodhisattva (see above image), who holds a sword in the right hand and has an aureole incorporating the seven stars of the Great Bear constellation. Familiarly known as Otori-sama among the people of Edo (now Tokyo), the statue stands on the back of an eagle (washi), hence its name, and it is reputed to bring good fortune and prosperity to all people who worship it.” The temple’s crests are called Moon Crests or Big Dipper Crests.

Myōken Resources & References Myōken Resources & References

- Zuzōshō: Esoteric Iconography of Myōken Bosatsu. The Zuzōshō (Zuzosho) 図像抄, or the Encyclopedia of Buddhist Icons, was edited by Ejū 恵什 (1060-1145). Says the Japan Society: ”The earliest surviving images that can be definitely identified as Myōken Bosatsu appear in the Zuzōshō, the ten volume esoteric iconographic manual compiled c.1135. The section entitled "Myōken Bosatsu" begins with a text that describes the characteristics of the deity, Sanskrit mantra (magic spells), and ritual procedures. In art, this deity’s head is often surrounded by the nimbus of the seven celestial sages (of the Big Dipper). The deity often rides a peculiar beast composed of an intertwined serpent and turtle (the guardian of the north), which represents the world in total, longevity, and health. MYŌKEN is a warrior and is traditionally appealed to on the eve of battle.” <end quote by Japan Society, “Myoken Bosatsu: The Adoption & Adaptation of the Pole Star Deity by Samurai and Townspeople in Pre-modern Japan.”>

-

The Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice. Edited by Lucia Dolce. Special double issue of Culture and Cosmos. ISSN 1368-6534. See especially story by scholar Gaynor Sekimori entitled "Star Rituals and Nikkō Shugendō," pages 217-250. The Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice. Edited by Lucia Dolce. Special double issue of Culture and Cosmos. ISSN 1368-6534. See especially story by scholar Gaynor Sekimori entitled "Star Rituals and Nikkō Shugendō," pages 217-250.

- Mt. Haguro 羽黒山. The three deities of sacred Mt. Haguro (and the Haguro Shugendo sect) are (1) Myōken Bosatsu, the deification of the Pole Star and the Dipper constellation; (2) Gundari Myō-ō, who represents the six marker stars of the south; and (3) the central divinity Kannon Bosatsu.

- Myōken is mentioned in the Ryōjin Hishō 梁塵秘抄 (Treasured Selections of Superb Songs), which was compiled personally by Emperor Goshirakawa 後白河上皇 (1127-93) and released in 1179. It is the largest extant collection of Japanese songs that flourished between the mid-Heian to the early Kamakura period. Myōken was worshiped at that time mainly for the power to cure eye diseases.

- Taosim Art 道教の美術. Exhibit catalog published in 2009 by the Osaka Municipal Museum of Art together with the Yomiuri Shimbun, Osaka. Fabulous exhibit with approx. 420 Tao-related art works. The exhibit was held first in Tokyo, then Osaka and Nagasaki, between late 2009 and early 2010. A brilliant catalog. Various photos above and below were scanned from this catalog.

Myōken-zan Kokuseki-ji Temple 妙見山 黒石寺. Founded in +729 by Monk Gyōki 行基 as Tokozan Yakushi-ji Temple 東光山薬師寺 of the Tendai 天台 sect and renamed Myōkenzan Kokuseki-ji Temple in +849. The temple is famous for its Kokuseki-ji Sominsai Fire Festival, held on the evening of January 7th until the next morning. Myōken-zan Kokuseki-ji Temple 妙見山 黒石寺. Founded in +729 by Monk Gyōki 行基 as Tokozan Yakushi-ji Temple 東光山薬師寺 of the Tendai 天台 sect and renamed Myōkenzan Kokuseki-ji Temple in +849. The temple is famous for its Kokuseki-ji Sominsai Fire Festival, held on the evening of January 7th until the next morning.

- Myōkensai 妙見祭.

The Myōken Festival at Yatsushiro Shrine 八代神社 (aka Myōkengū 妙見宮)in Yatsushiro City 八代市 (Kumamoto Prefecture 熊本県) is held annually for two days on Nov. 22-23. This lively festival involves a parade featuring a six-meter-long turtle with a two-meter-long snake head that is carried around town. This half-snake half-turtle is called a Kida 亀蛇. See numerous photos of the festival at this J-site.

- Like Myōken, the deity Marishiten is sometimes represented as a female with eight arms, two of which are holding aloft the sun disc and moon disc, and worshipped as a guardian of the nation and warriors. Marishiten is addressed as 天后 queen of heaven, or as 斗姥 (literally “mother of the Southern Measure μλρστζ or Sagittarī), and associated thus with the constellation of Sagittarius and the seven stars of the Little Bear (Little Dipper), which perhaps explains why s/he (Marishiten) drives a chariot drawn by seven pigs. See Marishiten page for details.

- Online Resources about Myōken

- Online resources about Chintaku Reifujin

- Japanese book about this deity Chintaku Reifujin; Kannō Himitsu Shūhōshū, by Kenjun Yamagishi. worldcat.org/title/chintaku-reifujin-kanno-himitsu-shuhoshu/oclc/028352195

鎮宅霊符神; 感應秘密修法集

- 鎮宅霊符神教 大阪 Major sect that worships this deity in Osaka today.

土御門神社(陰陽道)の「鎮宅霊符神」

裟竭龍王 Sagara (Shakara, Shakatsura-ryuo, Sha-gara-ryuo)