|

|

|

|

The Shichifukujin 七福神 are an eclectic group of deities from Japan, India, and China. Only one is native to Japan (Ebisu) and Japan’s indigenous Shintō tradition. Three are deva from India’s Hindu pantheon (Benzaiten, Bishamonten, Daikokuten) and three are gods from China’s Taoist-Buddhist traditions (Fukurokuju, Hotei, Jurōjin). In my mind, it is more fruitful to explore the seven within a Deva-Buddha-Kami (Hindu-Buddhist-Shintō) matrix rather than a standard binary Buddha-Kami model. For that reason, I have devoted most of my research to the three Hindu deva. Today images of the seven appear with great frequency in Japan. In one popular Japanese tradition, they travel together on their treasure ship (Takarabune 宝船) and visit human ports on New Year’s Eve to dispense happiness to believers. Children are told to place a picture of this ship (or of Baku, the nightmare eater) under their pillows on the evening of January first. Local custom says if they have a good dream that night, they will be lucky for the whole year. Each deity existed independently before Japan’s “artificial” creation of the group. The origin of the group is unclear, although most scholars point to the Muromachi era (1392-1568) and the late 15th century. By the 19th century, most major cities had developed special pilgrimage circuits for the seven. These pilgrimages remain well trodden in contemporary times, but many people now use cars, buses, and trains to move between the sites. The group’s seven members have varied over time and did not become standardized until the late 17th century. In the beginning, Benzaiten was not a member of the ensemble. One later configuration included both Kichijōten and Benzaiten, but excluded Fukurokuju. Today the standard group consists of Ebisu, Daikokuten, Bishamonten, Benzaiten, Hotei, Jurōjin, and Fukurokuju. This INTRO PAGE provides a brief history of the group. For full textual reviews and photos of any single deity, click that deity’s name. Why the number seven? Details here.

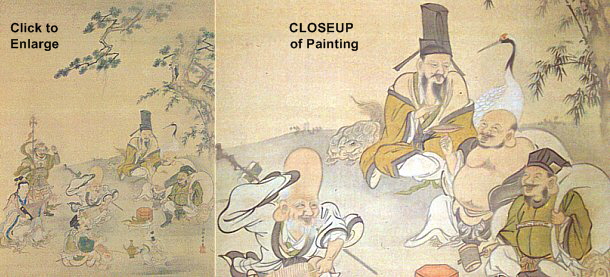

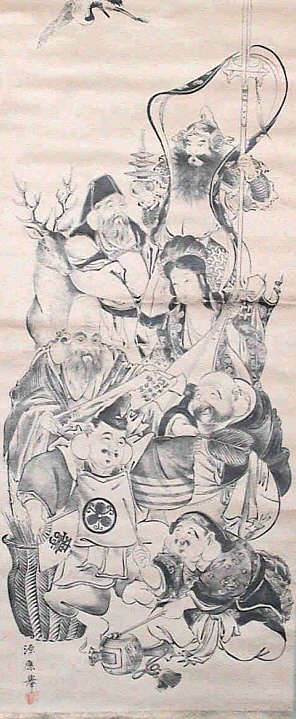

Earliest extant pictorial example of all seven in the standard set.

Seven Gods of Good Fortune, the standard set, by Kano Yasunobu 狩野安信 (1613-1685). Hanging scroll,

ink and colors on silk, H = 139 cm, W = 97.4 cm. University Art Museum, Tokyo National University of Fine

Arts and Music. Above photos from art historian Patricia Graham.

Writes Graham in Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art (1600-2005), page 112: “This example [above photo] by Kano Yasunobu is considered the earliest extant pictorial example of the theme, though his brother Tan’yu probably portrayed them together first. The official rank used by Yasunobu in his signature (Hōgen) helps date the painting to between 1662, when Yasunobu received this honorary title, and his death in 1685. The artist has placed the figures in an outdoor setting, beneath a pine tree, dressed in the attire of the upper classes and engaged in a lively drinking party in which participants play musical instruments, dance and sing. The composition so resembles that used by academic Ming dynasty painters in their portrayal of the Eight Daoist Immortals that such pictures, known to have been imported to Japan in the Edo period, must be considered their prototype.” <end quote>

|

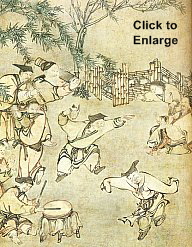

ABOVE & BELOW

Seven Sages in a Bamboo Grove (Chikurin Shichiken 竹林七賢)

Hanging Scroll, Ink & Color on Paper

H = 102.6 cm, W = 51.8 cm

16th century. Photo from Tokyo Nat’l

Museum Exhibition Catalog entitled

“A Selection of Japanese Art from the

Mary & Jackson Burke Collection”

May 21 - June 30, 1985

|

|

ORIGINATED IN LATE 15TH CENTURY ORIGINATED IN LATE 15TH CENTURY

Says JAANUS: ”These seven auspicious deities are first believed to have been grouped together and given the name ‘shichifuku’ during the Muromachi period. At first, the group’s members were not fixed and Benzaiten became one of the seven somewhat later. The group of seven may derive from the Chinese subject of Seven Sages in a Bamboo Grove 竹林七賢 (Chn. = Zhú Lín Qī Xián; Jp. = Chikurin Shichiken) of the Wei and Jin Period 220-420 AD or from a famous Buddhist term in the 8th-century Ninnōgyō Sutra 仁王経 given therein as ‘Shichinan Sokumetsu Shichifuku Sokushō 七難即滅 七福即生 (lit. = seven adversities disappeared and seven fortunes arose).’ From the 15th century, the Shichifukujin gained in popularity, especially among urban merchants and artisans, as an auspicious omen and motif of good fortune and longevity, and appear in many painted, sculpted and printed examples.”

Adds scholar Patricia Graham, in Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art (1600-2005), page 110: “The earliest references to some abbreviated assemblage of two, three, or even five of these deities date to late 15th-century texts about popular narrative tales (otogi zōshi) and comic Nō plays (kyōgen) and also mention lost paintings of them. Probably only in the second half of the seventeenth century did the conception of a set of seven deities of good fortune coalesce. But even then, the set had not become universally standardized.”

One of the oldest extant drawings of an abbreviated assemblage of the group.

Five of the Gods of Fortune 五福神図, by Kanō Tanyū 狩野探幽 (1602-1674).

Ebisu (fish), Daikokuten (rice bale), Bishamonten (spear), Benzaiten (biwa), Hotei (big bag & fan). Photo from this J-site.

I’m not sure, but I think this piece is at the University Art Museum, Tokyo National University of Fine Arts & Music.

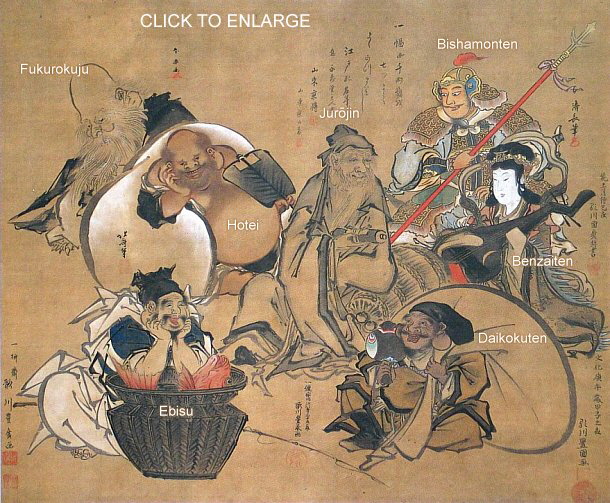

Seven Gods of Good Fortune, the standard set, early 19th century.

Collaborative painting by Hokusai Katsushika 葛飾北斎 (1760-1849),

Utagawa Kunisada 歌川 国貞 (1786-1865), Utagawa Toyokuni 豊国 (1769-1825),

Torii Kiyonaga 鳥居清長 (1752-1815), and others. The image of Hotei holding

huge white bag by Hokusai Katsushika. Photo from this J-site.

17TH CENTURY & SEVEN VIRTUES

Says the Flammarion Iconographic Guide <pp. 239 -238>: “This popular group of deities recalls ’the seven wise men of the bamboo thicket’ or the ‘seven wise men of the wine cup’ whose images are popular in China. [The Japanese group] was artificially created in the 17th century by the monk Tenkai 天海 (who died in 1643 and was posthumously named Jigen Daishi 慈眼大師), who wanted to symbolize the essential virtues of the man of his time for the Shōgun Tokugawa Iemitsu 徳川家光 (1623-1650 AD).”

However, art historian Patricia Graham, p. 112 says: “Twentieth-century sources credit the priest Tenkai, Ieyasu’s advisor, with concocting the grouping for the edification of the third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu. These sources explain that Tenkai identified the individual gods with seven virtues (longevity, fortune, popularity, candor, amiability, dignity, magnanimity) that kings impart to their subjects if they [the kings] follow the teachings of the Sutra of the Benevolent Kings (Ninnō-kyō 仁王經). However, Tenkai’s known writings and Rinnōji Temple 輪王寺 records make no mention of the Seven Gods.” See below table for deity-virtue identifications.

Seven Gods of Good Fortune, by Hakuin Ekaku 白隠慧鶴 (1685–1768),

Hanging Scroll, ink and colors on paper, H = 57.8 cm, W = 89.4 cm,

Photo from Gitter-Yelen Collection, New Orleans

Writes art historian Patricia Graham in Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art (1600-2005), page 115: “Here [above photo], Hakuin took artistic license and modified the familiar group of the Seven Gods, replacing Bishamonten with Shōki, a mythical Chinese demon queller and arbiter of Buddhist hells. As here, Shōki is always shown as an imposing, bearded figure wearing the robes of a Chinese scholar official. Hakuin probably thought to include Shōki in the group because by then he had also come to be considered a household protector, and people hung pictures of him in homes, especially during the Boys’ Day festival season in the fifth month.” <end quote>

LOCAL TRADITIONS

On New Year’s Eve, the seven enter port together on their Takarabune 宝船 (treasure ship) to bring happiness to everyone. On the night between Jan. 1 and 2, tradition says, children should put, under their pillow, a picture of the seven aboard their treasure ship, or a picture of the mythological Baku (eater of nightmares). If you have a lucky dream that night, you will be lucky for the whole year, but you must not tell anyone about your dream -- if you do, you forfeit its power. If you have a bad dream, you should pray to BAKU 獏 or set your picture adrift in the river or sea to forestall bad luck <Sources: Chiba Reiko, Kodo Matsunami, and JAANUS.>

|

Drawing of the Treasure Boat.

Kanji in sail says TREASURE 宝.

Kōyaji Temple 高野寺, Takeo City 武雄市,

Saga Pref. Photo this J-Site.

|

|

TREASURE BOAT TREASURE BOAT

The treasure ship (Takarabune 宝船) is laden with treasure (Takara 宝). Says JAANUS: “The Chinese character BAKU 獏, a Chinese imaginary animal thought to devour (i.e. prevent) nightmares, is sometimes found written on the sail. Often auspicious cranes and tortoises are depicted in the sky and the sea. Although the origin of treasure-boat paintings is not clear, one Edo-period record indicates that they were started in the Muromachi period.”

- Hat of Invisibility = Kakuregasa 隠れ笠, and Cloak of Invisibility (Lucky Raincoat) = Kakuremino 隠れ蓑. Allows one to perform good deeds without being seen.

- Robe of Feathers = Hagoromo 羽衣. A long loose flowing garment giving one the gift of flight. Attribute of Benzaiten.

- Magic Mallet, Mallet of Good Fortune = Uchide no Kozuchi 打出の小槌. Brings forth money when struck against an object or when shaken. Common attribute of Daikokuten.

- Bag of Fortune = Nunobukuro 布袋 (lit. cloth bag). Includes an inexhaustible cache of treasures, including food and drink. Common attribute of Hotei.

- Never-Empty Purse or Moneybag = Kanabukuro 金袋. Bag of unlimited wealth, prosperity & fortune.

- Key to Divine Treasure House = Kagi 鍵. The treasure house is symbolized by the stupa (pagoda) held by Bishamonten.

- Rolls of Brocade = Orimono 織物. Scarves and clothing were considered treasures in ancient times and used in various rituals. Not sure of its meaning here.

- Scrolls of Wisdom & Longevity = Makimono 巻物. Common attributes of Jurōjin and Fukurokuju, who are said to be two different manifestations of a single deity (the god of wisdom and longevity).

- More details in Chiba Reiko’s book (pp. 9-12).

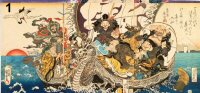

Votive Tablet (EMA 絵馬) from Enoshima Jinja 江島神社 (Enoshima Shrine). Modern.

Shows the Seven Lucky Gods on their dragon-headed treasure ship. The dragon is a symbol of

treasure and a protector of both shrines and temples. Auspicious and long-lived cranes appear in the sky.

The character 寶 (treasure of buddha-nature) is drawn inside the mast. The large red characters are pronounced

Kaiun Shōfuku 開運招福, which means "Inviting Good Luck, Fortune and Prosperity." Enoshima Shrine is one the Three Great Benzaiten Sanctuaries (Nihon Sandai Benten 日本三大弁天) in Japan -- hence the characters 日本三大弁天 appear as well.

Edo-period (1603 to 1868) painting of the seven on their dragon-headed boat. Wood, 180 cm X 100 cm.

This painting served as the “model” for many subsequent paintings of the seven, as shown below.

It also depicts the luck-bringing crane, Mount Fuji, and the red-rising sun. Photo from this this J-site (location not given).

1. Reproduction. Modern. Click to enlarge. Photo from this this J-site.,

2. Reproduction. Modern. Click to enlarge. Photo from this this J-site.,

3. Reproduction. Modern. Click to enlarge. Photo from this this J-site.,

Redistributing Wealth -- Earthquakes as the Great Equalizer

Seven Lucky Gods Riding a "Namazu" Treasure Boat. Entitled 繁昌たから船, Late 19th Century.

On New Year's Eve, the seven enter port together on their Takarabune 宝船 (treasure ship) to bring happiness

to everyone. The boat is typically shaped like a dragon, but in this print it is shaped like a catfish (namazu).

Namazu is a giant catfish thought to live deep inside the earth. Its movements are said to cause earthquakes.

The seven are dressed in the garb of laborers who stand to gain from earthquake devastation, e.g. carpenters,

construction workers, fire fighters, roofers, harlots, tile merchants, and plasterers. The ocean itself is represented

by roof tiles, while the namuza is subdued by a mast-supporting wooden pole.

A lucky crane, turtle and dragon appear as well. Photo this this J-site.

|

Quakes create both winners and losers, have and have nots, survivors and victims, those who gain from the devastation and those who suffer from it. Earthquakes are therefore sometimes portrayed as a dreaded-yet-needed ways to renew the corrupted world, to redress social imbalances, to destroy the greed of the rich, and to restore Japanese society and its economy to normality (yonaoshi 世直し or "world rectification"). Phrased differently, earthquakes help to redistribute wealth. Says Gregory Smits (in a classroom presentation): "Earthquakes are bad news for those killed and seriously injured, as well as for those who lose homes and jobs. Following the 1855 Ansei Earthquake, however, many of Edo's common people profited handsomely from the rebuilding. All of the construction trades as well as porters, many types of vendors, sellers of raw material like lumber, and others -- probably a majority of Edo's ordinary people -- profited from the earthquake. Big losers included most social elites, especially the very wealthy, who had to pay sky-high prices to have their mansions rebuilt. It was as if the earthquake was an attempt by the cosmic forces to redistribute the wealth that had been accumulating among the big merchants and other social elites. Indeed, many of the catfish picture prints regarded the earthquake as strong social medicine -- with the unfortunate side effect of killing several thousand people." <end quote>

|

|

PILGRIMAGES TO THE SEVEN LUCKY GODS

By the 19th century, most major cities had developed special pilgrimage circuits for the seven. These pilgrimages remain well trodden in contemporary times, especially during the first three days of January. But today, many people use cars, buses, and trains to move between the sites rather than walking. To document their journey, some pilgrims purchase a rectangular stamping sheet at their first location -- called a Kinen Shikishi 記念色紙 -- then present it to each successive temple or shrine for stamping. An example of a fully stamped kinen shikishi is shown below.

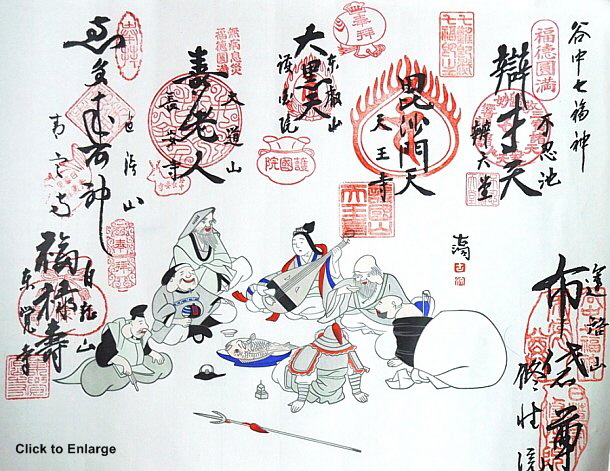

Stamping sheet from the Yanaka Shichifukujin Meguri 谷中七福神巡り or

“Pilgrimage to the Seven Lucky Gods in Tokyo's Yanaka district.” The Yanaka pilgrimage is

reportedly the oldest circuit devoted to the seven in Japan. Photo courtesy this J-site.

ABOVE ILLUSTATION. Modern-day poster (2008). Found at Myōryūji Temple 妙隆寺 in Kamakura. The temple also sells this image as a shikishi 色紙 (colored sheet of paper used for calligraphic poems or paintings). Myōryūji Temple is the seventh site on the Kamakura Pilgrimage to the Seven Lucky Gods. It honors Jurōjin. To document your pilgrimage, buy a rectangular stamping sheet, called a kinen-shikishi 記念色紙. You buy this at your first destination (1,000 yen), then at each successive stop in the circuit of seven, hand it to the temple office for stamping.

RUBBING TRADITION RUBBING TRADITION

Another equally curious tradition still widely practiced in Japan is that of rubbing Daikoku or Hotei. When visiting temples that enshrine statues of the seven deities, visitors often rub the head / shoulders of Daikoku (the god of wealth and business prosperity). Doing so is said to bring wealth - which rubs off the statue onto the rubber. Photo at right shows life-size wooden Daikoku statue at Hase Dera in Kamakura -- the sign at his feet says “Rubbing Daikoku -- Please Touch” Also, rubbing the stomach of Hotei is said to bring good luck.

|

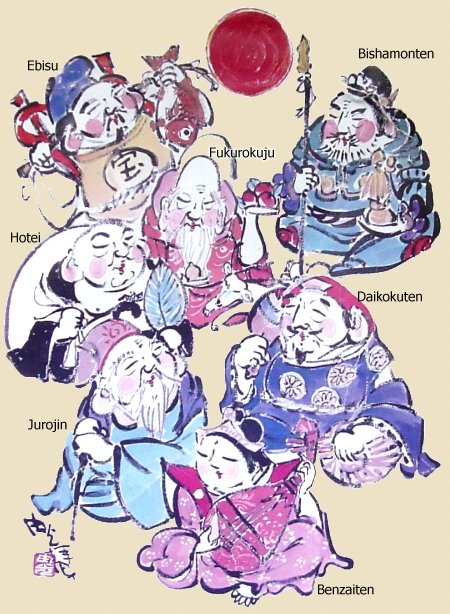

QUICK OVERVIEW OF THE SEVEN

plus others who once served in this role

|

|

Name & Origin

|

Function

|

Associations

|

|

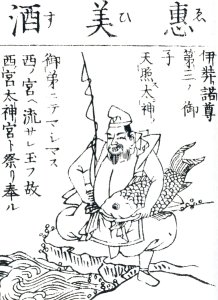

Ebisu 恵比須

Origin = Japan.

Shinto Name: Kotoshiro-nushi-no-kami

|

God of the Ocean, Fishing Folk, Good Forture, Honest Labor, Commerce. Virtue = Candor, Fair Dealing

|

Holds a fish (TAI, sea bream or red snapper), which symbolizes luck and congratulation (Japanese word for happy occasion is omede-TAI); fishing rod in right hand; folding fan in other; grants success to people in their chosen occupations; son of Daikoku. Popular among fishing folk, sailors, and people in the food industry.

|

|

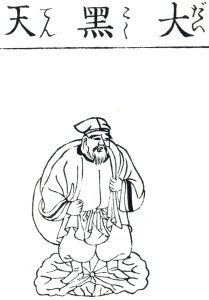

Daikokuten 大黒天

Origin = India.

Skt. = Mahakala

Intro to Japan 9th C. AD

|

God of Earth, Agrculture, Farmers, Wealth, Prosperity, Flood Control, The Kitchen. Virtue = Fortune

|

God of five cereals; rice bales; treasure sack (bag); magic mallet in right hand; sometimes wears hood; rat (found around food); often shown with Ebisu, who is said to be his son; merged with Shinto deity of good harvests, Okuninushi no Mikoto. Also a member of the TENBU. Popular among farmers, agricultural businesses, & traders.

|

|

Benzaiten 弁財天

Origin = India.

Skt. = Sarasvati

|

Goddess of Music, Beauty, Eloquence, Literature, Art. Virtue = Amiability

|

Japanese mandolin, lute, magic jewel, snake, sea dragon. Only female among the seven. Member of the TENBU grouping. Popular among artists, musicians, and writers.

|

|

Hotei 布袋

Origin = China.

Chn. = Putai, Budai

Chinese Sage.

Budaishi (Jp. = Fuudaishiten)

|

God of Contentment and Happiness. Virtue = Magnanimity

|

Bag of food and treasure that never empties; oogi (fan), small children at his feet; supposedly only member of seven based on actual person (although Jurōjin / Fukurokuju might also be based on real person); known as the Laughing Buddha; rubbing his stomach is said to bring good luck; incarnation of Bodhisattva Maitreya (Jp. = Miroku). Popular among bartenders and all classes of people. Best known of the seven outside Japan.

|

|

Fukurokuju 福禄寿

Origin = China.

Taoist Hermit Sage

|

God of Wealth, Happiness, Longevity, Verility, and Fertility. Virtue = Popularity

|

Huge elongated head; long white beard, cane with sutra scroll, crane, deer, stag, tortoise (symbols of longevity); scroll said to contain all the wisdom in the world; said to inhabit same body as Jurōjin (the pair are two different manifestations of the same deity); wields power to revive the dead. Popular among watchmakers, athletes, others.

|

|

Jurōjin 寿老人

Origin = China. Identified with Laozi (Jp. = Rōjinseishi), the founder of Chinese Toaism

|

God of Wisdom & Longevity. Virtue = Longevity.

Also spelled Jurojin.

|

Long white beard, knobbly staff with scoll of life attached; tortoise, deer, stag, crane; in same body as Fukurokuju (the pair represent two different manifestations of the same deity); scroll said to hold the secret to longevity; sometimes carries a drinking vessel, as he reportedly loves rice wine (sake). Popular among teachers, professors, and scientists.

|

|

Bishamonten 毘沙門天

Origin = India.

Skt. Vaisravana.

|

God of Treasure, Bringer of Wealth, Defender of the Nation, Scourge of Evil Doers, Healer of Ilness. Virtue = Dignity

|

Wears armor, carries spear and treasure pagoda; centipede is messenger; Vaisravana in Sanskrit; also known as Tamonten (the commander of the Shitenno or Four Heavenly Kings), and a member of the TENBU Popular among soldiers, doctors, and certain Buddhist monestaries; the only member of the Shitenno worshipped independently.

|

|

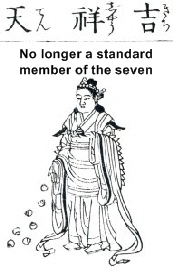

Kichijōten 吉祥天

Origin = India.

Skt. Mahāśrī, Mahasri, Lakṣmī, Laksmi

|

Goddess of fortune, luck, beauty, and merit. From the 8th century onward, she was a central devotional deity among some Japanese sects, and was given individual cult status as an object of Buddhist worship. But since the 15th / 16th century, her imagery and attributes were largely supplanted by the Goddess Benzaiten (Benzaiten is now the only female among Japan’s Seven Lucky Deities). Kichijōten appeared as one of the seven lucky deities in the 1783 Zōho Shoshū Butsuzō-zui 増補諸宗仏像図彙 (see images below), but since then she has been dropped from the group.

|

|

Shōjō 猩猩

Origin = Japan

|

A nonstandard member of the group, Shōjō (a sea-dwelling sea sprite, fond of drinking, and hence typically colored red) appeared in the 1690 Butsuzō zu 仏像図彙 (Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images; see images below), but has since been dropped. For more details, please see Gabi Greve’s page.

|

|

Marishiten 摩利支天

Origin = India

Also Santen 三天

Lit. = Three Deities

Marishiten

Daikokuten

Benzaiten

|

In Japan, there is another goddess/god (of Hindu origin) named Marishiten. Introduced to Japan in the early 9th century, s/he is revered as a tutelary deity of the warrior class. In her female form, she is the consort of Dainichi Nyorai (Skt. = Vairocana), the Great Solar Buddha. In this role, she is the harbinger of Dainichi, the Goddess of Dawn, a personification of light, one identified with the blinding rays & fire of the rising sun, and thus with the power of invisibility and mirage. In later centuries, she was worshipped as a goddess of wealth and prosperity among merchants and gamblers (most likely for her powers of illusion). S/he was counted along with Daikokuten 大黒天 and Benzaiten 弁財天 as one of a trio of "three deities" (Santen 三天) invoked for good fortune during the Edo era. Marishiten has been largely supplanted by Benzaiten.

|

|

Sanmen Daikoku

三面大黒天

Origin = Japan

|

In Japan’s Muromachi Era (1392-1568), an esoteric three-headed form of Daikokuten emerged that combined the head’s of Daikokuten, Benzaiten, and Bishamonten. All three are members of the Seven Lucky Gods. This 3-headed version of Daikokuten is is believed to protect the Three Buddhist Treasures (the Buddha, the law, and the community of followers). This iconography is very similar to another kitchen deity named Kōjin-sama. As the three-headed deity, Sanmen Daikoku awards followers with wealth and virtue.

|

|

Important Note: The member’s of the Seven Lucky Gods have varied over time. In the beginning, Benzaiten was not a member of the group. One later grouping included both Kichijōten and Benzaiten, but excluded Fukurokuju. In modern Japan, the group nearly always consists of Ebisu, Daikokuten, Bishamonten, Benzaiten, Hotei, Jurōjin, and Fukurokuju.

|

|

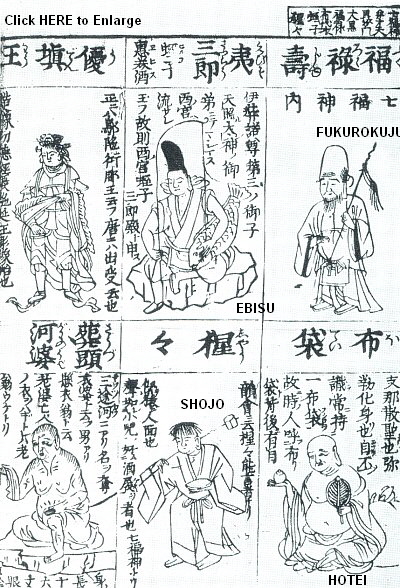

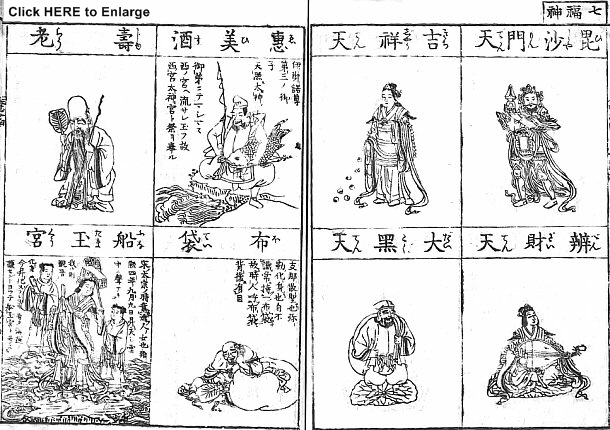

IMAGES OF SEVEN GODS FROM THE BUTSUZŌ-ZU-I

Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙 (Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images) was first published in 1690 (Genroku 元禄 3) and has since become a major authority on Japanese Buddhist iconography. Hundreds of pages and drawings, with deities classified into approximately 80 (eighty) categories.

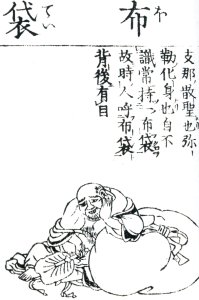

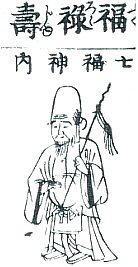

From the 1690 Butsuzō zui 仏像図彙 (Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images).

Source: Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library.

The original 1690 version does not include the seven deities we know today, but instead a slightly different version that excludes Jurōjin and includes the nonstandard Shōjō 猩猩 (a sea-dwelling sea sprite, fond of drinking, and hence typically colored red). The expanded 1783 version excludes Fukurokuju, who is said to inhabit the same body as Jurōjin. Instead, in his place, we find Kichijōten, goddess of fortune, luck, beauty, and merit. Among some Japanese sects, she was the central devotional deity, given individual status as an object of Buddhist worship, but since the 15th / 16th century, her imagery and attributes have been largely supplanted by the Goddess Benzaiten (now the only female among Japan’s Seven Lucky Deities). Let us again quote from art historian Patricia Graham (Faith and Power, page 110): “In the 1690 version, only Fukurokuju, Hotei, Ebisu, and the nonstandard member of the group, Shōjō 猩猩, a sea-dwelling, red-haired, and perennially jovial monkey-faced figure from Japanese mythology, are pictured. Bishamonten, Benzaiten, and six different forms of Daikokuten are found in the preceding pages of the book, and Jurōjin is found not at all.” She then explains that the enlarged and revised 1783 version of the Butsuzō zui by Tosa Hidenobu contained the codified set of seven (see image below). She writes: “The presence of the Seven Gods in the revised edition indicates that by 1783 the assemblage had become part of mainstream Buddhism.” <end quote>

1796 reprint of the 1783 Zōho Shoshū Butsuzō-zui 増補諸宗仏像図彙. Fukurokuju is missing, replaced by Kichijōten

(Enlarged Edition Encompassing Various Sects of the Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images)

BELOW -- Click any image to jump to individual deity page

|

|

Benzaiten (1783)

Sole Female, Hindu-Buddhist Pantheon

|

Bishamonten (1783)

Hindu-Buddhist Pantheon

|

Daikokuten (1783)

Hindu-Buddhist Pantheon

|

|

Ebisu (1783)

Sole Japanese Deity

|

TODAY’S

STANDARDIZED SET

Benzaiten

Bishamonten

Bishamonten

Ebisu

Fukurokuju

Hotei

Jurōjin

Images from the 1690

Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙 or

from the enlarged 1783 version

|

Kichijōten (1783)

Female, Hindu-Buddhist Pantheon

|

|

Hotei (1783)

Buddhist Pantheon China

|

Fukurokuju (1690)

Taoist Pantheon China

|

Jurōjin (1783)

Taoist Pantheon China

|

|

|

|

|

|

Seven Gods of Good Fortune by Hokusai Katsushika 葛飾北斎 (1760-1849).

Photo this J-site. Photo also at this J-site and also here.

Seven God of Fortune, artist unknown.

Perhaps by Maruyama Ōkyo 円山応挙 (1733-1795). Photo this J-site.

Seven Gods of Fortune (1882) by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka 芳年月岡 (1839-1892).

Here we see the seven indulging in drunken revelry. Photo this J-site.

|

|

|

|

|

|

WHY THE NUMBER SEVEN ?

|

|

The Shichifukujin are an excellent example of the way Hindu, Buddhist, and Shinto beliefs live side by side in Japan, influencing one another, and even lending each other gods !

Shichinan Shichifuku Zukan

七難七福図巻 Handscroll of Seven Adversities & Seven Fortunes, 1768.

39 meters long, by Maruyama Ōkyo

円山応挙 (1733-1795).

Shōkoku-ji Temple Jōtenkaku Museum

相国寺承天閣美術館 in Kyoto.

Photo Kyoto Shimbun.

|

|

The Japanese people appear bewitched by the number seven -- much like the rest of the world. The West, for example, had its seven wonders of the world. Rome, it is said, was built on seven hills. Medieval Christians counted seven deadly sins. In the age of discovery, explorers traveled the seven seas. The modern world revolves around a seven-day week. People still say they are ”in seventh heaven" when they are extremely happy (a phrase that originated in Dante’s The Divine Comedy). This obsession with number seven no doubt reflects the visibility of the seven-star Big Dipper and the seven planets (Sun for Sunday, Moon for Monday, Mars for Tuesday, Mercury for Wednesday, Jupiter for Thursday, Venus for Friday, Saturn for Saturday). The Japanese people appear bewitched by the number seven -- much like the rest of the world. The West, for example, had its seven wonders of the world. Rome, it is said, was built on seven hills. Medieval Christians counted seven deadly sins. In the age of discovery, explorers traveled the seven seas. The modern world revolves around a seven-day week. People still say they are ”in seventh heaven" when they are extremely happy (a phrase that originated in Dante’s The Divine Comedy). This obsession with number seven no doubt reflects the visibility of the seven-star Big Dipper and the seven planets (Sun for Sunday, Moon for Monday, Mars for Tuesday, Mercury for Wednesday, Jupiter for Thursday, Venus for Friday, Saturn for Saturday).

The mystery of number seven has enraptured the Japanese as well. Ancient Japan was founded around seven districts. In Japanese folklore, there are seven Buddhist treasures and seven deities of good luck (the topic of this story). Japanese Buddhists believe people are reincarnated only seven times, and seven weeks of mourning are prescribed following death. The list goes on and on -- the seven ups and eight downs of life, the seven autumn flowers, the seven spring herbs, the seven types of red pepper, the seven transformations, and the popular 7-5-3 festival held each November for children, in which special Shinto rites are performed to formally welcome girls (age 3) and boys (age 5) into the community. Girls (age 7) are welcomed into womanhood and allowed to wear the obi (decorative sash worn with kimono).

MORE ABOUT NUMBER SEVEN

Scholar John Dougill also points out that the number seven is prominent in Japanese verse: “What interests me are the origins of the 5-7-5-7-7 syllable pattern of short verse (tanka). As this was later adapted to the 5-7-5 of haiku, it’s a hallmark of Japanese poetry. Since Chinese influence was prevalent in Japan after the sixth and seventh centuries, the likelihood is that the 5-7 syllable pattern arose from Taoist numerology and the inclination to see odd numbers as favouring ki vitality and energy flows.” <end quote> In this context, we should add that Chinese cosmology considers odd numbers as auspicious. The Japanese adopted the same preference, as reflected in their stone pagodas (always with an odd number of stories, i.e. 5, 7, 9, 13). This preference for odd numbers is also reflected in Japan’s major festivals -- which are still held on odd days. This is known in Japan as Gosekku 五節句 (lit. = five seasonal festivals), as listed below:

- First month, first day = Kochōhai 小朝拝, New Year Celebration, together with the seventh day after the New Year known as Jinjitsu 人日 or Nanakusa no sekku 七草の節句 (feast of seven herbs).

- Third month, third day = Kyokusui no en 曲水の宴, Drinking Around a Rolling Stream.

- Fifth month, fifth day = Tango no sekku 端午の節句 or Boys’ Festival.

- Seventh month, seventh day = Kikkouden 乞功奠 or Tanabata 七夕 Festival.

- Ninth month, ninth day = Chōyō no en 重陽の宴 or Feast of Chrysanthemums.

Over the centuries several of the festivals changed dates or names. For example, when Japan adopted the solar calendar in 1872, the feast of seven herbs was moved from the 7th of the lunar calendar to the 7th day of January. In addition, the third month festival became the Hinamatsuri 雛祭 or Doll Festival. We should also mention that, in the lunar calendar, the new moon (1st of the month), the half-moon of the first quarter (7th or 8th), the full moon (15th), and the half-moon of the last-quarter (22nd or 23rd), are considered sacred days and known as Hare-no-hi 晴れの日. All other days of the months are known as Ke-no-hi 褻の日. Until modern times, Japan's most important festivals were almost always held on Hare-no-hi days. See Zodiac Calendar page for more details. In addition, star worship may have played a role in the 5-7 syllable pattern of Japanese poetry. The five planets (each linked to one of the five elements), along with the sun and moon, are known as the seven celestial bodies (Shichiyō 七曜). Each is associated with a specific deity, day of the week, and compass direction. The seven stars of the Big Dipper have likewise been deified. See planets and stars page for more details.

|

|

SOURCES

- Butsuzō zui 仏像図彙 (Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images). Published in 1690 (Genroku 元禄 3). A major Japanese dictionary of Buddhist iconography. Hundreds of black-and-white drawings, with deities classified into categories based on function and attributes. For an extant copy from 1690, visit the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library. An expanded version, known as the Zōho Shoshū Butsuzō-zui 増補諸宗仏像図彙 (Enlarged Edition Encompassing Various Sects of the Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images), was published in 1783. View a digitized version (1796 reprint of the 1783 edition) at the Ehime University Library. Modern-day reprints of the expanded 1886 Meiji-era version, with commentary by Ito Takemi (b. 1927), are also available at this online store (J-site). In addition, see Buddhist Iconography in the Butsuzō-zui of Hidenobu (1783 enlarged version), translated into English by Anita Khanna, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 2010.

- Graham, Patricia. Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art (1600-2005), pages 109-115. World-class scholarship concerning Japan’s religious history & icons. University of Hawai’i Press, 2007.

- Handbook on Viewing Buddhist Statues 仏像の見方ハンドブック. By Ishii Ayako. A wonderful book. Published 1998. Japanese Language Only. 192 pages; 80 or so color photos. ISBN 4-262-15695-8.

- JAANUS. Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. A wonderful online dictionary compiled by the late Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent. It covers both Buddhist and Shinto deities in great detail. Over 8,000 entries. Written in English, yet presenting all key terms in Japanese.

- Buddhism (Flammarion Iconographic Guides)

, by Louis Frederic, Printed in France, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. A highly illustrated volume, with special significance to those studying Japanese Buddhist iconography. Includes many of the myths and legends of mainland Asia as well, but its special strength is in its coverage of the Japanese tradition. Hundreds of accompanying images/photos, both B&W and color. , by Louis Frederic, Printed in France, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. A highly illustrated volume, with special significance to those studying Japanese Buddhist iconography. Includes many of the myths and legends of mainland Asia as well, but its special strength is in its coverage of the Japanese tradition. Hundreds of accompanying images/photos, both B&W and color.

- Essentials of Buddhist Images: A Comprehensive Guide to Sculpture, Painting, and Symbolism. By Kodo Matsunami. Paperback; first English edition March 2005; published by Omega-Com. Matsunami (born 1933) is a Jōdo-sect 浄土 monk, a professor at Ueno Gakuen University, and chairperson of the Japan Buddhist Federation. He received the government's Medal of Honor (褒章 hōshō), Blue Ribbon, for his achievements in public service. Says Matsunami: “Bishamonten protects from disaster and bodily harm. Daikoku satisfies the desire for food. Benzaiten represents sexual desire. Hotei brings laughter, and Ebisu grants wealth.

- Tobifudo Deity Dictionary. Ryūkozan Shōbō-in Temple 龍光山正寶院 (Tokyo). Tendai Sect.

- The Seven Lucky Gods of Japan

, by Chiba Reiko. Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1966. Also see UCLA Center for East Asian Studies, Educational Resources from teacher Samantha Wohl, Palms Middle School, Summer 2000. See Wohl’s Materials List (based on Chiba Reiko’s book). , by Chiba Reiko. Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1966. Also see UCLA Center for East Asian Studies, Educational Resources from teacher Samantha Wohl, Palms Middle School, Summer 2000. See Wohl’s Materials List (based on Chiba Reiko’s book).

LEARN MORE

- Buy statues of the Seven Lucky Gods from our Sister Site

- Pilgrimage to the Seven Lucky Gods in Kamakura (this site)

- Story by Kevin Short / Special to Yomiuri Shimbun (this site)

- Ivory Set of the Seven Luckies (missing Ebisu) (this site)

- Number Seven (Seiyaku.com) and Seven Lucky Gods in Tokyo

- Pilgrimage to the Seven Lucky Gods in Tokyo

- Seven Sages in a Bamboo Grove

- Seven Sages at the Cleveland Museum of Art (Chinese artist Fu Baoshi 1904-1965)

- Seven Sages Painting by Chinese Artist Ou Hao-nian (b. 1935 -)

- Google Image Search for the Seven Sages

- Seven Sages, 400 CE stone rubbing, China

- Seven Sages, 400 CE stone rubbing, China (J-Site)

- Seven Sages, 400 CE, stone rubbing, China

- Seven Sages, 400 CE, stone rubbing, China (C-site)

- Gabi Greve’s pages on talismans and amulets from Japanese temples and shrines,

plus regional folk toys, folk art, handicrafts, and folklore.

Click here for hundreds of modern Japanese cartoons of the Seven Lucky Gods

Modern netsuke of the seven. Visit our Seven Lucky Gods eStore to purchase online.

|

|