|

|

|

|

|

Dōsojin 道陸神, also known as

Sae no Kami or Sai no Kami

障の神・塞の神・道祖神

Jō-to-Uba 尉と媼, the happy couple

Stone, 1749, Gunma Prefecture, Nakanojōmachi 中之条町馬滑

Photo this J-site.

Jō-to-Uba 尉と媼

The happy couple

Dōsojin at Izu Hantō 伊豆半島

Photo by Gabi Greve

Dōsojin along Kinubariyama

Hiking Course in Kamakura

Stone, Late 20th century.

Photo by Schumacher.

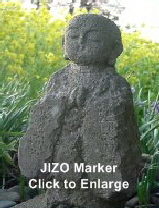

Jizo Bosatsu, stone, modern.

Protector along Kamakura’s

Kinubariyama hiking course

Photo by Schumacher.

Six Jizō (Roku Jizō) Intersection.

Kamakura. Early 20th century. Stone.

Decked in red bibs and caps, these six watch over the safety of travelers at

a busy intersection in Kamakura city.

Photo by Schumacher.

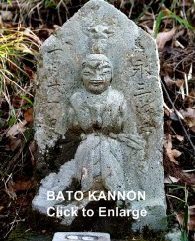

Batō Kannon, Stone, 1850

Fujino Township, Magino District

Photo by Norman Havens

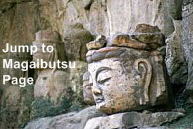

12th-century stone carvings

in Ōita Prefecture. See video.

Click here for dōsojin slideshow

Stone, Buddha Triad

Sansonzou 三尊像, H = 115.4 cm

Ishiidera 石位寺 (Nara)

Late 7th Century

Photo by Ogawa-Kouzou

Photo tour at this J-site

Photo tour at this J-site

Photo tour at this J-site

|

|

DŌSOJIN 道祖神 (Dōsojin, Dousojin) DŌSOJIN 道祖神 (Dōsojin, Dousojin)

PROTECTIVE STONE MARKERS

BOTH SHINTŌ & BUDDHIST

Dōsojin literally means “road ancestor kami”

The Shintō Tradition

Dōsojin refers to Shintō deities of roads and borders. Also called Dōrokujin 道陸神 and Sae no Kami or Sai no Kami 障の神・塞の神・道祖神 (with “sae / sai” meaning to obstruct or keep out the evil spirits). These deities reside in stone markers found at village boundaries, in mountain passes, and along country byways. In urban areas today, dōsojin stone markers are often placed at street corners and near bridges to protect pedestrians. As the deity of the village border, the dōsojin wards off evil spirits and catastrophes, and protects the village from evil outside influences. As deity of the road, the dōsojin protects travelers, pilgrims, and those in "transitional" stages. These stone markers may bear only inscriptions, but often they depict human forms, in particular the images of a man and woman -- the latter manifestation is revered as the kami (deity) of marriage and fertility. In some localities, the dōsojin is worshiped as the kami of easy childbirth.

Says site contributor Dr. Gabi Greve: “The Takasago Legend 高砂伝説 is one of the oldest in Japanese mythology. An old couple -- his name is Jō 尉 and her name is Uba 媼 -- known together as Jō-to-Uba 尉と媼, are said to appear from the mist at Lake Takasago. The old man and his wife are usually portrayed talking happily together with a pine tree in the background. Signifying, as they do, a couple living in perfect harmony until they grow old together, they have long been a symbol of the happiness of family life. The story is portrayed in a famous Nō play called "Takasago no Uta." <end quote> For many more details, please visit Gabi Greve’s page.

Japan's popular Fire Festivals, held around January 15 each year, are known as dōsojin festivals. Shrine decorations, talismans, and other shrine ornaments used during the local New-Year holiday are gathered together and burned in bonfires. They are typically pilled onto bamboo, tree branches, and straw, and set on fire to wish for good health and a rich harvest in the coming year. The practice of burning shrine decorations has many names, including Sai-no-Kami Matsuri 道祖神祭, Sagichō 左義長, Seikisūhai 性器崇拝 and Dondo Yaki どんど焼. According to some, the crackling sound of the burning bamboo tells the listener whether the year will be lucky or not. Children throw their calligraphy into the bonfires -- and if it flies high into the sky, it means they will become good at calligraphy.

The Buddhist Tradition

The origin of dōsojin stone markers is shrouded in the mists of uncertainty, and no exact date can be given. But precedents are ample in the Buddhist world (see links below for some wonderful photo tours). Here again we meet one of Japan's most popular and beloved deities, Jizō Bosatsu. In the early centuries following the introduction of Buddhism to India (introduced around 500 BC), Jizō became known as the guardian of travelers and pilgrims, and statues of his image could be found along pilgrimage routes and mountain passes in India and Southeast Asia. That tradition is still evident in modern Japan, where one often finds groupings of six Jizō statues standing guard on the high roads or at busy intersections. (Note: The six Jizō correspond to the Six States of Karmic Rebirth in Buddhist traditions). Among the many trails zigzagging the foothills of Kamakura (where I live), one can also find solitary figures of Jizō guarding the way. Nationwide, one can find stone statues in almost every corner -- statues honoring a bewildering number of different Buddhist deities (see links below).

Japan has for centuries venerated its local crossroad deities (guardians of the road known as dōsojin and sae no kami). These deities protect the village against evil influences while standing guard over graveyards, execution grounds and other liminal areas. These crossroad deities are synonymous with Japan’s old phallic stones, which were erected at village boundaries to guarantee the fertility of the land and its communities. In my mind, Jizō’s assimilation with the local dōsojin and sae no kami is one of the main reasons for his longstanding appeal in Japan.

Elsewhere in Japan, one can still find many stone statues of Batō Kannon (Kannon with Horse’s Head) -- this is especially true in northern Japan. These statues are set up along dangerous paths and byways to protect travelers and their horses from injury (see photo at right and visit the Batō Kannon page for more details). Stone markers with Buddhist associations are called sekibutsu 石仏 in Japan (details below).

Says Norman Havens: “A recent survey has reported that Fujino Township (Kanagawa Prefecture) has over 800 stone buddhas, images of kami, and similar memorial stelae throughout the area. During the pre-modern periods, Buddhist precepts prevented the Japanese from eating four-legged mammals, and when a horse or ox died after a lifetime of work, it was frequently memorialized with a stele. As the one here shows, the practice continued into the modern period.” <end quote by Norman Havens>

Sekibutsu 石仏

Stone Carvings of Buddhist Deities

Courtesy of JAANUS (excellent dictionary of Buddhist concepts). Sekibutsu literally means “Stone Buddha.” A Buddhist image made in rock or stone. The term sekizou 石造 or "carving from stone" was used to indicate the material of a sculptured work. Sekibutsu were divided broadly into two groups:

- Magaibutsu 磨崖仏

Buddhist images carved on large rock outcrops, cliffs, or in caves. Caves carved with Buddhist images which were large enough for people to enter and used as temples were specifically called sekkutsu jiin 石窟寺院 (cave temple).

Famous examples of Magaibutsu include those in Usuki 臼杵 (Ooita prefecture; 11c-12c; see above photo), Ooya 大谷 (Tochigi prefecture.; 11c-12c), Izumisawa 泉沢 (Fukushima prefecture) as well as the Fudou 不動 at Nissekiji 日石寺 (Toyama prefecture.; 12c). It is speculated that stone statues suddenly became popular because their durable quality suited the mood of the "end of the world" belief (mappou shisou 末法思想) prevalent in the 10th to early11c.

The 13c production of sekibutsu once again focused sculpture production on much smaller-scale works, and with the exception of the group stone carvings at Hakone 箱根 (Kanagawa prefecture.) no magaibutsu carvings were produced. However, numerous, small-scale free-standing stone statues related to regional popular faith, such as Jizou 地蔵, Shoumen Kongou 青面金剛, or local Shinto deities (see Shintou Bijutsu 神道美術), were produced and placed at the outskirts of a village to ward off evil and sickness. Many such statues can still be seen today on roadsides. For much more on Magaibutsu and Sekibutsu, please see the Big Buddha page.

- Free-Standing Sekibutsu 石仏

A free-standing, movable statue carved from stone. Carving a work from a single block of stone was called isseki-zukuri 一石造. Sometimes a single figure or group statue was carved out of a single block of stone, but sometimes several blocks were joined. Stone was the chief material used for Buddhist images in China and India, whilst in Japan stone statues have never challenged the dominance of wood and bronze because appropriate stone materials were not so readily available. Neverthless, examples dating from the 7c on can be found over a very wide area of the country. Mainly soft rocks such as tuff (consolidated volcanic ash) and tufa (porous calcium carbonate rock) were used until the 12c, but thereafter hard rocks such as granite came to be used.

The oldest known sekibutsu 石仏 (stone sculpture) in Japan is the Buddha Triad (Sansonzou 三尊像) at Ishiidera 石位寺 Temple (Nara ; late 7th century). The main deity and two attendants were carved from a single chunk of stone in intermediate elief (hannikubori 半肉彫). Another well-known example is the 8th century bodhisattva group called Zutou 頭塔 (Nara), which depicts 13 figures carved in low relief (usunikubori 薄肉彫)on one stone block. There are a few other examples dating from the 9th century in the Nara area, and after the 10th century large-scale rock and cliff carvings were produced over a very wide area of Japan. <above paragraph adapted from JAANUS>

- Please also visit the Stones Top Menu for an overview of other stone markers and memorials. Also see Magaibutsu (Buddhist images carved on cliffs), and Sekibutsu (free-standing Buddhist images carved in stone). These latter types of stone sculptures are found nationwide, although over half are located in Kyushu, the earliest inhabited area of Japan and the main door to the Japanese islands during the country’s earliest contact with the cultures of mainland Asia.

LEARN MOR E

- Big Buddha Statues in Japan

Learn much more about large and small stone carvings of the Buddhist deities, with special sections on the Magaibutsu (Buddhist images carved on large rock outcrops, cliffs, or in caves) and Sekibutsu (free-standing, movable statues carved from stone).

- Ishidoro. Japanese stone lanterns.

- Gorinto, Gravestones, Memorial Markers. Includes details on Buddhist stone markers for funerals, and for demarcating sacred spots and memorial purposes. This includes steles, pagodas, and stupas, often in memory of deceased people.

- Dōsojin Photo Tour #1

This Japanese-language site is a treasure house of photos of stone markers in Japan. Although written in Japanese, the images talk louder and are easy to select. Highly recommended. Outstanding selection of photos.

http://blowinthewind.net/asekibutu.htm

http://blowinthewind.net/plngallery/vol07/idx.htm

- Dōsojin Photo Tour #2

Japanese-language site with many photos of stone markers, organized into useful categories (sorry, Japanese language only). Easy to navigate. Dozens of photo tours. Highly recommended. Excellent photos.

http://www1.kcn.ne.jp/~yosikatu/dousogin1.htm

http://www1.kcn.ne.jp/~yosikatu/index.html

- Dōsojin Photo Tours (More)

1. homepage2.nifty.com/koba843/photo/photo14a.htm

Click the pink 次ページ button to scroll through pictures.

2. www.geocities.co.jp/SilkRoad-Ocean/8937/html/setumei_frame.htm

Click the left-column links.

3. Gabi Greve’s page (also see Daruma dolls)

- Below Dōsojin text courtesy:

http://teishoin.sakura.ne.jp/sekibutu/kaie.html

Guardian deity of roads and village boundaries, worshiped in the form of stone images along the roadside. Also known as sae no kami, an ancient designation that suggests the function of 'obstructing' or 'keeping out' sae (evil spirits). The dōsojin is often identified with the god Sarutahiko, who guided Ninigino-mikoto, the supposed ancestor of the imperial line, on his descent to earth. The object of workship takes various physical forms. Today, dōsojin function also as gods of marriage(You can see a couple of gods), birth, and other rituals. They are widely feted throughout Japan during the burning of the New Year's ornaments dondo-yaki on 14 and 15 January. Children in some regions go door-to-door to solicit rice cakes or other offerings 'for the dōsojin', and they eat it. In this region, dondo-yaki is on 14 January, at Tenmangu shrine next to Teishoin.

- OTHERS. Other stone markers include protector deities like the Shishi (magical lions who stand guard outside the gates at Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines), the Tanuki, a raccoon-like magical dog found outside bars and business shops, and the Maneki Neko (beckoning cat) found outside restaurants.

- RELATED TERMS

Jishin 地神. God who protects rice plants and brings about abundant rice crops. Farming folk venerate the Jishin deity, who is typically equated with Ta-no-kami 田の神 (deity of the rice paddy) and Yama-no-kami 山の神 (deity of the mountain). In early spring, Yama-no-kami descends from the mountains to become Ta-no-kami. After the rice harvest, the kami returns to the mountains to become Yama-no-kami.

|

|