|

|

|

|

SHŌKI 鍾馗 - THE DEMON QUELLER

Protector Against Evil Spirits & Illness

Expels the Demons of Plague

Guardian -- Safety of Hearth & Home

Protects Homes with Male Children

Protects Male Heirs to the Chinese Throne

Origin = China

Chinese Name = Zhōng Kuí, Chung Kuei, Chung K’uei, Chung Kwei

Japanese spellings: Shōki, Shoki, Shouki, Shooki

UPDATE: Aug. 2, 2010

An original ink painting of SHŌKI by Kitagawa Utamaro (1754-1806),

last seen in 1975, has been rediscovered in a private home in Japan.

Stone Statue, Taishō Era (1912-1925),

in garden of site author, Kamakura.

Shōki 鍾馗 is a deity from China’s Taoist pantheon who was depicted often in Edo-period (1615-1868) Japanese sculptures and paintings, but one who is today largely neglected. Legends about Shōki reportedly first appear in Tang-era (618-907) Chinese documents. The deity reached Japan by at least the late Heian Period (794 to 1185), for the oldest extant image of Shōki in Japan is a scroll at the Nara National Museum dated to the reign of Emperor Goshirakawa 後白河天皇 (1127-1192). Numerous legends surround Shōki in Japan and the West. The three most widespread are:

- Shōki is the Chinese deity who protected Tang-era Emperor Xuanzong 玄宗 (Jp: Gensō, 685-762) from malevolent demons. According to this legend, Shōki appeared to the sick emperor in a dream and subdued the demons causing his sickness. In gratitude, the emperor awarded Shōki the title of "Doctor of Zhongnanshan" (Jp. = Shūnanzan-no-Shinshi 終南山の進士). By the way, Zhongnanshan 終南山 is the legendary birthplace of Chinese Taosim. It is here that Taoism's founder, Laozi 老子 (Jp. = Rōshi) reportedly gave classes and wrote the Taoist classic "Tao Te Ching." The sacred terrace monastery is called Louguantai 楼観台. <Sources: Tokyo National Museum, JAANUS, and The Art Institute of Chicago>

- Shōki wanted, above all else, to serve as a physician in the imperial palace, but when he failed the national exam he committed suicide in despair. Emperor Xuanzong heard this story, and in pity, posthumously awarded Shōki the title "Doctor of Zhongnanshan." Shōki’s spirit thereafter vowed to protect the emperor and empire from evil. <Source: JAANUS>

- Shōki was a Tang-era physician in the Chinese province of Shensi, but he was very ugly. To advance his career, he took the national examination to enter imperial service, and performed brilliantly, scoring first place among all applicants. But when Shōki was presented to the emperor, he was rejected because of his ugliness, and in shame, Shōki committed suicide. Overcome with remorse, the emperor ordered Shōki to be buried in the green robe reserved for the imperial clan. In gratitude, Shōki's spirit vowed to protect the ruler and all male heirs from demons of illness and evil. <Source: Minneapolis Institute of Art>

- Says Hugo Munsterberg in his Dictionary of Chinese and Japanese Art: “In China, he is canonized with the title of ‘Great Spiritual Chaser of Demons.’ He is usually represented in art as a large ugly man, wearing a scholar’s hat, a green robe and large boots, and is usually shown either stabbing or trampling on demons.”

Shōki’s popularity peaked in Japan during the Edo period, when people began to hang images of Shōki outside their houses to ward off evil spirits during the Boys' Day festival (Tango no Sekku 端午の節句, May 5 each year, but now a festival for all children of both sexes) and to adorn the eaves and entrances of their homes with ceramic statues of the deity. Today, Shōki is a minor deity relatively neglected or forgotten by most Japanese, except perhaps in Kyoto city, where residents still adorn the eaves and rooftops of their homes with Shōki’s effigy to ward off evil and illness, and to protect the male heir to the family.

|

Rediscovered Painting of Shōki

by Kitagawa Utamaro 喜多川歌麿 (1754-1806)

|

|

|

Shoki, the Demon Queller

Scroll-mounted ink drawing on paper.

H = 81 cm, W = 27.5 cm

Original brush painting by

Kitagawa Utamaro 喜多川歌麿 (1754-1806).

Photo: Mainichi Daily News (Aug. 2, 2010)

|

|

Says Gina Collia-Suzuki's Floating Along in the World of Japanese Prints: “Two original brush paintings by Kitagawa Utamaro, last seen at an exhibition in 1975, have been rediscovered in a private home in Tochigi, Japan.” Above closeup photo from Gina Collia-Suzuki.

Says the Mainichi Daily News (Aug. 2, 2010): “Two original prints by legendary Edo-period artist Utamaro Kitagawa, which had not been located for nearly 35 years, have been found at the home of an elderly family in Tochigi, city officials announced.” Above scroll image from Mainichi.

|

|

Below Text Courtesy of JAANUS

A god in the Chinese Taoist pantheon known as the "Demon Queller," often depicted in sculpture and painting. A devoted but flawed student, Zhongkui failed the national examination and in despair committed suicide. When Emperor Xuanzong 玄宗 (Jp: Gensō, 685-762) heard of this extreme act he had the degree and title "Doctor of Zhongnanshan" (Jp: Shūnanzan-no-Shinshi 終南山の進士) posthumously bestowed on Zhongkui. In return, the ghost of Zhongkui appeared to Xuanzong in a dream and promised to protect the empire from evil demons. Another version holds that when the Emperor was ill Zhongkui appeared in a dream and killed the demons who had plagued the Emperor, and in gratitude Xuanzong awarded Zhongkui the title. Pictures of Zhongkui were hung in homes to protect or rid them from demons especially at the Boy's Festival on May 5, and the practice of placing a small statuette of Zhongkui under the eaves of a house survives in Japan. In paintings Zhongkui is usually shown with large eyes, a bushy beard, and wearing black robes and an official's cap. He is often depicted drawing a large sword or using it in battle with demons. Records mention images of Zhongkui from the Tang period, but a painting attributed to the Northern Song artist Li Gonglin 李公麟 (Jp: Ri Kōrin, 1049?-1106) seems to be the earliest extant image. In Japan, of the countless paintings of Zhongkui, those by Yamada Dōan 山田道安 (fl.16c, Enkakuji 円覚寺, Kanagawa Prefecture), Kanō Tan'yū 狩野探幽 (1602-74), Watanabe Kazan 渡辺華山 (1793-1841) and Tanomura Chikuden 田能村竹田 (1777-1853) are well known. <end JAANUS quote>

Shōki - painting by artist Sesson Shukei 雪村周継 (1504-1589)

Photo Courtesy Kyoto National Museum

|

Portion of scroll showing Shōki

Late Heian Period, H = 25.9 cm, W = 45.2 cm

Photo Tokyo National Museum.

The scroll, however, is a treasure

of the Nara National Museum.

|

|

Below Text & Photo Courtesy Below Text & Photo Courtesy

of the Tokyo National Museum

The Exorcists Scroll. All the deities shown here are considered, in China, to be benevolent deities who expel the “demons of plague.” This set was originally mounted as a handscroll that was known as the "second edition of the Masuda family Hell Scroll." After the war, the handscroll was cut into sections and the paintings mounted as hanging scrolls. The acts of each of the gods in exterminating evil are briefly explained in the texts accompanying the illustrations.

A Buddhist tale (J. setsuwa) relates that Shōki, a demon-quelling deity from China, protected the Tang emperor Xuanzong (685-762) from malevolent demons. He is portrayed with large eyes and a thick beard and is wearing a black robe, hat, and tall boots. Here, he is shown strangling a small demon. This scroll, called the Extermination of Evil (Hekija-e 辟邪絵) or Exorcists Scroll, is conjectured to have been made during the time of Emperor Goshirakawa 後白河天皇 (1127-1192) in the latter part of the Heian period (794-1185) and kept in the treasure house of Rengeo-in Temple (Sanjūsangendō). <end TNM quote>

Below text from Minneapolis Institute of Art Below text from Minneapolis Institute of Art

According to Japanese folklore, the spirit of the physician Shōki is able to scare away demons. Families with male children even today hang images of Shōki outside their houses to ward off evil spirits during the Boys' Day festival (Tango no Sekku, May 5 each year, but now a festival for all children of both sexes).

Who is Shōki ? During the early T'ang Dynasty, Shōki was a physician in the province of Shensi, China. He was considered very ugly. Hoping to advance his career, he took the examinations required to enter government service. Although he performed brilliantly, Shōki's dreams of advancement were shattered. Some say Shōki was cruelly cheated out of first place. Others say he was awarded first place by the examiners, who praised his work, saying it was equal to that of the wisest ancients.

But when Shōki was presented to the court, the emperor rejected him because he was so ugly. In shame, Shōki took his own life on the steps of the imperial palace, right in front of the emperor. Overcome with remorse, the emperor ordered that Shōki be buried with the highest honors, wrapped in a green robe usually reserved for members of the imperial clan. In gratitude, Shōki's spirit vowed to protect any ruler against the evil of demons. <This is essentially the same legend as reported by Hugo Munsterberg in Dictionary of Chinese & Japanese Art.>

This popular story of Shōki was adopted from China, where he was known as Chung Kuei. During the Edo Period in Japan (1600-1868), families began to hang banners depicting Shōki inside and outside of their houses during the Boys' Day festival. Boys' Day is celebrated on the fifth day of the fifth month of the lunar year. According to ancient tradition, this is a day when evil spirits and bad luck abounds. Images of Shōki ward off danger from the homes of families with male children. <end quote Minneapolis Institute of Art>

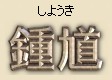

Shōki the Demon Slayer - Print by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka 月岡芳年 (1839-92)

Photo Minneapolis Institute of Art. Also see Ukiyo-e Museum - Nagoya TV Server

Shōki -- Closeup of Woodblock Print, Bijin-ga, Pre-1920

Photo courtesy of Ichiban Japanese Antiques. On sale at www.fareastasianart.com

|

Ivory Netsuke, Shōki & Oni (demon), Hidemasa, 19th century

Photo www.netsuke-inro

|

Shōki - Ivory Netsuke

18th century (oni on head)

Photo Sloan's Auctioneers

& Appraisers

|

Shōki - Ivory Netsuke

Photo http://sell-antique.com

|

|

|

Shōki glaring over the eaves of a town house

KYOTO Internet Magazine/ City of Kyoto, 1997

|

|

Says Kyoto Internet Magazine:

Eyes wide open, a small earthenware image of the Taoistic immortal, Shōki-san, glares out into space from the roof of a house. Facing the street from above the eaves of Kyoto's town houses, Shōki-san is as intense in these modern times as ever. This legendary character is said to have appeared in a dream of the Tang emperor, Xuan Zung, and brought him back to health by expelling the devil of illness.

Therefore, Shōki-san stands above the eaves, receiving prayers from the house occupants for safety in the home and protection from illness. Shōki-san is easily recognized by his heavy beard and the short sword in his right hand, while the hems of his garments are forever trailing in the wind. There is something strange about those wide, glaring eyes. A closer examination suggests a facial expression that is not without humour. Is there anything more one could ask for in a deity protecting our homes? <end text from Kyoto Internet Magazine>

Shōki on Rooftop, Photos courtesy Mark T. Hacala

Director, Education Institute U.S. Navy Memorial Foundation, Washington, DC

Writes Mark Hacala: “I wanted to offer you my understanding of the Shōki statues. They sit over the doors of a great many homes and buildings in Kyoto. Each year I have my students play "spot the Shōki" as we move through the city. A Kyoto cabbie informed my counterpart that some people also place them in their homes above their stoves. In either case, he suggested that Shōki was supposed to be a protector against fire as well as a general-purpose guardian deity.” <end quote from Mark Hacala, April 2004>

Shōki figure, often found above entrances to Japanese homes

Photo courtesy of ha7.seikyou.ne.jp/home/hatt/ (J site)

For 10 more photos, visit: ha7.seikyou.ne.jp/home/hatt/satuei-note.htm

BELOW TEXT

Source Unknown (No longer online).

Likely from Minneapolis Institute of Art

|

Demon-Queller Zhong Kui)

Circa 1745, woodblock print, ink on paper (sumizuri-e) with hand-coloring; urushi-e; pillar print (hashira-e); John Chandler Bancroft Collection, 1901.1201.

Photo: worcesterart.org

|

|

Background. When Buddhism was introduced to Japan in the 6th century, the Japanese also imported many other aspects of Chinese culture, including Chinese mythology. The popular story of Shōki was adopted from China, where he was known as Chung Kuei. During the Edo period in Japan (1600-1868), families began to hang banners depicting Shōki inside and outside of their houses during the Boys' Day festival. Boys' Day is celebrated on the fifth day of the fifth month of the lunar year. According to tradition, this is a day when evil spirits and bad luck abounds. Images of Shōki ward off danger from the homes of families with male children. Background. When Buddhism was introduced to Japan in the 6th century, the Japanese also imported many other aspects of Chinese culture, including Chinese mythology. The popular story of Shōki was adopted from China, where he was known as Chung Kuei. During the Edo period in Japan (1600-1868), families began to hang banners depicting Shōki inside and outside of their houses during the Boys' Day festival. Boys' Day is celebrated on the fifth day of the fifth month of the lunar year. According to tradition, this is a day when evil spirits and bad luck abounds. Images of Shōki ward off danger from the homes of families with male children.

Rising Merchant Class. During Japan's Edo period, great cities and a new, prosperous merchant class flourished. Middle-class tastes were significantly different from those of the Buddhist priests and shogunate (the government under a shogun) that had dominated artistic patronage in the past. Members of the new middle class preferred scenes of everyday life and illustrations of folk stories like Shōki the Demon Queller. By the 18th century many artists depicted Shōki in prints for this new audience.

Prints. As a result of this new patronage and the development of a many-colored woodblock printing process, an abundance of printed materials were made available to all. Novels, pictures, and poetry helped inform the Japanese of their own cultural heritage as well artistic styles and themes imported from China. For commoners who could not afford a painting, these new prints offered an affordable alternative.

The long narrow format of PILLAR PRINTS, achieved by pasting together two sheets of paper, was popular and practical. Whereas most prints were pasted into albums, pillar prints were hung in the home. The traditional Japanese house had very few walls, and the sliding doors that divided the rooms were made of paper. Structural wooden pillars were the only place where pictures could be hung.

Masanobu. The artist Okumura Masanobu 奥村政信 (1686-1764) invented the popular pillar print format. He was one of Japan's most important painters and printmakers during the 18th century. By his own account, Masanobu was responsible for dozens of technical and stylistic innovations in printmaking. <See photo at top of this web page for painting by Okumura Masanobu.>

Shōki, the Demon Queller. Shōki typically appears as a portly bewhiskered man. He wears scholar's robes, a hat, and heavy knee-high boots and carries a large sword. His large eyes, bulbous nose, and fierce expression are also characteristic features. In this print Shōki rounds a corner in hot pursuit of a demon. His eyes bulge out as he spies his prey. His left hand tenses, while his right reaches for his long broad sword.

Masanobu deftly varies his use of line to convey mood, texture, and mass. The thick, wavy, jagged outlines of Shōki's drapery capture his intense vitality. The fine delicate lines of his wild windblown beard and hair contrast the thicker lines of his bushy eyebrows and mustache. Masanobu uses dramatic shading in light and dark to emphasize the bulk of the figure. Masanobu creatively uses this narrow vertical format to enhance his storytelling. Shōki does not fill the length of the print, but is relegated instead to the lower two-thirds. This position emphasizes his short and portly stature. By cropping from view much of Shōki's arms, one leg, and the ends of his hair and beard, Masanobu gives the impression of catching a quick glimpse of the elusive demon queller.

The characters (the SYMBOLS used in the Japanese writing system) placed in the lower left corner of this pillar print of Shōki, are the artist Masanobu's studio name, Hogetsudo, and his signature, Okumura Bunkaku Masanobu.

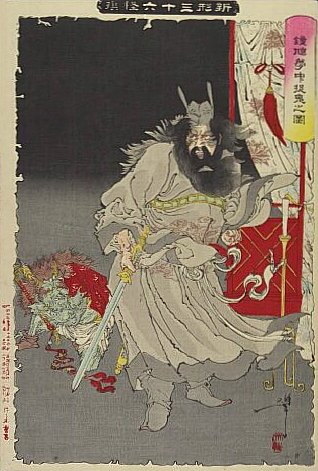

Shōki the Demon Queller, Carrying Two Baskets Filled with Demons

Attributed to Kitagawa Hidemaro 喜多川秀麿

Early 19th century, Woodblock Print, Sumizuri-e

Photo Minneapolis Institute of Art

|

Zhong Kui 钟馗 (also spelled Zhong Kui, Zhong Kwei, Chung Kuei)

Ink Painting (78 cm by 78 cm) by contemporary Chinese artist Xi Ding 西丁.

Acquired from the son of Xi Ding by P. M. Patings (Lelystad, Netherlands) in May 1992 in Xiang, China.

Photo courtesy of Patings, who runs the Tsubo-en Zen Garden Online Guidebook and Tsubo-en Diary.

The Chinese text (from right to left) reads as follows: Portrait painting of Zhong Kui 钟馗图. After the death of the first emperor of the T'ang dynasty (618 – 907), the roaming spirit of the deceased emperor caused the second emperor Xuan Zhong 玄宗 (Le Long Ji; 685-762) to have nightmares with many demons in them. Determined to get rid of this, Xuan Zhong summoned, after he had awaked from a bad dream, the then famous painter Wu Daozhi and ordered him, based on the appearances in his dreams, to make a painting of Zhong Kui, the guardian against evil demons. Thereafter and into the Song dynasty, representations of Zhong Kui became much beloved by the people. During the “Duanwu” festival (5 May) the portrait of Zhong Kui is hung on doors to keep demons out. This painting was made by Xi Ding 西丁, famous artist of the Xian department of the Shaanxi provincial fine arts association. <Translation by Mr. Wang and P.M. Patings>

|

|

NOTEBOOK - RELATED MATTERS

- Japan Times Article, May 20, 2010. Boys' Day Festival (Tango no Sekku 端午の節句), held on May 5 each year, but now a festival for all children of both sexes. Says Yushichi Uehara, president and director of Inden-ya Company in Yamanashi Prefecture, which makes deer-skin craftwork adorned with intricate designs in shiny lacquer: "The iris has a very long history of use as a medicinal plant, and was used to ward off both evil and epidemics. It is also a symbol of masculine strength, which is one reason iris patterns often were used on armor and helmets." That association with health and strength is also why people still take a shobunoyu (iris bath) on May 5, adding bundles of iris leaves to their bath water. That day is now a national holiday called Kodomo no Hi 子供の日 (Children's Day), established in 1948. But it was originally Tangu no Sekku (Boy's Festival), and the iris bath was one way of praying for the safe growth of male children. Samurai also favored the iris pattern because there's some powerful word play involved. Shobu is the word for "iris," but if you write it with different characters it means "militarism." Substitute yet another set of characters and it means "battle." This kind of word play, called goro awase 語呂合わせ, was highly prized in many periods of Japanese history. <Source: Article in Japan Times May 20, 2010

-

The Art Institute of Chicago. “The Japanese often adopted characters of Chinese legend as cult figures, creating a demand that kept artists busily employed. Among the most popular characters was Shōki the Demon Queller, whose ghost came to Tang-dynasty emperor Xuanzong (reigned 712–756) in a dream and saved the ruler by vanquishing a demon that was making him ill. In the 17th century, the Japanese began using amulets depicting Shōki at the annual Boys’ Festival to ward off disease and instill a manly competitiveness in the participants. Okumura Masanobu’s 奥村政信 (1686-1764) print of a fierce, muscular Shōki honing his sword on a rough boulder (see photo at right) was likely produced for sale during the festival. The figure’s wild, untamed beard, hairy arms, and tiger-skin leggings underscore both his ferocity and his foreignness. <See photo at top of this page for another painting by Okumura Masanobu.> The Art Institute of Chicago. “The Japanese often adopted characters of Chinese legend as cult figures, creating a demand that kept artists busily employed. Among the most popular characters was Shōki the Demon Queller, whose ghost came to Tang-dynasty emperor Xuanzong (reigned 712–756) in a dream and saved the ruler by vanquishing a demon that was making him ill. In the 17th century, the Japanese began using amulets depicting Shōki at the annual Boys’ Festival to ward off disease and instill a manly competitiveness in the participants. Okumura Masanobu’s 奥村政信 (1686-1764) print of a fierce, muscular Shōki honing his sword on a rough boulder (see photo at right) was likely produced for sale during the festival. The figure’s wild, untamed beard, hairy arms, and tiger-skin leggings underscore both his ferocity and his foreignness. <See photo at top of this page for another painting by Okumura Masanobu.>

SOURCES, LEARN MORE

|

|