|

|

|

|

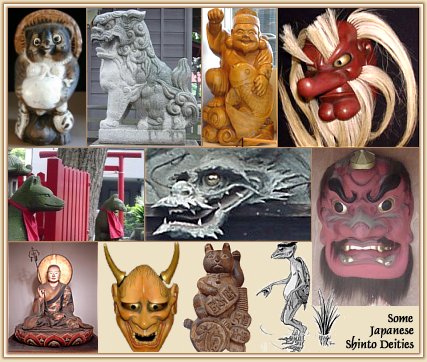

Shintō Deities (Kami), Supernatural Animals, Shintō Deities (Kami), Supernatural Animals,

Creatures, and Shape Shifters

Many Shintō deities in Japan incorporate Buddhist attributes.

Many Buddhist deities in Japan incorporate Shintō attributes.

The two faiths are inexorably intertwined despite earlier efforts to divide them.

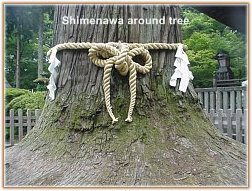

The Shintō pantheon of kami 神 (spirits) includes countless deities and innumerable supernatural creatures. The term KAMI can refer to gods, goddesses, ancestors, and all variety of spirits that inhabit the water, rocks, trees, grass, and other natural objects. These objects are not symbols of the spirits. Rather, they are the abodes in which the spirits reside. The abode of the kami is considered sacred and is usually encircled with a shimenawa (rope festooned with sacred white paper). The Japanese believe this world is inhabited by these myriad kami -- spirits that can do either good or evil. These spirits are constantly increasing in number, as expressed in the Japanese phrase Yaoyorozu no Kami 八百万神 -- literally "the eight million kami."

Kami are not necessarily benevolent. There are numerous Shintō spirits and demons that must be appeased to avoid calamity, but there is no absolute dichotomy between good and evil. All phenomena manifest "rough" and "gentle" characteristics. The noted Japanese scholar Motoori Norinaga 本居宣長(1730-1801) defined kami as anything that was "superlatively awe-inspiring," either noble or base, good or evil, rough or gentle, strong or weak, lofty or submerged. There is no definitive standard of good and evil, there is no moral code. Things are as they are. Even the evil bloodsucking Kappa has some redeeming qualities -- i.e., when benevolent, the Kappa is a skilled teacher in the art of bone setting and other medical practices.

Unlike Buddhism, whose deities are generally genderless or male, the Shintō tradition has long revered the female element. The emperor of Japan, even today, claims direct decent from the Shintō Sun Goddess Amaterasu. In modern Japan, both Shintō and Buddhist practice among the common folk has taken on the air of “this-worldly benefits” (concrete rewards now; Jp. = 現世利益, Genze Riyaku). To many Japanese, Shintō and Buddhist faith is primarily involved with petitions and prayers for business profits, the safety of the household, success on school entrance exams, painless child birth, and other concrete rewards now, in this life. Shintō deities are called KAMI 神, SHIN 神, JIN 神, SAMA 様, TENJIN 天神, GONGEN 権現, and MYŌJIN 明神 to distinguish them from their Buddhist counterparts. The latter are known as BUTSU 佛 and 仏 and NYORAI 如来 (all mean Buddha or Tathagata), BOSATSU 菩薩 (meaning Bodhisattva), TEN 天 (meaning Deva), MYŌ-Ō 明王 (meaning Luminescent Kings). See Terminology Page for more terms.

|

Shintō Kami (Deities)

|

|

What’s On This Page

Other Site Pages

|

Other Site Pages

|

|

Amaterasu Ōmikami 天照大神, the Sun Goddess Amaterasu Ōmikami 天照大神, the Sun Goddess

Aka Taiyōsama Amaterasu 太陽神アマテラス. Sun Goddess, Queen of Kami, She Who Illuminates the Heavens, the Supreme Shintō Deity. Also spelled Ōmikami, Omikami, Oumikami, O-mikami, O-mi-kami. Amaterasu is the child of Izanagi 伊邪那岐命 and Izanami 伊邪那美命 (creator gods of Japanese mythology). Japan’s imperial family claims direct decent from her line. The nation’s flag symbolizes the sun, and the name of the country (Nihon 日本) translates as “Land of the Rising Sun.” Shrines associated with the imperial family are called Jingū -- the most prestigious is called Ise Jingū (Mie Prefecture) and it is dedicated to Amaterasu. Ise Jingū is reportedly pulled down every 20 years and rebuilt in its original form. Japan’s numeous Shintō kami appear in Japan’s oldest extant document, the Kojiki 古事記 (Records of Ancient Matters; 712 AD), and also in the Nihongi 日本紀 (Chronicles of Japan; 797 AD). In Esoteric Buddhism, Amaterasu is considered the counterpart of Dainichi Buddha.

Following text courtesy Encyclopedia Mythica. “She was so bright and radiant that her parents sent her up the Celestial Ladder to heaven, where she has ruled ever since. When her brother, the storm god Susano-o no Mikoto 須佐之男命, ravaged the earth, she retreated to a cave because he was so noisy. She later closed the cave with a large boulder. Her disappearance deprived the world of light and life, which resulted in demons ruling the earth. The other gods used everything in their power to lure her out, but to no avail. Finally Uzume (aka Ame no Uzume 天宇受売命 or 天鈿女命) succeeded in bringing her out by dancing in front of the cave. The laughter of the gods as they watched Uzume’s comical and obscene dances aroused Amaterasu's curiosity. When she emerged from her cave a streak of light escaped (dawn). The goddess then saw her own brilliant reflection in a mirror which Uzume had hung in a nearby tree with beautiful jewels. When she drew closer for a better look, the gods grabbed her and pulled her out of the cave. She returned to the sky, and brought light back into the world. Later, she created and cultivated Japan’s rice fields. She also invented the art of weaving with the loom and taught the people how to cultivate wheat and silkworms. Many Shintō shrines contain a sacred mirror, said to be the mirror in which Amaterasu saw her reflection. Celebrations in her honor take place on July 17 each year. She is also honored on December 21, the winter solstice, to indicate her role in bringing light back to the world.”

Amaterasu and the Imperial Family. Amaterasu and the Imperial Family.

Emperor Akihito 明仁 (the current emperor) is said to be the 125th direct descendant of Emperor Jinmu 神武, Japan's legendary first emperor and a mythical descendent of Amaterasu. Says Kondo Takahiro: “Though not often referred to today, the Japanese calendar starts from 660 BC, the year of his legendary accession. The reigning emperors were considered to be the direct descendant of the Sun Goddess Amaterasu and revered as living gods at one time or another. When the Pacific War was imminent in 1940, the fascist government was boasting it was the year of 2600 to exalt the national prestige, and it even made a song cerebrating the 2600th year.”

|

Wartime Flag

|

|

Sun imagery is still very prominent in modern Japan. Japan’s national flag, the Hinomaru 日の丸 (literally sun circle; also known as Nisshōki 日章旗 or sun flag), symbolizes the sun, and was officially adopted by the Japanese Diet in August 1999, when the National Flag and Anthem Law was enacted. The exact origin of the hinomaru is unclear, but many point to the 12th century, when it appeared during a military campaign. Historically the hinomaru is a symbol of the reign of the “divine“ emperor. The country’s name, Nippon or Nihon, is typically translated as “Land of the Rising Sun” or “Source of the Sun.” The country’s national anthem, the kimigayo 君が代, also officially adopted in 1999, is a song of praise to the emperor. Its lyrics basically mean “May the emperor reign forever.” The imperial family's crest, the chrysanthemum, is used on the cover of Japanese passports.

|

Kimigayo Lyrics

Kimi ga yo wa

Chiyo ni yachiyo ni

Sazare ishi no

Iwao to nari te

Koke no musu made

|

English Translation

May the Emperor’s reign continue for

a 1000, nay, 8000 generations and for

the eternity it takes for small pebbles

to grow into a great rock and become

covered with moss.

|

Ancestral Spirits. See Deceased People below for more. Shintō asserts that all people are endowed with a soul or spirit (tama 霊, reikon 霊魂), and upon death, these souls may or may not find peace. Those who die happily among their family become revered ancestors. Ancestral spirits thereafter protect the family, and every summer they are welcomed back to the family home during Japan’s Obon お盆 festival (click photo for more Obon images). Those who die unhappily, or violently, or without a family to care for their departed spirit, or without the correct funeral and post-funeral rites, become ghosts who wander about causing trouble; they are typically called yūrei 幽霊 (tormented ghosts), and they must be appeased. This concept is akin to “hungry ghosts” in Buddhist philosophy -- the second lowest state in the Six Realms of Existence. Curiously, in Japan, funerals and graveyards are handled entirely by the Buddhist temples, not by the shrines. Ancestral Spirits. See Deceased People below for more. Shintō asserts that all people are endowed with a soul or spirit (tama 霊, reikon 霊魂), and upon death, these souls may or may not find peace. Those who die happily among their family become revered ancestors. Ancestral spirits thereafter protect the family, and every summer they are welcomed back to the family home during Japan’s Obon お盆 festival (click photo for more Obon images). Those who die unhappily, or violently, or without a family to care for their departed spirit, or without the correct funeral and post-funeral rites, become ghosts who wander about causing trouble; they are typically called yūrei 幽霊 (tormented ghosts), and they must be appeased. This concept is akin to “hungry ghosts” in Buddhist philosophy -- the second lowest state in the Six Realms of Existence. Curiously, in Japan, funerals and graveyards are handled entirely by the Buddhist temples, not by the shrines.

Animal Spirits. Many shrines are guarded by a pair of magical lion-dogs known as the Koma-inu 狛犬 or Shishi 獅子. The pair stand watch outside the Shintō compound to ward off evil spirits. Inari shrines, however, are guarded by two foxes. There are numerous magical creatures in the Shintō pantheon. For example, the Fox, the Tanuki, and the powerful birdman Tengu are well-known Shintō tricksters. Collectively they are called Henge, or shape-shifters, for they can transform into human or inanimate shapes to trick humans. Over the centuries, they have taken on both Shintō and Buddhist attributes. There are hundreds of legends and stories about human encounters with these magical creatures, who can do both good or evil. The stories are so varied and voluminous that Lafcadio Hearn referred to such legends as “Ghostly Zoology.” Other well-known animal kami are the Kappa (evil blood-sucking river imp) and Dragon (type of serpent). For more details on Shintō animal protectors, click here. Animal Spirits. Many shrines are guarded by a pair of magical lion-dogs known as the Koma-inu 狛犬 or Shishi 獅子. The pair stand watch outside the Shintō compound to ward off evil spirits. Inari shrines, however, are guarded by two foxes. There are numerous magical creatures in the Shintō pantheon. For example, the Fox, the Tanuki, and the powerful birdman Tengu are well-known Shintō tricksters. Collectively they are called Henge, or shape-shifters, for they can transform into human or inanimate shapes to trick humans. Over the centuries, they have taken on both Shintō and Buddhist attributes. There are hundreds of legends and stories about human encounters with these magical creatures, who can do both good or evil. The stories are so varied and voluminous that Lafcadio Hearn referred to such legends as “Ghostly Zoology.” Other well-known animal kami are the Kappa (evil blood-sucking river imp) and Dragon (type of serpent). For more details on Shintō animal protectors, click here.

Fox statues at Inari Shrine inside Tsurugaoka Hachimangū in Kamakura

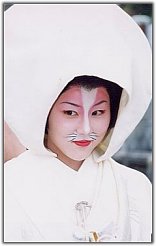

Fox Lady at one of Japan’s many Kitsune (Fox) Festivals

Deceased People or Ujigami (Clan Deities). Deceased individuals are sometimes deified and thereafter worshipped as Tenjin 天神 (lit. “heavenly spirits”). Shrines devoted to Sugawara Michizane Deceased People or Ujigami (Clan Deities). Deceased individuals are sometimes deified and thereafter worshipped as Tenjin 天神 (lit. “heavenly spirits”). Shrines devoted to Sugawara Michizane

菅原道真 (845-903 AD) and to Emperor Meiji 明治天応 are the two most prominent examples. Michizane (courtier in the Heian period) was deified after death, for his demise was followed shortly by a plague in Kyoto, said to be his revenge for being exiled. He is commemorated in the Gion Matsuri 祇園祭 (religious festival). Michizane is worshipped as the god of calligraphy and learning, and every year on the 2nd of January, students go to his shrines to ask for help in the school entrance exams or to offer their first calligraphy of the year.

Sometimes two human guardians dressed in ancient courtly robes sit or stand at opposite ends of the entrance to the main Shintō offertory hall. They are known as Udaijin 右大臣 (Minister of the Right) and Sadaijin 左大臣 (Minister of the Left). Michizane himself was once the Minister of the Right (Udaijin) for Emperor Kammu 桓武天皇 (737–806 AD), one of the highest ranking positions in Japan’s government.

There are also the Ujigami 氏神 (clan or village deities). These kami 神 are responsible for a particular community or locality, and in many cases, they represent the ancestors who founded the village (e.g., Fujiwara Shrine, Kasuga Shrine, Tachibana Shrine, Umemiya Shrine). The protective deity of one’s birthplace is called ubusunagami 産土神, and all the people living in one locality worshipping the local deity are called ujiko 氏子. In the Buddhist realm, there is a related term called danka 檀家 (households affiliated with a temple). These are families who select a temple based on their own individual convictions, and thereafter they rely on the temple for funeral and memorial services in exchange for monetary donations to the temple.

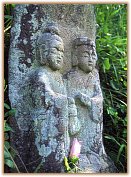

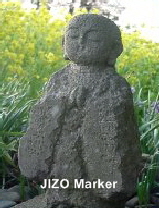

Dōsojin (Dosojin) 道祖神. Visit the Dōsojin Page for more details. Deities of Roads and Borders. Also called Sai no Kami or Dorokujin in some areas. These deities reside in stone markers found at village boundaries, in mountain passes, and along country byways. In urban areas today, dōsojin stone markers are often placed at street corners and near bridges to protect pedestrians. As the deity of the village border, the dōsojin wards off evil spirits and catastrophes, and protects the village from evil outside influences. As deity of the road, the dōsojin protects travelers, pilgrims, and those in "transitional" stages. These stone markers may bear only inscriptions, but often they depict human forms, in particular the images of a man and woman -- the latter manifestation is revered as the kami of marriage and fertility. In some localities, the dōsojin is worshipped as the kami of easy childbirth. Dōsojin (Dosojin) 道祖神. Visit the Dōsojin Page for more details. Deities of Roads and Borders. Also called Sai no Kami or Dorokujin in some areas. These deities reside in stone markers found at village boundaries, in mountain passes, and along country byways. In urban areas today, dōsojin stone markers are often placed at street corners and near bridges to protect pedestrians. As the deity of the village border, the dōsojin wards off evil spirits and catastrophes, and protects the village from evil outside influences. As deity of the road, the dōsojin protects travelers, pilgrims, and those in "transitional" stages. These stone markers may bear only inscriptions, but often they depict human forms, in particular the images of a man and woman -- the latter manifestation is revered as the kami of marriage and fertility. In some localities, the dōsojin is worshipped as the kami of easy childbirth.

Japan's popular Fire Festivals, held around January 15 each year, are known as Dōsojin festivals. Shrine decorations, talismans, and other shrine ornaments used during the local New-Year holiday are gathered together and burned in bonfires. They are typically pilled onto bamboo, tree branches, and straw, and set on fire to wish for good health and a rich harvest in the coming year. The practice of burning shrine decorations has many names, including Sai-no-Kami, Sagicho, and Dondo Yaki. According to some, the crackling sound of the burning bamboo tells the listener whether the year will be lucky or not. Children throw their calligraphy into the bonfires -- and if it flies high into the sky, it means they will become good at calligraphy. (above two photos courtesy kazekobo.cool.ne.jp) Japan's popular Fire Festivals, held around January 15 each year, are known as Dōsojin festivals. Shrine decorations, talismans, and other shrine ornaments used during the local New-Year holiday are gathered together and burned in bonfires. They are typically pilled onto bamboo, tree branches, and straw, and set on fire to wish for good health and a rich harvest in the coming year. The practice of burning shrine decorations has many names, including Sai-no-Kami, Sagicho, and Dondo Yaki. According to some, the crackling sound of the burning bamboo tells the listener whether the year will be lucky or not. Children throw their calligraphy into the bonfires -- and if it flies high into the sky, it means they will become good at calligraphy. (above two photos courtesy kazekobo.cool.ne.jp)

The origin of dōsojin stone markers is shrouded in the mists of uncertainty, and no exact date can be given. But precedents are ample in the Buddhist world. Here again we meet one of Japan's most popular and beloved deities, Jizo Bosatsu. In the early centuries following the birth of Buddhism in India (around 500 BC), Jizo became known as the guardian of travelers and pilgrims, and statues of his image could be found along pilgrimage routes and mountain passes in India and Southeast Asia. Buddhism was introduced to Japan much later, in the 6th century AD. The tradition of stone markers was also eagerly adopted by Japan, where even today one can find groupings of six Jizo statues standing guard on the high roads or at busy intersections. Among the many trails zigzagging the foothills of Kamakura, and elsewhere throughout Japan, one can also find solitary figures of Jizo guarding the way. . The origin of dōsojin stone markers is shrouded in the mists of uncertainty, and no exact date can be given. But precedents are ample in the Buddhist world. Here again we meet one of Japan's most popular and beloved deities, Jizo Bosatsu. In the early centuries following the birth of Buddhism in India (around 500 BC), Jizo became known as the guardian of travelers and pilgrims, and statues of his image could be found along pilgrimage routes and mountain passes in India and Southeast Asia. Buddhism was introduced to Japan much later, in the 6th century AD. The tradition of stone markers was also eagerly adopted by Japan, where even today one can find groupings of six Jizo statues standing guard on the high roads or at busy intersections. Among the many trails zigzagging the foothills of Kamakura, and elsewhere throughout Japan, one can also find solitary figures of Jizo guarding the way. .

Kami 神 (also pronounced SHIN) Kami 神 (also pronounced SHIN)

The term KAMI can refer to gods, goddesses, great ancestors, and all variety of spirits that inhabit the water, rocks, trees, grass, and other natural objects. These objects are not symbols of the spirits -- rather they are the abodes in which the spirits reside. The abode of the kami is considered sacred, and is usually encircled with a shimenawa (rope festooned with sacred white paper). For photos and further details, please visit the Shrine Guide.

The Japanese believe this world is inhabited by myriad kami -- nature spirits that can do either good or evil. These spirits are constantly increasing in number, as expressed in the Japanese phrase yaoyorozu no kami -- literally “the eight million kami,” which can also be translated as “innumerable kami.”

Kami are not necessarily benevolent. There are numerous Shintō demons (Oni) and spirits (Kappa) that must be appeased to avoid calamity, but there is no absolute dichotomy between good and evil -- all phenomena manifest "rough" and "gentle" characteristics. The noted Japanese scholar Motoori Norinaga defined kami as anything that was "superlatively awe-inspiring," either noble or base, good or evil, rough or gentle, strong or weak, lofty or submerged -- there is no definitive standard of good and evil, there is no moral code. Things are as they are. Even the evil bloodsucking Kappa has some redeeming qualities -- i.e., when benevolent, the Kappa is a skilled teacher in the art of bone setting and other medical practices.

Says Alan Watts in The Watercourse Way: ”The term ‘kami’ presents problems for the translator, for the usually chosen meanings -- spirit, god, divine, supernatural -- are unsatisfactory. I take it to mean that innate intelligence (or li 理) of each particular organism. Li is translated as ‘organic pattern,’ an ideogram which referred originally to the grain in jade and wood, although it is more generally understood as the ‘reason’ or ‘principle’ of things.” <Editor’s Note: Of course Watts is talking about the Chinese term Shen, which in Japan is pronounced either Kami or Shin.

Small shrine named Towada-ko, photo by Matt Berlow

- Kamikaze

神風 | かみかぜ | Kamikaze

Literally “divine wind” or “wind from the gods” that blew the invading Mongolian fleet off course, saving Japan from invasion in the 13th century. Also the name of the suicide bombers of Japan’s imperial armed forces during World War II.

Nature Spirits, Earth Elements, and Powerful Forces Nature Spirits, Earth Elements, and Powerful Forces

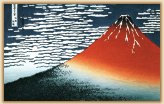

Sun, wind, rivers, lakes, trees, rocks, mountains, agriculture, war. The most important kami is the Sun Goddess Amaterasu. To the Japanese, Mt. Fuji is the nation’s most sacred mountain, wherein lives a powerful kami. Tour groups and individuals climb it regularly as an act of worship. Agriculture itself is deemed a powerful force. Inari, the kami of agriculture, has shrines all over Japan. Inari’s messenger is the magical and mischievous fox. Hachiman, the god of war, is also highly revered at Hachimangu shrines throughout Japan. One of the most predominant is Tsurugaoka Hachimangu, located in Kamakura. It was founded by the military lord Minamoto Yoritomo, who established the Kamakura shogunate, and a sub-shrine dedicated to the Minamoto clan is within its compound.

Suijin 水神 or Water Kami Suijin 水神 or Water Kami

See the Suijin page for more details. These creatures of Shinto mythology are found near irrigation waterways, in lakes, ponds, springs and wells. They can be depicted as a serpent, an eel, a fish, or a kappa. According to the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics (Kokugakuin University), women have played an important role in the history of Suijin worship in Japan. Another widely known Suijin is the dragon (called Ryujin in Japanese); the dragon is also closely associated with Buddhism, and is considered the most powerful of the serpents 竜神 Ryuujin. .

- Yurei (Ghosts). For reasons unknown to me, Shinto does not deal with death and funerals. In modern Japan, funerals and graveyards are handled by Buddhist temples. Nonetheless, Shinto asserts that all people are endowed with a spirit or a soul, called reikon, and when we die, we all become kami. Those who die peacefully and happily among their family members become revered ancestors. Ancestral spirits protect the family, it is believed, and every summer they are welcomed back to the family home during Japan’s Obon festival. Those who die unhappily, or violently, or without a family to care for their departed spirit, or without the correct funeral and post-funeral rites, become hungry ghosts (one of the lowest states of existence in Buddhism; click here for details). These hungry ghosts wander about causing trouble; they are typically called yurei (tormented ghosts). Most younger Japanese don’t remember that the Obon holidays are also a time when the gates of hell are uncovered, and the hungry ghosts allowed to return to their ancestral haunts.

Shinto Kami (Deities)

For a more comprehensive deity list, click here.

- Funadama

http://www2.kokugakuin.ac.jp/ijcc/wp/bts/bts_f.html#fukko_shinto

A spirit worshiped by fishermen and seafarers as a protector of ships. A hole is made in the mast of the ship and certain items are inserted to symbolize the spirit; these items may include a woman's hair, dolls, two dice, twelve pieces of money, and the five grains. Widely believed to be a goddess, and to grant abundant catches if worshiped when catches are poor.

- Umi no kami

God of the sea. The deity ruling the ocean, in fact considered to be three deities called Watatsumi no Kami. In popular belief, the dragon-god (ryūjin) is thought of as god of the sea and is worshiped at a festival around June. Among groups with ocean-related occupations, many taboos are placed on words (i.e., imikotoba or word taboos) and actions while at sea in an effort to avoid angering the god of the sea.

Below text from Kokugakuin University

http://eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp/modules/xwords/entry.php?entryID=232

"Kami of the sea," a tutelary of the ocean and ocean travel. Believed to live in the sea or the "other world" at the bottom of the sea, the umi no kami is a nature deity believed to have dominion over ocean winds and waves, the tides, and rains. It was anciently believed that if the sea kami were angered, it would bring high winds and disturb the activity of fishing, but if properly placated, it would assure fishermen safe passage for their boats, and bountiful catches of fish. The sea was called wata or wata no hara (the ocean plain), with the result that the sea kami was commonly referred to as Watatsumi. According to the myths of the Nihongi and Kojiki, the sea kami Watatsumi appears as the offspring of Izanagi and Izanami. In the myth of the "sea blessing" (umisachi) and "mountain blessing" (yamasachi), it was the deity Watatsumi living in his undersea palace who assisted Hohodemi (Yamasachibiko) by retrieving the fishhook belonging to Hohodemi's elder brother Umisachibiko. The ocean tutelaries worshipped at the shrines Sumiyoshi Jinja and Munakata Taisha are believed to be related to this same Watatsumi of myth. On the other hand, the sea kami which served as the common people's objects of supplication for safe ocean passage and abundant catches on the sea had little relation to the kami of myth. For example, the popular kami called ryūjin ("dragon deity") was the product of a combination of Chinese dragon motifs with the snake worshiped in a local water-deity cult. The identification of ryūjin with sea kami is also reflected in the taboo (imi) against dropping metal objects into the sea, based on the belief that dragons and snakes loathe such objects. The cult of the dragon deity as a sea kami is believed to have been particularly spread by practitioners of the mountain religion called Shugendō?. In the form of a snake, the kami of the Konpira Shrine was worshiped by sea-farers who revered the shrine's deity as a tutelary who would protect them from the perils of the sea. The kami Ebisu is likewise worshiped as a sea kami by fishermen who believe the deity is responsible for "luck" in fishing. In Kojiki and Nihongi, sea kami are portrayed as living in another world called Tokoyo or Watatsumi, while in Okinawa such kami are thought to live in palaces in paradisical lands called Nirai and Kanai, located far beyond or under the sea. Such lands are viewed as being accessible to human beings, and legends can be found widely throughout Japan relating stories of individuals led to undersea dragon palace in return for aiding sea turtles or fish, who were considered servants of the sea kami. <end quote>

- Watatsumi no Kami (Kojiki)

Watatsumi no Mikoto (Nihongi)

http://eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp/modules/xwords/entry.php?entryID=172

A tutelary of the sea. According to Kojiki, the sea deity Ōwatatsumi no kami was produced by Izanagi and Izanami as part of the process of giving birth to the kami (kamiumi). Both Kojiki and Nihongi record that when Izanagi returned from the underworld land of Yomi and performed ablution (see misogi, harai), three Watatsumi deities were produced, representing the "upper" (Uwawatatsumi) "middle" (Nakawatatsumi) and "bottom" (Sokowatatsumi) parts of the water where he bathed. The name Watatsumi derives from the words wata-tsu-mochi, literally meaning "holder of the sea," indicating a kami with domain over the ocean. The Kojiki account also records that Hoori no mikoto (Yamasachi) traveled to the undersea palace of the ocean kami Watatsumi and married Watatsumi's daughter Toyotamabime. See also umi no kami.

Legends in Japanese Art

Generic name of the numberless legions of Shinto deities, for extensive lists of which the Kojiki and Nihongi should be consulted. The soul of every man becomes Kami after death.

KAMI SAMA shoots once a year an arrow into the thatch of a house to

give notice that he wishes to eat a girl, failing which he will destroy the

crops and cattle. In Anderson's version, the woman fails at the first attempt, and Kamatari resorts to the use of musicians in a boat to draw from Riujin's palace its faithful attendants. The diver then attacks the dragon whilst his retainers are away. In most cases, however, the boat filled with musicians is not represented. See also Aston's Shinto and Hearn's works.

Several of the Kami are protective deities of the soil (from 155 LEGEND IN JAPANESE ART)

- UGA NO MITAMA NO MIKOTO is the spirit of food.

- SUKUNA IIIKONA NO KAMI, the scarecrow god.

- SUIJIN SAMA is the god of the wells.

- KOJIN, of the kitchen fire, assisted by the deities of the cauldron, KITSU HIKO (Kudo no Kami), and of the saucepan, O Krrsu HIME (Kobe no Kami), and the god of the rice pots, O KAMA SAMA; while the ponds chief deity is IKE NO NUSHI NO KAMI, the god of trees, KUKUNOCHI NO KAMI. The goddess of grasses is KAYANU HIME NO KAMI; another god of trees is AMANOKO. The moon has her deity, JOKWA; the divinity of fever is KARU, depicted astride a fish with a yellow toad on her head.

- Some of the Kami are black; they have ghostly faces with pointed mouths. They come from the starving circle of Hell, and are the gods of hunger, of penuriousness, of poverty (Bimbogami), of hindrances and obstacles, of small pox (Hoso no Kami), of colds (Kaze no Kami), of pestilence (Yakubiogami).

- Lightning was forged by ISHI NO KORE, TAJIKARA is the god of the dragons, and SARASVATI is the goddess of language, borrowed from the Indian pantheon. Each god has three spirits: the rough Aramitama, the gentle Nigi mitama, and the bestowing Saki mitama. See Hearn's works and Satow's Revival of Pure Shinto.

- Kami XXXXX ???? ovoshi is a sort of ecstatic trance, perhaps of an auto-hypnotic character, which is considered to be a union with the divinity.

LEARN MORE

|

|