|

|

|

|

SHINTŌ FESTIVALS, RITES, & CEREMONIES SHINTŌ FESTIVALS, RITES, & CEREMONIES

The main Shintō rites and festivals are for celebrating the New Year, child birth, coming of age, planting and havest, weddings, and groundbreaking ceremonies for new buildings. Death, funerals, and graveyards involve Buddhist rituals, not Shintō. Many national holidays in modern Japan are Shintō in origin. Shintō shrines hold regular festivals (matsuri 祭り) to commemorate important dates related to the shrine and its deity(s) and to pray for a wide range of blessings such as abundant rice harvests, fertility, health, and business success. The essential meaning of the term matsuri is “welcoming the descending gods” or “inviting down the gods,” for it is believed that Shintō’s heavenly deities periodically descend to earth to visit shrines, villages, and families, and to make their wills known among the people. The timing of these visitations equates to the timing of Japan’s Shintō festivals. There are countless festivals in Japan, ranging from public to private, local to national, and official to unofficial. These celebrations are an integral part of Japan’s Shintō traditions, and often include parades, music and dancing, theatrical performances, food and games, and the carrying of mikoshi 神輿 (portable shrine or palanquin used to transport Shintō deities) throughout the streets. Many localities, for example, hold their own “Fertility” festival, wherein local residents carry around large portable shrines that depict the male sexual organ. Some of Japan’s main Shintō festivals are discussed below.

WHAT’S ON THIS PAGE

Festival Timing and Main Features

Today many temples and shrines continue to use the lunar calendar for important festivals and events. In the lunar calendar, the new moon (1st of the month), the half-moon of the first quarter (7th or 8th), the full moon (15th), and the half-moon of the last-quarter (22nd or 23rd), are considered sacred days and known as Hare-no-hi 晴れの日~ハレのひ. All other days of the months are known as Ke-no-hi 褻の日~けのひ. Until modern times, Japan’s most important festivals were almost always held on Hare-no-hi days. People in former times believed the day began and ended from sunset to sunset, so festivals were normally held from the eve of the festival (yoi matsuri 宵祭り) into the daylight hours of the main festival day (hon matsuri 本祭り) -- with festivities ending at sunset on the main festival day. Thus, Hare-no-hi festivals typically lasted only 24 hours, from sunset to sunset. Additionally, Japanese festivals are commonly divided into three general groups -- those held in spring and autumn (related to the planting and the harvest of the rice crop), those held in summer (related to avoiding drought, natural disasters, disease, and other calamities that might harm the rice crop), and those held in winter (related to the health and safety of the nation, its people, and the imperial household).

|

|

Hare-no-hi 晴れの日

Sacred Days in Lunar Calendar

|

|

|

New

Moon

|

Half Moon

1st Qrt.

|

Full

Moon

|

Half Moon

3rd Qrt.

|

|

|

1st

|

7th or 8th

|

15th

|

22 or 23

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today, however, the situation is more complicated. In Japan, the lunar calendar was abandoned in 1872 in favor of the solar (Gregorian) calendar. See Zodiac page for details. Even so, the lunar calendar is still used by some locations, while the solar calendar is used by others. The three methods used today for dating important festivals and events are:

- One month is added to the lunar calendar. For example, if a festival occurred on May 1st in the lunar calendar, it will occur on June 1st using the solar calendar.

- The lunar calendar is still used to calculate the equivalent solar date. If the festival occurred on May 1st in the lunar calendar, it will be held on/about June 1 in the solar calendar.

- No change. If the festival occurred on May 1 in the lunar calendar, it will occur on May 1 in the solar calendar.

Festivals (Matsuri 祭り) are typically divided into three main parts

- Kami Mukae 神迎え or Kami Mukae-sai 神迎祭, literally "welcoming the kami." Shrines and temples hold a special welcoming ceremony to invite the deities to earth.

- Shinkō 神幸 or Shinkōsai 神幸祭 or Shinkō-shiki 神幸式. Also read as Miyuki 御幸 or Gyōkō 行幸. The main festival event, literally the "procession of the kami" or "sacred procession." Typically this involves the local community parading about the streets or shrine precincts carrying a palanquin (mikoshi) in which the kami are enshrined. This gives the kami a chance to tour their territory.

- Kami Okuri 神送り, literally "sending the kami back" to their heavenly abodes. The kami are not abandoned at the end of the festival, but respectfully sent back to their abodes. To do otherwise would, according to Japanese sensibilities, invite disaster.

Daijōsai 大嘗祭

The Great Food Festival. An elaborate variation of the annual rice-tasting ceremony known as Niinamesai 新嘗祭. For more details, see JAANUS (outside link).

Dōsojin Matsuri 道祖神祭り Dōsojin Matsuri 道祖神祭り

Japan's popular Fire Festivals, held around January 15 each year, are known as Dōsojin festivals. Shrine decorations, talismans, and other shrine ornaments used during the local New-Year holiday are gathered together and burned in bonfires. They are typically pilled onto bamboo, tree branches, and straw, and set on fire to wish for good health and a rich harvest in the coming year. The practice of burning shrine decorations has many names, including Sai-no-Kami, Sagicho, and Dondo Yaki. According to some, the crackling sound of the burning bamboo tells the listener whether the year will be lucky or not. Children throw their calligraphy into the bonfires -- and if it flies high into the sky, it means they will become good at calligraphy. Dōsojin is also a Japanese folk deity, one who protects mountain passes, crossroads, and village boundaries (the deity is believed to block the passage of evil spirits and gods of disease). Dōsojin is also closely associated with fertility (both in crops and people) and is considered a god of stones. Dōsojin statues can be found everywhere in Japan. Visit the Dōsojin page to learn much more. PHOTO: The bearded fellow in the above photo is me.

Harai 祓い

Exorcising, cleansing, and purification rites. Similar to groundbreaking rituals (see Jichinsai). For example, new airplanes are purified before their maiden flight, and many car owners take their new vehicles to shrines to be blessed and purified.

Hatsumode 初詣 Hatsumode 初詣

First shrine visit of the New Year. Hatsumode literally means “to pay the first visit of the year to the shrine,” where one expresses gratitude for divine protection during the past year and gains the blessings of the local shrine for ongoing protection in the coming year. Typically, the Shintō priest gives a short talk, then welcomes all to share a small cup of sake 日本酒. Bonfires are typically lit as well. Even if people can’t make the formal event, most try to visit a shrine sometime in early January.

Jichinsai 地鎮祭

Groundbreaking rituals. Shintō ceremony of purifying a building site or ceremony to sanctify the ground. In Japan, purification ceremonies precede the commencement of all important events and functions. When a new building or home is to be constructed, a groundbreaking ceremony called Jichinsai is performed to pacify the earth kami and to purify the spot where construction will take place.

Kekkonshiki 結婚式 (Weddings) Kekkonshiki 結婚式 (Weddings)

Weddings. Most Japanese weddings include a vow before the kami. The wedding ceremony usually takes place at hotels or gorgeous ceremony halls -- specifically designed for weddings, and with makeshift shrine altars. A Shintō priest with whom the hotel or hall has a contract presides over the wedding rituals, reciting prayers and norito 祝詞 (ritualistic words spoken in an archaic style of Japanese). One unique Shintō wedding practice is called San-san-kudo 三々九度 (three-three-nine-times), or three-time exchange of nuptial cups. Three flat cups (dishes with small, medium and large sizes) are used, and sake is poured into each, and the groom first sips it three times. The bride then follows him. The moment the ritual is finished, the couple officially becomes wedded under Shintō tradition. (Text Courtesy Kondo Takahiro) Traditionally, at the wedding reception, a cask of sake is served. The photo above shows a traditional-style sake cask.

Miyamairi 宮参り

Christenings, Baptisms. One month after birth (31st day for boys, 32nd day for girls), parents and grandparents take the child to a shrine to express gratitude and ask shrine priests to pray for their baby’s good health and happiness. This is a Japanese version of infant baptism. Today, Miyamairi is generally performed between one month to 100 days after birth. Says Kondo Takahiro: “In famous and busy shrines, the ceremony is held every hour in turn. A group of a dozen or so babies and their families are usually brought into the Shintō hall, one group after another. There is no price list for the service, but it usually costs around 10,000 yen per baby. The group is led in by turn and they sit in front of (facing) the alter. A Shintō priest (kannushi 神主) wearing a unique Shintō costume and headgear appears between the group and the altar, and starts to recite a prayer or incantation (norito 祝詞), swinging the tamagushi 玉ぐし right and left (the tamagushi is a sprig of Cleyera orchnacca with attached white-paper strips used by Shintō priests at ceremonies). We don't understand what he is saying, except that somewhere in the middle of the prayer, the priest cites the name of the baby and his/her birthday. The prayer continues for about ten minutes. And then, parents carrying the baby go forward one by one and bow to the altar. In the end, sake, or rice wine, in a red wooden cup, is given to each of them.” (Text Courtesy Kondo Takahiro)

National Holidays, Other Important Annual Events

- New Year's Day, Shōgatsu 正月. January 1. National Holiday. Established in 1948, but prior to then it was an important ceremonial day of imperial worship known as Shihō-hai 四方拝. Today most Japanese businesses are closed from Dec. 29 through Jan. 3. At the beginning of the year, many Japanese visit a shrine to express gratitude for divine protection during the past year and to gain the blessings of the local kami for ongoing protection in the coming year. This first shrine visit of the new year is called Hatsumode 初詣. At Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine in Kamakura alone, some two million people visit the shrine over three days during the New Year holiday. Japanese also make pilgrimages devoted to the Seven Lucky Gods during the month of January.

- Coming of Age Day or Adults Day, Seijin-no-hi 成人の日. National Holiday. Held on the second Monday in January each year, when young people who have turned 20 go to a shrine for their "coming of age" ceremony. In Japan, by the way, you must be 20 years old to vote, to drink alcohol, and to drive a car.

- Bean-Throwing Ceremony, 節分. February 3 each year. A major event, but not a national holiday. People nationwide throw beans outside their home and inside their home chanting Oni wa Soto, Fuku wa Uchi 鬼は外福は内 (Get out Ogre! Come in Happiness!). See Setsubun in Japan; A Lunar New Years' Eve by Steve Renshaw and Saori Ihara.

- National Founding Day, Kenkoku Kinen no Hi 建国記念の日. February 11. National Holiday. Established in 1966.

- Girl's Festival or Doll Festival, Hina Matsuri 雛祭り or Momo no Sekku 桃の節句 (Peach Festival). March 3. A major event, but not a national holiday. Geared towards girls, the first sekku (seasonal festival) after the birth of a baby girl, it is a day when dolls are set out for display and meant to symbolize the family's wish that their daughter will be healthy, free from calamity, and able to obtain a happy life with a good husband. Today called the Peach festival, as March is the season when peach flowers are in bloom.

- Vernal Equinox Day, Shunbun no Hi 春分の日. Around March 20 or 21. National Holiday. Established in 1948, but in former times a very important day for the imperial family and court.

- Buddha's Birthday Festival, Hana Matsuri 花祭り, April 8th. Not a national holiday. Every year on April 8th in Japan, a ceremony called Kanbutsu-e 潅仏会 is held to commemorate the Historical Buddha's birthday. A small statue of the Buddha is typically sprinkled with hydrangea tea or with scented water called Goshiki Sui 五色水 (lit. Five-Colored Water). The ceremony recreates a legend, in which the newly born Buddha was sprinkled with perfume by the dragon god (ryū-ō 竜王). A small shrine, known as the Hanamidō 花御堂 is set up and decorated with flowers. A small image of the Buddha, in the form of a child as he appeared at birth (Tanjōbutsu 誕生仏), is placed on a wide, shallow metal bowl, known as the Kanbutsu-ban 潅仏盤. The statue of Buddha has the right hand held up, and the left hand pointing down, depicting the moment when Buddha took seven steps forward and pronounced the words "Tenjō tenga yuiga dokuson 天上天下唯我独尊" (I alone am honored in heaven and on earth). Visitors to the temple where the ceremony is performed use a small ladle to sprinkle scented water over the top of the statue. The kanbutsu-e ceremony was brought to Japan from China, and the first recorded celebration in Japan was at Gankōji 元興寺 in Nara in 606. It spread to become a regular part of Buddhist tradition in other temples, the court, and among ordinary citizens. A famous Kanbutsu-ban decorated with hunting scenes is preserved in Nara's Tōdaiji 東大寺. It dates from the Nara Period and shows outstanding metal craftsmanship. <Source JAANUS>

- Shōwa Day, Shōwa no Hi 昭和の日. April 29. Originally a national holiday celebrated on the Shōwa emperor's birthday (April 29), but after the emperor's death in 1989, it was renamed Greenery Day (Midori no Hi みどりの日). In 2007, Greenery Day was moved to May 4 and added as a new national holidy, with April 29 renamed as Shōwa Day and remaining a national holiday. Shōwa Day also marks the start of Japan's Golden Week schedule, when a number of national holidays fall in rapid succession.

- Constitution Memorial Day, Kenpō Kinenbi 憲法記念日. May 3. National Holiday. Established in 1948.

- Greenery Day, Midori no Hi みどりの日. May 4. National Holiday. See Shōwa Day above for more details. A day to celebrate nature and her blessings.

- Children's Day, Kodomo no Hi こどもの日. May 5. National Holiday. Established in 1948 to celebrate the nation's children. It was formally known as the Boys' Day Festival (Tango no Sekku 端午の節句), but it is now a festival for all children of both sexes. The end of Japan's Golden Week schedule.

- The Star Festival, Tanabata 七夕. July 7. Not a national holiday, but a nationwide day of celebration and festivals devoted to two lovers (two stars of the Milky Way) who are allowed to meet only once a year.

- Marine Day, Umi no Hi 海の日. Third Monday in July. National Holiday. Establish in 1995 to celebrate the blessings of the ocean.

- Festival of the Dead or Festival for Deceased Ancestors, Obon お盆. August 15 or so. Not a national holiday, but a widely celebrated Buddhist holiday nationwide that lasts three days. Its starting dates differ based on region. The Obon period is when the spirits of the ancestors return to their former habitats and are welcomed by their living descendants. In modern Japan, many people return to their hometowns to tend to the graves of their ancestors. At the end of the Obon period, the spirits are sent off again on floating lanterns that are set adrift in rivers.

- Respect for the Aged Day, Keirō no Hi 敬老の日. Third Monday in September. Established in 1966 to celebrate the nation's elderly.

- Autumnal Equinox Day, Shūbun no Hi 秋分の日. Around September 23. National Holiday. Established in 1948, but in former times a very important day for the imperial family and court.

- Health-Sports Day, Taiiku no Hi 体育の日. Second Monday in October. National Holiday. Established in 1966 and held on Oct. 10, but since changed to the second Monday in October.

- Culture Day, Bunka no Hi 文化の日. November 3. National Holiday. Establish in 1948, but before that celebrated as the birthday of the Meiji emperor.

- Seven, Five, Three Festival for Children, Shichi-go-san 七五三. November 15. Not a national holiday, but widely celebrated nationwide. Each year, children aged seven, five, and three don their finest traditional garb and visit their local shrines to be blessed. Special Shintō rites are performed to formally welcome girls (age 3) and boys (age 5) into the community. Girls (age 7) are welcomed into womanhood and allowed to wear the obi (decorative sash worn with kimono).

- Labor Thanksgiving Day, Kinrō Kansha no Hi 勤労感謝の日. November 23. National Holiday. Established in 1948, but before then it was celebrated as the Imperial Harvest Festival (Niinamesai 新嘗祭). A rice-tasting ceremony (one of Shintō’s main rituals) is performed each year when the emperor offers the newly harvested rice to the gods and then eats a little himself.

- Emperor's Birthday, Tennō Tanjōbi 天皇誕生日. December 23. National Holiday.

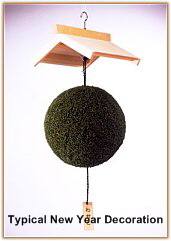

- New Year's Eve, Ōmisoka 大晦日. December 31. Not a national holiday. Preparations begin well before Dec. 31, when Japanese households, schools, and businesses clean their habitats from top to bottom. Kadomatsu 門松 (a decoration made of pine branches and bamboo) and shimekazari 注連飾り (rope of straw with strips of white paper) are placed in front of the house). Ōmisoka usually starts when families settle down to watch special New Year variety shows on television, commonly featuring popular entertainers and singers. Toshikoshi-soba 年越し蕎麦 (long, thin buckwheat noodles) are traditionally eaten.

Niinamesai 新嘗祭

Rice Tasting Ceremony. One of Shintō’s main rituals, performed each year when the emperor offers the newly harvested rice to the gods and then eats a little himself.

Seijin-no-hi 成人の日

Coming of Age or Adults Day. Held on the second Monday in January each year, when young people who have turned 20 go to a shrine for their “coming of age” ceremony. In Japan, by the way, you must be 20 years old to vote, to drink alcohol, and to drive a car.

Shichi-go-san 七五三

Seven five three ceremony. On November 15 each year, children aged seven, five, and three don their finest traditional garb and visit their local shrines to be blessed. Special Shintō rites are performed to formally welcome girls (age 3) and boys (age 5) into the community. Girls (age 7) are welcomed into womanhood and allowed to wear the obi (decorative sash worn with kimono).

LEARN MORE

|

|