|

|

|

|

DAIKOKU, DAIKOKUTEN, DAIKOKU-TEN

Daikokuten 大黒天 literally means “Great Black Deva”

God of Earth, Agriculture, Rice, Farmers, the Kitchen, & Wealth

Main Shintō Association = Ōkuninushi no Mikoto 大国主命.

Other Shintō Associations = Ōmononushi-no-mikoto 大物主尊

and also Ōnamuchi 大穴牟遅神 (Kojiki) or 大己貴神 (Nihongi).

Identities: Ōnamuchi = Ōmononushi = Ōkuninushi = Daikokuten

Ōkuninushi is the son of Susano-Ō-no-Mikoto

Origin India

Member of the Tenbu (Skt. = Deva)One of Japan’s Seven Lucky GodsAssociated Virtue = Fortune

|

SEVEN VIRTUES

Japan's Seven Lucky Gods are a popular grouping of deities

that appeared from the 15th century onward. The members of

the grouping changed over time, but a standardized set

appeared by the 17th century. In the 17th century, Japanese

monk Tenkai (who died in 1643 and was posthumously named

Jigen Daishi) symbolized each of the seven with an essential

virtue for the Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu (1623-1650 AD).

The seven virtues are:

- Candour (Ebisu)

- Fortune (Daikokuten)

- Amiability (Benzaiten)

- Magnanimity (Hotei)

- Popularity (Fukurokuju)

- Longevity (Juroujin)

- Dignity (Bishamonten)

References: Flammarion Iconographic Guide - Buddhism

|

Click any image to enlarge

1. Daikoku, Date Unknown, Found on web, No data available

2. Daikoku, Hase Dera, Kamakura, 15th Century (circa 1412)

3. Daikoku, Private Garden, Kamakura, Early Showa Era

4. Daikoku, Zuisenji Temple, Kamakura, Muromachi Era

All New, Sept. 17, 2017

Historical Notes

Male. Originally a Hindu warrior deity named Mahākāla (an emanation of Śiva; transliterated Makakara 摩訶迦羅), but later adopted into the Buddhist pantheon and appearing by at least China’s Sui 隋 dynasty (581-618) in Buddhist texts. In esoteric schools, he is also considered the masculine form of Kālī (i.e. Durgā), the wife of Śiva, or else a form of the war god Daijizaiten (another Japanese name for Śiva).

Daikokuten 大黒天 or Daikoku 大黒 is widely known in Japan as the happy-looking god of wealth, farmers, food, and good fortune, although in earlier centuries he was considered a fierce warrior deity. The oldest extant image of Daikokuten in Japan is dated to the late Heian period (794-1185) and installed at Kanzeonji Temple 観世音寺 (Fukuoka prefecture). The statue depicts the deity with a fierce expression, reminding us of his Hindu origin as a war god, as does the late-Heian sculpture of Daikoku at Kongōrinji Temple 金剛輪寺 (Shiga prefecture), which shows him dressed in armor. <See photos below>

However, since the early 14th century, Japanese artwork of this deity starts showing him as a cheerful and pudgy deity wearing a peasant’s hat (called Daikoku-zukin 大黒頭巾) and standing on bales of rice (tawara 俵), carrying a large sack of treasure slung over his shoulder and holding a small magic mallet. There are other forms, including a female form, but in Japan, the god is invariably shown standing on two bales of rice holding his magic mallet and treasure sack. Images, paintings, and other artwork of Daikokuten can be found everywhere in modern Japan, showing him alone, paired with Ebisu (considered his son in many traditions), or grouped with the Seven Lucky Gods. He appears on posters, key chains, mobile-phone accessories, toys for children, and many other commercial goods.

Daikoku is also considered a deity of the kitchen and a provider of food, and images of him can still be found in the kitchens of monasteries and private homes. This tradition is thought to have come from India and China, where images of Mahākāla (Daikoku's Sanskrit name) were placed in monastery kitchens to provide for the nourishment of the monks. In Japan, the practice is thought to have been introduced on Mt. Hiei 比叡 in the 9th century by Saichō 最澄 (767-822), the founder of Japan's Tendai sect. Saichō is also credited with introducing a three-headed form of Daikoku known as Sanmen Daikoku. In addition, says the Buddhism (Flammarion Iconographic Guides) , “The main pillar of a house in the traditional Japanese style assumes the name of Daikoku-bashira 大黒柱 or ‘pillar of Daikoku,’ meaning ‘pillar of luck and wealth.’” <end Flammarion quote> , “The main pillar of a house in the traditional Japanese style assumes the name of Daikoku-bashira 大黒柱 or ‘pillar of Daikoku,’ meaning ‘pillar of luck and wealth.’” <end Flammarion quote>

Daikokuten at Kanzeonji Temple 観世音寺 (Fukuoka prefecture)

Japan’s oldest extant wooden statue of Daikokuten. His facial expression is fierce.

Heian Era, Important Cultural Property, Wood = Camphor 樟材, H = 171.8 cm

Source: https://dazaifubunkafureaikan.or.jp/museum/b08.html

Daikokuten at Kongōrinji Temple 金剛輪寺 (Shiga prefecture), Heian Period, Painted Wood, H = 49.9 cm

Wearing armor and holding a sword, which reminds us of Daikokuten’s origins as a Hindu god of war.

Also holding treasure bag. Source = www.kongourinji.jp/precincts and www.biwako-visitors.jp

|

Daikoku at Iwaki Jinja, Fukushima Pref.

Three rings in mallet (pear-shaped).

|

|

Daikokuten Iconography Daikokuten Iconography

Of Indian origin, Daikoku imagery in Japan is identified with the mythic Shinto figure Ō-kuninushi-no-Mikoto 大国主命 (Okuninushi-no-Kami; translated as “Prince Plenty”). His customary treasure sack is said to contain wealth, wisdom, and patience. The magic mallet in his right hand (uchide nokozuchi 打ち出の小槌) is similar to the Greek cornucopia. This mallet of plenty can miraculously produce anything desired when struck. Some Japanese say that coins fall out when he shakes his mallet. Others say believers are granted their desires by tapping a symbolic mallet on the ground three times and making a wish. Daikoku's mallet or belt is often decorated with the sacred wish-granting jewel (Skt. = cintamani; Jp. = hōjunotama 宝珠の玉), which represents the themes of wealth and unfolding possibility. This jewel, of great importance to all Buddhist traditions in both Asian and Japan, is said to grant the wishes of its holder, to pacify desires, and to bring clear understanding of the Dharma (Buddhist law). The precious jewel is also one of the seven symbols of royal power in Buddhism.

Daikoku’s magic mallet is sometimes also inscribed with icons symbolizing the male and female principles, and at other times with a pear-shaped insignia consisting of three rings (see photo at right). These symbols suggest that sexual energy can be a powerful source of wealth and prosperity. Rice, moreover, is closely associated with fertility, hence Daikoku’s common depiction standing atop two bales of rice. See story by Ryan Grube for more details and reference notes about Daikoku’s sexual symbolism.

When not appearing as part of the Seven Lucky Gods, Daikoku is often paired with Ebisu (see photos of the pair), as the two are considered father (Daikoku) and son (Ebisu). Ebisu, of Japanese origin, is the god of the ocean and fishing folk. Daikoku, or Hindu origin, is the Japanese deity of agriculture and rice. In farming communities, statues of the two are often enshrined in the kitchen. For more on Japan’s Kitchen Gods, please click here.

Modern statues of Daikoku are available for

online purchase at buddhist-artwork.com, our sister site

Sanmen Daikoku 三面大黒天 Sanmen Daikoku 三面大黒天

Daikoku also appears as the three-headed Daikoku -- Sanmen Daikoku -- for he is believed to protect the Three Buddhist Treasures (the Buddha, the law, and the community of followers). This iconography is very similar to another kitchen deity named Kōjin-sama, the Shinto kami of the kitchen. In the popular mind, Daikoku and Kōjin-sama are identical, and effigies of Daikoku placed in kitchens are thus sometimes called Kōjin.

Saichō 最澄 (767-822), the founder of Japan's Tendai sect, is credited with introducing Sanmen Daikoku to Japan. Says the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (sign in with username = guest): “A special form of Mahākāla 大黑天, having a unique body with three faces, the center being Mahākāla (Jp. Daikokuten), the left being Vaiśravaṇa 毘沙門天 (Jp. Bishamonten), and the right being Sarasvatī 辨才天 (Jp. Benzaiten). This form was created in Japan, probably around the latter half of the 14th century or later, in the Tendai school 天台宗. Legends say that when Saichō 最澄 wanted to found the Enryakuji 延曆寺 temple on Mt. Hiei 比叡山, he prayed for divine protection and assistance. In reply to his prayer, a divinity with three faces appeared and promised to grant his request: that was Sanmen daikoku. Traditionally, the protecting deity of Mt. Hiei is the deity of Mt. Miwa 三輪山, Miwa Daimyōjin 三輪大明神, who is Ōmononushi-no-mikoto 大物主尊 (cf. Hie Taisha 日吉大社 and Sannō Gongen 山王權現). There was an assimilation of Miwa Daimyōjin with Daikokuten according to the Miwa Daimyōjin Engi 三輪大明神緣起, which is dated from 1318, but based probably on a document written by Eison 叡尊 (1201-1290) in 1285. At the latest from this period onward, Daikokuten was believed as the protecting deity of Mt. Hiei. On the other hand, the idea of one deity with three faces can be traced back to the protecting yakṣa deity of the Shingon headquarters temple in Kyōto, the Tōji 東寺 (officially named Kyō-ō Gokoku-ji 教王護國寺), named Yashajin 夜叉神 or Matarajin 摩多羅神, who was constituted of Shōten 聖天 (Gaṇeśa) at the center, Dakiniten 荼吉尼天 (Ḍākinī) at the left, and Benzaiten 辨才天 (Sarasvatī) at the right, according to a work by Shukaku 守覺 (1150-1202). In the tradition of Tōji, this deity was connected to the Japanese deity Inari 稲荷, who was considered as the protecting deity of the whole temple. Thus, it is possible that the cult of Sanmen Daikoku was created in Mt. Hiei, on the basis and in competition with Yashajin of the Tōji. In the later medieval period and during the Edo period, the cult of Sanmen Daikoku as a god of fortune was very popular, and there exists many little statues of this deity in wood. [Bibliography: Hōbōgirin, 7.902b-905a; 彌永信美 (Nobumi IYANAGA), 大黒天変相 — 佛教神話学 I, Kyoto, Hōzōkan 法藏館, 2002, p. 547ff.] [n.iyanaga, Nakamura]” <end quote>

Says Butuzou.co.jp: “Sanmen Daikokuten is considered a manifestation of both Daijizaiten and Ishanaten (as a member of the 12 Deva, Daijizaiten is known as Ishanaten). As the three-headed deity, Sanmen Daikoku awards followers with wealth and virtue. In another form, this time from Esoteric Buddhism, he is a war deity who conquers evil. In his wrathful form, Sanmen Daikokuten has three faces and six arms (the skin color of each is black). He wears a blue snake as a bracelet, and a skull as a necklace. He has three eyes, and typically carries an elephant skin and sword, while grasping the hair of a Gaki 餓鬼 (Hungry Ghost) and the horns of a sheep. Sanmen Daikokuten was introduced to Japan by Saichō 最澄 (767-822), the founder of Japan's Tendai sect.” <end quote>

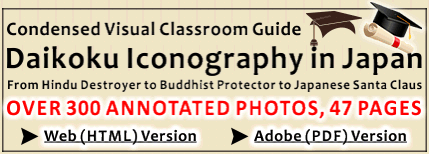

Six Forms of Daikoku

According to the 17th-century Butsuzou-su-i, there are six forms of this deity known as Roku Daikokuten 六大黒天. These forms became popular in the Edo period as bringers of prosperity. See black and white illustrations below.

- Biku Daikoku 比丘大黒, a priest, mallet in right hand, vajra-hilted sword in left. Said to be Mahādeva (the Buddha in a previous incarnation); considered a guardian of the refectory.

- Ōikara Daikoku 王子迦羅大黒, princely figure, sword in right hand and vajra in left; son of Śiva.

- Yasha Daikoku 夜叉大黒, princely figure, holds wheel of law in right hand; subduer of demons.

- Mahakara Daikoku-nyo 摩伽迦羅大黒如 or 摩訶迦羅大黑女, female, bale of rice on head; wears Chinese robe; a manifestation of the Hindu goddess Kālī, the wife of Śiva. Indeed, in esoteric cults, the Great Black Deva (Daikokuten 大黑神) is considered the masculine form of Kālī (Durgā).

- Shinda Daikoku 信陀大黒 or 眞陀大黑, boy holding wish-granting jewel (Skt = cintāmaṇi) in left hand; the jewel is a symbol of bestowing fortune

- Makara Daikoku 摩伽羅, with mallet in right hand and with bag slung over his back; stands atop a lotus leaf or (alternatively) bales of rice; the most common form in Japan; in modern times, nearly always shown standing atop two rice of bales and holding a magic mallet.

For a few more details, see Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (sign in with username = guest).

Six forms of Daikoku as drawn in the 1690 Butsuzou-su-i. Scanned from the extant copy

held by the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library. Above numerals added by website author.

RUBBING TRADITION RUBBING TRADITION

In his most popular manifestation in Japan, Daikoku is considered to be the god of success in worldly endeavors. At many temples, statues of Daikoku appear worn near the head and shoulders (see photo at right), as passersby believe that rubbing their hands on this god will somehow bring them luck (i.e., that good luck will rub off on them). This popular local belief may be an extension of earlier “rubbing” traditions, for statues of Binzuru (Pindola), the most widely revered of the Arhat in Japan, and Yakushi Nyorai, the Buddha of Medicine and Healing, are usually well worn, as the faithful rub part of the statue (knees, back, head), then rub the same part of their body, praying for the deity to heal their sickness (e.g., cancer, arthritis, headaches, other ailments). Both are reputed to have the gift of healing. The “rubbing” tradition associated with Daikoku thus suggests that Daikoku too possesses the gift of healing.

BLACK DAIKOKU

FERTILITY & PROCREATION

Daikoku is closely associated with the Brahmanic Hindu deity Mahakala, the god of war, and with Mahakala’s wife, Mahakali, the black-faced goddess of procreation often placed before Buddhist temples for protection in China and mainland Asia. The three characters in Daikoku’s name literally mean Great Black Deva, or Great Black One, and statues in Japan’s esoteric traditions often depict Daikoku with a black face (see photo at right). Daikoku’s magic mallet is sometimes inscribed with icons symbolizing the male and female principles, at other times with a jewel, and at other times with a pear-shaped insignia consisting of three rings. These symbols suggest that sexual energy can be a powerful source of wealth and prosperity. Rice, moreover, is closely associated with fertility, hence Daikoku’s common depiction standing atop two bales of rice. See story by Ryan Grube for more details and reference notes. For more on the “Great Black One,” click here.

ANIMAL ASSOCIATIONS

Rats (found where there is plenty of food). There is a curious Japanese legend about the rat and its connections with Daikoku. Writes F. Hadland Davis in Myths and Legends of Japan (first published 1913 by George G. Harrap & Company, London): ”The rat is frequently portrayed either in the bale of rice with its head peeping out, or in it, or playing with the mallet, and sometimes a large number of rats are shown. According to a certain old legend, the Buddhist Gods grew jealous of Daikoku. They consulted together, and finally decided that they would get rid of the too popular Daikoku, to whom the Japanese offered prayers and incense. Emma-O, the Lord of the Dead, promised to send his most cunning and clever oni (demon), Shiro, who, he said, would have no difficulty in conquering the God of Wealth. Shiro, guided by a sparrow, went to Daikoku’s castle, but though he hunted high and low he could not find its owner. Finally, Shiro discovered a large storehouse, in which he saw the God of Wealth seated. Daikoku called his Rat and bade him find out who it was who dared to disturb him. When the Rat saw Shiro he ran into the garden and brought back a branch of holly, with which he drove the oni away, and Daikoku remains to this day one of the most popular of the Japanese Gods. This incident is said to be the origin of the New Year’s Eve charm, consisting of a holly leaf and a skewer, or a sprig of holly fixed in the lintel of the door of a house to prevent the return of the oni.” <end quote> This story also appears in The Seven Lucky Gods of Japan by Chiba Reiko (Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1966). Chiba describes the rat as white in color (an important clue to unraveling his association with other deities who have white animal messengers), and says that in modern times, Daikoku is considered the god of five cereals, and after harvest time, farmers pay him homage for the gathering of their crops <pp. 28-30> by Chiba Reiko (Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1966). Chiba describes the rat as white in color (an important clue to unraveling his association with other deities who have white animal messengers), and says that in modern times, Daikoku is considered the god of five cereals, and after harvest time, farmers pay him homage for the gathering of their crops <pp. 28-30>

Statues of Daikoku are often paired with statues of Ebisu,

for Daikoku is considered the father and Ebisu the son.

Artwork of the pair can be found everywhere in modern Japan,

especially as members of Japan's Seven Lucky Gods.

Ebisu (Japanese origin) is the god of the ocean and fishing folk.

Daikoku (Hindu origin) is the deity of agriculture and rice.

Left Photo: Ebisu and Daikoku (bizen)

Middle Photo: Daikoku and Ebisu (bizen)

Right Photo: L to R Daikoku, Ebisu, and Hotei (bizen)

Daikoku at left, Ebisu at right (bizen)

Thanks to Robert Yellin,

the owner of the above Bizen pieces

Above: Two bizen sets taken from Yahoo auction photos

Left: Daikoko at left, Ebisu at right

Right: Ebisu at left, Daikoku at right

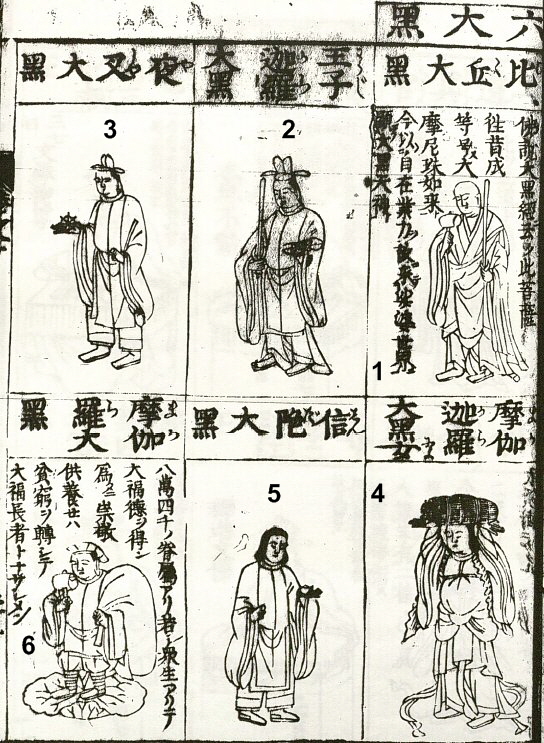

OTSU-E PAINTING OTSU-E PAINTING

COURTESY MINGEIKAN

JAPAN FOLK CRAFTS MUSEUM

Otsu-e (also spelled Otsue). Edo Period Popular Paintings of Goblins & Deities in Japanese Folk Art.

Daikoku Shaving Fukurokuju, 18th Century

Demonstrates the happy and humorous natures of these two members of the group of Seven Deities. Daikoku is the deity of prosperity, while Fukurokuju is the deity of longevity. Daikoku is almost naked, clothed only in a loincloth and wearing a red hood. Holding a razor in his right hand, he must climb a ladder in order to shave Fukurokuju's head, since it is so elongated. The painting illustrates the human qualities of deities, who seem less than godlike in such poses, showing that the immortals have as many foibles as ordinary folk.

|

Ivory Daikoku in collection of

Andres Bernhard AKA Rapick - Italy

|

|

Below Text Courtesy of JAANUS Below Text Courtesy of JAANUS

Says JAANUS: Daikokuten is generally famous as a god of luck. He is most familiar in Japan as a fat, smiling figure with a big sack over his left shoulder and a mallet in his right hand, standing on bales (tawara 俵) full of rice. He was particularly popular in the Edo period as one of the Shichifukujin 七福神. However, in India he was a warrior deity called Mahakala and was considered an emanation of Shiva (Śiva). In texts his name was transliterated as Makakara 摩訶迦羅 and translated as Daikokuten in the DAIHOUTOUDAIJITSUKYOU 大方等大集経, translated in the Zui 隋 dynasty. In Japan he appears in the outer court of the Taizoukai mandara 胎蔵界曼荼羅 (gaikongoubuin 外金剛部院) as a three faced, six-armed seated deity. According to the Dainichikyousho 大日経疏, Dainichi Nyorai 大日如来 appears as Daikokuten in order to subdue Dakiniten 荼吉尼天. However, there are no independent images of Daikoku in Japan that resemble the one in the Taizoukai mandara. It appears that Daikokuten came to be a protector of the food supply because images of him were placed in monastery kitchens in India and in China. In Japan this practice is said to have been begun by Monk Saichō 最澄 on Mt. Hiei 比叡 in the 9th century. The oldest extant image of Daikokuten in Japan is the late Heian wooden sculpture in Kanzeonji 観世音寺 in Dazaifu 太宰府 (Fukuoka prefecture) In this, his expression is fierce. In the sculpture of Myoujuin 明寿院 of Kongourinji 金剛輪寺 (Shiga prefecture; late Heian) he is shown in armor. Thus, his identity as a war god is still apparent. Later he became more closely associated with food and good forture. This tendancy was reinforced by his identification with the Shinto 神道 deity Ōkuninushi no Mikoto 大国主命. The sculpture of Saidaiji 西大寺 in Nara (Kamakura), which still displays a severe countenance and does not include the tawara was made by Zenshun 善春 on the order of Eison 叡尊 after he had a vision of Makakara. Of the many later sculptures, those of Shoujuraigouji 聖衆来迎寺, in Ootsu (1339) by Suruga Ajari 駿河阿闍利; of Hokkeji 法華寺, in Nara (1319); and that of Kojimadera 子島寺 in Nara (1609) are among those that are notable. <end quote from JAANUS>

NOTES OF CONFUSION

KUBERA, MAHAKALA, & DAIKOKUTEN, THE GREAT BLACK ONES

There are many similarities between Daikoku, Mahakala (Great Black One), and Kubera (Hindu god of wealth). In Japan, Daikoku is associated more closely with Mahakala. He is not, to my knowledge, considered a manifestation of Kubera, as some site readers have suggested. In Japan, Kubera is better known as Tamonten or Bishamonten. Kubera is the Hindu god of darkness, treasures, and wealth, and guards the north. His color is BLACK, and he is sometimes called the "Black Warrior." In India, his symbols are the flag, the jewel, and the mongoose. In Japan, his symbols are a jewel and a serpent. The Kinnaras (Kimnara) are celestial musicians with human bodies and horses' heads, officiating at the court of Kubera / Kuvera. In China, Buddhist monks claim that the Taoist deity of the Kitchens, Zao Jun, is in fact a Kinnara. In India, and Hindu legends, the Kinnaras are birds of paradise, and typically represented as birds with human heads playing musical instruments.

Daikoku and Kubera thus share the following associations -- the color black, the kitchen, and wealth. Yet, to my knowledge, in Japan, Daikoku is not known as Kubera, and Kubera is not known as Daikoku. Nevertheless, it is not impossible that some localities in Japan consider Daikoku to be a manifestation of Kubera or vice versa. However, with no concrete evidence to underpin this association, I will continue to consider Daikoku and Kubera as independent and separate deities despite their overlapping iconography. For more on Japan’s various kitchen gods, click here.

Left: Wooden statue of Daikoku (c. 1412), Hase Dera Temple, Kamakura

Middle: Same wooden statue of Daikoku (c. 1412), Hase Dera Temple, Kamakura

Right: Same wooden statue of Daikoku (c. 1412), Hase Dera Temple, Kamakura

MORE ABOUT KUBERA / KUVERA

Daikoku originates from the Hindu deity Mahakala, the “Great Black One.” Mahakala in turn may have originated from another Hindu deity named Kubera (Kuvera), the latter closely associated with the color black and wealth. The situation gets even more complicated, for Tamonten (also known as Bishamonten), the chief of the Four Heavenly Kings and the guardian of the north and winter, is also considered a primary emanation of Kubera / Kuvera. Says Meher McArthur, the curator of East Asian Art at the Pacific Asia Museum (Pasadena):

- “According to the writings of a Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, images of a seated god holding a bag of gold were placed at the doorways of monasteries and were anointed with oil by worshippers. The oil turned the statues black, and so the figures were known as Mahakala, or “Great Black One.” The bag of gold is an attribute of the Hindu deity Kubera, the God of Wealth, so the deity may have originated as Kubera. In Nepal, images of Mahakala closely resemble Kubera and may be one and the same deity. In Japan, Mahakala is worshipped as Daikoku or Makiakara-ten, the “Great Black One” in esoteric Buddhism. But since the 17th century, the deity became better known as Daikoku or Daikokuten, the God of Wealth, and one of the Seven Lucky Gods (Shichifukujin).”

<quoted from McArthur’s book “Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs & Symbols.” ISBN 0-500-28428-8, Published 2002 by Thames & Hudson. Click here to view or buy book at Amazon. >

- Kubera (Kuvera), the Hindu god of wealth and buried treasure, is sometimes considered the king of the Yaksha. Yaksha are powerful earth deities. They guard the world's wealth, such as gold and silver. In the same book, Meher McArthur says this:

“In Tibet and Nepal, Vaishravana (Jp. = Bishamonten / Tamonten) is closely related to the God of Wealth, Kubera, who is considered to be his most important manifestation. It is possible that Vaishravana is the Buddhist form of the earlier Hindu deity, Kuvera, who was the son of an Indian sage, Vishrava, hence the name, Vaishravana. According to Hindu legend, Kubera performed austerities for a thousand years, and was rewarded for this by the greator god, Brahma (Jp. = Bonten), who granted him immortality and the position of God of Wealth, and guardian of the treasures of the earth. As Vaishravana, this deity also commands the army of eight Yasha (Jp. = Yaksa), or demons, who are believed to be emanations of Vaishravana himself. The most important of these eight are the dark-skinned Kuvera of the north and the white Jambala of the east. Each of these emanations holds a mongoose that spews jewels. In Tibet and Nepal, he is worshipped as the God of Wealth in all three manifestations: Vaishravana, Kubera, and Jambala. In many Tibetan and Nepalese images of Kubera, the deity is shown as a plump figure wearing a crown, ribbons and jewelry, and holding a mongoose, representing this god’s vistory over the naga (snake deities), who symbolize greed. As God of Wealth, Vaishravana (aka Kubera) squeezes the mongoose and causes the creature to spew out jewels.”

Mahākāla-deva

Says the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (sign in with username = guest): “An important Tantric dharmapāla, considered to be a fully enlightened buddha. He is the Buddhist form of the Hindu god Śiva, taken into the Buddhist pantheon at the beginning of the second millennium C.E. As a dharmapāla, he provides protection from negative elements. Thus, despite his exalted status, Mahākāla is seen placed above temple doors, alongside and even below lesser deities. The Chinese pilgrim Yixing (671-695) reported seeing Mahākāla so placed in Indian temples, holding a bag of gold, which indicates that Mahākāla has long been associated with Kubera, the god of wealth. Mahākāla is largely a Tibetan and Mongolian deity, never having gained wide popularity in China. The Japanese form is likely to have entered from Mongolia, where he was introduced by the third Dalai Lama in the sixteenth century. In Tibetan iconography Mahākāla is often seen in a triumvirate with Mañjuśrī and Avalokitêśvara. The Tibetan pantheon includes over seventy forms of the god, both of Indic and Tibetan innovations. Among these some are considered world-transcendent, some worldly deities. His most commonly represented form is the six-handed ṣad-bhuja 六臂 Mahākāla. Reference=[Mikkyō Daijiten, 1453c]. Transliterated as 摩訶迦羅 (or 摩訶謌羅). [h.adams]”

“The great black deva 大黑神. Two interpretations are given. The esoteric cult describes the deva as the masculine form of Kālī, i.e. Durgā, the wife of Śiva; with one face and eight arms, or three faces and six arms, a necklace of skulls, etc. He is worshipped as giving warlike power, and fierceness; said also to be an incarnation of Vairocana for the purpose of destroying the demons; and is described as 大時 the “great time” (-keeper) which seems to indicate Vairocana, the sun. The exoteric cult interprets him as a beneficent deva, a Pluto, or god of wealth. Consequently he is represented in two forms, by the one school as a fierce deva, by the other as a kindly happy deva. He is shown as one of the eight fierce guardians with a trident, generally blue-black but sometimes white; he may have two elephants underfoot. Six arms and hands hold jewel, skull cup, chopper, drum, trident, elephant-goad. He is the tutelary god of Mongolian Buddhism. [J. Daikoku; M. Yeke-gara; T. Nag-po c'en-po, CMuller; Soothill, Hirakawa].” <end quote from DDB>

Wood statue of Daikoku in collection of site author

Early 20th century

SOURCES

- Butsuzō zui 仏像図彙 (Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images). Published in 1690 (Genroku 元禄 3). A major Japanese dictionary of Buddhist iconography. Hundreds of black-and-white drawings, with deities classified into categories based on function and attributes. For an extant copy from 1690, visit the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library. An expanded version, known as the Zōho Shoshū Butsuzō-zui 増補諸宗仏像図彙 (Enlarged Edition Encompassing Various Sects of the Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images), was published in 1783. View a digitized version (1796 reprint of the 1783 edition) at the Ehime University Library. Modern-day reprints of the expanded 1886 Meiji-era version, with commentary by Ito Takemi (b. 1927), are also available at this online store (J-site). In addition, see Buddhist Iconography in the Butsuzō-zui of Hidenobu (1783 enlarged version), translated into English by Anita Khanna, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 2010.

- Handbook on Viewing Buddhist Statues 仏像の見方ハンドブック. By Ishii Ayako. A wonderful book. Published 1998. Japanese Language Only. 192 pages; 80 or so color photos. ISBN 4-262-15695-8.

- JAANUS. Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. A wonderful online dictionary compiled by the late Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent. It covers both Buddhist and Shinto deities in great detail. Over 8,000 entries. Written in English, yet presenting all key terms in Japanese.

- Buddhism (Flammarion Iconographic Guides)

, by Louis Frederic, Printed in France, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. A highly illustrated volume, with special significance to those studying Japanese Buddhist iconography. Includes many of the myths and legends of mainland Asia as well, but its special strength is in its coverage of the Japanese tradition. Hundreds of accompanying images/photos, both B&W and color. , by Louis Frederic, Printed in France, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. A highly illustrated volume, with special significance to those studying Japanese Buddhist iconography. Includes many of the myths and legends of mainland Asia as well, but its special strength is in its coverage of the Japanese tradition. Hundreds of accompanying images/photos, both B&W and color.

- Essentials of Buddhist Images: A Comprehensive Guide to Sculpture, Painting, and Symbolism. By Kodo Matsunami. Paperback; first English edition March 2005; published by Omega-Com. Above clipart in left column scanned from this book. Matsunami (born 1933) is a Jōdo-sect 浄土 monk, a professor at Ueno Gakuen University, and chairperson of the Japan Buddhist Federation. He received the government's Medal of Honor (褒章 hōshō), Blue Ribbon, for his achievements in public service. Says Matsunami: “Bishamonten protects from disaster and bodily harm. Daikoku satisfies the deisre for food. Benzaiten represents sexual desire. Hotei brings laughter, and Ebisu grants wealth.

- Tobifudo Deity Dictionary. Ryūkozan Shōbō-in Temple 龍光山正寶院 (Tokyo). Tendai Sect.

- Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (sign in with username = guest)

- The Seven Lucky Gods of Japan

, by Chiba Reiko. Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1966. Also see UCLA Center for East Asian Studies, Educational Resources from teacher Samantha Wohl, Palms Middle School, Summer 2000. See Wohl’s Materials List (based on Chiba Reiko’s book). , by Chiba Reiko. Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1966. Also see UCLA Center for East Asian Studies, Educational Resources from teacher Samantha Wohl, Palms Middle School, Summer 2000. See Wohl’s Materials List (based on Chiba Reiko’s book).

LEARN MORE

田の原大黒天 (Tanohara Daikokuten)

Lit. “Origin-of-the-Rice-Paddy Daikokuten.” See below photo.

This is a side page.

Return to Seven Lucky Gods Main Page

|

|