|

|

|

|

MANDALA IN JAPAN - INTRO MANDALA IN JAPAN - INTRO

MANDALA or MANDARA 曼荼羅

Especially important to Japan’s Esoteric Sects

Origin = India

Sanskrit = Maṇḍala, मण्डल

Chinese = Màntúluó

Japanese = Mandara

English = Mandala

The mandala, Hindu in origin, is a graphic depiction of the spiritual universe and its myriad realms and deities. Much later, first in Tibet and China then Japan, the mandala was adopted as a powerful religious icon among practitioners of Esoteric Buddhism (Skt. = Vajrayana). In Japan, the mandala rose to great prominence as a “living entity,” one that ensured the efficacy of esoteric rituals performed in its presence. The original Sanskrit term “maṇḍala” comes from India, and is sometimes translated as circle, essence, or hitch (as when connecting an ox to a cart). The Sino-Japanese spelling of mandala (曼荼羅 or 曼拏羅 or 曼陀羅) is a transliteration of the Sanskrit term. But these transliterations have no inherent meaning -- they simply resemble the sound of the original Indian term.

Mandala scrolls and paintings became popular in Japan in the 9th century onward with the growth of the Shingon 真言 and Tendai 天台 sects of Esoteric Buddhism (Jp. = Mikkyō 密教; Skt. = Vajrayana), which arose in part as a reaction against the power and wealth of court-sponsored Buddhism. The founders of Esoteric Buddhism in Japan were the monks Kūkai 空海 (774 - 835 AD) and Saichō 最澄 (767 - 822 AD). Kūkai, aka Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師 (his posthumous name), founded the Shingon Sect of Esoteric Buddhism, while Saichō founded the Tendai Sect. Both traveled to China to study and learn the esoteric secrets, and both returned to Japan with numerous artworks and sutras to help spread the teachings. Yet, the oldest surviving color mandala in Japan is thought to be a copy of the Ryōkai Mandara (from China) which was brought to Japan in 859 AD by the Tendai priest Enchin 円珍 (814-891). See below photo.

Ryōkai Mandala or Two World Mandala Ryōkai Mandala or Two World Mandala

The most widely known mandala form in Japan is the Ryōkai Mandala 両界曼荼羅, translated as the Two World Mandala. Sometimes also pronounced as Ryōgai Mandala or spelled Ryokai or Ryoukai. It is composed of two separate mandala, which together represent the central devotional image of Esoteric Buddhism in Japan.

- Taizōkai 胎蔵界曼荼羅 or Womb World Mandala. Sanskrit = Garbhadhatu. Based on the Dainichikyō 大日経 Sutra. Also spelled Taizoka or Taizoukai.

- Kongōkai 金剛界曼荼羅 or Diamond World Mandala. Sanskrit = Vajradhatu. Based on the Kongōchōkyō 金剛頂経 Sutra. Also spelled Kongokai, Kongoukai.

The Taizōkai Mandala (Womb World) is associated with ultimate principle (ri 理) and the Kongōkai Mandala (Diamond World) with mind or intelligence (chi 智). Says the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (sign in with user name = guest): “The two realms are fundamentally one, as are the absolute and phenomenal, e.g. water and wave. The Garbhadhātu (Womb World) representing the 理 and the 因 (principle and cause), the Vajradhātu (Diamond World) the 智 and the 果 intelligence/reason and the effect, i.e. the fundamental realm of being, and mind as inherent in it 胎 and 金剛.” <end DDB quote>

Even today, in many Japanese Shingon and Tendai temples, two large mandalas are typically mounted on wooden screens at right angles to the axis of the image platform. The mandala on the east side is the Kongōkai Mandala, and the mandala on the west side is the Taizōkai Mandala. The Kongōkai Mandala represents the cosmic or transcendental Buddha (aka Dainichi Nyorai and complete wisdom), while the Taizōkai mandala represents the world of physical phenomenon and ultimate principle (see below for details).

Most scholarship to date describes the mandala as functioning as a powerful aid in meditation, concentration, and “inner visualization” exercises among Japan’s esoteric practitioners. However, this orthodox view has been challenged and cast into doubt by contemporary scholars such as Robert H. Sharf and Cynthia Bogel. Both argue that the prevailing view is faulty and unsupported by ritual texts. Says Sharf (p. 9): “Contrary to virtually everything written on the subject, mandalas did not serve as aids to ritual visualization, nor could they have; the mandalas are better viewed as living entities necessary to ensure the efficacy of the rites performed in their presence.” In the same book (p. 197), Sharf says “It should now be clear that speculation as to the conception and function of Buddhist mandalas -- and indeed all Buddhist religious icons -- is of limited value unless predicated on the critical analysis of their ritual and institutional deployments.”

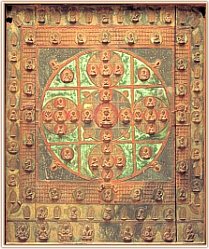

Kongōkai (Diamond World)

National Treasure, Heian Period, 9th C

Kyōōgokoku-ji 教王護国寺 Temple (Tōji 東寺)

From temple catalog |

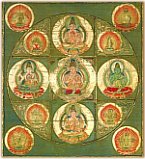

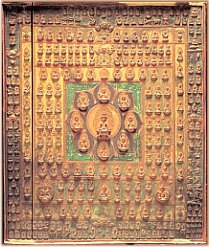

Taizōkai (Womb World)

National Treasure, Heian Period, 9th C

Kyōōgokoku-ji 教王護国寺 Temple (Tōji 東寺)

From temple catalog |

|

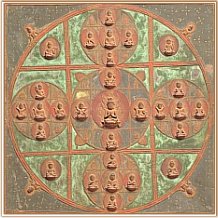

Closeups of above Kongōkai Mandala

Image in center is Dainichi Nyorai

Closeup from Kongōkai (Diamond) Mandala

Image in center is Dainichi Nyorai

Kyōōgokoku-ji 教王護国寺 Temple (Tōji 東寺), Heian Period, 9th C

North (Top) = Fukūjōju (Fukujoju) | South (Bottom) = Hōshō (Hosho)

Left (West) = Amida | Right (East) = Ashuku

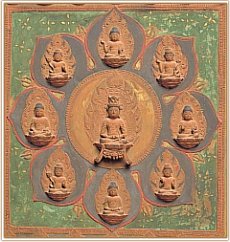

Most Shingon and Tendai temples display a mandala depicting Dainichi Nyorai, the central Buddha of worship in Esoteric Buddhism, surrounded by four other Buddhas. This grouping of five is known as the Gochi (or Godai) Nyorai 五大如来, and may be translated as the “Five Tathagata” or the “Five Buddha of Wisdom.”

For details on significance of #5, click here

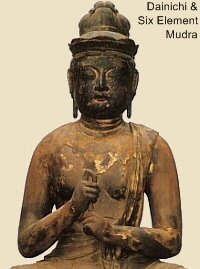

SIX ELEMENTS 六界 SIX ELEMENTS 六界

Jp. = Rokukai ろくかい

In Esoteric Buddhism, the five elements (Jp. = Gogyo, Gogyō 五行) are combined with one additional element, the MIND, for a total of six. Statues or paintings of Dainichi Buddha, the central deity of Esoteric Buddhism in Japan, often portray Dainichi with a characteristic hand gesture called the Mudra of Six Elements (Chiken-in 智拳印), in which the index finger of the left hand is clasped by the five fingers of the right. This mudra symbolizes the unity of the five worldly elements (earth, water, fire, air, and space) with a six element, spiritual consciousness. Others equate the left hand with the male organ and the right hand with the female organ, and maintain that it represents, by means of sexual symbolism, the central deity of the mandala from which all the other deities emanate. According to another interpretation, the left hand represents sentient beings and the right hand the Buddha, and thus symbolizes the two-way response of the Buddha and sentient beings.

In the Mandala artform, which is of special importance to Japan’s Esoteric sects (Shingon, Tendai), the five elements are considered inanimate (this equates to the Garbhadhatu or Womb World Mandala). Only by adding the sixth element -- mind, perception, or spiritual consciousness -- do the five become animate. This equates with the Vajradhatu or Diamond World Mandala. Phrased differently, there is “unity” only when the sixth element is added. Without the sixth element, ordinary eyes see only the differentiated forms or appearances.

- Earth

- Water

- Fire

- Air (or Wind)

- Space

- the MIND (spiritual consciousness or perception)

Daniel J. Boorstin (see his book The Discovers)

The Buddhist inclination for multiplying images.

“Buddhist monasteries were especially active in experimenting with ways of multiplying images, for the very heart of Buddhism, as historian Thomas Francis Carter observes, was “the duplicating impulse.” Just as the faithful themselves were to become replications of the Buddha, so too the devout Buddhist attained “merit” by multiplying images of Buddha and of the sacred texts. Buddhist monks carved images in stone and then took rubbings from them, they made seals, they tried stencils on paper, on silk, and on plastered walls. They made small wooden stamps with handles from which they made primitive woodcuts. In Japan commercial publishing grew out of temple publishing.” <end quote from Daniel J. Boorstin>

|

|

|

Detail from Taizokai (Womb World). The Ryokai Mandara is the oldest color mandala still in existence in Japan. It is believed to have been a copy made in China and brought to Japan in 859 AD by the Tendai priest, Enchin. Photo courtesy of Washington State University.

Photo Courtesy of:

Ancient Japan Gallery

|

|

DAINICHI NYORAI DAINICHI NYORAI

Cosmic Buddha and Mandalas

Below text courtesy Ancient Japan Gallery

Esoteric Buddhism was founded on the principle that the two aspects of Buddha, both the unchanging cosmic principle and the active, physical manifestation of Buddha in the natural world, were one and the same. The truth of the cosmic order, which is contained in the relationships between the Cosmic Buddha and all his worldly manifestations, cannot be known verbally.

One method for understanding this truth was to comprehend it visually and symbolically; to this end, Japanese esoteric Buddhists imported the mandala (in Japanese, mandara), or circle, to express symbolically the order of the universe related to the cosmic Buddha. Since the Buddha occupied two separate realms, the mandala form that the esoteric priests imported was the Mandala of the Two Worlds, or Ryoukai Mandara (Ryo=two, kai=world, mandara=mandala). On the east side of the temple would be placed the Diamond World (Kongoukai in Japanese, Vajradhatu in Sanskrit), which represented the world of the transcendental Buddha. It was called the Diamond World because it embodied a static, crystal clear, and adamantine truth of the universe. In the Diamond World, the Cosmic Buddha (DAINICHI NYORAI in Japanese), sits in the center of assemblies of Buddhas arranged in a three by three square.

The other world, the Womb World (Taizoukai in Japanese, Garbhadhatu in Sanskrit), was the world of physical phenomenon. In this mandala, the Dainichi Nyorai sits in the middle in relationship to all his physical manifestations ranged in several courts radiating outward from him. In the detail here, we see nine physical manifestations from the Lotus Holder's Court (which sits on the right side of the Court of Eight Petals, which is the court of the Cosmic Buddha). The physical manifestations of the Lotus Holder's Court represent the purity of all things. In the picture, you can see Buddha in several different aspects. To the bottom right, he is a three-headed, angry creature that represents the Buddha's ability to overcome evil (the three heads symbolize vigilance over evil). Most of the Buddhas, however, represent compassion or mercy. Not only are all the Buddhas surrounded by unique symbols, each one has a unique pairing of hand gestures, called mudras. The mudras (hand gestures) are key in Buddhist practice; they recreate hand gestures from the life of Buddha. Not only did Buddha teach in words, he taught symbolically in hand gestures. Like all Buddhist art, a large part of the symbolic meaning is located in these hand gestures. For instance, the middle figure is making the semuiin gesture with his right hand (in Sanskrit, abhayamudra ). This means "fear not." Yes, an esoteric devotee could name each and every hand gesture in the picture you're looking at!

An esoteric devotee would be asked to starre and meditate on each of these Buddhas in turn. He would meditate on their symbolic meaning as it is represented visually and he would meditate on that deity's relationship to the other deities as those relationships are represented visually. When he's finished with the Taizoukai Mandara, he would move on to the Kongoukai Mandara. Once he's meditated and, through visual and symbolic understanding, come to comprehend all the Buddhas and their relationships across the two worlds, he will have unified himself with the Cosmic Buddha. Beginning priests would be asked to throw a blossom at each of the two mandalas; the deity that the blossom landed on would be adopted as that person's personal deity for the course of his study. <end text from Washington State Univ.>

NOTE FROM SITE EDITOR: The view expressed in the paragraph above is now contested. The above view describes the mandala as functioning as a powerful aid in meditation and “inner visualization” exercises. However, this view has been cast into doubt by contemporary scholars such as Robert H. Sharf and Cynthia Bogel. Both argue that the prevailing view is faulty and unsupported by ritual texts. Says Sharf (p. 9): “Contrary to virtually everything written on the subject, mandalas did not serve as aids to ritual visualization, nor could they have; the mandalas are better viewed as living entities necessary to ensure the efficacy of the rites performed in their presence.”

MANDALA PROTECTORS

Han'nya Bosatsu 般若菩薩

(Sanskrit = Prajnaparamita Bodhisattva)

This entry has moved to a new location.

Below Text Courtesy of Miho Museum (Japan)

www.miho.or.jp/booth/html/doccon/00000619e.htm

The pair of mandalas known as the Ryoukai Mandalas are the central devotional images of the Esoteric sects of Buddhism -- namely the Taizoukai, or Womb World Mandala (Garbhadhatu Mandala) based on the Dainichikyo sutra, and the Kongoukai, or Diamond World Mandala (Vajradhatu Mandala), based on the Kongochokyo sutra. These two sutra texts emerged at different stages in the development of Esoteric Buddhism in India. It was Hui-kuo (746-805), the teacher of Japanese Priest Kuukai (774 - 835 AD; also called Kobo Daishi, the founder of Japan’s Shingon Sect of Esoteric Buddhism), who combined this pair of mandala images based on these two sutras. Strictly speaking, the formal name of the Taizoukai mandala in Japanese is "Daihitaizo Sho Mandara," omitting the character "kai" for world, but starting around the 9th century, during the lifetime of the major Tendai sect master, An'nen, the "kai" character was added to match the "kai" found in the name of the Kongoukai mandala.

|

Ryōkai Mandalas

Kongōkai - Diamond Mandala

Muromachi Era, 14th & 15th C.

Hanging scroll, color on silk

Dimension H-138.5 W-122.2

|

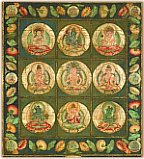

Ryōkai Mandalas

Taizōkai - Womb World Mandala

Muromachi Era, 14th & 15th C.

Hanging scroll, color on silk

Dimension H-138.5 W-122.2

|

|

Photos courtesy of Miho Musuem

www.miho.or.jp/booth/html/doccon/00000619e.htm

|

|

The museum writes: Priest Kūkai (774 - 835 AD) brought back Japan's first images of these two mandalas from China, and these two mandalas are called the Konpon Mandalas, or root mandalas. The lineage of mandalas based on these Konpon Mandalas are known as "Genzu," or "original image," mandalas. The Takao Mandalas and the Konpon Mandalas at Toji Temple are considered the representative examples of these Genzu mandalas. Since Kuukai, however, mandala images from other lineages have been brought back to Japan from China. The Sai-in Mandalas of Toji Temple are based on the mandala iconography brought back by Enchin, and they differ slightly from the Genzu iconography. Mandalas considered to be from the Tendai lineage, such as the Shitennoji Mandala and the Taisanji Mandala, are clearly from a non-Genzu lineage.

In the present work, memorial altars have been placed in front of the Thousand-Armed Kannon (Avalokitesavara-sahasrabhuja-locana) and Kongo-zoo Bosatsu (Daimond Bosatsu, Stottarasata-bhuja-vajra-dhara) on either side of the Kokuzoin section (lower section of the composition), and this is characteristic of a Tendai lineage mandala pair, as opposed to the Genzu lineage. The Tendai lineage iconography, however, frequently exchanges the positions of the eastern directional Buddha and the northern directional Buddha in the Chudai-hachiyo-in (central eight-petal court or center of the composition), and in the present work the deities are placed in their Genzu image positions. While the Kongoukai normally consists of ku-e, or 9 precincts, the spikes of the vajra staffs which are supposed to be painted behind the various deities in the Misai-e (the lower right as the viewer faces the mandala) are not visible here, and this may represent an abbreviation of the original iconography over time.

In any event, this pair is unquestionably a Ryoukai Mandala pair that differs from the Genzu lineage. In terms of period of production, the rough weave of the ground silk and the relatively rough and formalized depiction of the various deities suggest a date in the first half of the Muromachi period for the pair. <End quote from Miho Museum in Japan>

BELOW

More Mandala Photos

|

|

|

|

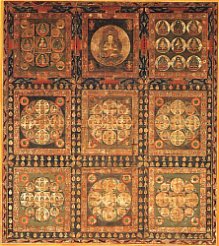

Kongōkai - Diamond Mandala

Jizō-in Temple

Source and date unknown

|

CLOSEUP of Kongōkai Mandala

Jizō-in Temple

Source and date unknown

|

|

|

|

|

Taizōkai - Womb World

Jizō-in Temple

Source and date unknown

|

CLOSEUP of Taizōkai Mandala

Jizō-in Temple

Source and date unknown

|

|

Above four photos

Source and Date Unknown

Photos found on web, but no longer able to access site

|

|

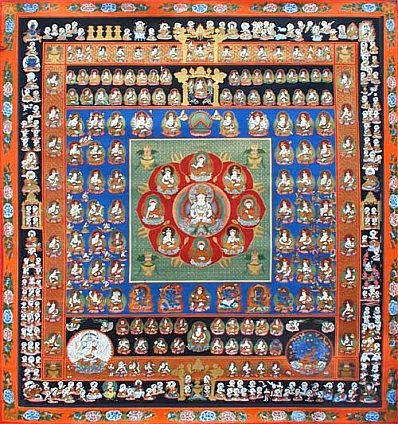

Taizoukai Mandala (Sanskrit Garbhadhatu)

Original painting, Japan, Kamakura Era, 13th - 14th century

47.6 x 24.5 inches / 119 x 98,7 cm

Photo from www.thangka.de/Gallery-3/Cosmos/9-6/garbhadatu-1.htm

Vajrasattva (Common Mandala Deities)

Four Diamond Bodhisattavs [Jap.: "kongo-bosatsu"]

Istavajra [Jap. Yokukongo, "Desire Diamond"]

Kelikilavajra [Jap. Sokukongo, "Contact Diamond"]

Ragavajra [Jap. Aikongo, "Love Diamond"]

Manavajra [Jap. Makongo, "Pride Diamond"]

Consorts [Four diamond Apsaras, Jap. shi-kongo-nyo]

Istavajrini [Jap. Yokukongonyo, "Disire Diamond Apsara"] Southeast

Kelikilavajrini [Jap. Sokukongonyo, "Contact Diamond Apsara"] Southwest

Ragavajrini [Jap. Aikongonyo, "Love Diamond Apsara"] Northwest

Manavajrini [Jap. Mankongonyo, "Pride Diamond Apsara"] Northeast

The consorts symbolize the four Paramitas

and carry the attributes of the four outer Offering Bodhisattvas

Source for Above Names: www.thangka.de

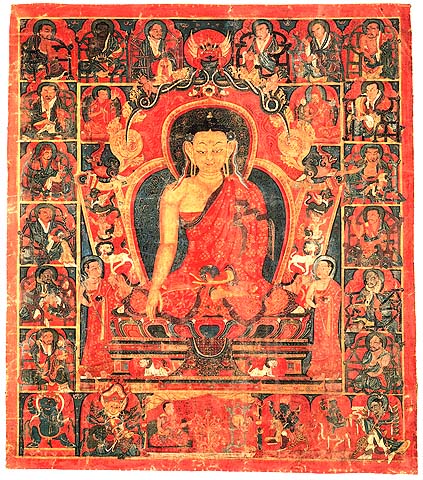

Arhats (of Theravada Buddhism)

Unidentified (most likely not Japanese mandara)

For hundreds of Arhat mandalas, please visit:

www.tibetart.org/search/set.cfm?setid=108&page=1

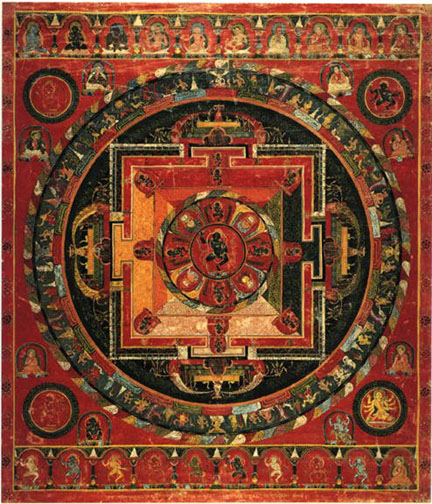

Tibetan Mandala (51.5 x 44.6 cm)

Nairatma Mandala - Hevajra Mandala

Central Tibet, 16th century (second half)

Photo courtesy of www.asianart.com/mandalas/mandimge.html

LEARN MORE

SOURCES

Last Revision = Oct. 24, 2011

Last Revision = Feb. 21, 2011

|

|