|

|

|

|

Hachiman & Hachimangū Shrines

Shintō Kami, Protector of Warriors and Community at Large.

God of Archery & War, Patron of Writing & Culture.

Shintō Deity (Kami) Who Adopted Buddhism, aka

Hachiman Daibosatsu 八幡大菩薩 (Great Bosatsu Hachiman).

UPDATE June 2015: Hachiman’s Initial Rise to Prominence,

by scholar Bernhard Scheid, Japan Review 27 (2014): 31–51.

THIS IS A SIDE PAGE

Return to Shintō Shrine Guide

Hachimangū Shrines 八幡宮 are devoted to the Shintō deity (kami 神) Hachiman 八幡, but some also venerate the lengendary 3rd-4th century emperor of Japan, Emperor Ōjin 応神 (Ojin), who was identified with Hachiman around the 9th century. The Hachiman cult can be traced back to the late 6th century at Usa Hachimangū 宇佐八幡宮 shrine in Ōita Prefecture, where the deity played an oracular function and exhibited attributes of both Shintō animism and Korean shamanism. It was only later, sometime in the 9th century, that the deity became associated with Emperor Ōjin, and later still that Hachiman became worshipped as the god of archery and war, ultimately becoming the tutelary deity of the Minamoto clan and its famed warrior Minamoto Yoritomo 源頼朝 (1147-1199), founder of the Kamakura shogunate.

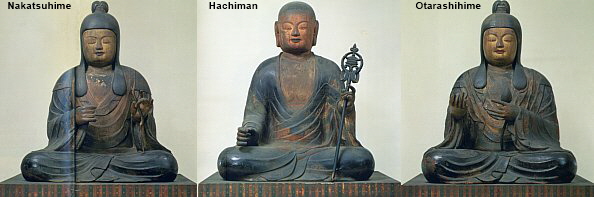

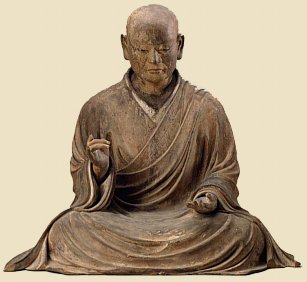

PHOTOS AT RIGHT. Among the earliest statues of Hachiman in Japan, these pieces served as prototypes for the subsequent development of Hachiman statuary.

Hachiman can also be read YAWATA. It literally means “eight banners” or “eight banderoles,” which supposedly fell from heaven in legends involving the birth of Emperor Ōjin. Important early Hachimangū shrines deify Emperor Ōjin, Ōjin’s mother Empress Jingū 神功, and Ōjin’s wife Himegami 比売神 (aka Nakatsuhime 仲津姫, Ōjin’s spouse depicted as a deity). From the late 8th century, Hachiman was also considered a Bodhisattva, and thus served as protector in both Shintō and Buddhist traditions. Extant artwork of this Shintō deity often shows him dressed in the garb of a Buddhist monk -- thereby symbolizing his acceptance of Buddhism and clothing him in the syncretic Kami-Buddha matrix that defined most of Japan’s religious history.

Today there are approximately 30,000 Hachimangū shrines nationwide, with the head shrine at Usa Hachimangū in Ōita -- where Ōjin (Ojin), Jingū (Jingu), and Himegami were first enshrined. The Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine 鶴岡八幡宮 in Kamakura is another prestigious Hachiman shrine. The latter was moved to its current location in 1183 by Minamoto Yoritomo, Japan’s first Shōgun (Shogun) 将軍, who had seized power from the emperor and nobility, established the shogunate (military government) in Kamakura in 1185, and adopted Hachiman as the tutelary deity of the new warrior class. Based on period records, Ōjin’s symbolic animal and messenger is the dove. This iconography is maintained by the Tsurugaoka Hachimangu shrine in Kamakura, where the name board atop its foremost shrine building includes two doves (which form the character HACHI 八 (see photo at right). The architecture of Hachimangū shrines (Hachiman Zukuri 八幡造) is also distinct. See JAANUS for details. Hachiman is also considered the the patron god of writing and culture, for Ōjin (the fifteenth emperor of Japan according to the Kōjiki), invited Korean and Chinese scholars to educate his son and courtiers in the ways of the world.

Metamorphosis of a Diety: The Image of Hachiman in Yumi Yawata

Story by scholar Ross Bender, appearing in the Summer 1978 edition

of the Monumenta Nipponica, Volume XXXIII, Number 2. Pages 165-178.

Bender explores the development of the Hachiman cult in Japan, pointing out that Hachiman’s role as deity of the Minamoto clan and deity of the warrior class was a comparatively late development. In the first phase, near the end of the sixth century, Usa Hachimangū 宇佐八幡宮 shrine in Ōita Prefecture (northeast Kyushu) was the center of the Hachiman cult, and the deity played an oracular function. By 750 AD the shrine enjoyed great power and prestige, and the pronouncements of its medium had great impact on state affairs. The deity was essentially an amalgamation of Shinto animism and Korean shamanism. In the second phase, beginning in the late 8th and early 9th centuries, Hachiman was awarded the status of Bodhisattva, and became a guardian deity, a protector god, in the Buddhist pantheon. He was known as the Great Bodhisattava Hachiman (Hachiman Daibosatsu 八幡大菩薩). In the mid-9th century, the Iwashimizu Hachimangū 石清水八幡宮 shrine was built at Otokoyama, south of Kyoto, to bring Hachiman closer to Kyoto to protect the emperor. During this period, Hachiman is also associated with the sovereigns Jingū and Ōjin, perhaps, says Bender, “to integrate the god more closely with the imperial institution by making him an imperial ancestor.” In the third phase, around the end of the 12th century, Hachiman was adopted by the Minamoto clan as their tutelary deity and guardian deity of the warrior class.

|

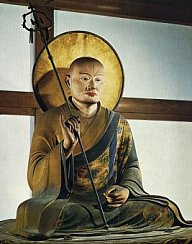

Hachiman 神道の神様八幡 (by Kaikei)

Hachiman as a Buddhist Monk.

Painted Wood. H 87 cm. Dated +1202.

Todaiji (Tōdaiji) Temple 東大寺.

Photo Courtesy Temple Catalog.

|

|

More on Hachiman from scholar Ross Bender: More on Hachiman from scholar Ross Bender:

- See Bender’s 1980 dissertation for Columbia University entitled "The Political Meaning of the Hachiman Cult in Ancient and Early Medieval Japan.

- Says Bender in the Premodern Japanese Studies Forum* “It should be kept in mind that Hachiman was and is a Shinto deity and that while the kami manifests in various guises, fundamentally Hachiman is a Shinto kami. The Tamukeyama Hachiman 手向山神社 shrine to the east of Todaiji Temple is not as well-known as it might be, but it is the guardian deity of Todaiji and the Nara Daibutsu 奈良大仏 (Big Buddha of Nara). Although its present location dates from 1237, it is the heir of the shrine built when Hachiman came to Nara in Tempyo Hoji 1 (8th century). The shrine festival is the Tegai-e 手掻会 (or Tenkai-e 転害会), held on October 5, and I believe it is the only time the famous statue of Sogyo Hachiman (see photo at right) in the Hachiman-den on the Todaiji grounds is available for viewing. The shrine itself should not be missed although often is when visiting Nara. Some recent photos of the shrine are here.” <end quote from Bender>

|

Sōgyō Hachiman 僧形八幡

Lit. = Hachiman in the form of a monk.

Tōdaiji Temple, Nara, by Kaikei, 1201 AD, H = 87 cm. Photo: Web-Japan

|

|

More on Tōdaiji Temple’s Famous Statue More on Tōdaiji Temple’s Famous Statue

Says Web-Japan.org: “Hachiman is a popular Shintō deity who protects warriors and looks after the people's well-being. He has been one of the most widely revered deities in Japan since the Nara period, claiming much respect from both the high-placed and the lowly. Already since the early Heian period he was sometimes sculpted as a deity in the guise of a Buddhist monk (Sōgyō Hachiman 僧形八幡). Some say he is Bishamonten, the Buddhist deity of war and protector of Buddhism, in disguise.

It is known from an ink inscription found inside the hollow body that this image was made by Kaikei in 1201 as the main object of reverence at Hachimangu Shrine, which was built near Tōdaiji Temple (Nara) to give it added divine protection. At first glance it looks like a sculpture of a high-ranking Buddhist priest, but the halo 光背 (kōhai) behind it indicates that it is the image of a deity. The general atmosphere is one of solemnity. The clothing is represented in a simple way and the original colors are still vivid and attractive.” <end quote from Web-Japan.org>

Sōgyō (Sogyo) Hachiman 僧形八幡

Courtesy JAANUS: “One of the most popular Shinto deities, who is shown in the form of a Buddhist monk and who protects warriors and the community at large. Sometimes identified as the Emperor Oujin 応神 and accompanied as a statue by Oujin's mother Jinguu 神功 and Nakatsuhime 仲津姫, his spouse as a deity. The first extant sculptures of Hachiman date from the late 9th century (Kyouougokokuji Temple 教王護国寺, aka Touji Temple 東寺 in Kyoto), and from these through to images of the Heian period, he is always shown with a shaven head in the robes of a monk. Typically he is holding the cane of a monk (shakujou 錫杖) and is seated on a pedestal. The reason for this pose is obscure, though several suggestions have been made. One is that he was intended to resemble Amida 阿弥陀 but his identification with Amida is only known from a later time. Another idea is that he was made to look like Jizou 地蔵 but his cult was not connected with that of Jizou. The most plausible suggestion is that his appearance as a monk reflects the sincerity of his adoption of Buddhism. From the late 8th century, Hachiman was called Great Bodhisattava Hachiman (Hachiman Daibosatsu 八幡大菩薩). Hachiman's appearance at this time is perhaps less remarkable given that at the time many nobles were becoming monks and nuns. Sōgyō Hachiman were being made even after the Heian period, and by the 13th century other Shinto gods (kami 神) were also shown as Buddhist monks in paintings.” <end JAANUS quote>

9th Century, Sōgyō Hachiman Shin 僧形八幡神 and Joshinzasō 女神座像

Hachiman in the form of a monk, with two Shintō Goddesses

Treasures: Chinjū Hachimangū Shrine 鎮守八幡宮, which protects

Kyōōgokokuji Temple 教王護国寺 (aka Tōji Temple 東寺) in Kyoto

Center: Hachiman H = 109.9 cm; Left Himegami 比売神 (aka Nakatsuhime 仲津姫, Ōjin’s spouse)

Right Ōtarashihime 大帯姫 (Jingūgōgō 神功皇后)

Painted Wood 彩色像, Designated National Treasures, PHOTO: Temple catalog

9th C., Sōgyō Hachiman Shin 僧形八幡神 and Joshinzasō 女神座像

Hachiman in the form of a monk, with two Shintō Goddesses

Treasures: 休ケ岡八幡宮, a shrine protecting Yakushiji Temple (Nara)

Painted Wood, Center Hachiman H = 38.8 cm, Designated National Treasure

Left Jingūgōgō 神功皇后 and Right Nakatsuhime 仲津姫命, Height 36.1 cm

PHOTO: Yakushiji Temple

11th Century, Sōgyō Hachiman Shin 僧形八幡神 and Joshinzasō 女神座像

Treasures: Natagu Shrine 奈多宮, Oita Prefecture

Center Hachiman, Wood, Height 54.2 cm, Ichiboku Zukuri Technique

Left Jingūgōgō 神功皇后, H 48.5 cm

Right Himegami 比売神 (aka Nakatsuhime 仲津姫, Ōjin’s spouse), H 55.8 cm

Designated National Treasures, PHOTOS courtesy this J-Site

HACHIMAN AS GOD OF WRITING AND CULTURE

Handbook of Japanese Mythology, by Michael Ashkenazi, Oxford University Press (March 11, 2008), page 160. "Eight banners," one of the major deities of the Shintō pantheon, Hachiman is associated with the activities of war and culture. As a buddhist deity he is worshiped as a daibosatsu (great Buddha) and protector of Buddhist temples. Goshintai in Hachiman shrines are generally either a bow or a stirrup, referring to the classical mounted archer, and more rarely a writing brush, referring to his nature as deity of culture and learning. Doves are his messengers. Appealed to during the Mongol invasions of Japan, Hachiman sent the kamikaze (divine wind) to sink the combined Mongol-Chinese-Korean fleet.

In the second century C.E. Empress Jingū, following a vision from the kami, engaged in a campaign of conquest in Korea. Pregnant by her deceased husband and fearful that childbirth would slow down the campaign, she wrapped herself with tight bandages and tied a stone weight to her belly, thus managing to carry the baby for three years in the field. Her son, the emperor Ōjin to-be, was born once the campaign was over. Jingū had dreamed that if her son was born after the campaign was won, he would be a deity, and the child was born with a mark resembling a bow guard on his forearm, thus confirming his wondrous origin. In the sixth or seventh century, the mother-and-son combination were identified together as the deity Hachiman.

Ōjin, the fifteenth emperor of Japan according to the Kōjiki, invited Korean and Chinese scholars to educate his son and courtiers in the ways of the world. As a consequence Hachiman is the patron god of writing and culture, as well as war, divination, and protection. <end quote from Ashkenazi>

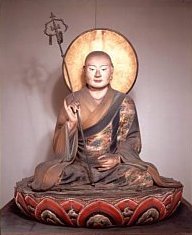

The Shinto Deity Hachiman in the Guise of a Buddhist Monk

In the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Japanese, Kamakura period, dated 1328

Japanese cypress with polychrome and inlaid crystal; joined woodblock construction

Height = 82.3 cm, Maria Antoinette Evans Fund and Contributions

Below text by Kondo Takahiro

The Shirahata sub-shrine (at Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine in Kamakura) was built by Masako Hojo in 1200. Shirahata means "White Flag" and white was the color of the Minamoto clan's banner. This sub-shrine is dedicated to the memory of Minamoto Yoritomo (founder of the Kamakura Shogunate) and Minamoto Sanetomo 源実朝 (1192–1219; second son of Minamoto Yoritomo; third shogun of the Kamakura shogunate; last heir of the Minamoto clan of Japan). When he died, so too did Minamoto's blood line. However, it does not venerate Sanetomo’s sibling Yoriie. Yoriie was Masako’s second son and the second Shogun. Historical records show that he was at odds with his mother. <end quote from Kondo Takahiro>

During the Kamakura Era, Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine was a mixture of both Shinto and Buddhism elements, highlighting the syncretic approach of Yoritomo Minamoto (1147-1199) and his claim to the lineage of the Imperial Family. In bygone days, a statue of Yoritomo was enshrined here. Hideyoshi Toyotomi (1536-1598), another warlord and ruler of Japan, visited this shrine in 1590 AD, and reportedly said: "You and I are the real heroes of Japan," stroking Yoritomo's statue on the shoulder. The statue is now kept at the Tokyo National Museum in Ueno (Tokyo).

After the Meiji Imperial Restoration of 1868, the Emperor regained imperial sovereignty (replacing the shogunate), and the new government institutionalized Shinto as the official state religion while implementing restrictive policies against Buddhism and other religions, including Christianity. Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine, during that time, was forced to remove and/or thrown away all structures and objects associated with Buddhism. For more on Shinto history, please visit the Main Shinto Page.

The crest (sasarindō 笹龍謄) of the Minamoto family is

emblazoned on the pillars of the Shirahata sub-shrine

Entrance to Shirahata Sub-Shrine at

Tsurugaoka Hachimangu in Kamakura

Statue of Yoritomo Minamoto at Genjiyama Park in Kamakura. Click image for larger photo.

Hachiman - Japanese Shinto God of War. Text courtesy japan-101.com

Hachiman was the guardian of the Minamoto clan of samurai. Minamoto no Yoshiie, upon coming of age at Iwashimuzu Shrine in Kyoto, took the name Hachiman Taro Yoshiie and through his military prowess and virtue as a leader, became regarded and respected as the ideal samurai through the ages. His descendant, Minamoto no Yoritomo, became shogun and established the Kamakura shogunate in the late 12th century. Yoritomo rebuilt Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine in Kamakura and started the reverence of Hachiman as the guardian of his clan.

Throughout the Japanese medieval period, the worship of Hachiman spread throughout Japan among not only samurai, but also the peasantry. So much so was his popularity that presently there are more shrines, numbering over 30,000, in Japan dedicated to Hachiman than any other kami. Usa Shrine in Oita prefecture is head shrine of all of these shrines and together with Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine and Iwashimuzu Shrine, are noted as the most important of all the shrines dedicated to Hachiman. <end quote>

Crest of Hachimangū Shrines

Says the Encyclopedia of Shinto (Kokugakuin Univ.): "The swirling tomoemon 巴文 served as the crest of Hachiman shrines, and it spread widely in the medieval period as the result of the frequent dedication (kanjō 勧請) of Hachiman shrines by warrior families.” <end quote>

Tomoe crests adorn the roofs at Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine (Kamakura, Japan)

Single Right Tomoe; Double Left Tomoe: Triple Right Tomoe (courtesy JAANUS)

Says JAANUS about the Tomoe: The character tomoe 巴 means eddy or whirlpool; however, it is not clear if this was the original idea of the design. Some scholars are convinced that it stems from the design on leather clothing worn by ancient archers (tomo 鞆 thus tomo-e 鞆絵), a tomo picture. Others say it was originally a representation of a coiled snake. It may be the oldest design in Japan, because it is similar in shape to the magatama 勾玉 beads of the Yayoi period. It appears as a design on the wall paintings of the Byoudouin Hououdou 平等院鳳凰堂 (1053; Kyoto) and in the Illustrated scroll of the Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari emaki 源氏物語絵巻) of the early 12c. It was widely used from the Kamakura period onward and is often found on utensils, rooftiles and family and shrine heraldry. Its frequent appearance in connection with Shinto shrines indicates that it was thought to express the spirit of the gods. Patterns of one, two and three tomoe exist, some facing left, others right. <end quote>

RESOURCES

- Shōmu Tennō and the Deity from Kyushu: Hachiman’s Initial Rise to Prominence. By scholar Bernhard Scheid, Japan Review 27 (2014): 31–51. If unavailable, see story here.

- JAANUS DATABASE (Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System)

- Metamorphosis of a Diety: The Image of Hachiman in Yumi Yawata. Story by scholar Ross Bender, appearing in the Summer 1978 edition of the Monumenta Nipponica, Volume 33, Number 2. Pages 165-178. [Includes a translation of Yumi Yawata attr. to Kanze Motokiyo Zeami.]

- Ross Bender’s 1980 dissertation for Columbia University entitled "The Political Meaning of the Hachiman Cult in Ancient and Early Medieval Japan.

- Shinzo: Hachiman Imagery and its Development by Christine Guth Kanda, Published by Harvard University Asia Center (Nov. 25 1985), Language: English. ISBN-10: 0674806506.

- Nakano Hatayoshi 中野幡能 (1916–2002). Hachiman shinkō no kenkyū 八幡信仰史の研究 (1967). Says scholar Bernhard Scheid: "Nakano-san devoted virtually his whole scholarly life to the topic of Hachiman. Hachiman shinkō no kenkyū, Nakano's opus magnus of more than 900 pages, was first published in 1967. In 1975 an enlarged edition appeared in two volumes, which added a new introduction, three chapters and an index at the end, but otherwise did not change the contents of 1967. Subsequently Nakano published studies on select topics from Hachiman shinkō as well as several large collections of source materials on Hachiman and Usa. In 2002, Hachiman shinkō jiten, a collection of essays of a more general, introductory nature was published under Nakano's editorship."

- Iinuma Kenji 飯沼賢司. Hachiman-shin to wa nani ka 八幡神とはなにか. Kadokawa Shoten, 2004.

- Hasebe Masashi 長谷部将司. "Hachiman Daibosatsu seiritsu no zentei: Kōtō no tenkan to Hachiman-shin no tensei" 八幡大菩薩成立の前提: 皇統の転換と八幡神の転成. In Nara nanto bukkyō no dentō to kakushin 奈良南都仏教の伝統と革新, ed. Samuel C. Morse and Nemoto Seiji 根元誠二. Kyōsei Shuppan, 2010, pp. 41–66.

- Encyclopedia of Shinto (Kokugakuin University, Japan)

- Empress Jingū (Jingū Kōgō) 神功皇后 (from Gabi Greve)

- Yakushiji Temple

- Tegai-e Scroll 転害会図会 (絵巻) of the Tamukeyama Hachiman Shrine. J-Site.

Also written as 転害会 (Tenkai-e) or 碾磑会.

- Viewing the Famous statue of Sogyo Hachiman at Tōdaiji (J-Site)

About the Statue | Schedule for Viewing the Statue

- Noh 能 Plays Involving Hachiman

Ominameshi 女郎花, Muromachi Era

Hōjōgawa 放生川, Hachiman River, Muromachi Era (translation by Ross Bender)

Yumi Yawata 弓八幡, The Bow of Hachiman, Muromachi Era (translation by Ross Bender)

THIS IS A SIDE PAGE

Return to Shintō Shrine Guide

Last Update June 13, 2015

Added more resources, photos, and quotes.

|

|