|

|

|

|

|

Confucius

孔子 or 孔夫子

Chinese

Kung Tzu, Kung Fu Tzu

Kung Fu Zi, Kǒng fū zǐ

Japanese

Kōshi, Koushi, Koshi

Confucian concepts still

serve as primary themes in calligraphy in both China & Japan

道 tao; path, right way

仁 ren, benevolent

徳 de, virtuous

禮 li, propriety

義 yi, morality

忠 zhong, loyalty

恕 shu, reciprocity

信 xin, trustworthy

命 ming, destiny, fate

天 tien, heaven, above

理 li, priciple

* Chinese pronunciations

|

|

Confucius and Confucianism Confucius and Confucianism

in Japanese Art and Culture

What’s Here

34 Photos, 50+ Terms

What is Confucianism?

The teachings of the Chinese sage Confucius (−552 to −479). The impact of Confucianism on the ethical and political systems of China, and later Japan, is impossible to exaggerate. Confucianism (Jp. = Jukyō 儒教) is one of three great philosophies of China. The other two are Taoism (Jp. = Dōkyō 道教) and Buddhism (Jp. = Bukkyō 仏教). Curiously all three developed at approximately the same time. Buddhism originated around −500 in India with Shakyamuni (Jp. = Shaka 釈迦), the Historical Buddha. His teachings entered China around the +1st and +2nd centuries, where they later flourished. Shakyamuni’s contemporaries in China were Confucius 孔子 (Jp. = Kōshi) and Lao-tzu 老子 (Jp. = Rōshi). Lao-tzu is the founder and "old boy" of Chinese Taoism, for legend says he was born with white hair. Most sources say he lived at the time of Confucius, but some modern scholars contest this, claiming that Taoist teachings appeared later on in the −4th century.

CHINESE CONFUCIANISM

Chn = Rújiào 儒教 Chn = Rújiā 儒家

Confucianism is not generally considered a religion or practiced like a religion, nor did it inspire great schools of art, as did Taoism and Buddhism. Rather, Confucianism developed as a set of ethical and political tools, a basket of norms that emphasized filial piety, respect for elders, social obligations, and rules of courtesy that promised humanistic, rational, and benevolent governance, harmonious family relationships, and clear-cut standards for governing the interaction among rulers, lords, vassals, and common folk, between old and young, father and son, husband and wife, etc. Over many centuries, it developed into an overarching set of moral laws, and for centuries served as the basis of China’s all-important civil examinations, which stressed the value of Confucian learning and the importance of scholarly officials (learned statesmen) who would lead by virtuous example.

- Confucianist concepts still serve as an important focus of calligraphic practice in China and Japan. Even today, numerous artists in both nations pursue calligraphy as their main profession. Their art is often focused on the key terms (see sidebar at right) appearing in the Confucian classics. Calligraphy, however, is not considered a Confucian art, but rather an art that draws its inspiration from the “individualistic” and “mystic” traditions of Taoism.

- Analects 15:23. Confucius stressed a set of rules (rituals of courtesy 禮) that all should respect. If people followed these rules, social relationships would become harmonious. But doing so also required a heightened sensitivity from the rulers and the ruled. It required benevolence (仁) and tolerance (恕), of putting oneself in the shoes of others. Confucius stated the golden rule well before the Christians: "What you do not wish upon yourself, do not impose on others" (see sidebar at right). This compares to the Christian phrase: “Do to others what you want them to do to you.” The first is inactive, the second active.

- Analects 2:3. Confucius said: “If you lead the people with administrative injunctions and put them in their place with penal law, they will avoid punishments and continue without a sense of shame. But if you lead them with excellence and show them their station through roles and rituals, they will develop a sense of shame and order themselves harmoniously.”

- The main teachings of Confucius are recorded in the Analects 論語 (Chn. = Lùnyǔ, Lunyu; Jp. = Rongo), compiled by his disciples. Confucius is also credited with authoring the Spring and Autumn Annals 春秋 (Chn. = Chun Qiu or Ch’un Ch’iu) and with editing the classic Book of Poetry 詩經 (Chn. = Shi Jing or Shih Ching). Confucianism was further developed in later centuries by other Chinese scholars, most notably Meng-tzu 孟子 (Mencius −372-289) and Hsũn-tzu 荀子 (−298-238). For a long time, six books in particular served as the basis of the so-called Confucian Classics.

|

Confucianism. Confucianism.

Is it a Religion?

When the Japanese first encountered the English word “religion” in the late 1850s, they had great difficulty translating it into Japanese, for there was no equivalent Japanese term that encompassed all the various doctrines and sects, nor a generic term as broad as “religion.” For a time, the Japanese continued to use traditional words like shū 宗 (sect, canon), kyō 教 (teachings), and ha 派 (sub-sect or faction) interchangeably for the various strands of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Christianity, and others. For a short time, “religion” was translated as “sect law” (shūhō 宗法) or “sect doctrine” (shūshi 宗旨). Ultimately, however, the Japanese settled on the term shūkyō 宗教 as the generic all-embracing translation for “religion.” Thus, in modern-day Japan, Buddhism belongs to a universal group that also includes Shintoism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. However, the Japanese government does not recognize Confucianism or Taoism as “religions.”

Zhu Xi 朱熹 (Chu Hsi)

Neo-Confucianist Scholar

National Palace Museum

Taibei, Taiwan

|

|

JAPANESE CONFUCIANISM JAPANESE CONFUCIANISM

Jp = Jukyō 儒教 Jp = Juka 儒家

In Japan, as earlier in China, Confucian ideals played a major role in the development of ethical and political philosophies. This was especially so during Japan’s formative years (+ 6th to 9th centuries), when Confucianism and Buddhism were introduced to Japan from Korea and China. Prince Shōtoku Taishi 聖徳太子 (+ 547 to 622), the first great patron of Confucianism and Buddhism in Japan, enacted a 17-Article Constitution that established Confucianist ideals and Buddhist ethics as the moral foundations of the young Japanese nation. This served for centuries as the Japanese blueprint for court etiquette and decorum.

Much later, in Japan’s Edo Period 江戸 (+1600 to 1868), also known as the Tokugawa 徳川 era, Confucian ethics experienced a revival of sorts. During the period, a revised form of Confucianism, called Neo-Confucianism (Jp. = 朱熹学 Shushigaku), gained great appeal among the warrior class and governing elite. Neo-Confucianism brought renewed attention to man and secular society, to social responsibility in secular contexts, and broke free from the moral supremacy of the powerful Buddhist monasteries.

Most modern scholars consider Neo-Confucianism to be the keynote philosophy of Tokugawa Japan, one that originated with Zhu Xi 朱熹 (+1130-1200; Chu Hsi), a Chinese scholar of China’s Southern Song period. His teachings were brought to Japan by Japanese Zen monks who had visited China in the +15th and +16th century. Zhu Xi stressed the "unity of the three creeds," the unity of the three great philosophies of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism, which had until then been considered mutually exclusive and contradictory. This three-way unity was called Sankyō 三教 in Japanese (Chn. = Sān Jiào), and literally means “Three Religions.” In Chinese and Japanese artwork, it spawned the pictorial theme known as the Three Patriarchs, along with two other related themes (see next section), each emphasizing the notion that “the three creeds are one.” In Japan, some prefer an alternative trio that includes Shintō, Confucianism, and Buddhism.

Confucius in Japanese Art

As discussed above, Neo-Confucianism emphasized the unity of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism (Jp. = Sankyō Itchi 三教一致, literally Unity of the Three Creeds). This doctrine sparked the emergence of three related themes in Chinese and Japanese painting.

- Sankyō 三教 (Three Patriarchs)

- Sansan-zu 三酸図 (Three Sages Tasting Vinegar)

- Kokei sanshō 虎渓三笑 (Three Laughers of Tiger Ravine)

These three themes became popular subjects of Chinese painting during the Southern Song and Yuan periods, and gained popularity as well in Japan during the Muromachi 室町 (+1392-1568) and Edo 江戸 periods (+1600 to 1868). In Japanese paintings, the three patriarchs -- Confucius (Confucianism), Buddha (Buddhism), and Lao-tzu (Taoism) -- are portrayed together, often in a lighthearted manner, to reflect the ecumenical Neo-Confucian doctrine.

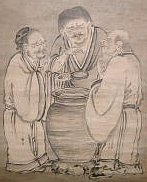

Sankyō 三教, The Three Patriarchs

Chinese = Sān Jiào. Among the best-known Japanese paintings of the trio is that by the Japanese Zen priest Josetsu 如拙 (+1386?-1428?), a treasure of Ryousokuin Temple 両足院 in Kyoto.

|

Three Patriarchs by Josetsu 如拙

Ryōsokuin Temple 両足院 in Kyoto

Muromachi Period +1392-1568

|

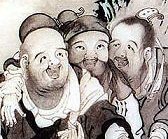

CLOSE-UP: 三教国 Three Patriarchs

Confucius (hat), Buddha (curled hair),

and Lao Tzu (white-haired elder).

By Hasegawa Tousetsu 長谷川等雪 (+1539-1610)

At Egawa Museum, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan

|

|

Three Patriarchs, Mt. Kongtong 崆峒山, China

Famous Taoist Mountain, Gānsu Province, China

Buddha (curled hair), Lao Tzu (center), Confucius

崆峒山 = Japanese = Mt. Kōtōsan or Mt. Kotosan

Photo Found Here | Details on This Mountain

|

|

|

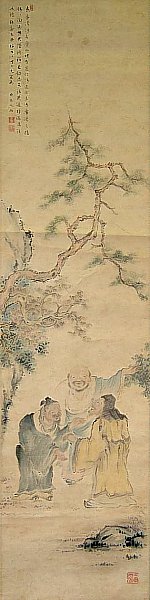

Three Sages

Tasting Vinegar

Confucius, Buddha, Lao-tsu

Muromachi Period

by Keison (啓孫)

Fukaji Temple 冨賀寺

Shizuoka Prefecture

<Photo Source>

|

|

Sansan-zu 三酸図 Sansan-zu 三酸図

Three Sages Tasting Vinegar

Below text courtesy of JAANUS. Chinese = Sansuantu. Three Chinese sages tasting wine (san 酸) from a vat. According to legend, one day the famous Chinese poet Su Dongpo 蘇東坡 (Jp. = So Touba, +1039-1112) and his friend Huang Shangu 黄山谷 (Jp. = Kou Sankoku, +1045-1105), went to a temple called Jinshansi 金山寺 (Jp. = Kinzanji) to look for the monk Foyin 仏印 (Jp. = Futsuin). Foyin, glad to see his friends, brought out a large jar of peach wine and each man eagerly tasted the brew. Simultaneously all three men raised their eyebrows and puckered their lips in surprise at the bitter taste. The three figures represent China's Three Creeds (三教 Sān Jiào), with Su Dongpo as Confucianism, Huang Shangu as Taoism, and Foyin as Buddhism. The incident serves as a parable for the ecumenical doctrine that the "Three Creeds are One" (Jp. = Sankyou Itchi 三教一致) in that the astringent taste of the wine shocks each of the three different men into recognition of the same reality. In some cases the three figures are depicted as the founders of the three main philosophies, Confucius (Confucianism), Laozi (Taoism) and Shakyamuni (Buddhism), or alternately, as the same three men who appear in the Three Laughers at Tiger Ravine (see below). Two well-known examples include one by Chinese artist Yan Hui 顔輝 (Jp. = Ganki, late +13th to early +14th century) and one by Japanese artist Kaihou Yuushou 海北友松 (+1533-1615), the latter a treasure of Myoushinji 妙心寺 Temple in Kyoto. <End JAANUS quote>

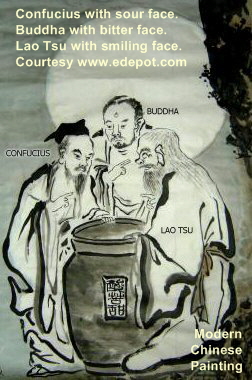

Sansan-zu 三酸図, Another Interpretation Sansan-zu 三酸図, Another Interpretation

Three Sages Tasting Vinegar (see above) is a popular theme in Chinese and Japanese art. One important variation on this theme was to show each of the three patriarchs with different facial expressions. After tasting the vat’s content, Confucius is shown with a sour face, Shakyamuni (Buddha) with a bitter expression, and Lao tsu with a smiling face. This painting theme is allegorical. Since each represents one of the three great philosophies of China, each wears an expression appropriate to that philosophy. To Confucius, the father of Confucianism, life was sour and chaotic because rules and regulations were not strictly obeyed. Indeed, the typical Chinese Confucian scholar pursued a very harsh lifestyle -- little laugher came forth from the study. This rigidity is captured nicely in an old Chinese saying about Confucius: "If the mat is not straight, the Master will not sit." To Shakyamuni, the Historical Buddha and the patriarch of Buddhism, life was bitter, filled with suffering, sickness, old age, and death. Shakyamuni believed that suffering originated from desire and attachment, and to overcome suffering one had to overcome worldly desire. Lastly we have the smiling face of Lao Tsu, the father of Taoism, whose philosophy is to “flow like water,” to live in harmony with life’s circumstances, to turn the negative into the positive, to refrain from making quick opinions about good and bad. Life is sweet, not sour or bitter, if one flows like water, without trying to dam, redirect, or interfere with the natural path of the water (stream of life).

Symbolism in This Artistic Theme

Confucius (Confucianism) = Interfering, Rules & Regulations

Shakyamuni (Buddhism) = Unappreciative, Denial, Control

Lao Tsu (Taoism) = Appreciative, Natural, Harmonious

Vat of Vinegar = Essence of Life, Nature, the TAO

Kokei Sanshō 虎渓三笑 Kokei Sanshō 虎渓三笑

Three Laughers of Tiger Ravine

Below text courtesy of JAANUS. Chinese = Huxi Sanxiao. An allegory about three Eastern literati (東晋) who realize by accident that spiritual purity cannot be measured by artificial boundaries. One day the poet Tao Yuanming 陶淵明 (Jp. = Tou Enmei, +365-417) and the Taoist Lu Xiujing 陸修静 (Jp. = Riku Shuusei, +406-477) traveled to the Donglin 東林 temple on Mt. Lu 廬山 to visit the Buddhist theologian Huiyuan 慧遠 (Jp. = E On, +334-416) who lived there as a recluse, vowing never to cross the stone bridge over the Tiger Ravine (Jp. = Kokei 虎渓) that marked the boundary of the sanctuary. After an evening together, Huiyuan accompanied his friends as they left the temple. Deeply absorbed in conversation, Huiyuan inadvertently walked with them across the Tiger Ravine bridge. When the men realized what had happened they broke out in spontaneous laughter -- hence the title of the anecdote "Kokei Sanshou" or "Three Laughers of the Tiger Ravine." It is this moment that is usually depicted in paintings. The story probably originated with the late Tang poet Guanxiu 貫休 (Jp. = Kankyuu +832-912). Variations on the theme stress that the three men represent China's three creeds -- Confucianism (Tao Yuanming), Buddhism (Huiyuan), and Taoism (Lu Xiujing) -- and that in the instant they crossed the bridge all were enlightened by realizing that narrow adherence to one philosophy or religion is contrary to true wisdom. Notable works include those by Chinese artist Ma Yuan 馬遠 (Jp. = Ba En, late +12th century), and, in Japan, by Chuuan Shinkou 仲安真康 (mid +15th century), Shoukei 祥啓 (late +15th century, Kohouan 孤逢庵, Daitokuji 大徳寺), Kanou Sanraku 狩野山楽 (+1559-1635; Myoushinji 妙心寺), and Ike no Taiga 池大雅 (+1723-76, Manpukuji 万福寺, Kyoto). <End JAANUS quote>

Symbolism in This Artistic Theme

Bridge = Buddhism, Crossing to “Other Shore”

Boundary = Taoism, Polarity, Yin/Yang, Natural Laws

Adherence to Strict / Rigid Rules = Confucianism

Confucius (Confucianism) = Tao Yuanming 陶淵明

Lao tsu (Taoism) = Lu Xiujing 陸修静

Shakyamuni (Buddhism) = Huiyuan え遠

|

虎渓三笑図

More Artwork of Three Laughers of Tiger Ravine

|

|

|

|

|

Click above image to enlarge.

Three Laughers painted

on two-panel sliding door.

by 岸連山, +1846

1800 mm X 1124 mm

Ryukoku-ji Temple 隆国寺

Temple Web Page

|

Above Photo

Three Laughers

by Syōhaku Soga

曽我蕭白 +1730-1781

Photo Source

|

|

|

|

|

Close-up of Sliding Door

|

Close-up of Sliding Door

|

|

BELOW PHOTOS OF UNKNOWN ORIGIN

FOUND ON VARIOUS WEB SITES

Three Laughers at Tiger Ravine. Close-up. See full scroll painting below.

Three Laughers at Tiger Ravine. See close-up above.

|

|

Japanese Confucianism Japanese Confucianism

in Modern Culture & Society

Confucianism failed to inspire any great schools of art in Japan, nor did it become a religion or gain a religious following. Yet it greatly influenced social behavior. Confucian concepts are still clearly evident in modern Japanese society, but most Japanese people don’t recognize them as such, as modern Japan has dressed itself predominately in Shinto and Buddhist garb. Below are a few examples of Confucian influences in modern Japan.

- Most Japanese homes still keep ancestral tablets (ihai 位牌) and altars (butsudan 仏壇) in their homes, which record the posthumous names of deceased family members and allow families to pay homage to their ancestors. Butsudan appeared in the private homes of Japan’s aristocracy at an early date, and became widespread among upper-class families during Japan’s Kamakura (+1185-1333) and Muromachi periods (+1392-1568). The placing of ancestral tablets inside the butsudan is generally considered a Confucian influence. More more details, see JAANUS.

- Modern Japan exhibits many characteristics of a well-functioning Confucian society. Singapore is another oft-quoted example of a healthy Confucian nation-state.

- Seniority system (respect for elders)

- Loyalty to company (lifetime employment system)

- Sempai / kohai system (loyalty and devotion)

- Lower rates of crime than in Western nations (trustworthy, respectful, honest). Ever lost something in Japan, or forgotten your wallet at the restaurant? In most cases, you'll be surprised that all is returned to you intact by simply returning to the restaurant or the train lost-and-found.

- Stable family structures (lower rates of divorce than in Western countries).

- Strong education system (entrance exams are very tough)

- Social ills relatively less than in Western nations (safer streets, better schools).

- The Japanese language is punctuated by numerous honorific terms and phrases of respect and consideration. People address each other based on station, with terms like sama (to show high deference), san (to display common politeness), and kun (used for children). Thus a high-ranking government official is addressed as XXXX-sama (as in "The Honorable Congress Person"), your colleague at work as XXXXX-san (as in "my esteemed colleague"), and your children or their young playmates as XXXXX-kun (as in "my darling" child). Different situations demand different levels of courtesy as well. At Japanese funerals, for example, special phrases of condolence and sympathy are used instead of normal everyday speech. When meeting people for the first time, the Japanese employ honorific language (敬語 keigo) to express respectful greetings. Decorum, deference, and courtesy are also evident in many other facets of Japanese behavior. Car drivers routinely dim their lights when idling at the traffic light. This is a courtesy to the driver in the car across the street going in the opposite direction. The Japanese people display an extreme level of self-reserve, and bad tempers are rarely displayed in public places.

- Bushido 武士道 = Code of the Warrior

The warrior code was influenced by Confucianism, Zen Buddhism and Shinto. Confucianism engendered filial piety and loyalty to one's lord. Zen helped the warrior control body / mind and overcome fears of death. Shinto brought emperor worship.

CONFUCIAN SHRINES IN JAPAN CONFUCIAN SHRINES IN JAPAN

Japan is home to many Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, but only a small number of locations are devoted to the Chinese sage Confucius. Places devoted to the scholarly Confucius are typically packed with students who pray for success in the tough school examinations, for Confucius is revered as a Patron of Learning in Japan.

Yushima Seido

Confucian Shrine

Yushima Seido 湯島聖堂

Established in 1690 by the Neo-Confucian scholar Hayashi Razan (+1583-1657) for the study of Confucianism. It was among the first institutions for higher education in Japan. The statue in the shrine compound (see photo at right) is reportedly the world’s largest standing image (4.57 meters) of Confucius, and was donated to the shrine in 1975 by the chairman of the Taiwanese Lion’s Club. The shrine is located just north of Ochanomizu Station in Tokyo.

PHOTO. A votive plaque (ema 絵馬) of Confucius at Yushima Seido in Tokyo, left behind by someone who signed the back with wishes for exam success. Photo by Yoshiaki Miura. Source: Gabi Greve PHOTO. A votive plaque (ema 絵馬) of Confucius at Yushima Seido in Tokyo, left behind by someone who signed the back with wishes for exam success. Photo by Yoshiaki Miura. Source: Gabi Greve

Yushima Shrine J-Web Site

English Access Guide | Shrine Photos

Kōshi-byō (Koshi-byo) 孔子廟 Kōshi-byō (Koshi-byo) 孔子廟

Confucian Shrine in Nagasaki

Founded in +1893. Home to the Chugoku Rekidai Hakubutsukan (Chinese History Museum), which displays objects on loan from Beijing’s Chinese National History Museum.

Shrine’s J-Site | Shrine Photos

|

|

|

|

|

Old Chinese woodblock

of Confucius

<Public Domain>

|

Confucius statue at Tokyo’s Yushima Confucius Shrine

Photo Source

|

Modern day Chinese painting of Confucius

Photo Source

|

|

In artwork, both in China and Japan, Confucius is often shown in the same standing pose, hands clasped, with scholar’s cap and long flowing robe.

|

|

OUTSIDE RESOURCES

PHOTO CREDITS & RESEARCH NOTES

-

Chinese Stamp Image at Top of Page Chinese Stamp Image at Top of Page

Stamp images of six great Chinese sages

- Black/White Drawings of Confucian Scholars from China

- Academic Resources about Confucianism.

Provides a wide collection of links to online academic resources devoted to Confucianism.

- Six Classics of Chinese Confucianism 六經

(Jp. = Rokukyō; Ch. = Liu Jing)

- Book of Poetry 詩經

- Book of History 書經

- Book of Changes 易經

- Book of Rites 禮記

- Book of Music 樂記

- Spring and Autumn Annals 春秋

- Commonly referred to as the Five Classics 五經, as the Book of Music is not extant.

- Other Outside Links

Religious Dimension of Confucianism in Japan (Peter Nosco)

Routledge Encyclopedia - Confucius & Confucianism

Routledge Encyclopedia - Neo-Confucianism

Friesian School -- Confucius & Confucianism

Japan Reference - Edo Period

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Confucius

List of Canonical Books of Confucianism

James Legge's Translation of The Analects of Confucius

The Analects in Chinese

Sacred Text Archive - Read Chinese Classics in English

Translations of key Confucian documents (David Jordon)

Translations and Books on Confucian Classics

Looking for Confucius

- Japan Times Articles on Confucius

A man in the soul of Japan, By MICHAEL HOFFMAN

Special to The Japan Times, Sunday, Sept. 10, 2006

Story One | Story Two

- Confucius Lives Next Door (Jump to Amazon). Book by author T.R. Reid, March 2000. Reid identifies the positive influence of Confucian ethics on East Asian cultures, especially in Japan. Reid spent five years in Tokyo (with his wife and two children) as the Tokyo Bureau Chief for the Washington Post, and is an NPR commentator. Reid credits Asia's success to the ethical values of Confucianism, which teaches the value of harmony and the importance of treating others decently.

- GABI GREVE PAGES

Collection of Essays about Confucius

Confucius: A Man in the Soul of Japan

East & West Echo the Sage: “Ideal Society like a Family

- Shizutani School, Okayama Pref. 閑谷学校 (しずたに)

A place for Confucian Learning in the Edo Period. Shizutani school says it was the oldest free public school in Japan. It was a Confucian school, dedicated to family, respect for elders and superiors, and discipline. It provided education to the local children. In those days, only the children of elite families had the wherewithal to receive an education. TEL: 0869-67-1436 or TEL: 0869-67-1427. <Source: Gabi Greve>

- Confucius Statue at Enchō En Park 燕趙園, Tottori, Japan. TEL.0858-32-2180. For much more on this Chinese-style garden park in Japan, please see Gabi Greve.

Confucius Statue at Enchō En Park 燕趙園

First Published May 2007

|

|