|

|

|

|

EARLY JAPANESE BUDDHISM EARLY JAPANESE BUDDHISM

Spread of Buddhism in

Asuka, Nara, and Heian Periods

Click here for condensed version of below story

INTRODUCTION. The impact of Buddhism on Japan’s political, religious, and artistic development is impossible to exaggerate. Today, some 14 centuries after Buddhism reached its shores, Japan remains one of the world’s great repositories of Buddhist practice and art, and a major wellspring for the ongoing migration of Buddhist traditions to the West.

Originating in India around -500, Buddhism swept across Asia in just 1000 years. It came last to Japan, crossing the sea in the mid 6th century, first from Korea and soon thereafter from China. Buddhism was greeted with some resistance (see below), but by +585 it was recognized by Emperor Yomei 用明 (reigned +585-587; also spelled Yōmei, Youmei), and thereafter spread fast under the patronage of his son, Shōtoku (Shotoku Taishi 聖徳太子 (+574-622). Tradition holds that Emperor Yomei once experienced a serious illness, but the young Shōtoku, impressed by the new Buddhist faith, prayed day and night by his father’s side. Emperor Yomei recovered and converted to Buddhism.

|

Regent Shōtoku Taishi

Karahon no Miei = 唐本御影

Chinese-style Portrait of a Nobleman

Nara Era Painting (8th C) in the

Imperial Household Collection

H 101.3 cm X W 52.5 cm

Oldest extant painting of

Sesshou Taishi 摂政太子

Literally “Regent Taishi”

Scepter in hand

Flanked by younger

brother (L = Eguri 殖栗) and

1st son (R = Yamashiro 山背)

|

|

When Emperor Yomei died in 587 AD, Shōtoku renounced any claim to the throne and pledged to devote his life to public duty. For the next three decades -- during the reign of his aunt Empress Suiko 推古 from +592 to 628 -- he served as prince regent and the foremost proponent of the new Buddhist teachings. Legends about Prince Shōtoku are riddled with folklore -- many miraculous tales were created in the centuries following his death. Although most contain some element of truth, others have been debunked by modern researchers and recent archaeological findings. To learn more, see the Shōtoku Taishi page. When Emperor Yomei died in 587 AD, Shōtoku renounced any claim to the throne and pledged to devote his life to public duty. For the next three decades -- during the reign of his aunt Empress Suiko 推古 from +592 to 628 -- he served as prince regent and the foremost proponent of the new Buddhist teachings. Legends about Prince Shōtoku are riddled with folklore -- many miraculous tales were created in the centuries following his death. Although most contain some element of truth, others have been debunked by modern researchers and recent archaeological findings. To learn more, see the Shōtoku Taishi page.

Shōtoku embraced the new faith and was one of its first converts. He fostered its acceptance as both a superior religious philosophy and a powerful political tool for creating strong centralized governance under the emperor’s guidance. Shōtoku is credited with constructing seven temples, including the famous Hōryūji (Houryuuji, Horyu-ji) Temple 法隆寺 in Nara and Shitennō-ji Temple 四天王寺 in Osaka, centralizing state administration, importing Chinese bureaucracy, and enacting a 17 Article Constitution that established Buddhist ethics and Confucian ideals as the moral foundations of the young Japanese nation. During his regency, Japanese missions (outside link) were dispatched to China.

The prince never became a monk (some sources say he did). In modern popular belief he is revered as a Buddhist saint, and in some traditions he is considered a manifestation of Kannon Bosatsu or Shaka Buddha. After his death, portraits of the prince began appearing in small number. See above painting, which is the oldest extant painting in Japan. Noted art scholar Ernest F. Fenollosa (+1853 - 1908) attributes this piece to the Korean Prince Asa, a contemporary of Prince Shōtoku, but modern scholars date it to the early 8th century. By the late 11th century, however, paintings and sculptures of the beloved prince occur in vast number, and many are still extant. Indeed, artwork of the prince is perhaps more abundant than artwork of all other real-life figures from Japan, with the possible exception of Koubou Daishi (Kōbō Daishi) 弘法大師 (+774 - 835), the founder of Japan’s esoteric Shingon 真言 sect of Buddhism.

|

|

Jump to Shōtoku Taishi, a special page containing more details and photos devoted to the prince.

|

|

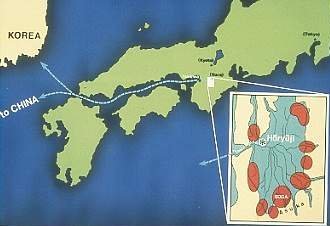

SEA PASSAGE FROM KOREA & CHINA

Below Text & Image Courtesy: Henry Smith, Columbia University

Buddhism traveled to Japan by water, on ships passing through the Inland Sea to the port of Naniwa. From here the visiting priests and artisans, together with Buddhist scriptures, images, and ceremonial implements, traveled up the Yamato River into the Yamato Basin, which you see enlarged in the map.

This moist and fertile plain, about ten miles wide and ringed by low mountains, was the home of the early Japanese state as it took shape in the fifth and sixth centuries. The red circles show the bases of the rival clans that struggled for shares of power in the emerging state. The particularly powerful Soga 蘇我 clan is seen in the Asuka region to the south. In order to break free of the pattern of endemic warfare in the Yamato Basin, Prince Shotoku took the radical step of locating his palace not in a military stronghold near the mountains but rather near the center of the basin, closer to the point where the Yamato River flows out to Naniwa 難波 (modern-day Osaka). This demonstrates the prince’s policy of relying on the power of continental ideas rather than traditional military power. <end quote from Henry Smith, who also says: “This slide show was first prepared in the late 1970s at the University of California, Santa Barbara, for use in teaching a course entitled "Japanese History Through Art and Literature."> This moist and fertile plain, about ten miles wide and ringed by low mountains, was the home of the early Japanese state as it took shape in the fifth and sixth centuries. The red circles show the bases of the rival clans that struggled for shares of power in the emerging state. The particularly powerful Soga 蘇我 clan is seen in the Asuka region to the south. In order to break free of the pattern of endemic warfare in the Yamato Basin, Prince Shotoku took the radical step of locating his palace not in a military stronghold near the mountains but rather near the center of the basin, closer to the point where the Yamato River flows out to Naniwa 難波 (modern-day Osaka). This demonstrates the prince’s policy of relying on the power of continental ideas rather than traditional military power. <end quote from Henry Smith, who also says: “This slide show was first prepared in the late 1970s at the University of California, Santa Barbara, for use in teaching a course entitled "Japanese History Through Art and Literature.">

6TH & 7TH CENTURY 6TH & 7TH CENTURY

ASUKA PERIOD (+538 - 710)

Japan first learned of Buddhism from Korea, but the subsequent development of Japanese Buddhism and Buddhist sculpture was primarily influenced by China. According to tradition, Buddhism was introduced to Japan in +552 (other sources say +538) when the king of Korea sent the Japanese Yamato 大和 court a small gilt bronze Buddha statue, some Buddhist scriptures, and a message praising Buddhism. Scholars continue to disagree on the exact date of the statue’s arrival. The Nihonshoki 日本書紀, one of Japan’s oldest extant documents, says the statue was presented sometime during the reign of Emperor Kinmei 欽明 (+539 to 571).

According to most scholars, it was the king of Kudara 百済 (aka Paekche, Paekje, Paikche, Baekje), a kingdom in Korea, who presented these gifts to the Japanese court then located in the Asuka district. Legend contents that the bronze statue was entrusted to the leader of the Soga 蘇我 clan, who acted as the chancellor of the young Japanese nation. But soon thereafter an outbreak of smallpox occurred, and clans opposed to Soga influence and Buddhism’s introduction claimed the statue was responsible for the sickness afflicting Japan.

The emperor, hoping to diffuse the situation, ordered the statue thrown into the Naniwa River, near the court’s palace in current-day Osaka City. The statue was, according to legend, thereupon pitched into the river. The discarded statue, it is said, was later fished out of the river following the victory (temporary) of the Soga clan, and is currently installed at Asuka Dera (Nara).

This legend is incorrect, for the extant statue installed at Asuka Dera (see photo here) was cast in +609. It is 2.75 meters in height, much too large to be the legendary “first” Buddha statue to arrive in Japan. According to most, the first Buddha statues to arrive in Japan are today found at Zenkoji (Zenkōji) Temple 善光寺 in Nagano Prefecture, which houses three statues known as the Amida Triad 善光寺の阿弥陀三尊.

6TH & 7TH CENTURY

NEW STATE CREED

The Korean and Chinese missionaries who thereafter came to Japan in large number brought rituals and texts from both the Theravada and Mahayana schools, but the Mahayana form in particular struck a chord with its promise of salvation to both monastic followers and laity alike. By the Nara period (see below), Buddhism becomes the state creed. The early missionaries and artisans also brought their arts and techniques for reproducing Buddhist icons and sutras. Gilt bronze statues (see Asuka Art) of the Buddhist deities appeared in great number. It is not until the late Nara and early Heian periods that wood gains supremacy. Buddhist artwork from this early period and henceforth belongs mostly to the Mahayana tradition, although artwork from Theravada and Vajrayana (Esoteric) traditions is still plentiful.

Three texts were of great influence in old Japan -- the Lotus Sutra 法華經 (Hokke kyō), the Sutra of Golden Light 金光明經 (Konkōmyō kyō), and the Benevolent Kings Sutra 仁王經 (Nin ō gyō). These were called the "Three Scriptures Protecting the State." Indeed, the Japanese court's early support for Buddhism was based largely on the court's desire to use Buddhism as an instrument of state power and consolidation rather than an instrument of salvation for the masses. Buddhist ceremonies at the time were organized predominantly for the court to ensure the welfare of the country, to expel demons of disease, and to ensure rain and thus abundant harvests.

6TH & 7TH CENTURY

RESISTANCE TO BUDDHISM

The transition to Buddhism was not always peaceful. In Prince Shotoku’s time, it had sparked a feud between pro-Shinto factions (Mononobe faction 物部) and pro-Buddhist forces (Soga clan 蘇我), one in which the young prince reportedly fought. Ironically, the pro-Buddhist Soga clan that Prince Shoutoku supported (Shoutoku was also a member of that lineage) would in the next few decades usurp the power of the throne, force Shoutoku’s heir to commit suicide (thus ending the prince’s direct line), but ultimately be destroyed themselves in a coup led by the imperial family.

Buddhism won the day, but its subsequent success owed much to its tolerance and absorption of the older deities of the indigenous Shinto mountain cults. Before Buddhism, Shinto shamanism and mountain worship were the predominant forms of native faith. Japan’s pre-Buddhist beliefs in nature spirits and holy men with magical powers were incorporated into Buddhism during the Nara and Heian periods, resulting in a complex blend of Shinto-Buddhist practice.

6TH & 7TH CENTURY 6TH & 7TH CENTURY

SHINTO IN ASUKA PERIOD

In the Asuka Period, belief in Japan's indigenous religious tradition was given the name SHINTO to differentiate it from the imported Buddhist faith. Shinto in those days was predominantly based on mountain worship, shamanistic practices, age-old rituals, and festivals that differed widely among various localities. There was no central doctrine or central organizational structure, but some indiginous religious rites were already firmly established at the court, in particular the annual Niinamesai Festival 新嘗祭 when the emperor presented the year’s first rice harvest to the local kami (deities). Emperor Tenmu 天武 (+673 - 686) found it necessary to segregate Folk Shinto from Jinja Shinto (Court Shinto) during his reign to ensure state control over the oldest traditions and festivals. Interestingly, Shinto deities were not given anthropomorphic characteristics until after the appearance of the Nihon Shoki 日本書紀 (Chronicles of Japan), one of Japan's earliest official records, disseminated around +720. Together with the Kojiki 古事記 (Record of Ancient Matters), another court-sponsored document of that time, these extensive histories were commissioned by Emperor Tenmu 天武 (+673 - 686) to demonstrate to the Chinese Emperor that the Yamato 大和 Dynasty (aka Japan) had a long and distinguished history -- thereby proving that Japan was a sovereign kingdom. These documents were not disseminated until the subsequent Nara period. For a few more details, click here.

One of the most celebrated mountain sages in the formative years was En no Gyōja 役行者. This legendary holy man was a mountain ascetic (yamabushi 山伏) of the late 7th century. Like much about Shinto-Buddhist syncretism, his legend is riddled with folklore. He was a diviner at Mt. Katsuragi on the border between Nara and Osaka. Said to possess magical powers, he was expelled in +699 to Izu Prefecture for “misleading” the people and ignoring state restrictions on preaching among commoners. He is considered the father of Shugendo (Shugendō) 修験道, a major syncretic movement that combined pre-Buddhist mountain worship (sangaku shinkou 山岳信仰) with Buddhist teachings. Popular lore says he climbed and consecrated numerous sacred mountains. Mountain ascetics today are called yamabushi 山伏 or shugenja 修験者. A major deity of the Shugendō sect is Zaō Gongen (Zao Gongen), the syncretic avatar who appeared to En no Gyōja.

|

Seated Bodhisattva

H = 16.3 cm, Gilt Bronze

Three Kingdoms Period

7th century, Korea

At Tokyo Nat’l Museum

In the Asuka and Nara periods, gilt bronze statues (kondou 金銅) were imported in great number from Korea and China, and numerous copies of these were made in Japan’s court-sponsored workshops. Bronze and clay were the most popular materials for sculpting. Wood statues were mostly imported or copied from Korean and Chinese models. It wasn’t until the late 7th century that wooden statues exceeded gilt-bronze sculptures in number and popularity. Most wooden sculptures made in Japan in this period were made of camphor (kusu 樟), carved from a single block, and then gilded or painted.

|

|

8TH CENTURY 8TH CENTURY

NARA PERIOD (+710 - 794)

The Nara period begins with the relocation of the capital to Heijoukyou 平城京 (present-day Nara). The new Japanese capital was modeled after the Chinese capital of Chang'an 長安 (Jp. = Chouan), underscoring Japan’s fascination with Tang culture, sculpture, painting, and architecture.

The Nara period might rightfully be called the Shōmu Era, for the capital in Nara during Emperor Shōmu’s reign (reigned +724 to 749) was home to between 70,000 to 200,000 people and covered roughly 4.2 kilometers from east to west and 4.7 kilometers from north to south. <source: Tanaka Hidemichi> It represented Japan's first real age of imperial splendor and urban sprawl.

Emperor Shōmu 聖武 (also spelled Shomu or Shoumu) ordered the establishment of a nationwide system of provincial temples kokubunji 国分寺. The emperor turned especially to the teachings of the Kegon School (one of the Six Schools of Nara) to serve as the basis of government. The scriptural authority of the Kegon school is the Garland Sutra (Skt. = Avatamsaka Sutra), and its main object of veneration is Birushana Buddha.

One of Emperor Shōmu’s greatest artistic achievements was to order the construction of a giant efficy of Birushana, the so-called Great Buddha (Daibutsu) at Tōdaiji Temple 東大寺 (also spelled Todaiji, Toudai-ji) in Nara, then the head of all state-established provincial temples. Legend contents that Emperor Shomu himself helped carry buckets of dirt during the construction of the giant bronze image of Birushana, which was reportedly finished in +752. At the time, it was considered the largest statue of its kind in the world. Priest Gyoki (+668-749), another luminary of the period, was instrumental in raising funds for the project. Another great achievement of Emperor Shōmu is the Shousouin 正倉院, a massive treasure-house of art collected by the emperor. The collection was donated to Tōdaiji 東大寺 in +756 by Shōmu's widow, Empress Kōmyō 光明, and is well worth a long visit by modern-day lovers of Buddhist art.

The Nara period is often portrayed as Japan’s first great age of artistic genius. This, in my mind, is not correct. The great apogee of Japanese Buddhist art occurs later, during the late Heian and early Kamakura periods. Artwork from the Nara period is mostly a reflection of Chinese influences, aristocratic tastes, and the reproduction of imported sculptural models from China and less so from Korea. Wood (although highly prized) was not yet the dominate material used to make Buddhist imagery. Wooden sculptures were, in fact, still outnumbered by statues made of metal (mostly bronze, often gilded) and clay, and competed as well against a new production technique called Kanshitsu 乾漆 (hollow dry lacquer), a method then popular in Tang China. See Making Buddha Statues for details on carving and production techniques. Clay and dry lacquer flourished in the Nara period, but were subsequently overcome by the popularity of wooden sculpture. Large bronze statues were made in great number during the Nara period, spurred on by the discovery of large quantities of copper in Japan in +708. This allowed Japan to experiment with the casting of giant bronze images, and many examples are still extant. In the prior Asuka period, metal was mostly imported.

|

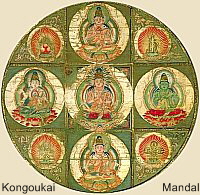

Esoteric Sects

in the Heian Era

introduce many new

deities to Japan, and

promote the merger

of Shinto-Buddhist

practices / beliefs.

Dainichi Nyorai

The central deity

of Esoteric Sects,

positioned in center

of most mandalas.

Fudo Myo-o

Angry emanation

of Dainich Nyorai

Esoteric Buddhism

includes a pantheon

of deities, who are

portrayed in great

number in the

artwork of coming

centuries.

|

|

9TH CENTURY 9TH CENTURY

HEIAN PERIOD (+794 - 1185)

During the Heian Period, the capital moved from Nara to Kyoto. This era is considered a groundbreaking period in Japanese Buddhism and Buddhist art, with two new sects introduced to the original Six Sects of Nara. These two new sects spark the flowering of Japan’s sculptural genius, and introduce mandala artwork to Japan. The newcomers were the Tendai 天台 and Shingon 真言 sects, both originating in China, brought back from China to Japan by priests Saichō 最澄 (founder of Japan’s Tendai sect) and Kūkai 空海 (founder of Japan’s Shingon sect). Both had taken the dangerous sea journey to China to learn the teachings. Upon their return to Japan, both played monumental roles in the merger of Kami-Buddhist beliefs and the emergence of Esoteric Buddhism. During the period, their efforts led to the construction of numerous Buddhist temples alongside Shinto shrines on many sacred mountains, epitomized by the powerful Tendai temple-shrine multiplex on Mt. Hiei 比叡 (Shiga Prefecture, near Kyoto), the Shingon stronghold at Mt. Koya 高野 (Kouya) and its main temple Kongoubuji 金剛峰寺 (near Kyoto), and by the holy places throughout the Kumano 熊野 mountain range.

The native Shinto kami (deities) residing on these peaks were considered manifestations of Buddhist divinities, and pilgrimages to these sites were believed to bring double favor from both their Shinto and Buddhist counterparts. Another major center of syncretism was the Kasuga 春日 shrine complex in Nara. The number of deities proliferated. Despite earlier resistance, syncretism was relatively smooth and marked by religious tolerance.

Wood began to dominate in sculpture, and was often lacquered, gilded, or painted, but sometimes left bare (especially for aromatic woods). More Japanese missions (outside link) were sent to China, but these ended around +894. By the late Heian era, Japanese Buddhist art had largely divorced itself from the influence of Tang China, and the true apogee of Japanese Buddhist sculpture is achieved late in the period and onward into the subsequent Kamakura period. Paintings, especially mandala paintings, by Japan’s Esoteric sects gained great popularity.

NOTE: Japan's break with China in the late +9th century provides an opportunity for a truly native Japanese culture to flower, and from this point forward indigenous secular art becomes increasingly important. Religious and secular art flourish in step until the 16th century, but then the importance of institutionalized Buddhism plummets owing to the Confucian ethic of the Edo-period shogunate, contact with the Western world, and political turmoil. Secular art becomes the primary vehicle for expressing Japanese aesthetics, but it is tempered greatly by the "spontaneity" of Zen Buddhism and the "affinity to nature" of Shinto. Nonetheless, generally and overall, Buddhist sculpture slips into decline after the Kamakura era.

|

最澄

Saicho (Saichō)

Founder, Japan's Tendai Sect

Posthumously called

Dengyō Daishi 傳教大師

Daishi 大師 means "Great Master"

Tendai 天台

Lit. = Heavenly Terrace School

Also called the Lotus Sutra School

空海

Kukai (Kūkai)

Founder, Japan's Shingon Sect

Posthumously called

Kobo Daishi (Kōbō Daishi) 弘法大師

Daishi means “Great Master”

Shingon 真言 (Lit. = True Word School)

Mt. Kōya 高野. Japan’s Shingon holy land is located on and around Mt. Koya. The main temple is called Kongōbuji 金剛峰寺. In 822, Kukai was awarded exclusive control over Tōji Temple 東寺 in Kyoto, making it another center of Shingon practice and worship. |

|

Monk Saichō (Tendai) & Monk Saichō (Tendai) &

Monk Kūkai (Shingon)

Priest Saichō (767 - 822) founded Japan’s Tendai sect; Priest Kūkai (774 - 835) the esoteric Shingon sect. Both schools originated in China, where Saichō (Saicho, Saichou) and Kūkai (Kukai, Kuukai) had traveled to study the teachings. Once transplanted to Japanese soil, both schools flowered with innovation. Saichō’s sect attempted a synthesis of various Buddhist doctrines, including faith in the Lotus Sutra, esoteric rituals, Amida (Pure Land) worship, and Zen concepts. Tendai gained great court favor, rising to eminence in the late-Heian era. Shingon, in contrast, was predominantly esoteric. Its doctrines were mystical and occult, and required a high level of austerity. Elaborate and secret rituals (utilizing mantras, mudras, and mandalas) were developed to help practitioners achieve enlightenment. Despite its complex practices, Shingon exerted a profound impact on religious art and the faith of the court and monastic orders.

Kūkai (aka Kōbō Daishi)

One of Japan’s Most Beloved Saints

Kūkai was the patriarch of the Shingon sect of Esoteric Buddhism. Shingon is Japan’s version of Vajrayana (Tantric) Buddhism. Together with Hinayana and Mahayana, Vajrayana represents one of the three basic forms of Buddhism in Asia today. It is especially strong in Japan and Tibet, and intricately connected with the mandala artform. Shingon’s most prominent deity is Dainichi Buddha, whose symbol is the vajra (thus Vajrayana, the Sanskrit term for Diamond Vehicle).

Posthumously named Kōbō Daishi (the Great Teacher), Kūkai remains one of Japan’s most beloved Buddhist saviors -- folklore says he attained Buddhahood before death. Portraits of him abound. The Japanese today tend to ignore doctrinal differences when honoring him. Kūkai traveled to China in 804, and was initiated in esoteric teachings by the Chinese priest Huiguo. Kūkai returned in 806, and by 816 obtained imperial sanction to construct his monastery on Mt. Kōya (Koya), a serene location on the Kii peninsula still considered a Holy Land and one of modern Japan's most popular pilgrimage sites.

He played an active role in many fields, performing rituals for the emperor, constructing a large reservoir in Shikoku for the common people, and establishing the first school for common citizens. His legend is riddled with folklore. He is credited with everything from inventing Japan’s kana script to introducing homosexuality. He is one of Japan’s most celebrated calligraphers, and supposedly published Japan’s first dictionary. He became a major patron of the arts, and reportedly founded hundreds of temples across Japan. The Shikoku Pilgrimage to 88 Sites is a popular pilgrimage attributed to Kukai. Most devotees carry a staff bearing the words "we two walk together."

10TH CENTURY 10TH CENTURY

HEIAN ERA (+794 - 1185)

Shinto-Buddhist syncretism was actually formalized and pursued based on a theory called Honji Suijaku 本地垂迹, with Shinto kami (deities) recognized as manifestations (suijaku 垂迹) of the original Buddhist divinities (honji 本地仏). In the later Kamakura Period some Shinto sects proposed the opposite, proclaiming the Shinto kami as honji and Buddhist deities as suijaku. The harmonization of Shinto (native Japanese religion), with Buddhism (from India to Japan via Korea and China) was called Shinbutsu Shugo (Shuugou) 神仏習合. According to Buddhist doctrine, a person who has done good may become a deva (celestial being) after death, encouraging humans to do good, and acting as a protector of Buddhism. When Buddhism was introduced to Japan, the Sanskrit word deva was translated in Japanese as both Ten 天 and as Kami 神 (Shinto deity), in order to facilitate the propagation of the new religion among the common people. This process of syncretization became particularly conspicuous during the Nara period. Before constructing the Big Birushana Buddha at the Todaiji Temple in Nara, Emperor Shomu (see above) first commanded Priest Gyoki to report the plan to the goddess at Ise no Jingu Shrine and to make an offering of relics of the Buddha. Buddhist scriptures were also offered to the Usa Hachiman Shrine. Syncretic practices such as building shrines on temple grounds and pagodas in shrine precincts, and of reading Buddhist scriptures before Shinto kami or presenting them to shrines, continued unabated and vigorously until Shinto and Buddhsim were forcibly separated in the early Meiji period (shinbutsu bunri 神仏分離). The theory of honji suijaku was developed by modern-day scholars to explain this relationship, which was propagated through such movements as Shingon Shinto and Tendai Shinto, with Shinto practices developing close ties with Shingon Buddhism and Tendai Buddhism during the Heian period.

Religious pilgrimages were instituted during the mid-Heian era as well, often by priests who had made pilgrimages to China, including Saichō, Kūkai, Ennin (+794 - 864) and Enchin (+814 - 891). Pilgrimages became a lasting practice thereafter. At the same time, “Lotus Sutra Meetings” (hokke-e 法華絵) became popular among the nobility. By the late 10th century, meetings were designed for the salvation of the lower classes. Shinto shrines joined in, adding to the syncretic Kami-Buddha merger of the day. Gatherings for the working class were particularly common in the Kumano 熊野 region.

Heian Buddhism and Shinto-Buddhist syncretism helped lay the foundation for the widespread propagation of Buddhism among the masses in the 13th century. See From Court to Commoner Buddhism in the Kamakura Period.

NOTE: Art historians typically divide the Heian Era into two periods, the Early Heian (+794-897) and the Late Heian (+897-1185). The latter period is typically portrayed as a period of decline in China’s artistic influence and a period of decay in the power of the Japanese imperial court. Nonetheless, extant artwork from both the early and late Heian periods suggest a consistent Japanese penchant for innovation and artistic liberty.

SHINTO TODAY. Unlike Buddhism or Christianity, Japanese Shintoism has no founder, no sutras, no body of law, no closely knit organization or priesthood (there are no nuns). There is no Shinto heaven or afterlife, no orthodox moral code -- only the social etiquette of the community and some ideas borrowed from Confucian (Chinese) philosophy. The Shinto universe is amoral and indifferent. Virtue is not always rewarded, nor is evil always punished.

Shinto priests do not follow any path toward self-realization or enlightenment. Their sacred incantations are given in an old language no longer comprehended by the laity. The Imperial Family and its earlier enforced system of emperor worship essentially denies independence to Japan's local shrines. Priests may, on occasion, serve as counselors, but their main obligations nowadays are to act as intermediary between the gods and the people (the local community), to perform shrine rituals, and to attend to the local shrine deity (kami, which can be a god or goddess or deceased person who has attained divine status). To work officially as a priest, an individual must receive an appointment from the "Association of Shinto Shrines" -- but there is no certification or qualification system. This situation does not irk the Japanese worshipper or casual shrine vistor. To them, this is the "way of the kami." Emperors and rulers may come and go, but the Japanese people and their nature will remain constant. All life forces have rough and gentle natures, all are demanding and then forgiving. The underlying nature of the people does not change, the underlying "nature of nature" does not change. For more on Japan’s Shinto traditions, please see the Shinto pages.

BOOKS & PUBLICATIONS

- Groner, Paul. "Saicho: The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School." University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2371-0. Published in year 2000 (originally published in 1984 by University of California, Berkeley). Groner-san is professor of religious studies at the University of Virginia.

- Groner, Paul. "A Medieval Japanese Reading of the Mo-ho Chih-Kuan: Placing the Kanko Ruijii in Historical Context." Japanese Journal of Religious Studies (1995) 22/1-2.

- Faith and Syncretism: Saicho and Treasures of Tendai. Published October 2005 by the Yomiuri Shimbun. A wonderful exhibition catalog commemorating the 1200th anniversary of the Tendai Buddhist Denomination. Edited by curators of the Kyoto National Museum and the Tokyo National Museum. Highly recommended, in Japanese, with English notes & captions for 236 photos in this impressive catalog (397 pages).

- Treasures of a Sacred Mountain. Kukai and Mount Koya. The 1200-Year Anniversary of Kukai’s Visit to Tang-Dynasty China, Special Exhibition Catalog of the Kyoto National Museum. Published 2005.

- Kim, Yung-Hee. Songs to Make the Dust Dance: The Ryojin Hisho of Twelfth-Century Japan. Berkeley, CA. University of California Press, 1994.

WEB LINKS

- Prince Shoutoku Taishi 聖徳太子

Shoutoku is credited with constructing numerous temples, including the famous Houryuuji (Horyu-ji) Temple 法隆寺 in Nara and Shitenno-ji Temple 四天王寺 in Osaka.

- En no Gyouja

www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/e/ennogyouja.htm

- Kingdom of Silla and the Treasures of Nara. Ancient Korea Kingdom; Buddhist Temple in Nara, Japan. By Francois-Bernard Hyghe

- Korean Influence on Japanese Culture (Marymount School, NY)

- Shinto-Buddhist Blending

www.sacredsites.com/asia/japan/

- Ancient Shinto practices can be surmised from archaeological findings from Japan’s Yayoi Period, which ended around 300 AD.

View Yayoi Pieces | Timeline of Japan’s Clay Art

- Songs to Make the Dust Dance

http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2f59n7x0/

- History of Japanese Buddhism. Wisdom Books.

buddhism.kalachakranet.org/history_japanese_buddhism.html

- Timeline - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/06/eaj/ht06eaj.htm

- Timeline: www.omplace.com/omsites/Buddhism/timeline.html

Please note that dates herein are approximations and inclusion of major developments was arbitrary, that is, by the webmaster.

- Asuka Historical Museum

www.asukanet.gr.jp/asukahome

Great photos of Japan’s earliest stone statues, pillars, temples, and artwork.Well worth a visit.

- History of Soga Clan & Early Japanese Buddhism

http://www.san.beck.org/3-11-Japanto1615.html

- EMBASSIES TO CHINA

http://darumapilgrim.blogspot.com/2005/12/kentooshi.html

http://academic.hws.edu/chinese/huang/mdln210/pilgrims.htm

- Shosoin, Imperial Repository, Nara

http://aris.ss.uci.edu/rgarfias/gagaku/shosoin.html

- TODAIJI TEMPLE

http://web-japan.org/atlas/historical/his13.html

- Kobo Daishi

http://fudosama.blogspot.com/2005/05/kobo-daishi-kukai.html

OTHER RESOURCES

- Covell, Jon Carter and Covell, Alan. Korean Impact On Japanese Culture. Korea: Hollym International Corp., 1984.

- Himiko and Japan's Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai: Archaeology, History, and Mythology, by J. Edward, Jr. Kidder (Author)

- The Lucky Seventh: Early Horyu-ji and Its Time, by J. Edward Kidder (ICU Hachiro Yuasa Memorial Museum, 1999)

- Asuka Buddhist Art: Horyu-ji by Seiichi Mizuno (Weatherhill, 1974)

|

|