Natabori Carving

by Enku (+1632 - 1695)

H = 178.5 cm

Edo Period, 1689

Ohira Kannondo, Shiga

EDO-ERA

CHRONOLOGY

Edo Period

江戸時代 +1615-1868

Tokugawa Period

徳川時代 +1615-1868

Kan'ei Bunka Era

寛永文化 +1615-1651

Kanbun Era

寛文 +1661-1673

Genroku Bunka Era

元禄文化 +1688-1715

Kyōhō Era

享保 +1716-1736

Kansei Era

寛政 + 1789-1801

Kasei Bunka Era

化政文化 +1804-1830

Bakumatsu Era

幕末 +1800-1867 |

|

HISTORICAL SETTING. The new shōgun, Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (+1542-1616), gains complete hegemony in Japan with his victory over the Toyotomi 豊臣 family in +1615, and thereafter Japan enjoys over 250 years of peace and prosperity under the leadership of 15 generations of Tokugawa shōguns 将軍 (military rulers). The military capital was established in Edo 江戸 (modern-day Tokyo), and secular arts of all kinds flourished among the growing merchant classes, military clans, and the wealthy. The importance of secular art has forever thereafter surpassed that of religious art. Buddhist sculpture continued in a downward spiral, and the influence of institutionalized Buddhism plummeted, for it could no longer compete against the Neo-Confucian policies (imported from China) favored by the Tokugawa shōguns. HISTORICAL SETTING. The new shōgun, Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (+1542-1616), gains complete hegemony in Japan with his victory over the Toyotomi 豊臣 family in +1615, and thereafter Japan enjoys over 250 years of peace and prosperity under the leadership of 15 generations of Tokugawa shōguns 将軍 (military rulers). The military capital was established in Edo 江戸 (modern-day Tokyo), and secular arts of all kinds flourished among the growing merchant classes, military clans, and the wealthy. The importance of secular art has forever thereafter surpassed that of religious art. Buddhist sculpture continued in a downward spiral, and the influence of institutionalized Buddhism plummeted, for it could no longer compete against the Neo-Confucian policies (imported from China) favored by the Tokugawa shōguns.

Indeed, most modern scholars consider Neo-Confucianism to be the keynote philosophy of Tokugawa Japan. It brought renewed attention to man and secular society, to social responsibility in secular contexts, and it broke free from the moral supremacy of the Buddhist monasteries. It also provided a powerful philosophy for exercising national rule. Society was divided into four main groups -- samurai, peasants, artisans, and merchants -- with relations among them governed by strict hierarchical rules and the Confucian virtues of filial piety and loyalty. To further ensure control, the Tokugawa shogunate enforced a seclusion policy starting in the 1630s that banned Japanese from leaving the country, and allowed only the Chinese and Dutch to conduct trade, but only from the port city of Nagasaki in Kyushu.

To stop the spread of foreign religions, the Tokugawa shōgun in +1659 ordered all Japanese families to register with Buddhist parishes, forcing everyone to declare an affiliation -- this also helped the government count the population and control tax registers. Many Japanese Christians thereafter went into “hiding.” To conceal their faith, they registered as Buddhist lay people, yet they secretly maintained their faith with clandestine codes and ingenious adaptations. For example, statues of the Virgin Mary (Mother of Jesus) were disguised as the Buddhist deity Kannon (Goddess of Mercy). These images, later called “Maria Kannon,” were made or altered to look like Kannon, but they were not worshipped as Kannon by the “secret” Christians. Many, moreover, had a Christian cross or other icon hidden inside the statue’s body.

Despite the declining fortunes of Japan’s traditional Buddhist monasteries, the Edo period gave rise to a great surge in peasant interest in Buddhist talismans, rituals, pilgrimages, and superstitions. Many of these folk beliefs came under attack in the ensuing Meiji & Modern periods. The final nail in the Buddhist coffin, so to speak, was the elevation of Shinto to state religion in the modern era.

Minor Revivals in Buddhist Statuary

In the Edo period, two wandering (itinerant) monks of great modern fame revived a carving technique known as Natabori 鉈彫 (hatchet carvings, popular from last half of the 10th century to around the 12th century). They were the Buddhist priest Enku (Enkū) 円空 +1632-1695 and the Zen priest Mokujiki Myoman (Myōman) 木食明満 +1718-1810. Nearly all of their extant pieces were carved from a single block of wood and were not hollowed out. This gives their pieces a freshness that is completely different from the refined works of traditional Buddhist sculpture. In modern Japan, their extant statues are highly prized.

Natabori 鉈彫 = Hatchet carvings, popular from last half of the 10th century to around the 12th century; revived again in Edo period. Single-block carvings (ichiboku zukuri) are sometimes called natabori, but natabori statues are differentiated from ichiboku-zukuri carvings by the characteristic round chisel (nata 鉈) markings that are added to the statue’s surface. Natabori statues are rough-cut (arabori 荒彫) or fine-cut (kozukuri 小造り), but they do not undergo final finishing (shiage 仕上げ). See Making Statues for more details on these terms. Natabori 鉈彫 = Hatchet carvings, popular from last half of the 10th century to around the 12th century; revived again in Edo period. Single-block carvings (ichiboku zukuri) are sometimes called natabori, but natabori statues are differentiated from ichiboku-zukuri carvings by the characteristic round chisel (nata 鉈) markings that are added to the statue’s surface. Natabori statues are rough-cut (arabori 荒彫) or fine-cut (kozukuri 小造り), but they do not undergo final finishing (shiage 仕上げ). See Making Statues for more details on these terms.

Some Japanese claim that natabori are incomplete works because they lack final finishing, while others claim that natabori statues are a unique sculptural style. In the Edo Period, the wandering Buddhist priests Enku (Enkū) 円空 (1632-1695) and the Zen priest Mokujiki Myoman (Myōman) 木食明満 +1718-1810 revived the technique. Nearly all of Enku’s pieces (allegedly 120,000 figures) were carved as single-block figures, including the pedestals, and were not hollowed out. Enku was not widely recognized during his lifetime, but has achieved great fame in modern-day Japan. He hailed from Mino 美濃 (modern Gifu prefecture). He was not affiliated with any temple or workshop, nor considered a professional maker of Buddhist images. Rather, he was a mountain ascetic and pilgrim who traveled about the eastern and northern parts of Japan carving statues in exchange for food and shelter.

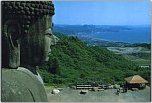

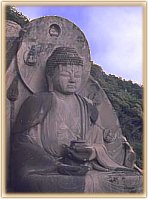

NIHON-JI DAIBUTSU NIHON-JI DAIBUTSU

Image of Yakushi Nyorai

Constructed in 1780s

The Big Buddha at Nihon-ji Temple in Chiba Prefecture is a representation of Yakushi Nyorai (the Medicine Buddha, the Buddha of Healing). This stone-cliff Buddha (magaibutsu) is 31.05 meters in height. It, plus 1,500 smaller statues in the area, were carved by master artisan Jingoro Eirei Ono and his 27 apprentices in the 1780s and 1790s. This Daibutsu of Yakushi Nyorai is twice the size of the Kamakura Daibutsu and Nara Daibutsu, making it the largest of pre-modern Japan’s extant Big Buddha statues. The Nihon-ji Temple itself dates back to 725 AD.

Above Three Photos by Photographer Goto Osami

Click any image above to see a larger photo.

At the same location, one can find carvings of 500 Rakan (Arhat) (a grouping known as the “Gohyaku Rakan” in Japan), as well as a gigantic stone carving of the Kannon Bosatsu called the “Hyaku Shaku Kannon.” The Rakan images took 20 years to carve. The project, attributed to the 15th chief priest of Nihon-ji, also occurred during the latter half of the Edo Period. All of these carvings are located at Mt. Nokogiri-yama. The literal meaning of this mountain’s name is “saw mountain,” for its shape looks like the teeth of a saw.

(L) 500 Arhats; (M) Kannon Bosatsu (R) Yakushi Nyorai

More Photos of Nihon-ji Daibutsu

-- www.town.kyonan.chiba.jp/nokogiriyama/nokogiriyama.htm

-- www.vt.sakura.ne.jp/~grgr56/goro/wtemple/wtem0p32.html

-- http://arruku.hp.infoseek.co.jp/01bousou/nokogiri.html

RESEARCH NOT YET INCORPORATED INTO SITE

Below Notes mostly from JAANUS Database http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/

- Rinpa 琳派

A school of painters and decorative artists, which began in 17c Kyoto and then spread to Kanazawa and Edo. The school began in Kyoto with Honnami Kouetsu 本阿弥光悦(1558-1637), who in 1615 founded the artistic community of craftsmen with their families supported by wealthy merchant patrons of the Nichiren 日蓮 Buddhist sect at Takagamine 鷹ケ峰 in northeastern Kyoto. There many collaborative works especially in ceramics, calligraphy and lacquerware were produced.

- Kan'ei bunka 寛永文化

Kan'ei culture. The culture of the Kan'ei era (1624-44) and by extension that of the whole early Edo period *Edo jidai 江戸時代 (1615-1868). The Kan'ei culture is characterized by two major artistic trends: aristocratic art, represented by the works of official schools of artists (*Kanouha 狩野派 and *Tosaha 土佐派), and supported by warriors and courtiers; and the art of townspeople, paticularly rich merchants in Kyoto, which is represented by the decorative art of Soutatsu 宗達 (ca 1640) and other *Rinpa 琳派 artists as well as anonymous genre paintings. This style originated in Kyoto but later moved to Edo,where bourgeios culture flourished throughout the remainder of the Edo period.

- Genroku bunka 元禄文化

Lit. Genroku culture. The middle Edo period *Edo jidai 江戸時代 chuuki 中期; (ca 1688-1715) especially the Genroku era (1688-1704). Known as a period of luxurious display, the arts were increasingly patronized by a growing and powerful merchant class. It is generally felt that the Genroku era marks the high point of Edo period culture. Two representative artists of Genroku culture are Rinpa 琳派 artist Ogata Kourin 尾形光琳 (1658-1716) and Hishikawa Moronobu 菱川師宣 (d. ca 1695), who is regarded as the founder of *ukiyo-e 浮世絵.

- Kasei bunka 化政文化

The culture of the Bunka 文化 (1804-18) and Bunsei 文政 eras (1818-30), and by extension, that of the late Edo period as a whole. It is characterized by a diversity of art trends, especially in painting. The genres that flourished during the period included: *bunjinga 文人画, *youfuuga 洋風画, *Maruyama-Shijouha 円山四条派, and *Fukko yamato-eha 復古大和絵派. Mass-production of these arts (including *ukiyo-e 浮世絵 prints), was also introduced and was supported by towns people. Some fields, particularly ceramics, achieved notable success during this time, particularly in the production of porcelain.

- Kanouha 狩野派 Painting

A hereditary school of professional artists, patronized by military governments from the late Muromachi (15c) to the early Meiji periods (19c). The Kanou school produced a large number of talented and distinguished painters, who worked in a wide variety of formats and styles on themes such as Buddhist subjects, Chinese figures, bird-and-flower paintings, animals, landscapes, genre paintings *fuuzokuga 風俗画, nanban screens nanban byoubu 南蛮屏風, and even maps of Japan and the world.

- Tosaha 土佐派

A school of painting, active from the early 15c until the late 19c, that specialized in courtly subjects painted in the yamato-e やまと絵 style.

- yamato-e やまと絵

Also written 大和絵 and 倭絵. A widely used description term which has carried various nuances in different periods, but generally applied to paintings whose subject matter, format and/or style are considered "Japanese," as opposed to something "foreign," or "Chinese."

The Rinpa school *Rinpa 琳派 traces its ancestry back to the Soutatsu 宗達 of the Momoyama period , but it flourished in the early Edo period under Ogata Kourin 尾形光琳 (1658-1716) and the patronage of the wealthy merchant class.

- Other important schools and artistic tends developed in the 18c and 19c. Westem-style painting (*youfuuga 洋風画) was popularised by Hiraga Gennai 平賀源内 (1728-79) and Shiba Koukan 司馬江漢 (1738-1818). The Maruyama Shijou school (*Maruyama Shijouha 円山四条派) was founded by Maruyama Oukyo 円山応挙 (1733-95) and noted for its development of realism.

- Japanese scholars and intellectuals, enamoured with the Chinese idea that calligraphy and painting were accomplishments suited to a literate and moral person studied Confucian texts , literature, poetry and practised calligraphy and painting. Such art was termed *nanga 南画 or *bunjinga 文人画 and was engaged in by a great many artists, including Gion Nankai 祇園南海 (1697-1751), Yanagisawa Kien 柳沢淇園 (1704-58) and Sakaki Hyakusen 彭城百川(1697 - 1758). They were followed by Ike no Taiga 池大雅 (1723-76) and Yosa Buson 与謝蕪村(1716-83). Although it was traditionally accepted that such artists in China did not paint for money, in Japan many literary artists made their living by selling their work becoming, in a sense, professional painters.

- Paintings and woodblock prints of courtesans and *kabuki 歌舞伎 actors were popular among both merchants and samurai. Called *ukiyo-e 浮世絵, such work was produced by a plethora of artists including Hishikawa Moronobu 菱川師宣 (1618-94), Torii Kiyonobu 鳥居清信 (1664?-1729), Suzuki Harunobu 鈴木春信 (1725-70) Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾北斎 (1760-1849 ) and Andou Hiroshige 安藤広重(1797 - 1858.)

- The limitation of foreign influence due to the government's seclusionist policy was compensated for by the rise of the merchant class and its energetic demand for articles of beauty. Government patronage during the period was also significant. 1867 marks the beginning of what has become modern Japan.

LEARN MORE FROM GABI GREVE

RESOURCES

JAPANESE WEB SITES JAPANESE WEB SITES

|