HISTORICAL SETTING HISTORICAL SETTING

The Kamakura period rearranged the landscape and gave birth to Buddhism for the commoner. In the political realm, decades of social unrest culminated in the victory of Minamoto Yoritomo 源頼朝 (+1147-1199) and his establishment of the Kamakura Shōgunate (Shogunate) or Bakufu 幕府 in Kamakura city, far north of Kyōto 京都. The emperor and the imperial court remained in Kyoto, symbols of culture and art, but political authority shifted to the Shōgun 将軍 (Shogun) and military class (samurai 侍) and remained there for the next seven centuries. In the religious realm, we see the spread of Buddhism among the illiterate commoner and a new spirit of realism in religious imagery. The period gave birth to new and reformed Buddhist movements -- Pure Land, Zen, and Nichiren -- devoted to the salvation of the common people. These schools stressed pure and simple faith over complicated rites and doctrines. Prior to this, Buddhism was largely the faith of the imperial court, upper classes, and monastic orders.

Simplicity and frugality became the watchwords of the new military class, replacing the perfumed embroidery of the court and the intellectual elitism of the entrenched monasteries. Religion fell naturally under the same leveling impulse, as did secular art. The new Kamakura government was anxious to rebuild and reunite, and threw its support behind the Keiha School 慶派 (based in Nara), whose heroic and powerful Buddhist statuary better suited the feudal tastes of the military overlords. Another school of sculpture, known as Zenpa 善派, appeared during the Kamakura period as well, but it was essentially an offshoot of the Kei school and today its artists are classified as part of the Kei tradition. Sculpture from this period was also influenced by the artistic styles of Song-dynasty China, especially in external features like elaborate hair topknots, long fingernails, applied jewelry, and wavy drapery. Portrait sculpture and portrait painting of prominent monks and people were also innovations of this period, with the Zen sect in particular pursuing this form of expression. Another innovation of the period was to portray various deities in the nude (e.g. Benzaiten, Jizō).

|

Sculptors of the

Kamakura Era

30+ Busshi of

the Kei School

presented below |

|

KEIHA 慶派, KEI SCHOOL, NARA BUSSHI KEIHA 慶派, KEI SCHOOL, NARA BUSSHI

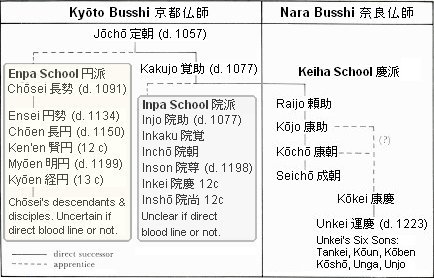

The Keiha school dominated Japanese Buddhist statuary in the 13th and 14th centuries (Kamakura Period, +1183 - 1332), and continued to influence statuary well into the Edo period 江戸 (+1615 - 1868). Called the KEI school, for most of its artists used the character KEI 慶 in their names. The term HA 派 literally means school or group. Like the powerful Enpa 円派 and Inpa 院派 schools based in Kyoto, the Kei school traced its lineage (see below chart) back to the famous Heian-era sculptor Jocho (Jōchō) 定朝. The Kei school is also known as the Nara Busshi 奈良仏師 or Nantō Busshi 南東仏師 (see Glossary for details) because their main workshop was located at Kofukuji (Kōfukuji) Temple 興福寺 in Nara. Nonetheless, they also ran workshops in Kyoto (Kyōto 京都) and the outlying provinces (see Kei Workshops). There are several reasons for the Keiha’s rise to prominence in the Kamakura period.

- Kei artists did not enjoy strong connections with the Kyoto imperial court, who instead supported the Enpa and Inpa schools based in Kyoto. The Kyoto schools carved pieces of great delicacy, refinement, and elegance, which were favored by the Kyoto court and aristocracy. The Kei school’s lack of close imperial ties appealed to the new military government in Kamakura, which scorned aristocratic tastes and was anxious to eliminate court influence and court meddling in state affairs.

- The Keiha’s sculpture embodied a new sense of power, dynamism, and realism, one that contrasted with the refined sculptural styles of the Enpa 円派 and Inpa 院派 schools from Kyoto. This too appealed to the new military government in Kamakura, as did the Keiha’s strong understanding and reinterpretation of the classical styles of the earlier Nara and Heian periods. The work of Nara’s Kei artists was often labeled as “crude” by their rivals in Kyoto, highlighting the difference in their styles.

Major temples had been damaged during the conflict between the Minamoto (Genji 源氏) and Taira (Heike 平家) clans during the Genpei War 源平合戦 (Genpei Kassen + 1180 to 1185). Once the conflict ended (victory going to Minamoto), one of the top priorities was to rebuild and repair Japan’s important religious structures. The most prestigious reconstruction projects were undertaken at Kofukuji (Kōfukuji) Temple 興福寺 and Todaiji (Tōdaiji) Temple 東大寺, both in Nara and both burnt to the ground by Taira Shigehira 平重衡 in +1180. Not surprisingly, the Kamakura Shogunate (Shōgunate, Bakufu 幕府) awarded these commissions to the Kei school, the so-called Nara Busshi based in Nara. The success of the Keiha school in remaking the statuary of these two important temples spearheaded its rise as the dominant force in Japanese Buddhist statuary, with both the Enpa 円派 and Inpa 院派 schools suffering significant declines in importance thereafter (essentially, the Kyoto schools were forced to incorporate the popular Kei style in their statuary, and thus in the subsequent period were enveloped by the Kei school). Kei artists also set up workshops in outlying provinces and played a major role in creating statuary for the new military capital in Kamakura. The most acclaimed Kei artist was Unkei 運慶 (d. 1223). Another acclaimed Kei sculptor was Kaikei 快慶, who also sprang from the workshop of Kokei (Kōkei) 康慶, who was Unkei’s father. But Kaikei was not related by blood -- he was a brilliant apprentice to Unkei’s father. All three worked together on various projects, with Unkei and Kaikei commonly considered the best Kei sculptors of the age. Major temples had been damaged during the conflict between the Minamoto (Genji 源氏) and Taira (Heike 平家) clans during the Genpei War 源平合戦 (Genpei Kassen + 1180 to 1185). Once the conflict ended (victory going to Minamoto), one of the top priorities was to rebuild and repair Japan’s important religious structures. The most prestigious reconstruction projects were undertaken at Kofukuji (Kōfukuji) Temple 興福寺 and Todaiji (Tōdaiji) Temple 東大寺, both in Nara and both burnt to the ground by Taira Shigehira 平重衡 in +1180. Not surprisingly, the Kamakura Shogunate (Shōgunate, Bakufu 幕府) awarded these commissions to the Kei school, the so-called Nara Busshi based in Nara. The success of the Keiha school in remaking the statuary of these two important temples spearheaded its rise as the dominant force in Japanese Buddhist statuary, with both the Enpa 円派 and Inpa 院派 schools suffering significant declines in importance thereafter (essentially, the Kyoto schools were forced to incorporate the popular Kei style in their statuary, and thus in the subsequent period were enveloped by the Kei school). Kei artists also set up workshops in outlying provinces and played a major role in creating statuary for the new military capital in Kamakura. The most acclaimed Kei artist was Unkei 運慶 (d. 1223). Another acclaimed Kei sculptor was Kaikei 快慶, who also sprang from the workshop of Kokei (Kōkei) 康慶, who was Unkei’s father. But Kaikei was not related by blood -- he was a brilliant apprentice to Unkei’s father. All three worked together on various projects, with Unkei and Kaikei commonly considered the best Kei sculptors of the age.

Major KEIHA Workshops. Their primary workshops were at Shichijō Bussho in Kyoto, as well as at their headquarters in Nara’s Kōfukuji (Kofukuji) Temple 興福寺. They also set up workshops in the outlying provinces. The Keiha flourished in the 13th and 14th centuries owing to the strong patronage of the military government in Kamakura. Over time, the Shichijō Bussho expanded to three main workshops:

- Shichijō Naka Bussho 七条中仏所; established in the 13th century by Kōben 康弁, Unkei's third son.

- Shichijō Higashi Bussho 七条東仏所; established in the 14th century by Kōshun 康俊, son of Unjo 運助, grandson of Unkei.

- Shichijō Nishi Bussho 七条西仏所; established by Unkei’s fifth-generation descendant Kōyo 康誉 in the 14th century.

- In the late 14th century, the sculptor Kankei 覚慶 split from the Keiha to form an independent guild called Tsubai Bussho 椿井仏所.

- The term Shichijō Bussho 七条仏所 is occasionally used as a general term to refer to the Keiha school. The headquarters of the Kei school was at Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 in Nara. It was founded by Raijo in the early 11th century. But before then, the main workshop was located in Kyoto's Shichijō Takakura 七条高倉 area, founded by Jōchō’s 定朝 son Kakujo 覚助 (d. +1077).

KEIHA SCHOOL (NARA BUSSHI)

From Jōchō to Unkei’s Sons

|

Note: The above chart is based in part on one appearing in Mori Hisashi’s book Sculpture of the Kamakura Period (ISBN 0-8348-1017-4). The KEIHA school rose to prominence under Unkei. As for Unkei’s father, KOKEI, little is known of his lineage. Some think he was an apprentice to either Kōjo or Kōchō.

|

|

Keiha School Busshi. Also see lineage chart above and below.

- Jōchō 定朝 (d. +1057). Patriarch of Japan’s three most acclaimed schools of Buddhist statuary -- the Enpa and Inpa schools of Kyoto and the Keiha school of Nara. Visit the Jōchō Page and the Heian-Era Busshi Page for more details and photos.

- Kakujo 覚助 (d. +1077). Son and successor of Jōchō. Kakujo established his Shichijō Bussho 七条仏所 workshop in Kyoto's Shichijō Takakura 七条高倉 area. The workshop remained active from the late 12th century into the 19th century, and served as an important workshop for Kei artists. Unkei, the undisputed champion of Kamakura sculpture, moved to Kyoto in the latter half of his life, establishing a workshop in the same area. No extant artwork by Kakujo.

- Raijo 頼助. Son and successor of Kakujo. Raijo was not content in Kyoto, for two other powerful Busshi groups (the Enpa 円派 and Inpa 院派) had a near-monopoly on statue production and court patronage. These schools all sprang from the workshop of the acclaimed Jōchō, who was Kakujo’s father and Raijo’s grandfather. Raijo established his workshop at Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 in Nara, which over time became the main headquarters of the Keiha School 慶派. Raijo’s decision to move to Nara was a wise one, for he and his lineage quickly gained the support of the influential Fujiwara 藤原 clan located in Nara. Kōfukuji (Kofukuji) Temple, moreover, was the clan temple of the powerful Fujiwara family. During his lifetime, Raijo was awarded Hokkyō (Hokkyo) rank, the third highest title among Buddhist sculptors. No extant artwork by Raijo.

- Kōjo 康助 (Kojo). Son of Raijo. Based in Nara. The lack of large-scale projects in Nara during his lifetime required him to accept assignments in Kyoto. No extant artwork.

- Kōchō 康朝 (Kocho). Son of Kōjo. Based in Nara. The lack of large-scale projects in Nara during his lifetime required him to undertake assignments in Kyoto. No extant artwork.

- Seichō 成朝 (Seicho). Son of Kōchō. Sired no son to succeed him, and is therefore assumed to have died rather young. In +1181, Seichō presented the imperial court in Kyoto with a genealogy list of the Nara Busshi, listing six generations -- Jōchō, Kakujo, Raijo, Kōjo, Kōchō, and Seichō. The list was part of Seichō’s attempt to convince the court that the Nara Busshi had first rights to remake the statues of Kōfukuji (Kofukuji) Temple 興福寺 and Tōdaiji (Todaiji) Temple 東大寺, both in Nara, both burnt to the ground in +1180 during the Genpei War 源平合戦 (Genpei Kassen). Around +1185, Minamoto Yoritomo 源頼朝 (+1147-1199), the leader of the military government in Kamakura, invited Seichō to Kamakura to make statuary for Shōchōju-in (Shochoju-in) Temple 勝長寿院. The temple no longer exists, but Seichō’s journey to Kamakura no doubt helped pave the way for other Nara Busshi to move to Kamakura and other outlying areas. It is thought that Unkei, the most brilliant sculptor of the Kamakura period, may have accompanied Seichō on his journey to Kamakura, but this remains unclear. No extant artwork by Seichō.

Keiha 慶派 (Kei School) in Kamakura Era

Starting with Kōkei, Unkei’s Father

Data from Sculpture of the Kamakura Period (ISBN 0-8348-1017-4)

Also from 日本史小百科 ・彫刻 ・久野健編 ・近藤出版社刊

|

不空羂索観音

Fukūkenjaku Kannon

by Kōkei, dated +1189.

Lacquer & gold Leaf

over wood, H = 348 cm

Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺, Nara

Photo: Heibonsha Survey, V11

|

|

Kōkei 康慶 (Kokei) Kōkei 康慶 (Kokei)

Father of acclaimed sculptor Unkei. Kōkei was the leader of the Nara Busshi (aka Keiha school) when large-scale restoration work was underway in Nara at Tōdaiji (Todaiji) Temple 東大寺 and at Kōfukuji (Kofukuji) Temple 興福寺. Both temples had been burnt to the ground in +1180 by the Taira 平 clan. Both were among the Seven Great Nara-Era Temples. But Seichō, the true head of the Nara Busshi, was away working on a project for the Shōgun Minamoto in Kamakura when restoration efforts began at Tōdaiji. During his absence, Kōkei acted as Seichō’s substitute chief in Nara. Kōkei eventually succeeded Seichō as head of the Nara Busshi, but Kōkei, according to most scholars, shared no blood ties with Seichō. Some suggest Kōkei was Kōchō’s younger brother, while others think he was an apprentice of either Kōchō or Kōjo. The latter two busshi are one generation older than Kōkei. But evidence is lacking and Kōkei’s genealogy remains a mystery. With the death of Seichō, leadership of the Kei School passed to Kōkei and then to his son Unkei. Near the end of his life (sometime around +1196), Kōkei transferred his title of Hōgen (Hogen 法眼, lit. eye of the law) to Unkei, his son and successor. Hōgen was the second highest Buddhist rank awarded to artists in those days. One of the final records about Kōkei comes from Tōdaiji Temple, which commissioned Kōkei to carve Gigaku 伎楽 masks for theatrical and ceremonial dances that had been performed at Buddhist temples in Japan since the 6th century. Gigaku, however, died out as an art form during the Kamakura era. <Editor’s Note. Unsure if these masks are extant> See photos above and below for extant work by Kōkei.

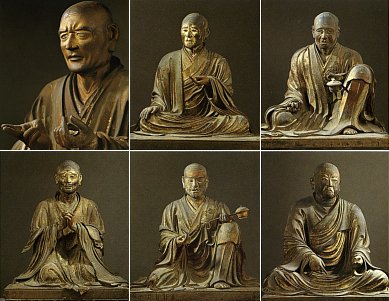

Six Patriarchs of Japan’s Hossō School. Carved by Kōkei, father of Unkei.

Colored Wood, Dated +1189, H = 73.3 cm to 84.4 cm

National Treasures at Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 in Nara. Photo courtesy of temple catalog.

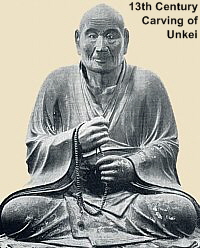

Unkei 運慶 (d. 1223). It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of Unkei to the world of Japanese Buddhist statuary. He is the undisputed champion of Kamakura-era statuary, which featured a new realism, heroic spirit, power and passion, muscular bodies, plump fleshy faces, and virile strength. His life has been well documented. Although many of his works are still extant, most have been lost. He grew up during a very turbulent time in Japanese history (see above Overview of Kamakura Period), and lived and worked in the three most important cities of his age -- Nara, Kyoto, and Kamakura. His efforts to remake and restore the great temple treasures of Nara and Kyoto, plus his early exposure to the raw emotions of the Kamakura region and the new military class (which scorned the aristocratic tastes and indulgences of the Kyoto imperial court and nobility) greatly influenced his artwork. He became the most influential artist of his time, and today is perhaps the most widely known artist of Buddhist sculpture in Japan. For more details and photos, see the Unkei page. Also see the lineage chart above. Unkei 運慶 (d. 1223). It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of Unkei to the world of Japanese Buddhist statuary. He is the undisputed champion of Kamakura-era statuary, which featured a new realism, heroic spirit, power and passion, muscular bodies, plump fleshy faces, and virile strength. His life has been well documented. Although many of his works are still extant, most have been lost. He grew up during a very turbulent time in Japanese history (see above Overview of Kamakura Period), and lived and worked in the three most important cities of his age -- Nara, Kyoto, and Kamakura. His efforts to remake and restore the great temple treasures of Nara and Kyoto, plus his early exposure to the raw emotions of the Kamakura region and the new military class (which scorned the aristocratic tastes and indulgences of the Kyoto imperial court and nobility) greatly influenced his artwork. He became the most influential artist of his time, and today is perhaps the most widely known artist of Buddhist sculpture in Japan. For more details and photos, see the Unkei page. Also see the lineage chart above.

UNKEI, SPECIAL PAGE

FEATURING 24 PHOTOS

Jōkaku 定覚 (Jokaku). Son of Kōkei 康慶 and Unkei's younger brother. Active in late 12th century, early 13th century. Worked on the restoration at Tōdaiji Temple 東大寺 around +1996; worked with Kaikei 快慶 on a Nyoirin Kannon 如意輪観音 statue and responsible for carving a large statue of Tamonten 多聞天. His name appears in period records for other projects in Nara and Kyoto. Unfortunately none of those statues has survived. His career as an active Busshi (+1194-1203) was relatively short. No extant statuary to my knowledge. He had a son named Kakuen 覚円 who became a monk of the Tendai 天台 sect.

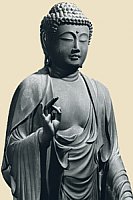

Kaikei 快慶 (died approx. +1223). Another acclaimed Kei sculptor from the Kamakura period, perhaps just as famous as Unkei in those days. The two were contemporaries. Both sprang from the workshop of Kōkei 康慶, the biological father of Unkei. Kaikei was one of Kōkei’s most brilliant apprentices, but he was not related by blood. Kaikei and Unkei worked together on various projects, and the two are commonly considered the best Kei sculptors of the age. A friendly rivalry existed between the two, with Kaikei actually assigned greater responsibilities than Unkei until at least the early 13th century. Kaikei was awarded Hokkyō rank in +1203, and Hōgen 法眼 rank in +1208, some of the highest titles bestowed on artists in those times. Art scholars typically divide his extant work into three periods: (1) his early years, when his statuary reflected the vivid realism of the Kei school; (2) his middle period, from around +1200 to +1208, a period when he developed his own unique statuary style called Annami and gained the Hokkyō rank; and (3) his late period, his Hōgen (Hōgen) 法眼 period, from +1208 until his death around +1223 / 26, when he made many small images of Amida Buddha. His Annami style was copied, formalized, and stereotyped in coming centuries, never again to reach its earlier brilliance. For more details and photos, see the Kaikei page. Also see above lineage chart. Kaikei 快慶 (died approx. +1223). Another acclaimed Kei sculptor from the Kamakura period, perhaps just as famous as Unkei in those days. The two were contemporaries. Both sprang from the workshop of Kōkei 康慶, the biological father of Unkei. Kaikei was one of Kōkei’s most brilliant apprentices, but he was not related by blood. Kaikei and Unkei worked together on various projects, and the two are commonly considered the best Kei sculptors of the age. A friendly rivalry existed between the two, with Kaikei actually assigned greater responsibilities than Unkei until at least the early 13th century. Kaikei was awarded Hokkyō rank in +1203, and Hōgen 法眼 rank in +1208, some of the highest titles bestowed on artists in those times. Art scholars typically divide his extant work into three periods: (1) his early years, when his statuary reflected the vivid realism of the Kei school; (2) his middle period, from around +1200 to +1208, a period when he developed his own unique statuary style called Annami and gained the Hokkyō rank; and (3) his late period, his Hōgen (Hōgen) 法眼 period, from +1208 until his death around +1223 / 26, when he made many small images of Amida Buddha. His Annami style was copied, formalized, and stereotyped in coming centuries, never again to reach its earlier brilliance. For more details and photos, see the Kaikei page. Also see above lineage chart.

KAIKEI, SPECIAL PAGE

FEATURING 20+ PHOTOS

Kaikei’s Students. Three other important Kei artists sprang from Kaikei’s workshop, and carried on his Annami-style sculpture. Also see lineage chart above.

- Gyōkai 行快 (Gyokai). Active in first-half of the 13th century. Senior apprentice of Kaikei. Awarded Hōgen rank. Two extant works: (1) Shaka Nyorai 釈迦如来 at Daihō-on-ji Senbon Shakadō 大報恩寺・千本釈迦堂 and (2) one smaller statue of the Senju (1000-Armed ) Kannon 千手観音 at Sanjūsangendō. However, the Shaka statue is probably a reproduction, as the original was reportedly damaged or destroyed in earlier centuries.

- Eikai 栄快. Apprentice to Kaikei. Active in mid-13th century.

- Chōkai 長快 (Chokai). Apprentice to Kaikei. Active in mid-13th century.

|

|

|

|

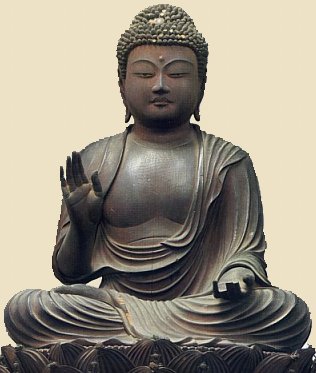

Shaka Nyorai 釈迦如来

Work by Gyōkai 行快. Lacquer & gold leaf

over wood. H = 91 cm. 13th Century.

Daihō-onji Temple 大報恩寺 Kyoto

|

Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師

Work by Chōkai 長快. Painted Wood

H = 69.4 cm, 13th Century

Roku Haramitsuji Temple 六波羅蜜寺 in Kyoto

|

|

|

|

UNKEI’S SIX SONS: All six pursued careers as Busshi (Buddhist sculptors). Work by Tankei, Kōben, and Kōshō is still extant. Unkei had many other apprentices besides his sons, plus other important artists who are categorized as Keiha artists. They are presented below as well. For lineage, please see the above lineage chart.

- Tankei 湛慶 -- 1st son, details below)

- Kōun (Koun) 康運 -- 2nd son, details below)

- Kōben (Koben) 康弁 -- 3rd son, details below)

- Kōshō (Kosho) 康勝 -- 4th son, details below)

- Unga 運賀 -- 5th son, details below)

- Unjo 運助 -- 6th son, details below)

- Unkei’s Other Descendants (details below)

- Keishun (apprentice; details below)

- Jōkei (Jokei) #1 定慶 (Kei school; details below)

- Jōkei (Jokei) #2 定慶 (Kei school; details below)

- Kōyū (Koyu) 幸有 (details below)

- Zen'en 善円, Zenkei 善慶, Zenshun 善春 (details below)

TANKEI 湛慶 (+1173-1256). Unkei’s eldest son and main apprentice. An acclaimed sculptor of the dominant Keiha school during the Kamakura period, whose workshop was located in the Shichijō District 七条仏所 of Kyoto. During his long career (he died when 83), he was honored with the top three ranks available to Buddhist sculptors (Hō-in 法印, Hōgen 法眼, and Hokkyō 法橋). He helped to restore the statuary at Tōdaiji Temple 東大寺 and Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺, but is perhaps best remembered for the major role he played in remaking the statuary for Rengeōin (Renge-o-in) Temple 蓮華王院, a Tendai-sect temple in Kyoto, which was destroyed in a fire in +1249. More commonly known as Sanjūsangendō (Sanjusangendo) 三十三間堂, this temple contains 1,001 figures of the Senju (1,000-Armed) Kannon 千手観音. The central figure of the seated Senju Kannon was carved by Tankei (see below photos), as well as nine other smaller extant versions of the deity. Tankei was 81 years old when the central Kannon statue was completed in +1254, and was assisted by two nephews -- Kōen 康円 (son of Kōun) and Kōsei 康清 (son of Kōshō). Other extant work by Tankei includes statues of Bishamonten 毘沙門天 flanked by two attendants (Kyōji 脇侍) at Sekkeiji Temple 雪蹊寺 in Kochi Prefecture, and statues of Zemmyōshin 善妙女神 and Byakkōshin 白光神 attributed to Tankei at Kōzanji Temple 高山寺 northwest of Kyoto. Tankei’s statuary is noted for its understated, gentle, and refined realism, a suppression of busy details, and plump faces.

Seated Senju (1000-Armed) Kannon 千手観音座像 (in center)

12th Century, Photo from Sanjūsangendō 三十三間堂 Brochure

Carved by Tankei (Unkei’s son)

(L) Senju (1000-Armed) Kannon 千手観音 by Tankei

12th Century, Photos Courtesy Sanjūsangendō Brochure

Smaller Senju (1000-Armed) Kannon by Tankei, 12th Century

Sanjūsangendō in Kyoto, dated +1254, wood with gold leaf.

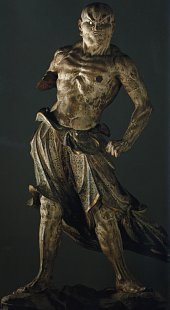

Niō 仁王 Guardians, attributed to Tankei or to his supervision.

At Sanjūsangendō in Kyoto, approx. 165 cm in height. Poly-chromed Wood, Joined Block Construction

Stunning masterworks of realism, these two statues are part of a set called the 28 Attendants

(Nijūhachi Bushū 二十八部衆) to Senju Kannon. The set at Sanjūsangendō actually contains

30 statues, of uneven quality, not firmly dated nor attributed. Some scholars believe the best pieces,

including the two Niō, were made by Tankei or made under Tankei’s supervision.

Kōun 康運 (Koun). Unkei’s second son, active sculptor between +1198-1223. No known extant artwork. However, Kōun’s son Kōen 康円 was one of the most active sculptors of the Keiha school in the Kamakura period, ultimately becoming the successor of his uncle Tankei. See Kōen below. Also, some suggest that Kōun worked under an assumed name (pseudonym), and that the acclaimed Kamakura-era sculptor Jōkei I is in fact none other than Kōun. This has never been proven <source Mori Hisashi, p.91>

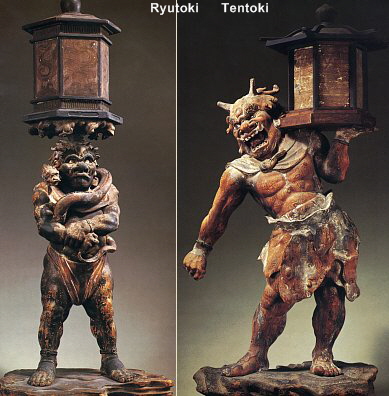

Kōben 康弁 (Koben). Unkei’s third son. Active between +1198-1215. Established his own worship -- Shichijō Naka Bussho 七条中仏所 -- in Kyoto’s Shichijō district in the early 13th century. Two of his statues are extant. They are the Ryūtōki Ryūzō (Ryutoki Ryuzo) 竜燈鬼立像, a pair of demons-goblins dated to +1215 and located at Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 in Nara. One is called Tentōki (Tentoki ) 天燈鬼 and the other Ryūtōki (Ryutoki) 龍燈鬼. <Some scholars, however, believe the Tentōki goblin was made by a different busshi. Source: Mori> Also see Four Heavenly Kings, who are nearly always depicted standing atop similar demons called the Jyaki.

Ryūtōki Ryūzō 竜燈鬼立像

Two Jyaki 邪鬼 (goblins) carrying lanterns to light up the road in front of Shaka Nyorai.

Dated +1215, by Kōben, Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺, Nara. Painted wood. Japanese Cypress.

L: Ryutoki (Ryūtōki 龍燈鬼), H = 77.8 cm R: Tentoki (Tentōki 天燈鬼), H = 78.2 cm

Inset Crystal Eyes (Gyokugan 玉眼), Joined-Block Technique (寄木造)See Offerings of Light for details on lanterns.

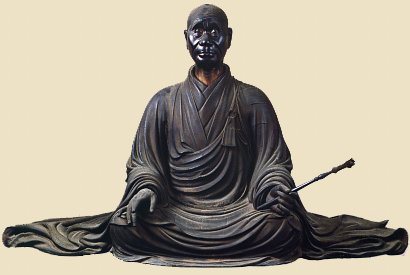

Kōshō 康勝 (Kosho). Unkei’s fourth son. Active between +1198-1233. Kōshō’s son Kōsei was also an active sculptor. Around +1198, Kōshō worked together with his father Unkei and his two brothers Tankei and Kōben on restoring the Niō-Niten 仁王・二天 statues at Tōji Temple 東寺 in Kyoto, and in +1208 he worked on the restoration of the Kōmokuten 広目天 statue at Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 in Nara. Extant statues by Kōshō include:

- Seated Amida Buddha 阿弥陀如来 at Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺 in Nara. Dated +1232. H = 64.6 cm. Bronze.

- Portrait statue of Kūkai 空海 (Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師) at Tōji Temple 東寺 in Kyoto. 13th Century. Wood.

-

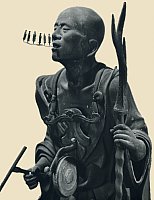

|

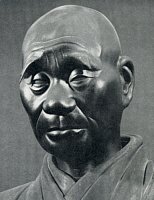

Monk Kuya 空也, H = 117.5 cm

Painted wood. By Kōsho.

13th century, at Roku

Haramitsuji 六波羅密寺, Kyoto

|

|

Portrait statue of Kūya 空也 (Kuya) at Roku Haramitsuji 六波羅密寺 in Kyoto. The temple is also known as Saikōji 西光寺. Kūya (+903-972) or Kūya Shūnin 空也上人 was a famous 10th-century Japanese monk who gained the monikers “Sage of the People” (Ichi no Hijiri 市聖) and "Sage of Amida" (Amida Hijiri 阿弥陀聖), for he walked among the common folk preaching simple faith in Amida Buddha while praying constantly to Amida for their salvation. During his many years of traveling around the countryside, he practiced a form of chanting that employed song and dance (odorinenbutsu 踊念仏). In this realistic portrait sculpture, there are six miniature Amida images flowing out of his mouth -- they represent his prayers, specifically the chanting of the six-character devotional nenbutsu 念仏 to Amida (Namu Amidabutsu 南無阿弥陀仏). Simple facial features, dressed in peasant’s garb with wrinkled clothing, wearing straw sandals, holding a stick to beat his gong for the odorinenbutsu, with bodily veins even visable. The six characters of Amida’s nenbutsu symbolize the six states of karmic rebirth. Portrait statue of Kūya 空也 (Kuya) at Roku Haramitsuji 六波羅密寺 in Kyoto. The temple is also known as Saikōji 西光寺. Kūya (+903-972) or Kūya Shūnin 空也上人 was a famous 10th-century Japanese monk who gained the monikers “Sage of the People” (Ichi no Hijiri 市聖) and "Sage of Amida" (Amida Hijiri 阿弥陀聖), for he walked among the common folk preaching simple faith in Amida Buddha while praying constantly to Amida for their salvation. During his many years of traveling around the countryside, he practiced a form of chanting that employed song and dance (odorinenbutsu 踊念仏). In this realistic portrait sculpture, there are six miniature Amida images flowing out of his mouth -- they represent his prayers, specifically the chanting of the six-character devotional nenbutsu 念仏 to Amida (Namu Amidabutsu 南無阿弥陀仏). Simple facial features, dressed in peasant’s garb with wrinkled clothing, wearing straw sandals, holding a stick to beat his gong for the odorinenbutsu, with bodily veins even visable. The six characters of Amida’s nenbutsu symbolize the six states of karmic rebirth.

- Kōshō is also attributed with making the four wooden statues of the Shitennō 四天王 at Enjōji (Enjoji) Temple 円成寺 in Nara Prefecture.

Unga 運賀 Unga 運賀

Unkei’s fifth son. Active between +1198-1255. During his lifetime he gained the rank of Hokkyō, the third highest title awarded to sculptors. Although no work by Unga has survived, one can still assume his work closely followed the realistic style of his acclaimed father, Unkei.

In fact, the statue of Seshin Bosatsu 世親菩薩 at Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 in Nara, made under the supervision of Unkei or sometimes attributed to Unkei, was actually carved by Unga (according to temple inscriptions). Nine statues in total were carved for the temple between +1208-1212, with Unkei directing 10 busshi and numerous other minor busshi. Only three of the nine statues are extant, and each was apparently carved by a different busshi. But Unkei did not allow the personalities of the sculptors to surface in the statues, and the style that predominates in all three is vintage Unkei, and thus the statues are attributed to Unkei and his supervision.

Unjo 運助. Unkei’s sixth son. Active in first half of 13th century. No extant work by Unjo. His son Kōshun 康俊 established a workshop in Kyoto in the 14th century, from which Kōshun and his son Kōsei 康成 flourished.

UNKEI’S GRANDSON

Kōen 康円 (Koen). Koen (+1207-1284). Grandson of Unkei 運慶. Son of Kōun 康運. Successor to Tankei 湛慶 (Kōun’s brother). Kōen was a renowned sculptor of the Keiha school during the late Kamakura period. Many of his pieces are still extant. He was awarded Hōgen 法眼 rank in his career.

- Appentice to his uncle Tankei 湛慶 during the restoration of the statuary at Sanjūsangendō (Rengeōin Temple 蓮華王院) in Kyoto between +1251-1254. Following Tankei’s death in +1256, Kōen became a master busshi. Six of the smaller Senju (1000-Armed) Kannon statues at Sanjūsangendō are attributed to Koen.

- Taisan'ō 太山王 (one of the Ten Kings of Buddhism), Shirokuzō 司録像, and Shimeizō 司命像 (all made around +1259) at Byakugōji Temple 白毫寺 in Nara.

- Followers of the Four Celestial Guardians (Shitennō Kenzoku 四天王眷属) along with Follower of Tamonten 多聞天 (now at Atami Art Museum, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan). Made in +1267.

- Fudō Myō-ō 不動明王 and Fudō’s Eight Attendants (Fudō Hachi Dai Dōji 八大童子) at Kannonji Temple 観音寺 in Tokyo; made in +1272.

- Monju Bosatsu 文殊菩薩 and Four Attendants (Monju Gosonzō 文殊五尊像) in the Nakamura Collection in Tokyo. Made in +1273.

- Aizen Myō-ō 愛染明王 at Jingo-ji Temple 神護寺 in Kyoto. Made in +1275.

UNKEI’S GRANDSON

Kōsei 康清 (Kosei). Grandson of Unkei 運慶. Son of Kōshō 康勝. Active +1237-1254. Awarded Hōgen 法眼 rank in his career.

- Appentice to his uncle Tankei 湛慶 during the restoration of the statuary at Sanjūsangendō (Rengeōin Temple 蓮華王院) in Kyoto between +1251-1254.

- Jizō Bosatsu 地蔵菩薩 at Tōdaiji Temple 東大寺 in Nara, inside the Nembutsudō 念仏堂 (Invocation Hall) dedicated to the soul of his grandfather Unkei, his father Kōshō, and others.

UNKEI’S GRANDSON

Kōshun 康俊 (Koshun). Grandson of Unkei. Son of Unjo 運助. Active first half 14th century. Many extant works. Both Kōshun and his son Kōsei considered themselves as Nara Busshi, attached to the Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 in Nara, but their work extended far to the south into Kyushu. Kōshun in fact established his own branch workshop in Kyoto named Shichijō Higashi Bussho 七条東仏所.

- Jizō Bosatsu 地蔵菩薩 at Hōkōin Temple 宝光院 in Nara Prefecture. Dated +1315.

- Shōtoku Taishi 聖徳太子 at Atami Art Museum, made +1320.

- Shitennō 四天王 at Eikōji 永興寺, Oita Prefecture, made +1321-22.

- Monju Bosatsu 文殊菩薩 at Hannya-ji Temple 般若寺, Nara, made +1324

- Fugen Enmei Bosatsu 普賢延命菩薩 at Ryūdenji Temple 龍田寺, Saga Prefecture, made +1326.

- Hachiman 八幡 (Shinto god) as a Buddhist priest, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, made +1328

- Monju Bosatsu 文殊菩薩 and Four Attendants (Monju Gosonzō 文殊五尊像) at Daikōji Temple 大光寺, Miyazaki Prefecture, made in +1348

- Fudō Myō-ō 不動明王 at Fukushōji Temple 福祥寺, Hyōgo Prefecture, made +1369.

UNKEI’S LATER DESCENDANTS

- Kōsei 康成 (Kosei). Great grandson of Unkei. Grandchild of Unjo 運助. Son of Kōshun. Both Kōsei and his father Kōshun considered themselves as Nara Busshi, attached to the Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 in Nara, but their work extended far to the south into Kyushu.

- Jizō Bosatsu 地蔵菩薩, formerly in Hara Collection (Tokyo), made in +1336.

- Nio (Niō) 仁王 Guardians, Kimpusenji Temple 金峰山寺, Mt. Yoshino 吉野, Nara Prefecture, made in +1338

- Yakushi Nyorai 薬師如来, Kimpusenji Temple 金峰山寺, Mt. Yoshino 吉野, Nara Prefecture, made in +1353.

- Kōyo 康誉 (Koyo). Fifth-generation descendant of Unkei and head busshi of Tōji Temple 東寺仏師 in Kyoto. Active in the 14th century. Kōyo’s extant statue of Dainichi Nyorai 大日如来 at Henjōji Temple 遍照寺 in Tochigi Prefecture, made in +1346, has a heavy, fleshy body and elaborately carved robes, but art historians consider it to be conventional and rather stiff. Kōyo established an important Keiha branch school in Kyoto known as the Shichijō Nishi Bussho 七条西仏所.

- Kankei 覚慶. In the late 14th century, the sculptor Kankei split from the Keiha to form an independent guild called the Tsubai Bussho 椿井仏所, from which sprang numerous sculptors.

Keishun 慶俊 Keishun 慶俊

Unkei’s apprentice, unrelated by blood. Active in the first half of the 13th century. Keishun hailed from Tajima Province (modern-day Hyōgo Prefecture). During his lifetime he gained the rank of Hokkyō, the third highest title awarded to sculptors.

Keishun is the sculptor of the extant statue of Amida Nyorai (Buddha) 阿弥陀如来 at Senjūji Temple 千手寺 in Mie Prefecture, made in +1240. The statue is 97.3 centimeters in height, made of wood with applied lacquer and gold leaf. See the photo at right.

Jōkei 1 定慶 (Jokei). A member of the Kei school, although his lineage is unclear. Active in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. Curiously, another important sculptor of the period used the same name, so scholars label them as Jōkei 1 and Jōkei 2. Some theorize that Jōkei 1 was the apprentice of Kōkei (father of Unkei); others suggest he was Unkei’s second son, Kōun, working under an assumed name. Jōkei 1 is credited with creating his own unique style, blending both the realism of the Kei school with the artistic styles of Sung-dynasty China. Extant work includes: Jōkei 1 定慶 (Jokei). A member of the Kei school, although his lineage is unclear. Active in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. Curiously, another important sculptor of the period used the same name, so scholars label them as Jōkei 1 and Jōkei 2. Some theorize that Jōkei 1 was the apprentice of Kōkei (father of Unkei); others suggest he was Unkei’s second son, Kōun, working under an assumed name. Jōkei 1 is credited with creating his own unique style, blending both the realism of the Kei school with the artistic styles of Sung-dynasty China. Extant work includes:

- Sanju 散手 mask (Bugakumen 舞楽面 mask), dated +1184, Kasuga Shrine 春日大社, Nara. The mask is admired for its exceptional realism and plasticity.

- Statue of Indian Buddhist Layman Yuima 維摩, dated +1196, Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺, Nara. See photo below.

- Seated Monju Bosatsu 文殊菩薩, dated +1196, Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺, Nara. See photo below.

- Bonten 梵天, dated +1202, Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺, Nara. Wood, H = 181.3 cm, deeply carved folds in an elegant robe, reflecting the artistic influence of China’s Song 宋 (Jp. = Sō) dynasty. See photo below.

- Niō Guardians 仁王, 13th Century, Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺, Nara. The two are attributed to Jokei. H = 161.5 cm, painted wood, crystal eyes. See photos below.

Bonten 梵天, dated +1202, by Jōkei 1.

Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺, Nara. Wood, H = 181.3 cm, deeply carved folds & elegant robe.

Reflects artistic influence of China’s Song 宋 dynasty. Important Cultural Property.

Indian Buddhist Layman Yuima 維摩 by Jōkei 1, National Treasure

Dated +1196, H = 88.5 cm, Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺, Nara.

This statue, together with the Monju statue below, depict the scene when Monju

was sent by Buddha to visit Yuima, who was sick in bed; the two then conversed.

For more details on Yuima, see Yuima entry on the Monju Bosatsu page.

Seated Monju Bosatsu 文殊菩薩 by Jōkei 1.

Dated +1196, Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺, Nara.

Wood, H = 94 cm, National Treasure.

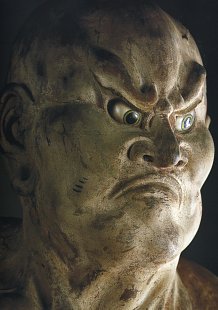

Agyō 阿形 H = 154 cm, aka Kongō Rikishi 金剛力士.

Attributed to Jōkei 1. Wood, with paint applied. Kamakura Era.

Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺, Nara. National Treasure.

See Niō Guardians for details on Agyō.

Ungyō 吽形 H = 153.7 cm, aka Kongō Rikishi 金剛力士.

Attributed to Jōkei 1. Wood, with paint applied. Kamakura Era.

Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺, Nara. National Treasure.

See Niō Guardians for details on Ungyō.

Inkō 院康 (Inko). At Kakuon-ji Temple 覚園寺 in Kamakura, there is a wooden statue of Ashuku Nyorai (see below photo), reportedly carved in 1322 AD by a local sculptor named Inkō 院康 (years of birth/death unknown). During the Kamakura Era, there were sculptors whose name began with "in," like Inkei and In'no. Inkei fashioned a sedentary statue of Priest Ken'nichi Koho (enshrined at Kencho-ji Temple in Kamakura), while In'no is thought to be the creator of a statue of Priest Sho-in Myogen (enshrined at Engaku-ji Temple, also in Kamakura). Both are considered excellent sculptors of the 14th century, and belong to a school of sculpture called the "In" school. <above paragraph courtesy of Kondo Takahiro>

Ashuku Nyorai, Treasure of Kakuon-ji 覚園寺 Temple (Kamakura).

Wood Carving attributed to sculptor Inkō 院康. H = 115 cm (about 3.77 feet).

Dated 1322 AD. Deity holding medicine jar in left hand.

The statue of Ashuku Nyorai (see above photo) enshrined at Kakuon-ji Temple in Kamakura was originally thought to be Yakushi Nyorai (the Medicine Buddha), for Yakushi is typically shown holding a medicine jar in the left hand. But at some point, the temple priests discovered an inscription hidden inside the head of the statue, which gave both the name of the deity (Ashuku) and the artist (Inko 院康) who carved the statue. Nevertheless, Yakushi Nyorai is also closely associated with the eastern quarter -- Yakushi is the Lord of the Eastern Pure Land of Lapis-Lazuli, while Ashuku is the Lord of the Eastern Land of Exceeding Great Delight. In some traditions, Yakushi and Ashuku are said to inhabit the same body. Ashuku is also one of the Five Wisdom Buddha.

Jōkei 2 定慶 (Jokei) Jōkei 2 定慶 (Jokei)

A member of the Kei school of Japanese sculpture. Jōkei 2 was born in +1184. Curiously, another important sculptor, slightly older, used the same name, so scholars label them as Jōkei 1 and Jōkei 2. Jōkei 2 is credited with creating his own unique style, blending both the realism of the Kei school with the artistic styles of China’s Sung Dynasty. His work is decidedly “delicate” in comparison to that of Jōkei 1, yet his Niō statues are quite dynamic and powerful. During his life, he rose to Hokkyō rank and received the honorary title Bettō 別当 (workshop director, project director).

- Shaka Nyorai 釈迦如来, Suzuki Collection (Tokyo), made in +1223

- Bishamonten 毘沙門天, Tokyo University of Arts, made in +1224

- Six Manifestations of Kannon Bosatsu 六観音, made in +1224, at Daihō-onji Temple 大報恩寺 (Kyoto). See photos below. Also visit the Kannon page for historical notes on the Six Kannon.

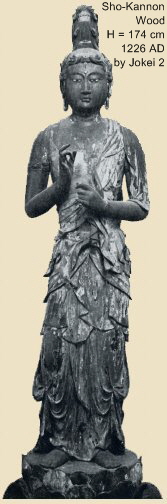

- Shō-Kannon 聖観音, made in +1226, at Kuramadera 鞍馬寺, Kyoto. See photo at right.

- Niō Guardians 仁王, made in +1242, at Sekigan-ji Temple 石龕寺 in Hyōgo Prefecture.

- Niō Guardians 仁王, made in +1256, at Ōzōji Temple 横蔵寺, Gifu Prefecture.

Six Kannon by Jōkei 2

Six Kannon 六観音 by Jōkei 2 定慶, Dated +1224

Wood, Treasures of Daihō-onji Temple 大報恩寺 (Kyoto)

Shō Kannon 聖観音, Senju Kannon 千手観音, Batō Kannon 馬頭観音

Six Kannon 六観音 by Jōkei 2 定慶, Dated +1224

Wood, Treasures of Daihō-onji Temple 大報恩寺 (Kyoto)

Jūichimen Kannon 十一面観音, Juntei Kannon 准胝観音, Nyoirin Kannon 如意輪観音

See Above Six Photos

Six Kannon to Protect All Sentient Beings in the Six Realms of Rebirth

Six Kannon 六観音 by Jōkei 2 定慶, Dated +1224, Wood, Daihō-onji Temple 大報恩寺 (Kyoto)

- Beings in Hell, Shō Kannon 聖観音, 177.9 cm

- Hungry Ghosts, Senju (1000-Armed) Kannon 千手観音, 180.0 cm

- Animals, Batō (Horse-Headed) Kannon 馬頭観音, 173.3 cm

- Ashura, Jūichimen (11-Headed) Kannon 十一面観音, 180.6 cm

- Humans, Juntei Kannon 准胝観音, 175.7 cm

- Deva, Nyoirin Kannon 如意輪観音, 96.1 cm

Note One: See Six Realms for many more details. Note Two: Professor Sherry Fowler (U. of Kansas) has done extensive research on the Six Kannon of Daihō-onji 大報恩寺. Note Three: Like Japanese groupings of the Six Jizō Bosatsu, the Kannon in Japan is also shown in six basic forms to protect people in all six realms of rebirth (reincarnation). The six forms of Kannon, of Chinese origin, come in at least three different groupings. The earliest known reference to the six comes from a Chinese Tendai text entitled 摩訶止観 (Jp. = Makashikan; circa 594 AD), translated as “Great Concentration and Insight.” By the early-mid 10th century AD, effigies of the Six Kannon were used in Japan to pray for the welfare of the dead. The six also appear frequently in the Rokujikyō Mandara 六字経曼荼羅 of Japan’s Shingon sect. (Source JAANUS) Also visit our Kannon page for more historical notes on the Six Kannon.

Closeup of Juntei Kannon, one of the Six Kannon, by Jōkei 2

Kōyū 幸有 (Koyu). Nearly nothing is known of this busshi or his lineage. But the powerful and heroic style of Unkei’s Keiha school is very apparent. Another notable feature is the wavy folds in the robe’s drapery, characteristic of Song-dynasty artistic tastes. This statue is considered a masterpiece of the Kamakura period. See photo immediately below.

King Shokō-ō 初江王, the 2nd Judge of Hell, by Kōyū 幸有.

H = 100 cm, Wood, Dated +1251, Treasure of Ennō-ji Temple 円応寺.

Now housed at Kamakura Museum (Kamakura Kokuhokan).

|

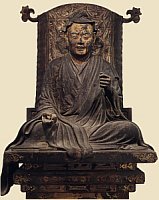

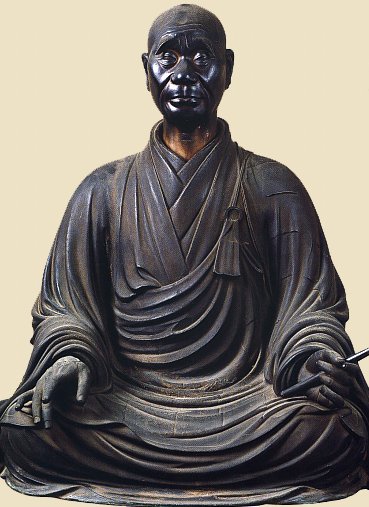

Monk Eison 叡尊 by Zenshun

Dated +1280, Saidaiji Temple

Eison resided at this temple.

Painted wood, H = 89.4 cm

|

|

Zenpa School 善派 Zenpa School 善派

An innovative branch of the Keiha School that emerged in the Kamakura period. Called the ZEN school, for most of its artists used the characther ZEN 善 in their names. The term HA 派 literally means school or group. It should be noted that the character ZEN 善 in their names is different from the character for Zen 禅 Buddhism. There is no implied relationship between the Zenpa artists and the Zen religious sect. The Zenpa school was essentially an offshoot of the Keiha school, and today its artists are classified as part of the Kei tradition. Active mainly in the Nara area in the early to mid-Kamakura period (13th century). Its artists displayed a wider range of stylistic variation than did other schools. They were closely connected with Saidaiji Temple 西大寺 in Nara, where they maintained close links with the monk Eison 叡尊 (1201-1290), who gave them many commissions. Zenpa artists were apprenticed according to the traditional workshop system, and the senior position, Daibusshi 大仏師, was passed on by inheritance. When Unkei and other Kei artists moved to Kyoto in the early 13th century, the Zen artists remained in Nara to carry on the tradition of the Nara Busshi. Important members include:

- Zen'en 善円 (dates unknown)

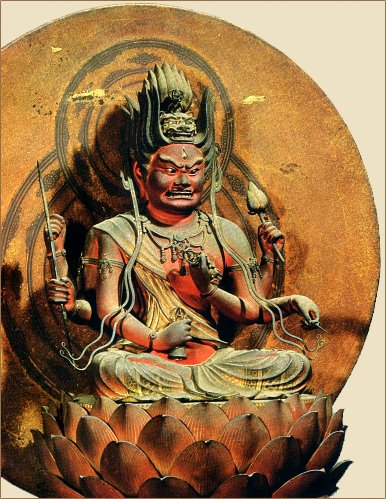

Aizen Myō-ō 愛染明王, dated +1247, by Zen'en, under the sponsorship of Monk Eison, at Saidaiji Temple 西大寺, Nara. Zen'en’s work is noted for technical excellence. See photo below.

Shaka Nyorai 釈迦如来, dated +1225, Tōdaiji Temple 東大寺, Nara. See photo below.

- Zenkei 善慶 (d. +1258)

Shaka Nyorai 釈迦如来, dated + 1249, Saidaiji Temple 西大寺, Nara. See photo below. Sponsored by Monk Eison. Zenkei’s work is noted for its delicate sensitivity. Historical records do not reveal if there was any close connection between Zen’en and Zenkei. Also a statue of Yakushi Nyorai 薬師如来, Shōfukuji Temple 正福寺 (??), Awaji Island 淡路, Hyōgo Prefecture.

- Zenshun 善春 (dates unknown). Son of Zenkei (see above). His extant works include the portrait statue of Eison 叡尊, made in +1280, at Saidaiji Temple 西大寺, Nara. See photos below. Also a statue of Prince Shōtoku Taishi 聖徳太子 at Gokuraku-bō Temple 極楽坊 (once part of the now lost Gangōji Temple 元興寺) in Nara. Zenshun’s work is noted for its realistic portraiture.

Shaka Nyorai 釈迦如来, by Zenkei, Unpainted wood with gold leaf patters

H 167 cm. Dated +1249. Saidaiji Temple 西大寺, Nara.

Aizen Myō-ō 愛染明王, by Zen’en, Painted wood. H 42.4 cm. Dated +1247

Aizendō, Saidaiji Temple 西大寺, Nara. Photo courtesy Heibonsha.

Aizen Myō-ō 愛染明王, by Zen’en

Same statue as prior photo. Photo courtesy 日本の仏像 magazine.

Shaka Nyorai 釈迦如来, dated +1225, by Zen’en

Wood, H = 29 cm, Tōdaiji Temple 東大寺, Nara. Photo from temple catalog.

Above and Below. Monk Eison 叡尊 by Zenshun.

Dated +1280, Saidaiji Temple 西大寺, Nara

Painted wood, H = 89.4 cm. Eison resided at this temple.

Photo courtesy 日本の仏像 magazine.

Closeup of above photo.

NOTEBOOK. Not yet incorporated into site page.

Below text courtesy JAANUS. Chinsou 頂相. Alt. reading chinzou. Lit. head's appearance. A naturalistic portrait, sculpted or painted, of a Zen 禅 master's head. Chinsou can be divided into two types depending on their function. First are inka 印可, given by a master to his disciple as a certificate of the student's attainment of spiritual awareness and as a symbol of the clear and unbroken lineage of a sect. These portraits often include hougo 法語, or words of religious enlightenment, inscribed by the priest depicted. A portrait done in a realistic and detailed style, together with an inscription, provided the disciple with both the tangible presence and the inspiration of the teaching of his master long after personal relations were severed through parting or death. Second are keshin 掛真 which were to be hung or placed together with imaginary portraits of Zen patriarchs *zenshuu soshizou 禅宗祖師像 in either the Dharma Hall *hattou 法堂, or main gate *sanmon 三門, of Zen sect temples in connection with memorial services. Chinsou of this second type were made after the master's death and the inscription was usually added by a close contemporary. Chinsou sculpture belongs entirely to the keshin category. The desire to symbolize the personal relationship between sitter and disciple recipient, or to memorialize a master for later followers, necessitated a high degree of verisimilitude. Moreover, the chinsou artist was encouraged to go beyond the mere physical likeness to capture something of the inner spirit of his subject. Painted chinsou are known in three formats. The most orthodox type show the priest wearing his full robe noue 衲衣 and surplice kesa 袈裟, seated en face in a large upholstered wooden armchair *kyokuroku 曲ろく, holding a bamboo baton shippei 竹箆 or whip kyousaku 警策 in the right hand. He is often shown with legs tucked under and shoes on a small footrest kutsudoko 沓床. A second format which evolved later was the half-length or bust portrait hanshinzou 半身像 that focuses on the individualistic details of the face. Typically in such depictions, even the hands of the priest will be hidden beneath the voluminous sleeves except for the exposed thumb of the left-hand. Orthodox painted chinsou feature a naturalistic style with fine linear details and a full range of colors, although some later examples are rendered more simply in ink monochrome. The third category may be termed special formats, including portraits of a master walking or resting *kinhinzou 経行像 and usually including landscape elements, as well as bust portraits in a circular framework *ensouzou 円相像. The chinsou tradition is said to have begun in China, possibly initiated by the needs of Japanese students. In the late 12c when Japanese priests returned from study in China, they often brought chinsou of their Chinese masters. A representative early example is the anonymous 1238 portrait of Bujun Shiban 無準師範 (Alt.reading Mujun Shihan, Ch: Wuqun Shifan) presented to the Japanese priest Bennen Enni 弁円円爾 (1202-80), who on his return founded Toufukuji 東福寺. Initially Japanese Zen temples lacked the artists to produce chinsou and therefore employed portrait specialists from other sects. A good example is the 1265 portrait of Gottan Funei 兀庵普寧 (Ch: Wuan Puning, 1197-1276) by Takuma Chouga 託磨長賀, priest-painter of the esoteric temple Shoudenji 正伝寺. Early chinsou are unsigned, a fact that has greatly complicated the issue of determining the artist and even country of origin. Perhaps the earliest signed chinsou by a Japanese painter priest of a Zen sect is the portrait of Muhon Kakushin 無本覚心 by Kakue 覚恵 (Koukokuji 興国寺). By the mid 14c, Japanese artists were producing high quality chinsou as demonstrated by the anonymous 1334 portrait of Daitou Kokushi 大燈国師 (Daitokuji 大徳寺) and the 1349 portrait of Musou Kokushi 夢窓国師 by his desciple Mutou Shuui 無等周位 (Tenryuuji 天竜寺). From the late 14c painter-priests such as Minchou 明兆 (1351-1431) produced large numbers of excellent chinsou at the ateliers of major Zen temples. The creative vigor of the chinsou tradition continued in the 15c, exemplified by the remarkable portrait of *Ikkyuu 一休 (Daitokuji 大徳寺) attributed to his disciple Bokusai 墨斎 (?-1492). Chinsou were produced throughout the Edo period, with the portraits of the Oubaku 黄檗 (Ch: Huanglo) sect of special note. <end JAANUS quote>

RESOURCES

- JAANUS. Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System. Online database devoted to Japanese art history. Compiled by the late Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent, it covers both Buddhist and Shintō deities in great detail and contains over 8,000 entries.

- Dr. Gabi Greve. See her page on Japanese Busshi. Gabi-san did most of the research and writing for the Edo Period through the Modern era. She is a regular site contributor, and maintains numerous informative web sites on topics from Haiku to Daruma. Many thanks Gabi-san !!!!

- Heibonsha, Sculpture of the Kamakura Period. By Hisashi Mori, from the Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art. Published jointly by Heibonsha (Tokyo) & John Weatherhill Inc. A book close to my heart, this publication devotes much time to the artists who created the sculptural treasures of the Kamakura era, including Unkei, Tankei, Kōkei, Kaikei, and many more. Highly recommended. 1st Edition 1974. ISBN 0-8348-1017-4. Buy at Amazon

. .

- Classic Buddhist Sculpture: The Tempyo Period. By author Jiro Sugiyama, translated by Samuel Crowell Morse. Published in 1982 by Kodansha International. 230 pages and 170 photos. English text devoted to Japan’s Asuka through Early Heian periods and the development of Buddhist sculpture during that time. ISBN-10: 0870115294. Buy at Amazon.

- The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture, AD 600-1300. By Nishikawa Kyotaro and Emily J Sano, Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth) and Japan House Gallery, 1982. 50+ photos and a wonderfully written overview of each period. Includes handy section on techniques used to make the statues. The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture (AD 300 - 1300)

. .

- Comprehensive Dictionary of Japan's National Treasures. 国宝大事典 (西川 杏太郎). Published by Kodansha Ltd. 1985. 404 pages, hardcover, over 300 photos, mostly color, many full-page spreads. Japanese Language Only. ISBN 4-06-187822-0.

- Bosatsu on Clouds, Byōdō-in Temple. Catalog, May 2000. Published by Byōdō-in Temple. Produced by Askaen Inc. and Nissha Printing Co. Ltd. 56 pages, Japanese language (with small English essay). Over 50 photos, both color, B&W. Some photos at this site were scanned from this book. Of particular use when studying the life and work of Jōchō Busshi.

- Visions of the Pure Land: Treasures of Byōdō-in Temple. Catalog, 2000. Published by Asahi Shimbun. Artwork from Byōdō-in Temple. 228 pages, Japanese language with English index of works. Over 100 photos, color and B&W. Some photos at this site were scanned from this book. No longer in print. Of particular use when studying the life and work of Jōchō Busshi.

- Numerous Japanese-language temple and museum catalogs, magazines, books, and web sites. See Japanese Bibliography for extended list. Also relied on Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺 (Horyuji) catalogs and Asuka Historical Museum.

JAPANESE WEB SITES JAPANESE WEB SITES

|