|

|

|

|

VAJRAYANA (TANTRIC) SCHOOL

ALSO SEE: ESOTERIC BUDDHISM IN JAPAN

Vajrayana Buddhism = Tantric Buddhism = Esoteric Buddhism

In Japan, Esoteric Buddhism is known as Mikkyō 密教 (Mikkyo)

This is a side page. Return to Parent Page.

Overview | Hinduism | Theravada | Mahayana | Vajrayana  | Rifts | Rifts

RELATED PAGES: Early Buddhism in Japan | Comparing Schools | Guide to Buddhism in Japan

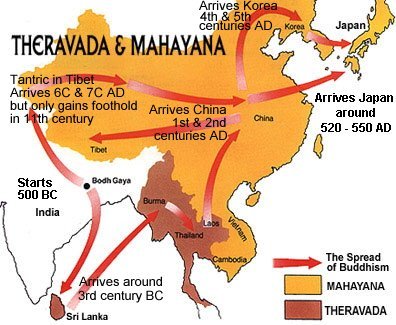

Map courtesy of Buddhanet

Vajrayana School, Tantric Buddhism Vajrayana School, Tantric Buddhism

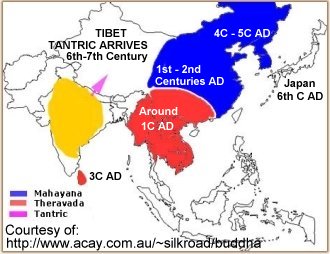

The last of the three main schools of Buddhism, Vajrayana traditions developed around 500 AD out of Mahayana teachings from northwest India. Vajra in Sanskrit means diamond (lit. adamantine, unsplittable), while yana means vehicle. Vajrayana is thus translated as "Diamond Vehicle." In English it is also known as Tantric Buddhism or Esoteric Buddhism, due to its reliance on sacred texts called tantras. From India it spread to Tibet and China with only brief success (but centuries later takes strong root in Tibet), and finally it arrives in Japan around the early 9th century, thanks to the efforts of the Japanese priests Saichō 最澄 and Kūkai 空海. Saichō (767 - 822) founded Japan's Tendai 天台 sect, while Kūkai 空海 (774 - 835 AD; aka Kōbō Daishi) founded Japan’s Shingon Sect 真言 of Esoteric Buddhism 密教 (Mikkyō, Mikkyo). During their lifetime, both monks visited China, where the Tantric texts had been translated into Chinese, and returned to Japan with many texts and artworks.

Today the teachings of the Vajrayana school are practiced mostly in Tibet, although Japan’s Shingon 真言 and Tendai 天台 sects still retain many facets of Vajrayana Buddhism (known as Kongōjō, Kongojo, or Kongojyo 金剛乗) in Japan. Vajrayana's main claim is that it enables a person to reach Nirvana (freedom from suffering) in a single lifetime -- rather than passing through countless lives before achieving salvation. In Theravada Buddhism, which stresses meditation and the monastic path to enlightenment (laity excluded), followers hope to gain enough merit in this life to reincarnate into the next with better karma -- thereby moving one step closer on the long path to Nirvana. Mahayana Buddhism promises salvation to both monks AND LAITY, but it too proclaims that believers, whether monk or laity, must gain merit over the course of innumerable lives before the ultimate spiritual level can be attained. Vajrayana promises the "fast path" to Buddhahood -- a path that, in some Vajrayana traditions, brings magical powers. (Author’s Note: This is an over-simplification. Modern Mahayana sects worshipping Amida Nyorai also offer a quick path to Buddhahood. The key practice for Amida devotees is simply to chant Amida’s name, “Namu Amida Butsu,” for Amida vowed that whoever calls this name with faith shall be reborn in a paradise called the Pure Land. Those who are reborn in Amida’s Western Pure Land -- a land devoid of worry or toil -- can focus their energies on attaining Buddhahood. Here, in the Pure Land, they no longer need worry about the Six States of Existence -- for rebirth in the Pure Land means they are no longer trapped in the cycle of birth and death (Skt. samsara).

Vajrayana Buddhism involves esoteric visualizations, symbols, and complicated rituals that can only be learned by study with a master. This explains why Vajrayana Buddhism is also referred to as Esoteric Buddhism. Vajrayana Buddhism lays great emphasis on mantras (incantations), mudras (hand gestures) and mandalas (diagrams of the deities and cosmic forces), as well as on magic and a multiplicity of deities. In Vajrayana traditions, there is no external reference point for "good and evil," and the role of the teacher thus becomes critical. In the West, the complete devotion to the teacher required of the acolyte is sometimes referred to as "guru yoga."

The generally accepted view is that Vajrayana Buddhism developed out of Mahayana teachings in northwest India around 500 AD, then gathered momentum after 600 AD. It appears to have flowered around the 8th century in Uddyana, a kingdom near Peshawar in modern Pakistan, where King Indrabhuti was initiated into the Tantric mysteries. It was also practiced widely in Bengal during the Pala dynasty (750-1150 AD). By the 8th century, the Tantric texts were translated into Chinese. The Chinese teachings were eventually introduced to Japan by the Japanese priest Kūkai (also known as Kōbō Daishi, 774 - 835 AD), the founder of Japan’s Shingon Sect, and by Saichō (767 - 822), the founder of Japan's Tendai 天台 sect. In addition, Japan’s Shugendō 修験道 mountain cults (founded by the 7th century holy man En no Gyōja 役行者) incorporated many esoteric beliefs and practices. The Shugendō cult stresses physical endurance as the path to enlightenment. Shugendo's extreme rituals include walking on red-hot coals, chanting while sitting under ice-cold waterfalls, or hanging by the feet from the edge of a cliff.

Vajrayana differs significantly from the Theravada and Mahayana schools, but it nonetheless incorporates many ideas and practices from both schools. For example, Vajrayana does not reject the basic teachings of the Historical Buddha. Like the Theravada and Mahayana schools, its ultimate aim is liberation from suffering, the abandonment (transcendence) of self, and the renouncing of all attachment to conscious existence. Like the Theravada and Mahayana schools, it proclaims that the physical world is illusory. Vajrayana differs significantly from the Theravada and Mahayana schools, but it nonetheless incorporates many ideas and practices from both schools. For example, Vajrayana does not reject the basic teachings of the Historical Buddha. Like the Theravada and Mahayana schools, its ultimate aim is liberation from suffering, the abandonment (transcendence) of self, and the renouncing of all attachment to conscious existence. Like the Theravada and Mahayana schools, it proclaims that the physical world is illusory.

Theravada says life is suffering caused by attachment, and reincarnation is to return to suffering. Mahayana says life can be joyful, but suffering still arises due to zealous desires and fears. Vajrayana says utilize all situations for spiritual awakening -- do not suppress energy, but rather transform it.

Writes one site reader: “As a fighter in the martial arts, you must transform energy rather than suppress it. Suppressing energy is force against force. If you are the weaker force, you get destroyed -- one force completely dominates the other. Instead, the idea is to allow both to exist by transforming both into different states.”

In the West, Tantric Buddhism is known primarily for the sexual practices of certain Tantric sects from India, whose adherents strive to transform erotic passion into spiritual ecstasy. In this branch of Vajrayana Buddhism, followers are taught not to suppress their desires but to indulge in them. Where Theravada renounces the desires of the body, Vajrayana teaches indulgence in sensual impulses. Where Mahayana teaches us to reject and deny our desires, Vajrayana teaches us to accept and revel in them. (The same reader quoted above says: “One is taught not to reject and deny desires, but rather to transcend them. In some cases that calls for a student to experience desires in order to realize the inherent emptiness in the senses. Once the emptiness is realized, accepting or rejecting them is also empty.”)

The erotic form of Tantric Buddhism is no longer, to my knowledge, practiced widely in modern India, Tibet (the stronghold of Tantric traditions), or elsewhere.

|

Esoteric Sects in the Heian Era introduce many Hindu deities to Japan and promote the merger of Kami-Buddha practices and beliefs. Esoteric deities are portrayed in great number in the artwork of coming centuries.

Dainichi Nyorai. The supreme deity of

Japan’s Esoteric Sects, positioned in center of most mandalas. Photo from Nihon no

Koku-ou 日本の国王, Issue #066, Magazine 23495-5/31, Published 31 May 1998, by Asahi Shimbun. Appeared on page 7-172.

Fudo Myo-o

Wrathful emanation of Dainichi.

See description and citation

on the Fudo Myo-o page.

Saichō 最澄

Founder, Japan's Tendai Sect

Kamakura era (1224), wood, H = 66.9 cm, Kannonji Temple 観音寺 in Shiga 滋賀

Saichō was posthumously called

Dengyō Daishi 傳教大師.

Daishi 大師 means "Great Teacher."

Tendai 天台

Lit. = Heavenly Terrace School

Also called the Lotus Sutra School

Photo courtesy: Exhibit catalog

entitled "Faith and Syncretism: Saicho and

Treasures of Tendai." Published 2005 by the

Kyoto Nat’l Museum, Tokyo Nat’l Museum,

and The Yomiuri Shimbun.

Kūkai 空海

Founder, Japan's Shingon Sect

Posthumously called

Kōbō Daishi (Kobo Daishi) 弘法大師

Daishi means “Great Master”

Shingon 真言 (Lit. = True Word School)

Mt. Kōya 高野. Japan’s Shingon holy land is located on and around Mt. Kōya. The main temple is called Kongōbuji 金剛峰寺. In 822, Kukai was awarded exclusive control over Tōji Temple 東寺 in Kyoto, making it another center of Shingon practice and worship.

|

|

Esoteric Buddhism in Japan Esoteric Buddhism in Japan

Esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō 密教) is Japan’s version of Vajrayana, or Tantric Buddhism. It originated in India sometime in the 6th century and then spread quickly throughout Asia (see above text and map). Esoteric Buddhism wasn’t formally introduced to Japan until the early 9th century, but various esoteric forms of Kannon and other deities had already entered Japan (via China) during the 7th and 8th centuries.

Along with Hinayana and Mahayana Buddhism, Vajrayana is one of the three basic forms of Buddhism practiced in Asia today. It is especially strong in Japan and Tibet, and intricately connected with the mandala artform. In Japan, the main esoteric sects are the Shingon and Tendai sects -- both introduced to Japan from China in the early 9th century (see details below). All other forms of Buddhism are known as Exoteric Buddhism (Kenkyō 顕教), which represent the orthodox traditions of the old schools, including Japan’s Zen sects and Pure Land Amida sects. The term Kenmitsu Bukkyō 顕密仏教 refers to both exoteric and esoteric traditions.

Formal Introduction of Esoteric Practices. The Heian era (794-1185) was a groundbreaking time in Japanese Buddhism and Buddhist art, with two new sects introduced to the original Six Old Sects of Nara.

The newcomers were the esoteric Tendai 天台 and Shingon 真言 sects, both originating in China, brought back from China to Japan by Japanese priests Saichō 最澄 (Saicho, +766-822, founder of Japan's Tendai sect; also known as Konpon Daishi 根本大師 and Dengyō Daishi 伝教大師 or 傳教大師) and his contemporary Kūkai 空海 (Kukai, +774-835, founder of Japan's Shingon sect, also known as Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師). Both had visited China and brought back the teachings. Both played monumental roles in the merger of Shinto-Buddhist (Kami-Buddha) beliefs and the development of esoteric traditions and art. The latter is exemplified by mandala paintings and by statues of wrathful deities with multiple heads and arms, particularly the Myō-ō 明王, who serve Dainichi Buddha (Skt. = Mahavairocana), the central deity of Japan’s esoteric sects, and the incorporation of numerous Hindu deities into the Japanese pantheon. Nearly all Buddhist deities come in both esoteric and in exoteric forms.

Once transplanted to Japanese soil, both schools flowered with innovation. Saichō's Tendai sect attempted a synthesis of various Buddhist doctrines, including faith in the Lotus Sutra, esoteric rituals, Amida (Pure Land) worship, and Zen concepts. Tendai gained great court favor, rising to eminence in the late-Heian era. The Tendai temple-shrine multiplex is located around Mt. Hiei 比叡 (Shiga Prefecture, near Kyoto). The main temple is Enryakuji 延暦寺 and the central shrine is Hie Jinja 日吉神社 (also called Hiyoshi Taisha 日吉大社).

Shingon, in contrast, was predominantly esoteric. Its doctrines were mystical and occult, and required a high level of austerity. Elaborate and secret rituals were developed to help practitioners achieve enlightenment. Despite its complex practices, Shingon exerted a profound impact on religious art and the faith of the court and monastic orders. See Heian Era Statuary for details and photos. Shingon’s main temple is Kongōbuji (Kongobuji) 金剛峯寺, located at Mt. Kōya (Koya) 高野 in Wakayama Prefecture. In addition, Japan’s Shugendō 修験道 mountain cults (founded by the 7th century holy man En no Gyōja 役行者) incorporated many esoteric beliefs and practices.

Esoteric Buddhism’s main claim is that it enables a person to attain enlightenment in a single lifetime -- rather than passing through countless lives before achieving salvation (this is an over-simplification !!). To achieve this, it incorporates mystical visualizations, myriad symbols and deities, and complicated secret rituals that can only be learned by study with a master (guru) -- thus explaining the term “esoteric” Esoteric practice lays great emphasis on mantra (incantations), mudra (hand gestures), mandala (diagrams of the deities and cosmic forces), ritual ceremonies (to pray for rain, national security, the emperor’s well-being, etc.), as well as on magic and a multiplicity of deities.

Kūkai (aka Kōbō Daishi)

One of Japan’s Most Beloved Saints

Kūkai was the patriarch of the Shingon sect of Esoteric Buddhism. Shingon’s most prominent deity is Dainichi Buddha, whose symbol is the vajra (thus Vajrayana, the Sanskrit term for Diamond Vehicle).

Posthumously named Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師 (the Great Teacher), Kūkai remains one of Japan’s most beloved Buddhist teachers -- folklore says he attained Buddhahood before death. Portraits of him abound. The Japanese today tend to ignore doctrinal differences when honoring him. Kūkai traveled to China in 804, and was initiated in esoteric teachings by the Chinese priest Huiguo. Kūkai returned in 806, and by 816 obtained imperial sanction to construct his monastery on Mt. Kōya (Koya), a serene location on the Kii peninsula still considered a Holy Land and one of modern Japan's most popular pilgrimage sites.

He played an active role in many fields, performing rituals for the emperor, constructing a large reservoir in Shikoku for the common people, and establishing the first school for common citizens. His legend is riddled with folklore. He is credited with everything from inventing Japan’s kana script to introducing homosexuality. He is one of Japan’s most celebrated calligraphers, and supposedly published Japan’s first dictionary. He became a major patron of the arts, and reportedly founded hundreds of temples across Japan. The Shikoku Pilgrimage to 88 Sites is a popular pilgrimage attributed to Kūkai . Most devotees carry a staff bearing the words "we two walk together."

Three Main Schools of Buddhism Today

Buddhism as practiced today is still divided into three main schools -- (1) Theravada, meaning School of the Elders, but pejoratively known as Hinayana or Lesser Vehicle; (2) Mahayana, meaning Greater Vehicle; and (3) Vajrayana, meaning Diamond Vehicle; also known as Tantric or Esoteric Buddhism. “Yana” is the Sanskrit term for vehicle. The bewildering number of sects are categorized into one of the three schools.

- Theravada (Hinayana). Found mainly in Sri Lanka, Burma, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand. Often known as the Southern Traditions of Buddhism.

- Mahayana. Found mainly in China, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. Often known as the Northern Traditions of Buddhism.

- Vajrayana (Esoteric or Tantric Buddhism). Practiced mainly in Tibet, Nepal, and Mongolia, but in Japan has a strong hold with the Shingon 真言, Tendai 天台, and Shugendō 修験道 sects. In Japan, Esoteric Buddhism is known as Mikkyō (Mikkyo) 密教). Along with Mahayana Buddhism, the Vajrayana traditions are often referred to as the Northern Traditions of Buddhism.

LEARN MORE

- Groner, Paul. Saicho: The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School. University of Hawaii Press, 2000 (originally published by University of California, Berkeley, 1984).

- Groner, Paul. A Medieval Japanese Reading of the Mo-ho Chih-Kuan: Placing the Kanko Ruijii in Historical Context. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies (1995) 22/1-2. <Web resource; last accessed on 15 Feb. 2011>

- Faith and Syncretism: Saicho and Treasures of Tendai. Kyoto National Museum catalog, 2005. <Web resource; last accessed on 15 Feb. 2011>

- Treasures of a Sacred Mountain. Kukai and Mount Koya. The 1200-Year Anniversary of Kukai’s Visit to Tang-Dynasty China. Tokyo National Museum, exhibit catalog, 2004. Also see Sacred Treasures of Mount Koya: The Art of Japanese Shingon, University of Hawaii Press (May 2002). <Web resource; last accessed on 15 Feb. 2011>

- Kim, Yung-Hee. Songs to Make the Dust Dance: The Ryojin Hisho of Twelfth-Century Japan. University of California Press, 1994. <Web resource; last accessed on 15 Feb. 2011>

NOT YET FILED OR EDITED

Source: JAANUS, Shōrai Mokuroku 請来目録

Lit. = List of objects acquired and brought back. Lists and other records of Buddhist objects brought back to Japan from China by Japanese students of Buddhism from the Nara through Heian periods (7c-10c). Statuary objects, sutras, religious implements and writings are the major items listed (see *shouraihin 請来品). Most well-known lists were complied in the 9c by the Eight Esoteric Masters who Studied in Tang China (Nittou hakke 入唐八家): *Kuukai 空海 (804-6 in China), Saichou 最澄 (804-5 in China), Ennin 円仁 (838-47 in China), Enchin 円珍 (853-8 in China), Enkou 円行 (838-9 in China), Jougyou 常暁 (838-9 in China), Eun 恵運 (842-7 in China) and Souei 宗叡 (862-5 in China). In 902, the cleric Annen 安然 gathered the shourai mokuroku of these eight masters into a single work, the SHO-AJARI SHINGON MIKKYOU BURUI SOUROKU 諸阿闍梨真言密教部類惣録 ("Combined Records of Shingon Esoteric Buddhism by Several Masters" ) of which copies still exist . These records are valuable sources of information on the Buddhist art of their period . Similar records were evidently compiled by later monks who brought back objects from Song China, but none of these have survived.

Mikkyō Bijitsu 密教美術

The art of esoteric Buddhism (mikkyō, mikkyou, mikkyo 密教). Esoteric Buddhism was introduced to Japan from China in the 8c by the monks Kuukai 空海, who founded the Shingon 真言 sect, and Saichou 最澄 who founded the Tendai 天台 sect. The most prominent deity in esoteric Buddhism is *Dainichi 大日, whose symbol, the vajra (kongou 金剛) gives us the Sanskrit term Vajrayana ( Vehicle of the diamond or). The influence of Hindu imagery is very strong, particularly in the multiple limbs and heads of some deities and also in the often violent aspect they present in the pursuit of good. Also female deities achieve a new prominence. The tolerance towards folk deities of Indian Buddhism made the establishment of the religion in Japan much smoother, since there was little initial conflict with the indiginous Shintou 神道 religion. The number of deities soared to huge figures as a result, and the co-existance of Buddhist temples and Shintou shrines on the same site is witness to this smooth syncretism, as is the existance of hybrid deities such as *Zaou Gongen 蔵王権現. The main form of artistic expression of esoteric Buddhism is the mandala, *mandara 曼荼羅, of which there are many different types. They can be two dimensional paintings or three dimensional arrangements of sculptures. These are a means of giving formal expression to the Buddhist ideals of symmetry, form and sense in life: the Sanskrit word tantra meaning system or model is applied. In both painting and sculpture the forms reflect Mahayana (Jp. Daijou 大乗) traditions from India, but there is a clear departure in the increased animation and violence of the figures, which is well illustrated by the silk hanging scrolls (*kakemono 掛物) of the Five Forceful Ones (*Godairiki Bosatsu 五大力菩薩) kept in the Kouyasan 高野山 treasure House on Mt. Kouya, which date from the 10c. By contrast there is a strain of sculpture in esoteric Buddhist art which exhibits a sense of contemplation and mystery, as exemplified by the sculptures of the Bodhisatvas of the Void (Godai Kokuuuzou Bosatsu 五大虚空像菩薩) in the Tahoutou 多宝塔 of Jingoji 神護寺 in Kyoto, dating from the 9c. Seated and rigid, they are the antithesis of the violent images seen elsewhere. Many works from this time were carved from single trees, reflecting the Japanese belief in their sanctity. These are often plain and heavy, in further contrast to the complex images of Mahayana Buddhist art. A fine example is the sculpture of the healing Buddha, Yakushi Nyorai ryuuzou 薬師如来立像 at Jingoji in Kyoto which dates from about 783.

|

|