|

|

Handbook on Viewing Buddhist Statues

A totally wonderful book. Some images shown on this page were scanned from this book; Japanese language only; 192 pages; 80 or so color photos. By author Ishii Ayako.

Click here to

buy book at Amazon |

|

|

English

|

Japanese

|

Chinese

|

Sanskrit / Pali

|

Korean

|

Tibetan

|

|

Immovable One

Mantra King

Wrathful Lord

Important Esoteric Deity

|

Fudō, Fudo

Fudō Myō-ō

Jōjū Kongō

不動

不動明王

|

Bù dòng, Bu Dong, Pu-tung, Āzhēluó, Bùdòng Míngwáng

不動

不動明王

|

Ācalanātha

Āryācalanātha

Achala Vidyaraja

Ācala-vidyā-rāja

Acalanatha means Unmoving Guardian

|

Budong, Pudong, Myeong wang, Myŏng wang

부동명왕

|

Mi yo wa, Lha khro bo, Drag-gshed (wrathful)

|

|

|

|

|

|

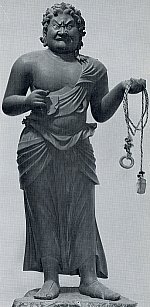

Fudō statue. Made by famed sculptor UNKEI 運慶 (d. 1223). Wood. Height 135.5 cm. Kamakura Period, 1195 AD. Located at Jyōraku-ji Temple 浄楽寺 (Jyourakuji, Jyorakuji) in Yokosuka City, Kanagawa Prefecture. Designated an Important Cultural Property 重要文化財. Photo Handbook by Ishii Ayako

Fudō’s Sanskrit Seed Syllable

KAN (Japanese pronunciation)

Fudō in Private Garden

Stone, circa 1910

Fudō Mask

Available online at

This J-Site

|

|

Fudō Myō-ō 不動明王 Fudō Myō-ō 不動明王

Also known as OFUDŌ-SAN or FUDŌ-SAMA

Origin = India. Manifestation of Dainichi Nyorai.

Member of the Myō-ō Group. Best known of the Myō-ō.

Fudō literally means “immovable” (his faith is immutable).

Patron of People Born in Zodiac Year of the Rooster.

Who is Your Patron Deity? Click Here to Find Out.

Fudō Mantra in Japanese

naa maku saa man daa ba sara nan kan

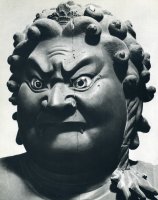

Fudō Myō-ō is the central deity in all Myō-ō groupings, and in artwork is positioned in the center. Fudō is a personification of Dainichi Nyorai, and the best known of the Myō-ō, who are venerated especially by the Shingon sect of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō 密教). Fudō converts anger into salvation; has furious, glaring face, as Fudō seeks to frighten people into accepting the teachings of Dainichi Buddha; carries “kurikara” or devil-subduing sword in right hand (representing wisdom cutting through ignorance); holds rope in left hand (to catch and bind up demons); often has third eye in forehead (all-seeing); often seated or standing on rock (because Fudō is “immovable” in his faith). Fudō is also worshipped as a deity who can bring monetary fortune. Also, Fudō's left eye is often closed, and the teeth bite the upper lip; alternatively, Fudō is shown with two fangs, one pointing upward and other pointing downward. Fudō’s aureole is typically the flames of fire, which according to Buddhist lore, represent the purification of the mind by the burning away of all material desires. In some Japanese sculpture, Fudō is flanked by two attendants, Kongara Dōji and Seitaka Dōji. In artwork, Fudō is often accompanied by Eight Great Youths. Fudō is also one of the 13 Deities 十三仏 (Jūsanbutsu) of the Shingon Sect in Japan. In this role, Fudō presides over the memorial service held on the 7th day following one's death.

Myō-ō is the Japanese term for Sanskrit "Vidyaraja," a group of warlike and wrathful deities known in English as the Mantra Kings, the Wisdom Kings, or the Knowledge Kings. Myō-ō statues appear ferocious and menacing, with threatening postures and faces designed to subdue evil and frighten unbelievers into accepting Buddhist law. They represent the luminescent wisdom of Buddhism, protect the Buddhist teachings, remove all obstacles to enlightenment, and force evil to surrender. Introduced to Japan in 9th century, the Myō-ō were originally Hindu deities that were adopted into Esoteric Buddhism to vanquish blind craving. They serve and protect the various Buddha, especially Dainichi Buddha. In most traditions, they are considered emanations of Dainichi Buddha, and represent Dainichi’s wrath against evil and ignorance. In Japan, among the individual Myō-ō, Fudō is the most widely venerated.

Sanskrit / Chinese Spellings and Translations

- Ācala-vidyā-rāja, Acala Vidyaraja (Sanskrit for Fudō Myo-o)

- Āryācalanātha 阿奢羅曩, Acalanatha (Sanskrit for “Immutable Lord” or “Immovable Lord”)

- 阿奢羅曩 (Chinese for Acalanatha);

also 不動尊, 無動尊, 阿奢囉逝吒, 不動使者

- 五明王 Wǔ Míng Wáng (Chinese for “Five Ming Wang”

or “Five Great Kings”)

- 不動 Bù Dòng (Chinese for Fudō, literally “unmoving, immovable, imperturbable”)

- 不動明王 Bù Dòng Míng Wáng (Chinese for Fudō Myo-o)

- 不動佛 (Chinese for the Sanskrit Ācala-vidyā-rāja”

- Central deity among the Five Great Myō-ō Kings; positioned in the center among the five

Japanese Spellings and Translations

- 明王 Myō-ō, Myou-ou, Myo-o, Myoo-oo (“Vidyaraja” in Sanskrit)

- 不動明王 Fudō Myō-ō, Fudo Myo-o, Fudou Myou-ou, Fudoo Myoo-oo

- 不動 Fudō, Fudo, Fudou, Fudoo

- 常住金剛 Jōjū Kongō, Fudō’s mystic esoteric name; lit. “Eternal and Immutable Diamond”

- 五大明王 Godai Myō-ō, Five Great Kings; Fudō is their leader; positioned in center

- Fudō is especially important to Japan’s Shingon Sect of Esoteric Buddhism

- Fudō often appears in Japanese artwork with two attendants named Kongara Dōji 矜羯羅童子 and Seitaka Dōji 制た迦童子; sometimes with two messengers named Kimkara 矜羯羅 and Cetaka 制吒迦; and sometimes with a group of eight messengers called Hachidai Dōji 八大童子

English Translations and Other Notes

Kings of Light, Kings of Luminescent Wisdom, Kings of Mystic Knowledge, Mantra Kings

ESOTERIC BUDDHISM IN JAPAN ESOTERIC BUDDHISM IN JAPAN

The teachings of Esoteric Buddhism are mystical and hard to understand, and require a high level of devotion and austerity to master. Elaborate and secret ritual practices (utilizing mantras and mudras and mandalas) are used to help partitioners develop and realize the eternal wisdom of the Buddha. This form of Buddhism is not taught to the general public, but is confined mostly to Buddhist believers, priests and those far along the path toward enlightenment.

Esoteric Buddhism's main practitioners in Japan were Priest Kukai (774 - 835 AD) and Priest Saicho (767 - 822 AD). Kukai, also called Kobo Daishi, founded the Shingon Sect of Esoteric Buddhism, while Priest Saicho founded the Tendai Sect. In the Esoteric sects, the Myo-o protect Buddhism and force its outside enemies to surrender. Today, the Myo-o are revered mainly by the Shingon sect, which emphasizes the Great Sun Sutra (Maha-vairocana Sutra) and worships Dainichi Buddha as the Central "All-Encompassing" Buddha. Indeed, the Myo-o are forms of Dainichi, and represent Dainichi's wrath against evil and ignorance.

GODAI MYŌ-Ō, FIVE GREAT KINGS

In contrast to the saintly images of the Buddha and Bodhisattva, images of the Myō-ō are ferocious and menacing, for their threatening postures and facial expressions are designed to subdue evil spirits and convert nonbelievers. They are often depicted engulfed in flames, which according to Buddhist lore, represent the purification of the mind by the burning away of all material desires. They carry vicious weapons to protect believers and subdue evil.

Among Myō-ō sculptures, the Godai Myō-ō (the grouping called the "Five Great Kings") is the most prevalent. Among individual Myō-ō, the most widely venerated and prevalent in Japan is Fudo "The Immovable." This group of five serve the Buddha, while another group of eight (Jp. = Hachidai Myō-ō) serve the Bodhisattva. In both groups, Fudo is their chief.

MONEY-WASHING FUDŌ. The Zeniarai Benten Shrine in Kamakura City is devoted to the goddess Benzaiten. At this shrine, believers "wash" their money in water to make it reproduce and increase. But there is another deity, known as Fudō Myō-ō, who can work the same miracle in Japan. This money-washing tradition is easy to understand for Benzaiten. She is the Japanese goddess (Hindu origin) of fortune, and shrines/temples devoted to her are always located near water (river, pond, lake, ocean). She is closely associated with dragons and serpents (Sanskrit = NAGA), who guard treasure. But why Fudō? His real symbol is fire. His aureole is almost always the flames of fire. He is also the central object of veneration for "GOMA," a Japanese fire ceremony still popular today in which defilements are symbolically burnt away. So why would people wash money under Fudō's protection? Because he washes away impurities? Maybe, perhaps, because drawings of Fudō show him standing on a rock rising from the sea -- for example, the drawing at Daigoji Temple (Kyoto) and the famous 1282 AD drawing by Shinkai of Fudō standing on a rock rising from the sea. Moreover, Kurikara, a dragon wound around a sword, may appear in paintings of Fudō. Also, both Kurikara and Fudō are found often near ascetic practice places, such as small waterfalls. Perhaps this is the reason. For more details on this topic, see the Fudō Money Washing Page by Gabi Greve (outside link).

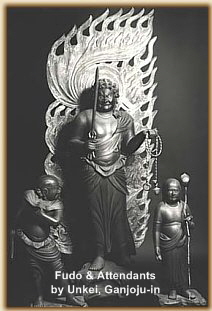

ABOVE: Fudō Myō-ō 不動明王 by UNKEI 運慶

Painted Wood, H = 136.5 cm. Dated +1186

Ganjoju-in (Ganjōju-in) Temple 願成就院, Shizuoka Pref. 静岡県

Photos courtesy Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art

By Hisashi Mori, from the Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art.

Published jointly by Heibonsha (Tokyo) & John Weatherhill Inc.

Hachidai Dōji 八大童子

Text Courtesy of JAANUS

http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/h/hachidaidouji.htm

Visit above JAANUS link for photos of the eight. Literally "Eight Great Youths." Eight attendants of either Monju Bosatsu 文殊 or, more commonly, Fudou Myouou 不動明王. The eight attendants of Fudou (Fudou Hachidai Douji 不動八大童子) are described in the HACHIDAI DOUJI HIYOU HOUBON 八大童子秘要法品, and their names are:

- Ekou Douji 慧光童子

- Eki Douji 慧喜童子

- Anokudatsu/Anokuta Douji 阿耨達童子

- Shitoku Douji 指徳童子

- Ukubaga Douji 烏倶婆か童子

- Shoujou Biku 清浄比丘

- Kongara douji 矜羯羅童子

- Seitaka douji 制た迦童子

In artistic representations Fudou is generally shown either alone or flanked by Kongara and Seitaka to create the Fudou Triad (fudou sanzon 不動三尊). There are few examples of him accompanied by all eight of these attendants. In artistic representations Fudou is generally shown either alone or flanked by Kongara and Seitaka to create the Fudou Triad (fudou sanzon 不動三尊). There are few examples of him accompanied by all eight of these attendants.

A fine set of wooden figures, six of which are attributed to Unkei 運慶 (?-1223), is preserved at Kongoubuji 金剛峯寺 (Mt. Kouya 高野, Wakayama prefecture). Another set, carved by Kouen 康円 in 1272, is housed at Kannonji 観音寺 in Tokyo.

Noteworthy examples of polychrome paintings of Fudou accompanied by these eight attendants include those kept by the Agency for Cultural Affairs (originally from Mt. Kouya; 13c) and at Choufukuji 長福寺 (Okayama prefecture; 14c). <end JAANUS quote>

|

Quoted from story by Catherine Ludvik in the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 33/1 (2006) entitled:

"In the Service of the Kaihogyo Practitioners of Mt. Hiei, The Stopping-Obstacles Confraternity (Sokusho ko) of Kyoto."

Pages 115-142

|

|

Kaihōgyō 回峰行 (かいほうぎょう) Kaihōgyō 回峰行 (かいほうぎょう)

1000 Day Circumambulation Devoted to Fudō Myōō

Known more fully as the Sennichi Kaihougyou (千日回峰行), or "one-thousand-day circumambulation." An arduous meditative practice of Tendai monks in which they walk around Mt. Hiei and its environs for one thousand days reciting the mantra of Fudo Myo-o, the central deity of the Kaihougyou. Mt. Hiei is home to the syncretic Tendai shrine-temple multiplex, located in Shiga Prefecture, near Kyoto. The term "HOU" in Kaihougyou refers to Mt. Hiei.

Writes scholar Catherine Ludvik, adjunct professor at the Stanford Japan Center in Kyoto: "The kaihougyou (kaihogyo) consists in walking around the sacred space of Mt. Hiei along a set course, stopping to worship at numerous sites along the way, including temple halls, shrines, graves, peaks, forests, trees, mounds, stones, waterfalls, ponds, and water sources, by forming mudras and reciting mantras.....to Fudo Myoo. The 1000-day practice is divided into one-hundred-day segments and can be completed over a period of seven years.

During the first three years, each year consisting of one hundred days of walking, the course extends over 7.5 ri 里 (1 ri = approx. 30 kilometers) and includes some 260 worship stops. During the next two years (4th & 5th years), two hundred days each, the same route is followed. During the sixth year, the course is extended to 15 ri over one hundred days. During the seventh year, it is extended further still to 21 ri over one hundred days, as the practitioner circumambulates both Mt. Hiei and Kyoto (Kyoto Oomawari 京都大廻り), followed by a final segment of one hundred days along the 7.5 ri route around the mountain."

Professor Ludvik says in the same article: "The kaihogyo is often called a ’walking meditation’ (hokou zen 歩行禅) and interpreted as a form of the constant-walking samadhi (jougyou zanmai 常行三昧), one of the four types of meditation (shishu zanmai 四種三昧) practiced in Tendai. In spirit, it is traced back to the Never Disparaging (Joufugyou 常不輕) Bodhisattva of the Lotus Sutra, who went about paying obeisance to monks and layment alike as future buddhas. In the kaihogyo, reverence is extended to all of nature, including every tree and blade of grass, for they too are endowed with Buddha nature. While those who complete this practice are believed to be living buddhas, the kaihogyo is in fact a bodhisattva practice, wherein the Gyouja (the practitioner 行者) stop short of attaining buddhahood in this life so as to continue to help all sentient beings."

Sokushō Kō 息障講 Sokushō Kō 息障講

Stopping-Obstacles Group

In her article, Ludvik discusses the probable origins of the "stopping-obstacles confraternity," an organization of individuals who devotedly serve the practitioner and act as guides through the Kyoto portion of the circumambulation. Writes Ludvik:

"The Sokushou-kou appears to derive its name from a temple in the western foothills of Mt. Hira in Shiga Prefecture known as Katsuragawa Sokushō Myō-ō-in 葛川息障明王院, an important center of Tendai mountain asceticism since the Heian period (794-1185). The temple was established by the founding figure of the Kaihougyou, the Tendai monk Souou 相応 (831-918), who performed ascetic practices in this area. When Fudo Myo-o appeared to him in a waterfall, Souou jumped in to embrace him, and, finding a log of a katsura 葛 tree, enshrined it. Tradition has it that from this log of katsura he carved three images of Fudo, worshipped today at Katsuragawa Sokushou Myou-ou-in, the temple he established near the waterfall, at Mudouji 無動寺, the temple he set up on Mt. Hiei, and at Isakiji 伊崎寺 in Shiga Prefecture." < end quotes from Catherine Ludvik in the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 33/1 (2006) >

Spellings Using Unicode Fonts

- Kaihōgyō 回峰行 -- abbrv. name for 1000-day-circumambulation

- Sennichi Kaihōgyō 千日回峰行 -- 1,000 day circumambulation

- Samādhi -- lit. intent contemplation, perfect absorption, the union of meditator with object of meditation

- Gyōja 行者 -- the practitioner

- Kyōto ōmawari 京都大廻り -- great circumambulation of Kyoto

- Jōgyō Zanmai 常行三昧 -- type of meditation practice

- Jōfugyō 常不輕 -- Never Disparaging Bodhisattva of Lotus Sutra

- Hokō zen 歩行禅 -- walking meditation

- Fudō Myō-ō -- the mantra king, wisdom king, wrathful emanation of Dainichi Nyorai

- Sokushō kō 息障講-- the stopping-obstacles confraternity

- Katsuragawa Sokushō Myōō-in 葛川息障明王院 -- name of temple in foothills of Mt. Hira

- Sōō 相応 -- Tendai monk who founded the Kaihōgyō

- Mudōji 無動寺 -- name of temple on Mt. Hiei

FUDO, WATERFALLS, & PILGRIMAGES

BELOW TEXT

Quote from NichirensCoffeeHouse (outside link). Myo-o, The Knowledge Kings, The Vidyarajas. These esoteric deities are the kings of mystic knowledge who represent the power of the Buddhas to vanquish blind craving. They are known as the the kings of mystic knowledge because they wield the mantras, which are the mystical spells made up of Sanskrit syllables imbued with the power to protect practitioners of the Dharma (Buddhist Law) from all harm and evil influences. The Vidyarajas appear in terrifying wrathful forms because they embody the indomitable energy of compassion which breaks down all obstacles to wisdom and liberation.

Quote from “Buddhism: The Flammarion Iconographic Guide”

by Louis Frederic (ISBN 2-08013-558-9)

Chiefly represented in Japan, Fudō Myō-ō, by his mystic name Joju Kongo, "the eternal and immutable diamond," is the chief of the five great kings of magic science.

SIDE NOTES: Some also say Fudō is the Hindu God “Shiva.” Flames in background said to represent the purification of the mind. In Kamakura (Japan), Fudō is enshrined at Jōju-in 成就院 and Myō-ō-in 明王院 (E-site here). Others say flame behind Fudō originated from the vomit of the mythical Karura.

Yakimochi Fudo. Yakimochi Fudō Son 焼き餅不動尊. Since 1783. During the great famine of Tenmei after the eruption of Mount Asama 天明の大飢饉 in 1782, the people of Takabayashi 高林 village on the river Ishisagawa 石田川 found a wooden statue of Fudō Myō-ō in the water and saved it. To celebrate, they used the last bits of small grains of rice and millet (awa, hie) for mochi dough and fried some leaves of daikon radish and other wild leaves for the filling. They presented these mochi to the deity and celebrate it to this day. The mochi are good for pregnant woman. The mothers of the village come to this shrine to celebrate on January and August 28, the memorial days of Fudō Myō-ō. <courtesy Gabi Greve>

LEARN MORE

- Buddhist-Artwork.com. Fudo statues are available for online purchase at our sister site.

- In Japan, many waterfalls are revered as a manifestation of Fudo. See Gabi Breve’s site for more details about Fudo’s manifestations in nature.

- JAANUS. Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System. Compiled by the late Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent; covers both Buddhist and Shinto deities in great detail and contains over 8,000 entries.

- A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms. With Sanskrit & English Equivalents. Plus Sanskrit-Pali Index. By William Edward Soothill & Lewis Hodous. Hardcover, 530 pages. Published by Munshirm Manoharlal. Reprinted March 31, 2005. ISBN 8121511453.

- Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙, the “Collected Illustrations of Buddhist Images.” Published in 1783 (Genroku 元禄 3). One of Japan’s first major studies of Buddhist iconography. Hundreds of pages and drawings, with deities classified into approximately 80 (eighty) categories. Modern-day reprints are available at this online store (J-site).

- Mandara Zuten 曼荼羅図典 (Japanese Edition). The Mandala Dictionary. 422 pages. First published in 1993. Publisher Daihorinkaku 大法輪閣. Language Japanese. ISBN-10: 480461102-9. Available at Amazon.

- Digital Dictionary of Chinese Buddhism (C. Muller; login "guest")

- The Phenomenon of Invoking Fudō for Pure Land Rebirth in Image and Text. By Karen Mack. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33/2: 297–317 © 2006. Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture.

- Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture. Numerous online scholarly papers and its semi-annual Japanese Journal of Religious Studies.

- A History of Japanese Religion. Edited by Kazuo Kasahara. Kosei Publishing Company, 2002. Translated by Paul McCarthy and Gaynor Sekimori. 648 pages. Sixteen distinguished experts on Japanese religion approach the topic from modern perspectives. Topics range from prehistoric times up until the early postwar years. Click here to read review of book by scholar Paul L. Swanson.

- Buddhism: Flammarion Iconographic Guides, by Louis Frederic, Printed in France, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. A highly illustrated volume, with special significance to those studying Japanese Buddhist iconography. Includes many of the myths and legends of mainland Asia as well, but its special strength is in its coverage of the Japanese tradition. Hundreds of accompanying images/photos, both B&W and color. A useful addition to your research bookshelf.

- See Bibliography for our complete list of resources on Japanese Buddhism, or visit any site page and scroll to the bottom for detailed resources on that specific deity or topic.

THIS IS A SIDE PAGE

RETURN TO MAIN MYŌ-Ō PAGE

Fudo Myo-o

Heian, Kyoto Nat’l Museum

|

|