|

|

|

|

|

COLOR RED IN JAPANESE MYTHOLOGY

|

|

Red bibs, robes, scarfs, and caps are related to certain deities.

Links to each deity page are provided in the story text.

|

|

Monkey

Expels Demons of Sickness

Deity of Fertility

|

Fox (Kitsune)

Oinari’s Messenger

Deity of Rice Harvest

|

Binzuru, Healer

Most Revered

Arhat in Japan

|

|

Koyasu Kannon

Goddess of Mercy

“Child-Giving” Kannon

|

Koyasu Jizō

Protector of Children

“Child-Giving” Jizō

|

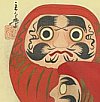

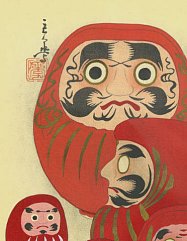

Daruma

Good Luck Doll &

Protector from Illness

|

|

Shishi Lion-Dog

Guards shrine gate

|

Niō Kings

Guards temple gate

|

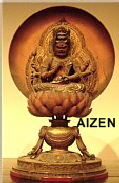

OTHER RED THEMES

Yakudoshi (Bad Luck Years)

Kanreki (60th Birthday)

Fudō & Aizen (Wrtahful Deities)

Akadōji (Red Youth)

Shitennō (Four Guardians)

Maneki Neko (Beckoning Cat)

Aka-Beko (Red Ox)

Monkey and Smallpox

|

|

|

|

Smallpox Demons

Ukiyo-e print by Yoshitoshi, c. 1890

(Detail from woodblock)

Courtesy of the Naito Museum of

Pharmaceutical Science & Industry

Hashima, Gifu, Japan. Photo here

|

|

DEMONS AND DISEASE. In Japan, the color red is associated closely with a few deities in Shinto and Buddhist traditions, and statues of these deities are often decked in red clothing or painted red. There are many clues that underpin the red association. The most compelling clues involve demon quelling and disease (e.g., smallpox, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, measles). According to Japanese folk belief, RED is the color for "expelling demons and illness.” The rituals of spirit quelling were regularly undertaken by the Yamato court during the Asuka Period (522 - 645 AD). Centered on the fire god (a red deity), these purification rites were designed to purify the land by sending evil spirits to the Ne no Kuni (details here). This association with evil segues easily into other links with child mortality, protection against evil forces (sickness), fertility, the caul (embryonic membrane covering the head at birth), and other child-birth imagery. The red bibs, red robes, red scarfs, and red caps found frequently on certain Japanese deities (discussed below) lend strong support to this interpretation. DEMONS AND DISEASE. In Japan, the color red is associated closely with a few deities in Shinto and Buddhist traditions, and statues of these deities are often decked in red clothing or painted red. There are many clues that underpin the red association. The most compelling clues involve demon quelling and disease (e.g., smallpox, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, measles). According to Japanese folk belief, RED is the color for "expelling demons and illness.” The rituals of spirit quelling were regularly undertaken by the Yamato court during the Asuka Period (522 - 645 AD). Centered on the fire god (a red deity), these purification rites were designed to purify the land by sending evil spirits to the Ne no Kuni (details here). This association with evil segues easily into other links with child mortality, protection against evil forces (sickness), fertility, the caul (embryonic membrane covering the head at birth), and other child-birth imagery. The red bibs, red robes, red scarfs, and red caps found frequently on certain Japanese deities (discussed below) lend strong support to this interpretation.

Briefly, the Japanese god of smallpox -- Hōsō Kami 疱瘡神 -- is intimately associated with the color red in Japan. The first record of smallpox in Japan appears in the Nikon Shoki (日本書紀, approx. 720 AD). But the disease reached Japan much earlier, around the time of Buddhism’s introduction (circa 550 AD). The disease was very dangerous. If the ill person’s skin turned purple, it was considered serious. But if the skin turned red, it was believed the patient would recover.

This early association between demons of disease and the color red was gradually turned upside-down -- proper worship of the disease deity would bring life, but improper worship or neglect would result in death. In later centuries, the Japanese recommended that children with smallpox be clothed in red garments and that those caring for the sick also wear red (smallpox details here). The Red-Equals-Sickness symbolism quickly gave way to a new dualism between evil and good, between death and life, between hell and heaven, with red embodying both life-creating and life-sustaining powers. As a result, the color red was dedicated not only to deities of sickness and demon quelling, but also to deities of healing, fertility, and childbirth. Many countries outside Japan also have “red” traditions that are closely associated with sickness. See this outside site for details.

THE MONKEY THE MONKEY

The Japanese word for monkey (猿 saru) is a homonym for the Japanese word expel (去る), the latter meaning to “dispel, punch out, push away, beat away," and thus monkeys are thought to dispel evil spirits. At Shinto shrines, red-colored monkey charms are used in Japan, even today, to ward off demons, evil spirits, and sickness (see Migawari-zuri below).The buildings at some Hie Shrines in Japan use monkey carvings to hold up the beams (see Munamochi-saru photo at right). These pillar monkeys also reflect the simian’s early role as protector against evil. Moreover, the monkeys worshipped at many Hie Jinja shrines in modern Japan are considered patrons of fertility, safe childbirth, and harmonious marriage. At these shrines, the monkey statues are often decked in red clothing, the color meant to symbolize fertility and childbirth. Women can even buy red underpants called Saru-mata 猿股 (lit. monkey underwear), which equates to the red buttocks of female monkeys in heat, and thus symbolizes fertility. For many more details on the monkey and monkey mythology in Japan, please see the Monkey Pages.

MIGAWARI-ZARU 身代わり猿. Literally "substitution monkey." This red monkey charm is hung on the eves of the house to protect the inhabitants from sickness, disaster, and to block evil from entering the home. One doll for each person of the home is hung on the eve of the house. Said to protect sinners from punishment by Kōshin, as the monkey (Kōshin’s messenger) is punished instead. Hence the name Migawari-zaru -- the substitution monkey. Still a practice found in the old part of Nara city (details here).

NEGAI-ZARU 願い猿, literally “wish monkey.” Another name for the Migawari-zaru monkey charm mentioned above. People write their wishes on the back of this monkey charm, hang it up, and hope their wishes will be granted by the monkey deity.

SANNŌ GONGEN 山王権現

Japan’s approximately 3,800 Hie Jinja shrines are dedicated to the diety Sannō and to Sannō Gongen (lit. = mountain king avatar). SANNŌ is the central deity of Japan’s Tendai Shinto-Buddhist multiplex on Mt. Hiei (Shiga Prefecture, near Kyoto). Sannō Gongen is Sannō’s messenger (tsukai 使い) and avatar (gongen 権現), and is portrayed as a monkey. At these shires, the monkeys -- both male and female -- are considered the patrons of harmonious marriage and safe childbirth. Please see Monkey (Page Three) for details.

Above two photos courtesy of James Baquet

Female with babe and male monkey guard the gates

at Hie Jinja (Hie Shrine), Akasaka, Tokyo, Japan

THE FOX

|

Kitsune (Oinari’s Messenger)

Fox at Tsurugaoka Hachimangu

Shrine in Kamakura City

|

|

In the Shinto realm, the fox deity known as KITSUNE is often decked in red bibs. The fox is the messenger of Oinari, the deity of food, farmers, and the rice harvest. Oinari (also written Inari) appears in both male and female form, and is generally associated with various manifestations of the Hindu goddess Dakini, who in turn is associated with Daikoku-ten (Mahakala), the latter considered the Hindu god of Five Cereals and one of Japan’s Seven Lucky Gods. In the Shinto realm, the fox deity known as KITSUNE is often decked in red bibs. The fox is the messenger of Oinari, the deity of food, farmers, and the rice harvest. Oinari (also written Inari) appears in both male and female form, and is generally associated with various manifestations of the Hindu goddess Dakini, who in turn is associated with Daikoku-ten (Mahakala), the latter considered the Hindu god of Five Cereals and one of Japan’s Seven Lucky Gods.

Here the symbolism is two-fold. First, rice is sacred in Japan, closely associated with fertility (the pregnant earth) and with sustaining life. Foxes must therefore be placated -- otherwise it would be disastrous to the livelihood of the nation’s farmers and people. Second, the fox is associated with the concept of Kimon 鬼門 (a Japanese term stemming from Chinese geomancy; literally “demon gate”). Kimon generally means ominous direction, or taboo direction, and can be most accurately translated as "demon gate to the northeast," or the "northeast place where demons gather and enter." The fox, like the monkey, is able to ward off evil kimon, and therefore the fox, in Japan, plays the same role as the monkey in guarding the demon gate to the northeast.

For the monkey, this is easy to understand. The Japanese word for monkey (猿 saru) is a homonym for the Japanese word 去る, which means to “dispel, punch out, push away, beat away," and thus monkeys are thought to dispel evil spirits. But there is no similar reason (that I know of) for the fox’s ability to ward off evil. There are approximately 20,000 Inari (fox) shrines nationwide. Characteristics of Inari shrines are red torii (gates) protected by a pair of fox statues, one on the left and one on the right. Chinese concepts of geomancy (i.e., feng shui) are discussed here.

Shishi Gate Guardians. The entrance gates to temples and shrines are most often guarded by a pair of protector deities. At Hie Jinja Shrines, the gates are guarded by monkey deities. At Oinari Shrines, the gates are guarded by a pair of foxes. The majority of shrines, however, are guarded by a pair of Shishi lion-dogs, while most temples are guarded by the two Niō Kings. There are exceptions, mind you, as some temples are protected by shishi lion-dogs. In many cases, these gate protectors are garbed in red or painted red, for their job is to block the path to evil (and RED, as we have discovered, is the color used to expel demons and illness).

Shishi Gate Guardians at shrine in Youanji Oami.

See the Shishi page for many more details.

Niō Gate Protectors at Sugimoto-dera, Kamakura

See the Niō page for many more details.

SPECULATIVE

Shinto Gates are typically red in color. I’m not exactly sure why, but it may relate to

the “expelling of demons,” i.e., to blocking evil from entering the Shinto precincts.

BINZURU

In Japan’s Buddhist realm, three deities in particular are associated with the color red. Bindorabaradaja 賓度羅跋羅惰闍 (also called Binzuru) is the most widely revered of the Arhat in Japan. Statues of Binzuru, in painted wood or stone, are usually well worn, since the faithful follow the custom of rubbing a part of the effigy corresponding to the sick parts of their bodies, as he is reputed to have the gift of healing. He is also frequently offered red and white bibs and children's caps to watch over the health of babies, so that his statue is often decked in rags. The red cap on his head probably symbolizes the placenta or the caul (the embryonic membrane covering the head at birth), and/or the magical powers of healing, as a red scarf was customarily placed on the head of sick individuals in Japan to pray for their speedy recovery. This cap is also found on effigies of Jizō Bosatsu and Kannon Bosatsu. In Japan’s Buddhist realm, three deities in particular are associated with the color red. Bindorabaradaja 賓度羅跋羅惰闍 (also called Binzuru) is the most widely revered of the Arhat in Japan. Statues of Binzuru, in painted wood or stone, are usually well worn, since the faithful follow the custom of rubbing a part of the effigy corresponding to the sick parts of their bodies, as he is reputed to have the gift of healing. He is also frequently offered red and white bibs and children's caps to watch over the health of babies, so that his statue is often decked in rags. The red cap on his head probably symbolizes the placenta or the caul (the embryonic membrane covering the head at birth), and/or the magical powers of healing, as a red scarf was customarily placed on the head of sick individuals in Japan to pray for their speedy recovery. This cap is also found on effigies of Jizō Bosatsu and Kannon Bosatsu.

JIZŌ BOSATSU

|

Jizō Bosatsu

Savior from Torments

of Hell, and Patron of

Children and Motherhood

|

|

One of Japan’s most beloved deities, Jizō is the guardian of travelers, the hell realm, children, and motherhood. Everywhere in Japan, at busy intersections, at roadsides, in graveyards, in temples, and along hiking trails, one will find statues of Jizō Bosatsu decked in clothing, wearing a red or white cap and bib, adorned with toys, protected by scarfs, or piled high with stones offered by sorrowing parents. Such symbolism is based on numerous early influences, which are presented below: One of Japan’s most beloved deities, Jizō is the guardian of travelers, the hell realm, children, and motherhood. Everywhere in Japan, at busy intersections, at roadsides, in graveyards, in temples, and along hiking trails, one will find statues of Jizō Bosatsu decked in clothing, wearing a red or white cap and bib, adorned with toys, protected by scarfs, or piled high with stones offered by sorrowing parents. Such symbolism is based on numerous early influences, which are presented below:

- According to Japanese folk belief, red is the color for expelling demons and illness. Rituals of spirit quelling were regularly undertaken by the Japanese court during the Asuka Period (522 - 645 AD) and centered on a red-colored fire deity. This early association between demons of disease and the color red was gradually turned upside-down -- proper worship of the disease deity would bring life, but improper worship or neglect would result in death. In later centuries, the Japanese recommended that children with smallpox be clothed in red garments and that those caring for the sick also wear red. The Red-Equals-Sickness symbolism quickly gave way to a new dualism between evil and good, with red embodying both life-destroying and life-creating powers. As a result, the color red was dedicated not only to deities of sickness and demon quelling, but also to deities of healing, fertility, and childbirth. Jizō’s traditional roles are to save us from the torments/demons of hell, to bring fertility, to protect children, and to grant longevity -- thus Jizō is often decked in red.

- The tradition of dressing certain Buddhist and Shintō deities in red bibs first reportedly appeared in the Heian era and examples can be found in illustrated handscrolls (emakimono 絵巻物) and in the classic Tale of Genji 源氏物語. Note: I have not yet confirmed these findings.

- Perhaps the greatest influence on Japan’s tradition of decking Jizō statues in hats, bibs, scarfs, and toys comes from the Sai no Kawara legend attributed to Japan’s Pure Land sects in the 14th and 15th centuries. According to this legend, children who die prematurely are sent to the underworld for judgment -- like all sentient beings, their life is reviewed by the 10 Kings of Hell, judgment is pronounced, and they are reborn into one of six realms of existence. They may be pure souls, but they have not had any chance to build up good karma, and their untimely death caused great sorrow to their parents, and thus, they too, must undergo judgment. They are sent to Sai no Kawara, the riverbed of souls in purgatory, where they are forced to remove their clothes and to pray for salvation by building small stone towers, piling pebble upon pebble, in the hopes of climbing out of limbo into Buddha’s paradise. But hell demons, answering to the command of the old hell hag Shozuka no Baba (also called Datsueba), soon arrive and scatter their stones and beat them with iron clubs. But no need to worry, for Jizō comes to the rescue, often hiding them in the sleeves of his robe. Even today, this horrific folklore about hell prompts Japanese parents into action. Says Kondo Takahiro (an independent Buddhist scholar from Yokohama): “They imagine their little babies lingering at the riverbed, unable to cross the river, unable to gain salvation. Japanese parents therefore feel a great need to do something to alleviate their child’s suffering, to do something to improve the child’s chance of redemption. Thus the great cult of Jizō Bosatsu in Japan. Parents cloth Jizō statues in hopes that Jizō will cloth the dead child in his protection. Small pebbles are piled around the Jizō statue as well, offered by sorrowing parents as a prayer to Jizō to help the suffering soul of their deceased child. Even today, Jizō statues in some places in Japan are covered -- sometimes from top to bottom -- in pebbles placed there by sorrowing parents, who believe that every stone tower they build on earth will help the soul of their dead child in performing his/her penance.”

- In the Muromachi period, images of the Life-Prolonging Jizō (Enmei Jizō 延命地蔵) began appearing along with two youthful acolytes-servants known as Shōzen 掌善 (white in color, holding a white lotus, master of good, standing to the left of Jizō), and Shōaku 掌悪 (red in color, holding a vajra club, master of evil, standing to the right of Jizō). These two are seldom represented in artwork, but rather symbolized by white and red cloth attached to many Jizō statues. This Pure-Land symbolism obviously borrowed from similar iconography associated with the esoteric Shingon deity Fudō Myō-ō, who is often accompanied by two youthful acolytes-servants known as the white-skinned Kongara Dōji 矜羯羅童子 (who personifies obedience) and the red-colored Seitaka Dōji 制姙迦童子 (who personifies expedient action). Such iconography was probably of Chinese Taoist origin, but it was subsequently incorporated into Buddhism. The Pure Land sects, for example, believe in two deities of Chinese Taoist providence called Kushōjin 倶生神. These two assist the 10 Kings of Hell during the judgment of deceased souls. The pair reportedly keep a complete record of our behavior from the time of our birth to the time of our death, with one recording only our good behavior and the other only the bad.

- In modern Japan, a red hat, bib, and toys are still often found on Jizō statues, the gifts of a rejoicing parent whose child has been cured of dangerous sickness thanks to Jizō's intervention, or a gift to help the deceased child in the afterlife. These traditional practices are now combined with Japan’s modern Mizuko Jizō practices (wherein bereaved parents buy tiny Jizō statues to pray for the soul of their aborted or miscarried children). Adds independent scholar Kondo Takahiro: “Some temples, without doubt, take advantage of this folklore. They tell the traumatized parents ‘Your lost child will continue to suffer. Your lost child will never be saved unless you take action to soothe their troubled souls. You must buy statuettes and offer religious services to alleviate their suffering.‘ In Japan, the Buddhist tendency toward mercy and prolonged mourning means that many grieving parents buy expensive statuettes and pay exorbitant fees for memorial services -- the temples thus prosper from such patronage.“

- In modern Japan, a red hat, bib and toys are often found on Jizō statues, the gifts of a rejoicing parent whose child has been cured of dangerous sickness thanks to Jizō's intervention, or a gift to help the deceased child in the afterlife.

KANNON BOSATSU

The God / Goddess of Mercy, is one of the most widely worshiped divinities in Japan and mainland Asia. Kannon Bosatsu can appear in many different forms to save people according to their time and place. In Japan, the forms most closely related to children and motherhood (and hence the color red) are Koyasu Kannon 子安観音 (safe childbirth) and Mizuko Kuyō Kannon 水子供養観音 (patron of departed souls, especially children lost to miscarriage, stillbirth, or abortion). Statues of these two are often decked in red by parents who are praying for a child, or by parents who are praying for the repose of their dead child. The God / Goddess of Mercy, is one of the most widely worshiped divinities in Japan and mainland Asia. Kannon Bosatsu can appear in many different forms to save people according to their time and place. In Japan, the forms most closely related to children and motherhood (and hence the color red) are Koyasu Kannon 子安観音 (safe childbirth) and Mizuko Kuyō Kannon 水子供養観音 (patron of departed souls, especially children lost to miscarriage, stillbirth, or abortion). Statues of these two are often decked in red by parents who are praying for a child, or by parents who are praying for the repose of their dead child.

Kannon’s Koyasu form incorporates the iconography of the Shinto goddess Koyasu-sama. Legend says this Shinto kami gave birth to a healthy son while her house was devoured by flames -- thus her role as the kami who grants safe childbirth. Statues of Koyasu Kannon are often decked in red by couples praying for a child. It was probably only from the 14th century AD, perhaps under the influence of the Nichiren sect, that people began worshipping Koyasu Kannon as "giver of children."

DARUMA

|

Monkey holding red Daruma doll.

Double Good Luck, Circa 1960.

Courtesy eBay

Good Luck Daruma Dolls

Photo courtesy Gabi Greve

|

|

The father of Zen Buddhism. Daruma comes in many forms in Japan. The form most related to getting pregnant and easy childbirth is called 子持ち、安産のだるま. Artwork of Daruma often shows him wearing a red robe, while the popular good-luck Daruma dolls (often with a threatening face) are nearly always red in color, for red is believed to ward off disease. Daruma is thus widely recognized in Japan as the preventer and healer of sickness. The father of Zen Buddhism. Daruma comes in many forms in Japan. The form most related to getting pregnant and easy childbirth is called 子持ち、安産のだるま. Artwork of Daruma often shows him wearing a red robe, while the popular good-luck Daruma dolls (often with a threatening face) are nearly always red in color, for red is believed to ward off disease. Daruma is thus widely recognized in Japan as the preventer and healer of sickness.

Says scholar Bernard Faure (Stanford University): “Japanese stories, studied in detail by Hartmut Rotermund, show that, by the beginning of the Edo period, Daruma had become a protector against smallpox, and his role consisted in watching the smallpox demons so that they would not harm children. Daruma dolls were usually offered with other auspicious toys to sick children. We must note in this context the importance of the color red (which symbolizes, among other things, measles). The altar to the smallpox god was decorated with red paper strips (gohei), a Daruma doll, and an owl; sometimes a doll called shōjō (orang-outan) was included. Also, the sick child had to wear a red hood. “Treatment by the Red” (Jp: kōryōhō) is found in Europe as well. The god of smallpox is said to like the red color, so one tries to please him in the hope of being cured quickly. To the “epidemic” affinities suggested by the redness of the complexion or of the robe, one could add others, less epidermic, like the elusive relations of Daruma with monkeys in general, and perhaps also with the simian Sarutahiko.

For somewhat obscure reasons, Daruma is said to be a protector of horses and monkeys (see Monkey, Protector of Stables). A rather unusual motif is that of his relation with the “Prince of the Stable” (umayado), that is, Imperial Prince Shōtoku Taishi (574 - 622 AD), whose legend has him born in a stable. On that occasion, Bodhidharma (Daruma) is said to have reincarnated himself as a horse, which neighed three times. This may still have to do with the notion of Daruma as a “placenta deity.” <end abridge quote from Bernard Faure>

OTHER RED TRADITIONS IN JAPAN

OTHER BUDDHIST DEITIES & RED

Yakudoshi 厄年 -- Years of Bad Luck

Text Japanese Cultural Center, Hawaii Text Japanese Cultural Center, Hawaii

Bad luck ages are referred to as yakudoshi, with yaku meaning “calamity” and doshi signifying “year(s).” These years are considered dangerous because they are believed to bring bad luck or disaster. For men, the ages 25 and 42 (24 and 41 in China) are deemed critical years, with 42 being especially critical. It is customary in these unlucky years to visit temples and shrines to provide divine protection from harm. The birthday person should wear red to bring good health, vitality and long life. The equivalent yakudoshi ages for women are 18 and 33 (18 and 32 in China), with 33 thought to be a particularly hard, terrible or disastrous year. Like the age 42 for men, precautions are taken to ward off bad luck. <Editor’s Note: Many Japanese shrines also sell paper balloons and pictured kites to people in their yakudoshi years. After buying the talisman, these people chase away bad luck by burning or “blowing up” the paper balloons and kites.>

Kanreki 還暦, 60th Birthday Celebration

Text Japanese Cultural Center, Hawaii Text Japanese Cultural Center, Hawaii

For men, the 60th birthday is called kanreki, the recognition of his “second infancy.” The Japanese characters in the word kanreki literally mean “return” and “calendar.” The traditional calendar, which was based on the Chinese Zodiac calendar, was organized on 60-year cycles. The cycle of life returns to its starting point in 60 years, and as such, kanreki celebrates that point in a man’s life when his personal calendar has returned to the calendar sign under which he was born.

Traditionally, friends and relatives are invited for a celebratory feast on one’s 60th birthday. It is customary for the celebrant to be given a red hood and wear a red vest. These clothes are usually worn by babies and thus symbolize the celebrant’s return to his birth. <end quote Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii>

MYŌ-Ō 明王. The Myō-ō (Myo-o) are warlike emanations who represent the luminescent wisdom of the Buddha, and guard the four cardinal directions and the center. Fudō is the best known of the Myō-ō deities, and one of the main deities of the Shingon sect of Esoteric Buddhism. He is often painted red. The red flames of Fudō’s aureole are said to represent the purification of the mind. Fudō converts anger into salvation; has furious, glaring face, as he seeks to frighten people into accepting the teachings of Dainichi Nyorai; carries "kurikara" or devil-subduing sword in right hand (also represents wisdom cutting through ignorance); holds rope in left hand (to catch and bind up demons); often has third eye in forehead (all-seeing); often seated or standing on rock (because Fudō is "immovable" in his faith). Aizen is another popular Myō-ō. The God of Love, and King of Sexual Passion, Aizen converts earthly desires into spiritual awakening. Often depicted with a red body, symbolizing the power to purify sexual desire. MYŌ-Ō 明王. The Myō-ō (Myo-o) are warlike emanations who represent the luminescent wisdom of the Buddha, and guard the four cardinal directions and the center. Fudō is the best known of the Myō-ō deities, and one of the main deities of the Shingon sect of Esoteric Buddhism. He is often painted red. The red flames of Fudō’s aureole are said to represent the purification of the mind. Fudō converts anger into salvation; has furious, glaring face, as he seeks to frighten people into accepting the teachings of Dainichi Nyorai; carries "kurikara" or devil-subduing sword in right hand (also represents wisdom cutting through ignorance); holds rope in left hand (to catch and bind up demons); often has third eye in forehead (all-seeing); often seated or standing on rock (because Fudō is "immovable" in his faith). Aizen is another popular Myō-ō. The God of Love, and King of Sexual Passion, Aizen converts earthly desires into spiritual awakening. Often depicted with a red body, symbolizing the power to purify sexual desire.

RED YOUTH AKADŌJI 赤童子

|

Kasuga Akadōji

Painting, Dated 1488

H = 73.9 cm, W = 31.5 cm

Treasure of Uetsuki Hachiman Jinja 植槻八幡神社 (in Nara).

|

|

Text courtesy JAANUS. Text courtesy JAANUS.

Literally “Red Youth.” Also often called Kasuga Akadōji 春日赤童子. A mysterious human figure said to have appeared on a rock immediately in front of the Kasuga 春日 Shrine gate. He often is shown as a youth (Jp. = dōji), colored red (Jp = aka), standing on a rock, and leaning on a staff. In certain poses both in paintings and in prints, Akadōji resembles Kongōdōji 金剛童子, one of the attendants of Fudō Myō-ō 不動明王.

His connection with Kasuga is obscure, but he has been identified with Ame-no-Koyane 天児屋根, the Shinto god of the Third Sanctuary there; with Jinushi gami 地主神, the Shinto land god; with a healer's helping spirit; and with a thunder god of Mount Mikasa 御蓋, which stands behind the shrine at Kasuga. Extant images date from the Muromachi to Edo periods. < Photo courtesy of this J-site. >

SHITENNŌ

Guardians of the Four Compass Directions Guardians of the Four Compass Directions

Hindu deities incorporated into Buddhism. Among the four, two in particular are associated with the color red. In Japan, Kōmokuten is most often shown carrying a writing brush and scroll, but in mainland Asia, he is often shown with red skin holding a jewel in one hand and a snake in the other or coiled around him. Kōmokuten is attended by the nagas (serpents, including the dragon) and the Putanas (type of hungry ghost associated with fevers and protecting pregnant women).

Also see Zōchoten, one of the four, who symbolizes south, summer, red, and fire. He is attended by the Kumbhandas (spirit-sucking demons who drain the vitality of people, said in some texts to have human form but with the head of a horse, or said to be demons shaped like gourds, or to have scrotums shaped like gourds, or to have large scrotums).

MANEKI NEKO

Literally "beckoning cat." Literally "beckoning cat."

One of the most common lucky charms in Japan. Found frequently in shop windows, the Maneki Neko sits with its paw raised and bent, beckoning customers to enter. It is commonly believed that the Maneki Neko became popular in the latter half of the Edo Period (1603 - 1867 AD), although this lucky cat is rarely mentioned by name in era documents. By the Meiji Period (1868 - 1912), however, it appears with great regularity in publications and business establishments. Statues of this cat come in a wide variety of colors. Various sites devoted to this lucky charm (see Maneki Neko page) claim that the less-prevalent red-colored Maneki Neko is used to exorcise evil spirits and to combat illness. Also, the red collar (with bell) found on most Maneki Neko probably originated from a custom of the Edo Period. During those days, affluent ladies adorned their cats with red collars made of hichirimen (Camellia Japonica, a red flower), and small bells were attached to the collar to help the owners keep track of their pets.

AKA-BEKO (RED OX)

Red in Japan (Dr. Gabi Greve) Red in Japan (Dr. Gabi Greve)

Photo courtesy Bandcantiques.com and text as presented on Dr. Gabi Greve’s site. “This whimsical lacquered red papier-mache figure of an ox is known as an “aka-beko” which, literally translated, means red calf. Mid-20th Century. Her head, which is attached by a string, nods up and down and from side to side. This little folk toy comes from Fukushima Prefecture in the Tohoku region of Japan. Some 350 years ago, the townspeople constructed a large temple there dedicated to Buddha. Heavy loads of lumber had to be transported long distances, and one of the oxen used was a large reddish cow. When the temple was completed, the cow refused to leave the site. Shortly thereafter a member of the ruling clan fashioned a small effigy of the devout cow as a child’s toy. Made of lacquered papier-mache, the free swinging head bobs easily with any movement and delights children of all ages. When a great plague of smallpox swept the country, people appealed to Buddha for deliverance. It was noticed that children who had this toy were not afflicted with the dread disease, and the superstitious local populace began to make similar toys as amulets against illness. (See “Mingei” by Amaury Saint-Gilles.) Aka-beko are looked upon as omens of good luck and prosperity and are given as gifts at New Year’s and other auspicious occasions.” < End Quote Dr. Gabi’s site >

Japanese Web Sites on AKA-BEKO (from Dr. Gabi)

NANDI (Sanskrit)

|

Cow Deity at Mt. Hiei.

Nandi (Sanskrit) is a vehicle and

alter ego of the Hindu God Shiva.

Photo Courtesy: Miriam Solon at the

Buddhist Temple of Chicago.

The red bib on this statue is

suggestive of "illness repelling"

or "demon quelling."

|

|

Sacred Ox / Cow / Water Buffalo Sacred Ox / Cow / Water Buffalo

Says site contributor Dr. Gabi Greve: "This is NANDI, the vehicle and alter ego of Shiva. Statues of this animal are found in temples where Fudō Myō-ō is venerated, and also where Daijizaiten is venerated. Daijizaiten is often shown seated on a dark-blue buffalo in the Womb World Mandala. It is mostly a symbol / icon of Esoteric Buddhism in Japan (Shingon, Tendai).”

For more details, see this page by Gabi. Also see another page by Gabi that discusses the Ox-Headed Kannon and Ox-Headed Gozu Myō-ō 牛頭明王. There may be some connection between Nandi and the Ox-Headed Gozu Tennō 牛頭天王 (another outside site).

In Japan, the cow is a symbol of enlightenment. Various deities are shown riding atop it, including Daijizaiten and Daiitoku Myō-ō.

|

MONKEY AND SMALLPOX

Quoted from story by Bernard Faure Quoted from story by Bernard Faure

Professor of Asian Religions, Stanford University.

Monkeys were apparently used in some rites against smallpox. They were perceived as the messengers of the god Shoozenshin, a deity of Indian origin whose rite was allegedly transmitted to Japan by Bodhidharma (Daruma). It is worth noting that the names of this god recalls that of Jūzenji, a Mt. Hiei deity who also had monkeys as emissaries. In rites against smallpox, one made a monkey dance (saru-mawashi) to determine whether the illness would be light or not. According to the Sarumawashi no Ki: “The main deity [honzon] of the sarumawashi is the first patriarch {Bodhidharma, Daruma}, and its protecting deity is Sarutahiko.” The apotropaic function of this rite is underscored by the Saruya Denki, which mentions a legend according to which Sarutahiko made monkeys dance in order to rout a demon army. <End quote by B. Faure. Click here to read the entire story.>

HŌSŌ (HOSO, HOUSOU) KAMI -- GOD OF SMALLPOX IN JAPAN

Below text courtesy of Centers for Disease Control

www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol8no7/v8n7cover.htm

www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol6no6/cover.htm

From Hartmut O. Rotermund (Hōsōgami ou la petite ve' role aise' ment, Paris, Maisonneuve Larose, 1991). The first record of smallpox in Japan was found in the Nihon Shoki, published in 735 (the 7th year of Tempyo). The incident was also described in Ishinho, the oldest medical book in Japan, issued by Yasuyori Tanba in 984 (the 2nd year of Eikan). Smallpox, called Hōsōgami 疱瘡神 or Hōsōkami in Japanese, came to Japan in the same era as Buddhism. The disease was considered very dangerous. Even those who recovered could have pockmarks or loss of sight. Parents were constantly concerned about their children becoming ill with smallpox. The color red was used in prints and other smallpox illustrations because it was believed that Hōsō-gami, the god of smallpox, felt strongly about this color. When the skin rash was purple, the patient’s condition was considered serious. If the rash turned red, the patient would recover safely. Shoni-Hitsuyo-Yoikugusa, written by Gyuzan Kazuki in 1798 (the 10th year of Kansei), recommended that children with smallpox be clothed in red garments and that those caring for the sick also wear red. "Hōsō-e" color prints against smallpox (also known as Aka-e 赤絵, lit. "red prints") were used in prayers to boost the morale of ill children. After the patients recovered, these pictures were burned or floated down the river. Therefore, few examples are left of prints in which the color red predominates. The pictures drawn as protection against smallpox depicted heroic figures to give people courage against smallpox. Tametomo, a heroic samurai, was a representative genie. Legend has it that Tametomo was once banished to Hachijyo Jima, a small island far from main island in Japan, and that is why smallpox never occurred there. <end quote> Editor’s Note. Red-colored prints to ward off smallpox also commonly featured Daruma and an Owl. See Daruma above. For many more photos of red-colored Daruma prints, see the Daruma page.

Tametomo no bui toukigami wo shirizoku zu

Ukiyo-e woodcut print by Yoshitoshi, c. 1890

Naito Museum of Pharmaceutical Science & Industry

Hashima, Gifu, Japan. Photo found at this web site.

GODDESSES OF SMALLPOX IN INDIA

Quoted from www.indianchild.com/hindu_goddesses.htm

The goddess of smallpox, known as Shitala in North India and Mariamman in South India, remains a feared and worshiped figure even after the official elimination of the disease, for she is still capable of afflicting people with a number of fevers and poxes. Many more localized forms of goddesses, known by different names in different regions, are the focus for prayers and vows that lead worshipers to undertake acts of austerity and pilgrimages in return for favors. <end quote>

NOTEBOOK: NOTES ON UNFINISHED RESEARCH

- Mt. Kataoka (in Nara Prefecture)

Daruma, Smallpox and the Color Red

The Double Life of a Patriarch

A wonderful article by Professor Bernard Faure, Stanford Univ.

At the intersection of roads connecting Naniwa with the Asuka region, where the court was located at the time (Asuka Period, 522 - 645 AD), Kataoka was an important ritual space. Kataoka was a site where the ritual of spirit quelling was regularly undertaken by the Yamato court. These purification rites, centered upon the fire god (a red deity), were designed to purify the land by sending evil spirits to the Ne no kuni. They involved the use of ritual dolls (hitogata), substitute bodies that were dressed in the ruler’s clothes before being sent off, like scapegoats, bearers of collective defilement. This cult calls to mind that of the “back door” (ushirodo) of Japanese Buddhist temples, dedicated to Matarajin or similar deities, protectors with a dubious past or an ambivalent nature. The image of Daruma is usually located on the left (the northwest), Daigenshuri on the right (on the northeast) -- two directions associated with the gate of demons 鬼門 (kimon).

- Story of Kannon Bosatsu, The Offering of a Red Scarf

from Dreams, Myths & Fairy Tales in Japan, Einsiedeln, Switzerland, Daimon, 1995.

Courtesy of www.cgjungpage.org/index.php

In this story, the appearance of the red skirt on Kannon's statue is a sign of her having traversed this world from the "other" to help those in need. From Dreams, Myths & Fairy Tales in Japan, 1995. See Hayao Kawai's chapter on "Interpenetration: Dreams in Medieval Japan." Kawai recounts the following medieval story:

There was a man living with his wife and only daughter. He loved his daughter very much and made several attempts to arrange a good marriage for her, but was unable to succeed. Hoping for better fortune, he built a temple in his backyard, enshrined it with the bodhisattva of compassion, Kannon, and asked the deity to help his daughter. He died one day, followed by his wife shortly thereafter, and the daughter was left to herself. Though her parents had been wealthy she gradually became poor and eventually even the servants left. Utterly alone, she had a dream one night in which an old priest emerged from the temple of Kannon in the backyard and said to her, "Because I love you so much, I would like to arrange a marriage for you. A man I have called will visit here tomorrow. You should do whatever he asks."

The next night a man with about thirty retainers came to her home. He seemed quite kind and proposed to marry her. He was attracted to her because she reminded him of his deceased wife. Remembering the words which Kannon had spoken to her in her dream, she accepted his proposal. The man was very pleased and told her that he would be back the next day after attending to some business.

More than twenty of his retainers remained behind to spend the night at her home. She wanted to be a good hostess and prepare a meal for them, but she was too poor to do so. Just then an unknown woman appeared who identified herself as the daughter of a servant who used to work for the parents of the hostess a long time ago. Sympathetic to the hostess' plight, she told the latter that she would bring food from her home to feed the guests. When the man returned the next day, she helped the daughter of her parents' master again by serving the man and his attendants. The hostess showed her gratitude by giving her helper a red ceremonial skirt (Jpn. hakama).

When the time came to depart with her fiancee, she went to the temple of Kannon to express her thanks. To her surprise she found the red skirt on the shoulder of the statue; she realized then that the woman who had come to help her was actually a manifestation of Kannon.

We see in this story not only the realization of what was promised in a dream, but also the Kannon's entry into this life as the former servant's daughter. Added to that is the appearance of the red skirt on the Kannon's statue as a sign of her having traversed this world from the "other."

Puzzling over Malta Kano's ever-present red vinyl hat, I recalled the many small, stone statues of a seated figure with a red cloth shawl or bib and turban (sometimes plastic) that I had seen at various places in Japan. Often there were as many as twenty grouped together, but always they had red cloths on their heads and shoulders. I have since learned that they honored a bodhisattva named Jizo, whose function is to help those in danger of the realms of hell, and that these were memorial statues, sometimes for aborted children (a theme also in the novel). Red, according to folk belief in Japan, is the color thought to "expel the devil." <end quote from Dreams, Myths & Fairy Tales in Japan; Einsiedeln, Switzerland, Daimon, 1995.>

- Color Red in Chinese Mythology

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_New_Year

According to tales and legends, the beginning of Chinese New Year started with the fight against a mythical beast called the Nien (Chinese: 年; pinyin: nián). Nien would come on the first day of New Year to devour livestock, crops, and even villagers, especially children. To protect themselves, the villagers would put food in front of their doors at the beginning of every year. It was believed that after the Nien ate the food they prepared, it wouldn’t attack any more people. One time, people saw that the Nien was scared away by a little child wearing red. The villagers then understood that the Nien was afraid of the colour red. Hence, every time when the New Year was about to come, the villagers would hang red lanterns and red spring scrolls on windows and doors. People also used firecrackers to frighten away the Nien. From then on, Nien never came to the village again. The Nien was eventually captured by Hongjun Laozu, an ancient Taoist monk. The Nien became Hongjun Laozu's mount.

- HINDU GODDESS KALI

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kali

Kali wears children's corpses as earrings (probably representing natural infant mortality and childhood mortality from causes such as disease). Editor’s Note. This may be related to Japanese fox lore and the Japanese deity Daikokuten; also to Hindu Dakini.

- HINDU TRIPURA

www.clas.ufl.edu/users/gthursby/tantra/kaliyan.htm

If you should see a red flower or red clothes - the essence of Tripura - prostrate yourself like a stick on the ground and recite the following mantra: ”Tripura, destroyer of fear, coloured red as a bandhuka blossom! Supremely beautiful one, hail to you, giver of boons.“

Tripura. Lalita means She Who Plays. All creation, manifestation and dissolution is considered to be a play of the Devi or the goddess. Mahatripurasundari is her name. She is the transcendent beauty of the three cities, a description of the goddess as conqueror of the three cities of the demons, or as the triple city (Tripura), but really a metaphor for a human being. Tripura is the ultimate, primordial Shakti, the light of manifestation. She, the pile of letters of the alphabet, gave birth to the three worlds. At dissolution, She is the abode of all tattvas, still remaining Herself - Vamakeshvaratantra. What is Shri Vidya and what relationship does it have to the goddess Lalita and to her yantra, the Shri Yantra? Vidya means knowledge, specifically female knowledge, or the goddess, and in this context relates to her aspect called Shri, Lalita or Tripurasundari whose magical diagram is called the Shri Yantra. She is a red flower, so her diagram is a flower too.

Editor’s Note: Who is Tripura ?? What are the three cities of demons? Why the association with the color red?

LEARN MORE ABOUT COLOR RED

- PMJS (Pre-Modern Japanese Studies). A informative thread about the color red in Japan.

- Daruma, Smallpox and the Color Red, The Double Life of a Patriarch

A wonderful article by Professor Bernard Faure, Stanford Univ.

- The Red Thread: Buddhist Approaches to Sexuality.

Princeton University Press, 1998. Book by Bernard Faure.

- Patrons of Children and Motherhood in Japan (this site)

- Red = corresponds to fire (one of the five elements), and is associated with summer, the Phoenix, south (direction), heart (organs), burning (smell), bitter (taste), and sight (actions). For many more associations, please see www.friesian.com/elements.htm.

- Color Red Outside Japan webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/color/reds2.html

Interesting review of red’s association with sickness in Germany and symbolism in other nations.

- Gogyousetsu 五行説 aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/g/gogyousetsu.htm

Literally “theory of five elements.” A basic principle of Chinese geomancy and cosmology adapted in Japanese garden design. The five elements (with their related colors and directions) are:

- wood (blue-green, east)

- fire (red, south)

- metal (white, west)

- water (black, north)

- earth (yellow, center)

- More more on Five Elements, click here (this site).

- Pages by Gabi Greve

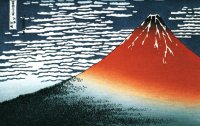

Woodblock - Just for Fun. Red Fuji = Japanese “Aka Fuji” = 1837 AD. Artist = Hokusai Katsushika

One of the famous “36 Views of Mount Fuji” by Hokusai. Traditionally called "Mount Fuji in Clear Weather."

First Published Dec. 4, 2005 // Last Update May 18, 2010

|

|