|

|

|

|

|

FUKUROKUJU 福禄寿

God of Wealth, Happiness, Longevity

Fuku 福 = Wealth, Roku 禄 = Happiness, Ju 寿 = Longevity

Origin = Chinese Taoism

One of Japan’s Seven Lucky Gods

Animal Associations = Bat, tortoise, crane, stag

Associated Virtue = Popularity

|

SEVEN VIRTUES

Japan's Seven Lucky Gods are a popular grouping of deities

that appeared from the 15th century onward. The members of

the grouping changed over time, but a standardized set

appeared by the 17th century. In the 17th century, Japanese

monk Tenkai (who died in 1643 and was posthumously named

Jigen Daishi) symbolized each of the seven with an essential

virtue for the Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu (1623-1650 AD).

The seven virtues are:

- Candour (Ebisu)

- Fortune (Daikokuten)

- Amiability (Benzaiten)

- Magnanimity (Hotei)

- Popularity (Fukurokuju)

- Longevity (Juroujin)

- Dignity (Bishamonten)

References: Flammarion Iconographic Guide - Buddhism

|

1. Fukurokuju, Private garden, Kamakura, Japan (1928) <Photo Schumacher>

2, 3, 4 Fukurokuju Ceramic Statues, Private Collection <Photos Robert Yellin>

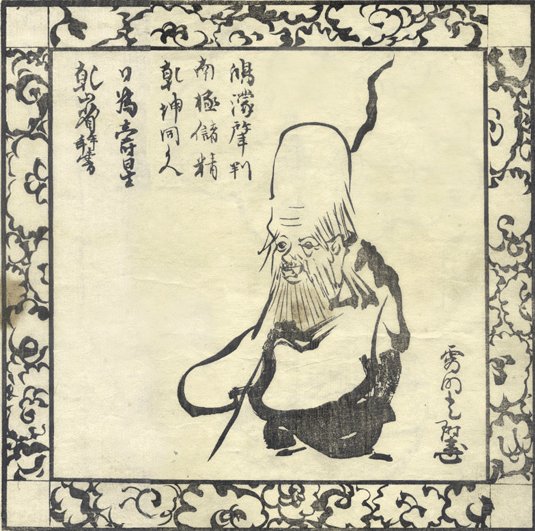

Male. The god of wealth, happiness, and longevity. A personification of the southern polar star (Jp. = Nankyokusei 南極星) and a deity who is often confused with Jurōjin (another god of Taoist origin and member of the Seven Lucky Deities). The two are said to inhabit the same body, but to represent different manifestations of the same celestial body <Source: Butsuzō-zu-i>. The bearded Fukurokuju has an unusually elongated forehead. He is typically shown in the customary garments of a Chinese scholar and holding a cane with a scroll attached to it. He may also have a tortoise or crane near him (both creatures are icons of longevity in China and Japan).

Fukurokuju probably originated from an old Chinese tale about a mythical Chinese Taoist hermit sage renowned for performing miracles in the Northern Song period (960 and 1279). In China, this hermit (also known as Jurōjin) was thought to embody the celestial powers of the south polar star . Fukurokuju was not always included in the earliest representations of the seven in Japan. He was instead replaced by Kichijōten (goddess of fortune, beauty, and merit). He is now, however, an established member of the Seven Lucky Gods.

|

|

SEVEN LUCKY GODS MENU

Intro Page

Benzaiten

Bishamonten

Daikokuten

Ebisu

Fukurokuju

Hotei

Jurōjin

Says the modern reprint of the Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙: “Fukurokuju and Jurōjin are the same deity. Along with the southern pole star, they represent the three other stars 三星 of the Southern Cross, all rolled into one. When considered an amalgamation of the 福星 (wealth star), 録星 (happiness star), and 寿星 (longevity star), they appear with the crane or tortoise and bring the gift of longevity to devotees.” The three stars spell 福録寿, aka Fukurokuju.

Fukurokuju from the

1690 Butsuzō-zu-i

|

|

|

MORE ABOUT FUKUROKUJU

|

|

Modern stone carving, Kamakura

Fukurokuju with elongated forehead.

Photo Mark Schumacher

|

|

Says JAANUS: Fukurokuju 福禄寿 (Chinese = Fulushou). A popular deity of wealth (fuku 福), happiness (roku 禄), and longevity (ju 寿), and also associated with the Southern Pole Star (Nankyokusei 南極星). The origin of the god may lie in the story by Yangzheng 陽城 (Jp. = Yousei), advisor to Emperor Wu (Jp. = Butei 武帝, 464-549) of the Liang 梁 dynasty, which holds that Fukurokuju counselled the emperor to end conscription of slaves from a certain province and thus earned the reputation as a god of happiness in the region. An auspicious subject in Chinese and Japanese painting, he is usually accompanied by a bat and tortoise, and occasionally a stag with a small body and elongated bald head, Fukurokuju is often confused with Jurōjin 寿老人, but can be differentiated by the animals shown with him. <end quote> Says JAANUS: Fukurokuju 福禄寿 (Chinese = Fulushou). A popular deity of wealth (fuku 福), happiness (roku 禄), and longevity (ju 寿), and also associated with the Southern Pole Star (Nankyokusei 南極星). The origin of the god may lie in the story by Yangzheng 陽城 (Jp. = Yousei), advisor to Emperor Wu (Jp. = Butei 武帝, 464-549) of the Liang 梁 dynasty, which holds that Fukurokuju counselled the emperor to end conscription of slaves from a certain province and thus earned the reputation as a god of happiness in the region. An auspicious subject in Chinese and Japanese painting, he is usually accompanied by a bat and tortoise, and occasionally a stag with a small body and elongated bald head, Fukurokuju is often confused with Jurōjin 寿老人, but can be differentiated by the animals shown with him. <end quote>

Says the Flammarion Iconographic Guide: This semi-deity of Chinese origin is perhaps the divine representation of a Taoist hermit sage of the Song period. He is also said to be the god of the Southern Cross, or wisdom, virility, fertility, and longevity. He was sometimes, but seldom, replaced in the assembly of the Seven Lucky Gods by Kichijouten. Fukurokuji is usually represented in the form of a little old man, with beard and moustache, with a bald head three times the height of his body. This disproportionate head sometimes assumes phallic forms and is then covered with a cloth cap. He holds a long knobbly staff to which a book is attached. In paintings he is often shown in the company of a crane, the Taoist symbol of longevity. In sculpture, his hands are usually hidden in wide sleeves. Sometimes confused with Jurōjin, he is almost never invoked as a separate deity. <end Flammarion quote>

|

|

Says Chiba Reiko, author of The Seven Lucky Gods of Japan (1966):

- Among the seven, he is the only one credited with being able to revive the dead.

- He is considered a Chinese Taoist sennin 仙人 (immortal), one able to exist without food. Said to have walked the earth in the Northern Song period (960 and 1279).

- Old man who has enormously long head, said to be more than half his height.

- Fukurokuju loves to play chess and once said “one who can look upon a chess game without comment is a great man.” There is a story related to this. A farmer, returning to his home, passed two old men playing a game of chess. As he quietly watched the match, each slow move after another, it seemed to him that the beard of one contestant grew longer. During the long match, the bearded man gave the farmer some strange-tasting food to take away his hunger. Much later in the day, the farmer realized the day had passed, and politely bid farewell to the players. He rushed home, only to discover it no longer existed. After making inquiries, he discovered that 200 years had passed as he watched the chess game.

|

|

|

Says the Mingeikan (Japan Folk Craft Museum, Tokyo): ”This painting demonstrates the happy and humorous natures of these two members of the group of Seven Deities. Daikoku is the deity of prosperity, while Fukurokuju is the deity of longevity. Daikoku is almost naked, clothed only in a loincloth and wearing a red hood. Holding a razor in his right hand, he must climb a ladder in order to shave Fukurokuju's head, since it is so elongated. The painting illustrates the human qualities of deities, who seem less than godlike in such poses, showing that the immortals have as many foibles as us ordinary folk.” <end quote>

PHOTO AT RIGHT

Daikoku Shaving Fukurokuju, 18th Century

OTSU-E PAINTING, COURTESY THE MINGEIKAN

THE JAPAN FOLK CRAFTS MUSEUM

Otsu-e (Also spelled Otsue), Edo Period

Popular Paintings of Goblins & Deities in Japanese Folk Art

|

|

|

|

|

|

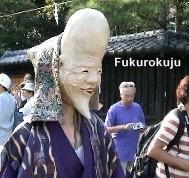

Goryō (Goryo) Jinja Shrine 御霊神社

This shrine in Kamakura City is one of the seven sites of the Kamakura Pilgrimage to the Seven Lucky Gods. The shrine’s treasure hall houses ten old masks with amusing, exaggerated expressions. One of the masks is of Fukurokuju. The annual festival is from September 12th to 18th. On the last day is a procession (menkake gyoretsu) of local people wearing these weird masks -- the procession originated in the time of Minamoto no Yoritomo 源頼朝 (1147-99), who established the shogunate in Kamakura. The procession is an Intangible Folk Cultural Asset of Kanagawa Prefecture. Learn about the shrine here.

|

Fukurokuju Mask, Goryō Jinja Shrine

御霊神社, Kamakura. Photo this E-Site

|

|

|

|

|

Fukurokuju by Ogata Kōrin 尾形光琳 (1658-1716), elder brother of Ogata Kenzan 尾形乾山(1663-1743). Both were

well-known artists of the Edo era (1603-1868). Fukurokuju is often confused with Jurōjin (another god of Taoist origin and a

member of the Seven Lucky Deities). The two are said to inhabit the same body, but to represent different manifestations

of the southern pole star. This image was in fact labeled Jurōjin, but given the elongated head, it is obviously Fukurokuju.

Photo Source This J-Site.

Seven Gods of Fortune (1882), by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka 芳年月岡 (1839-1892). Photo this J-site.

Here Fukufokuju uses his elongated forehead to write calligraphy while the others look on gleefully.

One of the seven is perched beneath Fukurokuju’s head, peeking at the canvas.

|

|

|

|

|

SOURCES

|

|

- Butsuzō zui 仏像図彙 (Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images). Published in 1690 (Genroku 元禄 3). A major Japanese dictionary of Buddhist iconography. Hundreds of black-and-white drawings, with deities classified into categories based on function and attributes. For an extant copy from 1690, visit the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library. An expanded version, known as the Zōho Shoshū Butsuzō-zui 増補諸宗仏像図彙 (Enlarged Edition Encompassing Various Sects of the Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images), was published in 1783. View a digitized version (1796 reprint of the 1783 edition) at the Ehime University Library. Modern-day reprints of the expanded 1886 Meiji-era version, with commentary by Ito Takemi (b. 1927), are also available at this online store (J-site). In addition, see Buddhist Iconography in the Butsuzō-zui of Hidenobu (1783 enlarged version), translated into English by Anita Khanna, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 2010.

- JAANUS. Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. A wonderful online dictionary compiled by the late Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent. It covers both Buddhist and Shinto deities in great detail. Over 8,000 entries. Written in English, yet presenting all key terms in Japanese.

- Buddhism (Flammarion Iconographic Guides)

, by Louis Frederic, Printed in France, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. A highly illustrated volume, with special significance to those studying Japanese Buddhist iconography. Includes many of the myths and legends of mainland Asia as well, but its special strength is in its coverage of the Japanese tradition. Hundreds of accompanying images/photos, both B&W and color. Frederic uses many images from the Butsuzō zui (see prior entry) , by Louis Frederic, Printed in France, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. A highly illustrated volume, with special significance to those studying Japanese Buddhist iconography. Includes many of the myths and legends of mainland Asia as well, but its special strength is in its coverage of the Japanese tradition. Hundreds of accompanying images/photos, both B&W and color. Frederic uses many images from the Butsuzō zui (see prior entry)

- Essentials of Buddhist Images: A Comprehensive Guide to Sculpture, Painting, and Symbolism. By Kodo Matsunami. Paperback; first English edition March 2005; published by Omega-Com. Matsunami (born 1933) is a Jōdo-sect 浄土 monk, a professor at Ueno Gakuen University, and chairperson of the Japan Buddhist Federation. He received the government's Medal of Honor (褒章 hōshō), Blue Ribbon, for his achievements in public service. Says Matsunami: “Bishamonten protects from disaster and bodily harm. Daikoku satisfies the deisre for food. Benzaiten represents sexual desire. Hotei brings laughter, and Ebisu grants wealth.

- Tobifudo Deity Dictionary. Ryūkozan Shōbō-in Temple 龍光山正寶院 (Tokyo). Tendai Sect. Jump to its Fukurokuju page.

- The Seven Lucky Gods of Japan

, by Chiba Reiko. Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1966. Pages 35-38. , by Chiba Reiko. Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1966. Pages 35-38.

- UCLA Center for East Asian Studies, Educational Resources from teacher Samantha Wohl, Palms Middle School, Summer 2000. See Wohl’s Materials List (based on Chiba Reiko’s book).

LEARN MORE

This is a side page

Return to Seven Lucky Gods Main Page

|

|