|

|

|

|

|

DRAGON

Character for Dragon

Ryū or Ryu = Japan; Lóng or Long = China

ORIGIN = CHINA

Protector of Buddhist Law

Symbol of Imperial Power

Guardian of Eastern Direction

Controller of Rain & Tempests

Guardian of the Tide Jewels

Bringer of Wealth & Fortune

Magical Shape Shifter

ASSOCIATIONS

East, Spring, Blue / Green

Wood, Water, Yang Energy

Clouds, Rain, Storms

Messenger = Turtle

Seven Eastern Lunar Mansions

Member of the TENBU

Member of the HACHIBUSHUU

Member of the NAGA (Sanskrit)

One of FOUR CELESTIAL EMBLEMS

SPELLINGS FOR THE DRAGON

SANSKRIT, CHINESE, JAPANESE

- Naga (Sanskrit for all serpentine

creatures, including the dragon)

- Lóng, Long 龍 (Chinese for dragon)

- Qinglóng or Qinglong 青龍

(Chinese = blue/green dragon)

- Seiryū, Seiryu 青龍 (Jp. = blue/green dragon)

- Ryū, Ryu, Ryuu 龍 or 竜 (Japanese)

- Tatsu 辰 (Japanese)

- Ryū-ō, Ryu-o, Ryuu-ou 龍王, 竜王.

Dragon Kings (Japanese)

- Ryūjin, Ryujin, Ryuujin 龍神, 竜神 (Japanese)

- Yong 용 (Korean)

|

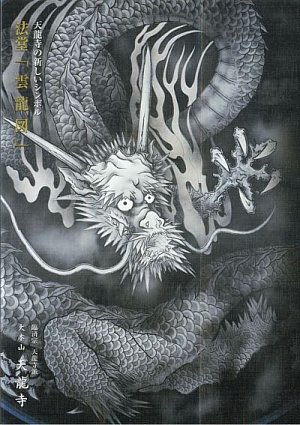

Dragons often adorn temple structures in Japan.

Dragon at Ryūtaku-ji Temple 龍沢寺 (Shizuoka)

Woodblock by Utagawa Kunisada II, 1860

See full image near bottom of page.

Modern Brass Dragon, Price = $70

Details & buy options at our estore. View catalog.

|

|

DRAGON MYTHOLOGY. A mythological animal of Chinese origin, and a member of the NAGA (Sanskrit) family of serpentine creatures who protect Buddhism. Japan's dragon lore comes predominantly from China. Images of the reptilian dragon are found throughout Asia, and the pictorial form most widely recognized today was already prevalent in Chinese ink paintings in the Tang period (9th century AD). The mortal enemy of the dragon is the Phoenix, as well as the bird-man creature known as Karura. In contrast to Western mythology, Asian dragons are rarely depicted as malevolent. Although fearsome and powerful, dragons are equally considered just, benevolent, and the bringers of wealth and good fortune. The dragon is also considered a shape shifter who can assume human form and mate with people.

Dragons figure importantly in folk beliefs throughout Asia, and are dressed heavily in Buddhist garb. In India, the birthplace of Buddhism around 500 BC, pre-Buddhist snake or serpentine-like creatures known as the NAGA were incorporated early on into Buddhist mythology. Described as “water spirits with human shapes wearing a crown of serpents on their heads” or as “snake-like beings resembling clouds,” the NAGA are among the eight classes of deities who worship and protect the Historical Buddha. Even before the Historical Buddha (Siddhartha, Guatama) attained enlightenment, the NAGA King Mucilinda (Sanskrit) is said to have protected Siddhartha from wind and rain for seven days. This motif is found often in Buddhist art from India, represented by images of the Buddha sitting beneath Mucilinda’s hood and coils. (Above paragraph adapted from book by M.W. De Visser.) Dragons figure importantly in folk beliefs throughout Asia, and are dressed heavily in Buddhist garb. In India, the birthplace of Buddhism around 500 BC, pre-Buddhist snake or serpentine-like creatures known as the NAGA were incorporated early on into Buddhist mythology. Described as “water spirits with human shapes wearing a crown of serpents on their heads” or as “snake-like beings resembling clouds,” the NAGA are among the eight classes of deities who worship and protect the Historical Buddha. Even before the Historical Buddha (Siddhartha, Guatama) attained enlightenment, the NAGA King Mucilinda (Sanskrit) is said to have protected Siddhartha from wind and rain for seven days. This motif is found often in Buddhist art from India, represented by images of the Buddha sitting beneath Mucilinda’s hood and coils. (Above paragraph adapted from book by M.W. De Visser.)

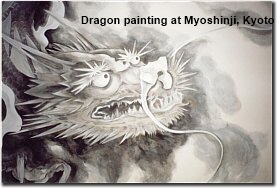

In China, however, dragon lore existed independently for centuries before the introduction of Buddhism. Bronze and jade pieces from the Shang and Zhou dynasties (16th - 9th centuries BC) depict dragon-like creatures. By at least the 2nd century BC, images of the dragon are found painted frequently on tomb walls to dispel evil. Buddhism was introduced to China sometime in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. By the 9th century AD, the Chinese had incorporated the dragon into Buddhist thought and iconography as a protector of the various Buddha and the Buddhist law. These traditions were adopted by the Japanese (Buddhism did not arrive in Japan until the mid-6th century AD). In both China and Japan, the character for "dragon" (龍) is used often in temple names, and dragon carvings adorn many temple structures. Most Japanese Zen temples, moreover, have a dragon painted on the ceiling of their assembly halls. See below photos.

Dragon, Ceiling Painting at Tenryū-ji Temple 天龍寺, Kyoto. Rinzai Zen Sect. Tenryū-ji is also a World Heritage Site.

This ceiling painting was first created in 1899, and restored in 1997. It measures about 18 meters across.

Drawn on Japanese paper attached to ceiling plates (tiles). Photo scanned from temple catalog.

Tenryū translates directly as “Heaven Dragon.”

Close-up of above Tenryū-ji ceiling painting

DRAGON SYMBOLISM - ORIGINS IN CHINA

FOUR GUARDIANS OF FOUR COMPASS DIRECTIONS

Click any image above to jump to that creature (takes you to another page).

In both Chinese and Japanese mythology, the dragon is one of Four Legendary Creatures guarding the four cosmic directions (Red Bird - S, Dragon - E, Tortoise - N, and the Tiger - W). The four, known as the Four Celestial Emblems, appear during China's Warring States period (476 BC - 221 BC), and were frequently painted on the walls of early Chinese and Korean tombs to ward off evil spirits. The Dragon is the Guardian of the East, and is identified with the season spring, the color green/blue, the element wood (sometimes also water), the virtue propriety, the Yang male energy; supports and maintains the country (controls rain, symbol of the Emperor's power). The Guardian of the South, the Red Bird (aka Suzaku, Hō-ō, Phoenix), is the enemy of the dragon, as is the bird-man Karura. Actually, the Phoenix is the mythological enemy of all Naga, a Sanskrit term covering all types of serpentine creatures, including snakes and dragons. The Dragon (East) and Phoenix (South) both represent Yang energy, but they are often depicted as enemies, for the Dragon represents the element wood, while the Phoenix signifies the element fire. However, they're also often depicted together in artwork as partners. The Dragon is the male counterpart to the female Phoenix, and together they symbolize both conflict and wedded bliss -- the emperor (dragon) and the empress (phoenix). For many more details, see the Phoenix page and Four Guardians of the Compass page.

|

Dragon water fountain

at Ryūtakuji Temple

|

|

Excerpt from "Myths & Legends of Japan" Excerpt from "Myths & Legends of Japan"

by F. Hadland Davis.

The Dragon has the head of a camel, horns or a deer, eyes of a hare, scales of a carp, paws of a tiger, and claws resembling those of an eagle. In addition it has whiskers, a bright jewel under its chin, and a measure on the top of its head which enables it to ascend to Heaven at will. This is merely a general description and does not apply to all dragons, some of which have heads of so extraordinary a kind that they cannot be compared with anything in the animal kingdom. The breath of the Dragon changes into clouds from which come either rain or fire. It is able to expand or contract its body, and in addition it has the power of transformation and invisibility. The ancient Chinese Emperor Yao was said to be the son of a dragon, and many rulers of that country were metaphorically referred to as dragon-faced." <end excerpt by Hadland>.

TYPES OF DRAGONS

In both Chinese and Japanese mythology, the dragon is closely associated with the watery realm, and in artwork is often surrounded by water or clouds. In myth, there are four dragon kings who rule over the four seas (which in the old Chinese conception limited the habitable earth). In China, a fifth category of dragon was added to these four, for a total of five dragon types:

- Celestial Dragons who guard the mansions of the gods

- Spiritual Dragons who rule wind & rain but can also cause flooding

- Earth Dragons who cleanse the rivers & deepen the oceans

- Treasure-Guarding Dragons who protect precious metals & stones

- Imperial Dragons; dragons with five claws instead of the usual four

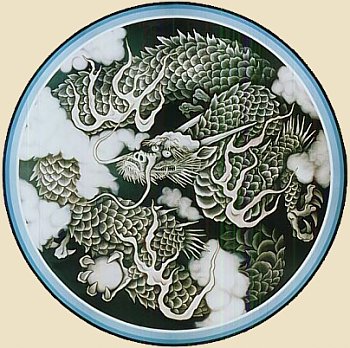

Five-clawed dragon at

Kenchō-ji Temple (Kamakura, Japan)

See above for details.

Painted in the 1990s.

Here, Japanese dragon

iconographcy does not

abide with traditional

Chinese notions about

the number of claws. |

|

NUMBER OF CLAWS NUMBER OF CLAWS

Five, Four, Three Claws

According to most sources, the dragon of China and Japan resemble each other, with the exception that the Japanese dragon has only three claws, while that of the Celestial Kingdom (China) has five.

www.khandro.net

Much has been made of these distinguishing characteristics among Asian dragons. There is an iconographic convention in which the common dragon has only four claws. The five-clawed dragon, in contrast, is reserved for the Chinese imperial family, while the colonial type (such as the Japanese dragon) has only three claws.

Another View of Claws, From Wikipedia

Chinese or Korean imperial dragons have five toes on each foot; Indonesian dragons have four and Japanese dragons have three. To explain this phenomenon, Chinese legend states that although dragons originated in China, the further away from China a dragon went the fewer toes it had, and dragons only exist in China, Korea, Indonesia, and Japan because if they travelled further they would have no toes to continue. Japanese legend has an opposing story, namely that dragons originated in Japan, and the further they traveled the more toes they grew and as a result, if they went too far they would have too many toes to continue to walk properly. These theories are rejected in Korea and Indonesia. Another interpretation: according to several sources, including official documents from earlier times, ordinary Chinese dragons had four toes -- but the Imperial Dragon had five. It was a capital offense for anyone other than the emperor to use the five-clawed dragon motif. Korean sources seem to disagree (or perhaps agree) with this theory, as the Imperial dragon in Gyeongbok Palace has seven claws, implying its superiority over the Chinese Dragon. Of course, this dragon image is hidden in the rafters of the palace and not entirely in view, even to those who know it is there, suggesting that while the ancient Koreans viewed it as superior, they also knew that it would be offensive to the Imperial Chinese Court.

Unryū, Cloud Dragon. Ceiling Painting, Late 1990s, Kenchō-ji Temple, Kamakura

Painted by artist Koizumi Junsaku on 48 panels. Took about three years to create, and measures

approx. 10 meters by 12 meters in size. Photo Courtesy Kenchōji Web Site.

Close-up of above Kenchō-ji Temple ceiling painting.

Founded in 1251, this temple was the chief monastery for the five great Zen monasteries that thrived in the

Kamakura era (1185-1333). It became the center of Zen Buddhism thanks to strong state patronage,

and was home to the first landscape garden laid out in the Zen style. However, unlike many other Zen temples

in Japan, Kenchō-ji never had its own dragon painted on the ceiling of its assembly hall. This painting was

commissioned to celebrate the 750th anniversary of the temple’s founding, and was unveiled in a public

viewing in May & June 2003. This photo is from the event’s promotional poster.

COLOR OF DRAGON ROBES

A yellow dragon is said to have presented the Chinese with a scroll inscribed with mystic characters, and this tradition is said to be the legendary origin of the Chinese system of writing. In China, yellow dragon robes are reserved for the Emporer and his family. The dragon is also used as a symbol for the Chinese Emperor, the Son of Heaven. In earlier times, the color of a dragon robe reflected the rank of its wearer. Yellow for the Emperor and Empress, apricot for the Crown Prince, and golden yellow for the emperor’s other wives.

DRAGON SYMBOLISM

DRAGON MOTIFS ON IMPERIAL ROBES

SEE STORIES BY KYOTO NATIONAL MUSEUM

Aristocrat's robe with dragon motifs. China, Qing Dynasty, 17 century

Photo courtesy metmuseum.org. Met Museum Dragon Robe #1 | Met Museum Dragon Robe #2

|

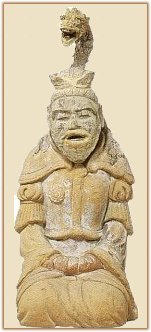

Ryū-ō 竜王 (Dragon King)

Sanskrit = Naga-Raja

7th Century

Hōryū-ji Temple

Ryū

|

|

DRAGON LORE FROM JAPAN DRAGON LORE FROM JAPAN

Origin of Dragon’s Japanese Name

In Japanese mythology, the Dragon King's Palace (Ryūgū 竜宮) is said to be located at the bottom of the sea, near the Ryūkū (Ryukyu) 琉球 Islands (Okinawa), and it belongs to Ryūjin (Ryujin) 竜神, the Japanese name for the dragon king. The palace is also known as the “Evergreen Land.” In his book Japanese Poetry, Professor B. H. Chamberlain says the Japanese word for Dragon Palace (Ryūgū) is likewise the Japanese pronunciation of the southernmost Ryūkū islands. He writes about one ode in the Man'yōshū 万葉集 (Japan's oldest anthology of verse compiled in the 8th century), which says the orange was first brought to Japan from the “Evergreen Land” lying to the south. The many-storied palace is built from red and white coral, guarded by dragons, and full of treasure, especially the Tide Jewels, which control the ebb and flow of tidal waters. Fish and other sea life serve Ryūjin as vassals, with the turtle acting as the dragon’s main messenger. On the north side of the palace there is the Winter Hall, where snow falls all the time. On the eastern side lies the Hall of Spring where butterflies visit cherry blossoms while the nightingale sings. On the southern side of the palace is the Summer Hall where crickets chirp in the warm evening. Finally, on the western side is the Autumn Hall where the maple trees glow in bright colors. For a human, a day in this palace is like 100 years on earth.

DRAGON LORE FROM JAPAN

Origin of Japan’s First Emperor, Tale of Hōri.

Tale of Hōri (Hori, Houri, Hoori). Long ago, the Dragon King’s daughter Toyotama-hime 豊玉姫命 (Princess Rich Jewel) married a hunter named Hōri no Mikoto 火遠理命 (also known as Yamasachibiko 山幸彦), who lived with her for three years in her underwater kingdom. Lonely for the site of his own country, however, Hōri returned to the upper world, but not before discovering that Toyotama was with child. The son she bore him later sired four children, one of whom was Kamuyamato Iwarebiko 神日本磐余彦, the first human emperor of Japan, who is now known as Jinmu Tennō 神武天皇. Incidentally, Hōri himself was the child of Ninigi 邇邇芸尊 (Rice Ear Ruddy Plenty) and Konohana Sakuya Hime 木花之佐久夜毘売. Ninigi was the grandson of sun goddess Amaterasu (Japan’s supreme Shintō deity). Hōri and his children thus trace their line back to Japan’s earliest gods and goddesses. For an extended version of the Hōri tale, which includes many older Shintō names for the various deities involved, please click here. This site also offers the tales of Toyotama and of Ninigi, plus a family tree of the ancient gods and goddesses of Japan.

DRAGON LORE FROM JAPAN

The Dragon, Enoshima Island, and Goddess Benzaiten

Below text courtesy of "Myths and Legends of Japan" by F. Hadland Davis, first published in 1913. Near Kamakura in a certain cave there lived a formidable dragon, which devoured the children of the village of Koshigoe 腰越. In the 6th century AD, Benzaiten (the Buddhist goddess of the sea, rivers, music, poetry, learning, and art) was determined to put a stop to this monster's unseemly behavior, and having caused a great earthquake she hovered in the clouds over the cave where the dread dragon had taken up his abode. Benzaiten then descended from the clouds, entered the cavern, married the dragon, and was thus able, through her good influence, to put an end to the slaughter of little children. With the coming of Benzaiten there arose from the sea the famous island of Enoshima (near Kamakura), which has remained to this day sacred to Benzaiten, the Goddess of the Sea. <end Hadland quote> This story first appeared in the Enoshima Engi 江ノ島縁起, written in 1047 AD by Japanese Buddhist monk Kokei 皇慶 (977?-1049). The link between Benzaiten and the dragon is not surprising, as Benzaiten’s messenger is a snake, and the dragon is classified as a type of serpent (known in Sanskrit as the Naga). This legend has variations. According to Wikiipedia: “The goddess rejected the dragon's proposal and made it understand that it (the dragon) had been doing wrong by plaguing the villagers. Ashamed, the dragon promised to cease its wrong-doing. It then faced south (devotedly facing the island where Benzaiten lived) and changed into a hill. To this day, the hill is known as Dragon's Mouth Hill (Tatsu-no-kuchi yama 龍の口山). <end quote>

|

Mitsu Uroko 三つ鱗

Hōjō Family Crest

|

|

DRAGON LORE FROM JAPAN DRAGON LORE FROM JAPAN

Hōjō Clan (Regents of Kamakura),

Hōjō Family Crest & the Dragon

According to legend, Tokimasa Hōjō 北条時政 (1138-1215), the first Hōjō regent of the Kamakura shōgunate, visited a cave on Enoshima Island (near Kamakura). He prayed to the dragon living in the cave to grant prosperity to the Hōjō clan. The wish was granted, and even today a statue of the dragon is enshrined within the cave. As a token of this promise, the dragon left behind three scales, which are reportedly the origin of the three triangles of the Hōjō family crest, known as the Mitsu Uroko 三つ鱗 (three scales).

DRAGON LORE FROM JAPAN

Rain from Ryūjin (Rain from the Dragon King). In both China and Japan, the dragon is associated closely with rain, storms, and clouds, and it is the dragon who produces rain. In the Heian Period (794-1185), two Buddhist temples -- Tōji (East Temple) and Sai-ji (West Temple) -- shared control of Japan’s religious world, and an interesting legend grew out of the power struggle between the two temples. Envious of Kūkai 空海 (774-835), for his fame as head of Tōji Temple, a priest named Shubin 守敏 of Sai-ji Temple used a charm to entrap Ryūjin in a jar, thereby causing an extensive drought. Challenged by Shubin to a contest at Shinsen Garden, Kūkai dispelled the curse of Shubin, and set the Ryūjin free to cause rain to fall.

DRAGON LORE FROM JAPAN DRAGON LORE FROM JAPAN

Tale of Urashima

Once there was a young fisherman named Urashima 浦島, who caught a tortoise in his nets. But as tortoises are said to live thousands of years, Urashima thought it best to set the creature free. Little did he know, but this turtle was Otohime 乙姫, the dragon king's daughter, in disguise. (Note: In Japanese mythology, the turtle is the messenger of the dragon.) The turtle-princess invited the young man to her father's court where she appeared to him in the shape of a beautiful women, and married him. After three days, Urashima felt a strong desire to visit his aging parents. But when he returned to his land, he discovered that 300 years had passed (one day in the dragon kingdom represents 100 years for humans). Since all his loved ones had long since departed, Urashima was stricken with grief, and desired to return to this dragon wife. Not knowing how to return to the dragon palace, Urashima opened the magic box (Tamate Bako 玉手箱, or Box of the Jewel Hand) his wife had given him as a keepsake of their love. But she had told him never to open the box. When he opened the box, hoping to find a way back to her, he immediately lost his youth, became old and wrinkled, and fell dead upon the ground.

DRAGON LORE FROM JAPAN

Tale of Tide Jewels & Empress Jingū

Ryūjin (dragon deities) control the tidal flows with the magical Tide Jewels (the Flood Tide Jewel and the Ebb Tide Jewel). Long ago the Empress Jingu 神功天皇 planned an invasion of Korea. She prayed to Ryūjin and sent Isora (the Spirit of the Seashore) to the dragon king’s temple to request the Tide Jewels. There he was given the Tide Jewels to present to the empress. With the magic jewels in hand, the empress set sail with her fleet to Korea. When she saw the Korean fleet sail out to confront them, she quickly threw the Low Tide Jewel into the sea, and the tide receded immediately, beaching the Korean fleet. As the Koreans jumped out of their vessels onto the mudflats, the empress threw the High Tide Jewel into the water and a tidal wave came along, drowning all the Korean fighters. The Japanese fleet was carried by the tital wave to the Korean coast, into the harbor, and to victory. Later on, after Empress Jingū’s son has grown into a fair and wise boy, legend says that Ryūjin personally presented the little prince (Prince Ōjin 応神) with the Tide Jewels.

DRAGON LORE FROM JAPAN

God of Fire Fighters -- Dragon Tattoos

http://208.55.77.56/alterasian/arttattooirezumi4.html

Perhaps the most ubiquitous of all Japanese mythological beasts tattooed in the West is the dragon. Dragons are clearly very alluring creatures, and it is as common to see a tattoo of a dragon in Britain as it is in Japan. Because the dragon can live in both air and water, it is believed to offer protection from fire. For this reason it was often chosen by Edo-period fire fighters who tattooed themselves superstitiously for protection in their work. For photos of many dragon tattoos, please click here (outside site).

|

Censer of leaping carp transforming into dragon. Unknown artist. China 17th century, Ming Dynasty. Photo Courtesy Phoenix Art Museum.

See Shachihoko page for related story.

|

|

DRAGON LORE FROM CHINA DRAGON LORE FROM CHINA

The Carp Who Became a Dragon

The carp (Jp. = Koi 鯉) transforming into a dragon is a common artistic theme from old China. This theme is based on a Chinese legend (Jp. = Koi-no-Takinobori 鯉の滝登り) wherein carp swim, against all odds, up a waterfall known as the “Dragon Gate” at the headwaters of China’s Yellow River. The gods are very impressed by the feat, and reward the few successful carp by turning them into powerful dragons. The story symbolizes the virtues of courage, effort, and perseverance, which correspond to the nearly impossible struggle of humans to attain Buddhahood. In modern Japan, temples and shrines commonly stock their garden ponds with carp, which grow to enormous sizes in a variety of colors. Says JAANUS: Koi-no-Takinobori is the Japanese name for a Chinese legend of a carp that became a dragon after swimming up a waterfall at the headwaters of the Yellow River. This auspicious theme, a parable of effort and success, is linked to the Japanese Boys Day Festival (5th day of fifth month) when carp streamers (koinobori 鯉のぼり) are displayed. The theme was depicted in Edo period art, as for example in the painting by Maruyama Oukyo 円山応挙 (1733-95; Daijouji 大乗寺, Hyogo) or prints by ukiyo-e 浮世絵 artists. <end JAANUS quote>

Dragon Star Constellation Dragon Star Constellation

From "Encyclopedia of Myth and Legend:

Chinese Mythology" by Derek Walters

In complete contrast to Western mythology, however, dragons are rarely depicted as malevolent. They may be fearsome and very powerful, and all stand in awe of the dragon-kings, but they are equally considered just, benevolent, and the bringers of wealth and good fortune. There are, of course, legends of the various immortals battling against evil dragons, but such monsters would be foreign ones. Local dragons are to be respected, feared, and petitioned as one would petition a just and honest ruler. For this reason, the dragon symbol is the sign of authority, being worn on the robes of the Imperial family and nobility.

Dragons are generally considered to be aquatic, living in lakes, rivers and the sea, the larger the expanse of water, the more powerful the dragon. Nevertheless, there are dragons which inhabit the heavens, one quarter of the sky being called the Palace of the Green Dragon, in reference to the stars which in Chinese astronomy constitute the Constellation of the Dragon. Even so, the appearance of the Dragon constellation is said to herald the rainy season (end quote from Walters).

28 Moon Lodges, 28 Lunar Mansions

An ancient astrological grouping from India and China that refers to 27 or 28 points that the moon passes through in one month and the associated star constellations found in the cosmic background. Each of these points (constellations) is associated with a deity. The 28 are divided into four clusters, with each cluster made up of seven constellations. The four clusters represent the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, west). Each cluster is associated with one of Four Celestial Emblems (turtle, red bird, dragon, white tiger), a Buddhist guardian deity (the Four Heavenly Kings), a season, a color, and numerous other attributes. See 28 Moon Lodges page for full details.

|

EAST

Seven Lunar Mansions of the Blue-Green Dragon

(Two Common Japanese Groupings for Seven Eastern Moon Lodges)

|

|

SEIRYUU 青龍 (Dragon)

East, Blue-Green

Spring, Wood

|

|

|

GROUPING ONE - CHINA, JAPAN

Chinese | Sanskrit Names

Eastern Moon Lodges

Source: Shukuyō-kyō 宿曜経

|

GROUPING TWO - JAPAN

Deities in GENZU MANDALA 現図曼荼羅

Shingon/Tendai Deities (Celestial Females)

Jp. Reading | Chinese | (Sanskrit) | Deity Name

|

|

1

|

Kakushuku 角宿 Citrā

|

1

|

Bōshuku 昴宿 (Krttika) 作者天

|

|

2

|

Kōshuku 亢宿 Niṣṭyā (or Svāti)

|

2

|

Hisshuku 畢宿 (Rohini) 木者天

|

|

3

|

Teishuku 氐宿 Viśākhā

|

3

|

Shishuku 觜宿 (Mrgasiras) 烏頭天

|

|

4

|

Bōshuku 房宿 Anurādhā

|

4

|

Sanshuku 参宿 (Ardra) 米湿天

|

|

5

|

Shinshuku 心宿 Rohiṇī, Jyeṣṭhaghnī

|

5

|

Seishuku 井宿 (Punarvasu) 服財天

|

|

6

|

Bishuku 尾宿 Mūlabarhaṇī (or Mūla)

|

6

|

Kishuku 鬼宿 (Pusya) 増益天

|

|

7

|

Kishuku 箕宿 Pūrva-Aṣādha

|

7

|

Ryūshuku 柳宿 (Aslesa) 不染天

|

|

DRAGON’S BUDDHIST COUNTERPART = JIKOKUTEN 持国天

Star Chart by Steve Renshaw & Saori Ihara

KEY TO BELOW LIST (corresponds to left column above)

Chinese | Meaning | Jp. Star Reading | Sanskrit Spelling | (Western Constellation

1. 角, Horns (perhaps Angle, Corner), Su Boshi, Citrā (Alpha Vir, Spica)

2. 亢, Neck, Throat, Ami Boshi, Niṣṭyā or Svāti (Kappa Vir, Virgo)

3. 氐, Root or Shoulder, Tomo Boshi, Viśākhā) (Iota Lib, Alpha Lib, Libra)

4. 房, Chamber or Breasts, Soi Boshi, Anurādhā (Delto Sco, Pi Scho, Libra)

5. 心, Heart, Nakago Boshi, Rohiṇī or Jyeṣṭhaghnī or Jyeṣṭhā (Sigma Sco, Antares)

6. 尾, Tail, Ashitare Boshi, Mūlabarhaṇī or Mūla (Mu Sco, Scorpius)

7. 箕, Basket, Mi Boshi, Pūrva-Aṣādhā (Gamma Sgr, Eta Sgr, Sagittrius)

|

|

DRACO LORE

More on Dragon Star Constellation. Text courtesy Khandro.net. Around 1,800 BC, the celestial indicator (the “pole star”) was not the modern-day North Star (Polaris), but rather Thuban, a star in the constellation known as Draco or Dragon. Draco is the 8th largest of the conventional constellations curving from the "pointers" of the Dipper (Ursa Minor) to brilliant Vega. To the observer of today, there is no bright star in the configuration. Yet, the passages in the great pyramid at Gizeh (Egypt) once acted as channels for the light of the star that is called Thuban. It is now known that those pyramids were oriented to Orion and, at the time of the building of the Sphinx, to Leo.

It has been demonstrated that Angkor Wat, the great Khmer (Cambodian) Buddhist shrine was built in alignment with this celestial formation. However, in 1,150 CE the constellation of the Dragon was upside down over the site's medieval buildings, but impressively, in the era of 10,500 BC, traces of the very earliest structures there mirrored the Dragon constellation exactly.

The transition from one ruling celestial system to another is marked in the mythologies of the world by accounts of the overthrow of Titans (Greek) or Ashuras (Indian) by Gods or Devas. Naturally, this displacement had to be justified, and so the serpentine heavenly Mother, Tiamat of the early Mesopotamians, is considered by devotees of the newer deity, Marduk, as an evil draconian monster.

The flying dragon whose abode is the heavens is universally recognized as a symbol of the Chinese culture and its people. Chinese refer to themselves as “Descendents of the Dragon.”

It is believed that on rare occasions dragons have the power to transform themselves into handsome humans who, male or female, can mate with people. For example, former Japanese Emperor Hirohito claimed descent from Princess Fruitful Jewel, daughter of a sea Dragon King. It is this belief that lies at the root of the dragon, which is often used in Asia as the crest or emblem of a royal house.

HACHIDAI RYUU-OU 八大竜王

EIGHT GREAT DRAGON KINGS IN BUDDHIST LORE

Hachidai Ryuu-ou (Eight Great Dragon Kings) are mentioned in the Lotus Sutra (HOKEKYOU 法華経) and they appear sometimes in Japanese artwork. These eight are dragon kings said to live at the bottom of the sea, apparently in reference to the eight dragon kings, each with many followers, who assembled at Eagle Peak to hear the Lotus Sutra as expounded by the Historical Buddha. According to the Kairyuo Sutra (Sutra of the Dragon King of the Sea), dragons are often eaten by giant man-birds called Garudas, their natural enemy. The Phoenix is another enemy of the dragon. Nanda Ryuuou, who is one member of the Hachidai group, can sometimes represent the whole set, as he does in the Hokke Mandala 法華曼荼羅.

Dragon, Wood Carving on Gate

at Engakuji Temple in Kita-Kamakura

|

NOTE: The below text comes from the wonderful research of the Japanese Architecture & Art Net User System (JAANUS). A visit to their online dictionary is highly recommended. Over 8000 entries. Below text reproduced with their permission. Thank you JAANUS. The photos presented below, however, are not from JAANUS, but rather from my own photos and web crawling. NOTE: The below text comes from the wonderful research of the Japanese Architecture & Art Net User System (JAANUS). A visit to their online dictionary is highly recommended. Over 8000 entries. Below text reproduced with their permission. Thank you JAANUS. The photos presented below, however, are not from JAANUS, but rather from my own photos and web crawling.

|

|

Dragon Mythology

Jp. = Ryū, Ryu, or Ryuu 龍; Also written 竜; Chn. = Lóng or Long

Mythological animal and cosmological symbol of Chinese origin. The beginnings of dragon myths are obscure, but belief in such a creature predates written history. The image of the reptilian dragon as known today throughout East Asia had achieved its form by the 9th century Tang ink painting. Typically the dragon is covered with scales, has a long serpentine body with a scalloped dorsal fin, claw-like feet and pointed tail. Its face is distinguished by small horns, large eyes with bushy brows, flaring nostrils, long whiskers and sharp teeth. The dragon is associated with water, and is often shown emerging from vapor and clouds to produce rain. Living in the sky it is considered closely related to heaven, and from early times was used as a symbol of imperial power. In addition to serving as a deity of rain and of Heaven, the blue-green dragon (seiryuu 青竜) is the directional symbol of the east, and thus one of the guardian animals of the four directions (shishin 四神). Dragons figure importantly in popular folk beliefs and Taoism, often serving as a vehicle for immortals. By the 9th century, the Chinese had incorporated the dragon into Buddhist thought and iconography as a protector of the various Buddha and the Buddhist law. For example, the character for dragon 龍 is often found in temple names. The earliest representations of dragon-like creatures are Shang and Zhou period (ca. 16th - 9th centuries BCE) bronzes and jades bearing abstract animal or monster designs. By the Warring States or Han period (ca. 8th century BC to 3rd century AD), dragons were frequently painted on tomb walls to ward off evil spirits. Beginning in the late Tang period (9th century), the dragon was painted in ink monochrome (suibokuga 水墨画). The so-called "Nine Dragons Hand Scroll" (Kyuuryuuzukan 九竜図巻, 1244, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) by Chen Rong 陳容 (Jp: Chin You, act. 1235-58) exemplifies ink painting of the subject in the Song period.

Nine Dragons Hand Scroll (Detail) - 九龍圖卷 (陳容)

Chinese, Southern Song dynasty, dated 1244

Chen Rong, Chinese, first half of the 13th century

Photo courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Large-scale dragon compositions came to be painted on the walls of imperial buildings and of temples. In painting for the Zen 禅 sects, especially, depictions of dragons and tigers (ryuuko-zu 竜虎図) were frequently paired. The famous ink paintings by Muqi 牧谿 (Jp: Mokkei, late 13th century) at Daitokuji 大徳寺, Kyoto, served as the model for countless later Japanese painted versions. Dragons came to Japan much before ink painting. Examples are found in handscrolls, such as "Charicatures of Animals" Choujuugiga 鳥獣戯画 and Kegon Engi 華厳縁起.

In Buddhist painting a dragon appears as the crown of the Dragon King (Ryū-ō 龍王 or 竜王, one of the Hachibushuu 八部衆). Japanese dragon painting reached its apogee in the late 16c-early 17c paintings by Kanou and Kaihou artists (Kanouha 狩野派, Kaihouha 海北派). It is often suggested that these dragon paintings were intended as symbols of heroic leadership because the dragon calling forth rain is a metaphor for the enlightened ruler seeking able ministers.

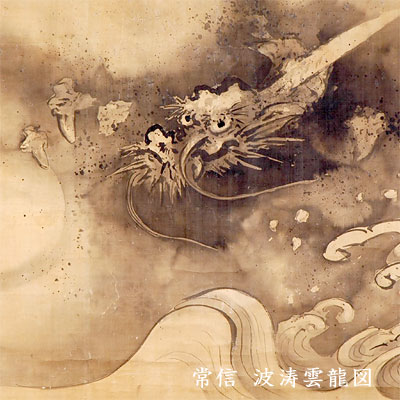

Dragon Painting

by Kano Tsunenobu 狩野常信 (Kanou School)

16th - 17th Century; Photo courtesy of:

www.honmonji.or.jp/05topic/06info/reihoden/kanou/tokubetutenji.html

DRAGIN KINGS, Ryū-ō 龍王 or 竜王

Text courtesy JAANUS. Pre-Buddhist snake or dragon deities (Skt = naga), which were later adopted into stories of the Buddha's life and into texts honoring the Buddha and propagating his teachings, are also called ryuu-ou 龍王. They live in water and have the power to control rain. In stories ryuu demand Buddhist treasures, especially relics, sometimes in exchange for quelling storms. In their kingdoms beneath the sea they guard treasures, such as jewels and Buddhist texts. Particularly when termed Dragon Kings (ryuuou), they may appear independently in paintings, or they may be shown in groups or as attendants to Buddhist deities. When water is shown in a Buddhist painting, there will often be a dragon in it. Ryuu appear in the Shougyou Mandara 請雨経曼荼羅, which was used in esoteric rituals for making rain. Individual ryuu include: Nanda 難陀, Bananda (or Batsunanda) 跋難陀, Sakara (or Shagara) 娑竭羅, Manasu 摩那斯 (or Manashi), and Zennyo 善女. There is also a group of eight dragons, the hachidai ryuuou 八大竜王, who are mentioned in the Lotus Sutra (HOKEKYOU 法華経) and also appear in art. Nanda Ryuuou, who is one of this set, may represent the whole, as he does in the Hokke Mandara 法華曼荼羅. The ryuuou may be shown entirely as dragons, as humans with snake's tails, or as humans (usually in Chinese dress) with dragons or snake hoods or some other indication of identity. If multiple heads are shown, they may indicate the identity of the ryuu. Illustrations of the Lotus Sutra may show the Dragon Princess, who, in the Devadatta chapter, achieves enlightenment. Famous images of ryuuou include that of Zennyo Ryuuou 善女龍王 of Kongoubuji 金剛峯寺, Wakayama prefecture, painted by Jouchi 定智 in 1145, and that of Nanda Ryuuou 難陀龍王 (as a honjibutsu 本地仏 of the deity of Kasuga Taisha 春日大社) of Hasedera 長谷寺, Nara, carved by Shunkei 舜慶 in 1316.

Ryō-ō, Ryou-ou 陵王

Text courtesy JAANUS. A type of bugaku mask (bugakumen 舞楽面). Also called Raryouou 羅陵王, Ranryouou 蘭陵王 (King Lanling), and Ryuuou 竜王 (Dragon King). A bugaku 舞楽 dance and the mask (bugakumen 舞楽面) of a golden beast with a dragon perched on its head. Classification (for terms see bugaku 舞楽): a dynamic dance (hashirimai 走舞) of the Left (sa-no-mai 左舞) originally from either Southeast Asia (Rin'yuugaku 林邑楽) or China (Tougaku 唐楽) performed by one person dressed in a fringed tunic and pantaloons (ryoutou shouzoku 裲襠装束). According to some the dance celebrates the victory of Prince Lanling (also known as Changgung 長恭 of Pohai 北斉 (Manchuria) over the Zhou. Legends vary but either the handsome and kind prince donned the gruesome Ryouou mask himself and frightened his enemy into submission, or his father's ghost appeared wearing the mask. Others trace the dance back to Indian sources, either to the play NAGANANDA (Joy of the Serpents) or to images of Eight Dragon Kings (Hachidai ryuuou 八大竜王), especially Shagara 沙羯羅 (Jp: Sakara). Following this tradition, folk festivals in Japan since the 13 century often incorporate the dance of Ryouou as a rain prayer, for dragons are associated with water and the east. This last function may account, in part, for the great popularity of the dance; which dates back to at least to the Heian period. The sharp nose, bulging, rotating eyes (dougan 動眼) and gaping mouth with huge teeth and dangling chin (tsuriago 吊顎) are given a concentrated aggressive intensity by the wrinkles that line the face and the carved strands of heavy hair above the forehead. The gold face and metallic eyes are set off by the green hair and vermillion mouth. Tuffs of animal hair suggestive of eyebrows and moustache add an uncanny realism. On top perches a crouching dragon. The dragons on top are of two kinds. Some, like the one on the late 12c Ryouou at Itsukushima Jinja 厳島神社 appear as separate figures seated on the head, with chest raised and limbs distinct. Many of these were carved separately and then attached to the mask. Other dragons, such as the one on the 13c Ryouou at Tsurugaoka Hachimanguu 鶴岡八幡宮 in Kamakura form an integral part of the mask, like an elaborate crown that is carved simultaneously with the face out of the same block. A dry lacquer (kanshitsu 乾漆) Ryouou at Fujita 藤田 Art Museum in Osaka may well be the only 8c bugaku mask preserved today. Although damaged, it still retains the flavor of (8c) sculpture. Many of the 64 extant old Ryouou masks are preserved in the countryside and were made after the 13c for folk festivals. Most have simplified constructions (eg. no movable eyes) or carving. Some show a patternization and distortion of the original model (Tendaiji 天台寺, Iwate prefecture; Hakusan Jinja 白山神社, Niigata prefecture), while some have added elaborations such as sharp teeth set into the dangling chin (Ooboshi Jinja 大星神社, Aomori prefecture) and metallic embellishments on the dragon (Tesshuuji 鉄舟寺, Shizuoka prefecture). <END JAANUS QUOTES> Text courtesy JAANUS. A type of bugaku mask (bugakumen 舞楽面). Also called Raryouou 羅陵王, Ranryouou 蘭陵王 (King Lanling), and Ryuuou 竜王 (Dragon King). A bugaku 舞楽 dance and the mask (bugakumen 舞楽面) of a golden beast with a dragon perched on its head. Classification (for terms see bugaku 舞楽): a dynamic dance (hashirimai 走舞) of the Left (sa-no-mai 左舞) originally from either Southeast Asia (Rin'yuugaku 林邑楽) or China (Tougaku 唐楽) performed by one person dressed in a fringed tunic and pantaloons (ryoutou shouzoku 裲襠装束). According to some the dance celebrates the victory of Prince Lanling (also known as Changgung 長恭 of Pohai 北斉 (Manchuria) over the Zhou. Legends vary but either the handsome and kind prince donned the gruesome Ryouou mask himself and frightened his enemy into submission, or his father's ghost appeared wearing the mask. Others trace the dance back to Indian sources, either to the play NAGANANDA (Joy of the Serpents) or to images of Eight Dragon Kings (Hachidai ryuuou 八大竜王), especially Shagara 沙羯羅 (Jp: Sakara). Following this tradition, folk festivals in Japan since the 13 century often incorporate the dance of Ryouou as a rain prayer, for dragons are associated with water and the east. This last function may account, in part, for the great popularity of the dance; which dates back to at least to the Heian period. The sharp nose, bulging, rotating eyes (dougan 動眼) and gaping mouth with huge teeth and dangling chin (tsuriago 吊顎) are given a concentrated aggressive intensity by the wrinkles that line the face and the carved strands of heavy hair above the forehead. The gold face and metallic eyes are set off by the green hair and vermillion mouth. Tuffs of animal hair suggestive of eyebrows and moustache add an uncanny realism. On top perches a crouching dragon. The dragons on top are of two kinds. Some, like the one on the late 12c Ryouou at Itsukushima Jinja 厳島神社 appear as separate figures seated on the head, with chest raised and limbs distinct. Many of these were carved separately and then attached to the mask. Other dragons, such as the one on the 13c Ryouou at Tsurugaoka Hachimanguu 鶴岡八幡宮 in Kamakura form an integral part of the mask, like an elaborate crown that is carved simultaneously with the face out of the same block. A dry lacquer (kanshitsu 乾漆) Ryouou at Fujita 藤田 Art Museum in Osaka may well be the only 8c bugaku mask preserved today. Although damaged, it still retains the flavor of (8c) sculpture. Many of the 64 extant old Ryouou masks are preserved in the countryside and were made after the 13c for folk festivals. Most have simplified constructions (eg. no movable eyes) or carving. Some show a patternization and distortion of the original model (Tendaiji 天台寺, Iwate prefecture; Hakusan Jinja 白山神社, Niigata prefecture), while some have added elaborations such as sharp teeth set into the dangling chin (Ooboshi Jinja 大星神社, Aomori prefecture) and metallic embellishments on the dragon (Tesshuuji 鉄舟寺, Shizuoka prefecture). <END JAANUS QUOTES>

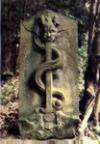

Kurikara 倶利迦羅

Text courtesy JAANUS. Also known as Kurika 矩里迦, a transliteration of Sanskrit ”Kulika,” the name of a dragon-king (see above) mentioned in Indian legends. In this connection he is also known as Kurikara Ryuu 倶利迦羅龍 ("Dragon Kurikara"), sometimes with the addition of ou 王, to read "Dragon King Kurikara." Kurikara could also be an abbreviated transliteration of Kulika raja ("King Kulika"), or of Kulika-nagaraja ("Dragon King Kulika").

In Esoteric Buddhism he is regarded as a manifestation of Fudou Myou-ou 不動明王 and is also known as Kurikara Fudou 倶利迦羅不動 or Kurikara Myou-ou 倶利迦羅明王. He assumes the form of a flame-wreathed snake or dragon coiled around an upright sword, with his open mouth about to swallow the tip of the weapon, which is called the "Kurikara sword" (kurikara-ken 倶利迦羅剣). According to the KURIKARA RYUU DARANIKYOU 倶利迦羅龍王陀羅尼経, this manifestation of Fudou had its origins in a contest between Fudou and a non-Buddhist heretic in the course of which Fudou transformed himself first into a sword and then into the dragon Kurikara and threatened to devour the sword into which the heretic had changed himself. Alternatively the dragon and sword are sometimes said to represent the noose and sword held by Fudou and images of Kurikara may be used as a substitute for Fudou as for example on the lid of a lacquered sutura box from the Heian period belonging to Taimadera 当麻寺 (Nara Prefecture), where he is flanked by Fudou's two attendants Kongara Douji 矜羯羅童子 and Seitaka Douji 制た迦童子. Early statuary representations are rare: that kept at Ryuukouin 龍光院 (Mt. Kouya 高野, Wakayama prefecture) inside a small shrine (zushi 厨子) is thought to date from the Kamakura period, although temple tradition holds that the sword (42.2cm) was brought back to Japan by Kuukai 空海 (774-835 AD). The largest completely wooden image (183.2cm), dating from the late Heian period (11c-12c), is kept at Kotakeji 小武寺, Ooita prefecture. The "Kurikara pattern" (kurikara-monmon 倶利迦羅紋々) is also a popular motif in tattoos (irezumi 入墨). For more on Kurikara Fudou, please see Dr. Gabi Greve’s sites, one and two. In Esoteric Buddhism he is regarded as a manifestation of Fudou Myou-ou 不動明王 and is also known as Kurikara Fudou 倶利迦羅不動 or Kurikara Myou-ou 倶利迦羅明王. He assumes the form of a flame-wreathed snake or dragon coiled around an upright sword, with his open mouth about to swallow the tip of the weapon, which is called the "Kurikara sword" (kurikara-ken 倶利迦羅剣). According to the KURIKARA RYUU DARANIKYOU 倶利迦羅龍王陀羅尼経, this manifestation of Fudou had its origins in a contest between Fudou and a non-Buddhist heretic in the course of which Fudou transformed himself first into a sword and then into the dragon Kurikara and threatened to devour the sword into which the heretic had changed himself. Alternatively the dragon and sword are sometimes said to represent the noose and sword held by Fudou and images of Kurikara may be used as a substitute for Fudou as for example on the lid of a lacquered sutura box from the Heian period belonging to Taimadera 当麻寺 (Nara Prefecture), where he is flanked by Fudou's two attendants Kongara Douji 矜羯羅童子 and Seitaka Douji 制た迦童子. Early statuary representations are rare: that kept at Ryuukouin 龍光院 (Mt. Kouya 高野, Wakayama prefecture) inside a small shrine (zushi 厨子) is thought to date from the Kamakura period, although temple tradition holds that the sword (42.2cm) was brought back to Japan by Kuukai 空海 (774-835 AD). The largest completely wooden image (183.2cm), dating from the late Heian period (11c-12c), is kept at Kotakeji 小武寺, Ooita prefecture. The "Kurikara pattern" (kurikara-monmon 倶利迦羅紋々) is also a popular motif in tattoos (irezumi 入墨). For more on Kurikara Fudou, please see Dr. Gabi Greve’s sites, one and two.

Woodblock by Utagawa Kunisada II, 1860

Courtesy of Ukiyo-eWoodblockPrints.com

LEARN MORE

- Buddhist-Artwork.com.

Dragon statues are available for purchase at our sister site.

- Dragon: One of Four Celestial Emblems of Ancient China

- Shachihoko, Naga, Makara, Makatsu. Serpentine-like sea monster related to the dragon.

- 28 Lunar Mansions and the Dragon

- Dragon in Taiwan

- View Star Charts of the Dragon Constellation (outside site)

- JAANUS. Dragon Origins in China. A special thanks to JAANUS, the Japanese Architecture & Art Net User System, for allowing me to quote above text. A visit to their online dictionary is highly recommended. Over 8000 entries. The photos presented here, however, are not from JAANUS, but rather from my own photos and web crawling.

- A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms. With Sanskrit & English Equivalents. Plus Sanskrit-Pali Index. By William Edward Soothill & Lewis Hodous. Hardcover, 530 pages. Published by Munshirm Manoharlal. Reprinted March 31, 2005. ISBN 8121511453.

- Ghosts, Demons & Spirits in Japan (by Norman A. Rubin)

- Dragons in Art and on the Web (by Tim Spalding). Hundreds of links and photos.

- Dragon Calligraphy by Yamaoka Tesshu (hosted by Gabi Greve)

- Myths and Legends of Japan. Author Frederick Hadland Davis. Courier Dover Publications. 1912 (Republished 1992). ISBN 0486270459, 9780486270456

- Animal Motifs in Asian Art: An Illustrated Guide to Their Meanings and Aesthetics.

Author Katherine M. Ball. Courier Dover Publications, 2004. (First published 1927)

- An Encyclopedia of Myth and Legend: Chinese Mythology. Author Derek Walters. 1993.

- Myths of China and Japan. Author Donald A. Mackenzie. 2005.

Butsuzō-zu-i 仏像図彙, the “Collected Illustrations of Buddhist Images.” Published in 1783 (Genroku 元禄 3). One of Japan’s first major studies of Buddhist iconography. Hundreds of pages and drawings, with deities classified into approximately 80 (eighty) categories. Modern-day reprints are available at this online store (J-site).

- A History of Japanese Religion. Edited by Kazuo Kasahara. Kosei Publishing Company, 2002. Translated by Paul McCarthy and Gaynor Sekimori. 648 pages. Sixteen distinguished experts on Japanese religion approach the topic from modern perspectives. Topics range from prehistoric times up until the early postwar years. Click here to read review of book by scholar Paul L. Swanson.

- Buddhism: Flammarion Iconographic Guides, by Louis Frederic, Printed in France, ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995. A highly illustrated volume, with special significance to those studying Japanese Buddhist iconography. Includes many of the myths and legends of mainland Asia as well, but its special strength is in its coverage of the Japanese tradition. Hundreds of accompanying images/photos, both B&W and color. A useful addition to your research bookshelf.

- UNCONFIRMED RESEARCH. Hoshi-no-tama (star ball). In Japanese artwork, dragons are sometimes depicted with a pearl or ball under its chin. Those who obtain it can force the dragon to help them. One theory says that the dragon "reserves" some of its magic in this ball when it shape shifts.

ū ā ō Ō

|

|