To work officially as a priest in modern Japan, individuals must pass examinations given by the Association of Shintō Shrines (Jinja Honchō 神社本庁) -- these tests are open to both men and women who want to become Shintō priests. But until modern times, there was no standardized certification or qualification system. Throughout most of Japan’s recorded history, appointments to the priesthood were controlled by the imperial court, priestly family lineages (e.g., Arakida 荒木田, Ōmiwa 大神, Ōnakatomi 大中臣, Watarai 度会, Yoshida 吉田), and various Shintō schools (e.g. Yoshida Shintō 吉田神道). Essentially, the Shintō priesthood was a hereditary profession -- passed along from father to son -- until the Meiji Era (1868-1912). On 14 May 1871, the Meiji government issued orders abolishing the hereditary system and private ownership of shrines. Theoretically, these ordinances should have eradicated the hereditary system, but in practice, priests were still able to inherit their positions by applying for and receiving the approval of authorities. <sourcesREFERENCES:

The order abolishing the hereditary Shinto priesthood and private ownership of shrines was issued on 14 May 1871. See documents listed below:

- Fukoku Zensho (A Compendium of Proclamations), Vol. 5, Gaishi Kyoku (Tokyo), 1871.

- Daijoukan Fukoku (Council of State Proclamations), No. 234, pp. 21-22.

- Sakamoto Kenichi, ed., Meiji Ikou Jinja Kankei Hourei Shiryou (Materials for a History of Shrine-related Laws and Ordinances, beginning with the Meiji Era), Heibonsha (Tokyo), 1968, pp. 29-30.

- For Japanese spellings of above documents, see RESOURCES.

- Fridell, Wilbur. M. The Establishment of Shrine Shinto in Meiji Japan. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 2 / 2-3 June-September 1975. This article explores the bureaucracy controlling State Shinto and priestly rank/status based on the type of shrine one worked at.

>

The Jinja Honchō was established in February 1946, when Shintō shrines were legally separated from the state and forced to re-organize as non-governmental entities. Today the bulk of all Shintō shrines (some 80,000 out of 90,000) belong to the Jinja Honchō. Says the Ueno Tenmangu Shrine (Nagoya): “To become a Shintō priest of a shrine one now has to belong to a shrine and pass an examination set by the Jinja Honchō. In order to produce priests of the required high level the study courses are that much higher, especially when compared with former times. Of course there are differences in the courses, depending on the rank you wish to attain. The ranks are jōkai 浄階, meikai 明階, seikai 正階, gonseikai 権正階, and chokkai 直階 (see list below). As an example, for the rank of meikai, trainees take a total of twenty-six compulsory subjects, including twelve related to Shintō, six related to general religion, and eight subjects on general education. Nationwide, there are only two professional institutions which have Shintō departments for the training of Shintō priests, Kokugakuin University in Tokyo 國學院大學 and Kōkagakkan University in Ise 皇學館大學. Some of the larger shrines have their own training facilities, and the Prefectural Shrine Office of Osaka is unique in that it has a correspondence course. <end quote from Ueno Tenmangu Shrine>

Ranks Based on Exams (High to Low)

Ranks Based on Exams (High to Low)

- Jōkai 浄階; highest rank; awarded to those who have contributed greatly over many years to Shintō studies and practice.

- Meikai 明階; qualification required to serve as head priest (Gūji 宮司) or assistant priest (Gongūji 権宮司) at most shrines nationwide -- excludes the role of chief priest (Daigūji 大宮司) at Ise Jingū Shrine 伊勢神宮.

- Seikai 正階; qualification required to serve as head priest (Gūji 宮司) at prefecture-level shrines or as a lower-ranked priest (Negi 禰宜) at most shrines nationwide.

- Gonseikai 権正階; qualification required to serve shrines at the village and township level; those at this rank still unable to serve at prefecture-level shrines.

- Chokkai 直階; entry level rank.

NOTE: Kōkagakkan & Kokugakuin are non-discriminatory in awarding accreditation to either men or women seeking to become Shintō priests. Some other training centers (e.g., Kurozumi-kyō 黒住教) also train women to become priests. Nonetheless, there are few female shrine priests. A Year in the Life of a Shinto Shrine (1996), by John K. Nelson, includes an interview with one.

Job Titles at Most Shrines (High to Low)

- Gūji 宮司; chief priest; at some shrines, it is necessary for the Gūji to attain the qualification of at least Gonseikai and/or Meikai

- Gongūji 権宮司; assistant priest or deputy priest

- Negi 禰宜; lower-rank priest

- Gonnegi 権禰宜; assistant to lower-rank priest

Job Titles at Ise Jingū Shrine 伊勢神宮

Ise Jingū 伊勢神宮. The Grand Shrine of Ise (or Ise Shrine) in Mie Prefecture continues to play a pivotal role in modern-day Shintōism. It and its numerous sub-shrines are devoted to Amaterasu Ōmikami 天照大神 (female, sun goddess, chief deity of Ise's inner sanctuary or Naikū 内宮, chief of all Shintō kami) and Toyo-uke Ōmikami 豊受大御神 (male, god of agriculture and industry, chief deity of Ise's outer sanctuary or Gekū 外宮). The high priest and high priestess of Ise Shrine are typically members or descendants of Japan’s imperial family. The worship of Amaterasu is of particular importance, for Japan’s imperial family claims direct descent from her divine lineage. Ise Shrine is arguably one of Japan’s most important Shintō enclaves and one of the nation’s oldest. See Kōshitsu Shintō (State Shintō) for more on Ise Shintō 伊勢神道. Given its exalted status among nationwide shrines, Ise Jingū has a priestly class that is somewhat different from the norm.

- Saishu 祭主; highest rank, master of religious ceremonies

- Daigūji 大宮司; chief priest or high priest

- Shōgūji 少宮司; assistant priests

- Negi 禰宜; lower-rank priests

- Gonnegi 権禰宜; assistants or deputies of lower-rank priests

- Gūshō 宮掌; shrine administrators

Miko 巫女 -- Priestess, Female Shaman,

Miko 巫女 -- Priestess, Female Shaman,

Shrine Maiden, Women AttendantMiko, written variously as 巫子, 神子, 御子, 巫祝, or 巫女 (sometimes read as “Fujo”). Miko have traditionally served as shamans, spirit mediums, shrine virgins, shrine maidens, and ritual dancers. They have long been involved in religious duties at shrines or acted as individuals without any shrine affiliation (the latter type were/are commonly associated with a specific village or travel around the countryside performing magic). In the past, they also helped to organize pilgrimages, provided religious entertainment (e.g.,

kagura 神楽 dancing, miko mai 巫女舞 dancing), and assisted in ritual prayers (kitō 祈祷, lit. “invocations of divine power”). They were frequently unmarried virgins who served as vehicles for divine revelations (takusen 託宣) from the kami or in transmitting the words of the dead.

In general, there are no special qualifications or certifications required in modern times to become a miko. Their role in contemporary Shintō has been much depreciated -- their main tasks today are mostly to assist the male priests, clean the shrine compound, sell amulets at the shrine shop, perform dances, and assist in shrine rituals and prayers. Women can train to become shrine priests, but few women elect this path. In the Buddhist camp, women who serve their faith are called Bikuni 比丘尼. This is most commonly translated as "Buddhist nun," one who was ordained with the ten novice precepts (shami no jikkai 沙彌十戒). But in modern Japan, it also refers to Sōtō Zen nuns who were ordained by taking the ten Bodhisattva precepts (bosatsu jikkai 菩薩十戒). Zen nuns in Japan today comprise less than one percent (250) of the total ordained Zen clergy (approx 25,000). <source:

DDB; sign in = guest> Many of these women were married and had children before they took their vows.

|

Modern Female Shintō Priest.

Uetsuki Hachiman Jinja Shrine

植槻八幡神社 in Nara.

Named Saitō Rika 齋藤梨歌,

she claims to be the first modern

woman head priestess (gūji)

from a non-Shintō household.

Photo by John Dougill.

Miko dancing kagura 神楽

|

|

Number of Female Priests Compared to Male Clergy.

Number of Female Priests Compared to Male Clergy. Although statistics are hard to come by,

Kokugakuin Univ. says the number of female priests (1,825 registered females in 1993) was slightly less than 10% of all priests in the category of Shrine Shintō (

Jinja Shintō 神社神道). <

note

NOTE:

The number of female priests (at the end of June 2010), says Mr. Iwahashi Katsuji of the Jinja Honcho, was 2,995. "This number does not include females who have a licence to work as a priest but are not working for shrines. In other words, this number indicates only working priests. The most recent statistics will be released to the public in October." Unfortunately, Iwahashi-san did not give me the corresponding number for all shrine priests, which would allow us to determine if female priests are increasing as a percentage of all priests. But the answer is most likely "yes," that percentage is increasing.

> This is extremely low compared to rates found among shrines belonging to Sectarian Shintō (

Kyōha Shintō 教派神道) and the

New Religions (Shinkō Shintō 新興神道).

See Kokugakuin’s Rates of Women in Shintō Clergy. For comparative purposes, in 2006, some 79,000 Shintō clergy attended to their congregations compared to 314,000 Buddhist clergy. <source

Cultural Affairs Dept., Agency for Cultural Affairs>

“What is striking about female numbers,” says author

John Dougill, “is that virtually all of that 10% come from Shintō households or are/were women married to priests. World War II apparently gave a boost to female priests, with wives and daughters replacing the missing menfolk.” <end quote> Say the authors of the

Japan in the 21st Century (page 72): “According to the Association of Shinto Shrines, there were 25 women among the 404 head priests in Tokyo in 2001. Before World War II, it was virtually unheard of for a Shinto priest to be a woman; the priesthood was usually passed from father to son. But with the lack of interest in religion, and with families growing smaller, shrine priesthoods have had to open up to daughters, to keep the priesthood in the family.”

Miko in Modern Japan. Says

Japan in the 21st Century (page 72): “There are female Shinto priests, but they are much less common than female miko. There are no figures to show how many miko work at Japan's 80,000 shrines. Although about twenty women graduate from

Kokugakuin University as priestesses every year, only one or two actually get jobs, mainly because of the perception that men are more suited to the position. Some miko are high school girls serving part-time when things get busy at the shrines. Others work as miko as a profession for a longer time, but usually not for a whole lifetime. At one of the most important shrines in Ise, Mie Prefecture, miko are called

maijo 舞女, or dancing girls, and their main job is to dance and offer prayers and offerings. Part of the appeal for the job seems to be the chance to experience traditional Japanese culture, including dance, tea ceremony, and flower arranging. At Yushima Shrine in Tokyo's Bunkyo-ku, miko dance at weddings and ceremonies and sell amulets, including a matched set of a headband, a charm, and pencils, to eager students. There is an inner sanctum that is off limits to women, but the miko clean all the rest of the shrine and the offices as well.” <end quote>

Miko and Shamanic Shintō. Shamanic

Shintō involves female shamans called MIKO. It is a branch of understanding outside Western scientific paradigms that existed well before the

introduction of Buddhism to Japan. In various locations still today, female shamans help grieving parents contact their departed children in the neitherworld (

Sainokawara), and in some localities, they perform cures and organize religious ceremonies

. In northeastern Japan, blind female shamans are known as

Itako イタコ. Shamanic Shintō is also closely associated with belief in animal spirits (e.g., snake,

fox, wolf, dog,

monkey,

kappa). Says the

Kokugakuin University Encyclopedia of Shinto: "MIKO. A general term for a woman possessing the magico-religious power to receive oracles (takusen 託宣) from the kami in a state of spirit possession (kamigakari 神懸 or 神憑). Nowadays the term generally refers to a woman who assists shrine priests in ritual or clerical work.............Eventually, however, male

kannushi,

hafuri, and

negi took their place, and Miko came to be placed in roles assisting these male ritualists, according to one theory." See complete

Miko entry here. For a 122-page report on Shamanism in Japan, see story by William P. Fairchild from Folklore Studies XXI, 1962. Also see another report by Fairchild entitled

Necromancers in the Tōhoku (Folklore Studies XXI, 1962), as well as

Shamanism in Japan, by Hori Ichirō, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 2/4 December 1975.

Ceremony at Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine in Kamakura; Shrine Priest and female Miko attendants

Modern Female Shintō Priest leading festival at Hakone Jinja 箱根神社

Kanagawa Prefecture, near Mt. Fuji. See Dougill’s review here.

Other Important Terms for Those Serving Shintō Shrines

- Hafuri 祝. A term for Shintō priests, usually a rank beneath kannushi and negi. (Kokugakuin)

- Hafuribe 祝部. One type of priest established under the ancient ritsuryō system. (Kokugakuin)

- Kandachi 神館; place for Shintō purification rites, as well as a place for priests to go into seclusion for a set amount of time; also known as Saikan 斎館 or Shinkan 神館.

- Kannushi 神主; generic term for shrine priests and those who perform religious duties at Shintō shrines; also known as Saikan 斎館 or Shinshoku 神職. Says the Kokugakuin University Encyclopedia of Shintō: "The kannushi was a mediator (nakatorimachi 仲執り持ち or 仲取持ち) between kami and humans, and served the kami on behalf of humanity. Sometimes the kannushi played the role of the kami or even acted as a kami to transmit the will of the kami to humanity."

- Nai-Shōten 内掌典. Female attendants who assist the emperor in the performance of the annual Niinamesai ceremony 新嘗祭 (rice tasting ceremony), when the emperor offers the first fruits of each year's rice harvest to the gods and then eats a little himself.

- Saikan 斎館; one who performs religious duties at Shintō shrines; aka Kannushi 神主 or Shinshoku 神職. Saikan also refers to a purification hall where priests purify themselves prior to participating in ceremonies. At Ise Jingū, the head priestess as well undergoes purification in the Saikan.

- Shashi 社司. One who performs religious duties at higher ranking Shintō shrines.

- Shashō 社掌. Deputy priest, one rank below Shashi.

- Shikan 祠官. Priest at low-level village and hamlet shrines; those serving so-called “people’s shrines” (Minsha 民社)

- Shinkan 神館; see entry for Kandachi.

- Shinkan 神官; general term for Shintō priest.

- Shinshoku 神職; performs religious duties at Shintō shrines; aka Kannushi 神主 or Saikan 斎館.

- Shishō 祠掌. Priest at low-level village and hamlet shrines; those serving so-called “people’s shrines” (Minsha 民社)

- Shōten 掌典. Male clergy who assist the emperor in the performance of the annual Niinamesai ceremony 新嘗祭 (rice tasting ceremony).

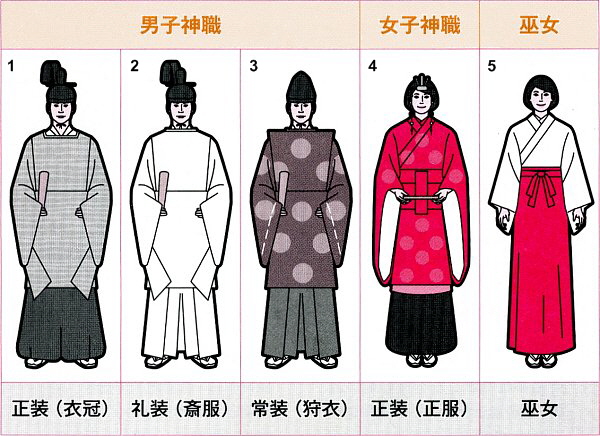

Shintō Attire Among Clergy

The robes worn today by Shintō priests and priestesses are reportedly derived from gowns worn by the court and nobility in the Heian period (794 to 1185). <source: Book of Shintō 神道の本 by Mitsuhashi Takeshi 三橋健, Dec. 2010, p. 84.>

Above chart from Book of Shintō 神道の本 by Mitsuhashi Takeshi 三橋健, Dec. 2010, p. 85.

- Seisō 正装 (Ikan 衣冠); formal attire, ceremonial attire; used for state or imperial functions

- Reisō 礼装 (Saifuku 斎服); white attire for Shintō purification rituals, ablutions and festival events; white represents purity (or lack of impurity), and is thus the most commonly worn color by shrine personnel. However, different colors are allowed during various religious ceremonies (see examples in above chart). In the Edo period, shrine personnel without rank were required (by shogunate ordinance) to wear “kariginu 狩衣 robes made of white cloth (hakuchō 白張); other apparel may only be worn after obtaining a permit from the Yoshida family.” <source: Shosha Negi Kannushi Hatto 諸社禰宜神主法度 entry at Kokugakuin Encyclopedia of Shintō).

- Tsunesō 常装 (Kariginu 狩衣); normal attire for Shintō ceremonies; buy outfit online.

- Seisō 正装 (Seifuku 正服); formal attire worn by female shrine maidens.

- Miko Attire; most commonly worn outfit of female shrine maidens; buy outfit online.

Shintō Priests at Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine in Kamakura

LEARN MORE

Explore the numerous external links in above story. They are specified by the  icon.

icon.

- How to Become a Shinto Priest || Kokugakuin Univ. History || Kōgakkan Univ. History

- Kōkagakkan University in Ise 皇學館大學 (official J-site)

- Kokugakuin University in Tokyo 國學院大學 (official E-site)

- Shinto Studies at Kakugakuin University (official J-site)

- So You Want to Become a Shinto Priest - Shintoism.livejournal.com

- Become a Shinto Priest -- Wikihow.com

- Center for Shinto Studies and Japanese Culture || Members of the Center

- Priestesses in Shinto (from Nihonbunka.com)

- Miko (Shrine Females) -- from the Kokugakuin University Encyclopedia of Shinto

- Fairchild, William P, Shamanism in Japan (Folklore Studies XXI, 1962). Also see another Fairchild report entitled Necromancers in the Tōhoku (Folklore Studies XXI, 1962).

- Fridell, Wilbur. M. The Establishment of Shrine Shinto in Meiji Japan. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 2 / 2-3 June-September 1975. This article explores the shrine office in the bureaucracy and priestly rank and status.

- Hori Ichirō, Shamanism in Japan, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 2/4 December 1975.

- The order abolishing the hereditary Shintō priesthood and private ownership of shrines was issued on 14 May 1871. See, for example:

- Fukoku Zensho 布告全書 (Compendium of Proclamations), Volume 5,

Gaishi Kyoku (Tokyo), 1871

- Daijōkan Fukoku 太政官布告 (Council of State Proclamations), No. 234, pp. 21-22

- Sakamoto Kenichi 坂本健一, ed., Meiji Ikō Jinja Kankei Hōrei Shiryō 明治以降神社関係法令資料 (Materials for a History of Shrine-related Laws and Ordinances, beginning with the Meiji Era), Heibonsha (Tokyo), 1968, pp. 29-30.

- Shosha Negi Kannushi Hatto 諸社禰宜神主法度. “An ordinance aimed at all shrines and shrine affiliated priests, pronounced as part of the religion control policy of the Edo Shogunate. In Edo period, Shrine personnel without rank shall wear "kariginu robes made of white cloth" (hakuchō). Other apparel may only be worn after obtaining a permit from the Yoshida family." (Kokugakuin)

- Meiji Period Chronology (Shikokuhenrotrail.com); describes the various laws issued by the reformist Meiji government, including laws controlling both the Shintō and Buddhist priesthood.

- Japanese Historical Text Initiative (Univ. of California Berkeley) -- search old texts

- Shintō Terminology from Yahoo Japan

|

SPECIAL THANKS. This page owes a big debt of thanks to John Dougill, a longtime resident of Japan and the author of numerous books, including Kyoto: A Cultural History (Cityscapes), published in 2006. He generously shared his knowledge of Shintō, his Shintō contacts, his critical writer’s eye, and various photos. Dougill, now operating out of Kyoto, is currently focused on Green Shinto, a blog dedicated to the promotion of an open, international, and environmental Shintō. The site also includes interviews with various people involved with Japan’s religious scene, including various shrine priests (both Japanese and non-Japanese). See his interviews with Rica Saito, Pat Ormsby, Caitlin Stronell, Rev. Barrish, and others. SPECIAL THANKS. This page owes a big debt of thanks to John Dougill, a longtime resident of Japan and the author of numerous books, including Kyoto: A Cultural History (Cityscapes), published in 2006. He generously shared his knowledge of Shintō, his Shintō contacts, his critical writer’s eye, and various photos. Dougill, now operating out of Kyoto, is currently focused on Green Shinto, a blog dedicated to the promotion of an open, international, and environmental Shintō. The site also includes interviews with various people involved with Japan’s religious scene, including various shrine priests (both Japanese and non-Japanese). See his interviews with Rica Saito, Pat Ormsby, Caitlin Stronell, Rev. Barrish, and others.

|

|