|

|

|

|

Hachi Bushū (Hachibushu, Hachibushuu) 八部衆

Eight Legions, Eight Deva Guardians of Buddhism

Also called Ninpinin 人非人 = Lit. Human & Non-Human

Also called Tenryū Kijin 天龍鬼神 = Deva, Naga, Demons, Gods

Also Tenryū Hachibushū 天竜八部衆 = Deva, Naga, Others Members of Eight Classes

Members of the TENBU, Members of the 28 LEGIONS

Origin: India & Hindu Mythology

|

The Eight Legions are a curious grouping of Buddhist protectors, demons, and spirits. Among the eight groups, only the Ten (Skt. Deva) and Ryū (Skt. Naga; serpent-like creatures, including Dragons) appear with great frequency in Japanese sculpture and artwork, while the other six are represented much less so. As a group, the Hachi Bushu are not objects of Buddhist worship, although some individual Ten (Deva) are given independent status as objects of devotion (e.g., Bishamonten, Benzaiten, Daikokuten).

|

- Ten (Skt: Deva). Celestial beings, 6th level of existence

- Ryū (Ryu, Ryuu) (Skt: Naga). Serpent-like creatures, including dragons. Attendants to Kōmokuten (Shitennō)

- Yasha (Skt: Yaksa). Warriors of Fierce Stance, Nature Spirits.

Protect Yakushi Nyorai, commanded by Tamonten (Shitennō)

- Kendatsuba (Skt: Gandharva). Gods of music, medicine, children. Commanded by Jikokuten (Shitennō); one of their kings is Sendan Kendatsuba

- Ashura (Skt: Asura). Demigod, 4th level of existence

- Karura (Skt: Garuda) Bird-man, enemy of dragons

- Kinnara (Skt: Kimnara). Celestial musicians & dancers; human form with horse’s head; commanded by Tamonten (Shitennō)

- Magoraka (Skt: Mahoraga). Serpentine musicians

|

|

HISTORICAL NOTES: The Hachi Bushū (Eight Legions) are eight groups of sentient and supernatural beings said to be present when Shaka Nyorai (Historical Buddha) expounded the Flower Sutra on Vultures Peak (also called Eagle Peak). They originated in earlier Hindu mythology, but converted to Buddhism after listening to the words of Shaka Nyorai, thereafter becoming guardians of Buddhist teachings. Two of the eight -- the Ashura (Demigods) and Ten (Deva) -- also populate two of the six states of existence. The lowest three states are called the three evil paths, or three bad states. They are (1) people in hells; (2) hungry ghosts; (3) animals. The highest three states are (4) Asura; (5) Humans; (6) Deva. All beings in these six states are doomed to death and rebirth in a recurring cycle over countless ages -- unless they can break free from desire, from the cycle of suffering (Skt. = Samsara). HISTORICAL NOTES: The Hachi Bushū (Eight Legions) are eight groups of sentient and supernatural beings said to be present when Shaka Nyorai (Historical Buddha) expounded the Flower Sutra on Vultures Peak (also called Eagle Peak). They originated in earlier Hindu mythology, but converted to Buddhism after listening to the words of Shaka Nyorai, thereafter becoming guardians of Buddhist teachings. Two of the eight -- the Ashura (Demigods) and Ten (Deva) -- also populate two of the six states of existence. The lowest three states are called the three evil paths, or three bad states. They are (1) people in hells; (2) hungry ghosts; (3) animals. The highest three states are (4) Asura; (5) Humans; (6) Deva. All beings in these six states are doomed to death and rebirth in a recurring cycle over countless ages -- unless they can break free from desire, from the cycle of suffering (Skt. = Samsara).

SAYS JAANUS: Hachibushuu is an abbreviation of Tenryuu Hachibushuu 天竜八部衆. Eight classes of Indian deities who were converted by Shaka (Historical Buddha) and came to be considered protectors of the Dharma (Buddhist Law). They appear in many texts, including the HOKEKYOU 法華経 (Lotus Sutra), and are named as follows: Ten 天 (Deva), Ryuu 龍 (Naga), Yasha 夜叉 (Yaksa), Kendatsuba 乾闥婆 (Gandharva), Ashura 阿修羅 (Asura), Karura 迦楼羅 (Garuda), Kinnara 緊那羅 (Kimnara), and Magoraka 摩ご羅伽 (Mahoraga). The names are not fixed, and an individual deity may sometimes represent their class. The most famous set in Japan was made of dry lacquer in 734 AD and once accompanied an image of Shaka Buddha. There is also a set of sculptures of Shaka's disciples in Koufukuji 興福寺 (Nara). Temple tradition gives their names as Gobujou 五部浄 for the Ten, Shagara (or Sakara) 沙羯羅 for the Ryuu, Kubanda 鳩槃荼 for the Yasha, Kendatsuba, Ashura, Kinnara, and Hibakara 畢婆迦羅, probably for the Magoraka. The Hachibushuu usually appear amidst groups, such as the group of figures surrounding Shaka in paintings of his death (Nehan-zu 涅槃図). They were shown as a distinct group only in the Nara period. <end JAANUS quote>

The eight are discussed below. Links to their individual pages (when available) are also provided. These are the main group of eight most often mentioned in Chinese and Japanese Buddhist texts. There is another grouping of eight that included men (but excluded the Kendatsuba), but this latter grouping is rare.

|

RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE

|

|

TEN 天

TENBU 天部

Skt. = Deva

At Kofuku-ji in Nara, the Tenbu are represented by: 五部浄 Gobujō

Photo: Tamonten (aka Bishamonten), one of the most popular Tenbu in Japan; Heian Period, Kurama Dera, Kyoto

Member of the

28 Legions (Nijūhachi Bushū)

|

Ten or Tenbu is the Japanese term for Deva. The Deva (meaning “celestial beings”) rank above the Asura and humans in the six stages of existence. Many devas have godlike powers, and reign over celestial kingdoms of happiness and splendor. Deva live countless years, but their lives eventually end, for the Deva are not yet free from the cycle of birth and death (the Six States). That distinction belongs only to the Bosatsu, the Rakan, and Nyorai (Buddha). Among the Eight Legions, the Deva are represented most often by Bonten, Taishakuten, the four Shitennō (especially Bishamonten), and the Goddess Benzaiten. Ten or Tenbu is the Japanese term for Deva. The Deva (meaning “celestial beings”) rank above the Asura and humans in the six stages of existence. Many devas have godlike powers, and reign over celestial kingdoms of happiness and splendor. Deva live countless years, but their lives eventually end, for the Deva are not yet free from the cycle of birth and death (the Six States). That distinction belongs only to the Bosatsu, the Rakan, and Nyorai (Buddha). Among the Eight Legions, the Deva are represented most often by Bonten, Taishakuten, the four Shitennō (especially Bishamonten), and the Goddess Benzaiten.

The Tenbu are not Buddhist saviors, but rather spiritual beings high up on the ladder of enlightenment, above humans, but below the Bosatsu and Nyorai. They are revered as gods and goddesses in Japanese Buddhism, but they are always considered spiritually inferior to the Bosatsu and Nyorai.

See Tenbu and Juniten for detailed listings of the many protector deities in the Tenbu grouping. The Tenbu are heavily represented in the Nichiren sect, and appear frequently in mandalas. .

|

|

RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE

|

|

Ryū 竜

Skt. = Naga

At Kofuku-ji in Nara, the Naga are represented by Shakara 沙羯羅

(しゃがら)

See Dragon Page for many more details.

|

The NAGA are a group of serpent-like creatures described in pre-Buddhist and early Indian Buddhist texts as “water spirits with human shapes wearing a crown of serpents on their heads.” Their mortal enemy is the bird-man Karura and the Phoenix. As protectors of Buddhism, the Naga are attendants to Kōmokuten. In China and Japan, the Dragon incorporates Naga iconography & supplants the Naga. Says M.W. De Visser in Dragon in China and Japan (ISBN 0-7661-5839-X): “According to Northern Buddhism, Nagarjuna (approx. 150 AD), the founder of the Mahayana doctrine, was instructed by Nagas in the sea, who showed him unknown books and gave him his most important work, the Prajna Paramita, with which he returned to India. For this reason his name, originally Arjuna, was changed to Nagarjuna, and he is represented in art with seven Nagas over his head. The Mahayana school knows a long list of Naga kings, among whom the eight so-called Great Naga Kings are the following (given in Sanskrit): The NAGA are a group of serpent-like creatures described in pre-Buddhist and early Indian Buddhist texts as “water spirits with human shapes wearing a crown of serpents on their heads.” Their mortal enemy is the bird-man Karura and the Phoenix. As protectors of Buddhism, the Naga are attendants to Kōmokuten. In China and Japan, the Dragon incorporates Naga iconography & supplants the Naga. Says M.W. De Visser in Dragon in China and Japan (ISBN 0-7661-5839-X): “According to Northern Buddhism, Nagarjuna (approx. 150 AD), the founder of the Mahayana doctrine, was instructed by Nagas in the sea, who showed him unknown books and gave him his most important work, the Prajna Paramita, with which he returned to India. For this reason his name, originally Arjuna, was changed to Nagarjuna, and he is represented in art with seven Nagas over his head. The Mahayana school knows a long list of Naga kings, among whom the eight so-called Great Naga Kings are the following (given in Sanskrit):

- Nanda (called Nagaraja, King of the Naga)

- Upananda

- Sagara (Jp. = Shakara 沙羯羅)

- Vasuki

- Takshaka

- Balavan

- Anavatapta

- Utpala

These eight are often mentioned in Chinese and Japanese legends as the Eight Dragon Kings (八龍王 Hachi Ryū-ō), and were said to have been among Buddha’s audience, with their retinues, while he delivered the instructions contained in the Sutra of the Lotus of the Good Law (Saddharma Pundarika Sutra, Jp. = Hokekyo 法華経, English = Lotus Sutra).” <end quote from Visser, who cited numerous other works in the above passage. >

In China, however, dragon lore (read “naga lore”) existed independently for centuries before the introduction of Buddhism. Bronze and jade pieces from the Shang and Zhou dynasties (16th - 9th centuries BC) depict dragon-like creatures. By at least the 2nd century BC, images of the dragon are found painted frequently on tomb walls to dispel evil. In this role, the dragon was often portrayed as one of the four celestial emblems of China, the one protecting the eastern compass direction. Buddhism was introduced to China sometime in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, and over time the Chinese identified the serpent-like Naga with their own four-legged dragon. By the 9th century AD, the Chinese had incorporated the dragon into Buddhist thought and iconography as a protector of the various Buddha and the Buddhist law. Japan's dragon lore comes predominantly from China. See Dragon page for many more details.

|

|

RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE

|

|

Yasha 夜叉

Skt. = Yaksha

12 Yasha Warriors are typically shown protecting Yakushi Nyorai, the Medicine Buddha.

鳩槃荼 (くはんだ)

薛茘多 (へいれいた)

|

Warriors of fierce stance, these protectors of Buddha’s teachings are the guardian spirits of nature. In earliest Hindu records, they converted to Buddhism after listening to the Historical Buddha present his teachings at Vultures Peak. In the Mahabharatha text of India, Yama, the Lord of the Dead, assumes the form of a Yaksha to question his son. Warriors of fierce stance, these protectors of Buddha’s teachings are the guardian spirits of nature. In earliest Hindu records, they converted to Buddhism after listening to the Historical Buddha present his teachings at Vultures Peak. In the Mahabharatha text of India, Yama, the Lord of the Dead, assumes the form of a Yaksha to question his son.

In their earliest Hindu manifestations, the Yaksha were spirits of the trees, forests, and villages. They can be both benign or demonic (when portrayed as demonic, they are flesh-eating demons that are sometimes called the Raksha (J = Rasetsu). The Rasetsu, moreover, might be particularly monstrous Yaksha, or alternatively, the Yaksha may be Rasetsu who have pledged to serve the Deva as guardians of forests and villages. There does not appear to be any clear iconography. When acting as protectors of Buddhism, the Yaksha are soldiers in the army of Tamonten, one of the Four Heavenly Kings. They are also protectors of the Yakushi Nyorai (Buddha of Healing and Medicine).

Kubera: Hindu God of Wealth. Yaksha are powerful earth deities. They guard the world's wealth, such as gold and silver. Kubera (Kuvera), the god of wealth and buried treasure, is sometimes considered the king of the Yaksha. Says Meher McArthur, the curator of East Asian Art, Pacific Asia Museum (Pasadena):

“In Tibet and Nepal, Vaishravana (Jp. = Bishamonten / Tamonten) is closely related to the God of Wealth, Kubera, who is considered to be his most important manifestation. It is possible that Vaishravana is the Buddhist form of the earlier Hindu deity, Kubera (Kuvera), who was the son of an Indian sage, Vishrava, hence the name, Vaishravana. According to Hindu legend, Kubera performed austerities for a thousand years, and was rewarded for this by the greator god, Brahma (Jp. = Bonten), who granted him immortality and the position of God of Wealth, and guardian of the treasures of the earth. As Vaishravana, this deity also commands the army of eight Yasha (Jp. = Yaksa), or demons, who are believed to be emanations of Vaishravana himself. The most important of these eight are the dark-skinned Kubera (Kuvera) of the north and the white Jambala of the east. Each of these emanations holds a mongoose that spews jewels. In Tibet and Nepal, he is worshipped as the God of Wealth in all three manifestations: Vaishravana, Kubera, and Jambala. In many Tibetan and Nepalese images of Kubera, the deity is shown as a plump figure wearing a crown, ribbons and jewelry, and holding a mongoose, representing this god’s victory over the naga (snake deities), who symbolize greed. As God of Wealth, Vaishravana/Kubera squeezes the mongoose and causes the creature to spew out jewels.” < quoted from McArthur’s book “Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs & Symbols.” ISBN 0-500-28428-8, Published 2002 by Thames & Hudson. Click here to view or buy book at Amazon. >

Yasha are mentioned in various sutras, yet there seems to be no definitive representation. Some texts say the Yasha are able to fly/move through space; in Java they are portrayed as sturdy, smallish human beings with unusually large canine teeth.

In Japan, the Yaksha serve both Tamonten (aka Bishamonten) and Yakushi Nyorai (the Medicine Buddha), but in artwork they are mostly shown as protectors of the Yakushi Nyoraii. In Japan, there is also the tiny creature called the JYAKI, who appears most frequently beneath the feet of the Shitenno. The Jyaki are classified as a type of Yaksha by the Japanese. In addition, Kariteimo is one of Japan's most widely known Yaksha. She originally was a child-devouring Yakṣa 夜叉 from Hindu lore named Hāritī, but she repents and coverts to Buddhism, and is now a protector of children and the goddess of easy delivery. She had Ten Demon Daughters (Jūrasetsu-nyo 十羅刹女) who aided her in her evil past, and they too ultimately became protectors of Buddhism. These latter ten are classified as Rasetsu 羅刹 (Skt. = Rākṣasīs), who torture & feed upon the flesh of the dead (those who were evil while living). The Rasetsu became guardian deities once introduced to Buddhism; they are listed in the Lotus Sutra.

|

|

RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE

|

|

Kendatsuba 乾闥婆

Skt. = Gandharva

Members of the 8 Legions

protecting Buddhism, the 28 Legions who serve Senju Kannon, and one of 33 manifestations of Kannon

|

|

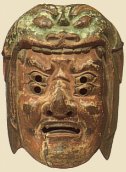

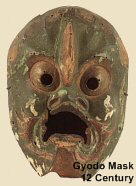

Kendatsuba

12th Century

Gyōdōmen Mask

Hōryū-ji Temple

Sendan Kendatsuba

Hekija 辟邪絵 (exorcist

scroll) of the 12th century

|

|

In early Indian (Vedic) mythology, Kendatsuba was a protector serving Soma and musicians in the paradise of the Hindu god Indra. Later, as Buddhism developed. the Kendatsuba become musicians in the heavenly court of Taishakuten and protectors of Buddhist teachings, as well as deities of medicine, and guardians of children. In paintings, they are sometimes depicted sitting in royal ease surrounded by the twelve animals of the yearly Zodiac cycle. Sometimes shown with halo; said to nourish themselves on scents. The Kendatsuba are attendants to and commanded by Jikokuten (Shitennō).

In Japan, Sendan Kendatsuba 栴檀乾闥婆, a king among the Kendatsuba, is known as a protector of children. He is the central figure in the Dōjikyō Mandara 童子経曼荼羅 of Esoteric Buddhism, which is used in esoteric rituals to protect children from sickness and danger.

Says JAANUS: Kendatsuba is a transliteration of the Sanskrit Gandharva, translated as Jikikou 食香 (scent-eater ), Jinkou 尋香 (scent-seeker), and also known as Koujin 香神 (scent god). A class of semi-divine beings that feed on the fragrance of herbs. In later Indian mythology they are regarded as celestial musicians, in which role they were incorporated into Buddhism as attendants of Taishakuten 帝釈天, who is a protector of Buddhist law. They are also counted among the attendants of Jikokuten 持国天, the guardian king of the eastern direction. They are among the eight classes of beings that protect Buddhism (Hachibushuu 八部衆), and among the twenty-eight classes of beings (Nijuuhachibushuu 二十八部衆) that serve as attendants to Senju Kannon 千手観音, and among the 33 manifestations of Kannon 観音 mentioned in the Lotus Sutra. They are also regarded as guardians of children, and it is in this role that one of their kings, called Sendan Kendatsuba-ou 栴檀乾闥婆王, figures at the centre of the Doujikyou mandara 童子経曼荼羅, which is used in Esoteric Buddhist rituals to ward off danger and illness from children. In Japan, the Kendatsuba are seldom represented.

Says Soothill in his Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms: “Spirits on Gandha-mādana 香 山, the fragrant or incense mountains, so called because the Gandharvas do not drink wine or eat meat, but feed on incense or fragrance and give off fragrant odours. As musicians of Indra, or in the retinue of Dhrtarastra  they are said to be the same as, or similar to, the Kinnaras. The Dhrtarastra are associated with soma, the moon, and with medicine. They cause ecstasy, are erotic, and the patrons of marriageable girls; the Apsaras are their wives, and both are patrons of dicers.” <end Soothill quote> There are many kinds of transcriptions of Gandharva. Soothill mentions the following: 乾闥婆, 乾沓婆, 乾沓和, 健達婆, 健闥婆, 健達縛, 健陀羅, 彦達縛. they are said to be the same as, or similar to, the Kinnaras. The Dhrtarastra are associated with soma, the moon, and with medicine. They cause ecstasy, are erotic, and the patrons of marriageable girls; the Apsaras are their wives, and both are patrons of dicers.” <end Soothill quote> There are many kinds of transcriptions of Gandharva. Soothill mentions the following: 乾闥婆, 乾沓婆, 乾沓和, 健達婆, 健闥婆, 健達縛, 健陀羅, 彦達縛. |

|

RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE

|

|

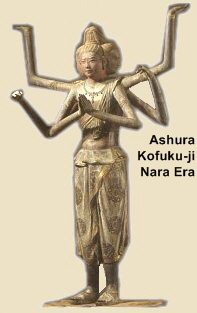

Ashura 阿修羅

Skt: Ashura, Asura

Image: Ashura

Nara Era, 8th century

(Kofuku-ji, Nara Pref.)

Ashura-Ou

Ashura-O

The King of the Ashura, who sometimes represents all the Ashura in artwork

Common Misspelling:

Asyura

Member of the

28 Legions (Nijūhachi Bushū)

|

Beings just below humans in the Six States of Existence. Asuras are demigods, or semi-blessed beings. They are powerful, yet fierce and quarrelsome, and like humans, they are partly good and partly evil. In their earliest Hindu and Brahman manifestations, the Ashura are always fighting the Ten (Deva) for supremancy (often battling the deities commanded by Taishakuten, the Lord Indra of Hindu mythology). The Ashura are sometimes compared to the Titans of Greek mythology -- in one legend, they stand in the ocean with the water coming up to only their knees. But in most accounts, the Ashura are not giants. Some say Ashura was an Indian royal who converted to Buddhism. In other Hindu traditions, Ashura is a sun goddess, feared for bringing droughts. Beings just below humans in the Six States of Existence. Asuras are demigods, or semi-blessed beings. They are powerful, yet fierce and quarrelsome, and like humans, they are partly good and partly evil. In their earliest Hindu and Brahman manifestations, the Ashura are always fighting the Ten (Deva) for supremancy (often battling the deities commanded by Taishakuten, the Lord Indra of Hindu mythology). The Ashura are sometimes compared to the Titans of Greek mythology -- in one legend, they stand in the ocean with the water coming up to only their knees. But in most accounts, the Ashura are not giants. Some say Ashura was an Indian royal who converted to Buddhism. In other Hindu traditions, Ashura is a sun goddess, feared for bringing droughts.

In early Vedic legends, which celebrate the victory of the Aryan invaders who entered India around 1500 BC and conquered the local Dravidian people, we find mention of the Asura King (Ashura O). The Aryans portrayed their own gods as benevolent heavenly beings, while the gods of the conquered people were demoted to serving as subjects of the Aryan deities. But the Asura King, one of the major gods of the conquered Dravidians, was a threat to the victors, and was subsequently demoted to demon status. According to Aryan lore, Asura was defeated by Taishakuten (Indra) and hid thereafter in a lotus flower growing in the Icy Lake (Skt. = Anavatapta). The word asura was then sometimes translated as “non-god” or “anti-god” to complete the Aryan victory and to deny any chance of ranking the Asura among the heavenly gods. But with the emergence of Buddhism, Ashura is sometimes identified with sunshine and helping crops to grow. Many sources depict the Asura as demons, yet they are not always portrayed as sinister, and some are even godlike in their piousness. Among the truly evil was Vritra. <Photo Above: Modern mask reproduction> In early Vedic legends, which celebrate the victory of the Aryan invaders who entered India around 1500 BC and conquered the local Dravidian people, we find mention of the Asura King (Ashura O). The Aryans portrayed their own gods as benevolent heavenly beings, while the gods of the conquered people were demoted to serving as subjects of the Aryan deities. But the Asura King, one of the major gods of the conquered Dravidians, was a threat to the victors, and was subsequently demoted to demon status. According to Aryan lore, Asura was defeated by Taishakuten (Indra) and hid thereafter in a lotus flower growing in the Icy Lake (Skt. = Anavatapta). The word asura was then sometimes translated as “non-god” or “anti-god” to complete the Aryan victory and to deny any chance of ranking the Asura among the heavenly gods. But with the emergence of Buddhism, Ashura is sometimes identified with sunshine and helping crops to grow. Many sources depict the Asura as demons, yet they are not always portrayed as sinister, and some are even godlike in their piousness. Among the truly evil was Vritra. <Photo Above: Modern mask reproduction>

In Japan, Ashura is often shown with three faces and six arms, with the side faces often expressing the violent warrior aspects associated with Ashura’s Hindu origin. With Ashura’s arrival to Japan in the 6th century from Korea and China, the deity is adopted as a guardian deity of Buddhism.

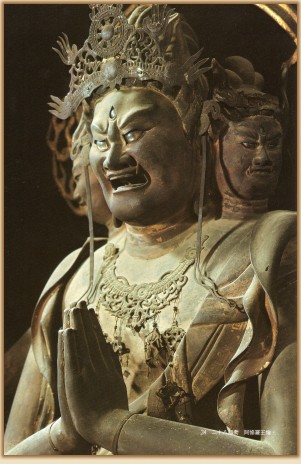

Asura (Ashura)

Sanjusangendo, 12th Century

Lifesize Wooden Statue

SAYS JAANUS (Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System): Sanskrit = Ashura. Also abbreviated to shura 修羅. Among the Indo-Iranians, the term asura, ahura in Avestan, originally referred to a divine being on a par with the gods, in which sense it is preserved in Ahura Mazda, the name of the supreme deity in Zoroastrianism. After the Aryans separated from the Iranians, the asura gradually declined in status, and the term acquired the opposite meaning of an antigod, demon, or enemy of the gods (Ten 天). The struggles between Indra, (Jp: Taishakuten 帝釈天) and the asura are an important theme in Indian mythology, and it is probable that they reflect the Aryans' struggles against the earlier inhabitants of India. This dual nature of the asura is also reflected in Buddhism, where on the one hand they are counted among the eight classes of beings who protect Buddhism (Hachibushuu, this page) while on the other hand their realm (said to be located on the ocean floor) is considered to be a world of strife and represents one of the six realms of transmigratory existence (rokudou-e 六道会). The Gekongoubu-in 外金剛部院 of the Taizoukai Mandara includes several asura, all two-armed and seated, but in Japan they usually are found in sets of the Hachibushuu, the eight kinds of guardian spirits of the Dharma (Buddhist law), when they are represented with three faces and six arms. The oldest statuary representation of Ashura is an 8c seated clay image at Houryuuji 法隆寺 in Nara. The most famous Ashura sculpture is a hollow dry-lacquer standing image of the 8c at Koufukuji 興福寺 in Nara.

ASHURA O:

Quote from Flammarion Iconographic Guide

The king of the Ashura, often shown with three-faced head (or three heads) and six arms (sometimes four arms). He is often shown holding the sun, moon, bow and arrows, a mirror, and has two hands in the Anjali mudra. Hair is usually bristling. The king of hunger, an ogre in perpetual anger, the king of quarrels. Of the three heads (faces), the central head has a suffering expression, and the others appear angry. <end quote>

FROM SITE READER:

In Pali, “Ashura” literally means "one who is not touched by light." In Pali, the term “Ashura O” can also be translated as "one who doesn't drink sura (alchohol)." In Indian mythology, Ashura O and his followers were the rulers of the Trayastrimsha Heaven, but they were thrown out of that heaven by Lord Indra because they were fond of drinking and were often drunk. After being thrown out, the Ashura vowed never to drink again. <Editor’s Note: I have not confirmed these Pali translations, and none of the books on Japanese Buddhism in my possession give this interpretation.>

|

|

RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE

|

|

Karura 迦楼羅

Skt: Garuda

See the Karura Page for more details and photos

Member of the

28 Legions (Nijūhachi Bushū)

|

Karura are bird-men (man’s head, bird’s body). These creatures sprang from the Brahmanic pantheon, and were mortal enemies of the naga (serpents and dragons). Karura are bird-men (man’s head, bird’s body). These creatures sprang from the Brahmanic pantheon, and were mortal enemies of the naga (serpents and dragons).

It is said that only dragons who possess a Buddhist talisman or dragons who believe in the Buddhist teachings can escape from the Karura.

In Japanese sculpture, the Karura are often represented as large ornate birds with human heads treading on serpents, but statues of the Karura are not very common in Japan -- the most well-known of these sculptures is at Kyoto’s  Sanjusangendo. Sanjusangendo.

Masks of the creature, however, including gyodo and noh masks, appear quite frequently, even in modern times.

In South East Asia the walls of temples are often decorated with Karura, as at Angkor or Java. In some sculptures of Fudō Myō-ō, there is a flame behind Fudō that some say was vomited by Karura.

|

|

RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE

|

|

Kinnara 緊那羅

Sanskrit: Kimnara

Photo courtesy of

this outside site

Member of the

28 Legions (Nijūhachi Bushū)

|

The Kinnara are heavenly musicians depicted in early times with human bodies and horses heads. They are also represented in the shape of a bird with human head holding a musical instrument and are reputed to have marvelous voices. The Kinnara are heavenly musicians depicted in early times with human bodies and horses heads. They are also represented in the shape of a bird with human head holding a musical instrument and are reputed to have marvelous voices.

The Kinnaras (Kimnara) are celestial musicians, officiating at the court of Kuvera (Kubera). In China, Buddhist monks claim that the Taoist deity Zao Jun, a Kitchen deity, is in fact a Kinnara. In India and its Hindu legends, the Kinnara are birds of paradise, and typically represented as birds with human heads playing musical instruments. This iconography is strikingly similar to that of the Karyoubinga -- heavenly musicians with the bodies of birds and the heads of humans.

At Sanjusangendo in Kyoto, two of the 28 followers of Kannon in the temple are Taishakuten (Indra), and his attendant, Kinnara, who is playing the drum (see photo above). The Kinnara also serve Tamonten (Bishamonten). Not commonly represented in the Buddhist artwork of Japan.

Kinnara is half-man,

half-bird in Indonesian.

Photo courtesy of

http://www.kinnara.or.id/

|

|

RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE

|

|

Magoraka 摩睺羅伽

Makora, Makura

Skt = Mahoraga

At Kofuku-ji in Nara, Magoraka is represented by the deity Hitsubakara畢婆迦羅

Member of the

28 Legions (Nijūhachi Bushū)

|

Of all the people-like non-humans, the Magoraka are the most vague. In some Chinese dictionaries they are defined as “serpents who walk on their breasts.” Of all the people-like non-humans, the Magoraka are the most vague. In some Chinese dictionaries they are defined as “serpents who walk on their breasts.”

In other representations, they are serpentine musicians. They belonged originally to the Brahmanic pantheon, and in Buddhism were partly assimilated by the dragon.

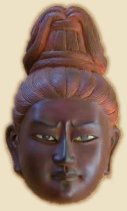

Photo at Right:

Heian Era, by sculptor Chōsei

Housed at Kōryūji Temple 広隆寺 in Kyoto

|

LEARN MORE

|

|