|

|

|

|

MAHAYANA SCHOOL

BEFORE BUDDHISM IN JAPAN

This is a side page. Return to Parent Page.

Overview | Hinduism | Theravada | Mahayana  | Vajrayana | Rifts | Vajrayana | Rifts

RELATED PAGES: Early Buddhism in Japan | Comparing Schools | Guide to Buddhism in Japan

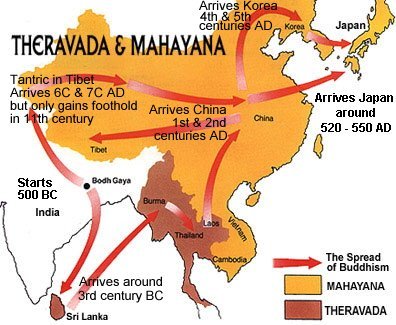

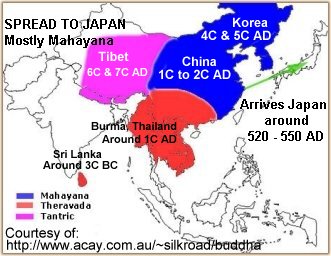

Map courtesy of Buddhanet

Mahayana School Mahayana School

Daijo Bukkyo in Japanese (Daijō Bukkyō). Also called the "Greater Vehicle," this school rose to prominence in India in the first century AD, splitting from the Theravada school. In contrast to Theravada Buddhism (with its emphasis on monastic life), the Mahayana school promises salvation to all who sincerely seek it -- monk and laity alike. The Mahayana tradition embodies the Bodhisattva Ideal -- the desire to liberate all beings from suffering -- whereas the Theravada tradition embodies the Arhat Ideal. See Comparing Saviors from the Theravada & Mahayana Traditions to learn more.

To bring salvation to the masses, the Mahayana school posits the existence of numerous Bodhisattva, the “compassionate ones,” who act as universal saviors of the common people. The worldly Bodhisattva (Bosatsu) is one who delays heavenly retirement (the rest of Nirvana) and remains on earth in various guises (reincarnations) to assist those seeking salvation and enlightenment. In contrast, the heavenly Buddha (Nyorai) are portrayed in Mahayana literature as concerned only remotely with worldly affairs. Buddha and Bodhisattva can appear or be reborn in any period. In some ages none appear. In others just one, perhaps two, and in others many. There is no rule. But the path to becoming a Bodhisattva or Buddha is open to all, including the laity.

Mahayana Buddhism is an umbrella concept for a great variety of sects, from the Tantric Sects found in Tibet and Nepal (secret Yoga teachings), to the Pure Land Sects found in China, Korea and Japan (reliance on simple faith in Amida Tathagata). The Mahayana school of India also gave birth to inward-looking Chan Buddhism (China), which then crossed the straights to Japan and flowered as Japanese Zen. For Chan (Zen) followers, the path to enlightenment is meditation.

Despite this proliferation in beliefs, Mahayana Buddhism still boils down to two general flavors -- the Madhyamika and the Yogacara (from Sanskrit). Madhyamika represents the middle view, the middle road, the path of relativity over extremes (e.g., extremes like existence vs. nonexistence, self vs. non-self). The Yogacara School emphasizes yoga -- the practice of meditation. In either flavor, the path to enlightenment is long and arduous, requiring followers to build up merit in this life to be reborn in the next life with better karma -- only after countless lives of karma-building and right-thinking does one attain enlightenment. Even so, the Mahayana doctrines still represent a quicker path to enlightenment than do the traditions of Theravada Buddhism. In particular, the “Pure Land” faith in Amida Nyorai is a Mahayana philosophy that represents a relatively “quick path” to enlightenment.

The Pure Land Sects claim that anyone who chants the name AMIDA will be granted entrance to the Pure Land (paradise) -- even those who fail to practice any Buddhist teachings during their life and only repent on their deathbed. Those who live in Amida’s Western Pure Land of Bliss, also called Jodo or Gokuraku -- a land devoid of worry or toil -- can focus their entire energies on attaining Buddhahood. Here, in the Pure Land, they need not worry about rebirth in the Six States of Existence -- for as inhabitants of the Pure Land, they are no longer trapped in the cycle of death and rebirth (Skt. samsara). The Nichiren Sect adamantly rejects the Amida “quick path” to salvation, claiming it actually harms the practice of Buddhism, for people need do nothing during their life and yet they can still gain salvation at the last moment by chanting Amida’s name. This does not, say Nichiren believers, lead to a life of reflection and improvement. Nichiren adherents claim that the Pure Land Sects are mistaken, that the chanting of Amdia’s name is only a first step, a preliminary practice, in religious advancement. This must be followed by rigorous practice and meditation. To Nichiren followers, chanting alone will not bring salvation.

The quick path to salvation for Amida followers (the Jodo and Jodo Shinshu Sects, the Pure Land Sects) is still longer than the “fast path, or liberation in one’s own lifetime” offered by Vajrayana Buddhism.

Buddhism did not arrive in Japan until the Asuka Period (approx. 538 - 710 AD), and the form that spread throughout the islands was Mahayana. Mahayana holds that not only priests (those having taken the Buddhist vows) but also the laity can attain enlightenment. In Japan, Mahayana Buddhism spread fast under the patronage of Imperial Prince Shotoku Taishi (574 - 622 AD; more correctly spelled Shōtoku), who is attributed with the construction of the famous Hōryū-ji (Horyu-ji) Temple in Nara, as well as many other temples throughout Japan. Click here for more details on Shotoku Taishi and various artwork of the prince. Buddhism did not arrive in Japan until the Asuka Period (approx. 538 - 710 AD), and the form that spread throughout the islands was Mahayana. Mahayana holds that not only priests (those having taken the Buddhist vows) but also the laity can attain enlightenment. In Japan, Mahayana Buddhism spread fast under the patronage of Imperial Prince Shotoku Taishi (574 - 622 AD; more correctly spelled Shōtoku), who is attributed with the construction of the famous Hōryū-ji (Horyu-ji) Temple in Nara, as well as many other temples throughout Japan. Click here for more details on Shotoku Taishi and various artwork of the prince.

Japan first learned of Buddhism from Korea, but the subsequent development of Japanese Buddhism and Buddhist sculpture was primarily influenced by China. According to tradition, Buddhism was introduced to Japan in 552 AD (other sources say 538 AD) when the king of Korean sent the Japanese Yamato 大和 court a small gilt bronze Buddha statue, some Buddhist scriptures, and a message praising Buddhism. Scholars continue to disagree on the exact date of the statue’s arrival. The Nihonshoki 日本書紀, one of Japan’s oldest extant documents, says the statue was presented sometime during the reign of Emperor Kinmei 欽明 (539 to 571 AD).

The Chinese and Korean missionaries who introduced Buddhism to Japan brought with them rituals and texts from both the Theravadin and Mahayana schools -- texts that had been very successful in China. They also brought their art (paintings, sculptures, etc.) and their techniques for carving and reproducing Buddhist texts and icons. Three texts were of particular influence in Japan, the Lotus Sutra, the Sutra of Golden Light and the Benevolent Kings Sutra. These were sometimes called the “Three Scriptures Protecting the State.” Indeed, the Japanese court’s early support for Buddhism was based in part on the court’s desire to use Buddhism as an instrument of power and imperial consolidation rather than an instrument of salvation for the common people. See Early Japanese Buddhism for more on this topic. Further, Confucian ideas from Han China had been current in the Japanese court since the 5th century AD. By the time Buddhism took root in Japan, the Japanese had become tolerant of three systems -- Shinto, Confucianism, and lastly Buddhism.

Another important feature of early Japanese Buddhism was the incorporation of numerous Hindu deities into Japan’s Buddhist pantheon. Writes scholar Richard Thornhill (PhD, lives in Tokyo) in Ancient Buddhist Monks Introduced the Hindu Pantheon: "The substantial sums of Hinduism that Buddhism carried along on its historic spread across Asia is not always appreciated. Indian Mahayanist philosophers, such as Nagarjuna, directed Buddhism back towards Hinduism, away from the rigid atheism of Theravada Buddhism. It was Mahayana Buddhism that spread to China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam. As a result, some of the earlier schools in Japan, such as Shingon, Kegon and Tendai, had largely Hindu pantheons (known as the Tenbu in Japan). In addition, the Mahayana scriptures are in Sanskrit, unlike the earlier Theravadin canon, which is in Pali, and numerous Sanskrit inscriptions can therefore be seen in Japanese temples, and sometimes on rocks in the mountains. Japanese folk religion is a rich mélange, but a number of Hindu Gods play an important role. For example, of the Seven Gods of Good Fortune whose temples people visit at New Year, three are Hindu: Daikoku (Mahakali), Bishamon (Vaishravana) and Benten, Benzaiten or, most formally, Bensaiten-sama (Sarasvati). A popular temple at Futako Tamagawa, Tokyo, displays Ganesha (elephant-headed Hindu deity) far more prominently than the Buddha." <end quote Richard Thornhill, last accessed on Aug. 29, 2010>

For followers in Japan, the defining value of their faith and practice is “compassion (Sanskrit karuna)” -- indeed, the Bosatsu of Compassion are among the most widely known Buddhist deities throughout the Asian region. The term Bosatsu (Bodhisattva) refers to those who have reached the final stage of transmigration and awakening, just prior to Buddhahood. In Mahayana Buddhism, those who become Bosatsu will certainly achieve Buddhahood, but for a time, they renounce the blissful state of Nirvana (freedom from suffering), vowing to remain on earth in various guises (reincarnations) to help all living beings achieve salvation. In Mahayana, then, the Bosatsu have renounced the ultimate state (Nirvana) out of “pure compassion” toward all beings.

Three Main Schools of Buddhism Today. Buddhism as practiced today is still divided into three main schools -- (1) Theravada, meaning School of the Elders, but pejoratively known as Hinayana or Lesser Vehicle; (2) Mahayana, meaning Greater Vehicle; and (3) Vajrayana, meaning Diamond Vehicle; also known as Tantric or Esoteric Buddhism. “Yana” is the Sanskrit term for vehicle. The bewildering number of sects are categorized into one of the three schools.

- Theravada (Hinayana)

Found mainly in Sri Lanka, Burma, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand. Often known as the Southern Traditions of Buddhism.

- Mahayana

Found mainly in China, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. Often known as the Northern Traditions of Buddhism.

- Vajrayana (Esoteric or Tantric Buddhism)

Practiced mainly in Tibet, Nepal, and Mongolia, but in Japan has a strong hold with the Shingon 真言, Tendai 天台, and Shugendō 修験道 sects. In Japan, Esoteric Buddhism is known as Mikkyō (Mikkyo) 密教). Along with Mahayana Buddhism, the Vajrayana traditions are often referred to as the Northern Traditions of Buddhism.

|

|