|

|

|

|

ARAKAN 阿羅漢 | RAKAN 羅漢 (Japanese)

ARHAT | ARHAN | ARAHAT | ARIHAT | ARIHAN (Sanskrit)

ari = enemy | han = kill or slay

Also Ōgu (J) 應供, “Worthy of Obeisance and Respect”

Ōgu is also one of the Ten Epithets 十號 (Jūgō) of the Buddha

Also Setsuzoku (J) 殺賊, “Foe Destroyer,” or “Enemy Slayer”

Also Mugaku (J) 無学, "Nothing Else to Learn"

Origin = India

Artwork, however, came to prominence in China

First Followers / Perfected Saints / Disciples of Historical Buddha

Arhatship = Ultimate goal of those practicing Theravada Buddhism

Arhat is juxtaposed to Mahayana concept of Bosatsu (Bodhisattva)

The highest goal of those practicing Theravada Buddhism. Those who attain Arhatship have “slain” their greed, anger and delusions, and “destroyed” their karmic residue from previous lives. They have learned the teachings of Shaka (Historical Buddha), earned the title of Mugaku ("nothing else to learn") and achieved the highest state attainable by Shaka’s disciples. Thus, they are no longer reborn into the world of suffering, no longer trapped in the cycle of samsara (the cycle of rebirth and redeath, the six states of existence). To followers of Mahayana Buddhism, however, the Therevadan Arhat ranks below the Mahayanan Bodhisattva on the chain of enlightenment. The highest goal of those practicing Theravada Buddhism. Those who attain Arhatship have “slain” their greed, anger and delusions, and “destroyed” their karmic residue from previous lives. They have learned the teachings of Shaka (Historical Buddha), earned the title of Mugaku ("nothing else to learn") and achieved the highest state attainable by Shaka’s disciples. Thus, they are no longer reborn into the world of suffering, no longer trapped in the cycle of samsara (the cycle of rebirth and redeath, the six states of existence). To followers of Mahayana Buddhism, however, the Therevadan Arhat ranks below the Mahayanan Bodhisattva on the chain of enlightenment.

|

The majority of Buddhist sculpture and art in Japan belongs to the Mahayana tradition. Although sculpture and art belonging to the Theravada and Vajrayana (Esoteric, Tantric) traditions is less prominent, it is nonetheless plentiful. Sects from all three schools are still active in Japan today. For more on these three main schools of Buddhism, click here. The below page discusses the origins of the RAKAN tradition, which is intimately associated with the Theravada School of Buddhism. With only a few exceptions, statues and artwork of the Arhat in Japan are not typically worshipped as the central objects of devotion. The majority of Buddhist sculpture and art in Japan belongs to the Mahayana tradition. Although sculpture and art belonging to the Theravada and Vajrayana (Esoteric, Tantric) traditions is less prominent, it is nonetheless plentiful. Sects from all three schools are still active in Japan today. For more on these three main schools of Buddhism, click here. The below page discusses the origins of the RAKAN tradition, which is intimately associated with the Theravada School of Buddhism. With only a few exceptions, statues and artwork of the Arhat in Japan are not typically worshipped as the central objects of devotion.

|

THE EARLY YEARS

|

THE FIRST DISCIPLES

The Theravadins clearly differentiate between monks and laity. Only those who practice the meditative monastic life (i.e. the monks) can attain spiritual perfection. Enlightenment is not thought possible for those living the secular life. Theravadins revere the Historical Buddha, but they do not pay homage to the numerous Buddha and Bodhisattva worshiped by Mahayana followers. The highest goal of a Theravadin is to become an Arhat (Sanskrit), or perfected saint. Other Arhat terms are:

- Pali: Arahant

- Chinese: Luohan | Lohan

- Japan: Arakan | Rakan

- Tibet: Gnas-brtam ??

- Tibet: Dgra Bcom Pa ??

|

|

The early Buddhists split into a number of factions following the death of the Historical Buddha (he died around 483 BC), each faction holding firm to its own interpretations. Roughly 500 years later, two main schools emerged -- the Theravada and Mahayana schools. Theravada sought to preserve the original and orthodox teachings of Gautama Buddha (the Historical Buddha). The Mahayana tradition was more flexible and innovative. At the time, the distinction between Theravada and Mahayana was politicized into arguments over “benefitting self” and “benefitting others.” Mahayana adherents insisted that only by benefitting others could one hope to benefit oneself. To Mahayana followers, the Theravada philosophy is false, for Theravada stresses “self benefit” -- practicing the monastic life for oneself, by oneself, strictly for one’s own emancipation. Indeed, the term “Hinayana,” meaning Lesser Vehicle, was attached to the Theravada school by Mahayana adherents, who hoped to portray the Theravada teachings as inferior. Thus, the term Hinayana is derogatory and used to denigrate Theravada traditions. It is a term that should be (and is) avoided by most modern scholars. Main Schools for more on this early schism. The early Buddhists split into a number of factions following the death of the Historical Buddha (he died around 483 BC), each faction holding firm to its own interpretations. Roughly 500 years later, two main schools emerged -- the Theravada and Mahayana schools. Theravada sought to preserve the original and orthodox teachings of Gautama Buddha (the Historical Buddha). The Mahayana tradition was more flexible and innovative. At the time, the distinction between Theravada and Mahayana was politicized into arguments over “benefitting self” and “benefitting others.” Mahayana adherents insisted that only by benefitting others could one hope to benefit oneself. To Mahayana followers, the Theravada philosophy is false, for Theravada stresses “self benefit” -- practicing the monastic life for oneself, by oneself, strictly for one’s own emancipation. Indeed, the term “Hinayana,” meaning Lesser Vehicle, was attached to the Theravada school by Mahayana adherents, who hoped to portray the Theravada teachings as inferior. Thus, the term Hinayana is derogatory and used to denigrate Theravada traditions. It is a term that should be (and is) avoided by most modern scholars. Main Schools for more on this early schism.

Teacher and Disciples Teacher and Disciples

Legend contends that the Lord Buddha (or Sakyamuni in Sanskrit; he is no longer called Siddhartha after reaching Buddhahood) decided to keep his achievement and teachings to himself, for others would not believe or comprehend. But his mind was changed by the appearance before him of Brahman (the chief Hindu god of that age; Jp. = Bonten), who urged him to preach what he had learned and help others along the same path. From that point on, until his death at age 80, the Buddha preached without interval. The Chinese transliterated Sakyamuni as Shakamuni, but this was later shortened to Shaka in both China and Japan. “Shaka” is another word for the Historical Buddha, for as a human, he was born into the Sakya (Shaka) clan, a tribe that ruled a small state that today is located in Tarai (Nepal) near the border with India.

His companion ascetics were the first to become his disciples, and soon afterwards they too attained enlightenment -- in Sanskrit they are known as the Arhan (Jp. = Arakan 阿羅漢), an Indian word meaning "one who is worthy of receiving obeisance" or “slayer of enemies.” Arhatship is the main goal of all who practice Theravada Buddhism.

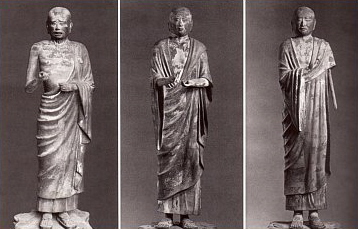

The most famous of the early disciples are called the Ten Great Disciples (Jūdai Deshi 十大弟子), and they played a major role in Buddhism’s early development and transmission within India.

The Ten Great Disciples (Jūdai Deshi 十大弟子)

Above: 734 AD, Kofukuji Temple, Japan

(L) Ragora (M) Subodai (R) Furuna

Below: 734 AD, Kofukuji Temple, Japan

(L) Kasen-en (M) Mokukenren (R) Sharihotsu

FOUR ARHATS. In the earliest Indian sutras, however, the Historical Buddha is said to have asked only four arhats to remain in the world to propagate Buddhist law (dharma). Each of the four was associated with one of the four compass directions.

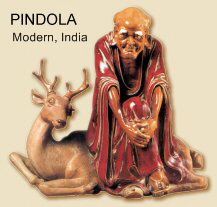

Bindora Baradaja (J) 賓度羅跋羅惰闍. Also called Binzuru (J). Pindola Bharadraja (Skt). Associated with compass direction = West; resides with 1,000 disciples in Saikudani-shi (Skt. Aparagodani); the most widely revered of the Arhats in Japan; all the others are less known to Japanese lay worshippers, and they rarely serve as the central objects of devotion. Pindola, however, according to the Flammarion Iconographic Guide on Buddhism, is the Arhat par excellence in Japan, and is mainly worshipped by lay people. Quote: “In Japan, Pindola is represented as an old man seated on a high-backed chair, with white hair and bushy eyebrows. Statues of him, in painted wood or stone, are usually well worn, since the faithful follow the custom of rubbing a part of the effigy corresponding to the sick parts of their bodies, as he is reputed to have the gift of healing. [Schumacher here. Statues that are rubbed in Japan are called nadebotoke 撫で仏 , literally "rubbing Buddha statues;" natabotoke are not limited to Binzura, but include other deities like Jizō, Kannon, Daikokuten, and Fudō.] He is also very frequently offered red and white bibs and children’s caps to watch over the health of babies, so that his statue is often decked in rags. He is represented in painting as an old man seated on a rock, holding in his hand a sort of sceptre (Japanese shaku), or a sutra box and a feather fan. All the other Arahants are usually worshipped in Japan in his person. In some cases, his efficgy is placed in monastery refectories, as at the Jikido (Shakudo) in Todai-ji Temple (Nara), and in Hieizan.” <end quote> In Japan, a special Binzuru ceremony known as Binzuru Mawashi 賓頭盧廻 is held on the sixth of January at Zenkō-ji 善光寺 in Nagano. For details, see Gabi Greve’s Ceremony for Binzuru. Bindora Baradaja (J) 賓度羅跋羅惰闍. Also called Binzuru (J). Pindola Bharadraja (Skt). Associated with compass direction = West; resides with 1,000 disciples in Saikudani-shi (Skt. Aparagodani); the most widely revered of the Arhats in Japan; all the others are less known to Japanese lay worshippers, and they rarely serve as the central objects of devotion. Pindola, however, according to the Flammarion Iconographic Guide on Buddhism, is the Arhat par excellence in Japan, and is mainly worshipped by lay people. Quote: “In Japan, Pindola is represented as an old man seated on a high-backed chair, with white hair and bushy eyebrows. Statues of him, in painted wood or stone, are usually well worn, since the faithful follow the custom of rubbing a part of the effigy corresponding to the sick parts of their bodies, as he is reputed to have the gift of healing. [Schumacher here. Statues that are rubbed in Japan are called nadebotoke 撫で仏 , literally "rubbing Buddha statues;" natabotoke are not limited to Binzura, but include other deities like Jizō, Kannon, Daikokuten, and Fudō.] He is also very frequently offered red and white bibs and children’s caps to watch over the health of babies, so that his statue is often decked in rags. He is represented in painting as an old man seated on a rock, holding in his hand a sort of sceptre (Japanese shaku), or a sutra box and a feather fan. All the other Arahants are usually worshipped in Japan in his person. In some cases, his efficgy is placed in monastery refectories, as at the Jikido (Shakudo) in Todai-ji Temple (Nara), and in Hieizan.” <end quote> In Japan, a special Binzuru ceremony known as Binzuru Mawashi 賓頭盧廻 is held on the sixth of January at Zenkō-ji 善光寺 in Nagano. For details, see Gabi Greve’s Ceremony for Binzuru.

|

Binzuru (Pindola Bharadvaja), Wood, Edo Era, 18th Century. At Todaiji Temple in Nara. Pindola was one of the sixteen arahats, who were disciples of Shaka Nyorai. Pindola is said to have excelled in the mastery of occult powers. It is commonoly believed in Japan that when a person rubs a part of the image of Binzuru, and then rubs the corresponding part of his/her body, the ailment there will disappear. <Text from Todaiji Temple>

|

|

- Kanakabassa (J) 迦諾迦伐蹉; Kanakavatsa (Skt.)

North; resides with 500 disciples in Kashmir (Hokukuru-shu; J)

- Hantaka (J) 半託迦; Panthaka (Skt.)

East; resides with 1,300 disciples in the Heaven of 33 Gods, or Toshoshin-shu (J).

- Nakora (J) 諾距羅; Nakula (Skt.)

South; resides with 800 disciples in Nansenbu-shu (J)

Above listings also from M.V. de Visser, “The Arhats in China and Japan,” Published 1919, page 62.

Binzuru (Pindola Bharadvaja) at Todaiji Temple in Nara

Photo at left by Carl & Ann Purcell

Same seated statue as shown above.

Wood, Edo Era, 18th Century

16 ARHATS, 18 ARHATS, 500 ARHATS

<Abridged from Flammarion Iconographic Guide>

In later centuries, the number increases from four to 16, then later on to 18. The grouping of 16, together with their names, was not widely known until around 654 AD, but thereafter rises to prominence in China with the Chinese translation of the Fa Zhuji Sutra (法住記) from India. For much more on the 16, plus their Japanese and Sanskrit names, please click here. Tradition also asserts that 500 disciples were present when Shaka Nyorai (the Historical Buddha) expounded the Flower Sutra on Vultures Peak (Rajagrha). Not all agree on the origins of this grouping of 500 Arhats, although in Japanese artwork they appear rather frequently in the 12th and 13th century, especially the 100 kakemono paintings reportedly brought to Japan from China by the Japanese monk Eisai in the 12th century (now located at Daitoku-ji Temple in Kyoto). Many point to the Mahaparinirvana Sutru and Saddharmapundarika Sutra as the origin, for these texts refer to 500 beggars who were formerly rich merchants, but after meeting the Historical Buddha, they learned and accepted his teachings. Most were not originally given names, but documents at the Kenmyou-in Temple dating from the Nanboku Period (1127 to 1279 AD) contain a list of names for all 500. For details on the 500 Arhats, click here. <end abridged text>

Death of the Teacher

By tradition, the date of the Historical Buddha’s death is February 15. In Japan, a Buddhist service called Nehan'e is performed each year on this day. According to legend, the Buddha's death was attended by gods, celestial maidens, arhats, people, and animals -- even the plants gave homage. The story of the Buddha's last moments are recorded in great detail in the sutra known as The Sutra of the Great Extinction (Pali language), in which the Buddha declares that he has taught all, withholding nothing, for he has no intention to exercise control by means of secret doctrines. Near his death he said: "Make the self your light, make the law your light."

Death of Buddha, Painting dated to 1086 AD, Byōdōin Temple 平等院

Arhats in attendance at death of Historical Buddha.

Click here from many more wonderful photos.

|

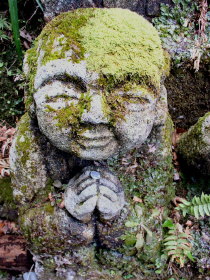

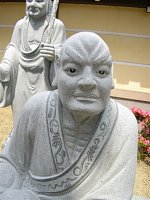

Arakan | Rakan In Japan

at Otagi Nenbutsuji Temple, Arashiyama, Kyoto

Below Photos by Ed Jacob

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Who Made the Statues at

Otagi Nenbutsuji Temple, Arashiyama, Kyoto

(see above photos)

Nishimura Kōchō (1915-1989) 西村公朝 was a famous modern carver of Buddha statues and restored many old statues at various temples. He wrote many books about Buddhist statuary and appeared often on Japanese national TV programs to talk on the subject of appreciating Buddhist statues. Born on June 4 (1915) in Osaka, he later studied art at the Tokyo University of Arts. For a time, during WW2, he was in China. Once he returned to Japan, he began his lifework of restoring the many statues of Kannon and other deities located at the famous Kyoto temple named Sanjusan Gendo 三十三間堂. When he was 37, he became a fully ordained priest of the Tendai sect but continued to pursue his restoration work and his own carvings. In 1955 he was appointed head priest at Otagi Nenbutsu Ji Temple 愛宕念仏寺 in Kyoto, a rather worn-down place when he took over. During his tenure at the temple, he invite lay people and showed them how to carve simple stone statues. These statues (the so-called "1200 Arhats") now adorn the temple grounds. A temple visit is highly recommended for anyone visiting Kyoto. Nishimura taught at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and the Hieizan University of the Tendai Sect. In 1986, he received the honorable title Tendai Daibusshi Hōin 天台大仏師法印 (lit. Great Sculptor of Buddha Statues), the highest rank given to statuary artists but one not bestowed for many years prior to Nishimura. He died on December 2, 2003, at the age of 89 years. <Above text by Gabi Greve. See her page on Daibusshi Nishimura>

Otagi Nenbutsu-ji Temple in Arashiyama, Kyoto

Below text (& above photos) courtesy Ed Jacob

See Ed’s original page at: Otagi Nenbutsuji Temple

Arashiyama is one of Kyoto’s most beautiful neighbourhoods, and hundreds of thousands of tourists visit there every year, but unfortunately, almost no one ever makes it to the area’s most interesting temple. It’s called Otagi Nenbutsu-ji, and it has some of the funniest, most fascinating and beautiful Buddhist sculptures in the entire country.

Originally founded by Emperor Shotoku in the middle of the eighth century, this temple has had some seriously bad luck. It was first built in the Higashidera area of Kyoto, but was destroyed by a flood of the Kamo River, and was rebuilt as a branch of Enryaku-ji, the famous Tendai sect temple on Mt. Hiei. Its main hall was burned to the during a civil war in the thirteenth century, and after moving to its present location in 1922, it suffered severe damage in a typhoon.

From the road, Otagi Nenbustu-ji looks like a very ordinary temple, but after passing through the gate, with its two typically terrifying Nio statues (the fierce looking guardians one often finds at the entrance to temples), you will notice two more Nio, and these definitely tend toward the cute, rather than the ferocious end of the spectrum.

These kawaii guardians are just the beginning though, and there are more than 1200 statues on the temple’s grounds. Walking up the path to the main hall, there are dozen or so strange little faces peering down at you, most of them half-hidden in the tall grass. Although they will give you some hint of the strangeness you are about to encounter, most visitors are still shocked when they see the hundreds of bizarre figures carved in grey stone by the main hall of the temple.

These statues are called rakan, and they represent the 500 disciples of Buddha. Although many Buddhist sculptures are carved to represent exquisite beauty or terrifying ferociousness, rakan almost always seem to be carved in the spirit of humour and good fun. There are also Rakan-ji temples in Otaru (Hokkaido) and Oita (Kyushu) with carvings every bit as bizarre as those at Otagi Nenbutsu-ji, but the statues here are special because most of them were made by amateur carvers.

In 1981, when the 1950 typhoon damage was finally repaired, worshippers at the temple decided to donate rakan sculptures to the temple in honour of its refurbishing. A famous sculptor, Kocho Nishimura taught hundreds of sculptors, amateur and professional alike how to carve statues from stone, and the result is a delightful mix of serene and scary, somber and silly.

Spend a few hours there and see if you can find the surfing Buddha, the two tipplers, the saxophone player, the photographer and the disciple doing a handstand. Since the installation of the Rakan, a custom has evolved among visitors to the temple of trying to find a statue that resembles your own face. It can be fun, but you may be in for a shock if you go with someone else and are suddenly told that the buck-toothed, bowl cut-sporting statue with a nose the size of a potato looks a lot like you.

The temple must be one of the mossiest, most eroded places in Kansai, and walking its grounds, one has the distinct impression that man is fighting a losing battle with nature here. All in all it’s a very mysterious place, always a little dark and always the moss on the statues and the way they are being eroded just adds to the atmosphere.

Getting There:

From Kyoto station, take bus 72 to Otagidera Mae  . From Hankyu Arashiyama station, take bus 62 or 72 to Otagidera Mae. If you know Arashiyama, go to Kitano Nenbutsu-ji and follow the walking path north. You'll come to Otagi in about 10 minutes. . From Hankyu Arashiyama station, take bus 62 or 72 to Otagidera Mae. If you know Arashiyama, go to Kitano Nenbutsu-ji and follow the walking path north. You'll come to Otagi in about 10 minutes.

<end text by Ed Jacob; Visit Ed Jacob’s Site>

Thank you for your story and your wonderful photos.

|

|

|

BELOW TEXT COURTESY OF JAANUS

Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System

Excellent Dictionary of Buddhist Concepts.

Used Here with Permission of JAANUS.

16 ARHATS, Jūroku Rakan, 十六羅漢

www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/j/juurokurakan.htm

|

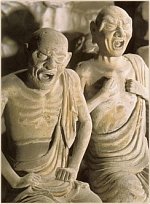

Ascetics Near Starvation

Horyuji Temple, 711 AD

North Side, Tohonshimengu

|

|

Jūroku Rakan literally means “Sixteen Arhats.” The saintly ascetics who gathered at the death and nirvana (nehan 涅槃) of the Buddha Sakyamuni (Shaka 釈迦) and were ordered by him to remain in this world as witnesses to the truth of the Law or Buddhist teachings. Typical depictions in painting or sculpture show them with aged faces, emaciated bodies and the frugal clothing of Indian ascetics or wise men.

As listed in the FAZHUJI 法住記 (Jp: HOUJUUKI) translated into Chinese by Xuanzang 玄奘 (Jp: Genjou 602-64), the sixteen are:

- Bindorabaradaja 賓度羅跋羅惰闍 (Sk: Pindolabharadraja)

- Kanakabassa 迦諾迦伐蹉 (Sk:Kanakavatsa)

- Kanakabaridaja 迦諾迦跋釐堕闍 (Sk: Kanakabharadraja)

- Subinda 蘇頻陀 (Sk: Subinda)

- Nakora 諾距羅 (Sk:Nakula)

- Badara 跋陀羅 (Sk: Bhadra)

- Karika 迦哩迦 (Sk:Kalika)

- Bajaraputara 伐闍羅弗多羅 (Sk: Vajrap utra)

- Jubaka 戌博迦 (Sk:Jivaka)

- Hantaka 半託迦 (Sk:Panthaka)

- Ragora 羅怙羅 (Sk:Rahula)

- Nagasena 那伽犀那 (Sk:Nagasena)

- Ingada 因掲陀 (Sk:Angaja)

- Banabasu 伐那波斯 (Sk:Vanavasin)

- Ajita 阿氏多 (Sk:Ajita)

- Chudahantaka 注荼半託迦 (Sk:Chudapanthaka)

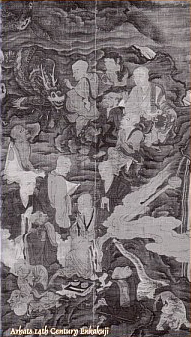

A largely different group of sixteen rakan is mentioned in the sutra, AMIDAKYOU 阿弥陀経, with only Bindorabaradaja and Chudahantaka being the same. Traditions also exist of groups of Eighteen (juuhachi rakan 十八羅漢) and Five Hundred arhats (Gohyaku rakan 五百羅漢; see below entry). Paintings of the Sixteen arhats are known to date from the Tang dynasty and were produced frequently in China through the Song period (12c), typically as wall paintings or sets of hanging scrolls. In general, Chinese rakan painting can be divided into two stylistic types which influenced the development of two painting traditions in Japan. The orthodox style, featuring careful attention to detail, rich color, and gold, is associated with the Northern Song painter Li Longmin 李竜眠 (Jp: Ri Ryuumin, also known as Ch: Li Gonglin, Jp: Ri Kourin 李公麟, 1049?-1106). These works are known as riryuuminyou rakan 李竜眠様羅漢. In contrast, the Five Dynasties priest Guanxiu 貫休 (Jp: Kankyuu 832-912) created a distinctive ink monochrome style of rendering the Sixteen arhats, known as zengetsuyou rakan 禅月様羅漢. In Japan the subject is said to have been introduced from China in 982 by the priest Chounen 奝然 (?-1016). Several sets of Chinese paintings extant in Japanese collections testify to the early popularity of the subject in Japanese temples. Japanese versions, like their Chinese prototypes, typically were done as a set of sixteen hanging scrolls or with the rakan grouped in one or two hanging scrolls. In both countries, because of the relative humanity of the subjects and their "foreign-ness" paintings of the Sixteen rakan became "exercises in grotesquerie or realism," the very frequency of commissions offering artists chances to explore distortion of form or to display their virtuosic control of the brush. The theme was particularly popular at Zen 禅 temples, where polychrome wood sculptures of the Sixteen rakan were often placed in the second floor chamber of the gates (*sanmon 三門) of Zen temples (for example Toufukuji 東福寺, and Nanzenji 南禅寺, Myoushinji 妙心寺). In the Edo period the juuroku rakan images continued to be produced, but by artists not associated with temples, and the paintings were used in secular contexts. The juuroku rakan were even parodied by ukiyo-e 浮世絵 artists. Edo-period gardens sometimes feature 16 stones arranged in reference to the juuroku rakan.

Rakan 羅漢 (Courtesy JAANUS)

www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/r/rakan.htm

Chinese = Lohan, Sanskrit = Arhat. The Japanese term “Rakan” is an abbreviation of the Japanese term “Arakan (阿羅漢),” itself a translation of the Sanskrit term “Arhan.” Also called “Ougu (應供).” The highest diciples of Shaka 釈迦. In Theravada Buddhism, rakan are revered as having completed their training and ranked as mugaku 無学, "nothing else to learn," which indicates that they achieved the highest point that a disciple of Shaka could reach. However, in Mahayana Buddhism, rakan who aim at their own salvation are ranked below the Boddhisattva (Bosatsu 菩薩). It is said that when Shaka entered nirvana (涅槃), rakan were ordered to live in this world and protect the True Law (shouhou 正法). Therefore, rakan are depicted in the guise of priests, with buddhist monks' robes (kesa 袈裟) and bald heads (teihatsu 剃髪). Rakan were depicted in painting in the Six Dynasties (c222-589), but after Xuanzhuang 玄奘 (Jp: Genjou: 600-664) translated HOUJUUKI 法住記 containing the biographies of the sixteen rakan (see above entry), the cult of rakan became popular . Since the 9c numerous paintings and sculptures of rakan were produced in both China and Japan. Typically, they are depicted in a group of 16 or 18 (juuhachi rakan 十八羅漢), and this may be expanded to 500 (gohyaku rakan 五百羅漢; see below entry). Rakan paintings are often stylistically classified into two groups: the Riryuumin-you 李龍眠様, the moderate style with thin, even lines which is associated with the 11c painter Li Gonglin 李公麟 (also called Li Longmean [Jp: Ri Ryuumin]), and the Zengetsu-you 禅月様, a bolder style with exaggerated lines that is associated with the 9c painter Guanxiu 貫休 (also called Chanyue [Jp: Zengetsu]). However, there are quite a few examples which are not included in either of these two styles.

16 Arhats, Heian Era, 11th Century

Formerly owned by Shojuraigoji Temple, Shiga

Photo courtesy Tokyo National Museum

95.9-97.2x57.8-52.2., National Treasure

Click here (outside link) for more arhat images

500 RAKAN (Courtesy JAANUS)

Gohyaku Rakan 五百羅漢

www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/g/gohyakurakan.htm

Chinese = Wubai Luohan. Five hundred arhats (rakan 羅漢), a Buddhist art subject developed in China featuring large numbers of Indian wise men usually accompanied by servants. There is no agreement among scholars as to the origin of this grouping, (see below note), although several Chinese texts mention rakan as protective saints, who guard the Buddhist law until the coming of Miroku (弥勒, Skt: Maitreya), the Buddha of the Future. The Chinese belief that the Five Hundred Luohan inhabited a peak beyond the Stone Bridge (Shakkyou 石橋) on Mt. Tiantai (Jp: Tendaisan 天台山) is probably an adaptation into popular Buddhism of Taoist legends about the locale as the home of immortals. Tang-period Chinese were also familiar with Indian legends of five hundred arhats believed to live on Mt. Buddhavanagiri near Rajagrha. It is not clear whether the number "500" refers to 500 specific individuals or simply indicates a large number. Beginning in the 5c large groups of rakan were depicted as seated, a pose that was also used for portrayal of independant rakan images. By the 10c and 11c, rakan depictions were elaborated with landscape or domestic interior settings as the rakan cult became wide spread. The best-known painting of five hundred rakan is the set of 100 hanging scrolls (divided among Daitokuji 大徳寺, Kyoto, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and other collections) by Lin Tinggui 林庭珪 (Jp: Rin Teikei, act.1174-89) and Zhou Jichang 周季常 (Jp: Shuu Kijou late 12c).

The inscription of 1178 also states that the set was originally commissioned by a merchant family as a gift to a temple, and this type of popular patronage probably lies behind many of rakan paintings. The complete set of scrolls by Lin and Zhou was in Japan by the late 14c as copies were made by the Japanese painter-priest Minchou 明兆 (1351-1431) for Toufukuji 東福寺 in 1386 and for Engakuji 円覚寺, Kamakura. Although all 500 of the rakan were occasionally painted on a single scroll, more frequently depictions were done on a series of scrolls or large wall surfaces. The subject was revived in Ming China (14-17c) and similarly found renewed interest in Edo period Japan. Ike Taiga's 池大雅 (1723-76) screen, *fusuma 襖 painting of five hundred rakan at Mampukuji 万福寺 is a well-known but unorthodox example. More typical are the 100 scrolls by Kanou Kazunobu 狩野一信(1815-63) at Zoujouji 増上寺, Tokyo. Rock sculptures of the five hundred rakan were created at temples all over Japan, including Kitain 喜多院 in Saitama Preference, Rakanji 羅漢寺 in Ooita Preference, and Sekihouji 石峰寺 in Kyoto.

<end text from JAANUS>

NOTE ON ORIGINS OF 500 ARHATS

Many point to the Mahaparinirvana Sutru and Saddharmapundarika Sutra as the origin, for these texts refer to 500 beggars who were formerly rich merchants, but after meeting the Historical Buddha, they learned and accepted his teachings.

|

|

500 Rakan in Chiba

The Big Buddha at Nihon-ji Temple in Chiba Prefecture is a representation of Yakushi Nyorai (the Medicine Buddha). Carved out of stone, and standing 31.05 meters in height, this Daibutsu, plus 1,500 smaller statues, were carved by master artisan Jingoro Eirei Ono and his 27 apprentices in the 1780s and 1790s. Click here for more on Japan’s Big Buddha statues. At the same location, one can find carvings of 500 Arhats (Gohyaku Rakan), and a gigantic stone carving of the Kannon (Hyaku Shaku Kannon). The Rakan images (538 bodies standing close to each other on a slanting surface) took 20 years to carve. The project, attributed to the 15th chief priest of Nihon-ji, also occurred during the latter half of the Edo Period.

500 Rakan at Houjyu-in 宝樹院 500 Rakan at Houjyu-in 宝樹院

Chiba Prefecutre, Sakura City 佐倉市上座

500 stone statues of the Rakan were created in 2003 (Heisei 15) in honor of the temple's 650th anniversary. To see dozens of photos of these statues, please visit the below Japanese language site:

asanori.web.infoseek.co.jp/

HP_S7/IMG_S159/SYA_159.htm

538 RAKAN

Kunisaki Peninsula, Oita Pref. Kunisaki Peninsula, Oita Pref.

www.pict.com/tomi/budhism/page4.html

Located at Toko-ji temple, Kunisaki, Oita Prefecture, Japan. Home to 538 stone-carved Rakans, reportedly carved during the late Heian or early Kamakura periods. Just one of many sites on the Kunisaki Peninsula in southern Japan (Kyushu), which is home to many stone carvings of the Buddha and Bosatsu and also home to numerous Sacred Sites and Holy Mountains. See Pilgrimage Guide for more details on Japan’s holy places.

ZENTSUJI TEMPLE (善通寺) ZENTSUJI TEMPLE (善通寺)

#75 on the Shikoku Pilgrimage

www.waoe.org/steve/kagawa/mecca.html

Zentsuji, the birthplace of Kobo Daishi, is so named after the temple he built in 813. The temple’s main hall enshrines Yakushi Nyorai. It also houses 108 statues of the Rakan. The first statue of Yakushi Nyorai, reportedly carved by Kobo Daishi himself, was reduced to ashes in 1558. So were many of the 500 Rakan statues. The present Yakushi image carved by Uncho reportedly contains the remains of the first image inside it.

Photo at right courtesy of Bob March. Says Bob-san: “Outside of Takamatsu, Shikoku, is a temple called Zentsuji. There are many older wooden rakan inside the hondo (main hall) -- these statues perhaps date from the 16th or 17th century. Outside, around the perimeter of the temple grounds, are contemporary stone carvings of (at present) about 300 Rakan, which a nun told me were commissioned and donated by a Chinese shinja. They are the best rakan -- most individual, most full of humanity and humor -- I have seen (I’m comparing them to those at Rakan-ji in Meguro and at Eihei-ji in Fukui).

100 RAKAN 100 RAKAN

Shikoku Pilgrimage

On the pilgrimage route from temple #66 to #67 (Daikoji Temple), one passes between a 20-meter stretch lined with 100 stone Rakan statues.

500 Rakan at Gokurakuji Temple (Mihara, Japan)

photo by Dr. Gabi Greve

|

LEARN MORE

Theravada Organizations

Sutras & Sacred Texts

Photo Galleries & Temple Listings -- Arhat Art

Last Update June 2008

See Otagi Nenbutsu Temple

|

|