|

|

|

|

|

SHINTŌ GUIDEBOOK

Shintōism & Shintō Statuary

Native Animistic Religion of Japan

Shrine = Shintō, Temple = Buddhism

The community-based folk religion of Japan.

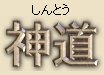

Belief in spirits who can bring both good and evil.

Belief that all natural objects are inhabited by spirits (kami 神).

Many Shintō deities in Japan incorporate Buddhist attributes.

Many Buddhist deities in Japan incorporate Shintō attributes.

The two are inexorably intertwined despite earlier efforts to divide them.

SHINTŌ. Japan’s indigenous folk religion can be traced back to at least the Yayoi 弥生 period (400 BC - 250 AD). The character SHIN 神 (also pronounced KAMI) is the generic term for god, goddess, divine spirit, and countless demonic and semi-benevolent nature spirits. The character TŌ 道 (also pronounced MICHI) means road, path, or way. Together, they are translated as WAY OF THE GODS (Kami no Michi 神の道). This guidebook presents a condensed tour of the most important Shintō concepts, deities, schools and sects, shrines, and other topics to help you better understand the beliefs, rituals, spiritual practices, and artwork of Japanese Shintōism.

WHAT IS SHINTŌ & SHINTŌISM?

Shintō (also spelled Shinto, Shintou). Also known as Kami-no-Michi 神の道 (the Way of the Gods). Shintō existed centuries before the arrival of Buddhism to Japan in the form of mountain shamanism and nature worship, but it had no written tradition, no centralized doctrine, no sculptural legacy. Indeed, modern scholars in Japan and the West insist that Shintō did not exist as an independent religion until the rise of modern nationalism in the early Meiji Period (1868-1912). In Japanese religious art, Shintō deities were not given anthropomorphic characteristics until the 8th century, about two centuries after the arrival of Buddhism. During Japan’s Heian era (794 - 1185), the numerous Shintō kami (deities) were recognized as traces or manifestations or incarnations (suijaku 垂迹) of the Buddhist divinities (honji 本地 or honjibutsu 本地仏), and a great syncretic melding occurred, with shrines and temples sharing both deities and sacred grounds. Even today, Shintōism remains unencumbered by religious doctrine and institutionalized belief, and serves more as a popular community-based folk religion featuring popular festivals, group pilgrimages, and special ceremonies to mark key life passages (e.g., birth, 7-5-3, coming of age, marriage). Shintō is a term created to distinguish itself (the indigenous religion) from Buddhism (an imported philosophy). Shintō's places of worship are called shrines, while Buddhist places of worship are called temples. Shintō deities are called KAMI 神, SHIN 神, JIN 神, SAMA 様, TENJIN 天神, GONGEN 権現, and MYŌJIN 明神 to distinguish them from their Buddhist counterparts. The latter are known as BUTSU 佛 and 仏 and NYORAI 如来 (all mean Buddha or Tathagata), BOSATSU 菩薩 (meaning Bodhisattva), TEN 天 (meaning Deva), MYŌ-Ō 明王 (meaning Luminescent Kings). See Terminology Page for more terms.

|

|

|

Shintō Menu

Shintō Intro

Schools & Sects

Shrines by Type

Inside the Shrine

Becoming a Priest

Deities (Kami) & Creatures

Festivals & Ceremonies

Sacred Sites

Terminology

Learn More

Resources listed at

bottom of each page

Shintō 神道. Also spelled

Shinto. Also known as Kami-no-

Michi 神の道 (Way of the Gods).

HIGHLIGHTS

Spirits, sacred incantations, and superstitions are the specialties of Shintō shrines, while sculpture and funeral rites are the forte of Buddhist temples. The lover of sculpture is therefore advised to plan accordingly.

The main Shintō rites and festivals are for celebrating the New Year, child birth, coming of age, planting and havest, weddings, and groundbreaking ceremonies for new buildings. Death, funerals, and graveyards involve Buddhist rituals, not Shintō. Most national holidays in modern Japan are Shintō in origin.

Unlike Buddhism, whose deities are generally genderless or male, the Shintō tradition has long revered the female element. The emperor of Japan, even today, claims direct decent from Amaterasu, the Shintō Sun Goddess.

In Japan today, Shintō and Buddhist practice among the common folk has taken on the air of “this-worldly benefits” (concrete rewards now; Jp. = 現世利益, Genze Riyaku). To many Japanese, Shintō and Buddhist faith is primarily involved with petitions and prayers for business profits, the safety of the household, success on school entrance exams, painless child birth, and other concrete rewards now, in this life.

Two of the 30 Kami of 30 Days

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HISTORICAL NOTES. Buddhism arrived in Japan around the 6th century AD from Korea and China along with Confucian and Taoist philosophies. Since then, Shintō belief and practice have interwoven intimately with these foreign influences. Today Shintō remains an extraordinary example of Japan’s penchant for religious syncretism. Despite aggressive government attempts to divide Japanese Buddhism and Shintōism into two distinct camps during the Meiji Period 明治時代 (1868-1912), the two continue to share both deities, sacred spaces, and concepts. Some of the most important centers of Buddhist-Shintō syncretism are the powerful Tendai temple-shrine multiplex on Mt. Hiei 比叡 (Shiga Prefecture, near Kyoto), the Shingon stronghold at Mt. Kōya 高野 (near Kyoto), the holy places throughout the Kumano 熊野 mountain range, the Kasuga 春日 shrine complex in Nara, and the many sacred mountains of Japan’s Shugendō 修験道 mountain cult, including Mt. Hakusan 白山 in northwest Honshū and Dewa Sanzan 出羽三山 in central Yamagata Prefecture. The native Shintō kami (deities) residing on these peaks were considered manifestations of Buddhist divinities, and pilgrimages to these sites were believed to bring double favor from both their Shintō and Buddhist counterparts. As one might expect, the number of deities in both camps proliferated. Despite earlier resistance, syncretism was relatively smooth and marked by religious tolerance. Shintō-Buddhist syncretism was actually formalized and pursued based on a theory called Honji Suijaku, with Shintō gods recognized as manifestations (suijaku) of the original Buddhist divinities (honji). In the later Kamakura period some Shintō sects proposed the opposite, proclaiming the Shintō gods as honji and Buddhist deities as suijaku.

|

|

Ceremony at Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine in Kamakura

No Sculptural Tradition. Shintō deities were not given anthropomorphic characteristics until the appearance of the court-sponsored Nikon Shoki 日本書紀 (Chronicles of Japan, also known as the Nihongi, released around 720 AD) and the Kojiki 古事記 (Records of Ancient Matters; Japan's oldest surviving text; 712 AD). The two were commissioned by Japan’s leaders to demonstrate to the Chinese Emperor that the Yamato Dynasty (aka Japan) had a long and distinguished history -- thereby proving that Japan was a sovereign kingdom. In the process, however, it appears that the creators of these documents made up the names of 28 Japanese sovereigns, starting with the first emperor, Jimmu Tenno (“he who ascended from heaven”). These 28 rulers are probably fictional, although there are many Japanese who will argue otherwise. No Sculptural Tradition. Shintō deities were not given anthropomorphic characteristics until the appearance of the court-sponsored Nikon Shoki 日本書紀 (Chronicles of Japan, also known as the Nihongi, released around 720 AD) and the Kojiki 古事記 (Records of Ancient Matters; Japan's oldest surviving text; 712 AD). The two were commissioned by Japan’s leaders to demonstrate to the Chinese Emperor that the Yamato Dynasty (aka Japan) had a long and distinguished history -- thereby proving that Japan was a sovereign kingdom. In the process, however, it appears that the creators of these documents made up the names of 28 Japanese sovereigns, starting with the first emperor, Jimmu Tenno (“he who ascended from heaven”). These 28 rulers are probably fictional, although there are many Japanese who will argue otherwise.

Prior to the Nihon Shoki and the Kojiki, there was no tradition of Shinto sculpture. The lack of Shintō sculpture until around the 8th century AD is in stark contrast to Buddhism. Buddhism originated in India around 500 BC, then found its way to Japan many centuries later via Korea and China. Under Buddhism, the artistic impulse of mainland Asia blossomed for nearly 500 years before reaching Japan. By the 6th century, when Buddhism finally arrives in Japan, the volume of Buddhist paintings, sculptures, and temples in India, Southeast Asia, Tibet, China, and Korea was already impressive. Confucianism failed to inspire any great schools of art in Japan (Taoist influences are instead given credit), nor did Confucianism become a religion or gain a religious following. Yet Confucianism without doubt greatly influenced social behavior.

|

NOT AN INDEPENDENT RELIGION NOT AN INDEPENDENT RELIGION

Shintō kami (deities) feature much less prominently than Buddhist deities in Japanese artwork and religious statuary. Shintō artwork is most often found in the combinatory Kami-Buddha art of the Shugendō mountain cults, and in the scroll paintings and mandala of the Tendai and Shingon sects of Buddhism There are a number of reasons for the lack of a vigorous Shintō artistic tradition. First, Shintō existed centuries before the arrival of Buddhism to Japan in the form of shamanism, nature worship, and mountain cults. But Shintō had no written tradition and no centralized doctrine until the emergence of Ise Shintō 伊勢神道, Ryōbu Shintō 両部神道 and Tendai Shintō 天台神道 in Japan's medieval period. It is only after the 13th century that one can speak with validity of a Shintō tradition (although many Japanese and Western academics, notably scholar Kuroda Toshio, insist that Shintō did not exist as an independent religion until the rise of modern nationalism in the early Meiji period). Second, Shintō deities were not given anthropomorphic characteristics until the 8th century, long after the arrival of Buddhism to Japan. Says JAANUS: "The first instance of making a kami image is believed to be that recorded in Tado Jingūji Garan Engi Shizaichō 多度神宮寺伽藍縁起資財帳 (Record of Properties of the Associated Temple of Tado Shrine), compiled in 801, which relates the story of how priest Mangan 満願 converted the kami of Tado to Buddhism in 763 and his subsequent portrayal of the kami in a sculpture. Thus, this artistic development appears to have occurred well after the introduction of Buddhism to Japan in the mid-6th century." The sculptural legacy and artistic output of Shintō has always paled in comparison to the Buddhist camp, and the Shintō art that survives today is predominantly representative of the Kami-Buddhist matrix that existed for centuries before Japan's Meiji government (1868-1912) forcibly separated the two religions and declared Shintō to be the main indigenous tradition.

Below text from Kokugakuin University: “Kuroda Toshio’s (1926-1993) seminal articles about Shintō brought the attention of a broad spectrum of Western scholars to a new understanding of the combinatory kami-buddha matrix (Shinbutsu Shūgō 神仏習合) and the role Shintō played in Japanese religious history (to the extent many modern scholars hesitate to employ the term ’Shintō‘ when discussing Japan’s religious history prior to mid 18th century). Kuroda’s writings deconstructed the term ’Shintō’ and insisted it did not exist as an independent religion until the rise of modern nationalism in the early Meiji period, specifically as the result of government policy to separate native beliefs from Buddhism (Shinbutsu Bunri 神仏分離). Until that time the religion and thought of the Japanese was characterized by orthodox Buddhist institutions (Kenmitsu Buddhism 顕密, or exoteric-esoteric traditions) which included Chinese-derived Yin-yang ideas and kami traditions. This, he insisted, was the ’comprehensive, unified, and self-defined system’ that prevailed in the pre-modern era (KURODA 1993, pp. 26-28). By presenting a paradigm that defined medieval religion as more than a collection of sects and schools, and moreover as a working combinatory model, Kuroda gave scholars the remit to investigate pluralities, as typified by Shugendō.” <end quote>

|

|

Shinto Overshadowed by Buddhism. The introduction of Buddhism to Japan immediately sparked the interest of Japan's ruling elite, and within a century Buddhism became the state creed, quickly supplanting Shintō as the favorite of the Japanese imperial court (Mahayana Buddhism was the form favored by the court). Buddhism brought new theories on government, a means to establish strong centralized authority, a system for writing, advanced new methods for building and for casting in bronze, and new techniques and materials for painting -- and it allowed Japan to gain the benefits of joining the larger cultural sphere of mainland Asia.

Greatly affected by the new religion, Japan’s Prince Shotoku (574-622 AD) institutionalized Buddhism as a state religion and built many great temples such as Horyuji in Nara Prefecture and Shiten'noji in Osaka. Many Buddhist temples today have a hall in which Prince Shotoku is enshrined in homage of his achievements. His portrait was printed, until recently, on Japan's 10,000-yen bills.

Wedded Rocks, due east of the Grand Shrines of Ise. Photo by Steve Beimel.

BLENDING OF SHINTŌ AND BUDDHIST TRADITIONS. By the 7th century, the Japanese court had aggressively accepted Buddhism, not only as a religious vehicle promising salvation for the upper classes, but also as an instrument to consolidate state power. Around the 8th century, Shintō traditions begin to imitate and blend with Buddhist influences. The Shintō-Buddhist syncretism of the period was actually formalized and pursued based on a theory called honji suijaku 本地垂迹. The process of blending Buddhism with Shintō progressed uninterrupted, and by the Heian Period (794-1185), Shintō deities came, among some Shintō sects, to be recognized as incarnations of Buddhist deities. One notable example is a syncretic movement that combined Shintō with the teachings of Shingon (Esoteric) Buddhism. This school believed that Shintō deities were manifestations (traces) of the Buddhist divinities. The Shintō sun goddess Amaterasu, for example, was identified with Dainichi Nyorai (the Great Sun Buddha).

Another major center of Shintō/Buddhist merging was the syncretic Tendai shrine-temple multiplex located at Mt. Hiei (Shiga Prefecture, near Kyoto), which came to prominence around the same time as Shingon Esoteric Buddhism. By the 9th century, Buddhist temples were constructed alongside Shintō shrines on many sacred mountains, epitomized by the powerful Tendai multiplex on Mt. Hiei and by the holy places throughout the Kumano mountain range. The native Shintō kami (deities) residing on these peaks were considered manifestations of Buddhist divinities, and pilgrimages to these sites were believed to bring double favor from both their Shintō and Buddhist counterparts. Another major center of syncretism was the Kasuga shrine (outside link) in Nara. The number of deities proliferated. Despite earlier resistance, syncretism was relatively smooth and marked by religious tolerance .

|

NOTE: The Tendai shrine-temple multiplex on Mt. Hiei is a prime example of the syncretic merging of Buddhist and Shintō deities in Japan. The idea of KAMI as Gohōjin 護法神 (guardian deities of the Buddhist doctrine) was a common element in the Heian period. This Shintō-Buddhist syncretism was actually formalized and pursued based on a theory called Honji Suijaku 本地垂迹, with the Buddhist deities regarded as the honji (original manifestation) and the Shintō kami as their suijaku (incarnations). Another similar term denoting the association between Buddha and Kami is Shinbutsu Shūgō 神仏習合. Furthermore, one resource identifies the "honji" of Sannō (Mountain King) as Ichiji Kinrin Butchō (the central Buddha of the "Court of the Perfected" (Jp. Soshitujibu). By the late 12th century, the Mt. Hiei shrine-temple complex formed a well developed honji suijaku 本地垂迹 complex, or syncretic merger of both Buddhist and Shintō practices and deities. NOTE: The Tendai shrine-temple multiplex on Mt. Hiei is a prime example of the syncretic merging of Buddhist and Shintō deities in Japan. The idea of KAMI as Gohōjin 護法神 (guardian deities of the Buddhist doctrine) was a common element in the Heian period. This Shintō-Buddhist syncretism was actually formalized and pursued based on a theory called Honji Suijaku 本地垂迹, with the Buddhist deities regarded as the honji (original manifestation) and the Shintō kami as their suijaku (incarnations). Another similar term denoting the association between Buddha and Kami is Shinbutsu Shūgō 神仏習合. Furthermore, one resource identifies the "honji" of Sannō (Mountain King) as Ichiji Kinrin Butchō (the central Buddha of the "Court of the Perfected" (Jp. Soshitujibu). By the late 12th century, the Mt. Hiei shrine-temple complex formed a well developed honji suijaku 本地垂迹 complex, or syncretic merger of both Buddhist and Shintō practices and deities.

|

Brief History of Shinto from Kamakura Era to Edo Era

In the Kamakura Period (1185-1333), Shintō was emancipated to some degree from Buddhist domination by Japan’s new military dictators (the Kamakura shogunate), and Shintō groups themselves proclaimed that Shintō divinities were not incarnations of the Buddha, but rather that Buddha himself was a manifestation of the Shintō deities. At the time, Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine (in Kamakura) was a notable example of both Shintō and Buddhism elements. It was a prime example of the syncretism of Yoritomo Minamoto (1147-1199), the founder of Tsurugaoka Hachimangu, and his claim to the lineage of the Imperial Family. Nevertheless, during this period, Buddhism was still the favorite of the ruling classes, and Shintōism did not grow in any appreciable form.

Buddhism itself experienced a flowering during the Kamakura Era, most notably with the emergence of new Buddhist sects determined to bring salvation to the illiterate commoner. Indeed, during the Kamakura Era, we see the emergence of three sects -- Nichiren, Jōdō, and Zen Buddhism -- each largely developing upon older Chinese teachings, each expressing concern for the salvation of the ordinary person, each stressing pure and simple faith over complicated rites and doctrines. Prior this this, Buddhism was almost exclusively the faith of the court and upper classes. The emergence of these new sects devoted to the commoner helped to popularized three Buddhist deities -- Amida Nyorai, Kannon Bosatsu, and Jizo Bosatsu -- Amida for the coming life in paradise, Kannon for salvation in earthly life, and Jizo for salvation from hell. Today, these three Buddhist deities still form the bedrock of Buddhism for the commoner. The trio are especially important to followers of Pure Land Buddhism. Kannon, meanwhile, holds an exalted status among followers of the Nichiren sect.

Shintō remained largely in the shadows until a small revival in the 17th century, when the Tokugawa Shogunate came to power. The new shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, tried to counteract the power of the Hongwan-ji Buddhist temples by reviving the Shintō faith. Nonetheless, by the Edo Period, when Japan turned inward, pursuing a policy of isolation from its neighbors that lasted nearly two centuries, Tokugawa’s small Shintō revival had fizzled out.

Small Shrine near Tokeiji Temple (Kita Kamakura)

Abolish the Buddha, Smash Shakamuni -- Meiji Era

Despite its reduced status at the imperial court between the 6th to 19th centuries, Shintō survived and thrived in the shadows of the Buddhist advance. When Shintō was co-opted by the Meiji rulers in the late 19th century, it quickly supplanted Buddhism. In line with government sponsorship and funding of State Shintō -- which emphasized emperor worship -- the Meiji government turned its ire on the powerful Buddhist monasteries. By decree, fiat, and force, the Meiji government proceeded to break up the great Buddhist estates. The powerful temples, forced by law to cut their Shintō ties, and harassed on all sides by new laws and estate taxes, were soon stripped of their lands and artistic treasures. Government attempts to destabilize Buddhism contributed to the anti-Buddhist riots of the late 1860s, when popular sentiment turned against Buddhism, portraying it as a foreign cult of corruption and decadence. In some areas, notably Satsuma, raging mobs burned down temples and decapitated statues. These anti-Buddhist riots are referred to as Haibutsu Kishaku 廃仏稀釈 (literally “Abolish the Buddha, Smash Shakamuni”).

Some lament the great pillaging and pilfering that occurred in the late Meiji period, when many wonderful temple treasures were sold off at rock-bottom prices, with many pieces finding their way into the hands of Western collectors and museums. The once-powerful Buddhist monasteries of Japan became mere shadows of their former selves. Much of their old-world glory was lost, sold to the cheapest bidder.

By the start of the Meiji Era (1868), Japan was forced to end decades of isolation. The “black ships” of Commodore Perry convinced the Meiji leaders to open Japan’s doors to Western culture, commerce, and technology. Japan enthusiastically entered a race to modernize and thus to block the colonization of its islands. As part of its modernization strategy, the Meiji government pursued a system of state-sponsored Shintōism focused on emperor worship. Emperor worship became the new state creed, and Shintōism was easily co-opted by the government and used to galvanize the nation into building a modern military, administrative, and educational state. This strategy, in their minds, required the forced separation of Shintōism and Buddhism. This in turn required the dismantling of Japan’s powerful Buddhist clans. For more on the dismantling of Japan’s Buddhist estates, please see:

"Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art"

by Ernest F. Fenollosa, published by ICG Muse Inc.

ISBN 4-925080-29-6. English. Originally published in 1912, but new edition in 2000. Perhaps one of the best books to date on Buddhist sculpture. Highly recommended.

After the Meiji Imperial Restoration of 1868, the Emperor regained imperial sovereignty (replacing the shogunate), and the new government institutionalized Shintō as the official state religion while implementing restrictive policies against Buddhism and other religions, including Christianity. Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine (in Kamakura) had to remove or thrown away all structures and objects associated with Buddhism. The Emperor turned living god, and those who dared to gaze directly at the divine Emperor were subject to arrest. Some critics say that wartime Japan was more fascist than today's North Korea, since Kim Jong Il was never divinitized. Today's emperor is no longer a god, of course, but the Japanese Constitution still defines the emperor as “symbol of the state and of the unity of the people.” Shintō, moreover, continues to this day to be the religion of the Imperial Family, and traditional Shintō rituals take place regularly in the Imperial Palace. The influence of this can be seen in Japan’s modern national holidays -- many originate in Shintō rituals. <above paragraph by Kondo Tadahiro>

In Japan today, both Shintō and Buddhist practice among the common folk has taken on an air of “this-worldly benefits” (concrete rewards now; Jp. = 現世利益, Genze Riyaku). To many Japanese, Shintō and Buddhist faith is primarily involved with petitions and prayers for business profits, the safety of the household, success on school entrance exams, painless child birth, and other concrete rewards now, in this life.

Sub-shrine with shimenawa (special plaited rope) and shime (strips of white paper)

BELOW COURTESY OF:

www.jinjapan.org/museum/shinto/about_shinto.html

Originally the Shinto tradition had no custom of making anthropomorphic images, but this was to a certain extent begun after the 8th century, in imitation of Buddhism and under the influence of the so-called honji suijaku theory of Shinto-Buddhist syncretism. Written records tell of Shinto images being carved in the latter half of the 8th century, but the earliest extant examples date from the 9th century (early Heian period). A feature distinguishing them from Buddhist images is the existence of both male and female images.

There is also a notable absence of set iconographic principles of the type which governed the production of Buddhist images. In many cases they are multicolored, and were made to imitate the clothing and hair styles of specific men and women of the court aristocracy of the time. Shinto images dating from the 9th century that were strongly influenced by contemporary Buddhist sculpture are found at Toji Temple in Kyoto, Matsunoo Taisha Shrine in Kyoto, and Yakushiji Temple in Nara. In the Kamakura period, several realistic and humanly appealing Shinto images were produced, including Kaikei's portrait sculpture of the Shinto deity Hachiman in the guise of a Buddhist monk (a noted example of Shinbutsu Shūgō 神仏習合, or blended Shinto and Buddhist iconography) at Todaiji Temple in Nara, and the portrait of Tamayorihime-no-mikoto (aka Tama Yori Hime no Kami) 玉依姫神 found at Yoshino Mikumari Shrine in Nara Prefecture.

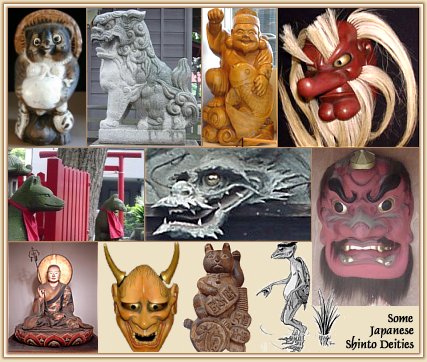

Roof of Shinto Shrine in Yamanakako

with Buddhist symbol at apex; this symbol means

the shrine follows both Shinto and Buddhist traditions.

卍

卍 is a symbol originating in India. Known as the Kyoji 胸字 (Kyōji) in Japan. Found frequently in India on the chest of Lord Vishnu. In Japan it is used as a symbol of Buddhist faith, one found frequently on statues of the Buddha (Jp. = Nyorai 如来) and Bodhisattva (Jp. = Bosatsu 菩薩), and one of the 32 Marks of the Buddha (Sanjūnisō 三十二相). It represents the ”possession of all virtues” in Japanese Buddhism. See Footprints of Buddha for more.

Ryōbu Shintō 両部神道

Meaning = Dual Shintō. This is a term used to refer generally to Shintō as syncretized with Buddhism, and specifically to that syncretic Shintō as interpreted by Shingon Buddhism (see Shingon Shinto below), in contrast to Tendai Shinto. If the shrine has a plaque on it’s gate, it is Ryōbu Shintō, which means Shintō influenced by Buddhism. Because Buddhism and Shintō have coexisted in Japan for hundreds of years, they have had strong influences on each another, even lending each other gods, and altering the way each is practiced.

Shingon Shintō

Also called Ryōbu Shintō, an interpretation of Shintō according to the doctrines of the Shingon sect of Buddhism. In the esoteric Shingon sect, the unity of the metaphysical world with the phenomenal and natural world is explained via the dualistic principles of the Kongokai (vajradhatu or diamond world) and Taizokai (garbhadhatu or womb world). See Ryōkai Mandala for many more details. According to this interpretation, the relative is equivalent to the absolute and phenomenon is equivalent to noumenon. This principle was extended to assert that the native Japanese deities are equivalent to the Buddhist deities; for example, Amaterasu Omikami is viewed as equivalent to Dainichi Nyorai (Mahavairocana). This school of thought was said to have been initiated by Kūkai 空海 (774 - 835 AD), the founder of the Shingon sect of Esoteric Buddhism in Japan, but it is in fact a later development. Kūkai was, however, a strong believer in Shintō deities, and established the shrine Nibutsuhime Jinja as the tutelary deity of Kōyasan, the mountain monastery which he founded. Other terms for the blending of Shintō with Buddhism are honji suijaku and shinbutsu shugo.

Honjisuijaku or Honji-suijaku Setsu 本地垂迹

Theory of original reality and manifested traces. A theory of Shintō-Buddhist syncretism. Originally a Buddhist term used to explain the Buddha's nature as a metaphysical being (honji) and the historical figure Sakyamuni (suijaku). This theory was used in Japan to explain the relation between Shintō gods and Buddhas; the Buddhas were regarded as the honji, and the Shintō gods as their incarnations or suijaku. Theoretically, honji and suijaku are an indivisible unity and there is no question of valuing one more highly than the other; but in the early Nara period, the honji were regarded as more important than the suijaku. Gradually they both came to be regarded as one; but in the Kamakura period, Shintōists also proposed the opposite theory, that the Shintō gods were the honji and the Buddhas the suijaku. This theory is called han-honji-suijaku setsu or shinpon-butsuju setsu.

GONGEN 権現

Meaning: Avatar, or Shinto Kami as Manifestations of Buddhist Deities

More on Honji Suijaku 本地垂迹

Ancient Shintō did not bother to erect shrines until the 3rd and 4th century. Not until the country was unified under the Yamato in the 4th century did Shintō begin to acquire a general hierarchical structure with the Yamato gods at top and local gods at bottom. The first known Japanese histories were efforts to legitimize the imperial line by merging myths and legends concerning local ujigami with the Yamato mythology. No Shintō doctrine as such, however, was postulated until the mid-Heian HONJISUIJAKU doctrine stipulating that Shintō gods were really manifestations of Buddhist deities, thereby linking indigenous beliefs to Buddhist teachings.

In feudal and early-modern periods, a number of sects emerged professing an independent and pure Shintōism, including Ise, Yoshida, and Fukkō Shintō. But in Meiji period, the government made determined efforts to promote emperor worship and all the trappings of Shintō, so local shrine teachings and festivals were brought into line with the national doctrine, and local priests lost the authority to do much except conduct ceremonies.

Shinbutsu Shūgō 神仏習合

The harmonization of Shintō, the native Japanese religion, with Buddhism, which came from India to Japan via Korea and China. According to Buddhist doctrine, a person who has done good may become a deva after death, living in heaven, encouraging humans to do good, and acting as a protector of Buddhism. When Buddhism was introduced to Japan (around 538 AD, other sources say 552 AD), the word deva was translated in Japanese not only as Ten 天, but also as kami, in order to facilitate the propagation of the new religion among the common people. This process of syncretization became particularly conspicuous during the Nara period. Before constructing the Big Buddha at the Tōdaiji in Nara (741), Emperor Shōmu 聖武 (reigned +724 to 749) first commanded the Priest Gyoki to report the plan to the goddess at Ise no Jingu and to make an offering of relics of the Buddha; Buddhist scriptures were also offered to the Usa Hachiman Shrine. Syncretic practices such as building shrines on temple grounds and pagodas in shrine precincts, and of reading Buddhist scriptures before Shintō deities or presenting them to shrines, all continued until the two religions were forcibly separated in the early Meiji period (shinbutsu bunri 神仏分離). The theory of honji suijaku was developed during the Heian period to explain this relationship and propagated through such movements as Shingon Shintō and Tendai Shintō. Shinto develops close ties with Shingon and Tendai Buddhism during the Heian period.

いわしの頭も信心から (いわしのあたまもしんじん)

Even the Basest Thing is Sacred

SHINTO HISTORY

Below Text Courtesy of Kondo Tadahiro

http://www.asahi-net.or.jp/~QM9T-KNDU/shintoism.htm

Used with permission. This abridged version includes some interesting comments about corruption within modern Shinto.

Shinto is native to Japan, its roots stretching back to 500 BC. It is a polytheistic faith that venerates almost any natural object, ranging from mountains, rivers, water, rocks, trees, to dead notables. In other words, it is animism. Natural wonders make the Japanese believe, out of awe or reverence, that such wonders are created by a mighty, supernatural power(s), and that the spirits of deceased beings dwell in such objects. Also great warriors, leaders and scholars are often divinized. Thus anything, even the rotten head of a sardine, can be deified (so goes a cynical saying). To dedicate to those diverse deities, shrines were erected in a sacred spots throughout Japan. Among natural phenomena, the sun is most appealing to the Japanese, and the Sun Goddess is regarded as the principal deity of Shinto, particularly by the Imperial Family. We Japanese call our nation “Nippon” in Japanese. It literally denotes ”the origin of the sun.” The Japanese national flag is simple, one red disk in the center, and it symbolizes the sun.

According to Japanese mythology, the goddess of the sun and the ruler of heaven is named Amaterasu, and she is believed to be the legendary ancestor of the current Imperial Family. Legend asserts that she was once so offended by the misdeeds of her brother that she came down to the earth and hid in a cave. The universe was plunged into pitch darkness and evil thrived. The gods and goddesses gathered near the cave to talk about how to get her out. They held a party and a goddess began to dance in front of the cave, causing the crowd to roar with delight. As she whirled about, her clothes fell off, drawing cheers from the other gods. Curious about the fuss, Amaterasu peeked out from behind a giant rock blocking the cave's entrance. The dancing goddess held up a mirror and said, "We are dancing to celebrate the new goddess." Amaterasu came out to see the new goddess, but what she saw was her own reflection. A powerful being grabbed her out and told her never to hide again.

The emperor of modern Japan is Emperor Akihito, who is said to be the 125th direct descendant of Emperor Jinmu, Japan's legendary first emperor and a mythical descendent of Amaterasu. Though not often referred to today, the Japanese calendar year starts from 660 BC, the year of his accession. The reigning emperors since then are considered to be the direct descendants of the Sun Goddess and are revered as living gods. When the Pacific War was imminent in 1940, the fascist government even boasted that it was the year 2600, to exalt the national prestige, and it even made a song cerebrating the 2600th year.

Shinto Priests at Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine in Kamakura

In general, Shinto has no canon or written scriptures like the Bible or the Koran, although ceremonial prayers -- called norito (a formulary statement addressed to the deity) -- are chanted by shrine priests. The scholar Motoori Norinaga says that “norito” are sacred incantations by which humans can address the gods, while others say norito are commands issued by the gods to humans. Most Shinto shrines house sacred objects such as mirrors (the symbol of the Sun Goddess), swords and jewels (those three objects are the imperial regalia) on the altar where the gods are believed to reside, and the objects serve as spirit-substitutes for the gods.

Shinto is also, generally speaking, the religion of rituals and ceremonies for purification and exorcism, which can often be observed among Japan’s corporate groups. Whenever a new factory manager is appointed, for example, he traditionally has to visit three places -- (1) mini-shrine installed at a cozy corner of the factory grounds, where he says a prayer for safety during his term of office; (2) must go to central labor union of factory to say hello and; (3) must visit local fishermen’s association, as factories are usually located near the seacoast and likely to pollute the seawater with effluent.

At the ground-breaking ceremony or at the start-up of a new facility, be it a high-tech or a smoke-stack industry, a Shinto priest is always invited to perform the purification and exorcism rituals. Those are common Shinto-related customs practiced at any manufacturing plant in Japan. In the case of Toyota Motors, for example, top executives play out corporate rituals every autumn at the Ise Shrine in Mie Prefecture, the spiritual home of the Sun Goddess Amaterasu -- here they unveil their newest models, making the three-hour drive from their headquarters near Nagoya. Shinto is thus firmly embedded in today's corporate society.

The Yomiuri Shimbun, a leading daily newspaper in Japan (circulation around 10 million), once reported that a bogus organization billing itself as an association of Shinto priests, made a lucrative business out of sending retired workers disguised as priests to new building sites in Tokyo to conduct ground-breaking ceremonies. The fake priests were dispatched on hundreds of occasions over three years, charging 40,000 yen per visit (each visit lasting only an hour or so). Of the 40,000-yen payment, the “priest” earned about 10,000 yen, with the group receiving the remainder. To work officially as a priest, an individual must receive an appointment from the “Association of Shinto Shrines,” and yet there is no certification or qualification system.

We sometimes see the raging controversy over the governments' attitude toward Shinto when they followers donate money to shrines as offerings. A prefectural governor once paid 166,000 yen of taxpayers' money on 22 occasions between 1981 and 1986 to Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, which enshrines Japan's 2.6 million war-dead, including World War II Class-A criminals such as the wartime prime minister. The payments were made to cover the Tamagushi fee. Tamagushi is a sprig of Cleyera orchnacca with attached white paper-strips (called ”shide”), used by Shinto priests at ceremonies. A citizen's group filed a lawsuit in 1982 against the governor, charging that the payment of public funds to the Shinto shrine was unconstitutional. Article 20 of the Constitution stipulates that the state and its organs shall refrain from religious education or any other religious activity. A lawyer for the defendants said that the small cash offerings to the shrine represented condolences and were a “humanitarian courtesy” to the 2.6 million war-dead. In April 1997, Japan’s Supreme Court ruled that the donation violated the Constitution. The ruling was supported by 13 judges of the 15-member Grand Bench of the Supreme Court. <end quote by Kondo Tadahiro>

ō Ō ō Ō

|

|