|

|

|

|

|

|

36 pages. This annotated narrative is based on extant Tanuki art (175 photos herein). It describes, both chronologically and thematically, the metamorphosis of the spook-beast Tanuki from a bad guy to good guy, from feared to beloved. It also debunks widespread misinformation about Tanuki. It is intended as a "primer" for students and teachers of art history and folklore.

|

|

|

|

|

|

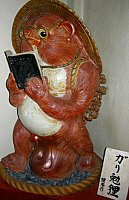

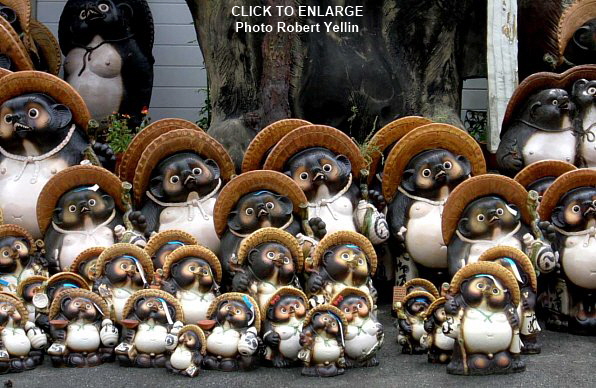

Tanuki, modern, ceramic. Sake Kai Tanuki 酒買狸 (lit. Tanuki Procuring Sake). Depicted with big tummy, staff, giant scrotum, straw hat, sake flask, and promissory note. Welcoming icon found frequently outside Japan’s bars and eateries (“come in, don’t be stingy”). Also a wealth-bringing icon adorning gardens.

Photo from Rakuten J-store

|

|

|

|

TANUKI MENU

|

|

|

|

Mythical versus Real Tanuki

Mistranslations, Confusing Names

Fox / Tanuki Lore in Old China

Fox / Tanuki Lore in Old Japan

17th Century Tanuki Art in Japan

18th Century Tanuki Art in Japan

19th Century Tanuki Art in Japan

20th Century Tanuki Art in Japan

|

|

|

|

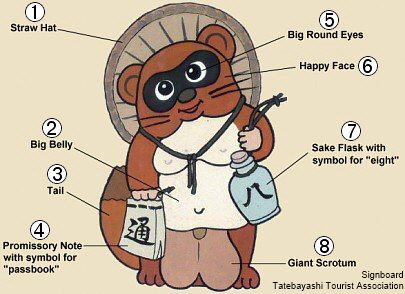

TANUKI ATTRIBUTES

|

|

|

|

Tanuki’s Main Attributes

Big Belly & Belly Drumming

Origins of Big Belly & Drumming

Big Scrotum (aka Money Bags)

Leaf, Umbrella, Straw Hat

Sake Flask and Hachi (Eight)

Promissory Note It Never Pays

Under the Moon, Howling

Disguised as a Buddhist Monk

Tanuki Masks for Kyōgen Plays

Modern vs. Traditional Tanuki

|

|

|

|

TANUKI TALES, OTHERS

|

|

|

|

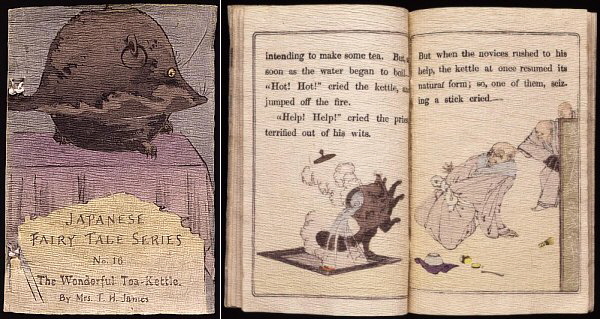

Bunbuku Chagama (Teapot) Tanuki

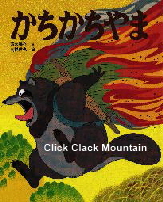

Kachi Kachi Yama & Rabbit

Danzaburō, Hage & Shibaemon

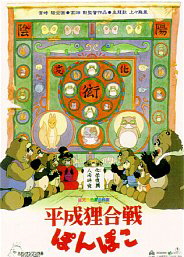

Heisei Tanuki Gassen Ponpoko

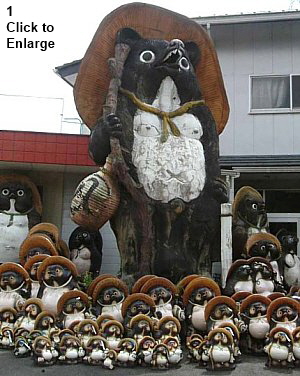

Shigaraki Ceramics & Tanuki

Badger Lore in China & Japan

Sources: Primary // Secondary // Misc.

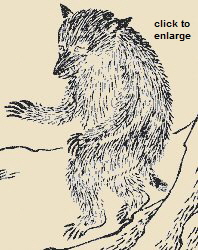

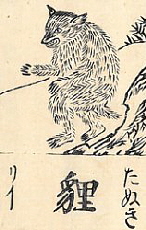

Tanuki standing on hind legs,

from the Kinmōzui 訓蒙圖彙 illustrated Japanese encyclopedia dated to 1666.

|

|

|

|

TANUKI’S NAMES & FORMS

|

|

|

|

Anaguma 穴熊 (badger)

Araiguma 洗熊 (racoon)

Bakedanuki 化け狸 (shape-shifter)

Bai 霾 (rain 雨 + Tanuki 貍)

Furudanuki 古狸 (old tanuki)

Iwadanuki 岩狸 (hyrax)

Kan 貛 (badger)

Kodanuki 小狸 (small tanuki)

Kokkuri 狐犬狸 (lit. fox, dog, tanuki)

Kori 狐狸 (lit. fox & tanuki)

Kōri 香狸 (civet)

Mameda 豆狸 (bean-loving tanuki)

Mamedanuki 豆狸 (small tanuki)

Mami 貒・猯 (tanuki or anaguma)

Midanuki 貒狸 (badger)

Mujina 貉・狢 (fox-like beast)

Ōkami 狼 (wolf)

Sai 豺 (mountain dog)

Tanuki 貍、狸、たぬき、タヌキ

Ya-byō, Ya-myō 野猫 (field cat)

Yūri 狖狸 (weasels & tanuki)

More Details Here

|

|

TANUKI 狸・貍, MUJINA 狢・貉, MAMI 猯・貒

Magical Fox-Like Dog with Shape-Shifting Powers

Trickster & Spook, Originally Evil, Now Benevolent

Modern-Day Icon of Generosity, Cheer, and Prosperity

Found Often Outside Japanese Bars & Restaurants

Most Images Can be Enlarged by Clicking

ORIGIN = Chinese Fox Lore + Japanese Accretions

Overview

The magical shape-shifting Tanuki is clearly a composite creature. The original evil parts come from old China and its fox lore (introduced to Japan between the 4th-7th centuries CE). The newer tamer parts, such as the big belly, belly drumming, giant scrotum, and sake bottle can be traced to late Edo-era Japan (18th-19th centuries), while the commercialized benevolent parts (promissory note, straw hat) emerged in Japanese artwork around the beginning of the 20th century. In general, the goofy-looking Tanuki we are familiar with today is a recent creation, mostly Japanese. But by carefully investigating Tanuki’s remote origins from China, we can demarcate original property from borrowed property. This endeavor, in my mind, leads to a greater appreciation of Japan’s penchant for creating imaginative, playful, and endearing myths. The Chinese influence on Japanese folklore, without doubt, is enormous. Yet the Japanese are equally adept at creating their own lore, as exemplified by their homespun Tanuki legends.

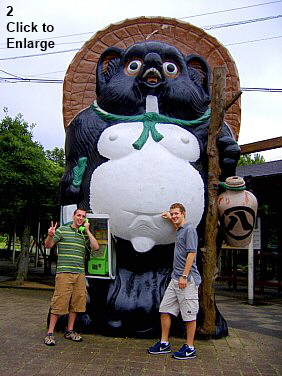

Mythical & Magical Tanuki

The fox-like Tanuki appear often in Japanese folklore as shape-shifters with supernatural powers and mischievous tendencies. In their earliest malevolent manifestations (transmitted via Chinese fox lore to Japan by at least the 7th century CE), Tanuki assumed human form, haunted and possessed people, and were considered omens of misfortune. Many centuries later in Japan, they evolved into irrepressible tricksters, aiming their illusory magic and mystifying belly-drum music at unwary travelers, hunters, woodsmen, and monks. Today, the Tanuki are cheerful, lovable, and benevolent rogues who bring prosperity and business success. For more on Tanuki’s metamorphosis from bad guy to good guy, see Tanuki Origins. Ceramic statues of Tanuki are found everywhere in modern Japan, especially outside bars and restaurants, where a pudgy Tanuki effigy typically beckons drinkers and diners to enter and spend generously (a role similar to Maneki Neko, the Beckoning Cat, who stands outside retail establishments.) In his modern form, the fun-loving Tanuki is commonly depicted with a big tummy, a straw hat, a bewildered facial expression (he is easily duped), a giant scrotum, a staff attached to a sake flask, and a promissory note (that he never pays). Many of these attributes suggest his money was wasted on wine, women, and food (but this is incorrect; see below). More surprisingly, most of these attributes were created in very modern times (in the last three centuries; see Tanuki in Modern Times). Although the Japanese continue to classify Tanuki as a yōkai 妖怪 (monster, spirit, specter, fantastic/strange being), the creature today is no longer frightening or mysterious. Instead, it has shape-changed into a harmless and amusing fellow, one more interested in encouraging generosity and cheerfulness among winers and diners than in annoying humankind with its tricks. Tanuki are also portrayed as cute and lovable characters in modern cartoons and movies -- even as mascots in commercial campaigns. For instance, the former Tokyo-Mitsubishi Bank not long ago used the Tanuki (and a Kappa river imp) to promote its DC credit card (a campaign since ended). These topics are explored below.

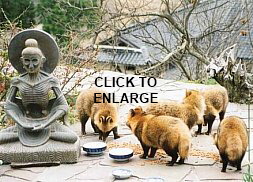

Real Life Tanuki

The Tanuki is also a real animal. It is often confused with the badger (ana-guma) and the raccoon (arai-guma). It is neither -- it is an atypical species of dog that can grow up to 60 cm. in length, with distinctive stripes of black fur under its eyes. In old Japan, Tanuki were hunted for their meat (reputed to have medicinal qualities), their fur (used for brushes and clothing) and their scrotal skin (used as a malleable sack for hammering gold into gold leaf). They live in burrows, and come out after sunset until the wee hours of the morning. Says the Yamasa Institute, Center for Japanese Studies Newsletter (Sept. 15, 2001): “As tanuki have moved into suburban and even urban areas in Japan during the 1980s and 1990s, they have taken to feeding at rubbish dumps and are even fed by local people in their gardens, which is one reason why they are associated with racoons who thrive on the rubbish littering many cities.....the future of the Tanuki [in Japan] is uncertain as many are afflicted with sarcoptic mange, a condition caused by a parasitic mite.” <end quote> Today (Oct. 16, 2011) I spoke with a representative of a cat-lovers group from Yokohama, one helping to find homes for stray cats, and she said many tanuki now inhabit the area, many steal the food set out for the cats, and many suffer from mange. To help the suffering tanuki, they inject a sweet bread with medicine (a bread the cats will not eat) and mix it together with food for the cats. This strategy has cured “a few tanuki” of mange. The Tanuki is reportedly native to Japan, southeastern Siberia, and Manchuria. Some were introduced to western parts of the Soviet Union for fur farming in the 1950s, and have since spread into Scandinavia and as far south as France. Scientific Name: Canis Procyonoides, Canis Viverrinus, Nyctereutes Procyonoides. Belongs to dog family. Canini (related to wolves) and Vulpini (related to foxes). See Tanuki Fact Sheet.

Mistranslations of Tanuki

Confused Naming Conventions

Neither the badger nor the racoon (raccoon) figure prominently in Chinese or Japanese folklore or artwork. Nonetheless, for decades, Western scholars have mistranslated Tanuki as “badger” or “racoon-dog.” This is clearly wrong, but can be forgiven -- the Tanuki does, in fact, look badger-like, racoon-like, and fox-like. Furthermore, such mistranslations are compounded by the Japanese themselves, who have likewise confused these animals in their folklore and artwork. For all practical purposes, the moniker “TANUKI” includes other similar creatures like the badger, racoon, the mujina 貉 and mami 貒 (other names for Tanuki in some Japanese localities), wild mountain dogs and cats, and most other fox-like creatures. This confusion is sometimes the source of great amusement. In Tochigi Prefecture, for example, the Tanuki is called “Mujina.” In 1924, in the so-called Tanuki-Mujina Incident たぬき・むじな事件, Tochigi authorities prohibited the hunting of Tanuki and promptly arrested one hunter -- who claimed he was out hunting mujina. The man was taken to trial, but eventually acquitted (on 9 June 1925). His defense argued that hunting of “mujina” was not prohibited by law, that the hunter’s intention was to pursue mujina, and therefore, by law, he was not guilty of any offense. In Japan’s northern Kanto region, Tanuki is known as MUJINA. In the Tokyo area, the creature is called MAMI. In the Kinki region (around Osaka), the beast is referred to as TANUKI. <Source: National Institute of Japanese Literature, Mitsuru Aida>

PHOTOS LEFT TO RIGHT. (1) Real Tanuki in garden of Gabi Greve (Japan); (2) Real Baby Tanuki, photo Adam Nuelken;

(3) Mammalian Species, Tanuki Fact Sheet, by the American Society of Mammalogists #358 (1987-1991)

|

ORIGIN = Fox and Tanuki Lore in Old China

|

|

Japan’s Tanuki lore clearly sprang from the same page as China’s earlier fox mythology (see Table 1). Fox lore in China is ancient and voluminous, while Tanuki lore is almost non-existent. China’s vulpine lore is also complex. The ill-boding evil fox is mentioned early on by the Chinese sage Zhuāngzí / Chuang-tzu 莊子 (369-286 BC; Jp. = Sōshi). [need citation] Chinese texts from the 3rd century AD onward speak frequently of foxes as spook-beasts causing insanity, disease, and death, of possessing and bewitching both men and women, of hypnotizing people and leading them into perilous situations, and of shape-shifting into human form (typically a were-vixen) to carry out their unprovoked malignity. Foxes grow in power as they age. They grow a tail for each century of life. When they reach 900 years of age, a nine-tailed fox 九尾狐 gains the power of infinite vision (in some texts, the creature is a good omen, in others a bad omen). Foxes who live to be 1,000 years or older are called Celestial Foxes 天狐 and no longer haunt mankind. The shape-shifting power of the fox is not perfect. While transformed, the fox is susceptible to the same pressures and natural predators faced by the form it assumes. Foxes were much persecuted in old China, mostly by smoking them out of their burrows (often located in caved-out old graveyards). This prompted Chinese authorities to forbid smoking foxes out of graveyards. Similar laws were later enacted in Japan during the reign of Emperor Mommu 文武 (697-707). Promulgated in 702 in Section VII of the Zokutō Ritsu 賊盗律 (Laws Concerning Robbers), these edicts warned against "smoking foxes and tanuki (Jp. = Kori 狐狸) out of graves.” The term Kori 狐狸 comes from earlier Chinese texts, in which the characters for fox 狐 and tanuki 狸 were combined 狐狸. However, in China, the combined term means “foxes” only. Early references to 狐狸 are found in the Sōushénjì 搜神記 (Sheu Shen Ki), a 4th-century Chinese document attributed to Gan Bao 干寶 (fl. 317-322). This usage (limited to the fox) is substantiated by the near-absence of Tanuki lore in China. <sources: De Groot, p191 & De Visser, p1>

|

|

From China’s 1610 Sansai-zue

illustrated encyclopedia.

PHOTO: this J-Site

|

From Japan’s 1666

Kinmōzui illustrated encyclopedia. PHOTO: this J-site

|

From Japan’s 1715 illustrated

Wakan Sansai-zue encyclopedia.

PHOTO: this J-site.

|

|

|

Photos at left and right

Parcel-gilt silver dish with animal design. D = 22.5 cm, H = 1.5 cm. 8th century, China. Shaanxi Historical Museum. Photo from exhibition catalog (p. 219) entitled Treasures of Ancient China, Oct. 24 - Dec. 17, 2000, Tokyo Nat’l Museum, Published by Asahi Shimbun. The catalog notes the “fox-like” features, but says the head and ears differ from those of real foxes. Perhaps this is an early Chinese example of the magical fox-like Hó 貉 (Jpn. = Mujina). See below for 17-century Japanese depiction of a Mujina.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TABLE 1 - Comparing Fox-Tanuki Lore in China & Japan

The Chinese fox predates the Japanese Tanuki by many centuries. Japan’s Tanuki

clearly derives from the same page as China’s fox. Below items listed in no particular order.

|

|

= Yes, = Yes,  = No = No

|

China

Fox

|

Japan

Fox

|

Japan

Tanuki / Mujina

|

NOTES

|

|

can possess people

|

|

|

|

Fox possession (kitsune tsuki 狐憑き); fox bewitchment (kitsune damashi 狐だまし

|

|

haunts houses, locations

|

|

|

|

live in caved-out graveyard plots and burrows

|

|

can shift into male, female,

inanimate forms (Buddha, Bosatsu, monk, nun, teapot)

|

|

|

|

fox / tanuki normally shift into female form,

but tanuki are less adept and instead often shift

into inanimate shapes, like a tea pot

|

|

often assumes form

of beautiful woman

|

|

|

|

their evil nature represents YIN; therefore they

shape-shift into forms to atttract YANG (male)

|

|

gains power as it ages

|

|

|

|

the older, the more powerful

|

|

both good and bad

|

|

|

|

mostly evil in China, albeit a few exceptions

|

|

dogs are mortal enemies

|

|

|

|

common dogs can kill fox, mujina, and tanuki

|

|

holds / possesses jewel

|

|

|

|

in the Japanese Nihongi, mujina has jewel in belly

|

|

needs object to transform

|

|

|

|

fox = human skull & bones; tanuki = leaves

|

|

nocturnal

|

|

|

|

moon is a common theme in tanuki artwork

|

|

howling is bad omen

|

|

|

|

in a few cases, howling is considered good

|

|

turns pebbles into gold

turns dung into food

|

|

|

|

both the fox & tanuki can cast powerful illusions

and create mirages of markets, cities, & palaces

|

|

sees future, its own death

|

|

|

|

can portend future events, both human & spirit world

|

|

eating its flesh cures

ulcers and other problems

|

|

|

|

fox = flesh cures ulcers, liver revives the dead, blood refreshes the drunk; tanuki meat cures piles & ulcers

|

|

gains tail as it ages

|

|

|

|

fox gains a tail for every 100 years of age

nine-tail fox is all powerful and a good omen

|

|

divine connection

|

|

|

|

in Japan, the fox is a messenger of Inari (rice kami)

|

|

can breed with humans

|

|

|

|

in Japan, Tanuki have fewer powers than foxes

|

|

can conjure fire & lights (infitur ignitus)

|

|

|

|

will-o’-the-wisps; fox fire (Kitsune-bi), tanuki fire (Tanubi-bi), perhaps due to their eyes shining in dark

|

|

SOURCES: Numerous Chinese and Japanese documents (see Resources), extant Japanese artwork (as appearing within this story), and English resources such as De Visser (1908) // Violet H. Harada (1976) // U.A. Casal (1959).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fox and Tanuki Lore in Old Japan

|

|

|

|

Two fox guardians at Inari Shrine

just outside Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine in Kamakura.

Tanuki, Kyokutei Bakin’s 曲亭馬琴

(1767-1848) Enseki Zasshi 燕石雑志.

Digital version at Waseda Library.

Jump directly to digitized photo.

Jump directly to Tanuke 田之怪 text.

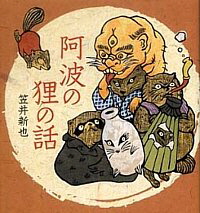

Book cover. Stories of Tanuki in Awa Province (Awa no Tanuki no Hanashi 阿波の狸の話), by Kasai Shin'ya 笠井新也. First published in 1927 (Chūkōbunko 中公文庫). Modern-day reprints available at Kinokuniya Bookweb. Among the various images of Tanuki on this book cover, we see the one-eyed Tanuki who can produce thunder.

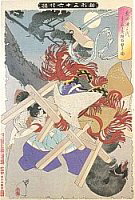

Flying-Dragon Tanuki 飛龍狸 (in red robe) Battles 9-Tailed White Fox 白九尾の狐. From a mid- 20th-century Kami Shibai 紙芝居 (Paper Theatre Drawing). Photo Tokyo Metropolitan Library. For more details about this drawing, see below.

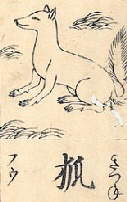

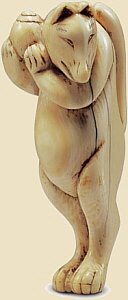

Fox (or a Tanuki or Mujina?).

Holding jewel. Unsigned ivory netsuke. Early 19th century. H = 6.5 cm.

Its bulging stomach suggests

a Tanuki / Mujina. Photo from

Scholten Japanese Art

|

|

|

As Table 1 above shows, Japan’s tanuki lore was derived predominantly from China’s fox lore, although the Japanese did add a “divine” connection between their fox and their local kami (deity) of rice, Inari. This gives the fox a dual character in Japan -- both evil and sacred. This dichotomy is not found in China, where the fox is mostly evil. Second, in Japan, Tanuki are portrayed as less adroit, less clever, and less dignified than foxes, no doubt reflecting the fox’s divine association with Inari (from around the 11th century onward, Inari was portrayed alongside white foxes or atop a white fox). Unlike the fox, the Tanuki was also given a humorous side -- he often appears as a clever schemer, but is easily outwitted and duped. Third, Tanuki were not even mentioned in Japan’s earliest documents (8th century) -- they appear much later, in the 13th-century Uji Shūi Monogatari 宇治拾遺物語 (where a tanuki shape-changes into Fugen Bosatsu but is eventually discovered and killed) and the 14th-century Nichū Reki 二中暦 (a Japanese zodiac calendar wherein the tanuki, mujna, and fox are listed among the 36 animals of Zodiac Calendar (Chikusan Reiki 畜産暦). In fact, it is the fox-like Mujina (conflated with Tanuki) who comes first to Japan. Unlike foxes, who appear often in Japanese texts from the 8th century forward, the mujina are only mentioned twice in the Nihon Shoki 日本書紀 (Japan’s oldest text, also known as the Nihongi or Chronicles of Japan, circa 720 AD). Moreover, for reasons unknown, the mujina disappear from Japanese literature after the 8th century and do not reappear until the 18th, when they are conflated with (by then) the popular Tanuki. As Table 1 above shows, Japan’s tanuki lore was derived predominantly from China’s fox lore, although the Japanese did add a “divine” connection between their fox and their local kami (deity) of rice, Inari. This gives the fox a dual character in Japan -- both evil and sacred. This dichotomy is not found in China, where the fox is mostly evil. Second, in Japan, Tanuki are portrayed as less adroit, less clever, and less dignified than foxes, no doubt reflecting the fox’s divine association with Inari (from around the 11th century onward, Inari was portrayed alongside white foxes or atop a white fox). Unlike the fox, the Tanuki was also given a humorous side -- he often appears as a clever schemer, but is easily outwitted and duped. Third, Tanuki were not even mentioned in Japan’s earliest documents (8th century) -- they appear much later, in the 13th-century Uji Shūi Monogatari 宇治拾遺物語 (where a tanuki shape-changes into Fugen Bosatsu but is eventually discovered and killed) and the 14th-century Nichū Reki 二中暦 (a Japanese zodiac calendar wherein the tanuki, mujna, and fox are listed among the 36 animals of Zodiac Calendar (Chikusan Reiki 畜産暦). In fact, it is the fox-like Mujina (conflated with Tanuki) who comes first to Japan. Unlike foxes, who appear often in Japanese texts from the 8th century forward, the mujina are only mentioned twice in the Nihon Shoki 日本書紀 (Japan’s oldest text, also known as the Nihongi or Chronicles of Japan, circa 720 AD). Moreover, for reasons unknown, the mujina disappear from Japanese literature after the 8th century and do not reappear until the 18th, when they are conflated with (by then) the popular Tanuki.

The fox’s divine connection to Inari (Japan’s god of rice) is hard to discern, but the most accepted theory today involves Japan‘s Yama-no-Kami 山の神 (mountain deity) and Ta-no-Kami 田の神 (rice-paddy deity). In Japanese folklore, the mountain kami was believed to descend from its mountain residence in the winter to become the rice-paddy kami in the spring, residing there throughout the growing season. After the fall harvest, the deity returned once again to its winter home in the mountains. All this probably took place at the same time that foxes appeared each season. As such, the fox naturally became known as the messenger of Inari. <See Kokugakuin University’s Encyclopedia of Shinto for details.> Interestingly, scholar Kyokutei Bakin 曲亭馬琴 (1767-1848) suggests the term “Tanuki” was derived from Ta-no-Ke 田之怪 (rice-field spook) or from Ta-Neko 田猫 (rice-field cat), and says the Japanese sometimes refer to Tanuki as Ya-byō or Ya-myō 野猫 (field cat), and to cats as Ka-ri 家狸 (house tanuki). <see Bakin’s Enseki Zasshi 燕石雑志, Chapter 5, Tanuke 田之怪 section or photo, Waseda University Library> Art historian Katherine M. Ball (1859-1952) says tanuki were known commonly in China as Yě Māo 野猫 (wild cat; cross between foxes and cats), but she provides no reference (p. 141). In Japan’s Osaka-Kyoto-Kobe sake brewing area, the Tanuki is also popularly known as mameda 豆狸 (small tanuki, lit. “bean tanuki”), for he likes to stuff himself on beans (mame 豆) and to steal sake on rainy nights. If we employ Bakin’s rational, we could easily replace the da 狸 of mameda with ta 田 (field), which would yield 豆田, or bean field, again connecting Tanuki with cultivation & food.

Tanuki remain relatively unknown in Japan until the late 16th and early 17th centuries, after which they appear in countless Edo-era stories (see Tanuki Tales from Japan below; also see De Visser). These tricksters can transform into any living or inanimate shape. Real Tanuki live in the lowlands, forests, and mountain valleys, and therefore Tanuki are most often shown playing tricks on hunters and woodsmen. But they also enjoy misleading learned scholars, and therefore shape-shift into Buddhist monks (as do foxes) with a deep knowledge of the sutras. They can cast powerful illusions (like foxes), turn pebbles and leaves into fake money or dung into a delicious-looking dinner, conjure up mirages of entire cities and palaces, appear as one-eyed demons able to produce thunder and rain, rob the bodies of the dead, and cause pebbles to rain from the sky. In some tales, they are even gifted calligraphers. The Tanuki of Japan are also lovers of Japanese sake (rice wine), and in artwork are depicted commonly with a sake flask in one hand and a promissory note in the other (a bill it never pays). These latter attributes are purely Japanese (see Table 2) with no connection to Chinese fox lore. The underlying link to China’s fox, however, has not been forgotten. In the 1994 hit movie Heisei Tanuki, a Tanuki changes into a white fox and scares the wits out of the people who want to move a Shinto shrine to develop the land.

SPECULATION. Why did Tanuki become popular in the Edo Period? From the 13th through 15th centuries, the orthodox Buddhist sects (Shingon and Tendai plus the Six Schools of Nara) competed fiercely for followers, not only among themselves, but against the newly formed and thriving schools of the Kamakura reformation (Pure Land, Zen, and Nichiren) -- the latter stressed pure and simple faith over complicated rites and doctrines and deplored the perfumed embroidery of the court and the intellectual elitism of the entrenched monasteries. Amidst this volatile scene, Japan's orthodox sects probably employed Buddhist deities, local kami, and yōkai 妖怪 (fantastic creatures like the Tanuki) in new formats to attract and maintain their followers. The Seven Lucky Gods of Japan, for example, appeared between the 15th and 17th centuries.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17th Century Tanuki & Mujina Artwork

|

|

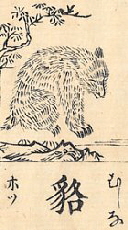

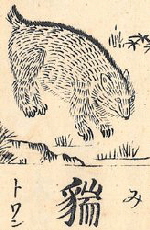

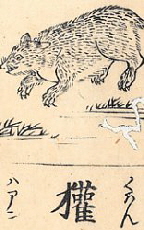

Tanuki artwork did not figure prominently in Japan’s visual culture before the 17th century. As far as I know, the below images are the oldest extant representations of the creature. One comes from the Sansai-zue 三才圖會 (Chn. = Sāncáitúhuì, San Ts'ai T'u Hui, by Wang Qi 王圻), lit. Illustrated Compendium of Heaven, Earth, and Humanity, a Chinese document dated to 1610. Two others come from the Kinmōzui 訓蒙図彙 or 訓蒙圖彙 (Collected Illustrations to Instruct the Unenlightened), a 20-volume Japanese work compiled in 1666 by Nakamura Tekisai 中村惕斎 (1629-1702) and considered Japan's first illustrated encyclopedia. The Kinmōzui went through numerous editions (see digitized 1789 version at the Kyūshū University Museum Digital Archive) and sparked the creation of many other similar works. It drew its inspiration from the earlier Sansai-zue from China. Two points worthy of mention: (1) the Kinmōzui says nothing about Tanuki’s supernatural powers; (2) Tanuki is grouped together with creatures it physically resembles, like the fox, wolf, and badger. <see Michael D. Foster (2008), pp 35-42>

|

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

|

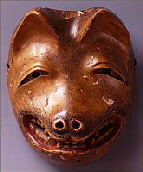

Tanuki Mask

Kyōgenmen 狂言面 (masks for Kyōgen plays). 16-17th century.

See Tanuki Masks below.

PHOTO: Wakayama Museum

|

Tanuki 狸

Chn. = Lí

Fox-like Animal

From 1666 Kinmōzui.

PHOTO: this J-site

|

Mujina 貉 or 狢

Chn. = Hó or Háo

Conflated with Tanuki.

From 1610 Sansai-zue

PHOTO: this J-Site.

|

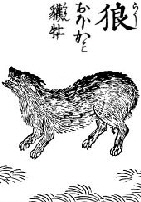

Wolf 狼 or Badger 貛

Wolf C = Láng, J = Rō

Badger C = Huān, J = Kan

Conflated with Tanuki.

PHOTO: 1666 Kinmōzui

|

|

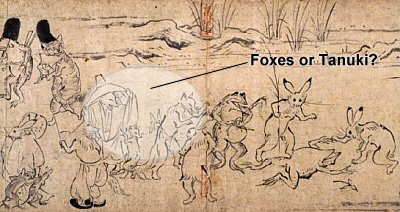

NOTE: Fox-like, Tanuki-like creatures appear in the 12th-century comical and satirical hand scroll known as Frolicking Animals and Humans (Chōjū Jinbutsu Giga 鳥獣人物戯画), a national treasure owned by Kōzan-ji Temple 高山寺 in Kyoto. These creatures are most probably FOXES -- the Tanuki, if we recall, does not make an appearance in written Japanese texts until the 13th century. Similar creatures may appear in 16th-17th century works such as the comical Hyakkiyagyō Emaki 百鬼夜行絵巻, the Bakemono Zukushi 化け物ずくし (Complete Bakemono; artist unknown), and the 1737 Hyakkai Zukan 百怪図巻 (Illustrated Scroll of a Hundred Mysteries) by Sawaki Sūshi 佐脇嵩之 (1707-1772). But I did not have the opportunity to review these documents and therefore they are not discussed herein. If they contain Tanuki artwork, please contact me.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18th Century Tanuki, Mujina, Mami, & Fox Artwork

|

|

The below drawings come from the Wakan Sansai-zue 和漢三才図会, a Japanese encyclopedia completed around 1715 AD. One shows Tanuki standing on his hind legs, but all the others are based largely on the real-world appearance of the animals. Two points are worthy of mention: (1) Like the earlier Kinmōzui, the Wakan Sansai-zue says little about Tanuki’s magical powers, except “like a kitsune (fox), an old tanuki will often transform into a yōkai;” (2) Tanuki is still grouped together with creatures it physically resembles, like the fox, wolf, and badger. <see Foster (2008) for details, pp 35-42> Also, this encyclopedia says eating Tanuki flesh in the form of soup cures piles and running ulcers. <see De Visser, p. 102> Even today, people eat a soup called Tanuki Jiru 狸汁.

|

|

click to enlarge click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge click to enlarge

|

|

Tanuki 狸

Chn. = Lí

Fox-like Animal

Photo Vol. 38

|

Mujina 貉 or 狢

Chn. = Hó or Háo

Fox-like Animal, Nocturnal

Photo Vol. 38

|

Mami 貒 or 猯

Chn. = Tuān

Fox-like, Badger-like

Photo Vol. 38

|

Kan / Ken / Gen 貛

Chn. = Huān

Mami-like BADGER

Photo Vol. 38

|

|

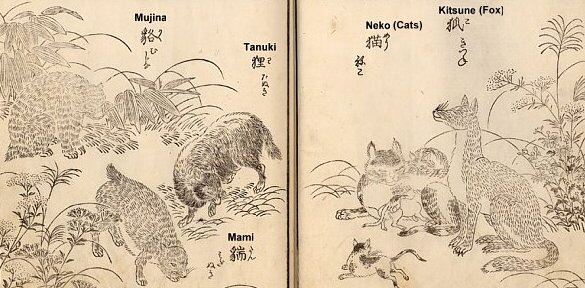

Tanuki 狸 (C = Lí), Mujina 貉 or 狢 (C = Hó, Háo), Mami 貒 (C = Tuān), Kitsune (C = Hú), Cats 猫 or 貓 (C = Māo)

From the 1789 Japanese document Kashiragakizōho Kinmōzui Taisei 頭書増補訓蒙圖彙大成.

These animals appear on adjoining pages -- suggesting perhaps some interrelation, not just similar physical traits.

Photo Source: Kyūshū University Museum Digital Archive.

|

|

NOTE: The Wakan Sansai-zue 和漢三才図会 (Illustrated Japan-China Compendium of Heaven, Earth, and Humanity, aka Collected Japanese-Chinese Illustrations of the Three Realms) is a 105-volume Japanese encyclopedia released around 1715 AD, attributed to Osaka-based medical practitioner Terajima Ryōan 寺島良安, and republished numerous times. This important work has been digitally scanned by various organizations (Kyūshū University Museum Digital Archive, Wakan Entrance || V 38; as well as the National Diet Library, V 1-36 || V 37-71 || V 72-105). The Tanuki image above is a near-exact copy of one appearing in the earlier 1666 Kinmōzui 訓蒙図彙. Both documents were created in the same spirit as the 1610 Chinese work Sansai-zue 三才圖會.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Late 18th Century Tanuki, Mujina, Fox, & Similar Creatures

|

|

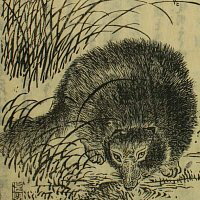

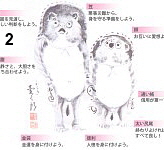

The below drawings come from the Zōho Shoshū Butsuzō-zui 増補諸宗仏像図彙 (1783), the enlarged version of an earlier text (1690) known as the Butsuzō zui 仏像図彙 (Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images). Both are monumental dictionaries of Buddhist iconography and contain hundreds of black-and-white drawings. Here we present eight drawings from a Zodiac grouping known as the Thirty-six Calendar Animals (Sanjūroku Kingyōzō 三十六禽形像; alternatively known as the Chikusan Reiki 畜産暦). The group originated in China, wherein the 36 were divided into four clusters, with each cluster made up of nine animal-deity pairs (4 X 9 = 36). The four clusters represent the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, west). The animals are also grouped in triads -- three animals are combined under one of 12 Zodiac Signs (3 X 12 = 36). In Japan, the group appeared in the Nichū Reki 二中暦, a Japanese calendar from the second half of the 14th century. Curiously, eight of the 36 appear “fox like” -- almost identical in physical attributes. These eight (presented below) include the tanuki, mujna, fox, wolf, jackal, wild cat, and wild male-female dogs. The mujina, fox and rabbit are combined under the zodiacal sign of the rabbit. The tanuki, leopard, and tiger are combined under the zodiacal sign of the tiger. Western scholars have mistranslated tanuki and mujina for decades as “badger” or “racoon-dog.” But in extant artwork like that shown below, the beasts are clearly “fox-like.” It is therefore puzzling why Western scholars call them badgers and racoon dogs. Click below images to enlarge.

|

|

Tanuki (狸), 6th Day, North

|

Fox (Kitsune 狐), 9th Day, North

|

Mujina (狢), 11th Day, East

|

|

Male Cat (Yū  ), 24th Day, South ), 24th Day, South

|

Female Dog (Inu 狗), 30th Day, West

|

Wolf (Ōkami 狼), 31st Day, West

|

|

Jackal (Sai 豺), 32nd Day, West

|

Dog (Tō  ), 33rd Day, West ), 33rd Day, West

|

Eight of the Thirty-six

Calendar Animals

Sanjūroku Kingyōzō

三十六禽形像

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18th Century Tanuki & Mujina Artwork

|

|

|

Mujina door-panel painting.

by Soga Shōhaku 曽我蕭白 (1730-1781), Asada-ji

朝田寺. Photo J-site.

|

|

Below are three drawings by Toriyama Sekien 鳥山石燕 (1712-1788). In his artwork, Sekien depicts the Mujina (not the Tanuki) as the shape shifter, suggesting that the nebulous Mujina is more skilled than the Tanuki. Japan’s Mujina legends do in fact predate Tanuki legends. From the 8th-century Nihongi we learn mujina have the power to change into humans, and also that one carried a mysterious pearl with supernatural power in its stomach (similar to foxes in Chinese/Japanese lore, which possess a round jewel of great power). The mujina thereafter surprisingly disappears from Japanese literature and does not resurface until the 18th century -- by which time it was easily confused/conflated with the popular Tanuki. Both creatures are mischievous shape-shifting fox-like spooks who disguise themselves as monks or hags or Buddhist divinities, haunt houses, and play pranks on unwary humans. Today, however, they are harmless rogues who help and amuse more than annoy. |

|

|

|

|

|

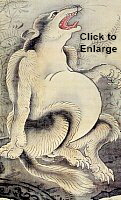

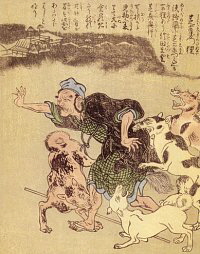

Bake Danuki 化け狸 (lit. = shape-shifter Tanuki) from the 1776 Gazu Hyakkiyakō 画図百鬼夜行 (Illustrated Night Parade of 100 Demons). Tanuki gazing at the moon was a common artistic theme in Japan’s Edo era.

PHOTO: J-site 1 || 2 || 3

|

Mujina 貉 momentarily assumes its animal form while making tea; from 1781 Konjaku Gazuzoku Hyakki 今昔画図続百鬼 (Continued Illustrations of Many Demons Past and Present). The tea-kettle theme is related to the Bunbuku Chagama tale.

PHOTO: J-site 1 || 2

|

Fukuro Mujina 袋貉 (lit. "bag mujina") from the 1784 Hyakki Tsurezure Bukuro 百器徒然袋 (Idle Collection Bag of Many Things). Fukuro means both "bag" and "bag of tricks." Here a female-like Mujina wears sack-like clothes & carries a heavy bag over its shoulder. PHOTO: J-site 1 || 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

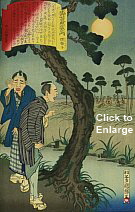

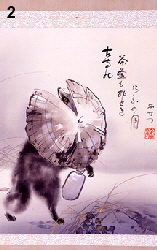

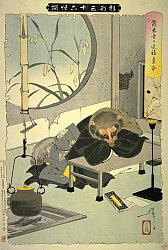

18th, 19th, 20th Centuries - Tanuki Under the Moon

|

|

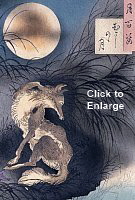

The moon is a common theme in Japanese Tanuki lore and artwork, for it is on moonlit nights that the creature performs its beguiling belly drumming and mischievous shape-shifting. In the popular tale Kachi Kachi Yama, Tanuki is traveling to the moon in a mud boat when it is killed. Japan’s Tanuki derives from China’s old fox lore, and in China, the fox is considered nocturnal. In old Chinese and Japanese texts, the howling of a fox or tanuki under the moon was considered largely a bad omen, but in some cases it could portend good luck. <See, for instance, the 14th century Nichū Reki 二中暦, a Japanese zodiac calendar. It describes the bad and good omens portended by the howling of foxes and tanuki. Also see De Visser, p. 13.> In Europe, too, tales of the werewolf (a fox-like creature) are common and linked to evil acts performed on moonlit nights, including tales from Hungary, Romania, Albania, and elsewhere.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tanuki Howling at Moon.

By Soga Shōhaku 曽我蕭白 (1730 - 1781).

H = 124 cm, W = 15 cm.

Photo this J-Site

|

Tanuki & Moon 月小狸.

By Katsushika Hokusai

葛飾北斎 (1760 to 1849).

Photo this J-Site

|

Tanuki & Moon by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka 月岡芳年 1839-1892. From 100 Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki Hyakushi 月百姿).

Photo this J-Site

|

Tanuki & Moon

By Suisen Inoue Shūjō

水仙井上秀城 (b. 1941).

Available for online

purchase at this E-Site

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Edo Period Tanuki Masks -- Kyōgenmen 狂言面

|

|

Kyōgenmen 狂言面 are masks used for Kyōgen 狂言 plays. Kyōgen is a comic theater form, often performed between acts of the more serious Nō 能 theater, and known as Sarugaku 猿楽 during the Muromachi era (15th-16th centuries). Other animals commonly appearing in Kyōgen plays are the fox and monkey. The Kyōgen play known as Tanuki no Hara Tsuzumi 狸の腹鼓 (Tanuki's Belly Drum) is very recent, written in 1842. In it, Tanuki is female and disguises itself as a nun. She chants an account of the horrors of hell befalling those who kill the animal, and thereby convinces the hunter to stop pursuing the beast. Later, however, the hunter discovers her true identity and begins the hunt once more.

|

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

|

Tanuki Mask

A Kyōgenmen 狂言面,

or mask used for comical Kyōgen plays. Dated between the 15th-17th centuries. Photo from

Wakayama Museum

|

Tanuki Mask

Used in Kyōgen scene

when hunting Tanuki, hence

named I-Tanuki 射狸,

lit. “Shot-Upon Tanuki.”

Photo Information-Technology Promotion Agency of Japan

|

Tanuki Mask

For Kyōgen play Tanuki no

Hara Tsuzumi 狸の腹鼓

(Tanuki's Belly Drum)

Dated to 19th Century.

Photo from the

Tokugawa Art Museum

|

Fox Mask

Other animals appearing in

Kyōgen plays include the fox

and monkey. Presented here

for comparative purposes.

Photo Information-Technology Promotion Agency of Japan

|

|

|

Photo at left. Bronze ding (cauldron) tripod with bear-shaped legs. Western Han China, 2nd century BCE. H = 18.1 cm, diameter = 20 cm. Excavated in 1968, from tomb 1, Han tombs at Mancheng, Hebei Provice. Hebei Provincial Museum. Photo from exhibition catalog (p. 147) entitled Treasures of Ancient China, Oct. 24 - Dec. 17, 2000, Tokyo Nat’l Museum, Published by Asahi Shimbun. The catalog notes the “bear-shaped legs.” But in many ways, this looks like a Tanuki -- as can be seen by viewing the many photos on this site page. Nonetheless, Tanuki lore and artwork are essentially non-existent in China..

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Edo Period Tanuki Netsuke 根付

|

|

Netsuke 根付. Ne 根 means "root" while tsuke 付 means "attach." Netsuke are miniature sculptures that appeared around the 17th century. They were attached to one's belt to hold a larger container (inrō 印籠) which carried tobacco, medical powders, etc. Says JAANUS: “A netsuke and inrō were connected by a double cord with a sliding bead (ojime 緒締) which tightened the cord and held the tiered sections of the inrō together. The netsuke, fastened on one end of the cord, was then slipped under a man's narrow belt (obi 帯), allowing the inrō or other small articles (a tobacco pouch, for instance) to hang freely at his side. Travelers used these small cases to carry pills, medicinal powders, and other personal items.” Read full entry at JAANUS. To learn more, see the Meinertzhagen Card Index on Netsuke in the Archives of the British Museum (two-volume facsimile version still available on used-book market), the International Netsuke Society and the article by Kendall Brown in its 1997 journal entitled “Why Art Historians Don't Study Netsuke and Why they Should,” and the illustrated version of The Hare with Amber Eyes (2011) by Edmund de Waal. For a review of the latter, please click here.

|

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

|

Tanuki as tea kettle.

Wood. Signed Sosui. Photo from International Netsuke Society.

See Lucky Tea Kettle story below.

For photo source, see here.

|

Tanuki with sake flask, wearing lotus-leaf hat. Wood. Signed Tomokazu. Photo International Netsuke Society. <Source>

|

Tanuki. Ivory. Late 18th century, Kyoto School. Wears lotus-leaf hat, carries gourd & drum. Photo from Christie’s.

|

Tanuki shifting into monk. Ivory. Kyoto School. Photo from International Netsuke Society. <Source> See Tanuki dressed as monk.

|

|

NOTE: The above netsuke are tentatively dated between the mid-18th and mid-19th centuries.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19th Century - Tanuki’s Big Belly and Belly Drum

Belly Drum Tanuki, Hara Tsuzumi Tanuki 腹鼓狸 or Tanuki no Hara Tsuzumi 狸腹鼓

|

|

The origin of Tanuki’s big paunch and belly-drumming magic is unclear (to me), but various 18th-century Japanese texts mention these attributes and extant 19th artwork portrays it. For possible origins, see below. In the 1742 Japanese text Rō-ō Chawa 老媼茶話 (Tea Talk from Old Women), we read of an old tanuki who was saved by a child. The tanuki then requested to live under the veranda of the child’s home. The request was granted, and the tanuki was thereafter fed daily by the child’s father, and in return the creature entertained the household nightly by playing his belly drum. In the 18th-century Shōnai Kasei Dan 庄内可成談, we read about belly-drumming music on clear autumn nights. In many legends, the tanuki’s drumming is meant to beguile travelers and lead them astray, but we must also note that in popular belief, the Tanuki get together now and then just for fun, to make merry and dance in abandoned shrines or fields under the moonlight. Art historian Katherine M. Ball (1859-1952) says only tanuki who have reached 1000 years in age can play the belly drum (p. 141), although she fails to give any reference. Tanuki’s belly drumming may have been known centuries earlier, for a poem by Jakuren 寂蓮 (aka Fujiwara no Sadanaga 藤原定長, death 1202) goes: “An old monastery, where nobody lives, where even the bells give never a sound, and tanuki alone beat the temple drum.” <De Visser, pp. 71-72, 102, 156>

|

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

|

Tanuki howling while beating a mokugyo 木魚 (wooden fish gong). By Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (1831-1889), c. 1881. Spoof on Buddhist monks who regularly use mokugyo during recitations of mantra & sutra. Photo J-site

|

Netsuke in the form of a

Tanuki drumming on its belly; attached to container with Kotobuki 壽 (long life) etched on its cap. Japanese, Late 19th century. MFA Collection (Boston). Explore all Tanuki artwork at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

|

Tsuba 鐔 (sword guard) with design of a Tanuki drumming on its belly beneath the moon. Japanese, Mid-19th C, by Takahashi Yoshitsugu (1842–1873) of the Tanaka School of artists. MFA Collection (Boston).

|

Tanuki (as retailers) celebrate the first sale of the new year by beating on a large “scrotum” drum. By Utagawa Kuniyoshi 歌川国芳 (1798-1861). Photo KuniyoshiProject.com. See below for details on Tanuki’s large scrotum.

|

|

Tanuki Bayashi 狸囃子. “An example of uncanny sounds,” says scholar Gregory Smits, “would be Tanuki Bayashi 狸囃子 (literally ’tanuki accompaniment’). In this case, in the dead of night, a lone person suddenly hears the sound of festival drums. But the drums sound a little odd, and the sound seems to have come out of nowhere and its direction is hard to pinpoint. Surprised, the hearer tries to get a fix on the sound, but it fades away. There is no festival or any other occasion for drumming anywhere nearby. What is going on? According to Japanese lore, the drumming is that of an animal trickster known as a tanuki. Indeed, children in Japan today are likely to be able to sing a one-verse song ditty that goes: Tan, tan, tanuki no kintama wa; kaze ni fukarete bura bura (features onomatopoeia, but, roughly: The tanuki's balls are blown back and forth by the wind). Anyway, the eerie sound of mysterious drumming at night was thought to be the result of one or more tanuki drumming on their bellies or (ouch) scrotums.” <end quote>

In some stories, the Tanuki is so enraptured by musical excitement that he beats (drums) his belly bare and dies, or enlarges his tummy to such great girth that he bursts. See, for example, the 1875 story from the Edo Tōkyō Kaii Hyaku Monogatari. PHOTO: Honjo Nanafushigi no Uchi 本所七不思議之内 (Seven Wonders of Honjo), by Utagawa Kuniteru 歌川国輝 (fl. 1830-1850), Waseda Univ.

|

Tanuki Bayashi 狸囃子

Group of Tanuki beat their bellys under the moon.

See artwork citation

in adjacent column.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ORIGINS OF BIG BELLY & BELLY DRUMMING

|

|

|

Tanuki Te-aburi 狸手焙り by Ōtagaki Rengetsu 大田垣蓮月 (1791-1875). A te-aburi is a hand warmer or heat radiator. Ōtagaki was a Buddhist nun and skilled poet, potter, painter and calligrapher. Photo Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park or SCCP

Pudgy Tanuki, Ceramic

Early Shōwa era, c. 1920s.

By Imai Ri-an 今井狸庵, Kyoto, Kiyomizu. Photo from Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park or SCCP

Tanuki Incense Burner, Shigaraki

信楽狸香合, by potter

Tani Toshitaka 谷敏隆 (b. 1943). Photo from Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park or SCCP

|

|

In extant Japanese artwork, Tanuki’s big belly and tummy-drumming magic clearly predate Tanuki’s large scrotum and nut-bag thumping. Yet the origin of Tanuki’s large abdomen and unusual musical talents remain shrouded in the mists of uncertainty. Thankfully there is ample circumstantial evidence to allow us to make “educated guesses” -- to conjure up explanations that sound very plausible. Below are some of mine. Any one of them may be the origin of the other, or they may all have developed in tandem and interactively, but it is impossible to say.

- OBSERVATION. The magical animals of Chinese and Japanese mythology are commonly depicted with personalities, which are based on a combination of fact, observation, and folklore. The real Tanuki is a stout beast who “stuffs itself with fruit and berries in the fall and spends the winter in communal dens in a period of lethargy and quasi hibernation.” (David Macdonald, Oxford, 1992, pp. 83 & 173). This helps to explain Tanuki’s inflated belly.

- LINGUISTIC (WORD PLAY). Stuffing oneself and then sleeping it off implies a life of ease, comfort, and contentment. It also implies a pot belly. The Japanese term KOFUKU 鼓腹 (鼓 = drum, 腹 = stomach) means just this -- to live a life free of care, to eat until one is full, to suffer no dissatisfaction, no discomfort. In common usage, KOFUKU means “to pat one’s belly” as a sign of satisfaction. But wait !! Reverse the characters and it becomes HARA TSUZUMI 腹鼓, literally “belly drum.” Incidentally, the pot-bellied Buddhist divinity Hotei (one of Japan’s Seven Lucky Deities) is known as the God of Contentment & Happiness. It is no stretch of the imagination to say that a well-fed carefree life brings plumpness and girth, which throughout most of Asia signifies the good life, the happy life, the lucky life. The pudgy Tanuki statues one sees everywhere in modern Japan thus signify prosperity and wealth.

- SOCIAL SATIRE. Tanuki appear often in artwork in the disguise of a fat well-nourished Buddhist monk sitting on a cushion. Tanuki are also occasionally represented beating a wooden drum called the mokugyo 木魚 (fish gong), as in the drawing by Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831-1889) shown above. Buddhist monks (then & today) regularly use mokugyo during their recitations of mantra and sutra. “These representations of Tanuku,” says scholar U.A. Casal (pp. 56-57), “are not exactly a compliment to that fraternity. But Buddhist priests, the same as the Catholic ones in Europe, were at times and by certain groups considered no better than charlatans ensnaring the credulous, especially the women. They were thus deemed to be rather dangerous fellows destroying in the end those whom they pretend to save. The Tanuki Bōzu 狸坊主 (monk) is the sly but ruthless individual to whom any pretext and deception, even an apparent piousness, will serve his ends.”

- MUSIC. Tsuzumi or Tsutsumi 鼓 is a drum, thought to have originated in China or Korea. Shaped like an hour-glass, and played with the hands, it is used frequently in traditional Japanese music and Noh theater. The belly-drumming Tanuki is known as Hara Tsuzumi Tanuki 腹鼓狸. The sound produced by Tanuki’s belly drum in traditional times was said to be dokodon dokodon dokodon, or simply don don don. In modern times, the sound is given as ponpoko pon pon ポンポコ、ポン、ポン, which the Tanuki is also said to “sing.” The fox, when happy, cries kon kon. In the real world of Japanese music, Tsuzumi produce the main upstroke sound “don.” <see Ashgate Research Companion to Japanese Music, pp. 138-139; also hear digital sound sample at this E-site>. Additionally, Casal (pp. 56) says “I wonder whether this ’drumming’ idea is not a faint memory of the message-drums of south-sea islanders -- a strong influx into Japan certainly came from that quarter.”

Shikitei Sanba (Samba) 式亭三馬 (1776-1822), a well-known writer of Kokkeibon 滑稽本 (humorous books), wrote a piece entitled Hara Tsuzumi Tanuki Tadanobu 腹鼓狸忠信 (True Stories of the Belly-Drumming Tanuki) -- see his work at the University of Tokyo Digital Archives. Shikitei is more widely known for his Ukiyoburo 浮世風呂 (The World at the Bath-House; 1809-13) and Ukiyodoko 浮世床 (The World at the Barber Shop; 1813-14).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19th Century - Tanuki’s Giant Scrotum (Nut Sack)

|

A curious and defining characteristic of Tanuki is its gigantic scrotum (not testicles). In Japanese slang, these are known as Kinbukuro 金袋, or “money bags.” Tanuki’s large scrotum does not mean over-indulgence in sex, but rather “luck with money.” The most accepted explanation for his king-size nut sack comes from Ōwaku Shigeo 大和久重雄 in his book Hagane no Chishiki 鋼の知識 (Knowledge about Steel; Diamond Shakan, 1971). Writes Alice Gordenker in the 15 July 2008 Japan Times: “Ōwaku traces the super-size scrotum story to metal workers in Kanazawa Prefecture. To make gold leaf, these craftsmen would wrap gold in a tanuki skin before carefully hammering the gold into thin sheets. It was said that gold is so malleable, and tanuki skin so strong, that even a small piece [of gold] could be thinned to the size of eight tatami mats (Hachijōjiki 八畳敷き; about 12 sq. meters). And because the Japanese for ’small ball of gold’ (kin no tama 金の玉) is very close to the slang term for testicles (kintama 金玉), the eight-mat brag got stuck on tanuki's bag. Soon, [scrotum] images of a tanuki began to be sold as prosperity charms, purported to stretch one's money and bring good fortune.” <end quote> In the same story, Gordenker discusses popular school-yard songs celebrating the Tanuki’s large sack. “Tan-tan-tanuki no kintama wa, kaze mo nai no ni, bura bura.” (translation = Tanuki's balls, there isn't any wind but they still go swing, swing, swing). <end quote Gordenker>

In many Tanuki legends, the scrotum is stretched to the size of eight tatami mats. Yet others point to the word Senjōjiki 千畳敷き (1,000 tatami mats) as an indication of Tanuki’s scrotum-inflation magic. In Japan, the scrotum and testes are symbols of good luck rather than overt sexual symbols. In the Japanese movie Heisei Tanuki Gassen Ponpoko, the Tanuki stretches out its scrotum and uses it as a parachute in a desperate suicide attack against the money-grubbing humans. The 18th & 19th centuries were apparently a heyday for low humor. See Robin D. Gill’s Octopussy, Dry Kidney & Blue Spots - Dirty Themes from 18th -19th Century Japanese Poems, Paraverse Press 2007, starting page 177 and including the section on Senki-mochi 疝気持 or Lumbago. Gill writes that Tanuki’s “scrotal skin was used to pound out gold-leaf [by metal workers], someone got confused about what stretched, and graphic artists had so much fun finding uses for enormous balls that the mistake stuck for centuries.” <p. 183> Today, Tanuki’s large scrotum represents “luck with money” and “expanding wealth” -- it is in no way connected to sexual indulgences, as most web sites so falsely convey. |

|

19th Century - Tanuki’s Scrotum Slideshow (34 photos)

|

|

In the 19th century, various Japanese artists created numerous (and humorous) woodblock prints showing the Tanuki's large scrota, nut sack, kinbukuro 金袋 (money bags, gold bags), or kintama 金玉 (golden balls) in creative ways. Such artists included the famed Utagawa Kuniyoshi 歌川国芳 (1798-1861), Tsukioya Yoshitoshi 月岡芳年 (1839-1892), and Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (1831-1889).

Click above image to jump to slideshow

|

|

|

21st Century - Tanuki’s Scrotum on Commerical TV

|

|

Click above image to view ad

by Japanese construction firm

Anabuki Kōmuten 穴吹工務店.

Snippet of commercial from

former student at UAT.

See this E-site.

|

This ad from a Japanese construction firm, released sometime around 2005 / 2006, involves Tanuki and Little Red Riding Hood (Anabuki-kin-chan). It portrays Tanuki as one of Little Red Riding Hood’s many forest friends, one whose large nut sack represents “magnifying” one’s dreams and hopes (playing upon the traditional “expanding money bag” symbolism of Tanuki’s giant scrotum). The ad’s message -- join us & you too can have a huge wonderful home. Below translation from this E-site.

- Announcer: The new campaign girl for Anabuki Kōmuten (Anabuki Builders) is the girl you know so well...Anabu-kin-chan! (Little Red Riding Hood!). What's this? All the animals of the forest are here too! All together, let's read with spirit.

- Chorus of girls' voices: Anabu-kin-chan!

- Anabu-kin-chan: Hai (Yes, I’m here & ready!). Then she sings:

It makes your dreams expand, Saabasu Mansion

It makes your hopes expand, Saabasu Mansion

It also makes your breasts expand, expand, expand.

- Suddenly, a Tanuki with enormous nut bags appears.

- Anabu-kin-chan: Wow! ********

- Anabu-kin-chan: Saabasu Mansion

- Commericial Announcer: Anabuki Kōmuten (Anabuki Builders)

Note: Saabasu Mansion is name of real estate they hope to sell.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19th Century - Other Artwork

|

|

The new shōgun, Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (+1542-1616), gains complete hegemony in Japan with his victory over the Toyotomi 豊臣 family in +1615, and thereafter Japan enjoys over 250 years of peace and prosperity under the leadership of 15 generations of Tokugawa shōguns 将軍 (military rulers). The military capital was established in Edo 江戸 (modern-day Tokyo), and secular arts of all kinds flourished among the growing merchant classes, military clans, and the wealthy. Since then, the importance of secular art has forever surpassed that of religious art. Ieyasu, by the way, was irreverently nicknamed Furu Tanuki 古狸 (Old Tanuki), for he was considered a very clever schemer. Additionally, the symbol for eight (hachi 八) appears often inside a circle on Tanuki’s sake bottle. This symbol ㊇ was the old crest (mon 紋) of the Tokugawa family in Owari (present-day Aichi prefecture) and represented the eight districts they once controlled. See What About Hachi below.

|

|

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

|

Tanuki Beating Belly Drum

Ceramic, Late Edo Period

by Miwa Kiraku Vl

三輪喜楽 (6代)

Miwa Kiraku the 6th is was one of the most prolific potters of okimono (realistic figurines); his motifs include the shishi lion & Tanuki.

Photo Asahi Article

|

Takeda Defeats Tanuki,

by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

月岡芳年 (1839 - 1892) from

New Forms of 36 Apparitions (新形三十六怪撰 or Shinken Sanjyuroku Kaisen).

Photo this J-Site.

** See note below **

|

Tanuki Using Giant Scrotums in Funny Ways, by Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (1831-1889). Circa 1864. In top frame, lion dance (Shishimai 獅子舞) and parade. In bottom frame, the Pounding of Rice Cakes (Mochi Tsuki 餅つき). A spoof on Japan’s popular festivals. Photo this J-site.

|

Tanuki atop fox

along with frogs and owl.

Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (1831-1889). Spoof of a 12th-century hand scroll known as Frolicking Animals & Humans or Chōjū Jinbutsu Giga 鳥獣人物戯画. Photo this J-site.

「梟と狸の行列」

鳥獣戯画画稿

|

|

NOTE: In the second photo above (Takeda Defeats Tanuki) and also in the additional photo shown at right, we should perhaps add that Takeda Shingen 武田信玄 (1521-1573) was a powerful daimyō and military leader in feudal Japan. In these paintings, Tanuki assumes the form of a saddle-horse and asks the young Takeda a strategic question. Takeda is angered and uses his sword to strike the saddle, killing the Tanuki (who then returns to his true form). Entitled 田勝千代月夜に老狸を撃の図. Photo at Right. Takeda Defeats Tanuki. By Tsukioka Yoshitoshi 月岡芳年 (1839- 1892). Photo this J-site |

|

Tanuki and Cat. By Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (1831-1889).

A spoof of a 12th-century hand scroll known as Frolicking Animals & Humans (Chōjū Jinbutsu Giga 鳥獣人物戯画). The latter work is a national treasure at Kōzan-ji Temple 高山寺 (Kyoto). Above photo this J-site. See also this J-site and this E-site. Nonetheless, this looks like a Tanuki and White Fox. A wild dog snarls at the white fox (his natural enemy). Plus, by this time, Inari, Dakini, Benzaiten, and Izuna Tengu all ride white foxes, and fox statuary in Japan is often adorned with a red scarf, hat, or bib (a talisman against disease).

|

Tanuki and other frolicking animals, c. 1879

by Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (1831-1889).

杭に繋がれた猿と兎、狸. Photo this J-site.

A 19th-century spoof of a 12th-century hand

scroll known as Frolicking Animals & Humans

or Chōjū Jinbutsu Giga 鳥獣人物戯画.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Meiji Era (1868-1912)

|

|

By the late 19th century, the individual components of Tanuki lore begin to coalesce in artwork. In the decades that follow, these components (big belly or wide girth, sake flask, promissory note, straw hat, giant scrotum, large round eyes, goofy facial expression) become the standard attributes of Tanuki statues -- with the main iconic type we know today established by at least the Taishō Era (1912-1926).

|

|

1. Ceramic Tanuki Dressed as Monk. Meiji Era. H = 12 inches. Photo from jcollector.com

2. Wood Tanuki Procuring Sake. Meiji Era. H = 16 inches. Wood. Photo from jcollector.com

3. Ceramic Tanuki as Monk, with Ikebana Flower Vase. Meiji Era. H = 7 inches. Photo from jcollector.com

View all Tanuki pieces offered by jcollector.com

|

|

|

|

Tanuki Dressed as a Monk (19th & 20th Centuries)

|

|

Tanuki as a Monk (Bōzu Tanuki 坊主狸 or Tanuki Bōzu 狸坊主). A common theme in Tanuki lore and artwork, wherein Tanuki disguises himself as a fat well-nourished Buddhist monk (see discussion of iconography under Big Belly). The tanuki, mujina, and fox appear often as trickster priests in Edo-era Japanese tales. For instance, in the Japanese text Shinchomonshū Ryakki 新著聞集畧記 (circa 1700), we learn about an old spook monk who lived nearly 200 years at a certain monastery. Over that time he saved many gold pieces from donations. But when he was killed by a dog, his true mujina form was revealed. The abbot gave the gold to two laborers who had discovered the dead mujina, but the money was cursed, causing madness and death to the family of one of the two laborers. The other erected a stone monument for the dead monk and held a funeral service. <see De Visser pp 77-79>

|

|

- Ceramic Tanuki dressed as chief bonze (monk), entitled Oshō Tanuki 和尚狸, Meiji Era, by Nin-ami Dōhachi 仁阿弥道八 (1783-1855). Located at the Tokyo National Museum (TNM). Photo TNM. Click image to enlarge.

- Ceramic Tanuki dressed as a plump monk, Rakuyaki Tanuki Te-aburi 楽焼狸手焙, by Ishiguro Munemaru 石黒宗麿 (1893-1968), H = 25 cm, Late Taishō era. Rakuyaki is low-fired ceramic ware. Photo Asahi article.

- Stone Tanuki at Zuisenji Temple 瑞泉寺 in Kamakura. Late Taishō / Early Shōwa (guesstimate). This statue looks like a fox, but the enormous girth of the statue, plus the slightly bewildered expression on its face, helps to identify it as a Tanuki. Photo by Schumacher

- Ceramic Tanuki dressed as a monk, holding begging bowl and rosary. Modern. Located in front of the Taishidō 太子堂 (hall dedicated to Shōtoku Taishi) at Kanjizai-ji Temple 観自在寺, Shikoku. Photo from now-defunct J-website.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Meiji Era (1868-1912) Tanuki Artwork

|

|

In the late 19th century, as Japan races to modernize and catch up with the West, the Tanuki is used as an “educational vehicle” -- as an example of backward thinking that needs to be overcome.

|

|

click to enlarge

Bunbukusha's Trickster Tanuki Assumes 9 Different Guises.

Bunbukusha-chū no Tanuki-oyaji Kyūbake Yarō

文福舎中の狸親父九化野郎

By Hasegawa Sadanobu 二代 長谷川貞信 (1848-1940). The tanuki is a familiar character of folklore known for outwitting human beings by changing into various forms. This trickster creature of popular superstition, according to this story, has finally been captured by the junsa, a policeman symbolic of "enlightened" (modernized) society after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. The truth of the story aside, the "enlightening" tone of the passage toward the end of the article gives a glimpse of the popular psyche of those days. Appeared originally in the Nichinichi Shinbun 日々新聞, Meiji era. Photo and Text from Waseda University Library.

|

click to enlarge

Gambler thoroughly deceived by

a Tanuki disguised as a woman

まんまと狸にだまされた相場師

By Hasegawa Sadanobu

二代 長谷川貞信 (1848-1940)

The title is akin to "a rogue being swindled by a rogue."

Japanese text by Taisuido Risho 大水堂狸昇.

Appeared originally in the

Nichinichi Shinbun 日々新聞

Meiji era

Photo from Waseda University Library.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Taishō Era (1912-1926)

|

|

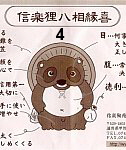

The prototype of today’s pudgy ceramic Tanuki statue emerged in the early 20th century. This iconic type depicts him wearing a straw hat, holding a sake flask in one hand, a promissory note in the other, and sporting a giant scrotum, big belly, large round eyes, and a somewhat goofy facial expression. It is commonly known by the name Sake Kai Tanuki 酒買狸 (literally Tanuki Procuring Sake) and draws its inspiration from an old children's song (16th-17th century) in the Osaka and Kyoto sake-brewing areas (details here). The four images below come from a Tanuki exhibit held by the Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park (SCCP) from March 17 to June 3, 2007. See SCCP and Yakimono Guide (Asahi.com).

|

|

- Sake Kai Tanuki 酒買狸 (Tanuki procuring sake), Shigaraki Okimono, by Fujiwara Tetsuzō 藤原銕造 (1876-1966). Fujiwara Tetsuzō is commonly considered the father of Tanuki ware made in Shigaraki, which has since become Japan’s preeminent location for mass-produced ceramic Tanuki statues. Photo SCCP.

- Sake Kai Tanuki 酒買狸 (Tanuki procuring sake), Shigaraki Okimono, by Fujiwara Otoshiro 藤原乙次郎, H = 122 cm. Late Taishō Period. Photo Asahi Story.

- Sake Kai Tanuki 酒買狸 (Tanuki procuring sake), Okimono, by Matsushita Fukuichi 松下福一, Late Taishō / Early Shōwa, Tokoname Folk Crafts Research Center 常滑市民俗資料館蔵 in Aichi Prefecture. Photo Asahi Story.

- Sake Kai Tanuki 酒買狸 (Tanuki procuring sake). Early Shōwa era, c. 1920s. H. = 30.4 cm. By Imai Ri-an 今井狸庵, Kyoto, Kiyomizu. Photo SCCP and Asahi Story.

Three Glazed Ceramic Tanuki -- from www.jcollector.com

Taishō Era (1912-1926). Two statues wear a straw hat and hold a sake bottle and promissory note.

One statue holds a leaf, which it puts on its head prior to shape-shifting. JCollector says: “Tanuki

was adopted as a symbol of aristocratic excess during the Edo period. Often displayed in front of

sake houses to hint at the entertainment offered therein.” <end quote>

|

|

|

|

|

20th and 21st Centuries (Contemporary Japan)

|

|

Today Tanuki is an extremely popular icon of generosity, cheer, and prosperity -- he has lost all his evil and frightening attributes and become instead a cute icon of wealth and luck. Pudgy ceramic statues of Tanuki are found everywhere, especially outside bars and restaurants, where a goofy Tanuki effigy typically beckons drinkers and diners to enter and spend generously. Since Tanuki’s large scrotum symbolizes “expanding weath” and “luck with money,” Tanuki is also considered a wealth-bringing icon, one that adorns residential gardens and public spaces. As a bringer of wealth, he has been appropriated by Japan’s commercial interests, and appears in key chains, cell-phone straps, bakery goods, comic books, cartoons, movies, and all endeavors bent on making money.

|

|

1. Modern Ceramic Tanuki, Private Garden, Kamakura, Japan.

2. Modern Ceramic Tanuki w/child. Private Garden, Kamakura.

This is a very interesting statue, suggesting the themes of fertility and parenthood. But if you look closely,

Tanuki seems to be both male and female, as per the large breasts and the large nut sack. In fact, many

modern male Tanuki statues are depicted with big breasts. Perhaps this is “meant” to symbolize both

male-female qualities. Or perhaps I am overthinking the issue. Just a curious aside.

Modern Tanuki statues with male member still intact !!!

It is still generally uncommon to find statues of Tanuki with the “male member” still intact.

1. Stone statue outside shop in Kamakura City. Photo by Mark Schumacher.

2. Wood statue near Mt. Unzen 雲仙岳, Nagasaki Pref. (Kyūshū). Photo by Baron Knoxburry.

|

Donald Richie, in his review of Nicholas Bornoff’s book Things Japanese, has this to say: “The Tanuki makes an appearance, holding an empty sake bottle in one paw, an account book in the other -- signifying that this money was wasted on wine and women. As Bornoff tells us: ‘Some say that the vast scrotum is due to sexual overindulgences but, since his penis has disappeared, another interpretation is more likely’ -- an entertaining aside from Bornoff, the author of Pink Samurai: An Erotic Exploration of Japanese Society.” <end quote> EDITOR’S NOTE. Richie is wrong about one thing -- Takuni’s sake flask and promissory note do not signify “money wasted on wine and women.” As discussed earlier in this report, Tanuki’s large scrotum represents “expanding wealth” and “lucky with money.” The promissory note derives from Tanuki’s ability to pay “seemingly real” money for his merriment, but after he departs, the unlucky seller discovers that the money is nothing more than worthless pebbles, dirt, and leaves.

|

|

1. Tanuki as two Buddhist guardian deities called the Niō. Photo from this J-site.

2. Tanuki as woman with tea & cookies. By Hirotsune Tashima 田島弘庸 (b. 1969). Photo SCCP (J-site)

1.Cute sake-drinking Tanuki. Kazuyuki Kurashima 倉島一幸 (b. 1970) Character Designer & Illustrator.

2. Kisaemon Tanuki. Brand character for a Shikoku-made manjū 饅頭 (a sweet bun). Photo from this J-site.

3. Tanuki-shaped sweets. Photo from this J-site.

Tanuki statues at the Ikaho Onsen 伊香保温泉 in Shibukawa City 渋川市, Gunma. Photos this J-site.

- Nonbei Tanuki のんべえ狸 (Boozehound Tanuki), drinking sake with a sake cup (guinomi) as a hat.

- Gomasuri Tanuki ゴマスリ狸 (Brown-Noser Tanuki); gomasuri (lit. = grind sesame seeds) is slang for sycophantic behavior. Here we see Tanuki grinding sesame seeds using a bowl and pestle.

- Gariben Tanuki ガリ勉狸 (Eager-Beaver Tanuki). Gariben means to cram, to pound the books.

- Zenigeba Tanuki 銭ゲバ狸 (Money-Power Tanuki). Holding gold coins; symbol for money ㊎ written on his ledger.

- Chōshu Tanuki 長寿 (Long-Life Tanuki). Stands outside onsen entrance; wash basin atop its head.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TANUKI ATTRIBUTES (Traditional)

|

|

What About Leaf on Tanuki’s Head?

the Umbrella? the Straw Hat?

The shape-shifting Tanuki is said to put leaves on its heads and to chant prior to transformation -- just as the fox must balance a human scull and bones atop its head before shape shifting. In some legends, the leaf is the sacred lotus plant of Buddhism. It is also believed that Tanuki can change leaves into money (as one of them did in the 1994 hit movie Heisei Tanuki Gassen Ponpoko). In the computer game "Super Mario Brothers," when Mario gets a leaf, he gains pointy ears and the tail of a Tanuki.

Since Japan’s Tanuki is derived from old Chinese fox lore, we must look to China for clues. In the Sōshinki 搜神記 (Chn. = Sōushénjì, Sheu Shen Ki), a 4th-century Chinese text attributed to Gan Bao 干寶 (fl. 317-322), we learn that a devout monk “who passed the night as a grave corpse, saw in the moonlight a wild fox placing withered bones and a skull upon its head, and when the animal after some practice succeeded in moving its head without dropping them, it covered its body with grass and leaves and changed into a beautiful woman.“ <quoted from De Visser, p. 4> In the 8th-century Chinese text Yūyōzasso 酉陽雑俎 (Chn. = Yū Yáng Zá Zǔ, Yu Yang Tsa Tsu), “when the fox desires to appear as a spook, he puts a human skull on his head and salutes the Great Bear constellation.” <quoted from De Visser, p. 5>

Tanuki’s umbrella and straw hat are recent additions. Both appear in Tanuki artwork around the late 19th century (see below photos). Although exact origins are unclear, the “umbrella or straw hat” motif most probably sprang from a popular old song (16th-17th century) in the Osaka and Kyoto sake-brewing areas; one stanza of the song describes a small tanuki (mameda 豆狸) who steals sake on nights of non-stop drizzling rain (details here). Artists no doubt played upon this association with rain and sake, and began depicting Tanuki journeying to the brewery with sake flask and umbrella (or straw hat). In extant artwork, the umbrella predates the straw hat. In contemporary times, however, the straw hat has supplanted both the leaf and the umbrella. Most of the old folklore has disappeared as well. Today, the makers of Tanuki statues say the straw hat symbolizes the virtue of “readiness” -- be prepared for bad weather or bad luck. See Eight Virtues of Tanuki below.

|

|

- Tanuki Okimono 置物 (decorative carving), Meiji Era, artist unknown. This piece shows Tanuki holding an umbrella and carrying a sake flask. Photo from odanuki.com (now-defunct J-website).

- Tanuki Procuring Sake, holding umbrella and sake flask, by Nakamura Fusetsu 中村不折 (1866-1943), Photo from SCCP. I’m not quite sure about the origin of this piece.....it may possibly come from Inezuka Hōdō 稲塚鳳堂画 (Showa-era artist). See photo from the Naganoken Hyōgu Kyōji Naisō Kyōkai 長野県表具経師内装協会.

- Tanuki Procuring Sake on a Rainy Night 夜雨の客, by Komatsu Hitoshi 小松均 (1902-1989), Museum of Modern Art in Shiga 滋賀県立近代美術館蔵. Photo SCCP; also see The Museum of Modern Art, Shiga Prefecture.

|

|

Tokkuri 徳利

|

|

What About Tanuki’s Sake Flask?

Tanuki artwork commonly portrays the creature holding a sake flask (tokkuri 徳利) in his right hand, but sometimes the flask appears in the left hand (no significance should be attributed to this difference). The sake flask depicted today on nearly all Tanuki ceramic statues is commonly traced back to a stanza from a popular old children's song in the Osaka and Kyoto sake-brewing areas. Although the exact date is unclear, the modern Association of Shigaraki Ceramic Companies as well as authorities at the Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park (SCCP) believe it surfaced sometime in the late Muromachi era (late 16th century). Whatever its origins, the stanza was well known by the early 18th century and goes like this:

- Ame no shobo shobo furu ban ni, mameda ga tokkuri motte sake kai ni

雨のしょぼしょぼ降る晩に 豆狸(まめだ)が徳利持って酒買いに.

Roughly translated, it means "On nights of non-stop drizzling rain, a small tanuki (mameda 豆狸) comes with a sake flask (tokkuri) to procure sake."

- There is actually a second part to the verse:

酒屋の前で ビンめんで. 帰って お母やんに怒られた or

酒屋の前で ビンめんで. 帰って お父さんに怒られた

Roughly translated, it means “In front of the sake shop a small tanuki dips his flask; and then gets into hot water (trouble) when the shop-owner's wife returns [or the shop owner himself].

- The Association of Shigaraki Ceramic Companies also adds: "From the late 16th century onward, the Nada brewing region [Osaka-Kyoto-Kobe area] was a center of sake production in Japan. The common folk came with tokkuri in hand to procure sake from the barrels of the brewers and then returned home. They often came with their children, who were allowed to perform the pouring. This popular practice was probably the origin of Tanuki okinomo 置物 (decorative carvings) known as Sake Kai Kozō no Tanuki 酒買い小僧の狸 [lit. = Tanuki as youthful Buddhist acolyte, or errand boy, procuring sake]. Additionally, the Nada brewers began to spread the story that delicious sake could only be made at breweries inhabited by a mameda 豆狸 (small tanuki)."

- More about Rain and Tanuki. The Chinese charageter Mái 霾 (Jp. = Bai), which means misty or foggy, is composed of two characters 雨 + 貍 -- the radical for rain 雨 and the old character for tanuki 貍. In the Japanese text Shinchomonshū Ryakki 新著聞集畧記 (circa 1700), we learn about an old spook monk who lived nearly 200 years at a certain monastery. But when he was killed by a dog, his true mujina form was revealed. Before his death, the mujina had written some unreadable characters and included a red seal containing the character 霾 (rain 雨 + tanuki 貍). The author of the Shinchomonshū adds: "In Japan as well as in China there are a great number of legends in which tanuki and mujina transformed themselves into men and discussed all kinds of things........these animals live in holes, yet they know when it will rain. This is all due to the supernatural power of the tanuki and mujina. But it is a strange fact that the old rnujina of this legend, who had lived for such a long time among men and possessed such enormous magical power, could be killed by a mere dog." <see De Visser , page 77-78, for full story in English>

Sources: Association of Shigaraki Ceramic Companies // Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park // Yakimono (Ceramics) Guide from Asahi.com. <Above translations by Schumacher>

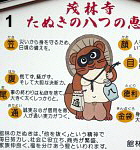

What About Hachi ㊇ Symbol on Tanuki’s Sake Flask?

Known as the Maru Hachi まる八 or the Maru Hachi Tokkuri まる八徳利, it refers to the symbol for “Eight” (hachi 八) drawn inside a circle ㊇ on the sake flask carried by Tanuki. Note, however, that the circle is often omitted in modern artwork. The emblem originated in the Edo period and is the crest-of-armor (mon 紋) for the branch of the Tokugawa 徳川 family controlling the old province (kuni) of Owari 尾張 (present-day Nagoya City and Aichi Prefecture) -- the most powerful Tokugawa domain outside the shogunate itself. It stands for the eight Owari districts controlled by the clan in those bygone days. In 1907, it was adopted as the emblem of Nagoya City. However, the Maru Hachi ㊇ wasn’t introduced to Tanuki artwork until the early 20th century. Since it was a trusted emblem of Edo-era Japan, artists likely incorporated the motif as a visual ploy to ease Tanuki’s procurement of sake. The Maru Hachi ㊇ should not be conflated with the modern-day commercial grouping known as Tanuki’s Eight Virtues. The latter is a contemporary contrivance of business firms, temples, and cities selling Tanuki merchandise. As one of the eight, the sake flask supposedly symbolizes gratitude for one's daily food and also the merits of eating and drinking in moderation. Wow !! Tanuki has completely shed his evil ways and is now a champion of gratefulness and restraint. That’s powerful shape-shifting !! <Source: Association of Shigaraki Ceramic Companies>

|

|

Tsū 通

|

|

What About Promissory Note Tanuki Never Pays?

Known as the Tsūchō 通長 or Chōzura 帳面, and commonly written with just one character Tsū 通, it represents Tanuki’s accounting ledger (his unpaid bills). Like the fox, Tanuki can cast powerful illusions. Both creatures can turn inanimate objects into gold and silver -- they can turn pebbles, dirt, and leaves into fake money or horse excrement into a delicious-looking dinner, or create mirages that fool the unwary into seeing phony cities and palaces. For example, the Fox-Haunting Record (Kobi no Ki 狐媚記), a 12th century work by Ōe no Masafusa 大江匡房 (1040-1111), mentions a fox who bought a house with gold, silver, and silk, but afterwards the unlucky seller was left only with "old straw sandals, clogs, tiles, pebbles, bones, and horns." <see De Visser, p.34> The same document mentions haunting foxes who made rice from horse dung and vegetables from cow bones. <p. 147> The key point here is Tanuki’s ability to cast illusions. He pays for his food and drink and merriment with seemingly real money, but once he departs, the money returns to its original worthless shape. The idea of Tanuki’s fake money (represented by his promissory note-bag) did not appear in Tanuki artwork until the early 20th century. Today, however, Tanuki’s accounting ledger is one of his so-called Eight Virtues (a modern-day commercial construct), wherein it symbolizes honesty (gaining the trust & confidence of others). That’s serious illusory magic !!

What About Tanuki’s Large Scrotum?