|

|

|

|

CALLIGRAPHY

Literally “The Way of Writing”

書道 = Shodō, Shodo, Shodou, Shodoo

ORIGIN: CHINA

For more calligraphy, please see photo tour of Bonbori (paper lanterns)

|

|

Confucian concepts still

serve as primary themes in calligraphy in China & Japan

道 tao; path, right way

仁 ren, benevolent

徳 de, virtuous

禮 li, propriety

義 yi, morality

忠 zhong, loyalty

恕 shu, reciprocity

信 xin, trustworthy

命 ming, destiny, fate

天 tien, heaven, above

理 li, priciple

* Chinese pronunciations *

|

|

INTRODUCTION. Calligraphy has a long and distinguished history in China, and this enthusiasm has extended to those nations who imported China’s writing system. Japan adopted Chinese ideograms most vigorously after the introduction of Buddhism to Japan in the mid-6th century, but the art of calligraphy was not pursued in Japan until the early years of the Heian era (+794-1185), when Japan’s so-called Three Great Brushes (Sanpitsu 三筆) began practicing calligraphy as an art. Nonetheless, the great watershed in Japanese calligraphy (in my mind) did not occur until the widespread propagation of Zen Buddhism (Chinese in origin) early in the Kamakura Era (+1185-1333). The contribution of Zen to Japanese culture is profound, and much of what the West admires in Japanese art today can be traced to Zen influences on Japanese architecture, poetry, ceramics, painting, calligraphy, gardening, the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, & other crafts. INTRODUCTION. Calligraphy has a long and distinguished history in China, and this enthusiasm has extended to those nations who imported China’s writing system. Japan adopted Chinese ideograms most vigorously after the introduction of Buddhism to Japan in the mid-6th century, but the art of calligraphy was not pursued in Japan until the early years of the Heian era (+794-1185), when Japan’s so-called Three Great Brushes (Sanpitsu 三筆) began practicing calligraphy as an art. Nonetheless, the great watershed in Japanese calligraphy (in my mind) did not occur until the widespread propagation of Zen Buddhism (Chinese in origin) early in the Kamakura Era (+1185-1333). The contribution of Zen to Japanese culture is profound, and much of what the West admires in Japanese art today can be traced to Zen influences on Japanese architecture, poetry, ceramics, painting, calligraphy, gardening, the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, & other crafts.

In calligraphy, the brush line that is sweeping and fluid -- spontaneous rather than predictable, irregular rather than regular -- is highly treasured. To paraphrase Alan Watts, much of Zen art is the “art of artlessness, the art of controlled accident.” Below I present some of my favorite brush work, almost all by contemporary artists. This is followed by a brief history of calligraphy in China and Japan.

JAPANESE PATRON DEITY OF CALLIGRAPHY

Tenjin shrines, especially those devoted to Sugawara no Michizane 菅原道真 (+845 - 903 AD), are closely associated with calligraphy. Michizane (a courtier in the Heian period) was deified after death, for his demise was followed shortly by a plague in Kyoto, said to be his revenge for being exiled. Michizane is the Japanese patron deity of scholarship, learning, and calligraphy. Every year on the 2nd of January, students go to his shrines to ask for help in the tough school entrance exams or to offer their first calligraphy of the year. Egara Tenjin (in Kamakura) is one of the three most revered Tenjin Shrines in Japan, and among the three largest. The other two are Dazaifu Tenmangu (near Fukuoka; Dazaifu is where Michizane was exiled), and Kitano Tenjin in Kyoto (Michizane's birthplace). Click here for more on Japanese shrines.

BUDDHIST PATRON DEITY OF CALLIGRAPHY BUDDHIST PATRON DEITY OF CALLIGRAPHY

Monju Bosatsu 文殊菩薩. (Sanskrit = Manjushri or Manjusri). The Guardian of Buddhist Law, the Voice of the Law, the Wisest of the Bodhisattva. In Japan, students pay homage to Monju in the hopes of passing school examinations and becoming gifted calligraphers.

JAPANESE MYTHS INVOLVING CALLIGRAPHY

Japan's popular Fire Festivals, held around January 15 each year, are also closely associated with calligraphy. Shrine decorations, talismans, and other shrine ornaments used during the local New Year Holidays are gathered together and burned in bonfires. They are typically pilled onto bamboo, tree branches, and straw, and set on fire to wish for good health and a rich harvest in the coming year. At these events, children throw their calligraphy into the bonfires -- and if it flies high into the sky, it means they will become good at calligraphy.

|

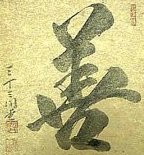

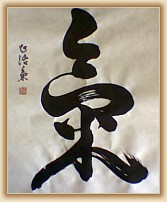

ZEN. Character for Good, Goodness, Virtue

|

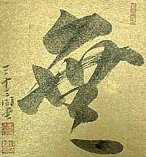

MU. Character for Nothingness, Emptiness, Void

|

|

1986. Brushed by young Buddhist monk at Renge-ou-in (Rengeō-in) 蓮華王院, more popularly known as Sanjusangendo (Sanjūsangendō) 三十三間堂, one of the most impressive of all Buddhist temples in Kyoto. The temple houses the Kannon of 1000 hands and is said to contain 33,333 of her images. The fluid sweeping brush strokes invoke a sense of vitality and spontaneity. When watching him brush this character, it seemed as though his hand and arm were dancing rather than writing.

|

1986. Brushed by same young Buddhist monk as first image above. Again note the uninterrupted sense of motion and fluidity of brush. Despite the negative connotations of this term in English, the term in Japan and China has glorious overtones, for it represents the principle of “going back to one’s nature,” of forgetting the forms of the material world, of finding enlightenment by discarding the mundane world and all its concepts. Be nothing, and become everything !

|

|

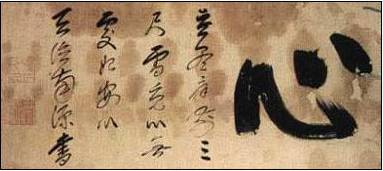

The large character is the word for “kokoro 心,” translated as heart, soul, spirit, or mind. This 17th century Japanese brush and ink handwriting, with its relaxed Zen spontaneity, is one of the exercises practiced by Zen monks today. Photo courtesy of: www.buddhanet.net.

Asian Art Musuem (San Francisco)

Below Text & Photos from the Musuem

http://www.asianart.org/elegantgathering.htm

Chn. = Xiyuan Yaji, Jp. = Seiengashuu 西園雅集, English = Elegant Gathering in the Western Garden. This refers to a tradition among members of China’s intellectual elite who would informally gather to debate with art rather than words. The Elegant Gathering Exhibition features 80 superb masterworks of Chinese calligraphy and painting carefully drawn together by generations of the fascinating Yeh family -- scholars, statesmen, and passionate practitioners of the Xiyuan Yaji tradition. <end quote Asian Art Museum>

One widely known member of China’s Elegant Gathering was So Tōba 蘇東坡 (1036-1101), aka So Shoku 蘇軾. His Chinese name was Su Dongpo 蘇東坡. For details on this Chinese artist, see JAANUS.

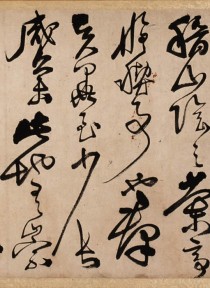

Orchard Pavilion Preface (Lanting xu) in cursive script (Ch = caoshu).

Handscroll, ink on paper. Dated +1629, by Gui Changshi (+1574–1645).

China, another source +1573–1644, Ming Dynasty (+1368–1644).

Gift of the Yeh Family Collection, R2002.49.36.A

“Duojing Lou” calligraphy in semi-cursive script.

Signed Mi Fu (+1051–1107). Album of twelve leaves.

Ink on paper. Gift of the Yeh Family Collection, 2004.31

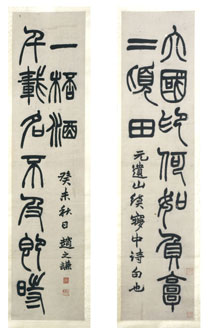

Couplet with commentary in seal and semi-cursive scripts.

Dated 1883, by Zhao Zhiqian (+1829–1884).

Pair of hanging scrolls, ink on paper.

Gift of the Yeh Family Collection, F2002.2.12.1-2

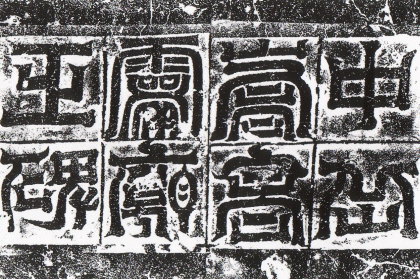

STONE RUBBINGS

www.mingeikan.or.jp/english/html/painting-pt_14.html

From China (Henan), +456 AD

Length 21.7 cm, Width 43 cm

Japanese Calligraphy - History

The Three Brushes, The Three Traces

Below text adapted from japanese.about.com story

One can trace Shodō 書道 (calligraphy; lit. “way of writing”) to China, where the master Wang Xizhi is credited with the creation of the art. Shodo was first introduced into Japan in the 8th century. The early Heian contemporaries Kukai 空海, Emperor Saga 嵯峨天皇, and courtier Tachibana no Hayanari 橘逸勢 are respectfully known as the Sanpitsu 三筆 (Three Great Brushes), and their calligraphy is considered a true representation of Chinese calligraphy's timeless beauty. In Japan’s 10th and 11th centuries, these three were succeeded by the Sanseki 三跡 (Three Traces) -- Ono no Toufuu 小野道風 (Yaseki Style 野跡), Fujiwara no Sukemasa 藤原佐理 (Saseki Style 佐跡), and Fujiwara no Yukinari 藤原行成 (Gonseki Style 権跡). These three masters developed the first Wayō 和様 (lit. “uniquely Japanese”) calligraphy styles. Fujiwara no Yukinari's Gonseki style led to the creation of the Sesonji school. Ono no Toufu’s calligraphy served as an archetype for the Shoren (Shōren) school, which later became the Oie style of calligraphy. The Oie style was used for official documents in the Edo period and was the prevailing style taught in the Terakoya 寺子屋 schools of that time. <end adapted text>

Main Calligraphy Styles in Japan

- Kaisho 楷書. Formal square script, or block style. This style is used in modern newspapers, magazines, books, and most publications. It is the same script used at this web site.

Kaisho Kaisho

- Gyosho 行書 (Gyōsho). Semi-cursive style; not as stiff as Kaisho nor as fluid as Sosho, and used for special effects in modern-day publications.

Gyosho Gyosho

- Sosho 草書 (Sōsho). Cursive script. Also called Grass script. Flowing style, with slender lines, and composed with rapid fluid strokes. This is the type most often used in formal Japanese calligraphy.

Sosho Sosho

- There are many others, like the Seal Script (Jp = Tensho 篆書) used for Japanese chops (name stamps), the Edo Script used in advertisements, etc. Most personal computers in Japan are installed with dozens and dozens of font sets.

Seal Seal

Edo Edo

Main Calligraphy Styles in China

- Grass Script (Jp = Sosho, Sōsho 草書)

- Seal Script (Jp = Tensho 篆書)

- Square script (Jp = Reisho 隷書)

- Mixed script (Jp = Zattaisho 雑体書)

Kukai 空海 and Calligraphy in Japan

Kukai 空海 (Kūkai; +774-835), also known as Kobo Daishi 弘法大師 (Kōbō Daishi), is one of Japan’s most beloved historical figures. He is also one of the Three Brushes (Jp = Sanpitsu 三筆 or Three Great Calligraphers) of Japan. He studied China’s main scripts while visiting China in the early 9th century, as well as the Sanskrit Siddam script. On his return from China, he founded Japan’s Shingon 真言 sect of Esoteric Buddhism 密教 (Mikkyo (Mikkyō). He played an active role in many fields, performing rituals for the emperor, constructing a large reservoir in Shikoku for the common people, and establishing the first school for common citizens. His legend is riddled with folklore. He is credited with everything from inventing Japan’s kana script to introducing homosexuality. He is one of Japan’s most celebrated calligraphers, and supposedly published Japan’s first dictionary. He became a major patron of the arts, and reportedly founded hundreds of temples across Japan. The Shikoku Pilgrimage to 88 Sites is a popular pilgrimage attributed to Kukai.

|

Baku (Jp. Pronunciation)

Shaka’s Seed Syllable

Ban (Jp. Pronunciation)

Dainichi’s Seed Syllable

Kiriku (Jp. Pronunciation

Amida’s Seed Syllable |

|

Kukai, Sanskrit Seed Syllables, Siddham, & Bonji Kukai, Sanskrit Seed Syllables, Siddham, & Bonji

In Japan, the generic term for "Sanskrit" is Bonji (梵字) or Bongo (梵語). The Japanese word for Seed Syllable is Shuji 種字 (Sanskrit = Bijaksara). In Japan, Sanskrit seed syllables are written in a script called Shittan 悉曇 (Sanskrit = Siddham). In Japanese Buddhist statuary, Buddhist deities are typically assigned a special seed syllable, one that is often inscribed somewhere on the statue or halo. Deities are also assigned mantras (Jp. = Shingon 真言) that contain these seed syllables -- the mantra is a magical incantation, a secret prayer, a special chant used to invoke the essence of the deity. Furthermore, Japan's esoteric sects also employ a mandala called the Seed-Syllable Mandala (Shuji Mandara 種字曼荼羅), in which the deities are symbolized by their individual seed syllables. A special version of this mandala, known as the Shiki Mandara (Shiki Mandara 敷曼荼羅) is used in initiation rites among esoteric sects. The initiand casts a flower onto the spread-out mandala, and the seed syllable on which it falls then becomes the patron deity of the intiand.

Sanskrit seed syllables are easy to spot in Japan. They are found on Japanese Buddhist amulets, gravestones, religious statuary, mandala artwork, and other objects, both old and new. By tradition, the introduction of seed syllables to Japan is credited to Kukai, who studied the main Chinese calligraphic scripts and Sanskrit Siddam while visiting China in the early 9th century, and brought back copies of the Seed-Syllable Mandala (see prior paragraph). Today he remains one of Japan’s most acclaimed calligraphers.

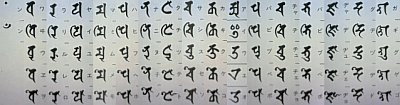

Over time, Kukai's Sanskrit syllabary was modified to better fit the Japanese lexicon. Since the time of Jogon (Jōgon) 浄厳 (+1639-1702), the Japanese-Sanskrit syllabary has traditionally consisted of 50 phonetic sounds (五十字門). A chart of the 50 is shown below.

Courtesy www.kuubokumon.com/bonji.html

Please visit above link for much larger version

Other Sanskrit-Related Sites

MORE ON JAPANESE CALLIGRAPHY

Somyo, Sōmyo, Soumyou 草名

http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/s/soumyou.htm

Also read Sona, Souna. A signature in cursive script. During the Nara period, signatures were written in formal square Kaisho 楷書 script. The style changed to semicursive or Gyousho 行書 script during the Heian period, and later to cursive script, sousho 草書, where two characters were combined into one to form a symbol. During the Fujiwara period, this form of signature appeared in the opening paragraphs of letters. Considered to be similar to and perhaps an early form of a Kaou 花押.

Genpitsu 減筆

http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/g/genpitsu.htm

Ch: jianbi. Often Genpitsubyou 減筆描. Also Ryakuhitsu 略筆. Lit. abbreviated brush drawing. An ink painting technique that employs a minimum of brush strokes to capture the essential features of an object, human figure, or scene. Of the three categories of brushwork (shin gyou sou 真行草) it is closest to the cursive style (sou) well suited for symbolic, suggestive renderings. Genpitsu is thought to have originated in China during the late Tang dynasty (+618-907) and flourished during the Song dynasty (+960-1279). Liang Kai 梁楷 (Jp: Ryou Kai late +12-13c) is said to have perfected this technique, and many of his figure paintings are prime examples. One such painting is his "Li Po reciting" (Ri Haku ginkou-zu 李白吟行図), a hanging scroll in Tokyo National Museum. Chinese genpitsu paintings were greatly admired and imitated by Japanese painters, especially during the Muromachi period. The technique is one of the eighteen types of figure portrayal, jinbutsu juuhachibyou 人物十八描.

Ashide 葦手

http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/a/ashide.htm

Lit. 'reed-hand script'. A decorative, pictorialized style of calligraphy, de 手, developed during the 9c in which cursive characters are disguised in the shape of reeds, ashi 葦, streams, rocks, flowers, birds, etc. A marsh scene with ashide characters was a motif frequently used in the under-drawings, shita-e 下絵, to decorate the paper of poetry anthologies and Buddhist scriptures or as the designs on textile and lacquer-ware. The term appears in literature from the 9th c onward. In the late 10c, The Tale of The Hollow Tree (UTSUBO MONOGATARI 宇津保物語), ashide is defined as one of several recognized forms of calligraphic script. Several extant examples of ashide date from the 12c. The decoration in underdrawing of 1160 in The Collection of Chinese and Japanese Poems for Singing (WAKAN ROUEISHUU 和漢朗詠集, Ministry of Cultural Affairs), with calligraphy written by Fujiwara no Koreyuki 藤原伊行, shows the fully developed stage of ashide. After the 13c, the term came to be applied loosely to mean: 1) a picture in which ashide characters were included; or 2) a type of pictorial puzzle or rebus using ashide letters and pictorial elements as clues to a poem (see uta-e 歌絵). These representations are also called reed-hand-script paintings, ashide-e 葦手絵, and they were no longer limited to marsh landscapes. For example, decorative cursive characters are found in a tree in the late 13c illustrated handscroll of The Lord Takafusa's Love Songs (Takafusakyou tsuyakotoba emaki 隆房卿艶詞絵巻, National Museum of Japanese History, Chiba prefecture).

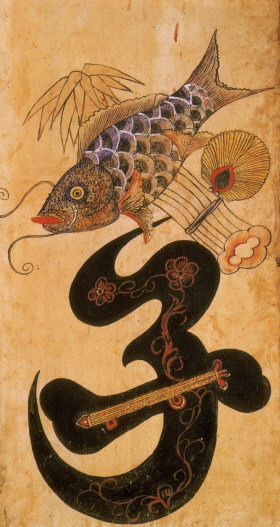

MOJI-E 文字絵

Pictorial Calligraphy. Ko (character for "child")

Yi Dynasty Korea, +19th Century, Length 77 cm

Photo Courtesy The Japan Folk Crafts Museum

Moji-e 文字絵 = Pictorial Calligraphy

Below text courtesy of JAANUS

A picture with the Japanese syllabary cleverly used as part of the motif. Another type of moji-e was called ashide-e, where entwined grass, flowers or water motifs took the form of Japanese syllables. These were popular during the Heian period. In the Edo period, it became popular to cleverly arrange letters in the folds and outlines of the garments worn by samurai or beautiful women in the prints. This device can be seen in ukiyo-e by Torii Kiyomasu (fl.c. +1696-1716), paintings by Okumura Masanobu (+1686-1764) and picture calendars (e-goyomi) by Kiyomasu II, Nidai Kiyomasu (+1706-63). Single-sheet multi-color moji-e also survive by Isoda Koryuusai (fl.mid +1760s-80s), Katsukawa Shunshou (+1726-92) and Katsushika Hokusai (+1760-1849).

|

|

|

|

Stylized form of Ki / Chi

|

|

|

Traditional form of Ki / Chi

|

|

|

Simplified form of Ki / Chi

|

|

|

|

KI (Chi, Ch’i, Qi)

Calligraphy by Afaq Saleem from Holland

(Martial Artist and Calligrapher)

Afaq’s Web Page & Estore

|

Ki (Chi, Ch’i, Qi)

Vital Energy, Life Force, Breath, Spirit

Roughly equivalent to the Sanskrit Prana,

the peculiarly unforced energy associated with breath.

|

|

|

|

|

|

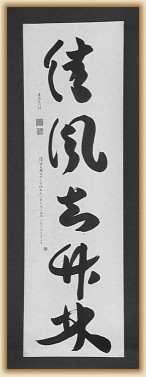

Holy Wind through the Bamboo Trees

by Afaq from Holland

(Martial Artist and Calligrapher)

Afaq’s Web Page & Estore

|

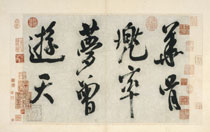

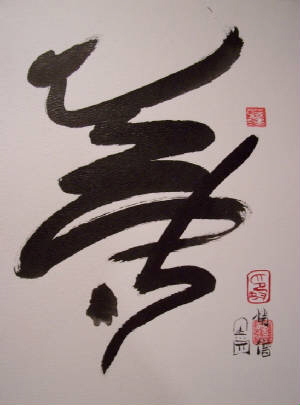

DREAM (Japanese = Yume)

Calligraphy by Qiao Seng, a Zen artist.

The hand-painted seal says “Dreaming of Butterflies.”

His artwork can be purchased by visiting his site.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sake - Japanese Nihonshu, or Rice Wine

Drawn by Yasutaka Daimon’s father

|

Aji - Taste

(scanned from a match book)

|

Painting at Ryutakuji

A Famous Zen Temple in Japan

|

|

|

|

|

|

Calligraphy by Steve Weiss. Says Steve: “This piece reads KAN 関, meaning ’barrier.’ Done in sōsho style, it was inspired by a piece by Ōmori Sogen 大森 曹玄 (1904-1994), wherein he defined it as the "perceptive barrier" that all students of Zen must cross over. If you think about KAN defined as a barrier from a Buddhist perspective, nothing really exists, no barriers at all! What Ōmori Sogen was saying was that one has to develop the perception to penetrate this invisible barrier (created by man himself) in order to realize one's Buddha nature.”

|

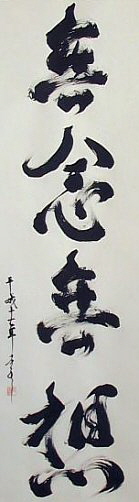

Calligraphy by Steve Weiss. Says Steve: “This piece reads MU NEN MU SŌ 無念無想 and is an old martial art saying meaning ’no thoughts no desires.’ It is a highly developed state of mind where thinking about your opponent or technique has been transcended.”

|

|

MORE ON CALLIGRAPY

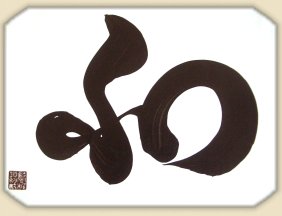

WA = Harmony. Calligraphy by Afaq from Holland. Afaq’s Web Page & Estore

|

|