|

|

|

|

Maneki Neko 招き猫 or 招猫

Lucky Beckoning Cat or Inviting Cat

What’s New (April 2011)

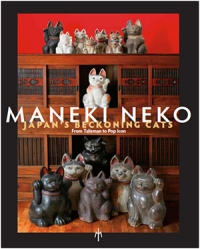

New Book & Exhibition on Maneki Neko from the Mingei International Museum

|

|

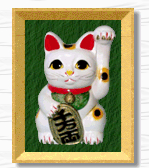

Photo of Japan’s Lucky Maneki Neko

Statue found at Ofuna Outdoor Food Market

in Kanagawa Pref. (near Kamakura City)

Taishō Era 大正時代 (1912-1926)

Wood, Approx. 30 cm in height.

The cat’s right leg is shown atop a lucky mallet inscribed with the character Fuku 福, which means luck or prosperity.

Japan’s Maneki Neko are often shown carrying koban (gold coins from the Edo Period). Traditionally worth one ryō each (a measure of value in its day), the three koban coins held by this lucky cat statue are worth much more. One of the coins is worth one million ryō 両, another worth 10,000 ryō, and yet another worth 1,000 ryō. This statue is prominently displayed by a food merchant who does business at the Ofuna food market -- it is meant to bring the merchant prosperity, to greatly expand the store’s profits.

|

|

MANEKI NEKO (literally "beckoning cat") is one of the most common lucky charms in Japan, designed to attract business and promote prosperity. Found frequently in shop windows, the Maneki Neko sits with its paw raised and bent, beckoning customers to enter. There are countless superstitions about cats in Japan (as there are in many other nations), assigning it either good or bad powers, benevelent or malevolent attributes. Some Japanese believe that when a cat washes its face and paws in the genkan (parlor), company's coming. This belief may be a "Japanized" version of the 9th-century Chinese proverb: "If a cat washes its face and ears, it will rain." This may sound far fetched, but many other nations hold equally curious beliefs in the soothsayer magic and socery of the feline. See resources for worldwide cat lore.

HISTORICAL NOTES HISTORICAL NOTES

It is commonly believed that the Maneki Neko became popular in the latter half of the Edo Period (1603 - 1867), although this lucky cat is rarely mentioned by name in era documents. By the Meiji Period (1868 - 1912), however, it begins to appear with great regularity in publications and business establishments.

One of the most plausible reasons for its rapid rise to popularity in the Meiji Period involves the sex industry. In the secluded Edo Period, during which Japan closed its doors to the outside world, an indigenous "amusement" culture grew side by side with the expanding power of the merchant class.

Special zones called Yūkaku 遊廓 (soap land in modern parlance) sprang up to provide female companionship (prostitution) and other forms of merriment. Many "houses of amusement" were equipped with a "good-luck shelf" on which were displayed lucky charms in the shape of the male sexual organ. Even today, various localities in Japan still hold an annual fertility festival, during which a gigantic wooden penis is paraded through the streets as an offering for good harvests and prosperity.

But with the opening of Japan by the West, and the establishment of the Meiji government in 1868, Japan's reliance on agriculture declines, and the country turns aggressively toward modernization. In its drive to establish a modern nation state, and in a ploy to minimize the negative image of Japan among the largely Christian Western world, the Meiji government prohibits the production, sale, and display of the artificial male sexual talisman beginning in 1872.

These charms soon disappear from the good-luck shelf, but there disappearance coincides with the rapid spread of Maneki Neko charms. In the Yūkaku zones, poster images from the era show women beckoning like a cat. Restaurants soon pick up the habit, and the cat is out of the bag (so to speak)!

Says Katherine M. Ball, author of Animal Motifs in Asian Art (1927): “While the cat, with many nations, has been associated with women, particularly old women, in Japan, the geisha, ‘singing girl,’ appears to have been selected for this distinction, doubtless due to the witchery she exercises over the opposite sex.” <end quote, p. 154>. Says author F. Hadland Davis in Myths and Legends of Japan (1913): “B.H. Chamberlain write in Things Japanese: ’Among Europeans an irreverent person may sometimes be heard to describe an ugly, cross old woman as a cat. In Japan, the land of topsy-turveydom, that nickname is colloquially applied to the youngest and most attractive - the singing girls.’ The comparison seems strange to us, but the allusion no doubt refers to the power of witchery common alike to the singing-girl and the cat.” <end quote>

OTHER CAT LORE FROM JAPAN

From Animal Motifs in Asian Art (1927) by Katherine M. Ball, Published 1927:

- In Japan, while the wild cat is indigenous, the domestic animal -- known by the name of Neko -- is an importation from China. To the Emperor Ichijō 一条天皇 (987-1011) belongs the credit of introducing the little creature to this country; and so costly was it that only the court could indulge in the extravagance. From the diary of Fujiwara no Sanesuke 藤原実資 of the 10th century may be learned the degree in which this household pet was prized. (page 152; which also describes Fujiwara’s diary entry)

- Japan has many legends of cat sorcery, in which the neko-mata, “cat demon,” is described as a huge creature with forked tail and possessing the power to assume human form and bewitch mankind. Of these legends, the best known is that of Nabeshima no Neko, “The Cat of Nabeshima.” (pages 152-153; see those pages for the Nabeshima tale)

- Cat magic in Japan has many different forms. It may be malevolent, playful, or beneficial. For example, the tortoise-shell cat is believed by seafaring men to be lucky since it keeps the Obake (ghosts) away, as well as all rats. Again, a simple and popular form of magic exercised for protection is connected with an image of a cat generally made from some sort of clay, but sometimes of papier-mache and known as the Maneki Neko, “Inviting Cat.” This image is used as an amulet designed to attract business and promote prosperity. It is to be found at the entrance of restaurants and shops, where, with its ingratiating feline qualities and uplifted paw, it may invite customers and bid them enter. <page 154>

- The Maneki Neko is likewise regarded as a worthy toy for children, for it is thought to be able to avert evil, particularly illness, for which reason it is worn by them about the waist to keep off pain. And not only the image of the animal, but the ideograph by which its name is represented, is regarded as efficacious, for which reason it is so commonly seen in the homes of cocoon-breeders and silk-weavers, who ever are in serious need of some remedy for rats. <page 154>

- In the Chinese classification of animals according to the Yang and Yin, the masculine and positive, and the feminine and negative principles of nature, the dog is assigned to the Yang and the cat to the Yin, for the Chinese claim that the cat has supernatural powers for working evil, while the dog possesses similar powers for counteracting it. Yet notwithstanding this, both animals play a double role in legends of superstition, one in which as demons they are feared, and the other as worthy associates which render service to mankind. <page 150>

From Myths and Legends of Japan by F. Hadland Davis. Published 1913:

- The Japanese cat, with or without a tail, is very far from being popular, for this animal and the venomous sepent were the only two creatures that did not weep when the Lord Buddha died. <page 264)

- Japanese cats seem to be under a curse, and for the most part they are left to their own resources, resources frequently associated with supernatural powers. Like foxes and badgers, they are able to bewitch human beings. <page 264>

- The Japanese cat, however, is regarded with favour among sailors, and the mike-neko, or cat of three colours, is most highly prized. Sailors the world over are said to be superstitious, and those of Japan do their utmost to secure a ship’s cat, in the belief that this animal will keeep off the spirits of the deep. Many sailors believe that those who are drowned at sea never find spiritual repose; they believe that they everlastinly lurk in the waves and shout and wail as junks pas by. To such men the breakers beating on the seashore are the white, grapsing hands of innumerable spirits, and they believe that the sea is crowded with Obake (honourable ghosts). The Japanese cat tis said to have control over the dead. <page 264-265)

- Hanland also present other lore about Vampire cats (the Nabeshima tale mentioned above), and phantom cats.

- Another matter of interest -- in Buddhist teachings, the body of the cat can sometimes become the temporary resting place of the soul of very spiritual people.

(L) Ceramic Maneki Neko (M) Wood Maneki Neko (Edo Period)

(R) Cartoon Image from Corel Draw Collections

CAT COLORS

Among the various manifestations of the Maneki Neko charm, the most popular is tri-colored. Yet tri-colored male cats are rarely found among the world's cat population. Indeed, genetic studies show conclusively that a tri-color gene in male cats is quite rare. For this reason, perhaps, the tri-colored Maneki Neko is considered most lucky. White versions and black versions of the Maneki Neko are also popular. Some say white represents purity, whereas black cats have traditionally been considered lucky in Japan, able to ward off evil or cure illness in children. Today, the black Maneki Neko is reportedly gaining popularity among ladies to ward off stalkers. Various sites devoted to this lucky charm (see RESOURCES below) claim that the less-prevalent red-colored Maneki Neko is used to exorcise evil spirits and to combat illness, while gold-colored cats invite money and pink ones attract love. Nonetheless, in Japan's not so distant past, red and pink cats were thought to have supernatural powers and were avoided. Among the various manifestations of the Maneki Neko charm, the most popular is tri-colored. Yet tri-colored male cats are rarely found among the world's cat population. Indeed, genetic studies show conclusively that a tri-color gene in male cats is quite rare. For this reason, perhaps, the tri-colored Maneki Neko is considered most lucky. White versions and black versions of the Maneki Neko are also popular. Some say white represents purity, whereas black cats have traditionally been considered lucky in Japan, able to ward off evil or cure illness in children. Today, the black Maneki Neko is reportedly gaining popularity among ladies to ward off stalkers. Various sites devoted to this lucky charm (see RESOURCES below) claim that the less-prevalent red-colored Maneki Neko is used to exorcise evil spirits and to combat illness, while gold-colored cats invite money and pink ones attract love. Nonetheless, in Japan's not so distant past, red and pink cats were thought to have supernatural powers and were avoided.

Accoutrements - Red Collar, Bell, Apron, Coin

Probable Connection to Buddhist Tradition

The red collar with bell found on most Maneki Neko probably originated from a custom of the Edo Period. During those days, affluent ladies adorned their cats (an expensive pet at the time) with red collars made of hichirimen (Camellia Japonica, a red flower), and small bells were attached to the collar to help the owners keep track of their pets. Some Maneki Neko also wear an apron. Don't quote me on this, but one resource says it might stem from a custom involving the beloved Jizo Bodhisattva, the guardian of sick or dead children and expectant mothers . Even today, you will often come across a Jizo statue wearing a hat or bib or some other garment. Sorrowing mothers bring the little garments of their lost ones and dress the Jizo statue in hopes the kindly god will protect their child. Sometimes, too, a hat or bib has been gratefully offered by a rejoicing parent whose child has been cured of a dangerous sickness thanks to Jizo's intervention. And lastly, some Maneki Neko are carrying a koban (gold coin from the Edo Period). Worth one ryō (a measure of value in its day), the koban carried by the Maneki Neko is worth one million ryō 百万両 (see photo at top of this page). The red collar with bell found on most Maneki Neko probably originated from a custom of the Edo Period. During those days, affluent ladies adorned their cats (an expensive pet at the time) with red collars made of hichirimen (Camellia Japonica, a red flower), and small bells were attached to the collar to help the owners keep track of their pets. Some Maneki Neko also wear an apron. Don't quote me on this, but one resource says it might stem from a custom involving the beloved Jizo Bodhisattva, the guardian of sick or dead children and expectant mothers . Even today, you will often come across a Jizo statue wearing a hat or bib or some other garment. Sorrowing mothers bring the little garments of their lost ones and dress the Jizo statue in hopes the kindly god will protect their child. Sometimes, too, a hat or bib has been gratefully offered by a rejoicing parent whose child has been cured of a dangerous sickness thanks to Jizo's intervention. And lastly, some Maneki Neko are carrying a koban (gold coin from the Edo Period). Worth one ryō (a measure of value in its day), the koban carried by the Maneki Neko is worth one million ryō 百万両 (see photo at top of this page).

Paw Up (Left or Right)

According to research by the Maneki Neko Club in Japan, about 60% of all Maneki Neko talismans are lifting up their left paw, while the rest hold up their right. South paws are supposedly beckoning customers to enter the store, while right paws are supposedly attracting money and good fortune (e.g., piggy banks in the shape of the Maneki Neko hold up their right paw). The distinction seems somewhat dubious to me - don't more customers mean more money? According to the same source, most Maneki Neko in earlier days were lefties, but the growing lust for money in contemporary Japan means that more and more modern-day cat charms beckon with their right paw. Paw height is also of interest. The higher the paw, the more expansive the reach of the cat's lucky magic.

Paw Up (Front or Back)

The Maneki Neko made for export beckons by showing the back of its hand (as is customary in America and other nations). But the Maneki Neko made for domestic Japanese consumption beckons by showing the palm of its left hand, as is customary among the Japanese.

CAT LEGENDS

Courtesy of Japanese Bobtail (Eurocatfancy.de) and Maneki Neko Cat Club (J-Site).

Also see Myths & Legends of Japan (1913) and Animal Motifs in Asian Art (1927) for other stories.

Gōtokuji Temple, 17th Century

This is a well known Japanese story. There once was a poor monk at a poverty-stricken temple. He shared what little food he had with his pet cat. One day, Lord Ii Naotaka of the Hikone district near Kyoto was caught in the rain near the temple on his way home from hunting. Taking refuge under a nearby tree, he beheld a cat beckoning him to enter the temple compound. As soon as he ventured forth to investigate this strange cat, the tree was struck down by lighting. The lord quickly became the temple's patron, and the temple soon became prosperous. It was renamed Goutokuji Temple in 1697 - even today, the walls of this temple in Tokyo's Setagaya ward are adorned with paintings of bobtail cats. When the cat died, it was buried in Goutokuji's cat cemetery, and the Maneki Neko was made in honor of this magical cat. According to some, the Maneki Neko since that time has been considered an incarnation of the Goddess of Mercy, the deity who watches over and protects people in the earthly realm. The Goutokuji Temple today is home to dozens of statues of this legendary cat, and owners of lost or sick cats come to the temple to stick up prayer boards containing the image of the Maneki Neko. Says Cats & Kittens Magazine: “The walls of Tokyo's Gotokuji Temple, constructed in 1697, are adorned with paintings of bobtail cats, and two longhair bobtails are featured in a 15th-century painting that hangs in the Freer Gallery of Art in the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC.” <end quote>

Courtesan Usugumo, 18th Century

During the Edo Period, in the eastern part of Tokyo called Yoshiwara, there lived a courtesan named Usugumo. She loved cats, and kept her feline pet at her side constantly. One night, on her way to the powder room, her cat began tugging at the hem of her kimono violently, refusing to let go. The owner of the amusement house came to her aid, and suspecting the cat to be bewitched, lopped off its head with his sword. The head flew to the ceiling, where it killed a snake poised to kill Usugumo. She was terribly distraught by the wrongful death of her beloved cat. To make her feel better, one of her customers gave her a wood-carved image of the cat, which later gains popularity as the Maneki Neko.

Old Woman of Imado, 19th Century

There once was a poor old woman who lived in Imado (now eastern Tokyo). She kept a pet cat until severe poverty forced her to abandon it. Not long thereafter, the cat appeared to her in a dream and instructed her to make its image in clay. She obliged, and to her delight, people were soon asking to buy the clay statue. The more she made, the more they bought, and her poverty was replaced with prosperity.

Maneki Neko at Imado Jinja Shrine 今戸神社 in Tokyo. Photo this J-Site.

Common Sense Competition

Perhaps the least imaginative, but nonetheless compelling legend, involves two competing ramen shops doing business next door to each other. One sets a lucky cat in its window, and all the customers flood that shop. Well, at least until the shop next door gets its own Maneki Neko.

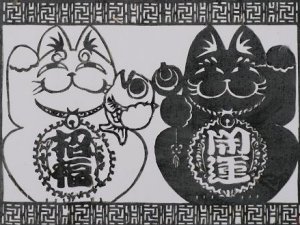

White cat holds lucky fish and wears bell saying 福助 (bringer of luck).

Black cat holds lucky mallet and wears bell saying Kaiun 開運 (also bringer of luck).

The imagery borrows from Ebisu and Daikokuten, two of Japan’s seven lucky gods.

Ebisu is often depicted holding a fish, while Daikokuten is often shown with a mallet.

Photo found on this J-site.

LEARN MORE

MANEKI NEKO. Japan's Beckoning Cats - From Talisman to Pop Icon. By Alan Scott Pate. Published 2011, 115 pages, 81 color photos. This book reveals the origins, history, lore and meaning of these alluring and enigmatically artful felines. With superb photographs and scholarly but accessible text by Alan Scott Pate, this book highlights the most important museum collection of Maneki Neko in the United States. The Billie Moffit Collection of Maneki Neko at the Mingei International Museum consists of some one hundred fifty-five examples from the 19th and 20th centuries. Representing a wide variety of media, from stone to iron, from wood to papier-mache, the collection presents an opportunity to explore in depth the world of the maneki neko. Purchase the book here or learn more about the collection and exhibition. MANEKI NEKO. Japan's Beckoning Cats - From Talisman to Pop Icon. By Alan Scott Pate. Published 2011, 115 pages, 81 color photos. This book reveals the origins, history, lore and meaning of these alluring and enigmatically artful felines. With superb photographs and scholarly but accessible text by Alan Scott Pate, this book highlights the most important museum collection of Maneki Neko in the United States. The Billie Moffit Collection of Maneki Neko at the Mingei International Museum consists of some one hundred fifty-five examples from the 19th and 20th centuries. Representing a wide variety of media, from stone to iron, from wood to papier-mache, the collection presents an opportunity to explore in depth the world of the maneki neko. Purchase the book here or learn more about the collection and exhibition.

|

|