|

|

|

|

|

Shugendō 修験道

Path to Mystic Powers

|

|

En no Gyōja 役行者

Father of Shugendō

|

|

|

&

|

|

|

Path to Mystic Power Via Ascetic Practices

Merger of Mountain Worship, Shamanism, Shintōism, Taoism, & Buddhism

This is a Side Page. Return to Sect Index.

|

NOTE: This page relies heavily on the research and assistance of Dr. Gaynor Sekimori, formerly of the Centre for the Study of Japanese Religions, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. When this story was first published (April 2009), she was also a visiting professor at Kokugakuin University (Tokyo, Japan). She has authored and translated numerous books and articles on Japan’s Shugendō religious traditions. NOTE: This page relies heavily on the research and assistance of Dr. Gaynor Sekimori, formerly of the Centre for the Study of Japanese Religions, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. When this story was first published (April 2009), she was also a visiting professor at Kokugakuin University (Tokyo, Japan). She has authored and translated numerous books and articles on Japan’s Shugendō religious traditions.

|

Shugendō (also spelled Shugendo) can be loosely translated as "path of training to achieve spiritual powers." Shugendō is an important Kami-Buddha combinatory sect that blends pre-Buddhist mountain worship, Kannabi Shinkō 神奈備信仰 (the idea that mountains are the home of the dead and of agricultural spirits), shamanistic beliefs, animism, ascetic practices, Chinese Yin-Yang mysticism and Taoist magic, and the rituals and spells of Esoteric (Tantric) Buddhism in the hope of achieving magical skills, medical powers, and long life. Practitioners are called Shugenja 修験者 or Shugyōsha 修行者 or Keza 験者 (those who have accumulated power) and Yamabushi 山伏 (those who lie down in the mountain). These various terms are typically translated into English as ascetic monk or mountain priest. Shugendō (also spelled Shugendo) can be loosely translated as "path of training to achieve spiritual powers." Shugendō is an important Kami-Buddha combinatory sect that blends pre-Buddhist mountain worship, Kannabi Shinkō 神奈備信仰 (the idea that mountains are the home of the dead and of agricultural spirits), shamanistic beliefs, animism, ascetic practices, Chinese Yin-Yang mysticism and Taoist magic, and the rituals and spells of Esoteric (Tantric) Buddhism in the hope of achieving magical skills, medical powers, and long life. Practitioners are called Shugenja 修験者 or Shugyōsha 修行者 or Keza 験者 (those who have accumulated power) and Yamabushi 山伏 (those who lie down in the mountain). These various terms are typically translated into English as ascetic monk or mountain priest.

As a general rule, this sect stresses physical endurance as the path to enlightenment. Practitioners perform seclusion, fasting, meditation, magical spells, recite sutras, and engage in austere feats of endurance such as standing/sitting under cold mountain waterfalls or in snow. Another particular practice of Shugendō devotees is to set up stone or wood markers (Jp. = Hide 碑伝) along mountain trails, presumably to leave proof of their mystical journeys up the mountain. There are also precise procedures the practitioner must observe when entering into any sacred mountain space (Jp. = Nyūzan 入山 or Sanpai Tozan 参拝登山), with each stage consisting of a specific mudra 確認印 (Jp. = Kakunin-in or hand gesture with religious meaning), mantra 真言 (Jp. = Shingon or sacred verbal incantation) and waka 和歌 (classical Japanese poem).

Says scholar Paul L. Swanson in Shugendō and the Yoshino-Kumano Pilgrimage: “Shugendō is a religious practice which took the form of an organized religion about the end of the Heian period (794-1184) when Japan's ancient religious practices in the mountains came under the influence of various foreign religions. This loosely organized sect includes many types of ascetics, including unofficial monks (ubasoku 優婆塞), peripatetic holy men (hijiri 聖), pilgrimage guides (sendatsu 先達), blink musicians, exorcists, hermits, diviners, wandering holy men, and others.” <end quote> Also see Shugendō & Mountain Religion in Japan (edited by Royall Tyler and Paul L. Swanson, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, Volume 16:2-3, 1989.

En no Gyōja, Father of Shugendō

The sect's most celebrated sage is En no Gyōja 役行者 or 役の行者. Also known as En no Ozunu 役小角 (or Ozuno), En no Shōkaku 役の小角, and En no Ubasoku 役優婆塞. Gyōja means ascetic, so En no Gyōja literally means "En the Ascetic." Ubasoku is the Japanese form of Sanskrit "upāsaka," meaning adult male lay practitioner or devotee or Buddhist layman. En no Gyōja's clan name, En, is also often read E; hence E no Gyōja, E no Shōkaku, E no Ozunu, etc.

He is recognized as the father of Shugendō. His posthumous title is Shinben Daibosatu 神辺大菩薩 (also read Jinben Daibosatsu and meaning Miraculous Great Bodhisattva), a title bestowed upon him in 1799 by Emperor Kōkaku 光格天皇 (reigned 1771-1840). At Kongōsan Tenhōrinji 金剛山転法輪寺, a Shugendō temple near Osaka, he is also considered a manifestation of Hōki Bodhisattva 法起菩薩. Artwork of En no Gyōja dates from the Kamakura period (1185-1332) onward, and is found most frequently among temples of the Shingon 真言 sect of Esoteric (Tantric) Buddhism (Mikkyō 密教), which was strongly influenced by mountain asceticism in Japan’s Ōmine 大峰 mountain range in the Yoshino-Ōmine-Kumano region.

This legendary holy man was a mountain ascetic of the late 7th century. Like much about Shintō-Buddhist syncretism, his legend is riddled with folklore. He was a diviner at Mt. Katsuragi 葛城山 on the border between Nara and Osaka. Said to possess magical powers, he was unjustly expelled to Ōshima 大島 (aka Itōshima 伊豆嶋 island) off the coast of Izu Province 伊豆国 in +699 on trumped-up charges of manipulating demons and using sorcery to mislead the people. Popular lore says he climbed and consecrated numerous sacred mountains. En no Gyōja is mentioned in old Japanese texts like the Shoku Nihongi 続日本紀 (compiled around +797) and the Nihon Ryōiki 日本霊異記 (compiled around +822).

According to the Nihon Ryōiki, he was born in the Katsuragi 葛城 mountains of Nara Prefecture, and hailed from the Kamo 賀茂 clan and the family Kamo-no-E-no-Kimi 賀茂役公. In the Shoku Nihongi, his name is given as En no Kimi Ozunu 役君小角 (also read E no Kimi Shōkaku). His clan had lived in this mountainous region for generations -- a verdant region with numerous varieties of medicinal plants. He reportedly gained a great knowledge of these medical plants and managed a garden in the area, but for some reason he was forced to give up his plot in 675 AD. But by this time he had already gained a reputation as a healer.

When his father died, he prayed to heaven to bless his mother with another child, for he hoped to depart to the mountains to pursue his practice. His mother subsequently gave birth to a son named Tsukiwakamaru 月若丸, and then Uzunu entered the Katsuragi mountains (at the age of 32 it is said) to begin sustained ascetic practice. Legend claims he practiced under the protection of mountain animals, and that he discovered valuable deposits of mercury and silver in the mountains.

In 699, according to most Shugendō legends, he was falsely accused of evil sorcery by a jealous disciple named Karakuni-no-Muraji Hirotari 韓国の連広足 and banished to Itōshima 伊豆嶋 island during the reign of Emperor Monmu 文武天皇 (reigned from 697 to 707). In a tale from the late-Heian-era Konjaku Monogatari Shū 今昔物語集, En no Gyōja was enraged by the hauteur of the god of Mt. Katsuragi (known as Hitokoto-nushi no Kami 一言主神). He punishes the god by trussing the deity up with spells and confining it to the bottom of the valley. Hitokoto-nushi then vents his displeasure by possessing Hirotari, who then lodges complaints in the capital that eventually lead to Ozunu’s banishment. Click here for the Konjaku Monogatari story as translated by Marian Ury.

Reference: Ury, Marian. Tales of Times Now Past. Sixty-Two Stories from a Medieval Japanese Collection. University of California Press, 1979. See pages 82-83. Purchase book here.

Marian Ury was a professor of comparative literature at the University of California, Davis. She specialized in medieval Japanese literature. She died of cancer on 25 April 1995 at the age of 62.

HOW E NO UBASOKU RECITED SPELLS AND EMPLOYED DEMONIC DEITIES. From Chapter 11, Story Three, in the Konjaku Monogatari. Translated by Marian Ury.

At a time now past, in our own country, in the reign of Emperor [Monmu *1] , there was a holy man named E no Ubasoku [*2]. He came from the village of Chihara in Upper Kazuraki District in Yamato Provice, and his clan name in secular life was Kamo E. For more than forty years he lived on Mount Kazuraki, wisteria bark his clothing, pine needles his food, and a mountain cave his home. He bathed in pure springs, cleansed his heart of defilement, and recited the spell of the Peacock King. [*3] There were times when, riding upon a cloud of five colors, he visited the grottoes of the immortals. By night he summouned to his service demonic deities and made them draw water and gather firewood. All beings obeyed him.

Now, the Bodhisattva Zao of Mount Mitake [*4] appeared in response to Ubasoku's devotions. Ubasoku therefore journeyed back and forth continually between Mount Kazuraki and Mount Mitake. In consequence, he assembled the demonic deities and said to them: ["Build a bridge from Mount Kazuraki to Mount Mitake for me to travel on. *5"] When they heard this, the demonic deities [all raised their voices *5] in lamentation, but he would not give way. They were vexed beyond measure, but they could not escape his torments, and so they brought together a great many boulders and began to erect a bridge. The demonic deities told Ubasoku, however: "We are hideous to look upon. We shall therefore build this bridge under concealment of night." Night after night they made haste to build. Ubasoku, however, summoned Hitokotonushi, the god of Kazuraki. "Why should you be ashamed to show yourself?" he said. "If that's how you feel about it, we won't build the bridge at all!" replied the god. Enraged, E no Ubasoku trussed the god up with spells and confined him in the bottom of a valley.

Subsequently Hitokotonushi entered into someone in the capital and speaking through this medium lodged an accusation. "E no Ubasoku has treacherous designs and is plotting to overturn the state." When the Emperor heard about this he was alarmed and despacthed an official to arrest Ubasoku, but Ubasoku flew up into the sky and could not be caught. The official thereupon arrested Ubasoku's mother. At the sight of his mother taken prisoner, he came forth of his own accord to be made prisoner in her stead. The Emperor pondered his offense and exiled him to the island of Oshima off the coast of Izu Province. An island it might be; bu he ran about on the surface of the ocean as though on dry land, and among the mountain peaks he flew just like a bird. During daylight he observed his exile out of respect for the throne, but by night he traveled to Mount Fuji in Suruga Province. He prayed that he might be released from his punishment. After three years, the Emperor heard that he was guiltless and summoned him to the capital.....

[The story breaks off here. We know from other tales that E no Ubasoku then went to the Chinese continent.]

Notes to Story

- Reigned 697-707; lacuna in the original.

- He is also known as E no Gyoja, E no Shokaku, and E no Ozunu. Ubasoku is the Japanese form of Sanskrit upasaka, a lay devotee. His clan name, E, is also often read En; hence En no Ubasoku, etc.

- The Peacock King is one of the Four Guardian Kings, supernatural protectors of the Dharma who are worshipped in the Tantric schools of Buddhism. The magical formulae associated with him were considered especially efficacious in averting natural calamity.

- Zao is a deity of hybrid Indo-Japanese origin; the mountain of which he is the patron is the highest peak in the Yoshino range and one of the holy mountains of the Shugendo cult, which considers E no Ubasoku its patriarch.

- The general sense of these two lacunae can be reconstructed from other versions of the story.

Others speculate that Ozunu's banishment was caused by disputes over the metal resources in the mountains where he practiced. Yet another legend contents that his mother was falsely accused of having a wicked romance with an elder cousin. She is arrested. Uzunu comes to her aid and is himself arrested, bound in straw ropes, and exiled to Izu. During these events, Tsukiwakamaru (Uzunu’s younger brother) is forced to sell flowers to make a living, but he unexpectedly meets the emperor, tells his story, and gains the emperor’s sympathy. Ozunu and his mother are then pardoned, but Ozunu decides to remain in the mountains.

The final years of this holy man are clouded in uncertainty. Says the Dungeon website: “Accounts which claim he did not die in 700 say he was pardoned in January 701. He returned to Mt. Katsuragi (where he captured Hitokoto-nushi no Kami, tied him up with an arrowroot vine, and locked him away at the bottom of the valley). Some months later, he either went to the Japanese mountains in Minō and there attained Nirvana, or he crossed to China. Other accounts profess that he was in fact released in 702, after which he either became a Sennin 仙人 (immortal) and flew away into the Great Sky, or he migrated to China with his mother.” <end Dungeon quote> In the Nihon Ryōiki 日本霊異記 (compiled around +822), one story (vol. 1/28) reports that the monk Dōshō 道昭 (629-700) met En no Gyōja in China in 701. See Bernhard Scheid below.

He reportedly traveled widely during his lifetime, establishing Shugendō sanctuaries at numerous locations, including the Ōmine 大峰 mountain range (Nara prefecture), Mt. Kinpusen 金峯山 (Nara prefecture), Mt. Minō 箕面山 (near Osaka), the Ikoma 生駒 mountains on the border of Nara and Osaka Prefectures (where he captured two demons who thereafter served him), and in Japan’s Izu 伊豆 and Tōkai 東海地方 areas.

|

Seated En no Gyōja by

Raijo 頼助. Wood.

H 80.3 cm. Muromachi Era.

Dated 1396. Kawai Dera

河合寺, Osaka.

Source: Taoism Art

|

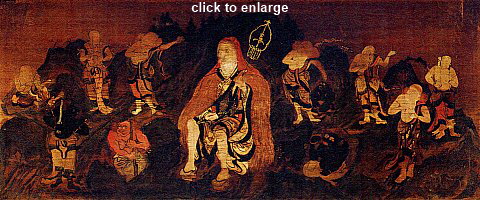

En no Gyōja, Eight Boy Attendants

& Two Demon Attendants (Zenki & Goki). 役行者八大童子前後鬼像.

Framed Panel, Color on Wood.

H = 57 cm, W = 125.9 cm. Kamakura Era, Dated 1331.

Rinnō-ji Temple 輪王寺, Tochigi.

Source: Taoism Art Catalog.

Reference: Taosim Art. Exhibit catalog published in 2009 by the Osaka Municipal Museum of Art together with the Yomiuri Shimbun, Osaka. Fabulous exhibit featuring approx. 420 Taoist-related art works. The exhibit was held in first in Tokyo, then Osaka and Nagasaki, between late 2009 and early 2010. A brilliant catalog. . 道教の美術

|

|

Shugendō Schools - Influence of Tendai & Shingon Shugendō Schools - Influence of Tendai & Shingon

Shugendō’s development was strongly influenced by the Kami-Buddha religious matrix of the medieval period. During the Heian era (794-1185), shrines were constructed alongside temples on many sacred mountains, epitomized by the powerful Tendai shrine-temple multiplex on Mt. Hiei 比叡 (northeast of Kyoto) and the holy places throughout the nearby Kumano mountain range. The local kami residing on these peaks were considered manifestations of the imported Buddhist divinities, and pilgrimages to these sites were believed to bring double favor from both the kami and the Buddhist deities. Shugendō beliefs were particularly affected by the Tendai 天台 school (then arguably Japan’s mainstream Buddhist sect), and by the esoteric beliefs of the Shingon 真言 sect of Buddhism. The Tendai school attempted a synthesis of various Buddhist doctrines, including faith in the Lotus Sutra, esoteric rituals, Amida (Pure Land) worship, and Zen concepts. Tendai gained great court favor, rising to eminence in the late-Heian era. Shingon was introduced to Japan around the same time as Tendai. Both schools played monumental roles in the merger of Kami-Buddha beliefs, but Shingon philosophy (predominantly esoteric, with mystical and occult doctrines and complex practices) did not enjoy the same degree of court patronage and popular appeal as Tendai.

Over time, a complex (albeit loose) web of affiliations developed among Shugendō, Tendai, and Shingon sites. These affiliations were codified by the government in the early Meiji period, with Tendai-affililiated Shugendō designated the Honzan-ha 本山派 branch and Shingon-affililiated Shugendō designated the Tōzan-ha 当山派 branch. However, says scholar Gaynor Sekimori: "Tendai-affiliated Shugendō certainly dates from medieval times, but the emergence of a conscious Tozan-ha and its identification with Shingon can really only be dated from the Edo period onward. Even scholars of Japanese religion from peripheral fields are caught out on this and make erroneous assumptions."

Seikiguchi Makiko, a scholar of the Tōzan-ha, emphasizes this point as well, claiming that the sectarian distinction between Tendai Shugendō and Shingon Shugendō that emerged in the Edo period failed to accurately reflect the situation in medieval times. That is still the case today. It is misleading, she says, to discuss the pre-Edo Tōzan-ha simply in terms of Shingon doctrine. <citation here>

Banning of Shugendō. In 1868 the Meiji government outlawed the fusion of Kami-Buddha (Shinbutsu Bunri 神仏分離) and forcibly separated Shintō and Buddhism. It 1872, the Shugendō sect was banned as a superstitious religion. Shugendō sites either became Shintō shrines (e.g. Hakusan, Mt Hiko), thus losing their Shugendō heritage, or they became branches of either Tendai or Shingon Buddhism. Mt Haguro was an exception, for it managed to retain a small Buddhist presence that successfully maintained its Shugendō traditions. But overall, a large number of practices were lost and mountain-entry rituals in particular were not kept up. Adds scholar Gaynor Sekimori: “Shugendō was banned in 1872 for its eclecticism by a reformist government anxious to be perceived as having shed the shackles of a ’feudal’ or benighted past. Shugendō priests were given the choice of becoming (Shintō) shrine priests or fully ordained priests within the tradition (Tendai or Shingon) to which their institutions had been affiliated, or giving up their religious role completely. The very small number (less then ten per cent) who joined Buddhist institutions found themselves ranked inferior to regular priests and encouraged to integrate with their new sects rather than try to maintain their Shugendō traditions. Initially they were forbidden to wear their distinctive robes, to perform Shugendō-style rituals, and to conduct Shugendō-related activities.” <citation here>

Photo by Yoshio Wada

www.wadaphoto.jp/maturi/hiwatari1.htm

Modern Shugendō. Shugendō was not allowed to exist independently thereafter until 1946, when the old legislation was rescinded. This legislative change prompted a large number of Shugendō schools / lineages / groups -- those forced to take cover within the Tendai and Shingon sects during the Meiji period -- to declare their insititutional independence from Tendai and Shingon. Some of the most important independent sects that emerged include:

- those associated with the pre-Meiji Honzan-ha (now known as Tendai Jimon-shū, Honzan Shugen-shū, and Kinbusen Shugen Honshū)

- those assocated with the Tōzan-ha (Shingon-shū Daigo-ha)

- those associated with Haguro Shugendo (Haguro Shugen Honshū)

- In the past seven decades, Shugendō practice has slowly recovered and today can be found in various localities around the nation (see Centers of Shugendō). Research on Shugendō topics by scholars in Japan and abroad has also experieced a revival.

Honzan-ha 本山派 (Tendai). The Honzan-ha was centered around Shōgo-in Temple 聖護院 (in Kyoto) from medieval times down to the end of the Edo period. Today Shōgo-in is the head temple of the Honzan Shugen-shu 本山修験宗, an independent branch of Shugendō and one of the three most important temples in the Yoshino-Ōmine area. The other two are Kinpusenji Temple 金峯山寺 and Daigoji Temple 醍醐寺 (aka Sanbōin 三宝院). Honzan Shugen-shu considers En no Gyōja to be the founder and monk Zōyo 増誉 (1032-1116)to be the restorer. It has 33 sacred pilgrimage sites in western Japan. The number 33 corresponds to 33 manifestations of Kannon Bodhisattva (a central divinity of the Lotus Sutra). The nearby Katsuragi mountain area, which is also associated with this Shugendō branch, has 28 places of pilgrimage worship -- these 28 sites correspond to the 28 chapters of the Lotus Sutra (an important text in Tendai philosophies). The Yoshino-Ōmine area is considered one of their most sacred areas.

Tōzan-ha 当山派 (Shingon). The Tōzan-ha is centered around Ozasa 小篠 (Ōminezan), Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 (in Nara), and the Sanbō-in 三宝院 (Daigoji Temple 醍醐寺 in Kyoto). Like the Honzan-ha, its members declared independent status after 1946, most notably Daigoji Temple 醍醐寺, now the head temple of the Shingon-shū Daigo-ha. The Tōzan-ha acknowledges En no Gyōja to be the father of Shugendō, but it honors the monk Shōbō 聖宝 (832-909) as the restorer. Shōbō is the acclaimed founder of Daigoji Temple. The Tōzan-ha has 36 holy places of pilgrimage in Japan’s Yoshino-Ōmine-Kinpu region. The Yoshino-Ōmine area is considered one of their most sacred areas.

Photo by Yoshio Wada

www.wadaphoto.jp/maturi/hiwatari1.htm

|

The pilgrimage to Sanjō-ga-take

is called Okugake 奥駈 or

Mineiri 峰入り. (Photo)

|

|

Centers of Shugendō Practice & Pilgrimage Centers of Shugendō Practice & Pilgrimage

Shugendō's main centers of practice and pilgrimage both in ancient times and today are:

- Ōmine 大峰山 mountain range in Nara Prefecture. The most ritually important peak is Mt. Sanjō-ga-take 山上ヶ岳. Also known as Ōminezan 大峰山, this mountain and its temple (Ōminesanji 大峰山寺), and a large area around the site, are still forbidden to women. The age-old tradition of banning women from certain holy sites was enforced widely in Japan until modern times, for women were considered disruptive to the monastic practices of male practitioners. Today Ōminesanji Temple (which is venerated by all groups associated with Ōmine Shugendō) handles a complicated management system that includes Ryusenji Temple (in Dorogawa, affiliated with the Daigo lineage of Shingon), the Yoshino temples of Tonanin and Sakuramotobo (both Kinpusen Shugen Honshū), Kizoin (Honzan), Chikurin’in (unaffiliated), Shōgo-in (Honzan’s head temple in Kyoto, Tendai related), Kinpusenji (see below) and Daigoji (Shingon). Also in the mix are representatives from the villages of Dorogawa and Yoshino, and from pilgrimage confraternities in Osaka and Sakai. This complexity, says scholar Gaynor Sekimori, “is why the plan to open Mt. Sanjō-ga-take to women in 1999 failed – too many different interests.”

- Mt. Kinpusen 金峯山 in Nara Prefecture. Mt. Kinpusen is also known as Mt. Yoshino, and is located in the Ōmine mountain range. The head temple of Mt. Kinpusen/Yoshino is Kinpusenji 金峯山寺 (see Zaōdō). Its ties with the Tendai sect of Buddhism were close in the pre-Meiji period, but now the temple complex is an independent Shugendō sect known as Kinpusen Shugen Honshū 金峯修験本宗. However, in Yoshino town (where Kinpusenji is located), there are numerous Shugendō temples, variously affiliated, which sponsor mountain entry rituals (e.g., Okugake 奥駈). These include Sakuramotobō 桜本坊 (Kinpusen Shugen Honshū), Kizoin (Honzan Shugenshu), and Tonanin (Kinpusen Shugen Honshū). The whole area from the town of Yoshino to Sanjōgatake is also called Mt Yoshino.

- Hakusan Mountains. Jump to Hakusan page.

- Dewa Sanzan. Another ancient center of Shugendō practice, pilgrimage, and lore is located on the three mountains of Dewa Sanzan 出羽三山 in central Yamagata Prefecture. The three sacred peaks are Mt. Haguro 羽黒山 (419 meters), Mt. Gassan 月山 (1980 meters), and Mt. Yudono 湯殿山 (1504 meters). See Deities of Dewa Sanzan below. Also see Quick Summary of Dewa Sanzan below.

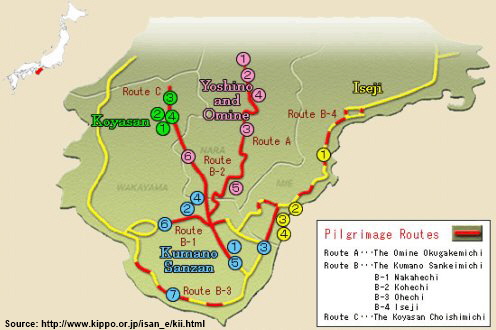

Sacred Sites & Pilgirmage Routes in the Kii Mountain Range (Japan)

The Ōmine range and Mt. Kinpusen are located in the Yoshino-Kumano National Park 吉野熊野国立公園 in Japan’s Kansai region. The park area was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2004. This area remains a popular pilgrimage site and ascetic (yamabushi 山伏) training ground. Hiking along the pilgrimage routes in this area is considered “a must” for Shugendō practitioners. Such treks are known as Okugake 奥駈 or Mineiri 峰入り. For more on Shugendō’s most important sites, please see Sites of Importance to Shugendō below.

|

Yoshino-Kumano National Park in the Kii Mountain Range. Famed for centuries for its mountains and temples and shrines (also the home of the legendary Tengu Goblin, the slayer of vanity), this region of Japan is very mountainous, with steep ridges, complicated peaks, and vast gorges. One of the most prominent religious sanctuaries since the Heian Period. The Yoshino region southeast of Osaka is the northern entrance of the Nyūbu 入峰 (mountain pilgrimage). The Ōmine mountain range between Kumano and Yoshino includes places of seclusion and ascetic practices such as Ozasa, the Shō rock carvern, the Zenki valley, and Mt. Tamaki. The pilgrimage path leads from Yoshino through Ōmine to Kumano.

Japan’s Kii Peninsula &

Route of the Famous Yoshino-Kumano Pilgrimage

Source: Shugendo and the Yoshino-Kumano Pilgrimage.

Story & Map by scholar Paul L. Swanson. Click here for citation and URL.

DEITIES OF SHUGENDŌ

The deities worshipped by Shugendō vary widely, although many commonly venerate Fudo Myō-ō, Zaō Gongen, Kujaku Myō-ō, and Kōjin-sama. Various deities in the Shugendō pantheon are discussed below.

Two Demon Attendants / Servants of Enno Gyōja

En no Gyōja (aka Uzunu) is often shown in Japanese artwork accompanied by a male demon named Sekigan 赤目 (lit. = Red Eyes; also pronounced Shakugan) and the demon’s wife Kōkō 黄口 (lit. = Yellow Eyes). There are many different legends about the two, but in all such tales, the pair eventually change their evil ways and become En no Gyōja’s servants. In one legend, Sekigan and Kōkō regret their sins, ask for Ozunu's help, and become his disciples. Says the Dungeon Website: “Ozunu (aka En no Gyōja) gave them four verses in praise of Buddha -- verses that have the power to grant salvation and to raise up an enlightened heart. By regularly reciting the verses, the two demons were able to become humans. Once this happened, the demons changed their names. Red Eyes was named Zenki 前鬼 (Front Demon) and Yellow Eyes was named Goki 後鬼 (Behind Demon). Ozunu is especially revered in the sacred Ōmine mountain range, where he forced his way deep into the interior and threw himself into 1,000 days of austere ascetic practice. Ozunu opened up the Ōmine mountain range, establishing halls of asceticism, and he made Zenki and Goki live in the interior of Yoshino's Kinpu mountains (just north of Ōmine) to protect the disciples of ascetic practice.”

Senkōji Temple 千光寺 in Nara.

Dated to Kamakura Period (13th century). Central statue 1.1 meter in height.

For more English details about this temple, click here. PHOTO Courtesy this J-Site.

〒636-0945 奈良県生駒郡平群町鳴川188, TEL: 0745-45-0652

元山上千光寺(もとさんじょうせんこうじ

En no Gyoja and Two Demon Servants - Goki and Zenki. Wood. H = 1.5 meters. Edo Period.

Treasure of Mitsumine Jinja 三峰神社. Housed at the Mitsumine-zan Hakubutsukan.

Museum 三峰山博物館 in Chichibu 秩父 (Saitama). TEL: 0494-55-0241

Photo from Mitsumine-zan Hakubutsukan; (scanned from museum catalog).

Modern Images of Zenki and Goki

Available online at Japanese Statuary Store

Zenki 前鬼 ・ Goki 後鬼 (飯野町)

www.db.fks.ed.jp/pic/30103.191/images/30103.191.00001.jpg

No date given at above web site.

- Says Dungeon Website: “As Zenki and Goki were a married couple, they were seen as the yin and the yang. The husband Zenki, as a man, represented the yang pinciple. Because the yang advances in the front, Zenki, who stood at the front, was given the kanji "front" by Ozunu. Since the yin principle was associated with being withdrawn, Ozunu gave the wife the kanji "behind," as in "close behind," for her name. True to their names, Zenki would stand in front of Ozunu and use an axe to cut a path while Goki would express obedience by following behind their master. The set of demons used by Ozunu — Zenki, Goki, and their five children — became the yin, yang, and the five elements which he made use of through magic and seals. Their human names are believed to have been Otomaru 乙丸 and Wakamaru 若丸. It is also said that Ozunu came to call them Righteous Learning and Righteous Wisdom. During the Edo era, in 1672 CE, a Buddhist priest named Sōryojōen 僧侶常円 wrote a summary of these events in Selections from the Heart of Shugen 修験心鑑鈔. The husband became associated with the Diamond Realm Mandala (which contains the gods of wisdom), and the wife became associated with the Womb Realm Mandala (which contains the gods of logic). Ozunu declared: "Zenki performs his tasks with wisdom, and Goki performs her tasks with logic."

Says Dungeon Website: “Red Demon, Blue Demon. An oft-found image of Ozunu shows the husband Zenki carrying an axe. The axe rips through the world of the disillusioned, and his left fist destroys the evil creatures. He is a red demon whose tightly closed mouth has the meaning of growling in the Diamond Realm, and his hair stands up in the shape of flames (to burn away impurities). The wife Goki carries a jar filled with Seisui 聖水 (called Akamizu 赤水 or sacred water or "Concealing Attendant Water" or "Logic/Truth Water of Great Mercy"). She bears a case filled with seeds (chestnuts?) on her back, and sometimes she is depicted holding the benevolent Awesome Healing Seal in her right hand while she holds the water jar in her left. She is a blue demon whose mouth is open in a flattering shape. Her hair is smoothed down like a veil. (Different sources give different names to Zenki and Goki. In Secret Collections of Shugen’s Main Tenets 修験修要秘決集 they are known as Chidōki (Wise Child Demon) and as Zendōki (Zen Child Demon). In the True Narrative of Enno Gyōja 役行者本記 (15th century), they are called Myōdōki (Miraculous Child Demon) and Zendōki (Virtuous Child Demon). Says Dungeon Website: “Red Demon, Blue Demon. An oft-found image of Ozunu shows the husband Zenki carrying an axe. The axe rips through the world of the disillusioned, and his left fist destroys the evil creatures. He is a red demon whose tightly closed mouth has the meaning of growling in the Diamond Realm, and his hair stands up in the shape of flames (to burn away impurities). The wife Goki carries a jar filled with Seisui 聖水 (called Akamizu 赤水 or sacred water or "Concealing Attendant Water" or "Logic/Truth Water of Great Mercy"). She bears a case filled with seeds (chestnuts?) on her back, and sometimes she is depicted holding the benevolent Awesome Healing Seal in her right hand while she holds the water jar in her left. She is a blue demon whose mouth is open in a flattering shape. Her hair is smoothed down like a veil. (Different sources give different names to Zenki and Goki. In Secret Collections of Shugen’s Main Tenets 修験修要秘決集 they are known as Chidōki (Wise Child Demon) and as Zendōki (Zen Child Demon). In the True Narrative of Enno Gyōja 役行者本記 (15th century), they are called Myōdōki (Miraculous Child Demon) and Zendōki (Virtuous Child Demon).

Deities at Mt. Kinpusen 金峯山

Mt. Kimpusen (Kinpusen), also known as Mt. Yoshino, venerates the combinatory deity Zaō Gongen 金剛蔵王権現. Legends from Mt. Kinpusen say that when En no Gyōja visited the mountain, he prayed for a tutelary deity to appear to him, one who could save all sentient beings and help him to subdue demons and evil. According to tradition, Zaō appeared in answer to his petitions, but only after other Buddhist divinities had appeared but been rejected as too meek. Mt. Kimpusen (Kinpusen), also known as Mt. Yoshino, venerates the combinatory deity Zaō Gongen 金剛蔵王権現. Legends from Mt. Kinpusen say that when En no Gyōja visited the mountain, he prayed for a tutelary deity to appear to him, one who could save all sentient beings and help him to subdue demons and evil. According to tradition, Zaō appeared in answer to his petitions, but only after other Buddhist divinities had appeared but been rejected as too meek.

In the beginning, three Buddhist divinities appeared to him: (1) Shakyamuni, the Historical Buddha, the Buddha of Past Ages; (2) 1000-Armed Kannon Bodhisattva, the God/Goddess of Compassion, the Savior in the Current Age; and (3) Miroku Bodhisattva, who is slated to become the Buddha of the Future. En no Gyōja prayed again, and the triad merged into one deity, the Avatar Zaō Gongen, who endowed En no Gyōja with magical powers. This legend and others did not appear until the 12th-13th centuries, long after the death of En no Gyōja. There are many variations. In one story, the first deity who came forth looked like the gentle Jizō Bosatsu, but was rejected as too mild in appearance. Only later, after various deities had appeared, did the fierce form of Zaō emerge and gain acceptance.

Writes Kadoya Atsushi at Kokugakuin University: "Another version relates that Zaō appeared in the form of a mandala, sitting on a jeweled stone in Lake Seiryū at the peak of Mt. Kimpu. Another states that while En was meditating at Mt. Yūjutsu, the deity Benzaiten appeared on the seventh day, becoming known as the Tenkawa Benzaiten; on the 14th day a Jizō Bodhisattva appeared, and this became known as the Shōgun Jizō (Battle Field Jizō) of Kawakami. Finally, on the 21st day Zaō Gongen appeared as the fierce deity Kōjin, incorporating the identities of Dainichi Buddha, Shakyamuni Buddha, and Amida Buddha." <end quote from Kadoya>

Zaō Gongen is perhaps the most powerful divinity of religious mountain worship (Sangaku Shūkyō 山岳宗教) in Japan. He is widely venerated in the entire mountain range stretching from Yoshino to Kumano (the cradle of Shugendō practice), but also venerated at numerous remote mountain shrines and temples throughout the country.

|

|

|

(L) Miroku (C) Historical Buddha (R) 1000-armed Kannon

Three “Hidden Buddha 秘仏” represented as Zaō Gongen

at the Zaōdō 蔵王堂 (Zaō Hall), Kinpusenji Temple 金峯山寺

Wood (cherry). Central Image About Seven (7) Meters High.

National Treasures, National Important Cultural Properties.

Dated to Azuchi-Momoyama period, though unclear.

Photo courtesy of Kinpusen Temple's web site.

|

Says the temple’s website: 秘仏本尊・金剛蔵王権現・本地仏の釈迦如来(過去世)・千手観音(現在世)・弥勒菩薩(未来世)・権化・金剛蔵王とは、金剛界と胎蔵界を統べるという意味も表しています

|

|

|

|

Deities at Dewa Sanzan 出羽三山

|

Shōken Daibosatsu

Founder of Haguro Shugendō

Treasure of Hagurosan Kōtakuji

Shōzenin (head temple)

Photo: Dr. Gaynor Sekimori

Nissei Manishu 日精摩尼手

Three-legged crow inside sun disc.

In Japan, Nikkō Bodhisattva (the Sunlight Bosatsu who serves the Medicine Buddha known as Yakushi Buddha) as well as Myōken 妙見 (the deification of the Pole Star and Big Dipper, whose name can be literally translated as "wonderous sight") are associated with the three-legged crow. Myōken is a major star deity at sacred Mt. Haguro, and possesses the power to cure eye diseases. People with eye disease or poor eye sight in Japan can purchase talismans or icons called Nissei Manishu 日精摩尼手, which show the crow inside the sun disc. Making proper pleas and prayers to the icon is said to cure one's eye problems.

Emperor Jimmu and 3-legged crow.

Artwork by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

月岡芳年 (1839-1892).

Three-Legged Black Crow

Logo of Japan Football Association

For more photos of Japan’s

three-legged black crow,

see this J-site.

|

|

According to Maison Franco-Japonaise (which translated the film Shugen: The Autumn Peak of Haguro Shugendō): “The founder of Haguro Shugendō (at Dewa Sanzan 出羽三山) is Nōjo Taishi 能除太子, who is said to have come to Haguro early in the 7th century. He was given the posthumous title of Shōken Daibosatsu 照見大菩薩 in the 19th century. Legend says he was the third son of the late 6th-century Emperor Sushun 崇峻天皇, and the cousin of the famous Shōtoku Taishi. According to folklore, prince Nōjo renounced his title and position, took the name Kōkai 弘海, and became a wandering hermit of the mountains. He is depicted as a strange being, dark of skin and with exaggerated facial features, his mouth extending from ear to ear. It was to a place called Akoya, in a narrow valley full of thick growth, with a waterfall at one end, that Nōjo Taishi was guided by a mystical three-legged crow, and it was here that he first did ascetic training. Here he also discovered a statue of Kannon Bosatsu and it was from here that he opened the three mountains (Dewa Sanzan) as a Shugendō site.” <end quote> According to Maison Franco-Japonaise (which translated the film Shugen: The Autumn Peak of Haguro Shugendō): “The founder of Haguro Shugendō (at Dewa Sanzan 出羽三山) is Nōjo Taishi 能除太子, who is said to have come to Haguro early in the 7th century. He was given the posthumous title of Shōken Daibosatsu 照見大菩薩 in the 19th century. Legend says he was the third son of the late 6th-century Emperor Sushun 崇峻天皇, and the cousin of the famous Shōtoku Taishi. According to folklore, prince Nōjo renounced his title and position, took the name Kōkai 弘海, and became a wandering hermit of the mountains. He is depicted as a strange being, dark of skin and with exaggerated facial features, his mouth extending from ear to ear. It was to a place called Akoya, in a narrow valley full of thick growth, with a waterfall at one end, that Nōjo Taishi was guided by a mystical three-legged crow, and it was here that he first did ascetic training. Here he also discovered a statue of Kannon Bosatsu and it was from here that he opened the three mountains (Dewa Sanzan) as a Shugendō site.” <end quote>

Why the three legs and why the black crow inside a sun disk? The most plausible reasons involve Chinese mythology and Japan’s own creation legends. First, a black 3-legged crow known in China as Sānzúwū 三足烏 (lit. = three-legged bird) appears in Chinese art dated to the Yǎngsháo 仰韶 period (5000-3000 BC). In Chinese mythology and ancient texts, this bird is intimately related to the sun. According to the Huáinánzǐ 淮南子(2nd century BC Chinese text), this bird has three legs because three is the emblem of Yang -- and the supreme essence of Yang is the sun.

Second, in Japan, various deities are associated with the 3-legged black crow, including Myōken (the deification of the Pole Star and Big Dipper), Nikkō Bosatsu (Sunlight Bodhisattva), and Emperor Jimmu 神武天皇 (Japan’s legendary first emperor). In Japan’s own creation myths (e.g., Nihon Shoki 日本書紀, submitted to the Japanese imperial court in 720 AD), a giant crow called Yata-garasu 八咫烏 (eight-span crow) appeared to Jimmu, who had landed on the shores of Japan but gotten lost. The crow was sent by Amaterasu Ōmikami 天照大神 (Japan’s supreme sun goddess) to lead Jimmu to Yamato (the heartland of Japan). Says site contributor Cate Kodo Juno, an ordained Buddhist priest of Japan's Shingon sect: “Since the crow is also associated with Myōken and the Pole Star, could it be that it was the Pole Star that guided Jimmu?” For those who want to read the original Nihon Shoki story in Japanese, go to this site at Berkeley.edu, select Book 3, select Jimmu Tenno, then search for term = Yata-garasu.

Third, site contributor Cate Kodo Juno offers another asute observation: “It is most likely that the story of Haguro Shugendō founder Nōjo Taishi emulates the story of Emperor Jimmu, as often happens in hagiographies, in order to provide added legitimacy and authority to Nōjo’s lineage.”

Some final words on the above Shugendō legend. Today people might equate the three-legged bird with the three sacred mountains of Dewa Sanzan, but the basis of the legend clearly goes back to earlier Chinese mythology. Also, Myōken, the deification of the Pole Star and Big Dipper, is a major star deity at sacred Mt. Haguro, one said to possess the power of curing eye diseases. Let us recall that Myōken 妙見 literally means "wonderous sight."

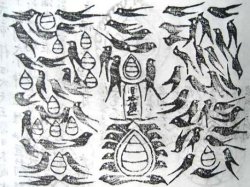

Crows also figure prominently in modern-day talismans at Kumano-based shrines. Below are two such talismans.

Kumano Go-ō-hōin 熊野牛王宝印

Kumano Kōtai Jingū 熊野皇大神宮 Crow Amulet (paper).

Photo courtesy this J-site.

Kumano Nachi Taisha Shrine 熊野那智大社 (Wakayama)

Above Photo. Crow amulet at Kumano Nachi Taisha Shrine 熊野那智大社 (Wakayama). Says Cate Kodo Juno: “The characters saying “Nachi-hoin-musubi 那智宝印結び“ are written here in the form of 72 crows. The 3-Legged Crow was considered to be the messenger of the kami of the Kumano Sanzan. This talisman signifies the binding promise made between the kami and human beings, but also between people themselves and this was used for recording formal oaths in times past. According to legend, if someone broke their promise one crow would die at the Kumano Sanzan. People buy the charms and put them in their home shrine to protect the family from evil.”

Yatagarasu in the Nihon Shoki 日本書紀

The below translation from Book Three of the Nihon Shoki (JIMMU TENNO 神武天皇) comes from the online text database of University of California Berkeley: “Then Amaterasu no Ōkami instructed the Emperor in a dream of the night, saying: ’I will now send thee the Yata-garasu, make it thy guide through the land.’ Then there did indeed appear the Yata-garasu flying down from the Void. The Emperor said: ‘The coming of this crow is in due accordance with my auspicious dream. How grand! How splendid! My Imperial ancestor, Amaterasu no Ōkami, desires therewith to assist me in creating the hereditary institution.’" <end quote>

Sanyama-sama 三山様

The three mountains of Dewa Sanzan, popularly known as Sanyama-sama 三山様, have long been revered as a dwelling place for the spirits of the dead and as the abode of various kami associated with mountains, agriculture, and fishing. The kami were regarded as manifestations of Buddhist divinities, and so were given the title Gongen (literally “manifestation” or “avatar”), as were the kami of other sacred mountains associated with Shugendō, such as Hakusan, Nikko, and Mt Hiko (see also Zaō Gongen above). Modern scholarship calls such combinatory religion Shinbutsu Shūgō 神仏習合 (literally “Kami-Buddha association”), and discusses the relationship between the kami and their Buddhist counterparts in terms of a theory called Honji Suijaku 本地垂迹, where the Buddhist divinities are regarded as the honji 本地 (original manifestation) and the kami as the suijaku 垂迹 (trace manifestation).”

The three Buddhist deities (honji 本地) of Dewa Sanzan:

- Amida Buddha (Skt. Amitābha) at Mt. Gassan, whose avatar (Jp. = Gongen) is Gassan Daigongen 月山大権現

- Dainichi Buddha (Skt. Mahāvairocana) at Mt Yudono, whose avatar is Yudonosan Daigongen 湯殿山大権現

- Shō-Kannon Bodhisattva (Skt. Avalokiteśvāra) at Mt Haguro, whose avatar is Hagurosan Daigongen 羽黒山大権現; the central deity

The three kami (suijaku 垂迹) of Dewa Sanzan:

- Tsukiyomi-no-Mikoto 月読命 for Mt. Gassan. Child of creator gods Izanagi and Izanami; revered as a deity of agriculture and protector of the food supply.

- Ōyamatsumi no Kami 大山津見神 (aka 大山祇) for Mt. Yudono. Translated as “great deity of mountain jurisdiction.” A child of Izanagi and Izanami. This kami is mentioned in both the Nihongi 日本紀 (Chronicles of Japan, written around 797 AD) and the Kojiki 古事記 (Record of Ancient Matters, released around 712 AD). Also known as Yama no Kami 山の神 (lit. mountain kami). Ōyamatsumi is worshiped by hunters, charcoal-burners, and woodcutters; a common practice is to offer this deity an ocean fish called Okoze オコゼ. Ōyamatsumi is also enshrined at Bessan Jinja 別山神社 on holy Mt. Bessan, one of the sacred Hakusan Mountains. (Note from Kokugakuin University: “The term yamatsumi means a spirit dwelling within a mountain, with the result that the name Ōyamatsumi means a great deity with jurisdiction over mountains. Shrines to kami with this name can be found throughout Japan. In Japanese folk religion, the kami of any given mountain is sometimes called Ōyamatsumi, as is the spirit of someone who has died within the mountains; in many cases, cairns of stones are erected as a place of worship.” <end Kokugakuin quote>

- Ukanomitama-no-Mikoto (Uganomitama) 宇迦之御魂神 for Mt. Haguro. This deity’s name can also be written 倉稲魂命. The kami of foodstuffs, who is most commonly known as Inari Kami, who represents the spirit of rice. Ukanomitama is also identified with Tamayorihime 玉依比売, the divine bride and fertility goddess (a female who cohabits with kami and gives birth to kami children). However, the original kami of Mt Haguro seems to have been Ideha-no-Kami 伊弖波神, the tutelary deity of the old province of Ideha (Haguro), who is sometimes identified as Tamayorihime. Nonetheless, the most general kami identification for Mt. Haguro remains Ukanomitama.

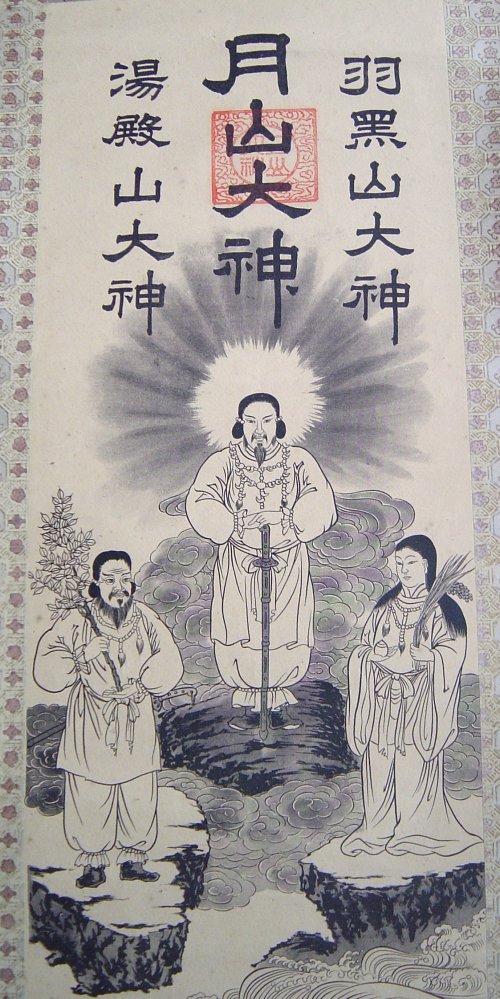

Scroll Painting; Post-Meiji Era

Shows the Three Shintō Kami of Dewa Sanzan

Photo in collection of Dr. Gaynor Sekimori

From Left to Right: Kami of Mt. Yudono, Kami of Gassan, Kami of Mt. Haguro.

The kami of Mt. Haguro appears as a feminine deity. She might be Tamayorihime 玉依比売

(the divine bride), who is also identified with Ideha-no-Kami 伊弖波神. The latter is

considered the original deity of Mt. Haguro, but is now known as Ukanomitama-no-Mikoto.

Scroll Painting; Pre-Meiji Era

Shows the Three Buddhist Deities of Dewa Sanzan

Photo in collection of Dr. Gaynor Sekimori

L to R: Deity of Haguro (Kannon), Deity of Yudono (Dainichi), Deity of Gassan (Amida)

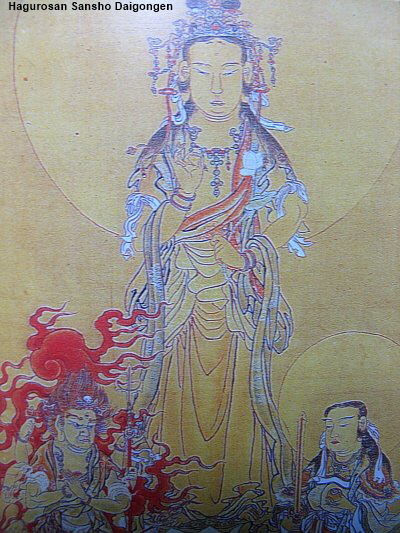

Hagurosan Sansho Daigongen. In addition to the above deities, Mt. Haguro has three divinities known as the Hagurosan Sansho Daigongen 羽黒三所権現:

- Kannon Bodhisattva. Lord of Compassion, the central divinity of Mt. Haguro.

- Myōken Bosatsu. Deification of the Pole Star and the Dipper constellation.

- Gundari Myō-ō. Deification of the Six Marker Stars of the South.

When the Meiji government forcibly separated Shintō and Buddhism (Shinbutsu Bunri 神仏分離) in 1868, it ordered a separation of Kami and Buddha worship, prohibited Kami-Buddha mixtures in temples and shrines, and banned Shugendō. After this, the kami could no longer be revered as avatars of the various Buddha and Bodhisattva. The shrine-temple complex on Mt Haguro was converted to a Shintō shrine called Ideha Jinja 伊弖波神社, and the other two mountains were designated Gassan Jinja 月山神社 and Yudonosan Jinja 湯殿山神社. Today they are collectively known as Dewa Sanzan Jinja 出羽三山神社, and the three deities are worshipped together in the main hall (Gassaiden 合祭殿) on Mt. Haguro.

Hagurosan Sansho Daigongen (photo from Haguro Exhibition)

Kannon in center, Gundari engulfed in flames, Myōken at lower right

Date: Need to confirm

Legend & Lore Related to Enno Gyōja 役行者

-

Treasure of Umanotera Temple 馬の寺

(Official name Ishibaji Temple 石馬寺)

Shiga Prefecture. Wood. Important Cultural Treasure, Kamakura Period

Photo courtesy this J-site.

Statue accompanied by two demon

attendants (not shown in above photo) |

|

Honorary Title. In the year 1799 of the Edo era (1615–1868), the honorary title of Shinben Daibosatsu 神辺大菩薩 (also read Jinben Daibosatsu; means Miraculous Great Bodhisattva) was bestowed upon En no Gyōja by Emperor Kōkaku 光格天皇 (1771-1840). Honorary Title. In the year 1799 of the Edo era (1615–1868), the honorary title of Shinben Daibosatsu 神辺大菩薩 (also read Jinben Daibosatsu; means Miraculous Great Bodhisattva) was bestowed upon En no Gyōja by Emperor Kōkaku 光格天皇 (1771-1840).

- Honorary Title. UNCONFIRMED. In the Edo era (1615–1868), Ozunu was written of as the "Law Awakening Bodhisattva" in the Shugen Pentateuch 修験五書 (Shugen Gosho).

- Mt. Minō, Ryūanji Temple

& Maple Leaf Tempura

Says site contributor Gabi Greve: “More than 1,300 years ago, the famous ascetic En no Gyōja 役行者 was practicing austerities at Mt. Minō 箕面山 (near Osaka). He was enchanted by the red leaves of the maple trees near the Minō Waterfall (Minō no Taki 箕面の滝) and fried them in the rapeseed oil of his lamp. In memory of this scene, locals today make a sweet tempura using maple leaves and give this tasty treat to visitors. This local delicacy is called Momiji Tempura もみじ天ぷら or 紅葉の天ぷら.” <End quote. Learn more about this tempura treat at Gabi’s site>

Gabi continues: “Legend states that Minōyama Ryūanji Temple 箕面山瀧安寺 (or “Mt. Minō Dragon Peace Temple”) on Mt. Minō was founded by En no Gyōja. Today the temple and mountain area are still important places of ascetic practice for Shugendō devotees. The waterfall (Minō no Taki) is especially famous in autumn owing to over 5,000 red maple trees growing in the area. According to legend, when En no Gyōja was practicing austerities at Mt. Katsuragi, he had a vision of ‘a mountain sending out light’ in the north. He went searching for it and found the impressive Minō waterfall, which was radiating light. He entered the cave behind the waterfall, and discovered Ryūju Bosatsu 竜樹菩薩 (lit. Dragon Shade Bodhisattva), who taught him the great laws and opened the way to enlightenment for En. Ryūju Bosatsu was originally a holy man of southern India who lived in the 2nd century AD. Since he could no longer be alive, the idea arose that the waterfall embodied the spirit of a Ryū 竜 (dragon). En no Gyōja build a temple at the location devoted to Benzaiten 弁財天 (the Buddhist-Shintō deity of water, the dragon is the protector of Buddhism and the lord of tempests and rain). He practiced for a long time in the area and thereafter attained supernatural powers.” See Gabi’s story.

Says scholar Bernhard Scheid: "In the Nihon Ryōiki 日本霊異記 (compiled around +822), one story (vol. 1/28) reports that the monk Dōshō 道昭 (629-700) on his trip to China was requested by 500 'tigers' 虎 from Silla to lecture on the Lotus Sutra, which he does only to find a Japanese among the crowd -- the saint En no Gyōja (E no Ubasoku). According to the Ryōiki, the event takes place after the year 701 which is slightly anachronistic since Dōshō is known to have lived from 629-700. Nevertheless the fact that a monk preaches to wild beasts is somewhat untypical for the quite 'realistic' style of the Ryōiki. My question is therefore whether 'tigers' could be something like a nickname, for instance for people from (former) Silla." <end Scheid quote from PMJS list> A similar story appears in the Heian-era Konjaku Monogatari (translated by Marian Ury). Click here for reference.

Reference: Ury, Marian. Tales of Times Now Past. Sixty-Two Stories from a Medieval Japanese Collection. University of California Press, 1979. See pages 84-86. Purchase book here.

Marian Ury was a professor of comparative literature at the University of California, Davis. She specialized in medieval Japanese literature. She died of cancer on 25 April 1995 at the age of 62.

HOW THE VENERABLE DOSHO WENT TO CHINA, WAS TRANSMITTED THE HOSSO TEACHINGS, AND RETURNED HOME. PP. 84-86. From Chapter 11, Story Four, in the Konjaku Monogatari. Translated by Marian Ury.

- From Japan's mid-Heian period, Zaō Gongen was also considered a manifestation of Miroku Bosatsu 弥勒. Says JAANUS: "In the mid-Heian period, when the cult of Miroku 弥勒 grew popular, Kimpusen came to be known as the inner sanctum of Miroku's paradise, Tosotsu Naiin 兜率内院, and Zaō Gongen was considered a manifestation of Miroku. Zaō Gongen was the guardian of Mt. Kimpusen, lit. "Gold Mountain," which was believed to contain gold treasure that would become accessible when Miroku appeared on earth. This was a major site of sutra burials, a practice said to have been introduced from China by the monk Ennin 円仁 in the 9th century. Copies of sutras were buried along with the donor's instructions for their future benefits. The sutras were expected to rise and bear witness to the religious devotion of the donor. The cult of Zaō Gongen was carried throughout Japan along with the practices of mountain religion and there are many images of him, including small metal sculptures buried with sutras. The earliest dated image, 1001, is an engraved mirror owned by Sōjiji Temple 総持寺, Nishiaraidaishi 西新井大師, Tokyo. <source JAANUS>

- The whole mountain range from Yoshino to Kumano, the cradle of Shugendō, is considered the dual mandala of the Kongokai (Diamond Realm) and Taizokai (Matrix Realm). Kongokai represents the wisdom and efforts of Dainichi Buddha to destroy all illusion, while Taizokai symbolizes Dainichi's teachings. These two diagrammatic schemes of the cosmos are central to esoteric Buddhism. Zaō Gongen is said to encompass both realms. <above paraphrased from Songs to Make the Dust Dance, The Ryojin Hisho of Twelfth-Century Japan, a wonderful study by Yung-Hee Kim that was released in 1994.

Sites of Importance to Shugendō

SAYS JAANUS ABOUT EN NO GYŌJA:

|

Modern Painting

|

|

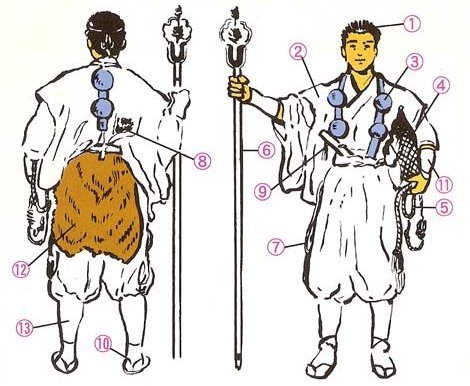

“A semi-legendary holy man noted for his practice of mountain asceticism during the second half of the 7th century. Typically he is represented wearing a white hooded robe and a pair of clogs, which have one support instead of the usual two. He holds a staff and Buddhist prayer beads in his hands and is usually seated on a rock base accompanied by two demons (oni 鬼). En no Gyōja was known as a diviner at Mt. Katsuragi 葛木 on the border of Nara and Osaka. Mentioned in early Japanese texts, the NIHON RYOUIKI 日本霊異記, and the SHOKUNIHONGI 続日本紀 as having magical powers that enable him to cast spells, he is also said to have had two demon attendants who gathered water and firewood for him. In 699 he was accused of misleading the people and expelled to Izu 伊豆. “A semi-legendary holy man noted for his practice of mountain asceticism during the second half of the 7th century. Typically he is represented wearing a white hooded robe and a pair of clogs, which have one support instead of the usual two. He holds a staff and Buddhist prayer beads in his hands and is usually seated on a rock base accompanied by two demons (oni 鬼). En no Gyōja was known as a diviner at Mt. Katsuragi 葛木 on the border of Nara and Osaka. Mentioned in early Japanese texts, the NIHON RYOUIKI 日本霊異記, and the SHOKUNIHONGI 続日本紀 as having magical powers that enable him to cast spells, he is also said to have had two demon attendants who gathered water and firewood for him. In 699 he was accused of misleading the people and expelled to Izu 伊豆.

Though his life story is riddled with folklore, he is idealized as the founder of Shugendō 修験道, a syncretic religious order which combined elements of ancient pre-Buddhist worship of mountains (Sangaku Shinkō 山岳信仰) with the doctrine and ritual of esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō 密教). It is believed that he climbed and consecrated many mountains, making sanctuaries in such places as Mt. Kinbu (Kinpu) 金峯 and Ōmine 大峰 in Nara. He was given the posthumous name of Shinben Daibosatu 神辺大菩薩 (Miraculous Great Bodhisattva). Artwork depicting En no Gyōja dates from the Kamakura period or later and is often found in temples of the Shingon 真言 sect, strongly influenced by Mt. Ōmine mountain asceticism. <end JAANUS quote>

SAYS HENRI L. JOLY ABOUT EN NO SHOKAKU (aka EN NO GYŌJA):

“One of the earliest Buddhist Prophets of Japan living in the sevent century, and who ascended several of the highest mountains, Hakusan, Tateyama, Daisen, etc., to consecrate them to Buddha. During his climbing expeditions, Enno Shokaku was accompanied by two demons, Goki 後鬼 and Zenki 前鬼, whom he had made his servants. Both were endowed with great magical powers, and they built, under their master's direction, several bridges over mountain chasms and torrents. The popular name of Shokaku is Yenno Guioja. His supernatural powers were objected to, and he died in exile at Oshima. He is depicted in an okimono preserved at the Musee Guimet, amongst the patriarchs of the Shingon sect of Japanese Buddhism.” <end quote from Henri L. Joly in his 1908 book entitled Legend in Japanese Art>

Suigyō 水行 -- Water Purification Ceremony

Photo Yoshio Wada wadaphoto.jp

RESOURCES RESOURCES

This page relies heavily on the research and help of Dr. Gaynor Sekimori of the Centre for the Study of Japanese Religions, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. She is also a visiting professor at Kokugakuin University (Tokyo, Japan). She has authored and translated numerous books and articles on Japan’s religious traditions, with a special focus on Japan’s Shugendō mountain cult.

Articles by Gaynor Sekimori:

- Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 2005, 32/2 (pp. 197–234). Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture. Paper Fowl and Wooden Fish: The Separation of Kami and Buddha Worship in Haguro Shugendō, 1869–1875. Article by Dr. Gaynor Sekimori of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London.

- Shugendo: Japanese Mountain Religion – State of the Field and Bibliographic Review. Jan. 2009. Article by Dr. Gaynor Sekimori of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London.

- Shugendo: The State of the Field. Monument Nipponica 57 : 2 (Summer 2002): pp. 207-27. Article by Dr. Gaynor Sekimori of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London.

- The Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice. Special Double Issue of CULTURE AND COSMOS: A Journal of the History of Astrology and Cultural Astronomy, Vol. 10 No 1 and 2,

Spring/Summer and Autumn/Winter 2006. Includes story Star Rituals and Nikko Shugendō by Gaynor Sekimori.

- A History of Japanese Religion, by Kazuo Kasahara. Kosei Publishing Company, 2002.

Translated by Paul McCarthy and Gaynor Sekimori. 648 pages.

- Other Articles and Activities of Dr. Gaynor Sekimori || Also see GoodReads site for more

Other Shugendō Resources:

-

En no Gyōja is mentioned in old Japanese texts like the Shoku Nihongi 続日本紀 (compiled around +797), the Nihon Ryōiki 日本霊異記 (compiled around +822), the Konjaku Monogatari 今昔物語 (late Heian period), the Fusō Ryakki 扶桑略記 (compiled around 1094), and the Enno Gyōja Hongi 役行者本記. The latter, complied around the 15th century, lists many mountain sites around Japan that were supposedly visited by En no Gyōja. En no Gyōja is mentioned in old Japanese texts like the Shoku Nihongi 続日本紀 (compiled around +797), the Nihon Ryōiki 日本霊異記 (compiled around +822), the Konjaku Monogatari 今昔物語 (late Heian period), the Fusō Ryakki 扶桑略記 (compiled around 1094), and the Enno Gyōja Hongi 役行者本記. The latter, complied around the 15th century, lists many mountain sites around Japan that were supposedly visited by En no Gyōja.

- Selections from the Heart of Shugendō 修験心鑑鈔 (Shugenshin Kanshō); written in 1672 by Buddhist priest Sōryojōen 僧侶常円; other names 修要抄, 修験修要秘決集, 修験抄, 修験柱源神法

- Secret Collection of Shugendō’s Main Tenets 修験修要秘決集 (Shugenshuyō Hiketsu Shu)

- The Hora ホラ (Conch Trumpet) of Japan. Story by Hajime Fukui. www.jstor.org/pss/842662

The conch-shell trumpet is closely associated with Shugendō practices.

- The Mandala of the Mountain: Shugendo and Folk Religion. Author Miyake Hitoshi, Editor Gaynor Sekimori. March 25, 2005. Keio University Press. URL keio-up.co.jp/kup/eng/philo/11280.html

- Sutra on the Unlimited Life of the Threefold Body. Shugendō text of dubious origin.

For English translations, see:

arvigarus.bravehost.com/history_003.htm

healing-touch.co.uk/shugendo.htm

- Legend in Japanese Art (1908)

Author: Joly, Henri L; Publisher: London ; New York : John Lane, The Bodley Head

Buy Book at Amazon | Online (Text or PDF Format) | Online (Book Flip View)

- Shugendo and the Yoshino-Kumano Pilgrimage: An Example of Mountain Pilgrimage

Author: Paul L. Swanson. Source: Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Spring 1981), pp. 55-84. Published by: Sophia University. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2384087

- Sanbōin Monzeki and the Formation of Tōzan-ha. By Sekiguchi Makiko. Paper presented at a Symposium, “Shugendō: the History and Culture of a Japanese Religion,” organised by the Columbia Center for Japanese Religion, New York, April 25-27, 2008.

- Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. June-September 1989 Issue, 16/2–3

INTRO. Shugendo & Mountain Religion in Japan. By Royall Tyler & Paul L. Swanson.

Religious Rituals in Shugendo: A Summary. By Miyake Hitoshi.

Shugendo Lore. By Gorai Shigeru.

Kōfuku-ji and Shugendo. By Royall Tyler.

The Hashira-Matsu and Shugendo. By Wakamori Tarō.

Shugendo Art. By Sawa Ryūken.

Mount Fuji and Shugendo. By H. Byron Earhart.

Honji Suijaku Faith. By Susan Tyler.

Marathon Monks of Mount Hiei. By Robert Rhodes.

- Shugendō: The History and Culture of a Japanese Religion. Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie, 18 (2009). Guest editors: Bernard Faure, Max D. Moerman, Gaynor Sekimori. Click here to purchase.

- Carter, Caleb Swift, 2014 Dissertation, UCLA, Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries. Click here to read the disseration, which focuses on the deveolpment of the Shugendō tradition at Mt. Togakushi.

Learn More at These Outside Web Pages

Films

RESOURCES IN NEED OF CHECKING

Many of the below links are outdated or no longer online. Below list courtesy Dungeon website.

- "Bukkyou Yougo no Kaisetsu." Trans. Taisa M. T. Tabi no Michishirube. 2001. Hida Kankou Co., Ltd. 11 Mar. 2003 <http://village.infoweb.ne.jp/~hidakk/bukkyou_yougo.html>.

- "Enno Gyouja." Trans. Taisa M. T. Sannensei Sentaku Jugyou Shakaika: Kyoudo no Bunkazai to Rekishi. Ikoma Minami Chuugakkou. 12 Mar. 2003 <http://www1.kcn.ne.jp/school/minami-j/sentaku02/maehara.htm>.

- Kanatani, Nobuyuki. "Enno Gyouja." Trans. Taisa M. T. Kitakawachi Kodai Jinbutsu Shi. 10 Jun. 2001. Nobk's Home-Page. 12 Mar. 2003 <http://www.infonet.co.jp/nobk/kwch/enno.htm>.

- Kasahara, Kazuo. A History of Japanese Religion. Tokyo: Kosei Publishing Co., 2001.

- "Kodai wo Kakenuketa Suupaahiiroo: Enno Gyouja." Trans. Taisa M. T. K's Plaza. Kinki Nippon Railway Co., Ltd. 11 Mar. 2003 <http://www.kintetsu.co.jp/senden/Database/E-Htm/EE0001.html>.

- "Mutou 8." Trans. Taisa M. T. Yuuran Wakusei. 11 Mar. 2003 <http://ho-ho-ho-.hp.infoseek.co.jp/mutou004.html>.

- Nao. "Enno Ozunu to Katsuragi-san." Trans. Taisa M. T. Rekishi Sougou. Nao-san no "Chuuou Kouzou Sen to Kodaishi wo Kangaeru". 12 Mar. 2003 <http://www.geocities.co.jp/Technopolis-Mars/5442/ennnoozunu.html>.

- "Shugendou: Enno Gyouja no Shougai." Trans. Taisa M. T. Shugendou. 2002. Miidera (Onjoji). 12 Mar. 2003 <http://www.shiga-miidera.or.jp/doctrine/syugendo/enno.htm>.

- "Yoshino Zaou Gongen." Trans. Taisa M. T. Hotoke-sama ni Shurui. Sora Tobu Ofudou-sama: Flying Deity Tobifudo. 12 Mar. 2003 <http://www.tctv.ne.jp/tobifudo/butuzo/1404/zaogon.html>.

- "Yougo Setsumei: Chimei." Trans. Taisa M. T. Karasu. 16 Oct. 2001. Blood gets in your eyes. 11 Mar. 2003 <http://www18.u-page.so-net.ne.jp/rd5/minato/k_yougo2.htm>.

- "Yougo Setsumei: Meishou nado." Trans. Taisa M. T. Karasu. 16 Oct. 2001. Blood gets in your eyes. 11 Mar. 2003 <http://www18.u-page.so-net.ne.jp/rd5/minato/k_yougo1.htm>.

First Published = 17 April 2009

Update = 8 April 2011 (added translation by Marian Ury, photos, spellings)

Update = 26 Jan. 2014 (added web sites by Sylvain Guintard)

Update = 23 May 2015 (added dissertation <2014, UCLA> by Caleb Swift Carter)

Click here to read dissertation.

|

|