|

|

|

|

WHO’S WHO, WHAT’S WHAT

CLASSIFYING JAPAN’S BUDDHIST DEITIES

Standard Classification in Japan

Most Deities Originated in India

|

|

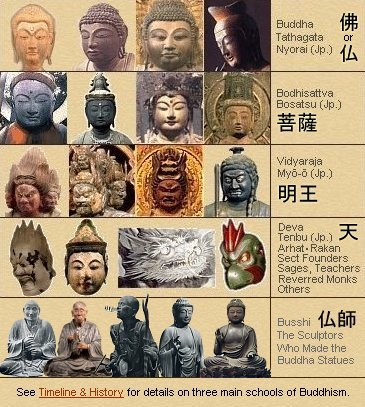

CLASSIFICATION. Buddhist deities are traditionally classified by Japanese art scholars into four main categories, and the same scheme is used at this web site (see above chart). There are other deities and groupings that don’t fit easily into any category. They are listed below in a fifth category called “Others.” In Buddhist circles, there are Ten Worlds or Ten Levels of Existence (see list below). This web site is devoted primarily to artwork of deities populating the top five levels.

Most artwork featured at this site dates from the 8th to 14th century AD, but modern-day practices and sculpture are covered as well. Nearly all listed deities originated in India, where Buddhism was born around 500 BC. Buddhism in Asia arrived last in Japan, crossing the sea from Korea and China in the early 6th century AD (see Early Japanese Buddhism for details). The Mahayana form in particular spread throughout the Japanese islands, thus the majority of surviving Buddhist sculpture in Japan today belongs to the Mahayana tradition. Artwork belonging to the Theravada and Vajrayana (Esoteric) traditions is less prominent, but it is nonetheless plentiful. Sects from all three schools are still active in Japan, but Mahayana Buddhism remains the most popular form. For a guide to the teachings of the Historical Buddha, click here.

Shintō kami (deities) feature much less prominently than Buddhist deities in Japanese artwork and religious statuary. Shintō artwork is most often found in the combinatory Kami-Buddha art of the Shugendō mountain cults, and in the scroll paintings and mandala of Tendai Shintō and Shingon Shintō. There are a number of reasons for the lack of a vigorous Shintō artistic tradition. First, Shintō existed centuries before the arrival of Buddhism to Japan in the form of shamanism, nature worship, and mountain cults. But Shintō had no written tradition and no centralized doctrine until the emergence of Ise Shintō 伊勢神道, Ryōbu Shintō 両部神道 and Tendai Shintō 天台神道 in Japan's medieval period. It is only after the 13th century that one can speak with validity of a Shintō traditiion. Second, Shintō deities were not given anthropomorphic characteristics until the 8th century, long after the arrival of Buddhism to Japan. Says JAANUS: "The first instance of making a kami image is believed to be that recorded in Tado Jingūji Garan Engi Shizaichō 多度神宮寺伽藍縁起資財帳 (Record of Properties of the Associated Temple of Tado Shrine), compiled in 801, which relates the story of how priest Mangan 満願 converted the kami of Tado to Buddhism in 763 and his subsequent portrayal of the kami in a sculpture. Thus, this artistic development appears to have occured well after the introduction of Buddhism to Japan in the mid-6th century." The sculptural legacy and artistic output of Shintō has always paled in comparison to the Buddhist camp, and the Shintō art that survives today is predominantly representative of the Kami-Buddhist matrix that existed for centuries before Japan’s Meiji government (1868-1912) forcibly separated the two religions and declared Shintō to be the main indigenous tradition.

|

|

|

|

BUDDHA

BUDDHA 佛 or 仏, TATHAGATA or NYORAI 如来. Buddha is not a personal name, but a Sanskrit term of praise, like messiah or christ, the anointed one. Another common Sanskrit term for Buddha is Tathagata. In Japan, Tathagata is rendered as Nyorai, an honorific title given to those who have attained enlightenment. This latter term is translated as "thus come" or "thus gone" or “coming from the origin" or "returning to the origin." There are many Buddha in Mahayana traditions, and Mahayana Buddhism is the main form practiced in Japan. The Historical Buddha (Shaka Nyorai; lived around 500 BC) is one of the most widely recognized Buddha in Asia and worldwide.

Nyorai

Japanese reading

For other terms of importance, including the ten honorific titles for Buddha, please see Terminology.

Statues of the various Buddha share common attributes. First, Buddha statues are generally simple, without jewelry or ornamentation. In contrast, artwork of the Bosatsu (Bodhisattva; see below) typically includes jewelry, princely clothes, and elaborate headdresses. Second, most Buddha statues are depicted with elongated ears (all-hearing), a bump atop the head (all-knowing), and a boss in the forehead (all-seeing). Third, Buddha statues are portrayed with characteristic hand gestures (mudra). There are exceptions, mind you. The Historical Buddha, for example, is sometimes shown with an ornate head piece, and images of Dainichi Buddha often show the deity wearing a crown and jewels.

Sanzebutsu 三世仏, Buddha of the Three Worlds

- Past (Amida Nyorai)

- Present (Shaka Nyorai)

- Future (Miroku Nyorai)

NOTE: Jizo Bosatsu promised to remain in this world until the advent of Miroku Nyorai. For more about the Buddha of the past, click here.

|

Fear Not Mudra. Right hand points upward. Said to be the gesture of Shaka Nyorai (Historical Buddha) immediately after attaining enlightenment. Fear Not Mudra. Right hand points upward. Said to be the gesture of Shaka Nyorai (Historical Buddha) immediately after attaining enlightenment.

Blessing Mudra. Represents the granting of wishes to those who welcome the teachings of Buddhism; right hand points downward. Blessing Mudra. Represents the granting of wishes to those who welcome the teachings of Buddhism; right hand points downward.

|

|

BODHISATTVA

BODHISATTVA 菩薩 (pronounced BOSATSU in Japan). Literally one who seeks enlightenment, those who have reached the final stage of transmigration and enlightenment, just prior to becoming a Buddha. Bosatsu will certainly attain Buddhahood, but for a time, they renounce the blissful state of Nirvana (freedom from suffering), vowing to remain on earth in various guises (reincarnations) to help all living beings achieve salvation.

The term has other meanings, but the above Mahayana concept is the most widely known. See Bosatsu Intro Page for other definitions. In Theravada Buddhism, those who have attained the final stage of transmigration and enlightenment are called the Arhat (Rakan). But to those who follow Mahayana traditions, the Arhat is below the Bodhisattva (Bosatsu) in the chain of enlightenment.

Bosatsu

Japanese reading

Statues of the Bosatsu are generally ornate. They are often shown wearing jewelry and princely clothes -- as many as thirteen ornaments (e.g., crowns, earrings, necklaces, armlets, bracelets, and anklets). The Bosatsu can sometimes be recognized by the objects they carry and the creatures they ride. There are exceptions, mind you. Jizo Bosatsu, for example, is nearly always depicted wearing a simple monk's robe. Bosatsu (Bodhisattva) generally share only one of the 32 physical attributes of the Nyorai (Buddha) -- the elongated earlobes (all-hearing). Also, the Bosatsu often wear a crown bearing an effigy of their “spiritual father,” which means one of the Five Tathagata.

|

|

|

MYŌ-Ō (Myo-o)

Jp. = Myō-ō 明王, Skt. = Vidyaraja.

Translated as the Wisdom Kings, Mantra Kings, Knowledge Kings, or Kings of Light. Introduced to Japan in 9th century.

Myō-ō (Japanese reading)

Originally Hindu deities who were adopted into the pantheon of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism to vanquish blind craving. They serve and protect the Nyorai, especially Dainichi Nyorai. Mostly worshipped by the Shingon Sect of Esoteric Buddhism.

In contrast to the saintly images of the Nyorai (Buddha) and Bosatsu (Bodhisattva), images of the Myō-ō are ferocious and menacing, for their threatening postures and facial expressions are designed to subdue evil spirits and convert nonbelievers. They are often depicted with multiple arms and heads, engulfed in flame, and carrying weapons to subdue evil.

Among this group of warlike deities, Fudō Myō-ō is the most widely venerated in Japan, and the chief of all the others.

|

|

|

TENBU (DEVA)

Jp. = Tenbu 天部, Sanskrit = Deva. Hindu deities and non-human entities that converted to Buddhism by learning the teachings of the Historical Buddha. Like the Myō-ō (see above), they stand guard over the Nyorai (see above) and Bosatsu (see above). The Sanskrit term “DEVA” is translated as “ten” in Japan, meaning “Celestial Beings.”

The Tenbu grouping includes the Deva and many other divine beings, including celestial musicians and maidens and creatures like the Dragon, the bird-man Karura, and the elephant-headed Kankiten. Most originated in ancient Indian myths, but once incorporated into Buddhism, they became protectors of the Buddhist Law (“dharma” in Sanskrit).

Tenbu (Japanese reading)

Visit the Tenbu Intro Page for

a listing of 80+ Tenbu deities.

Celestial Beings (Deva) appear in great number in mandala artwork. They live for countless ages, but even they grow old and die, for they are still trapped in the Six States of Existence, the cycle of suffering, the cycle of rebirth and redeath (i.e., Sanskrit samsara). The Deva are hindered by their great bliss and thus they fail to recognize the truth of suffering. They ultimately “use up” their good karma after countless years in paradise and once again fall down into a lower state. Says author Karen Armstrong in The Case for God (p. 12): “The Aryans called their gods ‘the shining ones’ (deva) because Spirit shone through them more brightly than through mortal creatures, but these gods had no control over the world; they were not omniscient and were obliged, like everything else, to submit to the transcendent order that kept everything in existence, set the stars on their course, made the seasons follow each other, and compelled the seas to remain within bounds.” <end quote> Celestial Beings (Deva) appear in great number in mandala artwork. They live for countless ages, but even they grow old and die, for they are still trapped in the Six States of Existence, the cycle of suffering, the cycle of rebirth and redeath (i.e., Sanskrit samsara). The Deva are hindered by their great bliss and thus they fail to recognize the truth of suffering. They ultimately “use up” their good karma after countless years in paradise and once again fall down into a lower state. Says author Karen Armstrong in The Case for God (p. 12): “The Aryans called their gods ‘the shining ones’ (deva) because Spirit shone through them more brightly than through mortal creatures, but these gods had no control over the world; they were not omniscient and were obliged, like everything else, to submit to the transcendent order that kept everything in existence, set the stars on their course, made the seasons follow each other, and compelled the seas to remain within bounds.” <end quote>

|

|

|

OTHERS. Includes traditional deities, plus sect founders, sages, teachers, reverred monks, and others. Many were deified after their death. Under development.

|

Seven Lucky Gods

10 Kings of Hell

Kami-Buddha Combinations

|

|

SCHOOLS & SECTS

PEOPLE & PRIESTS

DEVILS & DEMONS

Under development.

|

Three Main Schools

Mandala Artwork

Sects , Schools, Monks, Nuns

Oni, Demons, Devils

Sutras and Tantras

|

|

|

|

Six States of Karmic Rebirth Six States of Karmic Rebirth

The Concept of Transmigration / Reincarnation

Known in Japan as Rokudō 六道, or Rokudō-rinne 六道輪廻, or Mutsu no Sekai 六つの世界. All sentient beings are trapped in the cycle of suffering (Sanskrit = samsara), the cycle of death and rebirth, unless they can break free by achieving enlightenment. There are six states in the cycle. The lowest three states are called the three evil paths, or three bad states. They are (1) people in hells; (2) hungry ghosts; (3) animals. The higher three states are (4) Asuras; (5) Humans; (6) Devas. Upon death, all beings in the Six Realms are reborn into a lower or a higher realm depending on their actions while still alive. Among the six, only humans can attain enlightenment, for the Deva -- who are allotted a very long, happy life as a reward for previous good deeds -- are hindered by their great happiness and thus they fail to recognize the truth of suffering. The Deva ultimately “use up” their good karma after countless years in paradise and once again fall down into a lower state. To escape from the cycle, one must either (A) achieve Buddhahood in one's life, or (B) be reborn in Amida Nyorai’s Western Pure Land, practice there, and achive enlightenment there. The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen (ISBN 0-87773-520-4) has this to say about these realms of existence:

“Between the various forms of existence there is no essential difference, only a karmic difference of degree. In none of them is life without limits. However, it is only as a human that one can attain enlightenment. For this reason Buddhism esteems the human mode of existence more highly than that of the gods.”

Six States of Existence (Transmigration / Reincarnation)

- Beings in Hell. (Naraka-gati in Sanskrit, Jigokudō 地獄道 in Japanese)

The lowest and worst realm, wracked by torture and characterized by aggression.

- Hungry Ghosts. (Preta-gati in Sanskrit, Gakidō 餓鬼道 in Japanese)

The realm of hungry spirits; characterized by great craving and eternal starvation.

- Animals. (Tiryagyoni-gati in Sanskrit, Chikushōdō 畜生道 in Japanese)

The realm of animals and livestock, characterized by stupidity and servitude.

- Ashura. (Asura-gati in Sanskrit, Ashuradō 阿修羅道 in Japanese)

The realm of anger, jealousy, and constant war; the Asura (Ashura) are demigods, semi-blessed beings; they are powerful, fierce and quarrelsome; like humans, they are partly good and partly evil.

- Humans. (Manusya-gati in Sanskrit, Nindō 人道 in Japanese)

The realm of humans; beings who are both good and evil; enlightenment is within their grasp, yet most are blinded and consumed by their desires.

- Deva (Deva-gati in Sanskrit, Tendō 天道 in Japanese)

The realm of heavenly beings filled with pleasure; the deva hold godlike powers; some reign over celestial kingdoms; most live in delightful happiness and splendor; they live for countless ages, but even the Deva belong to the world of suffering (samsara) -- happiness constitutes the primary hindrance on their path to liberation, for it blinds them to the truth of suffering -- and thus even the Deva grow old, die, and are then reborn, typically in a lower realm.

Technically speaking, the road from hell to Buddhahood covers ten stages (the so-called Ten Worlds), not six.

TEN WORLDS OF EXISTENCE

The “Ten Realms” (Jp: Jikkai 十界)

- Hells (Skt: Naraka, Jp: Jigoku 地獄 -- the lowest level)

- Hungry Ghosts (Skt: Preta, Jp: Gaki 餓鬼)

- Animals (Skt: Tiryasyoni, Jp: Chikushō 畜生)

- Bellicose Demons (Skt: Asura, Jp: Ashura 阿修羅)

- Humans (Skt: Manusya, Jp: Ningen 人間)

- Heavenly Beings (Skt: Deva, Jp: Ten 天)

- Sravaka Arhats (Jp: Shōmon 声聞); listeners of Buddhist teachings

- Pratyeka Buddhas (Jp: Engaku 縁覚); self-enlightened beings

- Bodhisattvas (Jp: Bosatsu 菩薩); the compassionate ones

- Buddhas (Jp: Nyorai, Tathagata, Hotoke 仏 -- highest level)

TEN WORLDS MAY ALSO BE WRITTEN AS:

- Hell (Beings in Hell -- the lowest level)

- Hunger (Hungry Ghosts)

- Animality (Animals)

- Anger (Ashura)

- Tranquility (Humans)

- Rapture (Deva)

- Learning (Theravada Traditions, Arhat)

- Realization (Theravada Traditions, Arhat)

- Bodhisattva (Mahayana Traditions, Bosatsu)

- Buddha (Nyorai, Tathagata, Hotoke -- highest level)

The "Ten Realms" are divided into two groups. The first group (1 to 6) comprises the Six Paths of Suffering (also called the Wheel of Life in Tibet). The second group (7 to 10) comprises the four realms of enlightened existence, the “Four Noble Worlds.” For many more details, click here.

SANZEBUTSU 三世仏

Buddhas of the Three Ages (Three Kalpa)

Buddhas of the Past, Present, and Future

Skt. = Kalpa means aeon or age or era or cycle

Sanze Jippou Shobutsu 三世十方諸仏

Buddhas of the Three Ages & Ten Directions

According to Mahayana traditions, there are countless Buddhas who exist in countless world-systems, each with its own Buddha. In Japan, these Buddhas are collectively known as the Sanze Jippou Shobutsu 三世十方諸仏, which literally means "Buddhas of the Three Ages (past, present and future) and Ten Directions (four cardinal points, four intermediate directions, zenith and nadir). The three kalpa ages, written in Chinese and Japanese, are the past (莊嚴), the present (賢), and the future (星宿). There is also a much larger grouping called Sanze Sanzen Butsu (三世三千佛), which literally means "three thousand Buddhas from the three kalpas," or alternatively, the "thousand Buddhas in each of the three kalpas of the past, the present, and the future."

Kako Shichibutsu 過去七仏

Seven Buddhas of the Past

The current Buddhist era is called the "Auspicious Aeon" (Jp = Kengou 賢劫; Skt = Bhadra-kalpa). According to Buddhist lore, there are six Buddhas who came prior to Shaka (the Historical Buddha), three from the prior kalpa (Jp = Shougun 莊嚴) and three in the current era (Jp = Kengou 賢劫). This group of seven is collectively known as the "Seven Buddhas of the Past." In Sanskrit, their names are:

- Vipasyin (past kalpa)

- Sikhin (past kalpa)

- Visvabhu (past kalpa)

- Krakucchanda (present cycle)

- Kanakamuni (present cycle)

- Kasyapa (Kassapa, Kashapa) (present cycle)

- Sakyamuni (present cycle)

Shibutsu 四仏 - Four Buddhas of the Current Age

Shihou Shibutsu 四方四仏 - 4 Buddhas of 4 Directions

In Japanese, their names are:

Godai Nyorai 五大如来, The F ive Buddha of Wisdom ive Buddha of Wisdom

Especially important to the Shingon Sect of Esoteric Buddhsim, the Five Great Buddha of Wisdom (the Five Buddha of Meditation, the Five Jina, the Five Tathagatas, the Godai Nyorai in Japanese) are eminations of the absolute Buddha. They appear frequently on the Japanese Ryokai Mandala. They embody five fundamental wisdoms -- wisdom against anger, envy, desire, ignorance, and pride -- to help us break free from the cycle of death and rebirth (Skt. samsara). Each of the five Buddha has a specific mudra (hand gesture) that corresponds to five defining episodes in the life of the historical Buddha (see Mudra page for details). Each of the five is also associated with a direction (north, south, east, west, center/zenith). The Bosatsu (Bodhisattva) often wear crowns that bear an effigy of their “spiritual father” -- i.e., one of the Five Buddha of Wisdom. The five are:

- Fukujoju Nyorai (Amoghasiddhi)

- Hosho Nyorai (Ratnasambhava)

- Ashuku Nyorai (Akshobhya)

- Dainichi Nyorai (Vairocana or Mahavairocana)

- Amida (Amitabha)

- Click here for details about all five (Godai Nyorai)

|

|

Definitions of fundamental Buddhist concepts and terminology can be found on the Terminology page. For example, the terms Buddha, Tathagata, Nyorai, Butsu, and Hotoke are, for all practical purposes, synonymous in modern English usage. The terms enlightenment, nirvana, emancipation, and satori are likewise synonymous in modern English usage. These and other terms are discussed in detail on the Terminology page.

|

|

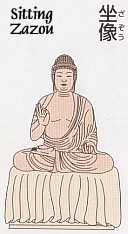

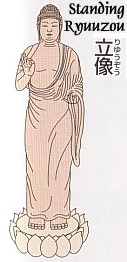

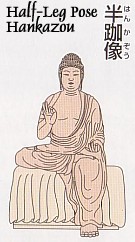

Nearly all statues of the Nyorai and Bosatsu come in three varieties -- standing, sitting, or half-leg pose, with the deity often shown atop a lotus-shaped platform. Less common types show the deity standing on a cloud, kneeling, or riding on an animal like the mythical Shishi, the Peacock, or the Elephant.

The seated/sitting style is known as the Lotus Position.

The half-leg form is called the Half Lotus Position

Above clipart courtesy of:

“How to View Buddhist Statues (As if Wearing Glasses)”

Japanese Language Only, Published by Shogakukan, 2002, ISBN 4093435014

|

LEARN MORE

- Three Main Schools of Buddhism

Timeline. History of Asian Buddhism.

- Buddhist-Artwork.com, our sister site & eStore, launched in July 2006. The store sells quality hand-carved wood Buddha statues & Bodhisattva statues, especially those carved for the Japanese market. Aimed at art lovers, Buddhist practitioners, and laity alike, the estore is not associated with any educational institution, private corporation, governmental agency, or religious group.

|

|