|

|

|

|

THERAVADA SCHOOL

BEFORE BUDDHISM IN JAPAN

This is a side page. Return to Parent Page.

Overview | Hinduism | Theravada  | Mahayana | Vajrayana | Rifts | Mahayana | Vajrayana | Rifts

RELATED PAGES: Early Buddhism in Japan | Comparing Schools | Guide to Buddhism in Japan

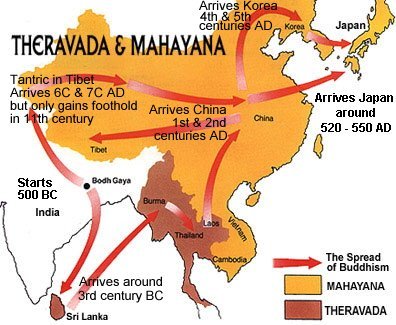

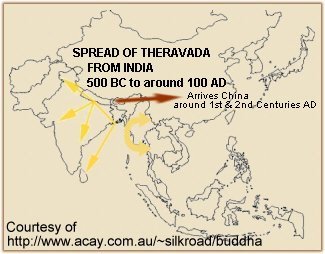

Map courtesy of Buddhanet

Modern scholars prefer to use the term THERAVADA rather than Hinayana. The latter is a pejorative term meaning “Lesser Vehicle.” The term was used (and still is used) by Mahayana devotees to depict Hinayana teachings as inferior to Mahayana teachings |

|

Theravada School (or Hinayana School) Theravada School (or Hinayana School)

Known as the Theravada School, or the School of the Elders (Skt. = Sthaviravada). Also pejoratively referred to as the Hinayana (lit. = Lesser Vehicle) by Mahayana adherents, who claim that Hinayana emphasizes personal liberation/salvation in contrast to the collective liberation of the Mahayana (lit. = Greater Vehicle).

The Theravada (Jp. = Joza Bukkyo, Jōza Bukkyō) or Hinayana (Jp. = Kojyo Bukkyo or Kojyō Bukkyō) school is based on the teachings of its founder, the Historical Buddha. Known also as Gautama Buddha or Prince Siddhartha, the Historical Buddha lived in India from around 560 to 480 BC. For comparative purposes, his contemporaries were Confucius and Lao-tzu (the founder, the “old boy” of Chinese Taoism) -- slightly later in the West comes Plato (427? - 347 BC).

In India, in the four centuries following Gautama’s death, his dialogues and teachings were preserved only in the memory of followers. No written records or artistic representations (except for the footprints of the Buddha) survive into the present age. Like the Hindu Brahmins, the early Buddhists believed that religious knowledge was too sacred to be written down, too sacred to be etched in stone or wood.

|

The Theravadins clearly differentiate between monks and laity. Only those who practice the meditative monastic life (i.e., the monks) can attain spiritual perfection. Enlightenment is not thought possible for those living the secular life. Theravadins revere the Historical Buddha, but they do not pay homage to the numerous Buddha and Bodhisattva worshiped by Mahayana followers. The highest goal of a Theravadin is to become an Arhat (Skt), or perfected saint. (Japanese Rakan or Arakan).

|

|

The early Buddhists split into a number of factions following Gautama’s death, each faction holding firm to its own interpretations. Roughly 500 years later, two main schools emerged -- Theravada (pejoratively called the “Lesser Vehicle”) and Mahayana (“Greater Vehicle”). Theravada sought to preserve the original and orthodox teachings of Gautama Buddha, while the Mahayana tradition was more flexible and innovative. At the time, the distinction between Lesser and Greater Vehicles was politicized into arguments over “benefitting self” and “benefitting others.” Mahayana adherents insisted that only by “benefitting others” could one hope to benefit oneself. To Mahayana followers, the Theravada philosophy is false, for Theravada stresses “self benefit” -- practicing by oneself strictly for one’s own emancipation. See Additional Readings for more on this early schism. The early Buddhists split into a number of factions following Gautama’s death, each faction holding firm to its own interpretations. Roughly 500 years later, two main schools emerged -- Theravada (pejoratively called the “Lesser Vehicle”) and Mahayana (“Greater Vehicle”). Theravada sought to preserve the original and orthodox teachings of Gautama Buddha, while the Mahayana tradition was more flexible and innovative. At the time, the distinction between Lesser and Greater Vehicles was politicized into arguments over “benefitting self” and “benefitting others.” Mahayana adherents insisted that only by “benefitting others” could one hope to benefit oneself. To Mahayana followers, the Theravada philosophy is false, for Theravada stresses “self benefit” -- practicing by oneself strictly for one’s own emancipation. See Additional Readings for more on this early schism.

The modern-day practice of Theravada Buddhism (and Mahayana as well) is based in part on the Four Noble Truths (“Shitai” in Japanese) and the Eightfold Path (“Hasshodo”), both attributed to the Historical Buddha. For a detailed guide to the basic teachings of the Historical Buddha, please click here. The Four Noble Truths are: (1) life is suffering; (2) suffering has cause; (3) eliminate cause and thereby eliminate suffering; (4) learn and pursue the proper path to alleviate suffering (i.e., the Eightfold Path). Suffering is caused by human weakness -- desire, lust, pride, anger, greed and a host of other foibles. The Eightfold Path means the Right View, Right Resolve, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Occupation, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness and Right Concentration. Gautama believed that all life was suffering, and that suffering was caused by desire. He sought, through meditation, to attain a state known as Nirvana, in which one is free of desire and therefore suffering. Nirvana literally means “the state of a flame being blown out.” It represents the quiet state of mind that exists when the fires of attachment and desire are extinguished. It can also refer to the “flame of death.” The death of the Historical Buddha, for example, is referred to as “the Great Extinction.”

The earliest documents of the Historical Buddha’s teachings are found in Pali literature, and are attributed to the Theravadins, the Elders, the first community of followers in India in the early centuries after Gautama’s death. This community of early followers was known, in Sanskrit, as the sangha or samgha. See Additional Readings to learn about their early efforts to recall and codify the teachings of the Historical Buddha.

Lord Buddha’s fundamental teachings are to abstain from evil thinking and action, to purify the mind by practicing ethical conduct and meditation, and through these activities, to develop insight / wisdom (prajna in Sanskrit). The foundations of Buddhist philosophy proclaim that all worldly phenomena is unsatisfactory, transient and impermanent; there is nothing one can call one’s own; the world is an illusion; and our suffering is caused by our clinging to the world of illusion (the world of desire). The goal of the Theravada Buddhist is to attain these insights, internalize them, feel them, live them, and thereafter become an enlightened Arhat.

“The ideal Theravada Buddhist is the arhat (Pali: arahant), or perfected being, one who attains enlightenment as a result of one’s own efforts. A life where all (future) birth is at an end, where the holy life is fully achieved, where all that has to be done has been done, and there is no more returning to the worldly life. (Arhat, the "worthy one," the one who attains the highest level in the Theravada school; the fruition of arhatship is Nirvana, the state of no suffering.)”

quote courtesy 1994-2000 Encyclopedia Britannica

and triple_gem.tripod.com/buddhism/id5.html

Theravada Buddhism is still practiced widely in Southeast Asia, where its principles have been accepted with few differences in interpretation, but Theravada is not practiced widely in Japan. The Theravada school advocates the meditative monastic life as the path to salvation and liberation, a path reserved for those few (the monks) who can give up all to follow its austere practices. In contrast, Mahayana Buddhism (the “Greater Vehicle”) focuses on collective liberation -- not just for monks, but for laity too. The Mahayana school allows the masses to enjoy the pleasures of worldly life while still bringing them the hope of salvation.

Buddhism as practiced today is still divided into three main schools -- (1) Theravada, meaning School of the Elders, but pejoratively known as Hinayana or Lesser Vehicle; (2) Mahayana, meaning Greater Vehicle; and (3) Vajrayana, meaning Diamond Vehicle; also known as Tantric or Esoteric Buddhism. “Yana” is the Sanskrit term for vehicle. The bewildering number of sects are categorized into one of the three schools.

- Theravada (Hinayana)

Found mainly in Sri Lanka, Burma, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand. Often known as the Southern Traditions of Buddhism.

- Mahayana

Found mainly in China, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. Often known as the Northern Traditions of Buddhism.

- Vajrayana (Esoteric or Tantric Buddhism)

Practiced mainly in Tibet, Nepal, and Mongolia, but in Japan has a strong hold with the Shingon 真言, Tendai 天台, and Shugendō 修験道 sects. In Japan, Esoteric Buddhism is known as Mikkyō (Mikkyo) 密教). Along with Mahayana Buddhism, the Vajrayana traditions are often referred to as the Northern Traditions of Buddhism.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THERAVADA IN JAPAN:

|

|