|

|

|

|

EARLY RIFTS IN BUDDHISM

Before its Introduction to Japan

This is a side page. Return to Parent Page.

Overview | Hinduism | Theravada | Mahayana | Vajrayana | Rifts

RELATED PAGES: Early Buddhism in Japan | Comparing Schools | Guide to Buddhism in Japan

Map courtesy of Buddhanet

First Major Rift in Buddhism by Brian Ruhe

When the Lord Buddha died, the monks codified 84,000 lines of his dharma teachings - which were much later made into the “sutras” -- at the First Council, which was held soon after the Buddha’s death around 480 BC. Some 130 years later the sangha (i.e., monks, sometimes spelled samgha) convened the Second Council to stamp out heresies within the religion. Again they agreed upon the same 84,000 lines from the Buddha and nothing of importance has been lost to the present day. It was at this Second Council that we have evidence of the first rift known within Buddhism, the first ever major split in views. This probably occurred in southeast India below the mouth of the Ganges River.

The rift was led by Mahadeva. Mahadeva was a charismatic leader and he resonated with a cord deep in Buddhist society because many lay people objected to the god-like power and respect that enlightened arahants had within temple life. “When the cat’s away the mice will play.” The Buddha wasn’t around anymore to defend the elite position of the arahants - which they rightly deserved. Mahadeva turned against the saints, the women and men who were enlightened, by putting forth his views that the arahants were not yet fully evolved because of five shortcomings. In A Short History of Buddhism the eminent British Buddhist scholar, professor Edward Conze, listed these five as:

- allegedly some arahants were prone to seminal emissions in their sleep

- had nightmares

- were still subject to doubts

- ignorant of many things

- and owed their salvation to the guidance of others (Conze, 1980, 28).

Also at issue was the belief that the sutras were the ultimate authority in Buddhism. Mahadeva held that it was possible for the Buddha’s revelation to come anywhere at anytime, so people shouldn’t have to cling to the sutras. This remains the big issue today.

Mahadeva won the popular debate and thousands of people followed his lead but the established Theravadins renounced their views as a heresy. Mahadeva’s sangha called themselves the Mahasanghikas -- “the great community” -- and more than 60% of all the Buddhists in recorded history can trace back their lineage to this one man.

Two or three centuries after Mahadeva, beginning gradually around 50 B.C., the thriving Mahasanghikas more clearly formulated their new doctrine. They initiated one of the greatest marketing schemes known to human history. They underwent a corporate name change and they called themselves the “Mahayana.” They called the dominant Theravada Buddhist religion of the day, the “Hinayana.” The other Mahasanghikas who didn’t agree to go along with the change were also put down as Hinayanists. The ‘Hinayana’ translates as ‘lesser wheel’ but it also translates as ‘crummy wheel’ or ‘lousy wheel,’ ‘stingy’ or ‘narrow minded’. Using the word ‘Hinayana’ is like using the word ‘nigger’. In this way the Mahayanists attempted to assert their superiority over the Theravadins. This didn’t happen overnight. It began in several of the seven schools of the Mahasanghikas - all now extinct, and even in some of the eleven quasi Theravada schools. By 400 AD the full blown idea of the Mahayana was consummated in the teachings of Asanga.” <end quote Brian Ruhe>

The First Council - The Making of the Buddhist Canon

clubs.mq.edu.au/macbuddhi/articles/different_traditions.html

Soon after the Buddha's passing, five hundred Arahants, or disciples who had attained enlightenment through hearing the teachings of the Buddha, gathered, in what is often called the First Council, to recall and organise the teachings of the Buddha, known as the Dharma. Ananda, who was with the Buddha constantly throughout his life, was asked to recall the sermons that the Buddha had preached. After some discussion, they agreed that what Ananda recalled was essentially what the Buddha had taught. This collection of sermons became known as the Sutta Pitaka or Sermon collection and constitutes the middle collection of the Buddhist canon. Upali, a monk of great learning, recalled the monastic rules and these, after discussion by the monks, were agreed upon. Ananda remembered having been told by the Buddha that some minor rules could, after his passing, be dispensed with, but the major rules must be preserved. During the discussion on this point, the monks could not agree on what constituted the minor rules, so they resolved that all of the rules should be retained. This, to me, seems rather surprising because an examination of the rules shows quite clearly that some rules are considered extremely important entailing expulsion from the order should they be broken.

Four of these major rules are known as Parajika or rules of defeat. Should any of these Parajika rules be broken, the monk, at the instant that it is broken, ceases to be a monk and cannot be re-ordained during the present life. These four important rules are:

- sexual intercourse

- killing a human being

- stealing an object of value

- and claiming to have attained supernormal powers.

The breaking of some other important rules entail disciplining by fellow members of the Sangha. Many of the rules, however, related to rules of etiquette which change over time and differ from one society to another. A breech of these, however, requires nothing more than a promise to try not to break them again - more or less a beating with a feather. These, I would suggest, are what the Buddha may have meant by the minor rules. This collection of the monastic rules is known as the Vinaya Pitaka or Discipline Collection and is the first section of the Buddhist canon.

About 100 years after the passing away of the Buddha, the Second Buddhist Council was called to adjudicate on some monks who were not strictly observing the disciplinary rules of the Vinaya as agreed at the First Buddhist Council. These monks were accused of breaking such rules as handling gold and silver, eating after noon, etc. which they considered to be minor rules and permitted by the Buddha. The Elder Monks, known as the Theras, disagreed and said that these offences should warrant the monks' expulsion from the monastic order. These dissident monks broke away from the orthodox or Theravada monks and formed a new group or schism known as the Mahasanghikas. The Mahasanghikas also disagreed with the Theravadins as to the goal of the Buddhist practice. The Theravadins held that the highest goal that one could attain was that of the Arahant and that the monastic life was the only way that one could attain it. The Mahasanghikas, however, regarded this as a rather elitist attitude. They argued that a Buddhist practitioner, monastic or lay, should strive to become a Bodhisattva (Bosatsu), one who postpones their full enlightenment until they can become a Buddha and thus be instrumental in leading other beings to enlightenment. From the Mahasanghikas, the major tradition of the Mahayana was later to evolve.

By the third century BCE, the Sasana, or Buddhist followers, had split into eighteen sects or schools. The Theravadins had broken into eleven sub-sects whilst the remaining seven were a part of the Mahasanghikas. The divisions into these sects were on minor points of doctrine or on interpretations of the monastic discipline. The essential teachings of the Buddha, the Four Noble Truths, the truth of unsatisfactoriness, its cause - greed anger and a deluded mind and its ceasing and the method for its ceasing, the Noble Eightfold Path of good conduct, one pointedness of mind and wisdom, and Dependent Origination, or interconnectedness of all phenomena, however, were preserved by all sects. Another important teaching to cultivate was known to the Theravadins as the Brahma Viharas or Four Heavenly Abodes and to the Mahayanists as the Four Immeasurables. These four are the cultivation of loving kindness, known in Pali as Metta or in Sanskrit as Maitri, compassion or Karuna, sympathetic joy or rejoicing in the good fortune of others, known as Mudita, and a balanced or non-discriminating mind, known as Upekha. These essential teachings of the Buddha are common to both the Theravada and Mahayana schools so, on these teachings at least, there is no difference between the two traditions.

ABOUT THE MAHASANGHIKAS

manjushri.com/TEACH/mahasanghika.html

buddhanet.net/e-learning/history/b3schmah.htm

It is generally accepted, that what we know today as the Mahayana arose from the Mahasanghikas sect, the forerunners of the Mahayana. They took up the cause of their new sect with zeal and enthusiasm and in a few decades grew remarkably in power and popularity. They adapted the existing monastic rules and thus revolutionised the Buddhist Order of Monks. Moreover, they made alterations in the arrangements and interpretation of the Sutra (Discourses) and the Vinaya (Rules) texts. And they rejected certain portions of the canon which had been accepted in the First Council. According to it, the Buddhas are lokottara (supramundane) and are connected only externally with the worldly life. This conception of the Buddha contributed much to the growth of the Mahayana philosophy.

BUDDHIST MONKS, NUNS, AND LAY BUDDHISTS

uwacadweb.uwyo.edu/religionet/er/buddhism/BGLOSSRY.HTM#vajrayana

As part of the reaction against Hinduism during its early years, Buddhism rejected the caste system and other forms of social stratification and instead set up an essentialy egalitarian society. There are only two religiously important social groups: the monks, who have dedicated their lives to full time pursuit of religious goals, and everyone else. The monks, as a group, are called the sangha (sometimes spelled samgha). The non-monks are referred to as the lay people, or, the laity, for short.

This distinction between the sangha and the laity provides the karmic grease that keeps the wheels of Buddhism running. The monks take a vow of poverty, renouncing the ownership of possessions. They receive their food through daily begging. The lay people accept this practice and give food to the monks, and support them in other ways. In this way, the lay people earn merit (good karma). In turn, the monks provide the laity with religious services, such as officiating at celebrations of birthdays and marriages, giving religious guidance, and so on. This earns the monks merit. As Buddhism spread and became popular, more wealthy people were attracted to it, including kings. Such people gave from their enormous resources, some building large and lavish monasteries, endowing food supplies, giving statues and other objects of precious metals, and so on.

[In India] the monastic movement was predominantly male. At the insistance of some of his early female followers, the Buddha established an order of nuns. The male monks are called Bhikkhu(s) and the female monks are called Bhikkhuni(s). The female monastic orders were never accepted as equals with the male. The nuns were required to follow the monastic rules for the monks, and then an additional set of rules designed for them alone. Ultimately, the female orders were allowed to die out, although they are being reestablished in modern times.

Tantric Buddhism in India by Miranda Shaw

www.tantra.com/mission/shaw.html

TANTRIC Buddhism was the crowning cultural achievement of Pala period India (eighth through twelfth centuries) and an internationally influential movement that swept throughout Asia, where it has survived in many countries to the present day. Tantric Buddhism arose when Mahayana Buddhism was enjoying a period of great philosophical productivity and intellectual influence. Flourishing monastic universities offered a life of study and contemplation but also provided a direct route to tremendous wealth, political influence, and social prestige.

A monk who enjoyed a successful academic career might be given land, servants, animals, buildings, precious metals, jewels, furnishings, art, and the privilege of riding on an elephant in official processions Admiring patrons offered these gifts as tokens of their esteem and as a way to gain religious merit. One monk was even offered the income from eighty villages by an enthusiastic royal patron. The monk declined.

Building upon the great achievements of Mahayana philosophy, yet impelled by a spirit of critique, Tantric Buddhism arose outside the powerful Buddhist monasteries as a protest movement initially championed by lay people rather than monks and nuns. Desiring to return to classical Mahayana universalism, the Tantric reformers protested against ecclesiastical privilege and arid scholasticism and sought to forge a religious system that was more widely accessible and socially inclusive. The Tantrics believed that self-mastery was to be tested amidst family life, the tumult of town and marketplace, the awesome spectacles of a cremation ground, and the dangers of isolated wilderness areas. The new breed of Buddhists also insisted that desire, passion, and ecstasy should be embraced on the religious path. Since they sought to master desires by immersion in them rather than flight from them, the Tantrics styled themselves as "heroes" (vira) and "heroines" (vera) who bravely dive deep into the ocean of the passions in order to harvest the pearls of enlightenment. In consonance with Tantra's daring assertion that enlightenment can be found in all activities, sexual intimacy became a major paradigm of Tantric ritual and meditation.

The Tantric revolution gained popular and royal support and eventually made its way into the curriculum of monastic universities like Nalanda, Vikramasla, Odantapur, and Somapur. These institutes of higher learning were patronized and attended by both Hindus and Buddhists. They featured philology, literature, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, and art, as well as the "inner sciences" of meditation, psychology, and philosophy. While the monasteries served as the institutional strongholds of the faith, wandering lay Tantrics carried Buddhism to the villages, countryside, tribal areas, and border regions, providing an interface at which new populations could bring their practices, symbols, and deities into the Buddhist fold. Practices that had great antiquity in India's forests, mountains, and rural areas, among tribal peoples, villagers, and the lower classes, were embraced and redirected to Buddhist ends. The renewed social inclusiveness and incorporation of an eclectic array of religious practices reshaped Buddhism into a tradition once again worthy of the loyalty of people from all sectors of Indian society. Tantric Buddhism drew adherents from competing faiths, expanded geographically into every region of the Indian subcontinent, and continued outward on a triumphal sweep of the Himalayas, East Asia, and Southeast Asia.

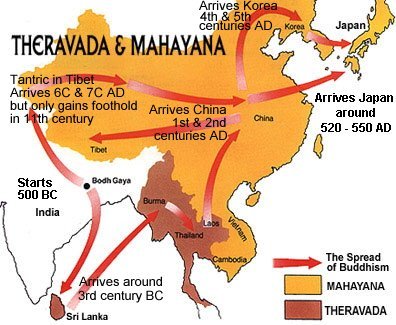

Three Main Schools of Buddhism Today. Buddhism as practiced today is still divided into three main schools -- (1) Theravada, meaning School of the Elders, but pejoratively known as Hinayana or Lesser Vehicle; (2) Mahayana, meaning Greater Vehicle; and (3) Vajrayana, meaning Diamond Vehicle; also known as Tantric or Esoteric Buddhism. “Yana” is the Sanskrit term for vehicle. The bewildering number of sects are categorized into one of the three schools.

- Theravada (Hinayana)

Found mainly in Sri Lanka, Burma, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand. Often known as the Southern Traditions of Buddhism.

- Mahayana

Found mainly in China, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. Often known as the Northern Traditions of Buddhism.

- Vajrayana (Esoteric or Tantric Buddhism)

Practiced mainly in Tibet, Nepal, and Mongolia, but in Japan has a strong hold with the Shingon 真言, Tendai 天台, and Shugendō 修験道 sects. In Japan, Esoteric Buddhism is known as Mikkyō (Mikkyo) 密教). Along with Mahayana Buddhism, the Vajrayana traditions are often referred to as the Northern Traditions of Buddhism.

|

|