|

|

|

|

|

NOTE: This page relies heavily on the wonderful research of the Japanese Architecture & Art Net User System (JAANUS). A visit to their online dictionary is highly recommended. Much of their research on stone lanterns is reproduced below, with their permission. Thank you JAANUS. I would also like to thank Dr. Gabi Greve, a longtime Japan resident, for her assistance, research, and advise. This page is also accompanied by a Photo Tour of the various lantern and grave-marker styles.

Second oldest stone lantern in Japan

Late Heain Era, Kasuga Shrine (Nara).

184 cm, 8-sided-capstone.

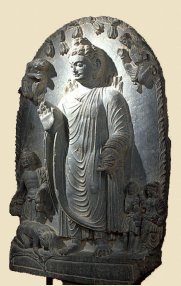

In a tradition unique to Japan, the Tentōki and Ryūtoki creatures in above photo were originally evil, but after getting trampled by the Shitenno (Four Deva Kings), they repented, were saved, and now carry lanterns as offerings to the Historical Buddha (Shaka Nyorai). View the original wood statues at Kōfuku-ji Temple in Nara (Kamakura Era, 1215 AD). Approx. 78 cm in height.

|

|

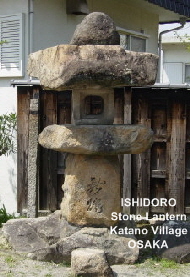

ISHIDŌRŌ / ISHIDORO

JAPANESE STONE LANTERNS

Stone Lanterns, Votive Markers

Offerings of Light, Garden Decorations

See Photo Tour of Various Lantern Styles

See Dōsojin for Protective Stone Markers

See Gorintō for Grave Markers & Reliquaries

See Stones Top Menu for overview of all categories

INTRODUCTION. Ishidōrō 石灯籠 or 石燈篭 (stone lanterns) were introduced to Japan via Korea and China in the Asuka Period (6th century AD), and were used initially as votive lights at temples and later on by shrines. Some centuries passed before they were used for the practical purpose of lighting the grounds of religious precincts. Around the 16th century, stone lanterns were adopted by the secular community and placed in the gardens of tea houses and private residences. The earliest lanterns were designed to hold the sacred flame (the flame itself represents Buddha), but there were no windows or openings to let the light shine forth. The burning lamp is a common metaphor in Buddhist texts; it symbolizes the Buddhist teachings, the light that helps us overcome the darkness of ignorance. Many Buddhist sutras (scriptures) say it is virtuous to offer the light of a lamp to the Buddha, and so, the lanterns in front of Japanese temples and shrines were probably used initially as symbolic offerings or memorials to the Buddha. <Sources: JAANUS, Kyoto National Museum (KNM)>

During the Asuka Period (538 - 645 AD), when Buddhism was introduced to Japan, many Korean artisans made the dangerous sea journey to Japan and took up residence. Korea at the time was under Chinese rule, so these artisans also brought their knowledge of China’s sophisticated culture, artistic techniques, and religious philosophies. The Japanese welcomed them and commissioned them to build Japan’s first temple, the Asuka 飛鳥 Temple in Nara. Artifacts excavated from temple remains include a lantern foundation stone that clearly shows the influence of Chinese technologies. <Source: KNM>

According to Nakamura Yasushi, a conservation officer at KNM, the oldest extant lantern in Japan today is the 1300-year-old-Asuka period lantern at Taima-ji Temple 当麻寺 in Nara. The second oldest comes from the late Heain Era, and is named Yunoki Tōrō (Citrus-Tree Lantern; see photo at right) at Kasuga Shrine 春日大社 in Nara. But the golden age of stone carving in Japan, says Nakamura, was the Kamakura Era (1185-1333 AD), and over 100 Kamakura-era lanterns are still extant today, mostly located in Japan’s Kinki region (Kyoto and Osaka areas). The Kyoto National Museum possesses three Kamakura lanterns.

Lanterns in Garden Design. Says the University of Alberta (home of the Kurimoto Japanese garden): “Stone lanterns were originally votive lamps in the front of Buddhist temples. In the 13th century they began serving the same function in the precincts of Shintō shrines. In the earliest Japanese gardens, lantern designs were borrowed from temples, but in the 16th century, with the development of the tea ceremony, tea masters such as Sen Rikkyu 千利休 (1522-92) began designing lanterns specifically for garden use. The stone lantern, made primarily of granite, became a permanent feature of Japanese garden design thereafter. Garden lanterns are divided into three general styles. The oldest is the Taima-ji 当麻寺 style, named after a temple in Nara that is home to Japan’s oldest extant stone lantern. Over two meters tall, the lamp is comprised of six parts -- pedestal, shaft, middle platform and light compartment, roof and jewel finial. The second style is the Korean temple light. It combines the roof and jewel top, has a very large middle platform and light compartment and a short shaft that gives it a squat appearance. The third style is the creative style especially developed for gardens. This includes a wide variety of shapes unlike anything found in Buddhist temples or Shintō shrines. Representatives of these are the Yukimi or ’Snow Viewing‘ lanterns and Oribe lanterns with no pedestal. <end quote> Today, Ishidōrō stone lanterns are a common feature of private gardens throughout Japan, and these lanterns are often engraved with Sanskrit letters or Buddhist icons.

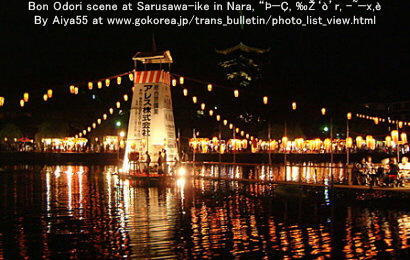

The many lanterns along the approach to Kasuga Shrine in Nara are

among the best known in Japan. In February & August each year

they are lit up for Japan’s popular lantern festivals (see immediately below).

OFFERINGS OF LIGHT OFFERINGS OF LIGHT

Tōmyō Kuyō, Tomyo Kuyo, 灯明供養

Lighting Ceremony for the Deceased

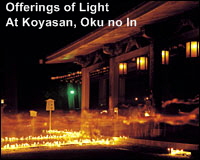

Mt. Kōya 高野山 (Kii Peninsula, Wakayama Prefecture) is the sacred mountain of Japan’s Shingon Sect of Esoteric Buddhism. A mountain monastery called Kongōbuji 金剛峰寺 was established here in 816 AD by Kūkai 空海 (aka Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師; 774 - 835 AD; founder of Japan's Shingon Sect). Kūkai (Kukai) is also intimately associated with the Shikoku Pilgrimage. Since its founding until today, Kongōbuji (Kongobuji) has served as the center of Shingon Buddhism in Japan, and Mt. Kōya (Koya) remains one of modern Japan's most popular pilgrimage sites. The monastery is a vast repository of Buddhist art, especially mandalas, stone lanterns and moss-covered gravestones. Dainichi Nyorai and Fudō Myō-ō are two of the sect's most revered deities. Kōbō Daishi's name literally means "great teacher of Buddhism." He is also credited with creating Japan's hiragana syllabary.

The holiest place at Kōyasan is the innermost temple (Oku no In 奥の院), which houses the tomb of Kōbō Daishi. In front of the mausoleum is the Hall of the Lamps (Lantern Hall, Tōrōdō 灯篭堂). Says Frommer’s Guide to Kōyasan: “Two sacred fires, which reportedly have been burning since the 11th century, are kept safely inside. Buy a white candle, light it, and wish for anything you want. Then sit back and watch respectfully as Buddhists and pilgrims from around the nation come to chant and pay respects. The Lantern Hall houses thousands of lanterns, donated by prime ministers, emperors, and others. If you'd like to buy a lantern to dedicate to someone, it costs from 500,000 yen to 1,000,000 yen. You can also rent a lantern for a period of time as a religious service to a lost soul or relative. For three days you pay 1000 yen, for a whole year about 500 dollars. The ceiling of the hall is resplendent with these lamps, and in the vicinity are rows and rows of hanging lanterns, on which are written the name of the deceased and the time/date until the lamp will remain burning.” <end Frommer’s quote>

OFFERINGS OF LIGHT. Below text courtesy of Dr. Gabi Greve. The Offering of Light (Tōmyō 灯明; Sanskrit = diipa; ceremony associated with the deceased), together with incense, flowers, water and other things to please the deities, is a custom that originated in India with the spread of Buddhism. First, oil from plants was used, later candles and nowadays, of course, electric lights. The symbolism of light in the Buddhist context is to "tear away the darkness of illusion through the all-penetrating light of the Buddha." The Buddha light brings wisdom and compassion to all humankind, and, it is said, at the end of your life, it will lead you to the Western Paradise. The well-known "Hall of Lanterns" (see above) at Mt. Kōya is a place for people to make the offering of light. Legend says that, in 1016 AD, the Monk Kishin saw a bright light on the moss in front of Kūkai's mausoleum. So he placed a candle on that spot and lit it. According to legend, the light of that candle has never ceased burning. Today this “never-ending” light is known as Kiezu no Tōmyō 消えずの灯明. Other temples have their own never-ending light, which is generally refered to as Jōyatō.

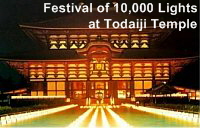

Light offerings are an important ritual at many temples even today. One prominent example is the "festival of ten thousand lights" at Tōdaiji Temple. This light festival, known as Mandō-e 万灯会, is held on August 15 each year, during the Obon festival period. More than 2,500 graves around the temple are all lit with candles. In Esoteric Buddhism, moreover, votive offerings are specifically associated with certain Bodhisattva (Bosatsu), known as the Offering Bosatsu (Kuyō Bosatsu 供養菩薩). The one most closely associated with offerings of light is Kongōtō Bosatsu 金剛灯菩薩. Offerings of light are also customary in Japanese Buddhist funerals. After the funeral, it is customary to keep a light, called the Mujintō 無尽灯, burning for 49 consecutive days. Japan's many fire festivals (Hi-matsuri 火祭り) may also be connected to this belief in the offering of light to the deities. Elsewhere, the Lotus Sutra (Hoke-kyō 法華経) describes seven deities who are especially associated with offerings of light. Light offerings are an important ritual at many temples even today. One prominent example is the "festival of ten thousand lights" at Tōdaiji Temple. This light festival, known as Mandō-e 万灯会, is held on August 15 each year, during the Obon festival period. More than 2,500 graves around the temple are all lit with candles. In Esoteric Buddhism, moreover, votive offerings are specifically associated with certain Bodhisattva (Bosatsu), known as the Offering Bosatsu (Kuyō Bosatsu 供養菩薩). The one most closely associated with offerings of light is Kongōtō Bosatsu 金剛灯菩薩. Offerings of light are also customary in Japanese Buddhist funerals. After the funeral, it is customary to keep a light, called the Mujintō 無尽灯, burning for 49 consecutive days. Japan's many fire festivals (Hi-matsuri 火祭り) may also be connected to this belief in the offering of light to the deities. Elsewhere, the Lotus Sutra (Hoke-kyō 法華経) describes seven deities who are especially associated with offerings of light.

Seven Deities of Light Offerings

- Jōkōbutsu 定光仏

- Tōmyōbutsu 燈明仏

- Niman Tōmyōbutsu 二萬燈明仏

- Sanman Tōmyōbutsu 三萬燈明仏

- Nichi-gatsu Tōmyōbutsu 日月燈明仏 (Buddhas of Sunlight & Moonlight)

- Myōkō Bosatsu 妙光菩薩

- The above deities belong to a grouping known as the “Secret Buddha of the 30 Days” (Sanjūnichi Hibutsu 三十日秘仏). For a complete listing of the 30 deities, please see this J-site.

- There is also Nentō Buddha, who is not often represented in Japanese artwork. Also called the Buddha of Burning Light (Jp. = Daiwaketsura 大和竭羅; Skt. = Dīpaṃkara, Dapankara, Dipankara, Dpankara). Says the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (user name = guest): “The Buddha of Burning Light, the 24th predecessor of Śākyamuni (the Historical Buddha), a disciple of Varaprabha.” <end DDB quote> Click here for a few more details about this deity. <end quote by Dr. Gabi Greve>

|

|

|

|

Gangōji Temple 元興寺 (Gokuraku-bō 極楽坊) in Nara

|

|

|

|

JAPANESE LANTERNS JAPANESE LANTERNS

Tōrō (Toro) 燈篭、灯篭

Below text courtesy JAANUS. The Japanese characters for stone lantern 燈篭 can also be written 灯篭. The earliest lanterns were introduced to Japan from China through Korea along with Buddhism in the 6th century. Several types of lanterns were popular in Japan:

- ISHIDŌRŌ (Ishidoro) 石灯籠. Stone lanterns. First used as votive lights at temples and shrines. Later they were used to light the ground of these religious precincts. Secular use began in the 16th century when stone lanterns were used by tea masters for gardens surrounding their tea huts. There are about nine major categories of stone lanterns based on general shapes and over 75 sub-categories. All include a hollowed-out upper section which hold a light. See JAANUS for an excellent photo tour of the various lantern styles.

- TSURIDŌRŌ (Tsuridoro) 釣灯篭. Hanging metal lanterns usually of bronze or iron, were hung from the corner eaves at palatial residences, temples and shrines. See JAANUS for details and photo.

- ANDON 行灯. Standing oil lanterns had iron or wood frames. There were many different shapes and sizes which burned oil in shallow saucers suspended within a frame covered with paper. This type of lantern became popular during the Edo period and was used in private homes.

- BOMBORI (Bonbori) 雪洞. Portable lanterns were distinctively hexagonal, with wood or metal frames covered with paper, or glass in later years. They generally had poles attached horizontally to the top of the frame for ease of transportation. For a tour of the popular annual bonbori festival in Kamakura, please click here.

- CHŌCHIN 提灯. Paper lanterns were used outside the house and suspended from the eaves of buildings or carried in processions. The frame was a collapsible structure of thin bamboo strips covered with paper. A candle was placed inside. Chōchin were made in various sizes, shapes and colors and were often decorated with the names or logos of restaurants or inns. <end JAANUS quote> <Below text courtesy of L'Asie Exotique> When a Westerner thinks of a Japanese lantern, the first object that springs to mind is the chōchin, a collapsible lantern crafted of bamboo and covered with oiled paper. It is stretched out like an accordion when in use, but collapsed when not in use. Chōchin can be hung or carried as a traveling lantern. The shapes vary tremendously from prefecture to prefecture. These lanterns were originally illuminated by candles. Replications can still be seen in Japan, outfitted electrically. Unfortunately, Edo-period chōchin rarely exist today since the nature of their design is somewhat fragile and does not sustain endured use. <See photo of red & white lanterns above>

Stone Lanterns at Buttsuu-ji Temple 佛通寺. Photo by Dr. Gabi Greve

|

ABOVE PHOTO: This Zen temple (Rinzai Sect) was founded in 1397 with the help of priest Gūchū. Today it is one of Japan's biggest Zen mountain temples. It features retreats every month and also welcomes foreigners. Located near Hiroshima. The temple is also quite beautiful in the autumn as the maple trees turn red. For more photos of the temple, please visit Gabi Greve’s photo gallery.

|

|

|

GLOSSARY OF KEY WORDS

Not inclusive. See above text for more words & definitions.

|

|

Japanese

|

Hiragana

|

English

|

|

灯籠 or

灯篭

|

とうろう

|

Tōrō, Toro, Dōrō, Doro. Meaning = Lantern. The earliest were introduced to Japan from China through Korea along with Buddhism in the 6th century. See above for details and images. A good pictorial review can be found here by JAANUS.

|

|

石灯籠

石燈篭

|

いしどうろう

|

Ishidōrō, Ishidoro. Meaning = Stone Lantern. Also written 石灯籠. See above for details and images.

|

|

粘土五輪塔婆

|

ねんど

ごりんとうば

|

Nendogorintōba, Nendogorintoba. Meaning = Clay Lantern.

|

|

金灯篭

|

かなどうろう

|

Kanadōrō, Kanadoro. Meaning = Metal Lantern.

|

|

八角型

|

はっかくけい

|

Hakkakukei. Meaning = Octagonal Type Lantern.

|

|

釣り灯篭

釣り燈篭

|

つりどうろう

Photo courtesy of L'Asie Exotique. Visit their site for a fun review of illumination in Edo-period Japan

|

Tsuridōrō, Tsuridoro. Tsuridōrō, Tsuridoro.

Meaning = Hanging Lantern.

|

|

瑠璃燈篭

|

るりどうろう

|

Ruridōrō, Ruridoro.

Meaning = Hanging lantern made of lapislazuli.

|

|

輪燈

|

りんとう

|

Rintō, Rinto. Rintō, Rinto.

Meaning = Round Hanging Lanterns

|

|

燈明供養

灯明供養

|

とうみょう くよう

|

Tōmyō Kuyō, Tomyo Kuyo. Meaning = Buddhist ceremony of offering light to the deities. The burning lamp is a common metaphor in Buddhist texts; it symbolizes the Buddhist teachings, the light that helps us overcome the darkness of ignorance. Tōmyō 燈明 refers to the lamp hung before a Buddha as a symbol of his wisdom. Kuyō 供養 means offering. Many Buddhist scriptures, or sutras, say it is virtuous to offer the light of a lamp to the Buddha, and so, the lanterns in front of temples and pagodas were probably used initially as symbolic offerings to the Buddhas.

|

|

燃燈供養

然燈佛

燃燈佛

錠光

提竭

提和竭

大和竭羅

錠 also means an oil lamp.

Photo courtesy of Miho Museum

For text details, click here.

|

ねんとう くよう

|

Nentō Kuyō, Nento Kuyo. Nentō Kuyō, Nento Kuyo.

Meaning = Light Offerings to Nentō Buddha, the Japanese name for Dīpaṃkara Buddha (Sanskrit), who in Japan is also known as Daiwaketsura 大和竭羅, the Buddha of Burning Light. Nentō Buddha was the 24th predecessor of Shaka Nyorai (the Historical Buddha). Nentō always appears when the Buddha preaches the themes of the Lotus Sutra. In the second lifetime of Shaka’s incalculable eons of practice, he assured Shaka that he (Shaka) would attain Buddhahood.

Dīpaṃkara (Dipankara), the Buddha of Fixed Light. Sometimes equated with Adibuddha, the "Original Buddha." Since about the 17th century his cult has been popular with Nepalese Buddhists who consider him a protector of merchants and associate him with alms-giving. One of Dipankara's local names, the "Samyak god," refers to an alms-giving festival. Nentō Buddha is rarely represented in Japanese artwork.

|

|

燈燭

|

とうしょく

|

Tōshoku, Toshoku. Meaning = Funeral Lanterns.

|

|

燭台

燈台

灯台

|

しょくだい

|

Shokudai, Tōdai, Todai. Shokudai, Tōdai, Todai.

Meaning = Candle Holder.

Usually found at the four sides of an alter to provide light; when equipped with many arms, it is called a tatōgata tōdai (tatogata todai); with chrysanthemum decorations it is called kikutōdai (kikutodai) 菊燈台.

|

|

行燈

行燈絵

Descriptions

courtesy

JAANUS

|

あんどん

|

Andon 行燈 or Andon-e 行燈絵. ANDON are standing oil lanterns (andon 行灯) with iron or wood frames. There were many different shapes and sizes which burned oil in shallow saucers suspended within a frame covered with paper. This type of lantern became popular during the Edo period and was used in private homes. Oil dishes called aburazara 油皿 were placed under this portable lantern. They were used frequently by many households until the electric light took over. ANDON-E are paintings on paper lanterns that adorn temple and shrine precincts and the gates of residences during a festival. Generally, a well-known personage or artist would decorate these lanterns with written characters and painted designs, but because the lanterns then were displayed outdoors, it was difficult to preserve them. Some examples remain today, as do some of the preliminary sketches for the designs before they were brushed onto the lanterns. Images of these painted paper lanterns can be seen in multi-colored prints by Utagawa Kunisada 歌川国貞 (Toyokuni III 三代豊国;1786-1864) and Keisai Eisen 溪斎英泉 (1791-1848) and in painted handscrolls by Kuwagata Keisai 鍬形(けい)斎 (1764-1824).

|

|

火袋

Description

courtesy

JAANUS

|

ひぶくろ

|

Hibukuro. Pocket-like or box-like space in a fire box or stove (kamado 竈) where the fuel is burned. Also the place where the fire is lighted in a stone lantern. It is located below the hood (kasa 笠) of the lantern and is hollowed out before the hood is added. The shape of the hibukuro varies. It may be round, square, hexagonal or octagonal. The light openings are not limited to the basic geometric patterns but may include quarter or half moons and other imaginative openings. The fire itself is usually produced by lighting an oil wick. Very often paper pasted to a wooden frame covers the openings to give a soft, pleasant glow.

|

|

笠

Description

courtesy

JAANUS

|

かさ

|

Kasa. Literally “umbrella.” The part of a stone lantern that acts as an umbrella over the fire box (hibukuro 火袋; see above entry). Usually kasa are square or hexagonal, but only rarely octagonal. Occasionally, they are round. The roof line, from the top to the edge, is usually constructed in a convex-concave pattern, but it may be cambered or given a wavy outline. At the intervals dividing the kasa into sections, there are raised strips called kudarimune 降棟. These terminate in scroll or spiral embellishments called warabide 蕨手.

|

|

石幢形石灯籠

Description

courtesy

JAANUS

|

せきどうがたいしどうろう

|

Sekidōgata Ishidōrō, Sekidogata Ishidoro. Meaning = Type of stone lantern shaped like a Buddhist memorial (sekidō 石幢), it has a hexagonal or octagonal base with a faceted pillar on it. On top of the pillar is the fire box, topped with canopy and sacred jewel, common to most stone lanterns. The special characteristic of the Sekidōgata Ishidōrō are the Six Buddha carved in relief on each face of the fire box. Originally derived from the sekidō, a monument displaying Buddhist relief carvings, it is thought that the fire hole was carved out to adapt the monument to function as a lantern.

|

|

マリア灯籠

Description

courtesy

JAANUS

|

マリアとうろう

|

Maria Tōrō, Maria Toro. Meaning = Oribe-type lantern (oribe dōrō 織部灯籠) with an image of Christ or the Virgin Mary carved on the base (sao 竿). Also referred to as a "Christian" lantern (kirishitan dōrō). Relatively small-scale, with the base directly planted in the ground, and a square canopy topped with the jewel form (hōju 宝珠). This type of lantern became popular from the late 16th century.

|

|

万燈篭

|

まんとうえ

|

Mantō, Manto, or Mantō-e. Meaning = Ceremony or procession of people holding lanterns. Also called the “Candle Light Festival.” See Todaiji Temple above. Other related terms include Setsubun Mantōrō 節分万燈篭 and Kannon Mantō-e 観音万燈会.

|

|

SOURCES

RELATED TOPICS AT THIS SITE

OUTSIDE RESOURCES

|

|