|

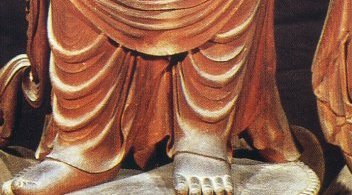

Annami 安阿弥, also called Annamiyō 安阿弥様. The famed Kamakura-era sculptor Kaikei is credited with creating an independent sculptural style known as Annami. The Annami style retains the realism of the Kamakura-era Keiha school, from whence it sprang, but it also introduced a new delicate beauty, one featuring great attention to detail, sharp and graceful carving of robes and elegantly ordered drapery, faces with charm and dignity, and an overall “low-key” elegance. The name of this style stems from Kaikei’s own unique inscription, for he signed many of his works “Kaikei of the Buddhist name AN AMIDA BUTSU,” writing AN in Sanskrit. He received this special Buddhist name from his friend, the Buddhist priest Chogen 重源 (Chōgen, +1121-1206), the latter a famous monk who introduced the so-called Daibutsu Style (Daibutsuyō 大仏様) of architecture to Japan, which he had learned while visiting China. Chogen was a fervent believer in Amida Buddha 阿弥陀如来 and Pure Land faith (Jōdokyō 浄土教), and from +1183 he started giving his friends Buddhist names that contained the name Amida. Following Kaikei’s death, the Annami style was copied, stereotyped, and formalized to such a degree that it ultimately lost much of its earlier brilliance and beauty. Annami 安阿弥, also called Annamiyō 安阿弥様. The famed Kamakura-era sculptor Kaikei is credited with creating an independent sculptural style known as Annami. The Annami style retains the realism of the Kamakura-era Keiha school, from whence it sprang, but it also introduced a new delicate beauty, one featuring great attention to detail, sharp and graceful carving of robes and elegantly ordered drapery, faces with charm and dignity, and an overall “low-key” elegance. The name of this style stems from Kaikei’s own unique inscription, for he signed many of his works “Kaikei of the Buddhist name AN AMIDA BUTSU,” writing AN in Sanskrit. He received this special Buddhist name from his friend, the Buddhist priest Chogen 重源 (Chōgen, +1121-1206), the latter a famous monk who introduced the so-called Daibutsu Style (Daibutsuyō 大仏様) of architecture to Japan, which he had learned while visiting China. Chogen was a fervent believer in Amida Buddha 阿弥陀如来 and Pure Land faith (Jōdokyō 浄土教), and from +1183 he started giving his friends Buddhist names that contained the name Amida. Following Kaikei’s death, the Annami style was copied, stereotyped, and formalized to such a degree that it ultimately lost much of its earlier brilliance and beauty.

Busshi 仏師. Sculptor of Buddhist statues. The term literally means “Buddhist Master” or “Buddhist Teacher.” Sculptors were also called Bukko (Bukkō) 仏工 or Zobusshi (Zōbusshi) 造仏師. The term Busshi appeared in the early Asuka Period (+552-645) when artisans received commissions from the Japanese court and nobility to create Buddhist statues. The most widely acclaimed sculptor in those days was Kuratsukuri no Tori 鞍作止利, more properly known as Tori Busshi. Busshi 仏師. Sculptor of Buddhist statues. The term literally means “Buddhist Master” or “Buddhist Teacher.” Sculptors were also called Bukko (Bukkō) 仏工 or Zobusshi (Zōbusshi) 造仏師. The term Busshi appeared in the early Asuka Period (+552-645) when artisans received commissions from the Japanese court and nobility to create Buddhist statues. The most widely acclaimed sculptor in those days was Kuratsukuri no Tori 鞍作止利, more properly known as Tori Busshi.

Busshi Keizu 仏師系図. A lineage chart or genealogy table tracing the line of a Busshi (sculptor). This tradition arose around the 11th century, when leadership of a workshop was typically a hereditary position. However, direct descendants, adopted sons, and pupils were often included in these charts, making it difficult to distinguish between those with or without direct blood ties. The situation is further complicated by disagreement among modern scholars who claim these lists are inaccurate. See Daibusshi below for details.

Bussho 仏所. Workshop for making Buddhist statues. The term refers to the independent workshops and temple-run workshops that appeared in the 9th century onward. They replaced the government-run workshops Zobussho (Zōbussho) 造仏所 of the prior Asuka and Nara eras, which were closed down shortly before the capital transferred from Nara to Heiankyo 平安京 (Heiankyō; modern-day Kyoto) in +794. One of the primary goals of the transfer was to limit the involvement of the powerful Buddhist monasteries in court affairs. One of Japan’s most renowned Bussho was run by the acclaimed sculptor Jōchō 定朝 (d. +1057), who trained and inspired a generation of artists who then established three of Japan’s most powerful workshops -- the Enpa and Inpa workshops in Kyoto, and the Kei workshop in Nara. Bussho literally means “Buddha Place,” a facility devoted to making Buddha statues. The facility was often sub-divided into distinct areas devoted to specific tasks. For example, the workshop for casting metal was called the Chusho 鋳所 (Chūsho; lit. = Metal-Casting Place). The Bussho System was officially discarded in the 19th century. Bussho 仏所. Workshop for making Buddhist statues. The term refers to the independent workshops and temple-run workshops that appeared in the 9th century onward. They replaced the government-run workshops Zobussho (Zōbussho) 造仏所 of the prior Asuka and Nara eras, which were closed down shortly before the capital transferred from Nara to Heiankyo 平安京 (Heiankyō; modern-day Kyoto) in +794. One of the primary goals of the transfer was to limit the involvement of the powerful Buddhist monasteries in court affairs. One of Japan’s most renowned Bussho was run by the acclaimed sculptor Jōchō 定朝 (d. +1057), who trained and inspired a generation of artists who then established three of Japan’s most powerful workshops -- the Enpa and Inpa workshops in Kyoto, and the Kei workshop in Nara. Bussho literally means “Buddha Place,” a facility devoted to making Buddha statues. The facility was often sub-divided into distinct areas devoted to specific tasks. For example, the workshop for casting metal was called the Chusho 鋳所 (Chūsho; lit. = Metal-Casting Place). The Bussho System was officially discarded in the 19th century.

Daianji Yoshiki 大安寺様式 (Yōshiki). Daianji Temple served as an important government-run workshop making Buddhist statues during the Nara period and early Heian era, and the rare statues remaining in its collection are known as Daianji-Yoshiki, literally "in the Daianji style." The temple was originally named Kumagori Shōja 熊凝精舎 before moving several times to its final location in Nara. One of the Seven Great Temples of Nara, the temple today lies mostly in ruin, a sad reminder of its former glory, although it still houses some wonderful wood statues for viewing, including an 11-Headed Kannon and Bato (Horse-Headed) Kannon. Characteristics of the Daianji style include massive sizes, bold expressions, and elaborate representations. Representative examples are the statues of the Four Heavenly Kings -- the Shitenno (Shitennō) 四天王, made around +791, but greatly restored in the last half of the 13th century. The four statues have been relocated, and are now housed at Koufukuji (Kōfukuji) Temple 興福寺 in Nara. Daianji’s official web site (Japanese language only) is here.

Shitenno (Shitennō) 四天王, or Four Heavenly Kings

Painted wood-core dry lacquer (Mokushin Kanshitsu 木心乾漆)

Heights vary from 125 cm to 139.7 cm.

Kofukuji (Kōfukuji) Temple 興福寺, Nara Era, Dated +791

Daibusshi 大仏師. Also known as Zōbutsu Chōkan 造仏長官 or Daibusshi-shiki 大仏師職. The head master of a temple workshop or independent workshop making Buddhist statues. The workshop leader was responsible for directing and coordinating a team of assistants, the latter known as Shōbusshi 小仏師. By the late Heian era, the introduction of the Yosegi Zukuri 寄木造 (joined-block) technique for making large wooden statues also made mass production feasible, and some workshops at the time employed several hundred assistants to carry out large-scale commissions from the court and nobility. The term Daibusshi first appeared in the Nara era. One of the most famous Daibusshi from that period was Kuninaka no Kimimaro 国中公麻呂 (d. 774). At temple-run workshops, the Daibusshi was typically a monk, but one no longer responsible for performing religious functions. By the time of the famous layman sculptor Jōchō 定朝 (d. 1057), the Daibusshi at temple workshops and at independent workshops were awarded honorary titles that gave them lofty social rank and high-priest status. In addition, by the 11th century, the position of Daibusshi was typically a hereditary position, given to both monk sculptors or independent artists (those who had not joined the monastic order). From this tradition arose the lineage chart or genealogy table (Busshi Keizu 仏師系図), which attempted to record the lineage of each school.

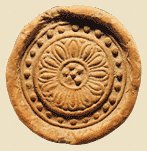

Domon 土紋. Less commonly written 土文. Decorative drapery made from clay. This method of ornamentation appeared in the late 13th century and is unique to the Kamakura area. It featured exceptionally deep drapery folds made with clay molds, or clay decorative elements in the shape of crests, flowers, and leaves. The finished clay relief was then affixed to the statue, often using lacquer. For further details on drapery, see the Emon entry below, or visit the Drapery page.

Above Photo, Below Photo. The Nyoirin Kannon 如意輪観音 statue at Raikoji (Raikōji) Temple 来迎寺 in Kamakura features a beautiful "domon" 土紋, or clay crest. The domon technique was used for decorating Buddhist statues and is unique to Kamakura, and is thus also known as Kamakura Domon 鎌倉土紋. Clay is kneaded 練 (neru) into patterns or placed in molds and then affixed to the statue with lacquer, resembling a relief. The crests on this statue are said to ward off evil (厄除け yakuyoke) and to ensure easy delivery (安産 anzan) to women in labor. Statue dated to 14th century.

Legend About This Statue: A sad story about the Nyoirin Kannon tells about a man in Yui (由比), who was living a luxurious life, with not a care in the world. The man had a daughter he loved very much, but one day a large eagle swooped down and carried her off. The father frantically searched for his daughter, and although he eventually found her, she was dead. He interred her remains inside the body of this Nyoirin Kannon for the repose of her soul. <legend quoted from the Kamakura Citizens Net, as told by the temple>

EXTANT EXAMPLES OF DOMON

Technique unique to Kamakura, emerging in the late 13th century

- Denshu-an (Denshūan), a sub-temple of Engakuji Temple 円覚寺. Wood statue of Jizo (Jizō) Bosatsu 地蔵菩薩像 with domon drapery, dated to the Kamakura period. Located in Kita Kamakura.

- Hokaiji (Hōkaiji) Temple 宝戒寺, Kankiten 歓喜天; a Hidden Buddha 秘仏 (hibutsu) not shown to the public; wood, domon drapery, approx. 155 cm in height; dated to late Kamakura period; said to be the oldest statue of Kankiten in Japan; located in Kamakura city.

- Jochiji (Jōchiji) Temple 浄智寺, Idaten 韋駄天, Wood statue with domon drapery, Muromachi period, although head and hands remade in Edo period, now housed at the Kamakura Kokuhoukan (Kamakura Museum) 鎌倉国宝館 in Kamakura city.

- Jokomyoji (Jōkōmyōji) Temple 浄光明寺, Wood, Amida Triad 阿弥陀三尊, with domon drapery on central Amida 阿弥陀如来 statue; dated to Kamakura period. Located in Kamakura City. Considered to be the oldest extant example of the domon technique featuring exceptionally deep drapery folds; dated to +1299.

- Kakuonji Temple 覚園寺, Amida Nyorai 阿弥陀如 statue, also known as Saya Amida (鞘阿弥陀), for inside the statue was found another small Buddha statue; the term "saya" means sheath or case, and thus the large statue became known as Saya Amida; wood statue with domon drapery, although the domon patterns are no longer clear; dated to Kamakura period; located in Kamakura city.

- Kamakura Kokuhoukan (Kamakura Museum) 鎌倉国宝館; domon fragments in its collection; museum located on grounds of Tsurugaoka Hachimanguu Shrine 鶴岡八幡宮, in Kamakura City. Other domon fragments in collections of private individuals.

- Raikoji (Raikouji) Temple 来迎寺, Nyoirin Kannon 如意輪観音像, Wood with domon crests (see photos above). Dated to Nanbokuchō Period 南北朝時代. Located in Kamakura city.

- Tokeiji (Tōkeiji) Temple 東慶寺, Sho (Shō) Kannon 聖観音, Wood statue with domon drapery; Dated to late Kamakura period. Located in Kita Kamakura.

Drapery. See the Drapery Main Page.

Ebusshi 絵仏師. Professional painters and decorators of religious works hired by the various government-run, temple-run and independent workshops.

Emon 衣文. Folds in the Garment. Sculpting styles for drapery folds underwent significant changes over the centuries. An understanding of these changes helps art scholars to identify and date extant statuary. In the early Asuka period, for example, drapery was typically angular and rigidly geometrical, as exemplified by the bronze Shaka Triad 釈迦三尊 at Horyuji (Hōryūji) Temple 法隆寺 in Nara. In the late Nara and early Heian periods came the Rolling Wave (Honpashiki Emon 翻波式衣文) and Rippling Wave (Renpashiki Emon 漣波式衣文) styles. Both aimed to achieve a wave-like pattern of regularity by alternating between deep and shallow (or wide and narrow, high and low) folds. Representative examples are the sitting Shaka Nyorai 釈迦如来 statue at Muroji (Muro-o-ji) Temple 室生寺 in Nara and the standing Jūichimen Kannon 十一面観音 statue at Hokkeji Temple 法華寺, also in Nara. By the late Heian era, the acclaimed Jōchō Busshi perfected a drapery style that employed wide and shallow folds running in parallel. Jōchō’s extant Amida Nyorai 阿弥陀如来 statue at Byodoin (Byōdōin) Temple 平等院, and its drapery, have been copied endlessly since then. Finally, the Kamakura period introduced a number of innovations, including realistic folds and irregular folds influenced by Sung China, and exceptionally deep drapery folds called Domon. Please see the Drapery page for photos of the pieces mentioned above and more details.

En School or Enpa School 円派. A powerful group of Kyoto-based sculptors who sprang from the workshop of Jocho. Most artists of this school used the character EN 円 in their names, hence the school is named Enpa (pa 派, also pronounced ha, is the character for “school” or faction.) The Enpa school created refined and elegant statuary for the court and nobility in Kyoto, and essentially monoplized the patronage of the imperial court along with their rival, the Inpa School, in the second half of the Heian period. The two schools are collectively known as the Kyoto Busshi, since their main workshops were located in Kyoto. The Enpa School’s principal workshop was at Sanjo Bussho 三条仏所 (Sanjō Bussho) in Kyoto, but Enpa sculptors also set up workshops in regional centres outside Kyoto, including workshops in Fukushima and Kamakura. The Enpa school remained active through the Muromachi period (15th and 16th centuries). See the Heian-era page for many more details on the Enpa School and reviews of its main sculptors.

Fujiwara Style 藤原. A style of Buddhist sculpture that emerged in the middle Heian period, from around +894 to +1185, so-called because the powerful Fujiwara clan dominated political affairs for many of these years, with some serving as regents of the emperors. Their influence and taste for opulent lifestyles brought ever-increasing luxury to court life in Kyoto. This period also marked a break in formal trade with China, with Japanese missions to the mainland discontinued in +894. This break with China provided an opportunity for a truly native Japanese culture (Kokufū Bunka 国風文化) to flower, and from this point forward indigenous secular art becomes increasingly important. In Buddhist sculpture, a new sense of refinement and elegance and softness emerged, which climaxed with the work of Jocho, the period’s most acclaimed sculptor. Statuary also became increasingly decorative, reflecting the tastes of the Fujiwara leaders, including the elaborate use of Kirikane (gold-cut) drapery patterns and applied jewelry to period statuary. One of the monuments of Fujiwara influence from this period is the Byodoin Temple (平等院 Byōdōin), near Kyoto, which Fujiwara Yorimichi 藤原頼道 (+992-1074) converted from a former villa. It houses outstanding examples of Heian-era statuary, as well as the only extant statue made by Jocho. This large-scale extant installation of 50-plus Buddhist statues, completed in +1053, provides many examples of Jocho's talent as a project leader and his team’s widespread adoption of the relatively new statue-making techniques known as Warihagi 割矧 (split-and-join method) and Yosegi Zukuri 寄木造 (assembled-wood method).

Fujiyama Bussho 富士山仏所. An offshoot of the Tsubai Bussho 椿井仏所. Thought to have emerged sometime in the 15th century but subsequently declined in the 16th century.

Gaso 画僧 (Gasō). Monks, Buddhist practitioners, and religious artists who painted Buddhist themes to gain spiritual merit. The term Gaso was used expressively to differentiate such painters from the professional Ebusshi 絵仏師, the latter employed by temple workshops and independent workshops to paint and decorate for religious projects commissioned by the court and nobility. See JAANUS for a list of famous Japanese Gaso painters, many affiliated with Japan’s Shingon 真言 Sect of Esoteric Buddhism and later with Japan’s Zen 禅 sects.

Hogen 法眼 (Hōgen). Literally “Seal of the Law.” The second highest rank awarded to Buddhist sculptors. Starting around the 11th century, the Japanese imperial court began awarding Buddhist sculptors with ranks and titles that were formerly reserved only for Buddhist monks. By the 15th century, important laymen scholars, warriors, poets, writers and other artists were also give such awards. The three highest titles were:

- Hōin 法印 (Hoin). Highest rank. Lit. = eye of the law.

- Hōgen 法眼 (Hogen). Second highest. Lit. = seal of the law.

- Hokkyō 法橋 (Hokkyo). Third highest. Lit. = bridge of the law.

Note: These three ranks equated with the general ranking system among the Buddhist clergy, a system known as Sōkan 僧官 or Sōi 僧位. For details, see Sōi below.

Ho-in, Hoin 法印 (Hō-in, Hōin). Literally “Eye of the Law.” The highest rank awarded to Buddhist sculptors. See Hogen above for more details on ranks and titles.

Hokei (Hōkei) 宝髻 or 寶髻. The topknot of hair on sculpted images. Various types of topknots were developed over the centuries, and a knowledge of these topknot styles can help art historians in dating the statue. Most commonly found on images of the Bosatsu 菩薩 (Bodhisattva) and the Tenbu 天部 (Deva), but images of Dainichi Nyorai 大日如来 are sometimes depicted with topknots. The various styles are:

- Tankei 単髻 = Hair tied into one topknot

- Sokei (Sōkei) 双髻 = Hair divided into two parts

- Kokei (Kōkei) 高髻 = Single, high topknot that came to prominence in the Nara period. In another competing style, adopted from Tang China, the hair strands were wrapped like ribbons around the topknot, one above the other. (Example: Ashura statue at Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 in Nara.) In the subsequent Heian era, the hanging hairstyle (Suihotsu 垂髪) became most popular, but the Kokei high topknot regained favor again in the Kamakura period.

- Mage 髷 = Chignon. A topknot associated especially with Monju Bosatsu 文殊菩薩, one that rose to prominence with the emergence of the Shingon 真言 and Tendai 天台 sects of Esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō 密教) in the Heian period. Monju is frequently represented with five curls or knots (chignons) of hair, indicating the five-terraced mountain (Ch. = Wutaishan) in China where Monju is venerated, or the five kinds of wisdom important to the Shingon sect, which in turn relates to the five elements of earth, water, fire, air (wind), and space (ether). There are other forms of Monju as well, those based on the number of hair knots (one, five, six, or eight), with each form providing protection against different dangers. The specific Japanese term for a knot of five round bunches is Gokei 五髻.

- Suihotsu 垂髪. Hanging hairstyles that became very popular in the Heian era.

Hokkyo 法橋 (Hokkyō or Hōkyō). Literally “Bridge of the Law.” The third highest rank awarded to Buddhist sculptors. See Hogen above for more details on ranks and titles. It is thought that the acclaimed Heian-era sculptor Jocho was the first to receive the rank of Hokkyo for his work at Hojoji Temple 法成寺 (Hōjōji, Houjouji). Founded in +1020 by Fujiwara-no-Michinaga, the father of Fujiwara-no-Yorimichi, the temple is no longer standing. It was lost around the 14th century.

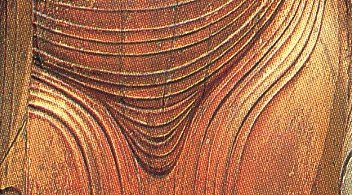

Honpashiki Emon 翻波式衣文. Also spelled Hompa-Shiki. Literally the "Rolling Wave Style of Drapery Folds." A carving style that gained prominence in the Early Heian Period (+794-894). Honpa-shiki featured an alternating series of wide and narrow (or high and low, large and small) folds that flowed down the garment in evenly spaced and regular patterns, like waves breaking on the beach. The style became popular and remained in use into modern times. It has a close cousin, called the Rippling Wave Style. Additionally, the Rolling Wave technique was considered a hallmark feature of the Jōgan Style of Buddhist statuary, so-called because it emerged during the Jōgan Period 貞観 (+794-894). The objective was not to create realistic folds, but rather to achieve a melodious, undulating and rhythmic beauty. Visit the Drapery page for more photos and details.

Early Heain Era, Rolling Wave Drapery

In School or Inpa School 院派. A powerful group of Kyoto-based sculptors who sprang from the workshop of Jocho. Most artists of this school used the character IN 院 in their names, hence the school is named Inpa (pa 派, also pronounced ha, is the character for “school” or faction.) The Inpa school created refined and elegant statuary for the court and nobility in Kyoto, and essentially monoplized the patronage of the imperial court along with their rival, the Enpa School, in the second half of the Heian period. The two schools are collectively known as the Kyoto Busshi, since their main workshops were located in Kyoto. The principal workshops of the Inpa School were at Shichijo Oomiya Bussho 七条大宮仏所 (Shichijō) and at Rokujo Madenokoji Bussho 六条万里小路仏所 (Rokujō Madenokōji Bussho), both in Kyoto. See the Heian-era page for many more details on the Inpa School and reviews of its main artists.

Iwabuchi Dera 石淵寺. Location of a famous bronze workshop in the Nara period. Says Ernest F. Fenollosa in his book Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art (ISBN 4-025080-29-6): “There was a large stock of images from India, China, and Korea already in Japan, which the Japanese used as models for their own budding sculptural genius. The art of the age is a continual recasting in a long series of trial forms of the elements involved in this stock. The chief advance is found in the series of bronze statuettes which were manufactured for the alter-pieces of the many Buddhist temples that now spread all over Yamato. Hokkeiji and Horinji were sites not far from Horyuju Temple. There is a persistent Nara tradition that at one of the many temples then flourishing near the capital, one called Iwabuchi-dera 石淵寺, a special school of bronze statuette modelling and casting was instituted. However that may be, the time is marked by an effort to discard the clumsier weaker earlier models and aim instead to achieve a more human grace and spiritual sweetness, with the draperies becoming more natural and simple. <end quote by Fenollosa>

Jochoyo 定朝様 (Jōchōyō). Literally “in the style of Jocho,” the acclaimed Heian-era sculpture from whose workshop sprang three of Japan’s most famous schools of sculpture.

Jogan Style 貞観 (Jōgan). A style of Buddhist sculpture that emerged in the early Heian period, so-called because it appeared during Japan’s Jōgan Period 貞観 (+794-894). One of the hallmark features of the Jogan style was Honpashiki folds (rolling waves) in the drapery, achieved by carving alternating series of small and large folds. Other features included fleshy, heavier, more massive bodies, rounder faces, and wider eyes and noses.

Kei School or Keiha School 慶派. The Kei school is also known as the Nara Busshi 奈良仏師, for their main workshop was located at Kofukuji Temple (Kōfukuji 興福寺) in Nara. Like the Enpa and Inpa schools, the Kei school sprang from the statuary workshop of acclaimed sculptor Jocho. Kei artists created a new style of statuary. In contrast to the refined and delicate work of their rivals, the Kei school carved passionate, powerful, and robust statuary that better suited the tastes of the new military classes, who scorned the perfumed embroidery of the court and aristocracy. Two sculptors in particular came to embody the new Kamakura style of dynamic and realistic statuary -- Unkei and Kaikei. The Kei school dominated Japanese Buddhist statuary in the 13th and 14th centuries. Since most artists of this school used the character KEI 慶 in their names, their school was known as the Keiha (ha 派 is the character for “school” or faction.) See the Kamakura-era page for many more details on the Keiha and reviews of its main sculptors.

Kibusshi 木仏師. Literally “sculptor of wood Buddha statues.” The term first appeared in the Heian period (9th century onward), by which time wooden sculpture had gained dominance over bronze, lacquer, & clay statuary. In the earlier Asuka and Nara periods (until the end of the 8th century), Buddhist sculptors were called Busshi 仏師. But when wood achieved dominance in the Heian period, Kibusshi became the general term for all sculpting artists.

Kofukuji (Kōfukuji) Temple 興福寺 in Nara. The workshop headquarters of the Keiha School of Buddhist Sculptors, who dominated the world of Japanese Buddhist statuary in the 13th and 14th century. Since their main workshop at Kofukuji was in Nara, they are known as the Nara Busshi. The workshop was first established by Raijo in the early 11th century. See Nara Busshi for more details. Kofukuji Temple was also the clan temple of the powerful Fujiwara 藤原 family.

Kyoto Busshi or Kyobusshi 京仏師 (Kyōto Busshi, Kyōbusshi). During the Heian Period, when the capital was located in Kyoto, two schools in particular gained the patronage of the court, nobility, and temples -- the Enpa School 円派 and the Inpa School 院派, both originating from a single founder, Jocho 定朝 (d. 1057), the father of Japan’s three most important schools of Japanese Buddhist sculpture. The third school was the Keiha School 慶派, whose main workshop was at Kofukuji Temple in Nara. The Enpa and Inpa schools are collectively known as the Kyoto Busshi 京都仏師 (literally “Kyoto sculptors”), while the Keiha school is known as the Nara Busshi. Although these three schools were rivals, there was nonetheless considerable collaboration among them. The Kyoto-based Enpa and Inpa sculptors dominated the world of Japanese sculpture during the 11th and 12th centuries (Heian 平安 Period, Fujiwara 藤原 period), but they were overshadowed by the Keiha 慶派 in the Kamakura period (+1185-1332).

Machi Busshi 町仏師. Town sculptors. Says Patricia J. Graham: “Outside formal busshi ateliers, beginning in the 16th century independent groups of lay Buddhist ‘town sculptors’ (machi busshi) formed their own workshops to compete with the prestigious orthodox ateliers. Although they remain largely obscure, one representative early group, the Nara-based Shukuin Busshi, has been the subject of recent scholarly study.” <end quote, p. 132-133>

Nanto Busshi 南都仏師 or Nara Busshi 奈良仏師. Literally “Busshi of the South.” A general term for Buddhist sculptors working in Nara during and after the Kamakura period (13th to 14th centuries). Nara is considered the southern capital, Kyoto the nothern capital, but by this time political power was held by the military government much further north in Kamakura and the Kanto region. Several schools of Nanto Busshi were particularly important in the Muromachi period. The origins of the Nanto Busshi goes back to the time of Kakujo 覚助 (d. 1077), the son and successor of famed sculptor Jōchō (d. 1057). From their loins sprang the celebrated Nanto Busshi of the Keiha School 慶派 of sculptors, based originally at Kōfukuji Temple 興福寺 in Nara. Their most renowned artists were Unkei 運慶 (d. 1223) and Kaikei 快慶 (d. 1226). An innovative branch of the Keiha School known as the Zenpa School 善派 (closely associated with Saidaiji Temple 西大寺 in Nara) also emerged in the Kamakura period (13th century). This was followed by the emergence of the Nanto Busshi schools known as Tsubai Bussho 椿井仏所 in the 14th century, and then the Takama Bussho 高間仏所 and Shukuin Bussho 宿院仏師. The latter two were most active in the 15th and 16th centuries. Other schools set up in the mid-to-late 14th centuries include the Nobori-Ōji Bussho 登大路仏所 and Fujiyama Bussho 富士山仏所. Most of these schools / workshops survived into the Edo Period (1615-1868). For more details, see JAANUS Entry 1 and JAANUS Entry 2.

Nara Busshi 奈良仏師 or Nanto Busshi 南都仏師. Nara-related Buddhist sculptors. Nanto Busshi literally means “Busshi of the Southern Capital,” since Nara is located to the south of Kyoto (the Northern Capital). It refers specifically to those associated with the workshop established by Kakujo 覚助 (d. +1077) in Kyoto and another by his son Raijo 頼助 in Nara. Kakujo’s workshop was known as Shichijo Bussho 七条仏所 (Shichijō Bussho) for it was located in the Shichijo Takakura 七条高倉 (Shichijō Takakura) district of Kyoto, and it remained active until the Edo Period. See below for more on Shichijo. His son Raijo was not content in Kyoto, for two other powerful Busshi groups (the Enpa School 円派 and the Inpa School 院派 had a near-monopoly on statue production and court patronage. These schools all sprang from the workshop of the acclaimed Jocho 定朝 (d. +1057), who was Kakujo’s father and Raijo’s grandfather. Raijo established his workshop at Kofukuji Temple 興福寺 (Kōfukuji) in Nara, which over time became the main headquarters of the Keiha School 慶派. Raijo’s decision to move to Nara was a wise one, for he and his lineage quickly gained the support of the influential Fujiwara 藤原 clan located in Nara. By the Kamakura period, the Keiha School dominated the making of Buddhist statues thanks to the patronage of the Kamakura government and the dynamic and powerful art of Unkei and his workshop. For many more details on the Nara Busshi, plus reviews of its sculptors, please see the Kamakura-era page.

Nobori-ooji Bussho 登大路仏所. An offshoot of the Tsubai Bussho 椿井仏所. Thought to have emerged sometime in the 15th century but subsequently declined in the 16th century.

Renpashiki Emon 漣波式衣文. Also spelled Rempa-Shiki. Literally the "Rippling Wave Style of Drapery Folds." It appeared in the early-to-mid Heian era, with some saying it represents the fancier version of the Honpashiki Rolling Wave style. The Rippling Wave style comes in two basic types: (1) a regular alternating pattern of two low-ridged curves followed by one high curve or as (2) an unbroken series of narrow and low curves. It has a close cousin, called the Rolling Wave Style. Visit the Drapery page for more photos and details.

Mid-Heain Era. Renpa Shiki. Rippling Wave Drapery

Rokujo Madenokoji Bussho 六条万里小路仏所 (Rokujō Madenokōji). A workshop making Buddhist sculpture located in Kyoto between the 11th and 14th centuries. Established by Incho 院朝, a major sculptor of the Inpa School in Kyoto during the 12th century. Rokujo Madenokoji was thus a branch workshop of the Inpa school, but its fortunes declined gradually in the Kamakura period with the rise to prominence of the Keiha school.

Sanjo Bussho 三条仏所 (Sanjō). A Kyoto workshop, apparently set up by Jocho’s apprentices Chosei 長勢 (d. +1091) and Ensei 円勢 (d. +1134), and known to have existed at least by the time of Myoen 明円 (d. +1199). It is thus a workshop of the Enpa School. See the Heian-era page for many more details on the Enpa School, and reviews of its main sculptors and workshops.

Shichijo Bussho 七条仏所 (Shichijō, literally “Seventh Avenue”). A Kyoto workshop established by Kakujo 覚助 (d. +1077), the son and successor of Jocho. Kakujo established his Shichijo Bussho workshop in Kyoto's Shichijo Takakura 七条高倉 area. The workshop remained active from the late 12th century into the 19th century, and served as an important workshop for Keiha artists. Unkei, the undisputed champion of Kamakura sculpture, moved to Kyoto in the latter half of his life, establishing a workshop in the same area. Other Kei artists established workshops in this district of Kyoto as well, thus the Keiha school of sculptors is also referred to as the Shichijō School. As a group, they were superceded by other groups after the mid-17th century owing to the mounting financial difficulties of their main patrons (wealthy & powerful samurai).

Says JAANUS: A Buddhist sculpture workshop (bussho 仏所) located in Kyoto's Shichijou Takakura 七条高倉, which was founded by Jouchou's 定朝 (d. 1057) son Kakujo 覚助 and active from the late Fujiwara period (12c) until the Edo period (17-19c). Kakujo was followed by Koukei 康慶, Unkei 運慶 (d. 1223), and his sons, who formed the Keiha 慶派 school of sculptors. They worked in shichijou bussho, as well as in their headquarters in Nara Koufukuji 興福寺. Sources disagree about which workshop was set up first, but shichijou bussho is considered a branch of the Keiha school, and the term shichijou bussho is occasionally used to refer to the Keiha in general. Examples of shichijou bussho work include the famous central Senju Kannon 千手観音 (1254) and 10 of the standing Kannon figures in Kyoto's Renge-oin 蓮華王院 (Sanjuusangendou 三十三間堂), made by Unkei's son Tankei 湛慶 (1173-1256). Several members of Shichijo-bussho formed separate workshops, which are in a broad sense considered to be part of the same school. Important branch schools include: shichijou nishi bussho 七条西仏所 established by Unkei's grandson Kouyo 康誉 in the 14c; shichijou naka bussho 七条中仏所, established in the 13c by Unkei's third son Kouben 康弁; and shichijou higashi bussho 七条東仏所 established in the 14c by Koushun 康俊 , son of Unkei's sixth son Unjo 運助 . <end quote>

Shichijo Oomiya Bussho 七条大宮仏所 (Shichijō Oomiya). A Kyoto workshop making Buddhist sculpture between the 11th and 14th centuries. Established by Injo 院助 (d. +1108), the gifted apprentice of Jocho's son Kakujo 覚助 (d. +1077), it became the most important workshop of Japan’s Inpa School 院派 of Buddhist statuary. Its fortunes declined gradually in the Kamakura period with the rise to prominence of the Keiha school.

Shobusshi 小仏師 (Shōbusshi). Also spelled 少仏師. A team of Buddhist sculptors and artisans under the control of a master sculptor (Daibusshi 大仏師). By the 10th century, the introduction of new techniques for making large wooden statues (see Making Buddhist Statues) sparked demand and increased the number and size of commissions from the court and nobility. Numerous independent workshops (Bussho 仏所) were set up, with some employing hundreds of assistants. The new production methods also fueled a division of labor among the artisans (the Shobusshi) into fields such as wood carving, metal casting, painting, jewelry making, and gilding. Shobusshi 小仏師 (Shōbusshi). Also spelled 少仏師. A team of Buddhist sculptors and artisans under the control of a master sculptor (Daibusshi 大仏師). By the 10th century, the introduction of new techniques for making large wooden statues (see Making Buddhist Statues) sparked demand and increased the number and size of commissions from the court and nobility. Numerous independent workshops (Bussho 仏所) were set up, with some employing hundreds of assistants. The new production methods also fueled a division of labor among the artisans (the Shobusshi) into fields such as wood carving, metal casting, painting, jewelry making, and gilding.

Shukuin Busshi 宿院仏師 and Shukuin Bussho 宿院仏所. Sculptors of the Nara area active in the 15th and 16th centuries (see Muromachi period). Came to prominence in the 16th century and prospered for some 80 years. Main workshop was called Shukuin Bussho 宿院仏所 (aka Shukuin Bussho-ya 宿院仏所屋), for they came from a location in Nara known as Shukuin 宿院. They are loosely considered part of the Nanto Busshi 南都仏師. They were originally carpenters (Jp. = Tōryō 棟梁, Toryo) and wood craftsmen (Kiyose Banshō 木寄番匠), but they ultimately became makers of Buddhist statuary. Shukuin was one of the first Bussho (workshops) where sculptors worked as laypeople without assuming the status of monks or without joining the monastic orders. See Sculptors of the Muromachi Era to learn more about their artists. Many made wooden statues, often commissioned by small temples in the Nara area (e.g., Shaka 釈迦 and Yakushi 薬師 figures at Higashida Yakushidō 東田薬師堂). Other similar commercial workshops were active in the Edo Period (1615-1868), and the bussho system itself survived until the 19th century. The bussho model is credited to Jōchō (d. 1057). For more details, see this J-site. Also see JAANUS (outside link) for list of important Shukuin artists. <Need to add quote pp. 132-133 of Graham book> Shukuin Busshi 宿院仏師 and Shukuin Bussho 宿院仏所. Sculptors of the Nara area active in the 15th and 16th centuries (see Muromachi period). Came to prominence in the 16th century and prospered for some 80 years. Main workshop was called Shukuin Bussho 宿院仏所 (aka Shukuin Bussho-ya 宿院仏所屋), for they came from a location in Nara known as Shukuin 宿院. They are loosely considered part of the Nanto Busshi 南都仏師. They were originally carpenters (Jp. = Tōryō 棟梁, Toryo) and wood craftsmen (Kiyose Banshō 木寄番匠), but they ultimately became makers of Buddhist statuary. Shukuin was one of the first Bussho (workshops) where sculptors worked as laypeople without assuming the status of monks or without joining the monastic orders. See Sculptors of the Muromachi Era to learn more about their artists. Many made wooden statues, often commissioned by small temples in the Nara area (e.g., Shaka 釈迦 and Yakushi 薬師 figures at Higashida Yakushidō 東田薬師堂). Other similar commercial workshops were active in the Edo Period (1615-1868), and the bussho system itself survived until the 19th century. The bussho model is credited to Jōchō (d. 1057). For more details, see this J-site. Also see JAANUS (outside link) for list of important Shukuin artists. <Need to add quote pp. 132-133 of Graham book>

Soi or So-i 僧位 (Sōi, Sō-i). A system for bestowing rank and title upon men and women in the Buddhist clergy who were also great scholars. A similar ranking system was later applied to distinquished Buddhist sculptors, and then later still, applied to writers, artists, warriors, and other lay people who made great contributions to their fields of study. See Hogen above for more details on ranks and titles of non-clergy Buddhist sculptors. The first supervisory system for regulating the relationship between the state and clergy was set up in +624 by Empress Suiko 推古 (reigned + 592 to 628). Called the Sōgō-sei 僧綱制 system, the Sōgō system was also charged with the discipline and punishment of monks and nuns. The three ranks were:

- Sojo 僧正 (Sōjō); Highest rank among clergy

- Sozu 僧都 (Sōzu); Second highest rank

- Risshi 律師; Third highest; known formerly as Hōzu or Hōtō 法頭

Later, during the reign of Emperor Jun’nin 淳仁 (reigned 758 -764), five clerical ranks were established that corresponded, respectively, to court ranks from three to seven. The ranks were, from high to low:

- Dentō Daihōshi-i 傳燈大法師位

Rank of the Great Master of Transmission of Light

- Dentō Hōshi-i 傳燈大法師位

Rank of the Master of Transmission of Light

- Dentō Man-i 傳燈満位, Senior Rank of Transmission of Light

- Dentō Jū-i 傳燈住位, Junior Rank of Transmission of Light

- Dentō Nyū-i 傳燈入位, Initiatory Rank of Transmission of Light

- Note: As translated by Kyoko Motomochi Nakamura in "Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition, p. 3; the ranks appear in the Shoku Nihongi 続日本紀.

Takama Bussho 高間仏所 or Takaya Bussho 高矢仏所. Buddhist sculptors of the Nara area active in the 15th and 16th centuries (see Muromachi period). This guild from Nara was a branch of the Tsubai Bussho 椿井仏所. Its most acclaimed sculptor was Kōson (Koson) 弘尊 of the 15th century, who had worked with Shunkei 春慶, an important sculptor of the Tsubai Bussho.

Tori School or Toriha 止利派. The most widely acclaimed sculptor in the Asuka period (the early years of Buddhism in Japan) was Kuratsukuri no Tori 鞍作止利, more properly known as Tori Busshi. His work and that of his apprentices came to epitomize the artistic style of the period. Bronze ruled the roost, greatly overshadowing wood statuary.

Tori Yoshiki 止利様式 (Yōshiki). Sometimes written Tori Shiki 止利式. A sculptural style associated with the acclaimed 7th-century sculptor Kuratsukuri no Tori 鞍作止利, who is more commonly known as Tori Busshi 止利仏師. The work of this artist and his pupils came to epitomize the art of the 7th century. Tori Yoshiki literally means “Tori Style.” See Asuka Era for details.

Tsubai Bussho 椿井仏所. Also written 津波井仏所. Guild of Buddhist sculptors active in Nara from the mid-14th to 16th century, named after their location at Kōfukuji Tsubaigō 興福寺椿井郷 in Nara. It is believed the workshop was established by Keiha artists. In the 15th century, the Takama Bussho 高間仏所, Nobori-Ōji Bussho 登大路仏所, and Fujiyama Bussho 富士山仏所 all apparently emerged as offshoots of Tsubai Bussho, but all declined during the 16th century, when the Shuku-in Bussho 宿院仏所 became dominant. The most celebrated sculptors of the Tsubai Bussho are Kankei 覚慶, Keishū 慶秀, Shunkei 舜慶, and Shunkei 春慶. The Kishi Monju Bosatsu 文殊菩薩 statue (1378) at Jōdoji Temple 浄土寺 in Hiroshima prefecture bears the inscription Nanto Tsubai-saku 南都津波居作, giving testiment to the activities of this workshop. Others include Jōkeiin 成慶, Seikei 清慶, Shūkei 集慶, 椿井丹波公, 椿井次郎, and 椿井式部ら.<Source: JAANUS>

Tsubai artists continued carving statues into the Edo period, but on a much reduced scale year after year. Various other workshops sprang from the Tsubai Bussho, including the Osaka-based Tsubai Minbu Bussho 椿井民部仏所, which was active in the 17th century on the repair and replacement of statuary at the reconstructed Nara Daibutsuden. Two of its prominent sculptors were Tsubai Minbu Kenkei and Tsubai Minbu Inkei. <Patricia J. Graham>

Wayo 和様 (Wayō). Literally “Japanese Style” sculpture as opposed to Chinese-style statuary. Admired for its gentleness and simplicity, the Wayo style is associated with the work of acclaimed Heian-era sculptor Jocho (d. +1057), whose art is generally regarded as the pinnacle of the Wayo style. In addition, Japan's break with China in the 9th century provided an opportunity for a truly native Japanese culture (Kokufū Bunka 国風文化) to flower, and from this point forward indigenous secular art becomes increasingly important. See Fujiwara Style for a few more details.

Zen School or Zenpa School 善派. An innovative branch of the Keiha School that appeared in the Kamakura era. Most artists of this school used the character ZEN 善 in their names, hence the school is named Zenpa (pa 派, also pronounced ha, is the character for “school” or faction.) The character for Zen 善 used by the Zenpa school is not the same character used by the Zen 禅 sects of Buddhism. Thus, no association should be made between the Zenpa school of sculptors and the Zen sects of Buddhism.

Zobussho 造仏所 (Zōbussho) and Todaiji Zobussho 東大寺造仏所 (Tōdaiji Zōbussho). Government-sponsored workshops for making Buddhist statues. Established in the 7th century in the Nara area. Each Busshi 仏師 (sculptor) was affiliated with a workshop. Lavish court spending during the period resulted in numerous commissions, with various types of artisans hired for different tasks, including those who specialized in carving wood, painting, casting metal, making jewelry, and other fields. By the late 8th century, the state-sponsored Zobussho were shut down and replaced by independent or temple-run workshops called Bussho 仏所. One of the most important Zobussho was located at Todaiji Temple 東大寺 (Tōdaiji) in Nara, one of the Seven Great Nara Temples and home to the Great Buddha (Daibutsu) statue of Nara. The Todaiji workshop was known as Zo Todaiji Zobussho 造東大寺造仏所 (Zō Tōdaiji Zōbussho) or as Todaiji Zobussho 東大寺造仏所 (Tōdaiji Zōbussho). It was active from +748 to 789, and at one time employed over 1600 sculptors. Once the project was completed, the Todaiji Zobussho was closed, marking the end of government-sponsored workshops. The sculptors who worked at Todaiji dispersed, some setting up private workshops and others pursuing work at Nara’s many temples. For more details, see the following JAANUS pages: Zoubussho and Zou Toudaiji Bussho. The JAANUS pages cover numerous other keywords, including:

- Betto (Bettō 別当); administrative or technical director

- Shoryo (Shōryō 将領); administrative deputy

- Chojo (Chōjō 長上); technical deputy

- Zakko (Zakkō 雑工); skilled sculptors

- Jicho (Jichō 仕丁); errand boys

- Kobu 雇夫 (laborers)

- Satojin 里人 (independent sculptors)

- Shiko (Shikō 司工); permanent employees

- See JAANUS Zobussho or Zou Toudaiji Bussho for details

ENGLISH & JAPANESE RESOURCES

- Numerous Japanese-language museum and temple catalogs, magazines, books, and web sites. See Japanese Bibliography for complete list.

- Numerous English-language museum and temple catalogs, magazines, books, and web sites. See English Bibliography for complete list.

- JAANUS. Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System. In my mind, JAANUS is the best online database available on Japanese art history. Compiled by the late Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent, it covers both Buddhist and Shinto deities in great detail and contains over 8,000 entries.

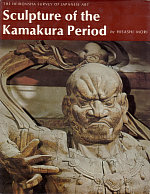

Heibonsha, Sculpture of the Kamakura Period. By Hisashi Mori, from the Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art. Published jointly by Heibonsha (Tokyo) & John Weatherhill Inc. A book close to my heart, this publication devotes much time to the artists who created the sculptural treasures of the Kamakura era, including Unkei, Tankei, Kokei, Kaikei, and many more. Highly recommended. 1st Edition 1974. ISBN 0-8348-1017-4. Buy at Amazon Heibonsha, Sculpture of the Kamakura Period. By Hisashi Mori, from the Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art. Published jointly by Heibonsha (Tokyo) & John Weatherhill Inc. A book close to my heart, this publication devotes much time to the artists who created the sculptural treasures of the Kamakura era, including Unkei, Tankei, Kokei, Kaikei, and many more. Highly recommended. 1st Edition 1974. ISBN 0-8348-1017-4. Buy at Amazon . .

- Classic Buddhist Sculpture: The Tempyo Period. By author Jiro Sugiyama, translated by Samuel Crowell Morse. Published in 1982 by Kodansha International. 230 pages and 170 photos. English text devoted to Japan’s Asuka through Early Heian periods and the development of Buddhist sculpture during that time. ISBN-10: 0870115294. Buy at Amazon.

The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture, AD 600-1300. By Nishikawa Kyotaro and Emily J Sano, Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth) and Japan House Gallery, 1982. 50+ photos and a wonderfully written overview of each period. Includes handy section on techniques used to make the statues. The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture (AD 300 - 1300) The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture, AD 600-1300. By Nishikawa Kyotaro and Emily J Sano, Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth) and Japan House Gallery, 1982. 50+ photos and a wonderfully written overview of each period. Includes handy section on techniques used to make the statues. The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture (AD 300 - 1300) . .

Introduction & Index to Japanese Buddhist Sculptors (Busshi)

Asuka | Hakuho | Nara | Heian | Kamakura | Muromachi | Edo | Modern

Busshi Glossary | Jocho Busshi | Unkei Busshi | Kaikei Busshi

Contemporary Busshi Mukoyoshi Yūboku & Nakamura Keiboku

|