|

|

Built in 1984

Bronze, 21.35 meters

MODERN

CHRONOLOGY

Meiji Period

明治時代 +1868-1912

Taisho (Taishō) Period

大正時代 +1912-1925

Showa (Shōwa) Period

昭和時代 +1926-1989

Heisei Period

平成 (+1989 to today)

|

|

HISTORICAL SETTING. Japan’s rapid modernization and industrialization, and its subsequent colonialization of greater Asia, brought it into direct conflict with Western powers. The result was World War Two, perhaps the most deadly and destructive war in earth history. Japan surrendered soon after the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Its lands were occupied by American forces, its military dismantled, a new constitution imposed by the victors, and the task of rebuilding the nation begun in earnest. The emperor was stripped of all political power and forced to renounce his divine godlike status, although he retained his role as figurehead of the nation. From the 1950s into the 1990s, Japan experieced its so-called Postwar Economic Miracle -- today it is the world’s second largest economy.

Rescuing Japan’s Folk Art (Mingei)

Japan’s rapid pre-war industrialization was accompanied by a massive effort to learn, import, and adapt Western science, technology, and art. But modernization had its costs, for many of Japan’s traditional art forms were quickly overcome by the new fascination with Western forms. Yanagi Soetsu 柳宗悦 (+1889-1961) lamented this development, and coined the term Mingei 民芸 (folk art) in 1926 to refer to common crafts that had been brushed aside by the industrial revolution. Yanagi and his lifelong companions, the potters Bernard Leach, Hamada Shoji 濱田庄司, and Kawai Kanjiro 河井寬次郎, sought to counteract the desire for cheap mass-produced products by pointing to the works of ordinary crafts people that spoke to the spiritual and practical needs of life.

The Mingei Movement sparked by Yanagi was responsible for keeping alive many traditions. Yanagi also founded the Japan Folk Craft Museum (Nihon Mingeikan 日本民芸館) in 1936, which today houses approximately 17,000 items made by anonymous crafts people mainly from Japan, but also from China, Korea, and elsewhere.

Buddhism in Modern Japan. Institutionalized Buddhism never recovered from its setbacks in the Meiji era. It still survives, of course, but growth is stagnant. Its main functions are the performance of funeral and memorial services, the upkeep of the nation’s graveyards, and the sale of amulets and talismans to ward off illness and evil. The many extant temples (and their wonderful art treasures) also serve as living museums of Japan’s religious past, and attract millions of tourists each year. A small group of artists still practice Buddhist sculpting, but their ranks are dwindling. See Modern Busshi (Sculptors) for a review of these artists.

Modern Japanese Buddhism includes 13 traditional sects and nearly 100 sub-sects. Of the thirteen, three originated in the Asuka / Nara era, two in the Heian era, and virtually all the rest in the Kamakura period. The number thirteen is rather arbitrary, but follows a Buddhist tradition set earlier in China. Curiously, during Japan’s Meiji Restoration 明治維新 (late 19th century), the government officially recognized 13 Shinto sects outside its own state-sponsored shrines (the latter devoted to glorifying the emperor). This is surprising given the Meiji government’s anti-Buddhist policies.

13 Traditional Buddhist Sects (Era Originated)

- Kegon 華嚴宗 (Asuka/Nara)

- Hosso 法相宗 (Asuka/Nara)

- Ritsu 律宗 (Asuka/Nara)

- Tendai 天台宗 (Heian)

- Shingon 眞言宗; also Mikkyo 密教 (Heian)

- Zen Rinzai 臨濟宗 (Kamakura)

- Zen Soto 曹洞宗 (Kamakura)

- Zen Obaku 黄檗宗 (Kamakura)

- Pure Land (Jodo) 淨土宗 (Kamakura)

- Jodo Shin 眞宗 (Kamakura)

- Yuzu-nembutsu 融通念佛宗 (Kamakura)

- Ji 時宗 (Kamakura)

- Nichiren 日蓮宗 (Kamakura)

Note: Mikkyo 密教 = Esoteric Buddhism,

including both Shingon and Tendai

Note: Brief Overview of Buddhist NGOs in Japan, by Jonathan S. Watts, published by the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 31 / 2: 417–428, 2004, Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture

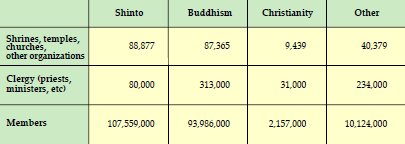

Statistics on Japan’s Religious Organizations

Source: Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, Dec. 31, 2003

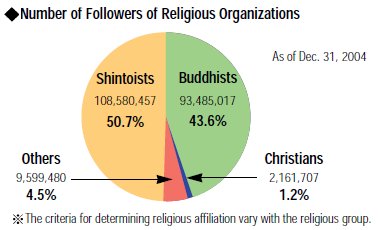

Source: Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, Dec. 31, 2004

According to government statistics, the number of religious groups in Japan at the end of 2003 were:

- Jōdo & Jōdo Shin = 30,000

- Zen = 21,000

- Shingon = 15,000

- Nichiren = 14,000

- Tendai = 5,000

- Shinto Shrines =88,877

- Christian Churches = 9,439

- Others (minimal)

Source: Japanese Ministry of Cultural Affairs

In 2003, over 300,000 Buddhist clergy attended to the needs of their flock, compared to around 80,000 Shinto clergy. Some 85% of Japan’s population claim to be Buddhists, with the largest group (around 25 million people) belonging to the Nichiren sect. However, the number of Japanese people claiming allegiance to either Shintoism or Buddhism exceeded 213 million, nearly 70% greater than Japan’s population of 127.5 million.

The Japanese obviously find no problem claiming simultaneous allegiance to both sides. This is easy to understand, for Shintoism and Buddhism flourished together (sharing deities and sacred grounds) for most of Japan’s recorded history. It was only in Japan’s Meiji Era (19th century) that the government forcibly separated the two camps, proclaiming Shinto to be the state religion (with the emperor a living god), and Buddhism to be a superstitious foreign import. Thankfully those militant days have passed. Modern Japan generally tolerates all faiths, and deities in the Shinto and Buddhist pantheons are worshipped again in tandem, as part of a unified set of protective spirits serving the nation.

Even so, the statistics are misleading. Since WWII, and the religious freedoms granted by Japan’s postwar constitution, the traditional Buddhist and Shinto sects have generated little enthusiasm among the people, and growth is stagnant. A recent survey by Zen’s Soto school found that nearly all people claiming a Buddhist affiliation could not name their sect's main temple or founder. Various government surveys reveal consistently that Japan’s population is indifferent to religion -- that the vast majority don’t practice Buddhism or Shintoism on any regular basis. Even though most families are affiliated with a Buddhist sect, this means little, for households were forced to declare an affiliation during the Edo era to help the government count the population and control tax registers. Most people visit shrines and temples as part of annual events and special rituals to commerate major life events, including the first shrine or temple visit of the new year (Hatsumode), the annual visit to the family grave during the Buddhist Festival (Obon) in August, the first shrine visit for a newborn baby (Miyamairi), the 7-5-3 (Shichi-Go-San) shrine festival for young children who attain those milestone ages, Shinto wedding ceremonies, and Buddhist funerals. Buddhism, moreover, is associated primarily with funerals and rituals for the dead, and most Japanese learn about Buddhism only after someone dies in their family. In Japan today, both Shinto and Buddhist practice among the common folk has taken on an air of "this-worldly benefits" (concrete rewards now; Jp. = 現世利益, Genze Riyaku). To many Japanese, Shinto and Buddhist faith is primarily involved with petitions and prayers for business profits, the safety of the household, success on school entrance exams, painless child birth, and other concrete rewards now, in this life.

Most Japanese homes still keep ancestral tablets (ihai 位牌) and altars (butsudan 仏壇) in their homes, which record the posthumous names of deceased family members and allow families to pay homage to their ancesters. Butsudan appeared in the private homes of Japan's aristocracy at an early date, and became widespread among upper-class families during Japan's Kamakura (+1185-1333) and Muromachi periods (+1392-1568). The placing of ancestral tablets inside the butsudan is generally considered a Confucian influence.

As in the past, Japan’s existing temples and shrines, and their monks and nuns, pay no taxes.

BELOW SECTION NOT FINISHED

GABI’S BUSSHI START PAGE

LIST OF CONTEMPORARY BUSSHI (Japanese Language)

Showa Daibutsu (Aomori) Showa Daibutsu (Aomori)

Dainichi Buddha Daibutsu

Bronze, H = 21.35 Meters

Weight = 220 tons

Built in 1984 (Showa 59), the Showa Daibutsu is a giant effigy of Dainichi Nyorai, the central deity of worship among Japan’s Shingon sect of Esoteric Buddhism. Located at Seiryuu-ji Temple (Blue-Green Dragon Temple) in Aomori City, the statue is taller than the Nara Daibutsu and Kamakura Daibutsu. The temple itself is new, with construction launched in 1982.

SEIRYUUJI TEMPLE

AOMORI CITY, AOMORI PREFECTURE

TEL: 017-726-2312

FAX: 017-726-2124

Takaoka Daibutsu Takaoka Daibutsu

Takaoka City

Toyama Prefecture

Abridged translation of

Yomiuri Shimbun Story

Sept. 23, 2004

This sitting image of the Buddha is 7.4 meters high. If the pedestal is included, the statue is 15.9 meters in height. The original burnt to the ground numerous times during its history. Construction on this particular reproduction began in 1907, and was completed in 1933. The ground beneath the statue gave way in 1980, sinking about 11 meters, so the statue was moved to its current location and repairs yet again undertaken. According to records, the first Big Buddha in Takaoka was built of wood in the Kamakura era, but has since been lost to fire.

Sitting Byakue Kannon

White-Robed Kannon

百尺観音

26.4 meters in height.

Fukushima Prefecture

Near Soma City, 相馬市、福島県

Sitting image of the Goddess of Mercy, carved into a stone cliff. Construction of the statue was begun in 1930 by Busshi Yoshiaki Ara 仏師荒嘉明 (あらよしあき).

Busshi is a Japanese term that literally means “Buddhist Teacher,” but it is used as an honorific title for those who carve Buddhist statues.

Monk Yoshioka, a local from the Soma area, died in 1963 at the age of 62 without having finished the statue. Work was continued by a 2nd-generation sculpture, who died in 1978 at the age of 53. Today, a 3rd-generation master sculptor named Mr. Yoshimichi continues work on the incomplete statue.

For more photos, please visit this J-Site. Scroll down that page to find the photos.

GABI HAS WRITTEN PAGES ON MODERN BUSSHI HERE:

OTHER IMPORTANT MODERN BUSSHI

According to JA.WIKIPEDIA

- 近代以降

- 高村光雲

- 松久朋琳

- 山崎祥琳

- 西村公朝 (Gabi’s favorite)

- 松本明慶

ENGLISH RESOURCES

- JAANUS. Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System. Online database devoted to Japanese art history. Compiled by the late Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent, it covers both Buddhist and Shintō deities in great detail and contains over 8,000 entries.

- Dr. Gabi Greve. See her page on Japanese Busshi. Gabi-san did most of the research and writing for the Edo Period through the Modern era. She is a regular site contributor, and maintains numerous informative web sites on topics from Haiku to Daruma. Many thanks Gabi-san !!!!

- Heibonsha, Sculpture of the Kamakura Period. By Hisashi Mori, from the Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art. Published jointly by Heibonsha (Tokyo) & John Weatherhill Inc. A book close to my heart, this publication devotes much time to the artists who created the sculptural treasures of the Kamakura era, including Unkei, Tankei, Kokei, Kaikei, and many more. Highly recommended. 1st Edition 1974. ISBN 0-8348-1017-4. Buy at Amazon

. .

- Classic Buddhist Sculpture: The Tempyo Period. By author Jiro Sugiyama, translated by Samuel Crowell Morse. Published in 1982 by Kodansha International. 230 pages and 170 photos. English text devoted to Japan’s Asuka through Early Heian periods and the development of Buddhist sculpture during that time. ISBN-10: 0870115294. Buy at Amazon.

- The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture, AD 600-1300. By Nishikawa Kyotaro and Emily J Sano, Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth) and Japan House Gallery, 1982. 50+ photos and a wonderfully written overview of each period. Includes handy section on techniques used to make the statues. The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture (AD 300 - 1300)

. .

- Comprehensive Dictionary of Japan's National Treasures. 国宝大事典 (西川 杏太郎). Published by Kodansha Ltd. 1985. 404 pages, hardcover, over 300 photos, mostly color, many full-page spreads. Japanese Language Only. ISBN 4-06-187822-0.

- Bosatsu on Clouds, Byōdō-in Temple. Catalog, May 2000. Published by Byōdō-in Temple. Produced by Askaen Inc. and Nissha Printing Co. Ltd. 56 pages, Japanese language (with small English essay). Over 50 photos, both color, B&W. Some photos at this site were scanned from this book. Of particular use when studying the life and work of Jōchō Busshi.

- Visions of the Pure Land: Treasures of Byōdō-in Temple. Catalog, 2000. Published by Asahi Shimbun. Artwork from Byōdō-in Temple. 228 pages, Japanese language with English index of works. Over 100 photos, color and B&W. Some photos at this site were scanned from this book. No longer in print. Of particular use when studying the life and work of Jōchō Busshi.

- Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art by Ernest F. Fenollosa, published by ICG Muse Inc. ISBN 4-925080-29-6. English. Originally published in 1912, but new edition in 2000. Highly recommended book on Buddhist sculpture in Japan. Although Fenollosa's views on art history are often discredited by modern art historians, this is still an excellent book on Buddhist sculpture in Japan.

- Numerous Japanese-language temple and museum catalogs, magazines, books, and web sites. See Japanese Bibliography for extended list. Also relied on Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺 (Horyuji) catalogs and Asuka Historical Museum.

JAPANESE WEB SITES JAPANESE WEB SITES

ONLINE STORE SELLING BUDDHA STATUES

Buddhist-Artwork.com, our sister site, launched in July 2006. This online store sells quality hand-carved wooden statues of many Buddhist deities, especially those carved for the Japanese market. It is aimed at art lovers, Buddhist practitioners, and laity alike. Just like this site (OnmarkProductions.com), it is not associated with any educational institution, private corporation, governmental agency, or religious group.

UNFINISHED RESEARCH

|