|

|

|

|

|

BUSSHI 仏師 OF JAPAN = SCULPTORS OF JAPAN BUSSHI 仏師 OF JAPAN = SCULPTORS OF JAPAN

Who Made Japan’s Buddha Statues?

Sculptors, Schools & Workshops

in Japanese Buddhist Statuary

Heian Era. Jōchō Busshi, Enpa & Inpa School.

Before starting, please see the Busshi Index. It provides an overview of Japan’s main sculptors (Busshi) and sculpting styles, a helpful A-to-Z Busshi Index, plus definitions for essential terms and concepts.

This section of our site includes 14 pages, covers 100+ sculptors, features 100+ photos, and provides the web’s first-ever integrated guidebook to Japan’s sculptors.

|

|

|

Heian Busshi

20+ Artists

Emergence of

Japanese-style

statuary, and the

introduction of

Esoteric Buddhism

RELATED PAGES

Jocho Feature Story

|

|

HISTORICAL SETTING. One of the most fruitful periods of Japanese Buddhism and Buddhist art. The period begins with the transfer of the capital from Nara to Kyoto, but the powerful Nara temples didn’t relocate, as one of the primary goals of the transfer was to distance the court from involvement by the Buddhist monasteries. The Heian era was a groundbreaking moment in Japanese Buddhism and Buddhist art, with two new sects introduced to the original Six Old Sects of Nara. These newcomers sparked a flowering in Japan's artistic genius, introduced mandala artwork to Japan, and brought the promise of salvation to the common people. The newcomers were the Tendai 天台 and Shingon 真言 sects, both originating in China, brought back from China to Japan by Japanese priests Saicho 最澄 (Saichō, +766-822, founder of Japan's Tendai sect) and Kukai 空海 (Kūkai, +774-835, founder of Japan's Shingon sect). Both had taken the dangerous sea journey to China to learn the teachings. Upon their return to Japan, both played monumental roles in the merger of Shinto-Buddhist beliefs and the emergence of Esoteric Buddhism (Jp. = 密教, Mikkyō, Mikkyo) and esoteric art, the latter exemplified by mandala paintings and statues of wrathful deities with multiple heads and arms. Religious pilgrimages were instituted during the mid-Heian era as well. Pilgrimages became a lasting practice thereafter. HISTORICAL SETTING. One of the most fruitful periods of Japanese Buddhism and Buddhist art. The period begins with the transfer of the capital from Nara to Kyoto, but the powerful Nara temples didn’t relocate, as one of the primary goals of the transfer was to distance the court from involvement by the Buddhist monasteries. The Heian era was a groundbreaking moment in Japanese Buddhism and Buddhist art, with two new sects introduced to the original Six Old Sects of Nara. These newcomers sparked a flowering in Japan's artistic genius, introduced mandala artwork to Japan, and brought the promise of salvation to the common people. The newcomers were the Tendai 天台 and Shingon 真言 sects, both originating in China, brought back from China to Japan by Japanese priests Saicho 最澄 (Saichō, +766-822, founder of Japan's Tendai sect) and Kukai 空海 (Kūkai, +774-835, founder of Japan's Shingon sect). Both had taken the dangerous sea journey to China to learn the teachings. Upon their return to Japan, both played monumental roles in the merger of Shinto-Buddhist beliefs and the emergence of Esoteric Buddhism (Jp. = 密教, Mikkyō, Mikkyo) and esoteric art, the latter exemplified by mandala paintings and statues of wrathful deities with multiple heads and arms. Religious pilgrimages were instituted during the mid-Heian era as well. Pilgrimages became a lasting practice thereafter.

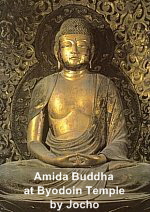

Japan’s break with China in the 9th century provided an opportunity for a truly native Japanese culture (Kokufū Bunka 国風文化) to flower, and from this point forward indigenous secular art becomes increasingly important. The great sculptural genius of the age was Jōchō (also see Special Page Devoted to Jōchō), whose statue workshop in Kyoto perfected the so-called Wayo 和様 (Wayō) style, which literally means “Japanese Style” statuary as distinct from Chinese-influenced images. Jocho and his pupils gained widespread support from the Japanese court, nobility, and temples for their cultivated and refined Buddhist carvings. The term “baroque” is also used for Heian era statuary, but it does not refer to Jocho’s elegant statuary -- rather, it refers to statues of the wrathful Esoteric deities, to the bold and plump statues with exaggerated forms and deep-cut drapery that also appeared during this time. Wood statuary rises to prominence in the Heian period, surpassing bronze thereafter as the main material for making religious statuary. The latter half of the Heian period is also commonly referred to as the Fujiwara 藤原 period, a time noted for the aristocratic tastes and ever-increasing luxury of the court in Kyoto. See Fujiwara Style for more. Japan’s break with China in the 9th century provided an opportunity for a truly native Japanese culture (Kokufū Bunka 国風文化) to flower, and from this point forward indigenous secular art becomes increasingly important. The great sculptural genius of the age was Jōchō (also see Special Page Devoted to Jōchō), whose statue workshop in Kyoto perfected the so-called Wayo 和様 (Wayō) style, which literally means “Japanese Style” statuary as distinct from Chinese-influenced images. Jocho and his pupils gained widespread support from the Japanese court, nobility, and temples for their cultivated and refined Buddhist carvings. The term “baroque” is also used for Heian era statuary, but it does not refer to Jocho’s elegant statuary -- rather, it refers to statues of the wrathful Esoteric deities, to the bold and plump statues with exaggerated forms and deep-cut drapery that also appeared during this time. Wood statuary rises to prominence in the Heian period, surpassing bronze thereafter as the main material for making religious statuary. The latter half of the Heian period is also commonly referred to as the Fujiwara 藤原 period, a time noted for the aristocratic tastes and ever-increasing luxury of the court in Kyoto. See Fujiwara Style for more.

JOCHO (JŌCHŌ) 定朝

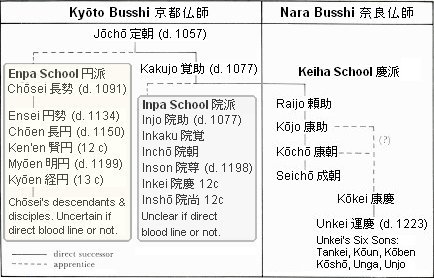

FATHER OF THREE SCHOOLS OF STATUARY. It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of Jocho 定朝 (Jōchō; d. +1057) to the world of Japanese Buddhist statuary. From his loins and workshop sprang three of the most important schools of Japanese Buddhist statuary -- the Enpa 円派, Inpa 院派, and Keiha 慶派 schools, which dominated Buddhist sculpture thereafter. Learn more about Jōchō at the:

JŌCHŌ PAGE

Special Page Devoted to Jōchō and His Statuary

HEIAN SCHOOLS OF STATUE MAKING

|

Note: Mori Hisashi, author of Sculpture of the Kamakura Period (ISBN 0-8348-1017-4), says the Enpa Line, from Chōsei through Myōen, are direct descendants; and the Inpa Line, from Injo through Inson, are also direct descendants. The above chart is based in part on one appearing in Mori’s book.

|

|

ENPA SCHOOL 円派. Also see above Lineage Chart. Founded by Chosei (Jocho’s pupil), this school created statues that appealed to the imperial family, upper classes, and the Kyoto (Kyōto) temples. Many sculptors of this school used the character 円 (EN) in their names, hence the school’s name ENPA (pa 派, also pronounced ha, is the character for "school" or faction.) The Enpa School’s main workshop was at Sanjo Bussho 三条仏所 (Sanjō Bussho) in Kyoto. Its main rival was the Inpa School of Buddhist statuary, another Kyoto-based workshop that likewise traces its origins to Jocho. Collectively the Enpa and Inpa schools were known as the Kyoto Busshi 京都仏師, and the two dominated Buddhist sculpture in the 11th and 12th centuries. Noted characteristics of the Enpa style were gentility and refinement, in the manner of Jocho before them. Over time, Enpa sculptors set up workshops in Fukushima, Kamakura, and other centers in outlying provinces. But its influence (and that of the Inpa school) declined precipitously in the 13th and 14th centuries when the new military government in Kamakura threw its support behind the Nara-based Keiha 慶派 School. The Enpa school remained active into the Muromachi period (+1392 - 1568), but it never regained its earlier prominence. Regretably, very few statues from Enpa artists have survived into modern times. Most were lost to natural disasters, temple fires, and the carnage of war. The school’s main artists were: ENPA SCHOOL 円派. Also see above Lineage Chart. Founded by Chosei (Jocho’s pupil), this school created statues that appealed to the imperial family, upper classes, and the Kyoto (Kyōto) temples. Many sculptors of this school used the character 円 (EN) in their names, hence the school’s name ENPA (pa 派, also pronounced ha, is the character for "school" or faction.) The Enpa School’s main workshop was at Sanjo Bussho 三条仏所 (Sanjō Bussho) in Kyoto. Its main rival was the Inpa School of Buddhist statuary, another Kyoto-based workshop that likewise traces its origins to Jocho. Collectively the Enpa and Inpa schools were known as the Kyoto Busshi 京都仏師, and the two dominated Buddhist sculpture in the 11th and 12th centuries. Noted characteristics of the Enpa style were gentility and refinement, in the manner of Jocho before them. Over time, Enpa sculptors set up workshops in Fukushima, Kamakura, and other centers in outlying provinces. But its influence (and that of the Inpa school) declined precipitously in the 13th and 14th centuries when the new military government in Kamakura threw its support behind the Nara-based Keiha 慶派 School. The Enpa school remained active into the Muromachi period (+1392 - 1568), but it never regained its earlier prominence. Regretably, very few statues from Enpa artists have survived into modern times. Most were lost to natural disasters, temple fires, and the carnage of war. The school’s main artists were:

Chosei 長勢 (Chōsei; +1010 - 1091). Chosei was Jocho’s pupil and the founder of the Enpa school of Buddhist statuary. Chosei established his workshop in Kyoto, where his desendants and disciples continued working after his death -- thus the Enpa School is also referred to as the Kyoto Busshi (or Kyobusshi), literally Kyoto-based sculptors, which also included a competing school of Kyoto sculptures called the Inpa School, also decended from Jocho. Extant work by Chosei includes wood statues of Nikkō Bosatsu 日光菩薩 and Gakkō Bosatsu 月光菩薩, plus life-size wood statues of the Jūni Shinshō 十二神将 (12 Heavenly Generals). Made around +1064, these statues are installed at Koryuji Temple 広隆寺 (Kōryūji) in Kyoto. Noted characteristics of his pieces are relatively small head sizes and poses suggesting slow yet deliberate motion. Chosei 長勢 (Chōsei; +1010 - 1091). Chosei was Jocho’s pupil and the founder of the Enpa school of Buddhist statuary. Chosei established his workshop in Kyoto, where his desendants and disciples continued working after his death -- thus the Enpa School is also referred to as the Kyoto Busshi (or Kyobusshi), literally Kyoto-based sculptors, which also included a competing school of Kyoto sculptures called the Inpa School, also decended from Jocho. Extant work by Chosei includes wood statues of Nikkō Bosatsu 日光菩薩 and Gakkō Bosatsu 月光菩薩, plus life-size wood statues of the Jūni Shinshō 十二神将 (12 Heavenly Generals). Made around +1064, these statues are installed at Koryuji Temple 広隆寺 (Kōryūji) in Kyoto. Noted characteristics of his pieces are relatively small head sizes and poses suggesting slow yet deliberate motion.

- Ensei 円勢 (d. 1134). One extant statue, only recently discovered at Ninna-ji Temple 仁和寺 in Kyoto. It is a seated sandalwood statue of Yakushi Buddha (薬師如来), approx. 24 cm in height from base to top of halo. It is a Secret Buddha 秘仏 (hibutsu), one kept hidden from the public by temple authorities. The temple allowed the Kyoto National Museum to inspect the statue in +1986, and the museum determined it was made around +1103 by Ensei and Choen. The statue was designated a National Treasure in 1990. Like Choen, Ensei was active at Kiyomizudera 清水寺 in Kyoto (his name appears in temple records), but sadly none of his work survived the passage of time.

Choen 長円 (Chōen; d. 1150). No extant work, except a small sandalwood statue of Yakushi Nyorai (薬師如来) only recently identified. See Ensei above for details. Choen at one time was the Betto 別当 (Bettō; term meaning “director”) of the temple workshop at Kiyomizudera 清水寺 in Kyoto. Unfortunately, even this lofty and influential position failed to ensure the survival of his art. Choen 長円 (Chōen; d. 1150). No extant work, except a small sandalwood statue of Yakushi Nyorai (薬師如来) only recently identified. See Ensei above for details. Choen at one time was the Betto 別当 (Bettō; term meaning “director”) of the temple workshop at Kiyomizudera 清水寺 in Kyoto. Unfortunately, even this lofty and influential position failed to ensure the survival of his art.

- Ken'en 賢円. Active in the middle 12th century. No extant work of definitive authorship. However, the Anrakujyuin Temple 安楽寿院 in Kyoto houses a wooden statue of a seated Amida Nyorai 阿弥陀如来 (approx. 87.6 cm in height). Made using the yoseki-zukuri 寄木造 technique (assembled-wood method) popular in those days. The statue is presumed to be the work of Ken'en.

- Myoen 明円 (Myōen; d. 1199). Extant pieces include the Five Great Mantra Kings (Godai Myōōzō 五大明王像) at Daikakuji Temple 大覚寺 in Kyoto, which are dated to around +1176. See photo at right, showing Kongōyasha 金剛夜叉, one of the five.

Kyoen 経円 (Kyōen). Active in the early 13th century. Extant pieces include a statue of Amida Nyorai 阿弥陀如来 at Kongōrinji Temple 金剛輪寺 (Tendai Sect) in Shiga prefecture, dated to approx. +1222-1226. Kyoen 経円 (Kyōen). Active in the early 13th century. Extant pieces include a statue of Amida Nyorai 阿弥陀如来 at Kongōrinji Temple 金剛輪寺 (Tendai Sect) in Shiga prefecture, dated to approx. +1222-1226.

- Ryuen 隆円 (Ryūen). Active in the middle 13th century. His genealogy is unknown. From +1251 to 1266, Ryuen and other Enpa sculptors worked alongside their counterparts from the Inpa and Keiha schools at Rengeoin (Rengeōin) Temple 蓮華王院 (Tendai Sect) in Kyoto. More commonly known as Sanjūsangendō (Sanjusangendo 三十三間堂), this temple contains 1,000 figures of the 1,000-Armed Kannon 千手観音 (Senju Kannon). The central figure was carved by Tankei (Unkei’s son), a member of the dominant Keiha School.

INPA SCHOOL 院派. Also see above Lineage Chart. The school’s name is easily explained -- most of the school’s members used the character IN (院) as part of their names, hence the name INPA (pa 派, also pronounced ha, is the character for "school" or faction). Like the rival Enpa 円派 and Keiha 慶派 schools, the Inpa school sprang from the workshop of Jocho 定朝 (d. +1057). Jocho’s son, Kakujo 覚助 (d. +1077), opened his own workshop in Kyoto, from which emerged his student Injo 院助, the founder of the Inpa school (who also became the adopted grandson of Jocho). The graceful and refined style of the Inpa school closely reflected the artistry of both Jocho’s and Kakujo’s workshops, and thus it suited the tastes of the Kyoto aristocracy. The Inpa workshop prospered, and dominated Buddhist sculpture in the late 12th century along with its rival, the Enpa 円派 School. But its fortunes declined in the subsequent Kamakura period when the Kamakura Shogunate threw its support behind the Nara-based Keiha 慶派 School. The Inpa and Enpa schools are known collectively as the Kyoto Busshi 京都仏師, for both were based in Kyoto. They received commissions largely from the imperial court and nobility, and their style became known as Wayo (Wayō 和様, or “Japanese style”). It represented Japan’s own indigenous art, featuring gentle and elegant features, extended eyebrows, smooth undulating robes, and most importantly, a preceived independence from Chinese influence. The Inpa’s most important workshops were Shichijo Oomiya Bussho 七条大宮仏所 (Shichijō Ōmiya) and Rokujo Madenokoji 六条万里小路仏所 (Rokujō Madenokōji) Bussho, both in Kyoto. Over time, Inpa artists established a presence in outlying provinces, but they never regained their earlier influence. INPA SCHOOL 院派. Also see above Lineage Chart. The school’s name is easily explained -- most of the school’s members used the character IN (院) as part of their names, hence the name INPA (pa 派, also pronounced ha, is the character for "school" or faction). Like the rival Enpa 円派 and Keiha 慶派 schools, the Inpa school sprang from the workshop of Jocho 定朝 (d. +1057). Jocho’s son, Kakujo 覚助 (d. +1077), opened his own workshop in Kyoto, from which emerged his student Injo 院助, the founder of the Inpa school (who also became the adopted grandson of Jocho). The graceful and refined style of the Inpa school closely reflected the artistry of both Jocho’s and Kakujo’s workshops, and thus it suited the tastes of the Kyoto aristocracy. The Inpa workshop prospered, and dominated Buddhist sculpture in the late 12th century along with its rival, the Enpa 円派 School. But its fortunes declined in the subsequent Kamakura period when the Kamakura Shogunate threw its support behind the Nara-based Keiha 慶派 School. The Inpa and Enpa schools are known collectively as the Kyoto Busshi 京都仏師, for both were based in Kyoto. They received commissions largely from the imperial court and nobility, and their style became known as Wayo (Wayō 和様, or “Japanese style”). It represented Japan’s own indigenous art, featuring gentle and elegant features, extended eyebrows, smooth undulating robes, and most importantly, a preceived independence from Chinese influence. The Inpa’s most important workshops were Shichijo Oomiya Bussho 七条大宮仏所 (Shichijō Ōmiya) and Rokujo Madenokoji 六条万里小路仏所 (Rokujō Madenokōji) Bussho, both in Kyoto. Over time, Inpa artists established a presence in outlying provinces, but they never regained their earlier influence.

- Injo 院助 (d. 1077). Founder of the Inpa School and Jocho's 定朝 adopted grandson. Awarded the highest rank of the Buddhist priesthood known as Hoin (Hōin or Houin 法印) although he was not a monk. No extant work to my knowledge.

Inkaku 院覚. Injo’s pupil, some say Injo’s son. Active in the mid-12th century. The wooden statue of Amida Nyorai 阿弥陀如来 (+1130) at Hokkongoin (Hōkkongōin) Temle 法金剛院 in Kyoto is attributed to Inkaku. It is approx. 2.2 meters in height. Inkaku 院覚. Injo’s pupil, some say Injo’s son. Active in the mid-12th century. The wooden statue of Amida Nyorai 阿弥陀如来 (+1130) at Hokkongoin (Hōkkongōin) Temle 法金剛院 in Kyoto is attributed to Inkaku. It is approx. 2.2 meters in height.

- Incho 院朝 (Inchō, Inchou). Injo’s pupil, some say Injo’s son. Active in the mid-12th century. Although he was not a monk, he was granted the highest rank of the Buddhist priesthood called Hoin (Hōin or Houin 法印). Extant pieces unknown.

- Inson 院尊 (+1120-1198). Active in the late 12th century, and a pupil of Inkaku or Incho or perhaps both. Unfortunately none of his work survives. However, he reportedly constructed the halo of the Great Buddha (Daibutsu 大仏) of Nara at Todaiji (Tōdaiji) Temple 東大寺, which was repaired after a fire in +1180. Although he was not a monk, he was granted the highest rank of the Buddhist priesthood (Hoin 法印) in the late 12th century. Already, by the 11th century, artists were awarded such lofty titles even though they had not joined the monastic orders. Among Inpa artists, Inson was perhaps the most eminent. For more on ranks and titles, click here.

- Injitsu 院実. Awarded the highest rank of the Buddhist priesthood known as Hoin (Hōin 法印) although he was not a monk. Extant pieces unknown.

Inkei 院慶. Active in the late 12th century. A pupil or son of Inkaku or Incho. A statue of Priest Koho (Kōhō) Ken'nichi 高峰顕日 (+1241-1316), enshrined at Kenchoji (Kenchōji) Temple 建長寺 in Kamakura, is attributed to Inkei. Inkei 院慶. Active in the late 12th century. A pupil or son of Inkaku or Incho. A statue of Priest Koho (Kōhō) Ken'nichi 高峰顕日 (+1241-1316), enshrined at Kenchoji (Kenchōji) Temple 建長寺 in Kamakura, is attributed to Inkei.

- Insho 院尚 (Inshō). Active in the late 12th century. A pupil or son of Inkaku or Incho. No extant work to my knowledge.

- Inpan 院範. Also spelled Impan. Active in the 13th century. A pupil of Inson. One of his pieces, an 11-headed Kannan (Jūichimen Kannon 十一面観音) at Hoshankuji (Hōshakuji) Temple 宝積寺 in Kyoto, is reportedly still extant. Temple authorities say it was made by either Inpan and In’un 院雲, another Inpa artist. Made around +1233, approximately 182.2 cm in height. Inpan was awarded the highest rank of the Buddhist priesthood in his lifetime, the Hoin (Hōin or Houin 法印) rank, although he was not a monk.

In’un 院雲. Active in the 13th century. Awarded the rank of Hokkyo 法橋 (Hokkyō, Hokkyou), the third highest for artists of Buddhist sculpture. See Inpan above for note on extant artwork. In’un 院雲. Active in the 13th century. Awarded the rank of Hokkyo 法橋 (Hokkyō, Hokkyou), the third highest for artists of Buddhist sculpture. See Inpan above for note on extant artwork.

- Inken 院賢. Awarded the highest rank of the Buddhist priesthood (Hōin 法印) although he was not a monk. Bugaku masks (Bugakumen 舞楽面) carved by Inken are reportedly extant, but I have been unable to acsertain their location.

- Inchi 院智. Active in the 13th century. One extant statue attributed to Inchi is an effigy of Prince Shotoku Taishi 聖徳太子 at Ninna-ji Temple 仁和寺 in Kyoto, made around +1252. The same statue is sometimes considered to represent Prince Siddhartha (Shitta Taishi; source Mori Hisashi, Heibonsha). Inchi was awarded the rank of Hogen (Hōgen or Hougen 法眼) in his lifetime, the second highest rank bestowed on artists.

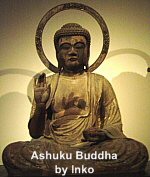

Inko 院康 (Inkō, Inkou). Active in the 14th century. A life-size wooden statue of Ashuku Buddha 阿閃如来 at Kakuonji Temple 覚園寺 in Kamakura was reportedly carved in +1322 by a local sculptor named Inko (birth and death unknown), a member of the Inpa School. Inko 院康 (Inkō, Inkou). Active in the 14th century. A life-size wooden statue of Ashuku Buddha 阿閃如来 at Kakuonji Temple 覚園寺 in Kamakura was reportedly carved in +1322 by a local sculptor named Inko (birth and death unknown), a member of the Inpa School.

- In’no 院嚢 (unsure of spelling ??). Active in the 14th century. The presumed creator of a statue of Priest Myogan Sho-in (Myōgan Shō-in) 明岩正因 enshrined at the Shodenan (Shōdenan) 正伝庵 of Engakuji Temple 円覚寺 in Kamakura.

- Inyo 院誉.

Active in the 14th century. He reportedly carved a small wooden statue (43 cm in height) of the 11-headed Kannon Bosatsu in +1332, in the half-leg pose (木造十一面観音半跏像). See photo at right. The statue was originally located near Tsurugaoka Hachimangu (鶴岡八幡宮) in Kamakura’s Jyuniso 十二坊 (Jyūnisō) district, but it was later moved to its current location at Keisanji Temple 慶珊寺 near Yokohama. According to temple records, the head and headdress were somehow destroyed and a substitute one is now used in its place. (Editor’s Note: The current head appears to be that of a Nyoirin Kannon model). Active in the 14th century. He reportedly carved a small wooden statue (43 cm in height) of the 11-headed Kannon Bosatsu in +1332, in the half-leg pose (木造十一面観音半跏像). See photo at right. The statue was originally located near Tsurugaoka Hachimangu (鶴岡八幡宮) in Kamakura’s Jyuniso 十二坊 (Jyūnisō) district, but it was later moved to its current location at Keisanji Temple 慶珊寺 near Yokohama. According to temple records, the head and headdress were somehow destroyed and a substitute one is now used in its place. (Editor’s Note: The current head appears to be that of a Nyoirin Kannon model).

- From +1251 to 1266, Inpa artists worked side by side with their counterparts in the Enpa and Keiha schools to complete construction of the Rengeoin (Rengeōin) Temple 蓮華王院, more commonly known as Sanjusangendo 三十三間堂 (Sanjūsangendō) in Kyoto. The 1,000 Kannon statues and other pieces made during this collaberative project are still extant and well preserved. Highly recommended for a visit by lovers of Buddhist statuary.

- Despite losing dominance to the Keiha School 慶派 during the Kamakura period, Inpa artists remained active (but on a smaller scale) both in Kyoto and in the outlying provinces. The Inpa school experienced a brief comeback in the late 14th century, commissioned by various Shogun (Shōgun) families and Zen 禅 and Ritsu 律 sect temples north of Kamakura, but their style by that time already incorporated most of the popular nuances of the Kei school. <source JAANUS>

OTHER BUSSHI OF THE HEIAN PERIOD

Kojo 康成.(Kōjō) Known to have repaired a Buddhist statue belonging to Lord Ninjuu in the year +1000. His name appears in the Miraculous Tales of Jizo Bosatsu 地蔵菩薩霊験記, a collection of setsuwa 説話 (tales) compiled from the mid-Heian period into the early Kamakura era. He appears in Volume 1, Story 7, How Ninkō Delivered the First Jizō 地蔵 Sermon. Little else is known of him or his lineage.

MAGAIBUTSU 磨崖仏 (まがいぶつ)

Images Carved in Cliffs, Large Rock Outcrops, or in Caves

KUNISAKI PENINSULA ON KYUSHU ISLAND

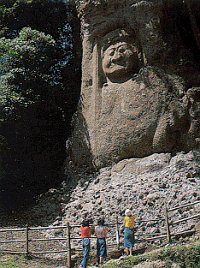

From the Heian Period (794-1185 AD) through the Kamakura Period (1185 to 1333 AD), the Kunisaki Peninsula in Kyushu thrived as a great hub of Buddhist culture in Japan. Countless stone statues, many carved into cliffs, still survive into the present day. This area is reported to contain more than 60% of Japan’s magaibutsu (Buddhist images carved on large rock outcrops, cliffs, or in caves) and sekibutsu (free-standing, movable statues carved from stone). Kyushu is credited as the source of Japanese civilization, from which the seeds of culture were planted throughout the islands. Archaeological findings suggest that Kyushu was the earliest inhabited area of Japan, and historical records show that first contact with mainland Asia originated in Kyushu.

KUMANO MAGAIBUTSU KUMANO MAGAIBUTSU

熊野磨崖仏 - くまのまがいぶつ

Two deities, Fudo Myo-o and Dainichi Nyorai, are carved on a cliff behind Taizo Temple in Tashibu, Oita Prefecture. For more on Kumano and the early spread of Buddhism in this area, see the Pilgrimage Guide. The Dainichi image is six meters high and the Fudo image eight meters. Thought to be Japan’s largest and oldest cliff carvings, they first appear in official court records in 1228 AD, but the actual date of their construction is clouded in uncertainty. Many believe construction occurred sometime in the Heian Era. The many steps leading up to the carvings, according to legend, were built by demons. Engraved on the head of the Dainichi image is a three-phased mandala, reportedly the only surviving example in Japan, and one said to be intimately related to the Shugendo sect of Esoteric Buddhism. <Above photo courtesy of www.oita.isp.ntt-west.co.jp; text adapted from city.bungotakada.com> For much more on cliff carvings, see the Big Buddha page.

RESOURCES

- JAANUS. Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System. Online database devoted to Japanese art history. Compiled by the late Dr. Mary Neighbour Parent, it covers both Buddhist and Shintō deities in great detail and contains over 8,000 entries.

- Dr. Gabi Greve. See her page on Japanese Busshi. Gabi-san did most of the research and writing for the Edo Period through the Modern era. She is a regular site contributor, and maintains numerous informative web sites on topics from Haiku to Daruma. Many thanks Gabi-san !!!!

- Heibonsha, Sculpture of the Kamakura Period. By Hisashi Mori, from the Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art. Published jointly by Heibonsha (Tokyo) & John Weatherhill Inc. A book close to my heart, this publication devotes much time to the artists who created the sculptural treasures of the Kamakura era, including Unkei, Tankei, Kokei, Kaikei, and many more. Highly recommended. 1st Edition 1974. ISBN 0-8348-1017-4. Buy at Amazon

. .

- Classic Buddhist Sculpture: The Tempyo Period. By author Jiro Sugiyama, translated by Samuel Crowell Morse. Published in 1982 by Kodansha International. 230 pages and 170 photos. English text devoted to Japan’s Asuka through Early Heian periods and the development of Buddhist sculpture during that time. ISBN-10: 0870115294. Buy at Amazon.

- The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture, AD 600-1300. By Nishikawa Kyotaro and Emily J Sano, Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth) and Japan House Gallery, 1982. 50+ photos and a wonderfully written overview of each period. Includes handy section on techniques used to make the statues. The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture (AD 300 - 1300)

. .

- Comprehensive Dictionary of Japan's National Treasures. 国宝大事典 (西川 杏太郎). Published by Kodansha Ltd. 1985. 404 pages, hardcover, over 300 photos, mostly color, many full-page spreads. Japanese Language Only. ISBN 4-06-187822-0.

- Bosatsu on Clouds, Byōdō-in Temple. Catalog, May 2000. Published by Byōdō-in Temple. Produced by Askaen Inc. and Nissha Printing Co. Ltd. 56 pages, Japanese language (with small English essay). Over 50 photos, both color, B&W. Some photos at this site were scanned from this book. Of particular use when studying the life and work of Jōchō Busshi.

- Visions of the Pure Land: Treasures of Byōdō-in Temple. Catalog, 2000. Published by Asahi Shimbun. Artwork from Byōdō-in Temple. 228 pages, Japanese language with English index of works. Over 100 photos, color and B&W. Some photos at this site were scanned from this book. No longer in print. Of particular use when studying the life and work of Jōchō Busshi.

- Numerous Japanese-language temple and museum catalogs, magazines, books, and web sites. See Japanese Bibliography for extended list. Also relied on Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺 (Horyuji) catalogs and Asuka Historical Museum.

JAPANESE WEB SITES JAPANESE WEB SITES

|

|