|

|

|

|

PAGE TWO OF FOUR PAGE TWO OF FOUR

1 |  | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4

MONKEY IN JAPAN

PAGE TWO - INDIA & CHINA LORE

Calculating and intelligent, yet

mischievous, vain, and restless.

Akin to the human spirit and passions.

Common motif in Buddhist art & literature.

ORIGINS

India: Hindu Lore (Pre-Buddhist) & Buddhism

China: Zodiac Lore (Pre-Buddhist) & Buddhism

Japan: Buddhist and Shintō Lore

|

SUMMARY PAGE TWO

INDIA AND CHINA - MONKEY LORE. Monkey mythology is an important part of both Hindu/Buddhist lore (India) and Zodiac/Taoist/Buddhist lore (China). In the various tales presented below, the monkey is portrayed initially as foolish, vain, and mischievous. Yet, in each tradition, the monkey learns valuable lessons along the way, makes changes, and eventually gains redemption. The monkey thus embodies the themes of repentance, responsibility, devotion, and the promise of salvation to all who sincerely seek it. This symbolism is still common in Buddhism as practiced today. In modern meditation practices in many Buddhist sects, one must first subdue the “monkey mind” before meditation can yield results. The goal is to overcome the restless monkey mindset, to stop jumping from branch to branch, to stop grabbing whatever fruit comes into sight, to stop being fooled by mere appearances. Salvation is within the grasp of all who seek it if they remain true, sincere, and dedicated.

|

|

|

Hanuman

India, Modern Drawing

Courtesy Khandro-net

Hanuman

Bangkok, Thailand

Royal Palace

Photo courtesy

Masanobu Matsuta

|

|

INDIA - HINDU MONKEY LORE INDIA - HINDU MONKEY LORE

PRE-BUDDHIST MYTHOLOGY

The Sanskrit term Vanara means monkey or forest dweller. Other Sanskrit terms for monkey include Makata and Kapi. In India, the most widely known Vanara is Hanuman, the monkey warrior who appears in the epic Hindu tale Ramayana (5th to 4th century BCE). Even today, Hanuman is a very popular village god in southern, central and northern India, and artwork of Hanuman can still be found easily in India and other nations in Southeast Asia.

Hanuman is a manifestation (avatar) of the Hindu god Śiva. In one version of the story, Śiva and Parvati (“daughter of the mountain”) transform themselves into monkeys and are playing amorous games in the forest when Hanuman is conceived. Since their union took place while in monkey form, Śiva realizes his child will be simian, and instructs Vayu (the wind god) to deposit the gestating seed into the womb of a female monkey named Anjana. Anjana was originally a celestial maiden (apsara) named Punjisthala, but a curse had transformed her into a monkey. Vayu possesses Anjana, with her consent, and she gives birth to Hanuman. Hanuman is thus also called Maruti (son of the wind) and Anjaneya (son of Anjana).

Legend asserts that Hanuman, soon after birth, confused the sun for a fruit that he could eat. When he took flight to catch the sun, he was struck down by a thunderbolt for his foolishness by the Hindu God Indra. The bolt struck Hanuman in the jaw, cutting his cheeks, and henceforth he was called Hanuman (Sanskrit "hanu" means cheek). He lay unconscious until Indra withdrew the bolt’s magic to pacify the wind god Vayu, who had sucked away all the air of the cosmos to show his displeasure with Indra. To make amends and placate Vayu, the gods endowed Hanuman with special godlike powers. As Hanuman grows up, he becomes even more invincible, but he is a trickster and is eventually cursed by the sages for his mischievousness -- he is made to forget his powers until reminded of them by others. In the Ramayana epic, Hanuman’s fellow vanaras help him recollect his powers, which he uses to aid Rama in rescuing Rama’s wife, Sita, from the evil Ravana (the king of the Raksa). Hanuman redeems himself, and becomes a metaphor for bravery, loyalty, and dedication to righteousness. Some scholars believe Hanuman mythology might be the origin of the magical monkey Sun Wu Kong, who appears in the famous Chinese novel Journey to the West. For more on Hanuman and Vanara, please visit the below outside links:

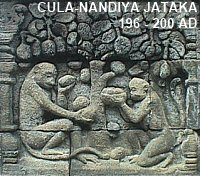

INDIA -- BUDDHIST MONKEY LORE INDIA -- BUDDHIST MONKEY LORE

FROM THE JATAKA OR

TALES OF BUDDHA’S PAST LIVES

Monkey lore plays a prominent role in the early years of Buddhism in India. Among hundreds of tales in the Jataka -- perhaps the oldest extant collection of Buddhist folklore originating in India and Sri Lanka around the 3rd century BC -- the Historical Buddha was said to have lived many prior lives in many different forms before attaining enlightenment.

In the Jataka tales, he appears often in the form of a monkey (e.g., Nandiya), as other animals, as a human, and even as a god. But throughout, he practices generosity, courage, justice, and patience until finally achieving Buddhahood. The Pali Jatakas record 123 past lives as an animal, 357 as a human, and 66 as a god. Devadatta, a cousin of the Historical Buddha, also appears in the various Jataka stories in multiple incarnations, typically as the villain.

|

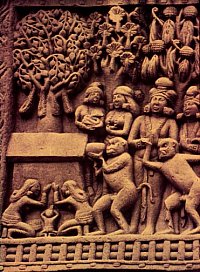

Monkey Offering Honey

to Shakyamuni (Shaka).

North Gate of Great Stupa

at Sanchi, India 50 BCE

Monkeys offering honey to the Buddha (not shown, his presence implied by the platform beneath a bodhi-tree). Such carvings predate any extant written texts. Carved in the sandstone railings, crossbeams, and in gateways of reliquary stupas at places like Bharhut and Sanchi, these early Buddhist carvings from India consistently avoid depiction of the Buddha in human form. In other artwork, the monkey is shown dancing in joy when the meditating Buddha accepts the monkey’s offering of a bowl of honey.

Photo/text courtesy of:

Michael D. Rabe, PhD

Saint Xavier University

|

Depiction of

Mahakapi Jataka

India, Stone Relief

150 BC

In one of his past lives, before attaining Buddhahood, the Historial Buddha was a wise monkey king who enabled his followers to escape from hunters. Here we see a depiction of the "Mahakapi Jataka," in which the future Buddha is a compassionate leader of a troop of monkeys who escape across a river on his back; carved on a stupa railing pillar at Bharhut, c. 150 BC; India Museum, Calcutta. Read this story by clicking here (outside link). Another excellent version of this story is found here (outside link). In this story, the monkey embodies the virtue of generosity.

Photo/text courtesy of:

Michael D. Rabe, PhD

Saint Xavier University

|

|

Four Harmonious Brothers

|

Photo courtesy of

Buddhist Symbols

by Dagyab Rinpoche

ISBN: 0-86171-047-9

|

|

The story of Kapinjala is a popular Jataka tale. The story tells of four animals living in the forest -- a hare, a monkey, a type of bird called Kapinjala, and an elephant. They choose the Kapinjala as their chief and live in harmony and mutual respect. The Kapinjala represents Shakyamuni (Historical Buddha), the hare Sariputra, the monkey personifies Buddha’s disciple Maudgalyayana (outside link), and the elephant Ananda. Read the story here.

(Note: Above animal/human associations come from Rani, PL. 25, Avadana n. 86; Tucci, vol II, 520, Avadana n. 86, vol. III, PL. 124). For more on Maudgalyayana, please see these outside links:

Link One | Link Two

|

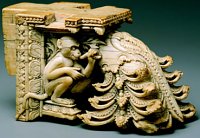

Ivory bracket with monkey

India, Nayak period

First half of 17th century

Size: 8.9 cm x 5.1 cm

Courtesy of the Cynthia

Hazen Polsky Collection

Asianart.com

|

|

Nine Evil Monkeys Nine Evil Monkeys

Dream of King Kriki 訖哩枳王 (Jp: Kiriki-ou)

Adapted from Soka Gakkai

A king who was a devout follower of Kashyapa Buddha (the sixth of seven Buddhas of the past, the last being the Historical Buddha). In the sutra named “Protection of the Sovereign of the Nation” (守護國界主陀羅尼經, Shugo Kokkaishu Darani Kyou), King Kriki has troubling dreams and asks Kashyapa Buddha for an interpretation. One of the king’s dreams involved ten monkeys, who lived together in a group. Nine of them harassed people in the city by stealing their food and drink. The tenth refused to join them and contented himself with what little he had. For this, the other nine monkeys ostracized him. Kashyapa Buddha says the dream represents the conditions of the Buddhist world that will prevail following the death of the Historical Buddha. The ten monkeys represent ten kinds of monks; the ostracized one who has little desire and knows satisfaction represents the true follower, the seeker of the Dharma (Buddhist Law). The other nine monks, represented by the nine greedy monkeys, will slander the true monk when addressing the ruler and ministers of state. They will accuse the true monk of performing evil acts and violating the precepts. As a result, the ruler will banish that monk, and the teachings of the Historical Buddha will then be lost. These monks have nine different ulterior motives, such as the desire for fame and profit. Saicho, the founder of Tendai Buddhism in Japan (see page three) makes reference to the nine bad monkeys chasing away the one good monkey in his Kenkairon Engi (early 9th century AD). The monkey, moreover, is closely associated with the Tendai Shinto-Buddhist multiplex that Saicho established on Mt. Hiei.

CHINA - ZODIAC MONKEY LORE CHINA - ZODIAC MONKEY LORE

PRE-BUDDHIST MYTHOLOGY

The monkey appears often in pre-Buddhist and post-Buddhist China. In Western nations, the monkey is perhaps known most widely as the 9th animal among 12 in the Chinese Zodiac. Most scholars believe the Chinese zodiac originated sometime before 1100 BC, centuries prior to the Historical Buddha’s birth in India around 500 BC.

When Buddhism was introduced to Japan in the 6th century AD, the Japanese eagerly imported both the Buddhist teachings and the zodiac calendar, the latter known as Kanshi or Eto (干支 | えと) in Japanese. In Japan, the Zodiac’s 60-year cycle (sexagenary cycle) was adopted in 604 AD by Empress Suiko, and is known as Jikkan Junishi 十干十二支 (literally “10 stems and 12 branches”). The current cycle started in 1984 AD. For full details, please see the Zodiac page.

|

Koushin Statue

1808 AD

Shoumen Kongou

standing atop

three monkeys

See Page Three

|

|

ZODIAC MONKEY

KOUSHIN 庚申 DAYS/YEARS

On Page Three of this report, we focus on monkey days of great misfortune known in Japan as Koushin days 庚申 (Ch: keng-shen or geng-shen). They occur six times yearly, and once every 60 years (the 57th year of the cycle). Special rites -- influenced greatly by Chinese Taoist and Zodiac beliefs from the post-Buddhist period -- are performed on these days and on the 57th year (the Koushin Year) to ward off evil influences. One of the main players is the monkey, for the term Koushin 庚申 is comprised of two characters -- KOU 庚, the Zodiac stem associated with metal and the planet Venus, and SHIN 申, the ninth branch symbol of the Chinese zodiac and the character for “monkey.” In Taoist traditions based on the Zodiac calendar, on the eve of a Koushin Day, three worms (三蟲) believed to dwell in the human body escape from the body and visit the Court of Heaven to report on the sleeping person's sins. Depending on this report, the court might shorten that individual's life. To prevent this, people stayed awake all night on Koushin eve, and this practice eventually became known as the Koushin Machi (Koushin Vigil, Koushin Wake, 庚申會). Such beliefs were recorded by the late Heian era, but became particularly widespread during Japan's Edo period (1600-1868 AD), when people regularly tried to determine auspicious or inauspicious times before beginning activities (such as a new business or marriage). <This paragraph adapted in part from the Japan Now Magazine (Jan. 1996); see full story at the Asian Studies Network Information Center.> A complete bibliography of this site’s monkey resources is presented on Page Four.

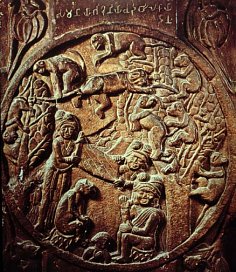

CHINA - BUDDHIST MONKEY LORE CHINA - BUDDHIST MONKEY LORE

Catching the Moon’s Reflection

Journey to the West; The Monkey King

Protector of Horses and Stables

Yuanhou Zhuyue

Famous Buddhist Parable from China

The Chinese story named Yuanhou Zhuyue (Japanese = Enkou Sokugetsu, 猿猴捉月) tells of a group of monkeys who attempt to catch the moon’s reflection, but all are drowned in the effort. This parable, presented below, is hard to date. Buddhism was introduced to China in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, and this parable probably originated during this time or soon thereafter. But I am unsure -- it may have originated earlier, but no later than the 8th century AD.

<Story as quoted by JAANUS>

One night a monkey chieftain saw the bright reflection of the moon in the water below his tree. Thinking that the moon had died and fallen into the water, and fearing that the world would thus slip into darkness, the monkey called together his underlings and commanded them to join tails and together pull the moon out of the water. However, when the monkeys attempted this task, their combined weight was too great, the branch broke, and they fell into the water and drowned.

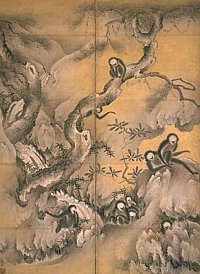

One simple moral of the story is not to recklessly attempt impossible tasks. On a more philosophical level, the image of the monkey attempting to grasp a reflection of the moon is a metaphor for the unenlightened mind deluded by mere appearances. The theme was often depicted in Japanese ink paintings, usually featuring long-armed spider monkeys. The screen paintings by Shikibu 式部 (16c; Kyoto National Museum) and Hasegawa Touhaku 長谷川等伯 (1539-1610; screen painting at Konchiin 金地院, Kyoto), are representative. <end JAANUS quote>

Another interpretation of the parable’s meaning is: “When the unwise have an unwise leader, they are all led to ruin.”

Related Terms

井中撈月. Literally “Ladling the Moon Out of a Well” (Jp. Shou Chuu Rou Getsu). This Chinese phrase refers to the same above parable from China. It is a metaphor for unenlightened people who are deluded by mere appearances. Another term is 心猿 (Jp. Shin-en), literally “the mind of a restless monkey.” This also refers to the mind of illusion as portrayed in the above Chinese moon parable. Other terms include 痴猴 (Jp. = Chikou), also written 癡猴 -- both mean “deluded monkey.”

Journey to the West

西遊記, Japanese = Saiyuuki

Journey to the West is a famous Chinese story (called Hsi-Yu Chi in Chinese). Although compiled by Wu Cheng'en in the 16th century, the legend existed long before that. It is based on a real person named Xuan Zang (602-664 AD), a Buddhist monk who journeyed to India in search of Buddhist sutras. Protecting him on his journey, in the book, are three companions: (1) the monkey named Sun Wu Kong; (2) the pig; and (3) Sandy, the Water Demon (Jp. = Sagojou). Sandy is considered, by some, to be the origin of the Japanese water sprite named Kappa.

Journey to the West tells of the monkey’s revolt against Heaven, of its defeat by the Buddha, of its being cast out of heaven, and then, how it redeems itself and gains immortality by helping the monk Xuan Zang on his pilgrimage to India in search of Buddhist scriptures. The first abridged English translation of this story, by Arthur Waley, was published in 1942, and was entitled Monkey: A Folk-Tale of China. Waley translated only 30 of the 100 chapters of the story. For a detailed overview, see this outside site (site also sells statues of the monkey king). Below is a small segment of the story written by Wayne Kreger of the University of Saskatchewan.

After causing much trouble among various earthly and divine powers, the Monkey King was reported to the heavenly court. He was summoned to heaven, where the Jade Emperor (the ruler of heaven) tried to buy his complacency by giving him a post as a guard in the heavenly stables. This infuriated the Monkey King, who returned to earth and proclaimed himself “Great Sage, Equal to Heaven.” Waves of divine armies were sent to subdue the Great Sage, but all failed. He returned to heaven and continued to cause havoc. Buddha himself was alerted to the problem of the monkey, and came to capture the beast. He offered Monkey King a challenge -- if the Monkey King could leap out of Buddha's reach, he would be left alone to rule heaven. Monkey King sneered at this challenge, thinking it a joke, and leaped to the edge of the universe, where he scratched his name and urinated on a row of five pillars. He then returned to Buddha and boasted of his feat. When Buddha held up his hand and revealed Monkey King's name written on his (the Buddha’s) finger, the monkey knew he had been beaten. Monkey King was imprisoned for five hundred years, until he was released by Guan Yin (Kannon Bosatsu) to aid a Buddhist monk named Xuan Zang on his quest to India to obtain religious scriptures. The story of this journey makes up the bulk of the book “Journey to the West.” <end quote from Wayne Kreger>

Another wonderful review of The Journey to the West can be found here by Aaron Shepard, who writes in one passage: “Your Majesty,” said the gibbon carefully, “we have ever been grateful for that time four centuries ago when you hatched from the stone, wandered into our midst, and found us in this hidden cave behind the waterfall. We made you our king as the greatest honor we could bestow. Still, I must tell you that kings are not the highest of beings. Above them are gods, who dwell in Heaven and govern Earth. Then there are Immortals, who have gained great powers and live forever. And finally there are Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, who have conquered illusion and escaped rebirth.”

“Wonderful!” cried the Monkey King. “Maybe I can become all three!” He considered a moment, then said, “I think I’ll start with the Immortals. I’ll search the earth till I’ve found one, then learn to become one myself!” <End quote by Aaron Shepard>

Another site worth visiting is innerjourneytothewest.com by Walther Sell. It explores the inner meaning of Journey to the West. Mostly written in Chinese, but with some English resources. Numerous images.

|

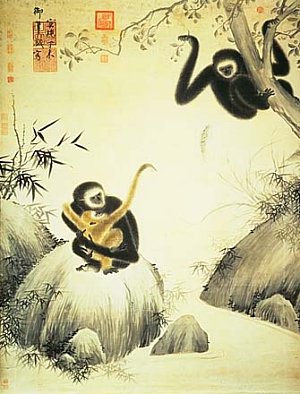

Gibbons at Play

Hsuan-te Emperor (1399-1435 AD), dated 1427 AD

Hanging scroll, ink and color on paper

Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Photo courtesy www.asianart.com/splendors/

One panel from the famous Shikibu Enko

16th Century, Kyoto National Museum

Link shows more photos. Japanese language only.

巖樹遊猿図、式部輝忠、重文

室町時代、16 世紀、京都国立博物館

|

|

Protector of Horses, Protector of the Stables

Quivers Covered in Monkey Hide

|

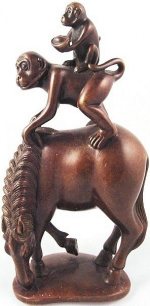

Monkey Riding Horse

Japanese Netsuke

Courtesy rubylane.com

Monkey Riding Horse (ichibanantiques.com)

|

|

In Chinese and Japanese artwork, the monkey is often shown riding the horse. This symbolism too stems from the classic Chinese story (see above) called Journey to the West, in which the Jade Emperor appoints the Monkey to the post of “Protector of Horses” to pacify the monkey’s desire for power and recognition. See parts of this story here (by Aaron Shepard, outside link). The monkey soon discovers that his posting as Stable Protector is empty (without real power or merit), and again returns to his mischievous ways, causing trouble for all until he is defeated by the Buddha. In Chinese and Japanese artwork, the monkey is often shown riding the horse. This symbolism too stems from the classic Chinese story (see above) called Journey to the West, in which the Jade Emperor appoints the Monkey to the post of “Protector of Horses” to pacify the monkey’s desire for power and recognition. See parts of this story here (by Aaron Shepard, outside link). The monkey soon discovers that his posting as Stable Protector is empty (without real power or merit), and again returns to his mischievous ways, causing trouble for all until he is defeated by the Buddha.

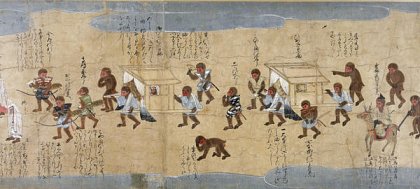

Elsewhere, in the Japanese Saru no Soshi 猿の草子 (Scroll of the Monkey), an entertaining illustrated scroll from the late 16th century (see photo below) describing the marriage of the daughter of the monkey head-priest of Hiyoshi Shrine to a monkey from Yokawa, we find two monkey attendants discussing the proper way to carry a quiver. In those bygone days, Japanese quivers actually had covers made of monkey hide. This monkey-hide covering was believed to protect the warrior’s horse against illness and injuries. <Source: Author Takeuchi Lone, from the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 1996, 23/1-2>

Saru no Soshi (Scroll of the Monkey)

Late 16th Century, One Section of the Japanese Scroll

Photo courtesy of British Museum, where the scroll is kept.

Stable Protector Stable Protector

Toshogu Shrine, Nikko, Japan

A famous carving of the three monkeys is found at the 17th-century Toshogu Shrine, a complex built to honor Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1868 AD). The carving is located on the eaves of the Shinkyusha (Sacred Stable), again reflecting the monkey’s role as protector of the stables, a role that originated in the Chinese novel Journey to the West. Eight panels are carved on the wall of the shrine’s horse stable. The panel shown above depicts the three monkeys "hear no evil, speak no evil, and see no evil."

Sarumimi 猿耳 -- Literally “Monkey Ears”

The origin of the term Sarumimi is unclear, but it may be related to the custom, already established in the Kamakura era, of keeping pet monkeys in the vicinity of stables, apparently to protect the horses from sickness and ill-fortune. <quoted from JAANUS>

12 Zodiac Animals Associated with Eight Buddhist Deities

Exact dates are hard to determine, but it was probably in Japan’s Edo Period (1603 - 1867 AD) that the Japanese began associating each of the 12 Chinese zodiac animals with one specific Buddhist patron deity, the Eight Buddhist Protector Deities. For reasons unknown to me, there are only eight patron Buddhist deities, not 12.

|

EIGHT BUDDHIST PATRONS OF THE 12 ZODIAC ANIMALS

|

|

Zodiac

Animal

|

Buddhist

Patron

|

Year

of Birth

|

|

Rat

|

Senju Kannon

|

1924, 1936, 1948, 1960, 1972, 1984, 1996, 2008

|

|

Ox

|

Kokuzo

|

1925, 1937, 1949, 1961, 1973, 1985, 1997, 2009

|

|

Tiger

|

Kokuzo

|

1926, 1938, 1950, 1962, 1974, 1986, 1998, 2010

|

|

Rabbit

|

Monju

|

1927, 1939, 1951, 1963, 1975, 1987, 1999, 2011

|

|

Dragon

|

Fugen

|

1928, 1940, 1952, 1964, 1976, 1988, 2000, 2012

|

|

Snake

|

Fugen

|

1929, 1941, 1953, 1965, 1977, 1989, 2001, 2013

|

|

Horse

|

Seishi

|

1930, 1942, 1954, 1966, 1978, 1990, 2002, 2014

|

|

Sheep

|

Dainichi

|

1931, 1943, 1955, 1967, 1979, 1991, 2003, 2015

|

|

Monkey

|

Dainichi

|

1932, 1944, 1956, 1968, 1980, 1992, 2004, 2016

|

|

Rooster

|

Fudo Myo-o

|

1933, 1945, 1957, 1969, 1981, 1993, 2005, 2017

|

|

Dog

|

Amida

|

1934, 1946, 1958, 1970, 1982, 1994, 2006, 2018

|

|

Boar

|

Amida

|

1935, 1947, 1959, 1971, 1983, 1995, 2007, 2019

|

|

LEARN MORE: Click here for details on the Eight Buddhist Patrons, or click here for details on Chinese Zodiac cosmology. Also visit the 12 Generals of Yakushi Nyorai for another grouping of Buddhist deities with the 12 Zodiac animals. Yakushi Nyorai is the Healing Buddha (the Medicine Buddha), and in the centuries following the introduction of Buddhism to Japan, Yakushi’s 12 generals became associated with the 12 animals of the Zodiac. In Japanese art, the 12 generals often appear with the 12 animals in their head pieces. There are variations in this latter grouping. Among some, the general Makora (also called Makura; Skt. = Mahoraga) is associated with the monkey. But at Kakuonji Temple in Kamakura, the general Anchira (Skt. = Andira) is associated with the monkey.

|

|

SUMMARY PAGE TWO

INDIA & CHINA - MONKEY LORE

Monkey mythology is an important part of both Hindu/Buddhist lore (India) and Zodiac/Buddhist lore (China). In the various tales presented above, the monkey was originally portrayed as foolish (India and China), vain (China), and mischievous (both). Yet, in each tradition, the monkey learns valuable lessons along the way, makes changes, and eventually gains redemption. The monkey thus embodies the themes of responsibility and devotion, and more importantly, the promise of salvation to all who sincerely seek it. This symbolism is still common in Buddhism as practiced today. In modern meditation practices in many Buddhist sects, one must first subdue the “monkey mind” before meditation can yield results. The goal is to overcome the restless monkey mindset, to stop jumping from branch to branch, to stop grabbing whatever fruit comes into sight, to stop being fooled by mere appearances. Salvation is within the grasp of all who seek it if they remain true, sincere, and dedicated.

JUMP TO PAGE THREE JUMP TO PAGE THREE

|

|