|

|

|

|

PAGE FOUR OF FOUR PAGE FOUR OF FOUR

1 | 2 | 3 |

MONKEY IN JAPAN

PAGE FOUR - BIBLIOGRAPHY

Calculating and intelligent, yet

mischievous, vain, and restless.

Akin to the human spirit and passions.

Common motif in Buddhist art & literature.

ORIGINS

India: Hindu Lore (Pre-Buddhist) & Buddhism

China: Zodiac Lore (Pre-Buddhist) & Buddhism

Japan: Buddhist and Shintō Lore

DEDICATION

These monkey pages are dedicated to Dirk Ross (a scholar of meteorites), who sparked my research on the Kōshin (Koushin, Koshin) ritual involving monkeys. Dirk runs a blog on recent landings of fireballs-meteorites.

MAIN RESOURCES

|

KŌSHIN PHOTO LINKS KŌSHIN PHOTO LINKS

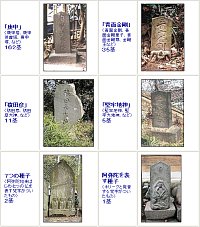

The below web sites catalog and map hundreds of Kōshin (Koshin) statues throughout Japan. The oldest surviving stone stele dedicated to Kōshin is dated 1375 AD. Found in Yamagata prefecture, it was erected by a local noble named Ito Shigemasa. Another 14th century tablet has been identified in Nagano, and it mentions the name Shōmen Kongō. The oldest statue from the Kamakura area is dated 1665 AD. One of the best web resources is KCN-NET, a Japanese-language site created by Mr. Tatsuro Gotoh:

www.kcn-net.org (lots of photos)

www.kcn-net.org/list (locations)

www.kcn-net.org/home (home)

Other Kōshin Sites

J = Japanese, E = English

Calendar of Koushin Days (J)

www.koshindo.com (J; photo of three worms)

ancientway.com (English Essay; 3 Worms & Taoism)

ja.wikipedia.org/wiki1/ (10 stems; J)

ja.wikipedia.org/wiki2/ (Koushin summary; J)

ja.wikipedia.org/wiki3/ (Koushin Statues; J)

ja.wikipedia.org/wiki4/ (Makura; J)

- Keng-Shen (Kōshin) and Sex

Below quoted from writings of Daniel A. Foss

University at Buffalo, The State University of New York

Mr. Foss is quoting from Su Nu ("Immaculate Girl"), the sex goddess and initiatrix of the Yellow Emperor into How It Is Done:

- One must not unite yin and yang on the sexagenary cycle days “ping-tzu” and ”ting-ch'ou” following the summer solstice and ”keng-shen” and ”hsin-yu” following the winter solstice, as well as when one has just washed the hair or completed a long trip, when tired, overjoyed, or enraged. Men in their declining years should not foolishly shed their ”ching.”

- Kōshin Vigil. Japan Now Magazine (Jan. 1996); see full story at the Asian Studies Network Information Center.

- Kōshin Hall. The largest, oldest, and most popular Kōshin hall in Japan is part of the Shitennōji Temple in Osaka. Dates for the Kōshin vigil (held six times each year) and the annual Kōshin festival are found here (Japanese language only).

|

THREE MONKEYS RESOURCES THREE MONKEYS RESOURCES

Three Monkeys = San-en 三猿

See No Evil, Speak No Evil, Hear No Evil

Mizaru, Iwazaru, Kikazaru = 見ざる、言わざる、聞かざる

This web site (onmarkproductions.com) assumes that the three no-evil monkeys were an innovation created by the Japanese. The closest association is with Mt. Hiei, the home of Japan’s Tendai Sect and the Tendai Shintō-Buddhist multi-complex (see Page Three). However, the origin of the three is still unclear, for the monkey’s presence in early Japanese Kōshin rituals is not explained, except for the monkey’s implicit ideogram connection (the monkey kanji appears in the characters for the Kōshin day). Furthermore, I have been unable to find three-monkey artwork from China or India that predates Japanese examples. Nevertheless, this proves nothing, and it may yet be discovered that the three-monkey motif originated in earlier Chinese Taoist/Buddhist practices, or perhaps in even older Hindu traditions. The oldest surviving stone stele in Japan dedicated to Kōshin is dated 1375 AD (source Professor Livia Kohn, Boston University). Found in Yamagata prefecture, it was erected by a local noble named Ito Shigemasa. Another 14th century tablet has been identified in Nagano, and it mentions the name Shōmen Kongō. The oldest statue in the Kamakura area is dated 1665 AD.

- Emil Schuttenhelm at Three-Monkeys.Info. Schuttenhelm has collected artwork of the "three monkeys" for many decades and is always trying to find out more. His web site is incredibly informative. Schuttenhelm’s web pages can be viewed in English, German, French, Dutch, or Japanese. He also, along with Bruce Kittess (see below link) maintains a site called thethreemonkeys.com that provides information on the gatherings and events of numerous collectors of three-monkey artwork.

- Bruce Kittess at The Three Monkeys. Writes Bruce: “Around 500 BC, the Analects of Confucius (Chn. = Lùnyǔ 論語; Jp. Rongo) was written by the disciples of Confucius (551-479 BC). In Lùnyǔ XII, 1 it is said: ‘Look not at what is contrary to Li, listen not to what is contrary to Li, speak not what is contrary to Li.‘ Li means regulation of conduct, custom and law, and chi means book. Confucius advises: Confucius, who edited the Book of Poems (dating from 1,000 BC to 600 BC) from 3,000 poems to 300 verses, said that the 300 verses could be summed up in a single phrase: ‘Don't think in an evil way.’ (II.2) In the early 9th century AD, the Japanese monk Saicho founded the Tendai Buddhist sect in Japan. This sect held monkeys to be the sacred messengers of Buddha and as mediators to reward or punish humans depending on their conduct. <end quote>

Editor’s note. The Lùnyǔ (XII, 1) actually gives four warnings:

非禮勿視, 非禮勿聽,非禮勿言, 非禮勿動

1. Look not at what is contrary to propriety; 非禮勿視 (see no evil)

2. Listen not to what is contrary to propriety; 非禮勿聽 (hear no evil)

3. Speak not what is contrary to propriety; 非禮勿言 (speak no evil)

4. Make no movement which is contrary to propriety; 非禮勿動 (do no evil)

Since it is difficult to portray number four pictorially, it was no doubt dropped in Japanese artwork. To read the above passage from the Lùnyǔ, visit Chinese Classics & Translations.

- Mr. Vin Callcut at Oldcopper.org

- THE NUMBER THREE & THREE MONKEYS. There is no agreement on the origin of the three-monkey motif. Is it from India, China, Korea, or Japan? This site assumes that the three-monkey motif is an innovation attributed to Japan‘s Tendai sect. The motif may have developed from the Three-Kami-Three-Buddha-Formula of Japanese Tendai Buddhism at Mt. Hiei, or possibly from the core Tendai principle of triple truth 三学, i.e., (1) all things are void and without essential reality; (2) all things have a temporal or provisional reality; (3) all things are both absolutely unreal and provisionally real at the same time. Alternatively, the three monkeys might represent the Three Truths of Buddhism, which are: (1) life is suffering; (2) suffering is caused by our desires, and; (3) eliminate desire and thereby eliminate suffering. Or perhaps it stems from the three-star constellation named Sandaisei 三台星 after which the Tendai sect itself is named. But most probably (in my mind), the three monkeys are a Japanese innovation associated with the three worms of the Taoist Kōshin ritual. The number three is very important to Buddhists in India, China, Japan, and other nations in mainland Asia (details here). There are literally dozens of other important concepts related to the number three, making it extremely hard to pinpoint the origin of the three-monkey motif. If your computer can display Japanese kanji, visit this outside site, then scroll down until you come to the section for “three.” Lots of intriguing possibilities.

At the risk of sounding the fool, I would like to submit my own interpretation. First, the Kōshin ritual is most strongly linked with Shōmen Kongō, the blue-colored Yasha of Hindu lore, who is associated with the powers of healing, who represents the “east,” and who is considered the king of the Yasha. Now, let us recall that Saichō himself, the founder of Tendai Buddhism in Japan, carved various statues of the Yakushi Nyorai (the Buddha of Healing and Medicine) during his lifetime. Yakushi Nyorai is associated with the color “blue” and represents the “east.” Yakushi Nyorai, furthermore, is protected by 12 Yasha Generals, who represent the 12 vows of Yakushi Nyorai. These 12 Generals are constantly waging war on illness and disease. They originate in Hindu lore, but later become protectors of the Buddhist Law. These 12 Yasha Generals wear effigies of the 12 Zodiac animals in their headdresses.

3 + 9 = 12 3 + 9 = 12

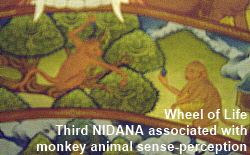

Might not the association between KŌSHIN and SHŌMEN KONGŌ originate here? The number three (three monkeys) plus the number nine (the nine monkeys in King Kriki’s dream mentioned in Saichō’s writings; the nine halls Saichō ordered constructed at Enryakuji Temple) equals twelve. The three worms and nine parasites in the Taoist Kōshin ritual also add up to twelve, and 12 Yasha protect Yakushi Nyorai, the Buddha of Medicine and Healing. Moreover, the Historical Buddha spoke of the Twelve Causes of Suffering, and in many Wheel of Life (Thanka) paintings, the doctrine of the 12 Nidana (Skt., 12-linked Chain of Causation) is painted around the wheel. The third nidana is Vinnyana, or awareness. It symbolizes animal sense-perception, and is depicted as a monkey climbing a tree.

There is other overwhelming evidence for the YAKUSHI connection. There are a total of 21 shrines at Mt. Hiei, known as the “21 Sannō Group” (Sannō Nijūissha 山王二十一社). These 21 shrines are split into three groups of seven -- the three groupings represent the three main Buddha/Kami of the Tendai complex, who are Shaka, Yakushi, and Amida. They in turn represent the three most important Shintō KAMI (deities) of the Hie shrine complex. These three Kami are Omiya (大宮), Ninomiya (二宮), and Shōshinshi (聖真子). The so-called Upper Seven Sannō Shrines (Sannō Kami no Shichisha 山王上七社) form the core of the Sannō complex. They are associated with Shaka, are known as The Big Hiei group, and are associated with the seven stars of the Big Dipper. The next group of seven shrines, known as The Little Hiei group, is associated with Yakushi Nyorai. Furthermore, Yakushi traditionally assumes seven different forms as a healer. These forms are known as the “Seven Emanation Bodies of Yakushi,” which are described in various Sanskrit and Chinese texts. A list of all seven manifestations can be found here.

Thus, in my mind, the association of the three monkeys with the Kōshin ritual (three worms, nine parasites, equals 12); the invocations to the healer Shōmen Kongō (blue, east, king of the Yasha); the importance of the number three (and seven) in Tendai tradition; Saichō’s long-standing patronage of Yakushi (blue, east, Medicine Buddha, protected by 12 Yasha, lord of the “Little Hiei” group of seven shrines) -- all this fits tightly together into a systematic pattern of faith and devotion directed toward Yakushi Nyorai, the Buddha of Medicine and Healing.

I may be wrong, but in my research on Tendai beliefs, the above interpretation sounds very “believable” -- and the evidence presented here is hard to dismiss as mere coincidence. Thus, I prefer my own “unproven” interpretation over the “standard” interpretation found at most web sites devoted to monkey lore. These sites, without citing references, claim the three monkeys originated in China or India. I believe this is wrong -- the three monkeys are mostly likely a Japanese innovation.

- CHINA -- TAOISM & MAGIC. Below text quoted from this outside site. The fact that no record of Shinto antedates the introduction of Chinese script makes it difficult to distinguish between Taoist affinities and influences on Japanese Shinto/Buddhist features, such as the cult of holy mountains, the representation of the human soul as a bird, bird dances, the representation of the world of the dead as a paradisiac country of immortality, and the concept of the vital force (tama, in objects as well as in man). Like Taoism, Shinto is the religion of the village community. There was never an attempt to implant a Taoist religion officially in Japan, but a random choice of Taoist beliefs and customs have, at various ages, been adopted and transformed at the Japanese court, in the temples, and among the people. Records from the early 7th century contain traces of Taoism, which was appreciated chiefly for its magical claims. The "masters of Yin and Yang" (ommyo-ji), a caste of diviners learned in the I Ching (of Chinese astrology), and occult sciences who assumed importance at court in the Heian period (8th-12th century), probably were responsible for the introduction of Taoist practices, such as the Keng-shen (Japanese Kōshin) vigil and the observance of directional taboos (katatagae). In the 8th century, disputations were held at the Japanese court over Buddhism and the philosophy of Lao-tzu and Chuang-tzu. The Pao-p'u-tzu was known, and Kobo Daishi, the founder of Shingon Buddhism, reported (in 797 AD) on Taoist physiological practices and beliefs in immortals. Buddhist (Shingon and Tendai) ascetics, wandering healers, and mountain hermits known as yamabushi probably came closest to Taoism in their techniques for prolonging life (abstinence from grains, etc.) and their magical arts (exorcisms, sword dance) and objects (mirrors, charms). Taoist mysticism lives on in that it has influenced the two Chinese Zen schools of Lin-chi (Jp = Rinzai) and Ts'ao-tung (Jp = Soto), both introduced to Japan in the 12th and 13th centuries and both still active in Japan today. <end quote> Click here for a large PDF file providing references to hundreds of English-language Taoist publications.

- TENDAI MEDITATION PRACTICES IN JAPAN. “The Fundamentals of Meditation Practice” by Ting Chen; translated by Dharma Master Lok To; Edited by Sam Landberg and Dr. Frank G. French. 182 pages. View PDF file here. The mind of most humans is never at rest, never empty or still. It "runs" continuously, like a horse. It also "jumps" from one branch to another, like a monkey in the forest. Traditionally, in the meditation practices of Tendai Buddhists, the mind is said to be like a monkey that has been restricted to a small space, where it can no longer jump and skip about. A fixed mind that cannot stray is like a bound monkey. As applied to meditation practice, it means fixing your attention on the tip of your nose, on your navel, or an inch and a half below it. As it is, you soon discover that the mind's activity is like a monkey, never stopping for an instant. The advice that is traditionally given is to limit this monkey's movement. The Chih-in (Chih-Kuan) means stopping and refers to stopping the false or misleading activity of the mind. To do this, to tether the monkey mind by practicing Chih, the first step is to fix the mind on a single object to keep it from wandering from one object to another.

- MOUNTAIN MYTHOLOGY FROM INDIA. Monkey associations between India and Japan ?? Parvati (Parvathi, Parvathy). The Sanskrit word Parvata means mountain, and Parvati is known in Hindu myth as the “daughter of the mountain." In India, she is worshipped as the deity of hills and mounds, and also as a patron deity of childbirth. Married to Shiva and mother of the Hindu monkey warrior Hanuman. Her father is Himavat (who personifies the Himalaya mountains) and her mother is Mena, one of the Apsara. For more details, see www.exoticindiaart.com. This may (or may not) be directly related to the sacred monkey at Mt. Hiei in Japan. But the mythology is very similar. In Japan, the sacred monkey is the messenger of the mountain king Sannō, and the monkey avatar Sannō Gongen symbolizes fertility and is worshipped as a deity of childbirth.

- TIBET - Monkey Lore. The Year of the Monkey is considered especially auspicious, for it was in one of these that Guru Padmasambhava appeared on this earth to teach Vajrayana Buddhism with an emphasis on Mantrayana and Dzogchen (the attitude of Great Perfection). A number of lineages, especially in the Nyingma (old tradition), observe this anniversary by offering important teachings more widely than usual. Also, in many Wheel of Life paintings, the doctrine of the twelve Nidana (12-linked chain of causation) is painted around the wheel. The third nidana is Vinnyana, or awareness. It symbolizes animal sense-perception, and is depicted as a monkey climbing a tree. <above photo from Tibetan Tanka in private collection of Mark Schumacher>

- KOREA -- Kyongsin. www.koreanculture.re.kr/vol3/main/main2/pdf/Peter.%20Yoon.pdf

Kings Wonjong and Ch’ungnyol both held Taoist rituals regularly and in greater frequency than the average for the entire Koryo Period. These two kings account for more than 25 percent (37 of 202) of all rituals in this period. The kings appear to be devoted to the Taoist practices and rituals for the benefit of health and longevity. There the Taoist custom of observing the night of the day kyongsin (Korean name; called Shou-keng-shen in Chinese) was very popular with King Ch’ungnyol and the members of the aristocratic class of the Koryo Era. Also see “Sourcebook of Korean Civilization,” in Peter Lee, ed., pp. 444-45; Kao-li t’u ching, 18:1b6, translated by Hugh Kang and Edward Shultz.

- TAIWAN, Taipei Economic and Cultural Office

Year of the Monkey Accents Zest for Life, Good Humor

www.taipei.org/feature/monkey%20life/monkeylife.html

- SINGAPORE, Tien Tai Monkey God

Birthday of the Monkey God, occurs in February and September/October. This religious holiday celebrates the birthday of T'se Tien Tai Seng Yeh, the Monkey God, who cures the sick and frees the hopeless. It is celebrated twice a year in several Chinese temples in Singapore, especially in the Soon Thian Keng Temple on Bukit Permei. During the ceremony mediums with their cheeks and tongues pierced with skewers go into a trance and write out charms in their blood. Chinese parents ask the Monkey God to godparent their children in hopes that their children will grow up strong like the Monkey God.

MONKEY ADAGES, PHRASES, CONCEPTS

- Monkey Guards Against Demons from Northeast

In Japan, monkey statues are thought to guard against oni (Japanese term for “demons”), since the Japanese word for monkey (猿 saru) is a homonym for the word 去る, which means to “dispel, punch out, push away, beat away." Thus monkeys are thought to dispel evil spirits. For more on monkey-related ideograms, please click here.

Above chart from Professor Kelley L. Ross (see below)

- Says Professor Kelley L. Ross, Valley College, LA. See above chart and his site at: friesian.com/yinyang.htm. The arrangement of the I Ching trigrams (the Chinese Book of Changes) around the compass reflects Chinese geomancy (feng shui), i.e., the determination of the auspicious or inauspicious situation and orientation of places (cities, temples, houses, or graves). Chinese cities are properly laid out as squares, with gates in the middle of the sides facing due north, east, south, and west. The diagonal directions are then regarded as special "spirit" gates: northwest is the Heaven Gate; southwest the Earth Gate; southeast the Man Gate; and northeast the Demon Gate. The northeast was thus the direction from which malevolent supernatural influences might particularly be expected. The situation of the old Japanese capital city of Kyoto is particularly fortunate. To the northeast is a conspicuous, twin-peaked mountain, Mt. Hiei (corresponding to the Mountain trigram), which is crowned with a vast establishment of Buddhist temples to guard the Demon Gate. < end quote>

|

- 猿も木から落ちる (Jpn. = Saru mo Ki kara Ochiru). Meaning = Even monkeys fall from trees. There is a related proverb associated with the Kappa (a water sprite associated with the simian), which goes: “Kappa no Kawa Nagare.” This means “even Kappa can drown; even a Kappa can be swept away by the river.” Since Kappa are excellent swimmers, this proverb means that "even experts can make mistakes."

- 三匹猿 (Jpn. = Sanbiki Saru). Sometimes spelled Sambiki Saru. Three monkeys / three apes (see no evil, speak no evil, hear no evil).

- 猿に木登りを教える (Jpn. = Saru ni ki-nobori o oshieru).

To teach a monkey to climb a tree (i.e., a foolish endeavor).

- 猿に芸をさせる (Jpn. = Saru ni gei o saseru). To make a monkey do tricks.

To have someone blindly do one’s bidding.

- 犬猿の仲 (Jpn. = Ken-en no naka). At loggerheads. In the West they say “like cats and dogs” to mean unfriendly relations. In Japan, they say “like dogs and monkeys.”

- 猿真 or 猿似 (Jpn. = Sarumane). Literally “monkey imitator.” Translated variously as blind imitation, indiscriminate imitation, monkey see monkey do, blind follower. Something done without thought, as a monkey who imitates humans. The Japanese also says “Sarumane wa yameru,” which means “Don’t be a copycat.”

- 猿知恵 (Jpn. = Sarujie or Saruchie). Shallow cleverness, as with a monkey who imitates humans.

- 猿股 (Jpn. = Sarumata). Red underpants (lit. monkey underwear), which equates to the red buttocks of female monkeys in heat, and thus symbolizes fertility.

- 獮猴地 (Jpn. = Sengochi, センゴチ). The place in India called Vaisali where the Historical Buddha preached. Also written 獮猴江.

- 馬上蜂猴 (Chn. = Mǎ Shàng Fēng Hóu). Literally "Horse above bee monkey." Meaning = "May you quickly become a noble person." To bring good fortune, traditional Chinese artwork often depicted a monkey atop (riding) a horse, symbolizing the Chinese good-luck expression “Ma Shang Feng Hou.” This phrase was used often as a closing in letter writing, conveying the idea "may you be immediately awarded noble rank." The monkey (pronounced “Hóu” in Chinese) is a homonym of another Chinese word meaning "nobleman." The term Mǎ Shàng means "immediately," but its literal translation is "on a horse." The pronunciation of the Chinese word for "bee" is a homonym of the word “feng;” thus “Fēng Hóu” can mean either "bees and monkeys" or "be awarded noble rank."

- 心猿意馬 (Chn. = Xīn Yuán Yì Mǎ, or Hsin Yuan Yi Ma). An untrained mind is like a wild monkey or untamed horse. Phrase originated in Buddhist writings & literally means "heart monkey, mind horse" and refers to the restless, unruly consciousness of the common person.

- 意馬心猿 (Chn. = Yì Mǎ Xīn Yuán, or Yi Ma Hsin Yuan). Another version of the preceding entry. An untrained mind is like an untamed horse or wild monkey. Mind like a horse and heart like a monkey. Horses must be broken in. Monkeys are restless and intractable.

- 虎體猿臂 (Chn. = Hǔ Tǐ Yuán Bì). Literally "tiger body, ape arms." Used to describe a physically imposing person of strong and healthy body.

- Mu Hou Erh Kuan (Chinese). Means "macaque monkey, but clothed," a phrase originating in Ming Dynasty theater and used to criticize a person as being human in appearance only, or to describe a person of fretful disposition, like a monkey uncomfortable in human clothing.

- Sha Chi Ching Hou (Chinese). Means "kill chicken, scare monkey;" taken from a Ching Dynasty novel. It means to make an example of one person in order to deter others.

- 六窗一猿 (Chinese). Six windows and one monkey. Climbing in and out, referring to the six organs of sense and the active mind.

- 心猿 (Chinese). Literally “heart of monkey,” meaning the mind as a restless monkey. Also see following Jataka story (outside link).

- Makata (Sanskrit). The monkey, who personifies the mind of illusion. In pre-Buddhist Hindu lore, the monkey king HANUMAN is struck in the jaw by a bolt of lightening from Lord Indra for thinking the sun was a fruit which he (Hanuman) could eat. The term “hanu” literally means “jaw.”

- 愚 (Chinese) Monkey-witted, silly, stupid, ignorant.

- 攀覺 (Chinese). Seizing and perceiving, like a monkey jumping from branch to branch, i.e., attracted by externals, unstable.

- Monkeys and Foxes in Japanese Folktales (courtesy Yoshi-Yoshi)

http://pweb.sophia.ac.jp/~britto/deekid/task17/yoshi17.html

- 12 Generals of Yakushi Nyorai

Among the 12 Generals of Yakushi Nyorai, it is Magoraha who is most often associated with the monkey in Japan. Yakushi Nyorai, along with his 12 Generals, arrived early in Japan (Asuka Period) from Korea and China, and soon appeared in temples throughout the nation. As such, the 12 Generals of Yakushi Nyorai are among the very first Buddhist deities to be introduced to Japan in the 6th and 7th century AD. By the Kamakura period, the twelve generals become associated with the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac, and sculptures thereafter often show an animal in the head dress of each general.

MONKEY CHARMS IN JAPAN MONKEY CHARMS IN JAPAN

Below text courtesy Dr. Greve

Migawari-zaru 身代わり猿 is the name of a lucky monkey charm in Nara-machi, Japan, which reportedly takes on your bad luck. In the old part of Nara City, there is a special custom to hang out a small red monkey charm to ward off evil, and a special Kōshin-do (Kōshin Hall) is dedicated to the blue-faced heavenly guardian called Kōshin-san. Good-luck charms modeled after the monkey, who acts as a messenger for Kōshin-san, are hung from eaves of houses in Nara-machi so that evil spirits can be driven away. The charm is called Migawari-zaru, meaning "substitution monkey," because the monkey charm reportedly deals with disasters and bad luck in place of the people. One doll for each person of the home is hung on the eves of the house.

The Kōshin deity was introduced to Japan from Chinese Taoism, where the deity was also venerated. That Chinese practice became extremely popular among the Japanese townspeople during the Edo period, but had arrived in Japan much earlier, in the Heian Era. The basic story goes like this. According to the old lunar calendar, each year there are six Kōshin days of the monkey. Three worms which inhabit the human body (san-shi no mushi) escape from the body on these days and report the sins of the people to the gods. Kōshin was a popular deity that protected those who should be punished for their sins, but his messenger, the monkey, was punished instead. Hence the name Migawari-zaru -- substitution monkey. Another name for the monkey charm is Negai-zaru, or “monkey for wishes.” If you write your wishes on the back of the monkey charm and hang it up, your wishes are said to come true. <end quote from Dr. Gabi Greve>

LINKS FROM DR. GABI GREVE

Return to Monkey (Page One)

|

|