|

|

|

|

EARLY JAPANESE BUDDHISM

Asuka Era Through Heian Era

Condensed Version (Extended Version Here) Condensed Version (Extended Version Here)

First Published: June 1, 2008

Written for World History Encyclopedia

The impact of Buddhism on Japan’s political, religious, and artistic development is impossible to exaggerate. Today, some 14 centuries after Buddhism reached its shores, Japan remains one of the world’s great centers of Buddhist practice and art, and a major wellspring for the ongoing migration of Buddhist traditions to the West.

|

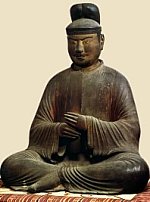

Shōtoku Taishi

Painted Wood

H = 84.3 cm

Nara Era, 8th Century

Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺

Legends about Prince Shōtoku are riddled with folklore. Modern-day scholars claim that Shōtoku legends are largely fabricated, that his role in introducing Buddhism to Japan is exaggerated. They say his legend was created by those who murdered his blood line, both to appease his angry spirit and to spearhead the adoption of Buddhism as a tool of imperial (state) control. Please visit the Shōtoku Taishi page for details.

|

|

Originating in India around 500 BC, Buddhism swept across Asia in just 1000 years. It came last to Japan, crossing the sea from Korea in the mid-6th century. It spread fast under the patronage of regent Shotoku (Shōtoku) Taishi 聖徳太子 (+574-622), the nephew of Empress Suiko 推古 (reigned +592 to 628). Shōtoku embraced the new faith and became one of its first converts. He fostered its acceptance as both a superior religious philosophy and a powerful political tool for creating strong centralized governance under the emperor’s guidance. Shōtoku is credited with constructing seven temples, centralizing state administration, importing Chinese bureaucracy, and enacting a 17 Article Constitution that established Buddhist ethics and Confucian ideals as the moral foundations of the young Japanese nation. During his regency, many missions were dispatched to China (see this outside link for missions to China). Many miraculous tales were created in the centuries after his death -- tales that mostly exaggerate his contribution to Japanese Buddhism (see sidebar at right). Prince Shōtoku never became a monk, but in modern popular belief he is revered as a Buddhist saint. Originating in India around 500 BC, Buddhism swept across Asia in just 1000 years. It came last to Japan, crossing the sea from Korea in the mid-6th century. It spread fast under the patronage of regent Shotoku (Shōtoku) Taishi 聖徳太子 (+574-622), the nephew of Empress Suiko 推古 (reigned +592 to 628). Shōtoku embraced the new faith and became one of its first converts. He fostered its acceptance as both a superior religious philosophy and a powerful political tool for creating strong centralized governance under the emperor’s guidance. Shōtoku is credited with constructing seven temples, centralizing state administration, importing Chinese bureaucracy, and enacting a 17 Article Constitution that established Buddhist ethics and Confucian ideals as the moral foundations of the young Japanese nation. During his regency, many missions were dispatched to China (see this outside link for missions to China). Many miraculous tales were created in the centuries after his death -- tales that mostly exaggerate his contribution to Japanese Buddhism (see sidebar at right). Prince Shōtoku never became a monk, but in modern popular belief he is revered as a Buddhist saint.

The Korean and Chinese missionaries who introduced Buddhism to Japan brought rituals and texts from both the Theravada and Mahayana schools, but the Mahayana form in particular struck a chord with its promise of salvation to both monastic followers and laity alike. The early missionaries also brought their art and techniques for reproducing Buddhist icons and sutras. Three texts were of great influence in Japan -- the Lotus Sutra, the Sutra of Golden Light, and the Benevolent Kings Sutra. These were called the "Three Scriptures Protecting the State." Indeed, the Japanese court's early support for Buddhism was based largely on the court's desire to use Buddhism as an instrument of state power and consolidation rather than an instrument of salvation for the masses. Buddhist ceremonies at the time were organized predominantly for the court to ensure the welfare of the country, to expel demons of disease, and to ensure rain and thus abundant harvests.

Buddhism quickly became the state creed. By the 8th century, Emperor Shomu (d. 756) ordered the establishment of a nationwide system of provincial temples. This fast transition, however, was not always peaceful. In Prince Shotoku’s time, it had sparked a war between the pro-Shinto faction (Mononobe clan) and pro-Buddhist forces (Soga clan). Buddhism won the day, but its subsequent success owed much to its tolerance and absorption of the older deities of the indigenous Shinto mountain cults. Before Buddhism, Shinto shamanism and mountain worship were the predominant forms of native faith. Japan’s pre-Buddhist beliefs in nature spirits and holy men with magical powers were incorporated into Buddhism during the Nara (645 - 794) and Heian (794 - 1185) periods, resulting in a complex blend of Shinto-Buddhist practice.

|

Enno Gyōja

Kamakura Era, 13C

Photo Courtesy:

Cleveland Museum of Art

En no Gyōja

Father of Shugendo

Wood, Kamakura Era ?

Collection of

Janine Moulton

|

One of the most celebrated mountain sages was En no Gyoja (Gyōja) 役行者. This legendary holy man was a mountain ascetic (yamabushi) of the late 7th century. Like much about Shinto-Buddhist syncretism, his legend is riddled with folklore. He was a diviner at Mt. Katsuragi on the border between Nara and Osaka. Said to possess magical powers, he was expelled in 699 to Izu Prefecture for “misleading” the people and ignoring state restrictions on preaching among commoners. He is considered the father of Shugendo (Shugendō), a major syncretic movement that combined pre-Buddhist mountain worship with Buddhist teachings. Popular lore says he climbed and consecrated numerous sacred mountains. One of the most celebrated mountain sages was En no Gyoja (Gyōja) 役行者. This legendary holy man was a mountain ascetic (yamabushi) of the late 7th century. Like much about Shinto-Buddhist syncretism, his legend is riddled with folklore. He was a diviner at Mt. Katsuragi on the border between Nara and Osaka. Said to possess magical powers, he was expelled in 699 to Izu Prefecture for “misleading” the people and ignoring state restrictions on preaching among commoners. He is considered the father of Shugendo (Shugendō), a major syncretic movement that combined pre-Buddhist mountain worship with Buddhist teachings. Popular lore says he climbed and consecrated numerous sacred mountains.

By the 9th century, Buddhist temples were constructed alongside Shinto shrines on many sacred mountains, epitomized by the powerful Tendai temple-shrine multiplex on Mt. Hiei (Shiga Prefecture) and by the holy places throughout the Kumano mountain range. The native Shinto kami (deities) residing on these peaks were considered manifestations of Buddhist divinities, and pilgrimages to these sites were believed to bring double favor from both their Shinto and Buddhist counterparts. Another major center of syncretism was the Kasuga shrine complex in Nara. The number of deities proliferated. Despite earlier resistance, syncretism was relatively smooth and marked by religious tolerance .

Shinto-Buddhist syncretism was actually formalized and pursued based on a theory called Honji Suijaku, with Shinto gods recognized as manifestations (suijaku) of the original Buddhist divinities (honji). In the later Kamakura period some Shinto sects proposed the opposite, proclaiming the Shinto gods as honji and Buddhist deities as suijaku.

Scholars typically divide the Nara and Heian periods into two categories. The so-called Six Schools of Nara (the Sanron, Hosso, Kegon, Ritsu, Jojitsu, and Kusha sects) were mostly academic schools under state control, centered in Nara, devoted to mastering Buddhist philosophy from China, and to maintaining court patronage. This period is called Nara Buddhism. It was marked by strong court-clergy relations and by lavish state spending on Buddhist temples, images, and texts. It did not show much doctrinal innovation, and was largely devoted to state functions.

In contrast, the Heian era is considered a groundbreaking period. Called “Heian Buddhism,” it centered around the establishment of two new schools -- Tendai and Shingon -- which both played key roles in the Shinto-Buddhist merger. The two founded their monasteries in mountain retreats away from the capital, thus gaining greater autonomy from the court. Both emphasized meditative practices, and taught that everyone had the potential to realize Buddhahood, not just the elite.

|

最澄

Saicho (Saichō)

Founder, Japan's Tendai Sect

Posthumously called

Dengyō Daishi 傳教大師

Daishi 大師 means

"Great Master"

天台

Tendai

Lit. = Heavenly Terrace School

Also called the Lotus Sutra School |

|

Saichō (Tendai) Saichō (Tendai)

and Kūkai (Shingon)

Priest Saichō (767 - 822) founded Japan’s Tendai sect; Priest Kūkai (774 - 835) the esoteric Shingon sect. See sidebar below for more on Kukai. Both schools originated in China, where Saicho and Kukai had traveled to study the teachings. Once transplanted to Japanese soil, both schools flowered with innovation. Saicho’s sect attempted a synthesis of various Buddhist doctrines, including faith in the Lotus Sutra, esoteric rituals, Amida (Pure Land) worship, and Zen concepts. Tendai gained great court favor, rising to eminence in the late-Heian era. Shingon, in contrast, was predominantly esoteric. Its doctrines were mystical and occult, and required a high level of austerity. Elaborate and secret rituals (utilizing mantras, mudras, and mandalas) were developed to help practitioners achieve enlightenment. Despite its complex practices, Shingon exerted a profound impact on religious art and the faith of the court and monastic orders.

Religious pilgrimages were instituted during the mid-Heian era as well, often by priests who had made the arduous sea journey to China, including Saicho, Kukai, Ennin (794 - 864) and Enchin (814 - 891). Pilgrimages became a lasting practice thereafter. At the same time, “Lotus Sutra Meetings” (hokke-e) became popular among the nobility. By the late 10th century, meetings were designed for the salvation of the lower classes. Shinto shrines joined in, adding to the syncretic Shinto-Buddhism of the day. Gatherings for the working class were particularly common in the Kumano region.

Heian Buddhism and Shinto-Buddhist syncretism helped lay the foundation for the widespread propagation of Buddhism among the masses in the Kamakura Era. See From Court to Commoner Buddhism.

|

空海

Kukai (Kūkai)

Founder

Japan's Shingon Sect

真言

Shingon

Lit. = True Word School

弘法大師

Kobo Daishi

(Kōbō Daishi)

Posthumous name

given to Kukai. Daishi means “Great Master”

Mt. Kōya 高野

Japan’s Shingon holy

land is located on and around Mt. Koya. The main temple is called Kongōbuji 金剛峰寺

In 822, Kukai was awarded exclusive control over Tōji Temple 東寺 in Kyoto, making it the center of Shingon practice and worship.

|

|

Kukai (Kobo Daishi) Kukai (Kobo Daishi)

One of Japan’s Most

Beloved Buddhist Saints

Kukai (Kūkai) was the patriarch of the Shingon sect of Esoteric Buddhism. Shingon is Japan’s version of Vajrayana (Tantric) Buddhism. Together with Hinayana and Mahayana, Vajrayana represents one of the three basic forms of Buddhism in Asia today. It is especially strong in Japan and Tibet, and intricately connected with the mandala artform. Shingon’s most prominent deity is Dainichi Buddha, whose symbol is the vajra (thus Vajrayana, the Sanskrit term for Diamond Vehicle).

Posthumously named Kōbō Daishi (the Great Teacher), Kukai remains one of Japan’s most beloved Buddhist saviors -- folklore says he attained Buddhahood before death. Portraits of him abound. The Japanese today tend to ignore doctrinal differences when honoring him. Kukai traveled to China in 804, and was initiated in esoteric teachings by the Chinese priest Huiguo. Kukai returned in 806, and by 816 obtained imperial sanction to construct his monastery on Mt. Koya, a serene location on the Kii peninsula still considered a Holy Land and one of modern Japan's most popular pilgrimage sites.

He played an active role in many fields, performing rituals for the emperor, constructing a large reservoir in Shikoku for the common people, and establishing the first school for common citizens. His legend is riddled with folklore. He is credited with everything from inventing Japan’s kana script to introducing homosexuality. He is one of Japan’s most celebrated calligraphers, and supposedly published Japan’s first dictionary. He became a major patron of the arts, and reportedly founded hundreds of temples across Japan. The Shikoku Pilgrimage to 88 Sites is a popular pilgrimage attributed to Kukai. Most devotees carry a staff bearing the words "we two walk together."

END STORY

An extended version of this story can be found here.

FUTHER READINGS

- Groner, Paul. Saicho: The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School. University of Hawaii Press, 2000 (originally published by University of California, Berkeley, 1984).

- Groner, Paul. "A Medieval Japanese Reading of the Mo-ho Chih-Kuan: Placing the Kanko Ruijii in Historical Context." Japanese Journal of Religious Studies (1995) 22/1-2.

- Faith and Syncretism: Saicho and Treasures of Tendai. Kyoto National Museum catalog, 2005.

- Treasures of a Sacred Mountain. Kukai and Mount Koya. The 1200-Year Anniversary of Kukai’s Visit to Tang-Dynasty China. Tokyo National Museum catalog, 2004.

- Kim, Yung-Hee. Songs to Make the Dust Dance: The Ryojin Hisho of Twelfth-Century Japan. University of California Press, 1994.

|

|