|

|

|

|

This is a side page. Return to Parent Page. This is a side page. Return to Parent Page.

CHRISTIAN INFLUENCE IN JAPAN

Did Christian-Madonna imagery impact Buddhist statuary in Japan? Did mother-babe iconography (Kariteimo, Kannon) develop mostly independently in Japan, despite various “known” influences from China & Christianity? What was the feminization process for Kannon in Japan?

This is a speculative research page, offered here only as a research tool. Some of the topics discussed below have not been fully confirmed, and require further study. This is a speculative research page, offered here only as a research tool. Some of the topics discussed below have not been fully confirmed, and require further study.

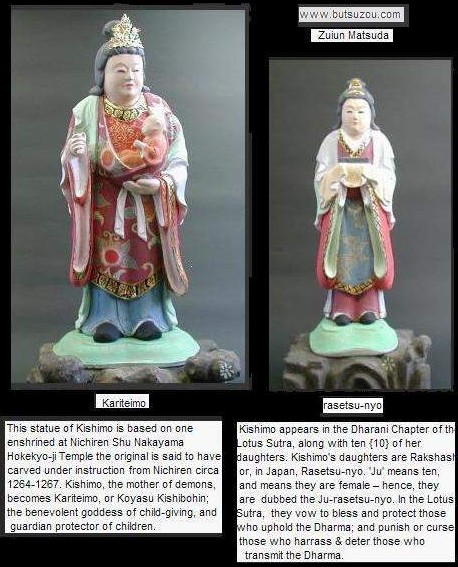

KARITEIMO (JP). HARITI (SKT.) Before becoming a Buddhist goddess, Kariteimo was the mother of demons in Hindu mythology. She symbolizes the selfish nature of mothers who go to terrible lengths to protect their children. Kariteimo had hundreds of children. To feed them, she kidnapped the babies of others and fed them to her own. But, after the Historical Buddha hid one of her children, she came to understand the pain and suffering she had caused countless parents and children. She repented, embraced Buddhism, and became the guardian of children and "child-giving" goddess. Kariteimo is especially important to Nichiren sect, which came to prominence in the Kamakura era, as did images of Kariteimo holding a child. Kariteimo is the Japanese name of the Indian (Hindu) deity Hariti, a protector of children who was the wife of Panchika. In Japan, her name was transliterated as Kariteimo or Karitei, and translated as Kishimojin or Kangimo. In Japan, she is worshipped in monasteries as a protector of the faith and by the general public as a protector of children. She is also -- along with the ten female Rasetsunyo (Hindu lore, female demons who torture and feed on the flesh of the dead, i.e., those who were evil while living) -- considered a protector of the Lotus Sutra and may be painted along with them. Her iconography is based on the script Dai Yakusha Nyo Kangimo Narahini Aishi Joujuhou 大薬叉女歓喜母并愛子成就法. (Note from Mark. I also think she appears in the 26th Chapter of the Lotus Sutra. The same sutra is the main text for Kannon belief in Japan, and is one of the most important Buddhist texts in Japan’s long history with Buddhism). In Japan, there are images of Kariteimo from the late Heian period. She is shown dressed in Sung-dynasty robes and holds a pomegranate in her right hand. She may cradle a child with her left arm and may appear with three, five, seven, or nine children. Examples of her appearance in art include a late-Heian-early-Kamakura-era painting in Daigoji Temple, a Kamakura-period sculpture in Onjouji-Miidera in Shiga prefecture, and a late Heian-to-Kamakura period sculpture in Todaiji, Nara. All three pieces are presented here, on this web page.

In Japan, KICHIJOUTEN is occasionally regarded as a sister of Kariteimo. Kichijouten is also called Kichijoutennyo or Kudokuten (from Sanskrit: Sri Laksmi, Mahasri, Mahadevi). Kichijouten was originally an Indian (Brahman) goddess of fertility, wealth, and beauty. She is linked to Kubera, the Hindu god of the North, and to Vishnu the Lord of Creation. As Vishnu's chief consort, Kichijouten was absorbed later into popular Buddhism in China and Japan.

LEARN MORE

Hariti, Bas-Relief, 9th Century, Borabudur, Java

Photo from: Buddism: Flammarion Iconographic Guides

by Louis Frederic, Printed in France. ISBN 2-08013-558-9, First published 1995

Borobudur. Babe at breast. See upper right of photo.

Photo courtesy www.borobudur.tv/karma_1.htm

|

Kariteimo Holding Babe in Left Hand & Pomegranate in Right Hand. Female Buddhist Deity, Protector of Children, Easy Childbirth. Pomegranate missing due to damage/destruction. Pomogranate is symbol of fertility due to its many seeds. LATE HEIAN ERA (estimate), Wood, Height 42.2 cm, Important Cultural Asset of Japan. Treasure of Todaiji Temple (located in its Kinroujiki Hall), Nara City, Japan. See below caption in Japanese.

|

Close-up of Babe in Arms of Kariteimo.

Same photo as above.

Treasure of Todaiji Temple (located in its Kinroujiki Hall)

|

|

Caption for Above Two Photos |

|

|

ABOVE PHOTOS OF TODAIJI PIECE COURTESY OF:

Handbook on Viewing Buddhist Statues

A wonderful book. Some images at this site were scanned from this book; Japanese language only; 192 pages; 80 or so color photos. By author Ishii Ayako. Click here to buy book at Amazon. ISBN 4-262-156958.

|

|

|

Kariteimo (see Mark’s main page on this deity)

|

Kariteimo is the protector of children and the goddess of easy delivery. Kamakura Era (Early 13th Century), Painted Wood, Height 43.9 cm. Treasure of Onjouji Temple (園城寺, also called Miidera 三井寺) in Shiga Prefecture (Designated an Important Cultural Property). Pomegranate in Right Hand.

NOTE. This temple was burned to the ground numerous times. It may yet turn out that this statue is a reproduction from temple drawings, and therefore the date given may be (as Mir-san says) mistaken. View the Museum Web Page Here (Japanese Language)

|

|

|

Kariteimo - Color on Silk

Treasure of Daigoji Temple (Kamakura Era)

Photo courtesy www.daigoji.or.jp/vihara/reiho/hariti01.html

|

Modern Reproduction

of Kariteimo Painting at Daigoji Temple

Photo courtesy of this Japanese web site.

|

|

ORIGIN OF DAIGOJI TEMPLE. In 874, the Buddhist monk Shobo (posthumous name Rigen Daishi, the Great Master of Holy Treasures) built a hermitage to which statues of Juntei Kannon (Skt. = Cundi, the "mother of the Buddhas"), and Nyoirin Kannon were dedicated on the top of the Kamidaigo mountain, where Shobo discovered a well of spiritual water named Daigo through an inspiration from the local god Yokoo Daimyojin. ENGLISH PAGE: http://www.daigoji.or.jp/e/

|

|

Modern Reproductions of Kariteimo

Available for online purchase at www.butsuzou.com

Above photo montage courtesy:

http://www.fraughtwithperil.com/blogs/rbeck/archives/2005_11.html

COMPARE ABOVE JAPANESE STATUES

WITH BELOW 15th CENTURY MADONNA & CHILD FROM ITALY

1406 AD, by QUERCIA, Jacopo della

http://gallery.euroweb.hu/html/q/quercia/

NOTES ON EARLY CHRISTIAN INFLUENCES IN JAPAN

- Lost Identity, by Ken Joseph; Kobunsha Paperbacks; Explores the arrival of Nestorian Christianity in Japan from the 5th century AD onward and discusses the profound impact of Nestorian Christianity on many Japanese Buddhist traditions. Portions of the book available here in PDF Adobe File. Under Prince Regent Shotoku and Empress Suiko in the seventh century, the Hata people from central Asia were granted full liberty under the provisions of Shotoku’s famous 17-Article Constitution. Some Japanese researchers say that the first bearers of Christianity to Japan were Hata people from modern-day Kazakhstan, who came to Japan from the Silk Road cities of Constantinople, Egypt and Persia starting around 200 A.D. The next wave of Christian immigrants, they say, were the Keikyo people from the (Nestorian) Assyrian Church of the East, who began coming to Japan from the fifth century onwards. In the days of Shotoku Taishi, the Nestorian church grounds at Uzumasa (Japan) had their own "Well of Israel" attached to a David's Shrine, and on the well-spring stood a Sacred Tripod symbolizing the Trinity from which a limpid stream flowed. Visitors to Uzumasa can still see a tripod, build in the style of a triangular torii, which marks the exact spot where the original tripod of the Nestorians once stood. For more details, see the entry in Jaanus Database.

Writes Lauren Arnold:

LA: Greetings from a fellow Guanyin/Kannon aficiando! As an art historian, I have written and lectured about early east/west artistic interaction during the Franciscan mission to China (ca. 1250-1350) and am also doing an entry for Andrea-san on the probable Franciscan origin of the image of the Child-Giving Guanyin in China (see lecture I did on the subject here -- scroll down the page a bit to get to the Guanyin part). The book I wrote on the Franciscan Mission to China is somewhat hard to get (although soon it will be on Google Print).

That said, I am completely fascinated -- and momentarily stumped -- by the wooden sculpture of Kariteimo with the pomegranate that you include with your entry. By my own reckoniong, it is too early for a statue of that sort to be in Japan, but since I also know squat about Japanese art, I sent the Japanese museum website on to Mark Mir at the Ricci Institute of the University of San Francisco (where I am also a research fellow). Mark Mir has done some work in the area and reads Japanese. I questioned him about the translation of the date and this is his reply:

"The Japanese site caption (under the Kanji/Hiragana heading "Kariteimo statue" says: Important cultural treasure: Kamakura Period (first half of the 13th century) [parenthesis in the original]. Next line: Wooden construction ; color (i.e. painted, ploychrome) ; statue height 43.9 cm. So it does say "first-half" of the 13th century. Of course they might be mistaken. Statuary like this usually doesn't last long in Asia, and it must not have an actual date on it, or they would say so. Any old wooden statue is rare in Japan. And I don't find much surviving precedence for this in China, though a Buddhist expert would have more to say about it. It seems to have more direct Indian antecedents than most."

Mark Schumacher Here: Please thank Mir-san for his response. I am encouraged that he referred you back to my web site. However, I don’t fully agree with him. Wooden statuary in Japan, from the Nara and Heian and Kamakura eras, is still quite plentiful. Moreover, since Japan’s 1950 Law for Protection of Cultural Properties, many pieces have been cataloged and registered, and many are clearly -- very clearly -- dated. In restoration and cataloging efforts, many statues were disassembled, and inside were found inscriptions and dates and other smaller religious icons and scripts. Mark Mir is correct in assuming that the date for the Kariteimo piece is only “approximate,” for if they had a date, they would say so. Nevertheless, pieces like this are typically dated based on temple documents and literary references that clearly mention the artwork -- although there are pitfalls to this method of dating, as temples are notorious for “adding” legends to their earlier histories. It’s not a nice thing to say (and this weakens my position), but temples in Japan don’t really care about historical accuracy. Nonetheless, there are at least THREE KARITEIMO PIECES that are dated to the late-Heian-early-Kamakura period -- one at Daigoji Temple, one at Onjouji-Miidera, and one at Todaiji. Photos of all three are shown above.

LA: You'll be amused to know that, for more information on the whole thing, he then referred me back to your website. So, if this statue is from the first half of the 13th century, then it is very like in spirit to images made in France from ca. 1250 on (when the Madonna and Child images became less formal and hieratic, as in Byzantine models, and more motherly, warm, and Franciscan in spirit) -- but in that case it is also earlier and Japanese, to boot. So I'm at a bit of a loss here as to what to say. Somewhere in my vast collection of images I have a Gandharan mother and child image that vaguely compares, but that idea is totally out of whack with the time/space continuum. And, while in my own time I've done my share of academic bungey-jumping, I'm not about to suggest to my colleagues that a Japanese image from the early Kamakura era made its way back to the Ille de France just in time to inspire the Franciscans. Soooooo, maybe we'll have to fall back here on the theme of “universal motherhood," which really means "I don't have a clue." It's a mystery I would love to know the answer to.

LA: By the way, the Jacopo statue is from 1406, so it is 15th century, and the pomegranate in western art stands for the Resurrection (associated with the legend of Persephone, etc.)

M: In Japan, the pomegranate (pronounced “zakuro”) symbolizes fertility due to its many seeds.

|

QUESTIONS AND COMMENTS

ANDREA-SAN AND MARK

A: Although the Lotus Sutra states that Avalokiteshvara/Guanyin can appear in any necessary form, this bodhisattva was represented in Chinese icoography as a rather androgynous male until at least the Sui dynasty (589-618), and it was not until at least the Southern Song Era (1127-1279) that the female Guanyin began to predominate. Now my question is: when did the female form of Kannon begin to appear in Japan? When did it begin to predominate? I see a Chinese influence here. In India, by the way, Avalokiteshvara continued/continues to look male.

M: Yes, all very good points -- points that I am well aware of. It is hard to pinpoint the predominance of the female Kannon in Japan, as the very EARLIEST representations of Kannon already appear feminine -- just look at the Kannon statues at the Horyuji Temple in Nara (the temple associated with Prince Shotoku Taishi). The Kannon treasures here already appear very feminine. These statues were "officially" considered male in gender, but they do not appear masculine.

A: Laura Arnold, an art historian and associate of the Ricci Institute at San Francisco University, has written an entry for Era 5 in which she claims that the Child-bearing Guanyin became part of Chinese Buddhist iconography only after Franciscan missionaries introduced images of the Virgin Mother with Jesus into China in the late Yuan Era (1279-1368), and the art work she produces as evidence is pretty convincing. At least it shows a strong Franciscan impact on the imagery of Guanyin as Child-bearing deity. So my question is: When is the earliest representation of Koyasu Kannon?

M: Very interesting. Could you share a copy of this story with me? Basically, from my reading and understanding, the feminization process of Kannon in Japan began many centuries before that. The circumstancial evidence is strong that Nestorian Christianity (Jp = Keikyo) was already influencing the feminization process by the early Tang era. There is also strong circumstancial evidence that Keikyo immigrants to Japan (already here in the 5th century) influenced the thinking of even Prince Shotoku Taishi, who made a beautiful sculpture of Miroku Nyorai (nude waste up) that is very feminine in appearance, and therefore images of the Virgin Mary may have been known to the Japanese court during this time.

A: I know the Nestorian argument and find it interesting. Indeed, a Nestorian image of what appears to be Madonna and Child was found a few years ago at the site of what was once a 7th-century Nestorian church outside of Xi'an (Changan). I think we might have two Christian influences here, with the latter--the Franciscan--truly pivotal. I have been investigating this for years, talking with leading authorities, and keep finding those nagging but all-so-fascinating uncertainties and ambiguities.

A: In Japan, when is the earliest representation of Koyasu Kannon?

M: In the 8th century, made it is said in the image of the Empress Komyo (or Komei, 701-760). She is the widow of Emperor Shomu and the mother of Empress Koken, who became a Buddhist nun in 749. This feminine aspect of Avalokitesvara (Kannon) contributed greatly to the spread of her cult in Japan. However, it is only from the 14th century, perhaps due to the influence of the Nichiren sect (Kannon as featured in Lotus Sutra), that the people worshipped her statue as a "giver of children." So, if we had to give a provisional date of female predominance, I would say the 13th century. There is also Kariteimo (the demon mother) from the late Heian early Kamakura period. There is also the "Koyasu Monogatari" document of the 14th century. Says Hank Glassman (Haverford College) in “Popular Buddhism and the Efficacy of Narration:”

"Koyasu Monogatari begins and ends with exhortations to its audience to pursue the way of harmony between man and woman, extolling sexual connection as a religious good. The narrative centers on the plight of a pair of twins, a boy and a girl, joined at the torso from armpit to hip, "like the two halves of a folding screen." These children are born to an old nun living at the time of the Gempei wars. She knows them to be a boon, a miraculous gift from King Emma, but they are persecuted by the authorities as "demon children." In the end they are revealed to be the avatars of Buddhist deities, come to shower blessings on the people of the capital. Koyasu monogatari calls the story it tells both auspicious (medetaki) and strange (fushigi). These two qualities are the hallmarks of popular religious literature in medieval Japan."

M: This monogatari does not explain Kannon, but rather the origins of the Jizo hall at Kiyomizu-zaka in the capital, famed for its promise of safe childbirth. Yet, the Koyasu (lit. = easy childbirth) link is very strong. There is a deity named Koyasu Jizo, and others like Koyasu Kannon, Koyasu Kishibojin, and Jibo Kannon.

Koyasu Koujin-sama

Wood, 1543 AD

Koyasu means “Child Giving”

Treasure of Sonbouji Temple 三宝寺, Murayama, Nagano

Designated an Important Cultural Asset

Photo courtesy www.sanbouji.com

Sanboui Temle is a Jodo-sect temple

There are many Koyasu forms in Japan, but Koujin-sama

is rarely shown in this fashion or with this iconography.

Nevertheless, the connection of Koujin with the kitchen and home

is perhaps the main reason for this particular Koujin manifestion.

A: By the way, the image of the Lactating Virgin goes far back into Christian iconography. I know of a fifth-century Coptic image that was probably borrowed from the image of Isis nursing Horus. Is there any possibility that the nursing Kannon had a Christian predecessor or inspiration in Japan?

M: Unknown, but not impossible. The Nestorians did worship Mother Mary, but they did not worship her as the "mother of god." It is only "assumed" that Prince Shotoku learned about the Mother Mary. There is no "hard" evidence yet.

RESOURCES ON MARIA-KANNON LINKAGE:

|

|