|

|

|

|

THIS IS A SIDE PAGE

Click Here to Return to

Main Tennin / Tennyo / Apsara Page

NOTES ON CHINA’S DUNHUANG CAVES

PHOTOS OF CHINA’S APSARAS (9 PIX)

敦煌 (Jpn. = Tonko; WG = Tun-huang; PY = Dunhuang)

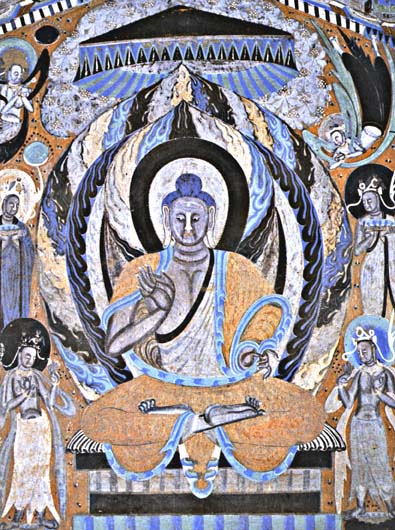

Music Bosatsu of the Chinese Mogao Grottoes

Wall Paintings of Dunhuang (Jp. = TONKO NO HEKIGA)

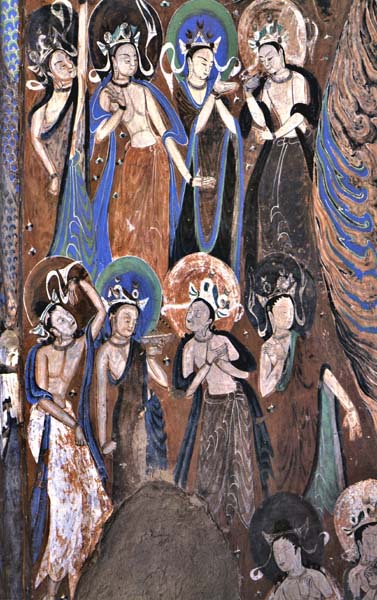

Apsaras Murals from Western Wei (Dunhuang)

Photo Courtesy Washington.edu

Below text courtesy Soka Gakkai Dictionary

敦煌 (Jpn. = Tonko; WG = Tun-huang; PY = Dunhuang)

An oasis town located in the western end of the so-called Kansu Corridor, in the present-day northwestern Kansu Province, China. Formerly called Kua-chou or Shachou. It was a meeting point of two branches of the Silk Road running north and south around the Tarim Basin, and a place of entry into China as well as the starting point from China toward the "western regions." Today it is particularly well known for the religious, cultural, and artistic treasures preserved there in the form of painting and sculpture in its Mo-kao (Mogao) Caves, which are also known as the Caves of the Thousand Buddha. Buddhist artwork found therein dates back to the 4th century AD.

In ancient times, Tun-huang was ruled by a tribal confederation called the Yueh-chih and then by the Hsiung-nu, known to Europeans as the Huns. During the reign of Emperor Wu (r. 141-87 B.C.E.) of the former Han dynasty, Tun-huang was brought under Chinese rule. From early on, Tun-huang was an important center for trade between East and West. In the first and second centuries, Buddhism was transmitted to China from India and Central Asia. By the third century, Tun-huang was not only a route of this transmission, but was itself a great center of Buddhism. Buddhist monks from India and Central Asia made sojourns to Tun-huang. The monk Dharmaraksha, who lived in the third and fourth centuries and translated the Lotus and other sutras into Chinese, came from this area and was called the Bodhisattva of Tun-huang. In the fifth century, the Indian monks Dharmaraksha (385-433) and Dharmamitra (356-442) came to this area and stayed for some time to preach. Many priests who traveled from China seeking Buddhist teachings also stopped in Tun-huang en route to India and Central Asia.

Apsaras playing music

Photo courtesy www.imperialtours.net

Tun-huang, for the most part, remained under the rule of the various Chinese dynasties. In the 780s, however, it fell under Tibetan dominance, which lasted for approximately sixty years. As a result, in Tun-huang, Tibetan Buddhism and Chinese Buddhism encountered and influenced each other. Thereafter Tun-huang was at different times placed under the rule of the Chinese, the Tangut (the people of the Hsi-hsia kingdom, which existed in northwestern China from the early eleventh through the early thirteenth century), and the Mongols. The Mo-kao (Mogao) Caves, southeast of Tun-huang, number about five hundred and are located at the base of the eastern side of a hill called Ming-sha-shan. In 366 the first cave was carved from the cliff side and the construction of others continued thereafter. These caves preserve wall paintings that portray events in Shakyamuni Buddha's life and also the Jataka, stories of the previous lives of the Buddha.

Early in the twentieth century, a large number of ancient manuscripts and documents as well as paintings and other pieces of artwork were found in one of the caves. Among them were numerous manuscripts of Buddhist scriptures, dating from the fifth to the eleventh century. Other items included Taoist, Confucian, Manichaean, and Nestorian scriptures. In addition to these religious documents, there were many ancient secular documents concerning government, economics, and literature. These records have been important to the study of Chinese social history during that period. The scriptures and documents were written in Chinese, Brahmi script, Tibetan, Khotanese, Kuchean, Sogdian, Turkish, Uighur, and the writing system of the kingdom of Hsi-hsia. <end quote Soka Gakkai Dictionary >

The Dunhuang Texts

Below text courtesy this site.

Today, more than a century after the discovery, the texts are popular primary sources for scholarly study all over the world, so much so that "Dunhuang Studies" has emerged as its own research discipline. Experts have dated some of the Dunhuang Cave documents to only 500 years after the Buddha's death, making them among the oldest texts of their kind. The Dunhuang manuscripts are housed in four major institutions: the National Library of China, the British Library, the National Library in France, and the Institute of Oriental Studies in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Below text & photo courtesy of China.org.cn

STORY TITLE: Dunhuang “Apsaras” Instruments Debut

Story by Chen Lin and Daragh Moller

First Published: November 27, 2003

Flying Chinese Apsaras: Mythic fairies dancing and playing celestial music is a common tableau from the Dunhuang fresco. But what were the ancient musical instruments like and could they be replicated? A reporter from Star Daily went to the opening of the first "Dunhuang Fresco Instruments Show" at the Huating Mansion in Beijing to find out and saw 180 replicated musical instruments from the spectacular frescos. Zheng Ruzhong, an expert from the Dunhuang academy says, "Dunhuang culture is extensive but most people just understand it from the flying Apsaras, but it's really far more than that." Flying Chinese Apsaras: Mythic fairies dancing and playing celestial music is a common tableau from the Dunhuang fresco. But what were the ancient musical instruments like and could they be replicated? A reporter from Star Daily went to the opening of the first "Dunhuang Fresco Instruments Show" at the Huating Mansion in Beijing to find out and saw 180 replicated musical instruments from the spectacular frescos. Zheng Ruzhong, an expert from the Dunhuang academy says, "Dunhuang culture is extensive but most people just understand it from the flying Apsaras, but it's really far more than that."

In the exhibition, there are all kinds of instruments -- including wind, stringed, and percussion instruments, in which many have never be shown to the public. Except for the pipa (balloon guitar), a famous ancient instrument in China, most are unfamiliar to ordinary people. It's said that many folk instruments have been lost but can still be seen in the records of history.

Zhang Yongjun, the sponsor of this exhibition, said they''d been preparing for this exhibition for many years. The Dunhuang music instruments study and duplicate began early in 1988. The "Dunhuang fresco instrument study and duplicate project," which was sponsored by the Dunhuang academy, was appraised by an 18-person appraisal committee after an excellent performance with 54 duplicated instruments. In the last 11 years, experts of the 54 instruments have duplicated 180 instruments in 44 groups, and studying and duplication has now finished.

According to experts, in the 492 Mogao grottoes, there are 240 dance and music grottoes. The frescoes there show 4,000 instruments in 44 groups, 3,000 performers, and 500 groups of bands of all kinds. Zheng said that this is not only an exhibition -- they also invited many musicians to perform on the instruments in order to show the differences and similarities of ancient and contemporary music. Many of the instruments were made of expensive material - a rosewood zither cost 10,000 yuan.

In addition to this exhibition, the sponsor said they would hold a performance outside the Mogao Grottoes with instruments and replica costumes from the fresco. The performance will include ancient music that revives the songs and dances of thousands of years ago. It will be held on August 22, next year. <end story by China.orn.cn)

Apsaras Murals from Western Wei (Dunhuang)

Photo Courtesy Washington.edu

Apsaras Murals from Western Wei (Dunhuang)

Photo Courtesy Washington.edu

Below text courtesy The Japan Times

First Published Saturday, March 18, 2000

Story Title: Distant Echoes from a Desert Lute

By staff writer Alexander MacKay-Smith IV

"We are not reviving the original music of over 1,000 years ago," says Sukeyasu Shiba, director of the leading independent gagaku (court music) group Reigakusha, which will present a concert March 23 (2000) of music from over 1,000 years ago.

Shiba has spent decades studying the oldest sheet music in the world, preserved in the cave temples of Dunhuang in western China and in Japanese archives, including the documents stored in the Shosoin in Nara since the 8th century. His studies have yielded questions as well as answers, and in the end, he says, we still cannot be sure what the music of Tang China and its cultural satellite, Heian Period Japan, really sounded like.

Still, he has the instruments: reproductions of those found in the Shosoin, made (at great expense) after intensive study of the precious originals, the oldest surviving musical instruments in the world. "I just wanted to know what they sounded like," Shiba says.

He has a right. Scion of a family that has been in hereditary service to the Emperor as gagaku musicians since the instruments were first put into the Shosoin (around 756, with some additions a century later), Shiba joined the Imperial Household Agency gagaku orchestra as a teenager, graduating from their training school in 1955, specializing in flute, biwa (lute) and dance. He has won numerous awards, including the Minister of Education Prize in 1987 and, in 1999, the Medal with Purple Ribbon, awarded by the Emperor himself for achievement in culture.

Shiba's work in gagaku has covered a wide range, from new compositions by modern composers like Toru Takemitsu (and Shiba himself) through all the Imperial orchestra's standard repertory. The effort to reconstruct the works that have dropped out of the standard repertory over the centuries, however, has particularly engaged his attention. Although scholars from Oxford to Beijing are hard at work on the ancient tablatures, Shiba has done most to let them be heard -- within the limits of reconstruction.

Apsaras playing music www.imperialtours.net

Dunhuang Cave

Photo Courtesy Expatsinchina.com

Possibly feeling constricted by the conservatism of the Imperial Household Agency, in 1984 he resigned and founded Reigakusha to make gagaku available to wider audiences, explore new music for the instruments and strive to reconstruct the old.

The upcoming concert, "Saiiki no Hibiki (Echoes from the West)," features extracts from the Dunhuang Lute Tablature (Tonko Biwafu), part of the immense hoard of books and documents famously found in 1900, walled up in back of a Buddhist cave temple in the old Silk Road desert city of Dunhuang.

Discovered by a monk named Wang Yuanlu, the documents (a whole library of thousands of documents, printed books and manuscripts in a dozen languages, ranging from Buddhist sutras to bills of lading) were apparently hidden sometime in the 11th century, ahead of an impending invasion, but it includes much older material. Most of it was bought up by French scholar-explorer Paul Pelliot in 1908, taken back to France and subsequently published in facsimile form. Deciphering and studying the materials has occupied scholars around the world ever since, and probably will for generations to come.

The great Japanese musicologist Kenzo Hayashi (1899-1976) established that the Dunhuang Lute Tablature was essentially the same notation system as that used since Nara times for gagaku biwa music in Japan. Hayashi launched, and for years dominated, the study of this material in Japan. Shiba speaks of him with respectful affection, but he has moved beyond Hayashi's work.

"Hayashi sensei was a scholar," Shiba emphasizes. "I am a musician." The notes of the Dunhuang tablature are understood well enough, but they don't seem to add up to much of a melody. Shiba has proceeded on the assumption that, as in modern gagaku performance, the biwa provided chords to support a melody carried by the flutes and hichiriki reed pipes (a wider range of which were used in those days).

There is much dispute in the musicology world as to the validity of the reconstructions. Many Western scholars have taken a different approach, disregarding the Japanese performance tradition in favor of studying the original documents only.

Still, Japanese scholars feel a proprietary interest in the old tablatures. The music they represent died out utterly in China sometime around the 13th century; modern Chinese music uses different instruments and different principles. Only in Japan was the music of Tang handed down by a continuous chain of transmission. Their interpretations, they insist, are valid.

There has been loss, to be sure, and change. Many pieces are no longer performed, and instruments have fallen out of use. Performing style has changed. Anyone who has sat through a gagaku performance must have been nagged by the suspicion that in Prince Genji's time the music was rather more sprightly. Shiba cheerfully agrees.

"At least twice as fast," he grins. Centuries of respect verging on awe resulted in ever-increasing solemnity, and ever-slower tempos. Performers responded by elaborating the melodic line with delicate nuances. To Shiba the musician, though, the instruments are the key. Whatever the reconstruction of the written music, at least we can play the instruments, we can hear what they sounded like.

Reigakusha's concerts offer the chance to hear some of them: the kugo harp; the haisho panpipes; the five-string lute; large versions of the sho mouth organ and hichiriki; and others. As Shiba says, the music may not be exactly the same, but just to hear the sound of the ancient instruments is to feel a connection with the glories of Tang and Heian.

"Saiiki no Hibiki," Sukeyasu Shiba and Reigakusha, 7 p.m. March 23 (2000) at Yotsuya Kumin Hall (Yotsuya Kumin Center 9F), five minutes' walk from Shinjuku Gyoen-mae subway station. Admission 1,500 yen in advance, 2,000 yen at the door. For information and reservations call Reigakusha (03) 5269-2011. < end story from The Japan Times: March. 18, 2000 >

QUICKTIME PANORAMA

CLICK HERE FOR THE PANORAMA MOVIE

Click and drag within the image to view the panorama.

You'll need to install Quicktime (free) to view above panorama.

360-Degree Rotating Image of Dunhuang Cave #285

Source: buddhist-art.arthistory.northwestern.edu/fraser/d285.html

Photos by Dunhuang Wenwu Yanjiusuo of the Dunhuang Cultural Relics Research Institute.

Zhongguo shiku, Dunhuang Mogaoku [Chinese Caves, Dunhuang Mogao Caves]. Beijing: Wenwu, 1989.

LEARN MORE

- Tennin and Tennyo.

Celestial Maidens in Japanese artwork. This site.

- Tenbu (Deva) Main Menu. This site. Lists nearly 80 deities.

- Bosatsu on Clouds Byoudou-in Temple, Japan. This Site.

View the beautiful sculptures of Flying Apsaras at Byoudou-in.

- Apsaras at Dunhuang (China)

Please see Gabi Greve’s page for many more photos of the Apsaras paintings found in the caves of Dunhuang, China. Outside link.

- Apsaras appear often in the stone carvings at the Angkor Watt ruins in Cambodia. Visit this outside link for a few photos.

- Definition of Apsaras from Wikipedia

Apsaras, in Hindu and Buddhist mythology, are the celestial damsels of Indra's court, created by Lord Brahma. Natya Shatra lists the following Apsaras: Manjukesi, Sukesi, Misrakesi, Sulochana, Saudamini, Devadatta, Devasena, Manorama, Sudati, Sundari, Vigagdha, Vividha, Budha, Sumala, Santati, Sunanda, Sumukhi, Magadhi, Arjuni, Sarala, Kerala, Dhrti, Nanda, Supuskala, Supuspamala and Kalabha. <source = Wikipedia>

- Apsaras in Sanskrit means “essence of the waters.”

It can also mean “moving in or between the waters.”

The Apsaras are divine beauties, dancers of the gods,

said to dwell in Svarga, the paradise of Lord Indra.

Mogao Caves Mogao Caves

A Clash Of Civilizations

Story by Guy Rubin

www.imperialtours.net #1

www.imperialtours.net #2

- Asparas Paintings in

the Dunhuang Caves.

Very excellent.

Photos appear above,

on this web page. But many more appear on the below site:

http://depts.washington.edu/chinaciv/bud/5dunrev1.htm

THIS IS A SIDE PAGE

Click Here to Return to

Main Tennin / Tennyo / Apsaras Page

|

|