|

|

|

|

This is a Side Page

Return to Main Benzaiten Page

LINKS. Maroon = jumps inside this page; LINKS. Maroon = jumps inside this page;  = jumps to other page at this site; = jumps to other page at this site;  = jumps to external site = jumps to external site

|

BENZAITEN'S MAIN SANCTUARIES IN MODERN JAPAN

|

Benzaiten is modern Japan's preeminent water goddess, one worshipped independently and as one of Japan's Seven Lucky Gods of wealth and good fortune. Her temples and shrines are, befittingly, nearly always in the neighborhood of water -- the sea, a river, a lake, or a pond. Among the myriad sanctuaries devoted to her, the three most widely known today are those at Enoshima (near Kamakura), Itsukushima (Miyajima, Hiroshima), and Chikubushima (Lake Biwa, Shiga) -- all islands. The three are collectively known as the Three Great Benten Sanctuaries (Nihon Sandai Benten 日本三大弁天), where she grants wishes for all manner of mundane concerns and protects those who ply the waterways. Nationwide, she is worshipped for spiritual and material gains by monks, nuns, musicians, painters, performers, sculptors, writers, jealous women (see popup note)POPUP NOTE (PN):

Some, like author Chiba Reiko , say Uga Benzaiten is a jealous deity, that her jealousy is indicated by the white sakes coiled around her. Chiba also says court musicians who played the biwa in Japan's medieval period remained single, for if they married, they feared they would incur the wrath of Benzaiten, who would take away their musical ability. Today, says Chiba, married couples who pray to Uga Benzaiten for a beautiful daughter are told to worship separately, never as a couple -- supposedly, if they worship Benzaiten at the same time, they will become separated. In Japanese folk traditions even today, Benzaiten is said to be a jealous deity, one identified with many curious practices and taboos that, if not followed, will lead to the breaking up of loving couples or happily married people. , and many others, for she serves as the Goddess of Learning, Oral Eloquence, Music, Poetry, Speech, Rhetoric, Wealth, Longevity, one who can end droughts or deluges (and is thus said to control dragons), one who can protect the nation against natural disaster, and one who protects warriors and brings victory on the battlefield.

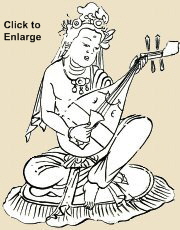

Benzaiten playing biwa. Her most common form in Japan.

From the 12th-century Japanese text Besson Zakki 別尊雑記

(Miscellaneous Record of Classified Sacred Images)

Below we present some of her major strongholds in Japan. The ranking of Benzaiten's sanctuaries has changed over time. The 14th-century Japanese text Keiran Shūyōshū lists six Benzaiten strongholds -- (1) Tenkawa 天河 or Amanogawa 天川, present-day Nara Prefecture; (2) Itsukushima 厳島, present-day Hiroshima Prefecture; (3) Chikubushima 竹生島, present-day Shiga Prefecture; (4) Enoshima 江の島, present-day Kanagawa Prefecture; (5) Minō 箕面, present-day Osaka Prefecture; and (6) Sefurisan 脊振山, present-day Saga Prefecture. The first three were considered the most important in olden times, and were said to be linked together by an underground tunnel. <soucre: Watsky p. 55-56> In modern times, there is a grouping called the Five Great Benten Sanctuaries (Nihon Godai Benzaiten 日本五大辯財天), consisting of the aforementioned Three Great Benten Shrines ( Enoshima, Itsukushima, Chikubushima) along with Tenkawa and Kinkazan Island 金華山 (near Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture). Four are located on islands; Tenkawa alone is near a river. <sources: Upendra Thakur. 1992, p. 36 and Benzaiten scholar Catherine LudivkQuoted From:

Catherine Ludvik, 15th Asian Studies Conference Japan (ASCJ), International Christian University (ICU), 25 June 2011. Presentation entitled Benzaiten and Ugajin: The Skillful Combining of Deities. (Session 16: Room 253).

Other Writings by Ludvik

From Sarasvati to Benzaiten (India, China, Japan). Ph.D. dissertation. University of Toronto, January 2001. South and East Asian Religions. Winner of the Governor General's Gold Medal 2001. Also see Sarasvati Riverine Goddess of Knowledge: From the Manuscript-Carrying Vina-player to the Weapon-Wielding. 2007. 374 pages. Drawing on Sanskrit and Chinese textual sources, as well as Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist art historical representations, this book traces the conceptual and iconographic development of the goddess of knowledge Sarasvati from some time after 1750 B.C.E. to the seventh century C.E. Through the study of Chinese translations of no longer extant Sanskrit versions of the Buddhist 'Sutra of Golden Light' the author sheds light on Sarasvati's interactions with other Indian goddess cults and their impact on one another. Also see La Benzaiten a huit bras: Durga deesse guerriere sous l'apparence de Sarasvati," Cahiers d'Extreme-Asie, no. 11 (1999-2000), pp. 292-338. Also see Metamorphoses of a Goddess. Kyoto Journal KJ #62, 2006

Also see Uga-Benzaiten: The Goddess and the Snake, pp. 95-110.

Impressions, The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 33, 2012. > Says Chaudhuri: "The Edo Meishoki 江戸名所記 (1836) by Saitō Sachio and others documents a fairly good picture of Sarasvatī [aka Benzaiten] worship in the Tokyo area in the 19th century. Judging from the large number of entries and references on Sarasvatī in the guidebook, she appears to have been the most popular Hindu deity in and around the city." <end quote; see pages 50-51> Chaudhuri then goes on to describe three Sarasvatī shrines, including Kanamejima Benzaitensha (Shingon, near Haneda Airport), Seto Benzaiten (near Kamakura), and Inogashira Benzaitengu (Tendai, near Tokyo). When the government forcibly separated Shintō and Buddhism in the latter half of the 19th century, many Benzaiten sanctuaries and icons were dismantled and replaced with Shintō-Kami-only counterparts. However, in the post WWII era, Benzaiten has staged a comeback at many of her former sanctuaries. Based on a 1976 analysis of well-known shrines and their branch shrines by Okada Yoneo 岡田米夫 (1908-1980), shrines associated with Benzaiten are still among the most popular -- Itsukushima and Munakata shrines, for example, are the 5th most widespread nationwide, numbering around 8,500. <source: Kokugakuin Univ.; for a chart click here; also see Handy Bilingual Reference for Kami & Jinja (2006)>

|

|

|

Chikubushima Shrine 竹生島神社 (Bamboo Grow Island)

also known more recently as Tsukubusuma Jinja 都久夫須麻神社

Address: Shiga Prefecture, Lake Biwa, Nagahama City, Hayazaki-cho 1665

Official Site: chikubusima.or.jp (J-site), TEL: 0749-72-2073

English Resources: chikubushima.jp/e_origin

|

|

|

Eight-Armed Benzaiten Playing Biwa

and Holding Sake Cup & Sake Flask

Modern, early 21st century

By artist Suzuki Seishō 鈴木靖将

From brochure by sake brewer

Ikemoto Shuzō 池本酒造 (Shiga)

Also see image of Azaihime.

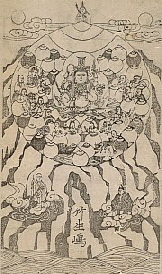

8-Armed Uga Benzaiten of Chikubushima, Surrounded by 15 attendants, numerous wish-granting jewels, and other deities. Edo era, 19th century. Woodblock print; ink on paper. H = 41.4 cm, W = 24.3 cm. Photo the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

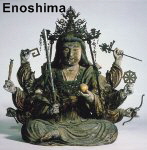

8-Armed Uga Benten, Chikubushima 竹生島, Shiga Pref. 滋賀県. Wood, dated to 1565. Photo John Dougill

Snake at Chikubushima

Photo Photo John Dougill

Modern Votive Tablet (Ema 絵馬)

Photo this J-site

|

|

One of the Three Great Benten Sanctuaries (Nihon Sandai Benten 日本三大弁天) in Edo-era Japan and in modern times, as well as one of Benzaiten's six strongholds as reported in the early 14th-century Japanese text Keiran Shūyōshū. Located at the northern end of Lake Biwa 琵琶湖 (Shiga Pref.), Chikubushima is one of Benzaiten's oldest island sanctuaries in Japan, but Benzaiten did not become the central deity here until sometime in the late Heian period.

Says scholar Sarah Alizah Fremerman:REFERENCE:

Fremerman, Sarah Alizah, Divine Impersonations: Nyoirin Kannon in Medieval Japan, Ph.D. Dissertation, Stanford University, 2008, 230 pages; AAT 3332823. Available at Proquest. Also view online using Google Books. "Long before Benzaiten's arrival, the water kami Azai-hime-no-mikoto was worshipped here to insure the safety of water traffic on the lake. In the Nara period the island was an important site for itinerant monks practicing austerities. From the Heian period onward Benzaiten took her place here as the 'original form' of the local kami. Benzaiten is said to dwell high on the island, while the local dragon god dwells in the depths of the lake." <end quote> The island's mythical origins are recorded in various old Japanese texts, including the now-lost 8th-century Ōmi no Kuni Fudoki 近江国風土記 (Records of the Culture and Geography of the Ōmi Province). According to this text, the kami Tatamihiko no Mikoto 多多美比古命 of Mt. Ibuki 夷服岳 (伊吹)competed for height with Azaihime no Mikoto 浅井姫命 of Mt. Azai 金糞岳, but he lost, and in a fit of anger he cut off her head, which fell into the lake and became Chikubushima Island. Another legend attributed to the Ōmi no Kuni Fudoki says when the lopped-off head began to sink, it made the sound "tsuku tsuku," hence the island's alternative name Tsukubujima. In the 931 CE and 1415 CE versions of the Chikubushima Engi 竹生島縁起 (Legends of Chikubu Island), we hear a slightly different story. Writes scholar Andrew Mark Watsky in Chikubushima: Deploying the Sacred Arts in Momoyama Japan, p. 51): "When there occurred a contest of strength between the brother and sister deities Ibukio no Mikoto and Azaihime no Mikoto (the kami now enshrined in the Tsukubusuma Main Hall), Azaihime no Mikoto lowered herself in the northern part of Lake Biwa. She solidified the water's spray to form a rocky shore and piled the wind-borne dust to create an island; she commanded fish to pile stones at the island to form a spit of land and called on birds to scatter the seeds of various trees. Bamboo, we are told, was the first thing to take root there, and so the name of the island came to be written with the characters for 'bamboo' and 'grow' (chiku 竹 and bu 生), and to be read as Chikubushima. <end quote> In Japan's famous medieval epic Heike Monogatari 平家物語, Taira no Tsunemasa 平経正 (a famous poet and musician) visits Chikubushima, where he kneels and declares Daibenkudokuten (one of many Benzaiten forms) to be the "bringer of salvation for sentient beings.....those who worship here even once will have every wish granted." When Tsunemasa later played the biwa in her sanctuary, the goddess was so moved she appeared to him above his sleeve in the form of a white dragon. < see passage in Tale of Heike>. Both the Genpei Jōsuiki 源平盛衰記 and the Sankō Genpei Jōsuiki 参考源平盛衰記 (also dated to the medieval periodEra Names & Dates:

Standard dating scheme found in both Japan and the West.

- Ancient refers to the Asuka and Nara periods (538-794)

- Classical refers to the Heian period (794-1185)

- Medieval refers to the Kamakura era (1185-1333), Muromachi era (1336-1573), and Edo era (1600-1867)

- Modern refers to everything since 1868 (Meiji, Taisho, Showa, & Heisei periods)

NOTE: Ancient & Classical are sometimes used collectively to refer to everything through the Nara era. The Edo Period is also known as "Early Modern," while Meiji and after are the "Modern" period. The term "Premodern" refers to pre-Meiji. ) mention the appearance of Benzaiten during Tsunemasa's pilgrimage. The manifestation came in the form of a white fox jumping down from the altar. <Chaudhuri, p. 155; Minobe pp. 215-216> Also see English translations of this story in the Heike Monogatari by A.L. Sadler (Google Books) and by the Asiatic Society of Japan (1918). In the latter, jump to Chapter Two for the story of Tsunemasa and the white dragon. The 18th-century text Ōmiyo Chishiryaku 近江輿地志略 presents the story of the origin of Chikubushima Shrine, in which Benzaiten appears before Emperor Kinmei 欽明天皇 (509-571) and tells him that she is a manifestation of the Sun Goddess Amaterasu, the spirit of the sun, and the spirit of wealth and social standing on earth. On the first day of the serpent in the month of the serpent she descends to earth and brings happiness to the people, and on the first day of the boar (hog) in the month of the boar, she ascends to heaven and nurtures the heavenly beings. <Chaudhuri, p. 46> During the forced separation of Buddhism and Shintoism in the latter half of the 19th century, objects associated with Benzaiten were replaced with Shintō items -- with Azaihime no Mikoto regaining her status as the central focus of veneration. But Benzaiten has since staged a comeback. Today the main devotional deity at the island's Shingon-sect Hōgonji Temple 宝厳寺 is once again Benzaiten, while the nearby Tsukubusuma Jinja Shrine 都久夫須麻神社 (aka Chikubushima Jinja) pays homage to Azaihime, Ichikishima (aka Benzaiten), food kami Uga-no-mitama, and Ryūjin 龍神 (Dragon King). Watsky says the name Tsukubusuma was a 19th-century concoctionion for renaming the island's main Benzaiten Hall. On page 42, Watsky writes: "Its present name -- the Tsukubusuma Jinja Honden (Tsukubusuma Shrine Main Hall) -- is a nineteenth-century fabrication. It was conferred in 1871 as part of the new national policy to separate Shinto and Buddhism: the Shiga prefectural government declared the building [the Benzaiten Hall] to be Shinto and ordered that it be called by the Shinto name Tsukubusuma Jinja in place of the one then used, Benzaitensha. Objects associated with Benzaiten were replaced with Shinto ceremonial implements, and the kami Azaihime no Mikoto was made the new focus of worship.......the invented name is still used today, and Benzaiten's ritual objects remain exiled from their historical home, obscuring the pre-Meiji character of the building (and also of the thoroughly interwoven Shinto and Buddhist ritual activities of the island)." <end quote> Chikubushima's central event is the annual Lotus Festival (Renge-e 蓮華会) in mid-August, when the island celebrates the powers of Benzaiten. The festival traces its origins back to the medieval period, when the Chikubushima chapter of the Lotus Flower Society (also called Renge-e 蓮華会) prayed to Benzaiten for rain. Each year a new statue of Benzaiten was (is) commissioned and installed within Hōgonji Temple. Dozens of these statues are still extant and on display in the interior corridors of the temple. Chikubushima's Hōgonji Temple is also the 30th site in the 33-Site Saigoku Kannon Pilgrimage 西国三十三観音霊場 in Western Japan.

Learn More

|

|

Enoshima Jinja, Enoshima Shrine 江島神社

more popularly known as Enoshima Benten 江ノ島弁天

Address: Enoshima 2-3-8, Fujisawa City, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan 251-0036

Official Site: enoshimajinja.or.jp (J-site), TEL: 0466-22-4020

English Resources: Kondo Takahiro's Kamakura Guide

|

|

|

Ofuda 御札 (charm, talisman)

at Enoshima Benten. Modern.

Naked Benten, aka Myō-on Ten

妙音天, at the Hōan-den 奉安殿 on Enoshima Island. H = 55 cm. Dated to the Kamakura period. Learn more.

Happi Benzaiten (8-Armed Benten).

At the Hōan-den 奉安殿, Enoshima. Kamakura Era. Learn More.

At Enoshima, Benzaiten is associated

with a turtle -- in various Japanese

tales, turtles act as the main

messengers of the dragon kings.

For details see Turtles.

3 Dragon Scales = Hōjō Family Crest

|

Dragon-Snake of Enoshima & the Hōjō Clan (Regents of Kamakura). According to a story appearing in the Japanese text Taiheiki 太平記 (circa 1371), Hōjō Tokimasa 北条時政 (1138-1215), the first Hōjō regent of the Kamakura shōgunate, visited a cave on Enoshima Island. He prayed to the dragon (serpent) living in the cave to grant prosperity to his clan. The wish was granted, and even today a dragon statue is enshrined in the cave. As a token of this promise, the dragon left behind three scales, which are reportedly the origin of the three triangles of the Hōjō family crest, known as the Mitsu Uroko 三つ鱗 (three scales). Today this emblem can be clearly seen on the gates to Hōkaiji Temple 宝戒寺 in Kamakura, a temple built by order of the Ashikaga Shogunate in 1335 CE to pacify the souls of the defeated Hōjō clan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of the Three Great Benten Sanctuaries (Nihon Sandai Benten 日本三大弁天) in Edo-era Japan and in modern times, as well as one of six Benzaiten strongholds as reported in the early 14th-century Japanese text Keiran Shūyōshū. Located on the island of Enoshima 江の島 in Sagami Bay, about 50 kilometers south of Tokyo and only seven kilometers from Kamakura. Enoshima was initially dedicated to the three Munakata kami goddesses of islands, with Tendai monk Ennin 円仁 (794-864) credited with enshrining Ichikishima-Hime (the most important of the three) here in 853 CE. Benzaiten was introduced to the island sometime later. She, along with a dragon, figure prominently in the Enoshima Engi 江嶋縁起, a history of Enoshima written in 1047 CE by the Japanese monk Kōkei 皇慶 (also read Kōgei; 977-1049). See story below. Enoshima became an extremely popular shrine-temple multiplex in the 18th and 19th centuries, thanks not only to its proximity to Edo (Tokyo) but also because it offered spectacular views of nearby Mt. Fuji, one of the nation's most sacred peaks. In period artwork, Enoshima appears in over 200 Ukiyoe 浮世絵 (woodblock prints). With the forced separation of Buddhism and Shintōism (Shinbutsu Bunri 神仏分離) in the early Meiji period (1868-1912), Enoshima elected to join the Shintō camp and was therefore obliged to purge itself of Buddhist influences, which included its Benzaiten icons. Let us note, however, that Ichikishima-hime (one of the Munakata Trio) had many centuries earlier been identified as a kami manifestation of Benzaiten, and hence she served as a stand-in during Benzaiten's absence.

The religious reforms following WWII allowed Benzaiten to stage a comeback. "At the jinja," says scholar Richard Thornhill in Sarasvati in Japan, "there are two statues of Benten, both more than 600 years old, of which one is unclothed and the other eight-armed. The unclothed Benten is milk-white, plays a biwa, and is carved in great detail. She is popular with female entertainers, such as geishas in the past and actresses and pop singers today. The eight-armed Benten holds a sword, a dharma wheel and various other items found in Hindu iconography." <end quote> During the forced separation of Buddhism-Shintōsim, however, Enoshima's Benzaiten icons were "dumped into a corner" of a hall dedicated to Ichikishima-hime and "local children played with them." <quotes from Kondo Takahiro> When Benzaiten was restored after the war, the famous nude statue was missing its left hand, left leg, and right ankle (see photo). These had to be replaced. Today both statues are on public display in an octagonal hall known as Hōan-den 奉安殿 (see photos at right), but for most of their history, the two statues were hidden from the public gaze and exhibited only once every six years (in the year of the snake and year of the boar), said to be especially effective times to worship this divinity.

As for the 8-armed Benzaiten statue at Enoshima, the Azuma Kagami 全訳吾妻鑑, an official Japanese record of the Kamakura era describing events between 1180 and 1266, says the famed warrior Minamoto Yoritomo 源頼朝 (1147-1199) sought divine assistance from Benzaiten at Enoshima. Minamoto reportedly asked the Buddhist monk Mongaku 文覚 to make this statue to curse his enemies. Since the Edo period, it has been prayed to by samurai seeking protection on the battle field and victory in war. After Minamoto's invocation of the deity and the installation of the statue, the complex came to be called Kinkizan Yoganji Temple 金亀山与願寺. Says independent researcher Kondo Takahiro: "Minamoto named it Kinkizan Yoganji, a Shingon-sect Buddhist temple.......It was founded as a sub-temple of Ninnaji Temple 仁和寺 in Kyoto. To the newly enshrined Benten, he prayed for victory over the Fujiwara clan, that was then powerful and grew near to rivaling the Minamoto up in Hiraizumi 平泉, Iwate Prefecture, in the northern part of Honshu. Yoritomo's prayer was answered. With his victory over the Fujiwara clan in 1189, the Benten goddess was reputed for her ability to fulfill the wishes of worshipers. The temple gained people's faith and was more popularly called 'Enoshima Benten' rather than Yoganji. Enoshima remained for a long time a sacred spot where only those of upper classes were allowed to visit, and off-limits to commoners. In 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (1542-1616), the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate, visited Enoshima Benten and made it an official prayer hall for the Tokugawa family. His visit spurred faith [among commoners] in Benten. In the mid-Edo Period (1603-1868), this temple-shrine complex was finally made open to the public. Only 50 kilometers distant from Tokyo, Enoshima turned into one of the most popular and crowded religious places during the latter half of the Edo Period. Obviously, Buddhist elements such as the Benten statue were far more pronounced than Shinto deities, and Enoshima Jinja was apparently overshadowed. In fact, the entire complex was controlled by the temple called Iwamoto-in 岩本院 (now existing as an inn)......Before the Meiji Imperial Restoration of 1868, the complex abounded in Buddhism-related structures. It had a Nio-mon Gate, Three-story Pagoda, Enma-do Hall, Founding Priest's Hall, Goma (homa in Skt.) Hall, and Kannon Hall. The new government after the restoration named Shinto the official state religion. Enoshima Jinja and Shinto elements on the islet suddenly came into the spotlight. Enoshima must have undergone quite a change. Following the 'Abolish the Buddha, Destroy Sakyamuni' (Haibutsu Kishaku 廃仏稀釈) policy initiated by the government, most of the Buddhism structures were removed or scrapped shortly afterwards. The Benten statues were nearly thrown away. The new Constitution enforced in 1947 after World War II guaranteed freedom of religion, whereby Buddha statues such as Benten were restored. They retain, however, nothing of the glory of former days. Only the name 'Enoshima Benten' is better known than Enoshima Jinja."

Child-Eating Dragon of Enoshima Island. Says Indian scholar Saroj Kumar Chaudhuri in Hindu Gods and Goddesses in Japan, page 47: "The illustrated story on the origin of Enoshima Shrine, Enoshima Engi Emaki 江の島縁起絵巻, was written towards the end of the Muromachi period [circa 16th century]. It is said to be based on a story written by the monk Kōkei.......The illustrated story begins with the Japanese myth of creation of the world. Next, it continues that a five-headed dragon came and settled down near a village [Koshigoe 腰越] and started troubling villagers by eating their children. Suddenly one day in the year 552 CE, dark clouds gathered over the sea near the village, and presently an island appeared from the sea. This is the island of Enoshima. Sarasvatī descended on this island from Heaven and settled down. One day the evil dragon saw beautiful Sarasvatī and immediately fell in love with her. The dragon requested her to fulfill his desire. She agreed, provided that he gave up his evil deeds and accepted the teachings of the Buddha. He promised and his desire was fulfilled. The dragon then turned into a hill. In 699, the famous ascetic Enno Gyōja saw a vision of Sarasvatī with eight hands in a cave on the island. The monk Dōchi read the Ho-ke-kyo sutra [Lotus Sutra] from 728 to 734. Sarasvatī appeared every night to hear the sutra and gave food to the monk. The monk Kūkai saw her in a vision in 814, and made an idol of her. This was followed by visions by monks up to the year 1202. Sōzan Chomonojū 相山著聞集 written towards the end of the Edo period relates a similar story. A worshipper fell in love with the Sarasvatī idol of Enoshima Shrine and remained there for a number of days. Sarasvatī fulfilled his wish." <end quote> NOTE. This doesn't mean she had sex with the dragon. Her imagery as seductress is a didactic tool to help people overcome their sexual lust and break free of sexual desire. The link between Benzaiten and the dragon is not surprising. As this web page makes clear, Benzaiten's main avatar/companion is a snake -- and dragons are classified as a type of serpent (known in Sanskrit as Naga). Both snakes and dragons are creatures of the water and guardians of treasure, both befitting Benzaiten's role as goddess of water and wealth.

VOTIVE TABLETS FROM MODERN ENOSHIMA

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

- Votive Tablet from Enoshima Island. Modern. Shows dragon holding wish-granting jewel.

- Votive Tablet from Enoshima Island. Modern. Benten riding dragon atop clouds; two attendants; holds sword/jewel.

- Votive Tablet from Enoshima Island. Modern. Shows the Seven Lucky Gods on their "dragon" treasure ship.

- Votive Tablet from Enoshima Island. Modern. Shows Benzaiten playing biwa, with dragon in the background.

|

LEARN MORE ABOUT ENOSHIMA

|

|

Itsukushima Shrine 厳島神社 (aka Miyajima Shrine 宮島神社)

A UNESCO World Hertage Site. Isukushima-hime = Benzaiten

Address: Shimohera 1-11-1, Hatsukaichi City, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan 738-8501

Official Site: miyajima-wch.jp/jp/itsukushima/ (J-site), English Site, TEL: 0829-30-9141

English: Shinto Encyclopedia || UNESCO || Japan Nat' Tourism Org. || Wikitravel || Yomiuri

|

One of the Three Great Benten Sanctuaries (Nihon Sandai Benten 日本三大弁天) in Edo-era Japan and in modern times, as well as one of six Benzaiten strongholds reported in the early 14th-century Japanese text Keiran Shūyōshū. It was initally dedicated to the resident kami Itsukushima, venerated early on (7th-8th century) as a protector of fishermen and boats, sometime thereafter as a warrior goddess, and later still (12th century) as a manifestation of Benzaiten. The early veneration of Itsukushima's island kami probably drew inspiration from the nearby Munakata Taisha Grand Shrine (Fukuoka Prefecture), which worships the three Munakata island-water goddesses. The most important of these three, Ichikishima-hime, is commonly considered a manifestation of Benzaiten. By the late Heian era (12th century), Itsukushima's kami was known as Itsukushima Myōjin 厳島明神 and was considered a form of Benzaiten. The island sanctuary became the tutelary shrine of the Taira clan, which controlled that part of Japan. Taira no Kiyomori 平清盛 (1118-1181), whose family controlled Japan for less than two decades before being defeated by Minamoto no Yoritomo 源頼朝 (1147-1199), prayed to Itsukushima Myōjin 厳島明神 to assist him in his struggle to seize imperial authority. He also prayed to Dakiniten (another deity, as shown earlier, closely associated with Benzaiten).

Located near the southern island of Kyushu, at the foot of Mt. Misen 弥山 (530 meters), Itsukushima Shrine was awarded UNESCO World Heritage status in 1996. Among foreigners, it is widely known for its famous red torii 鳥居 (Shintō gate) standing in the sea. The shrine is old. In 811 CE, Itsukushima Shrine (popularly known as Miyajima Jinja) was presented offerings as myōjin 明神 and simultaneously listed as an imperial shrine (kansha 官社). <source: Encyclopedia of Shinto>. Itsukushima also appeared in the Engishiki 延喜式 (circa 927 CE), a 50-scroll Japanese compendium of the regulations and procedures of aristocratic government during those days. It was a first-ranked shrine in the old province of Aki 安芸 (present-day Hiroshima; formerly known as Geishū Province 芸州 or 藝州). It was also an officially designated Kyū Kanpei Chūsha 旧官幣中社 (middle-ranked nationally significant shrine that received offerings from the Imperial Court up until 1945). The shrine is home to numerous Important Cultural Properties and National Treasures, including the Heike Nōkyō 平家納経 (a lavishly ornamented copy of the Lotus Sutra produced by the Taira clan and donated to Itsukushima shrine in 1164 CE), and a Batō 抜頭 mask of a red-faced man worn in performances of Bugaku 舞楽 (imperial court dance) made by the Buddhist sculptor Shamon Gyōmyō 沙門行明 (active 12th century). With the forced separation of Buddhism and Shintōism (Shinbutsu Bunri 神仏分離) in the early Meiji period (1868-1912), Itsukushima elected to join the Shintō camp and was therefore obliged to purge itself of Buddhist influences, which included its Benzaiten icons. Let us note, however, that Itsukushima Myōjin (aka Itsukushima Hime) had many centuries earlier been identified as a kami manifestation of Benzaiten, and hence served as a stand-in for Benzaiten.

Itsukushima Shrine is today, as it was in the past, dedicated to the Three Munakata Goddesses, whose mother shrines are in nearby Fukuoka Prefecture (some 8,500 Munakata shrines nationwide). Itsukushima Shrine is also dedicated to Susano-o no Mikoto, brother of the great sun goddess Amaterasu (tutelary deity of the Imperial household). Amaterasu, as already discussed, is closely associated with Benzaiten, and the three Munakata kami were all formed when Amaterasu broke Susanō's sword, chewed it in her mouth, then blew out a mist that produced the trio <see story>.

There are numerous legends association with the shrine. Curiously, says scholar Chaudhuri (p. 38, p. 47) in Hindu Gods and Goddesses in Japan: "The Itsukushima Engi 厳島縁起 [13th-century Japanese text about the origin of Itsukushima Shrine] fails to mention the name Sarasvatī even once. Instead, the story begins with the main character falling in love with a picture of Kichijōten (Skt. = Lakṣmī) drawn on a fan (his family heirloom). The shrine has a sanctuary dedicated to Benzaiten but nothing whatsoever for worship of Kichijōten. The 1447 Gaun Nikkenroku Batsuyū 臥雲日件録 suggests the possibility that both Lakṣmī and Sarasvatī are enshrined at Itsukushima. According to one legend, a beautiful lady came to the island by boat in the reign of Empress Suiko 推古天皇 (554-628). The lady said she had been wandering on the sea. This place was very solemn and majestic. So she would settle here. She next turned into a big snake. This serpentine form suggests that the lady may be Sarasvatī. However, in the next breath, the same entry says that, according to popular legend, the deity of Itsukushima has two husbands, one old and another new. The new husband is Vaiśravaṇa (aka Bishamonten). In Japanese works, however, it is Lakṣmī, and not Sarasvatī, who is occasionally mentioned as the consort of Vaiśravaṇa." <end quote Chaudhuri>

Says Minobe Shigekatsu, The World View of Genpei Jōsuiki: "The deity of Itsukushima Shrine was also said to be the daughter of the sea dragon king, and somewhere along the line belief in her became merged with belief in the Buddhist deity Benzaiten, with the two being worshiped as one. Kiyomori revived this shrine in the mid-12th century and popularized the diety. In his youth, Kiyomori also worshiped Dakiniten to insure his own personal glory, and the story of Kiyomori's worship of Dakiniten is linked, among other things, to his belief in the Itsukushima Benzaiten. <end quote> In related matters, Monstropedia.org says: "Itsukushima Shrine is the abode of the sea-god Ryūjin's daughter. According to the Gukanshō and The Tale of Heike (Heinrich 1997:74-75), the sea-dragon empowered Emperor Antoku to ascend the throne because his father Taira no Kiyomori offered prayers at Itsukushima and declared it his ancestral shrine. When Antoku drowned himself after being defeated in the 1185 Battle of Dan-no-ura, he lost the imperial Kusanagi sword (which legendarily came from the tail of the Yamata no Orochi dragon) back into the sea. In another version, divers found the sword, which is currently housed at Atsuta Shrine. The great earthquake of 1185 was attributed to vengeful Heike spirits, specifically the dragon powers of Antoku." <end quote> NOTE: The dragon king's daughter is described in the Heike Monogatari and other medieval texts as the third daughter of the dragon king Sāgara 娑竭羅; in the Kegon-kyō 華厳経 (Flower Garland Sutra, first translated in 420 AD), Sagara is described as the dragon who causes rain to fall).

Says the Encyclopedia of Shinto: "Due to belief in the Three Female Kami of Munakata at Itsukushima Jinja, the Itsukushima kami was worshipped as a protector of fishermen and boats. Itsukushima is also known as a 'military kami' (gunshin), as seen in this passage from the Ryōjin Hishō 梁塵秘抄 [a late 12th-century Japanese text compiled by the cloistered Emperor Goshirakawa]: "To the west of the [Ōsaka] checkpoint (seki) is the kami of the battlefield, Ichibon Chūsan (Kibitsu Shrine) and Itsukushima in Aki 安芸." After becoming governor of Aki (Aki no Kami) in 1146, Taira no Kiyomori (1118-1181) often visited the shrine. Upon Kiyomori's recommendation, Goshirakawa-in and Kenshunmon-in visited the shrine in the third month of 1174, and Takakura Jōkō visited twice. At the end of the Heian Period Itsukushima was worshipped by the entire Heike clan, and in 1168 the shrine's shaden structure was restored and expanded. This connection to the Heike clan may have originated in the trade and shipping in the Inland Sea that had flourished since the days of Taira no Tadamori (Kiyomori's father). Due to Heike devotion, the Heike Nōkyō scrolls (a National Treasure) were originally donated to the shrine in 1164. In the medieval period Itsukushima was supported by the Ōuchi and Mōri clans, and the Shingon temple Suishōji became the shrine's administrative temple. Also a legend began that Kūkai founded (kaisan) the temple Misen. The "original Buddhist deity" (honji) of Itsukushima was believed to be the Eleven-faced Kannon (Ekadasamukha Avalokitesvara) or Mahâvairocana. Among commoners, a cult of Ebisu-gami developed, and Itsukushima was also worshipped by fishermen and merchants." <end quote>

Learn More About Itsukushima

|

|

Kamakura -- Hata Age Benzaiten Shrine 旗揚弁財天

located on the grounds of Tsurugaoka Hachimangū 鶴岡八幡宮

Address: 1-31, Yukinoshita 2-chome, Kamakura, Kanagawa, Japan 248-8588

Official Site: hachimangu.or.jp (J-site), TEL: 0467-22-0315

English = Kamakura Guide by Kondo T. | Kamakura Citizens Net | Kamakura City Official Site

|

|

Hata-Age Benzaiten is a sub-shrine inside the grounds of Tsurugaoka Hachimangū in Kamakura. The latter was first build around 1180 CE by famed warrior Minamoto Yoritomo 源頼朝 (1147-1199), the founder of the Kamakura shogunate. When exactly Benzaiten was introduced to Tsurugaoka Hachimangū is unclear, but in 1266 CE a shrine musician named Nakahara Mitsu-uji 中原光氏 donated a statue of a naked Benzaiten, which was initially installed in the Bugaku-in 舞楽院 (no longer extant), a center for the performance of shrine dances. <source: The Arts of Japan, Ancient and Medieval, by Seiroku Noma, p. 282> This now-famous statue is today housed at the nearby Kamakura Kokuhōkan Museum 鎌倉国宝館. With the government's forced separation of Japan's Buddha-Kami matrix in last half of the 19th century, the Tsurugaoka Hachimangū shrine-temple multiplex elected to join the Shintō camp, and Benzaiten's sub-shrine was removed because she was not considered a genuine Shintō deity. The shrine we see today was rebuilt in 1956 and named Hata Age Benzaiten. HATA AGE 旗揚 literally means "raising the banner," and indeed, this small modern Benzaiten shrine commemorates Yoritomo's raising of the clan's white banner when it declared war on the Heike-Taira clan. If we recall, Benzaiten was petitioned by both the Minamoto and Taira clans to bring them victory during decades of bloody civil war. HATA AGE can also mean "the start of a new endeavor." Thus the name heralds the "reintroduction" of Benzaiten to Tsurugaoka Hachimangū. A few words about Tsurugaoka Hachimangū seem appropriate here. Minamoto Yoritomo began construction of this shrine around 1180 CE to petition Hachiman (kami of war; tutelary of the Minamoto clan) for victory over the rival Taira 平氏 clan. In 1182, Yoritomo's wife Hōjō Masako 北条政子 (1157-1225) ordered the creation of two ponds -- a large one on the right called Genji Pond 源平池 in honor of the Minamoto clan, and a smaller one on the left called Heike Pond 平氏池 to symbolize the hated Taira clan. The Genji pond has three islands representing prosperity (three 三 is pronounced "san;" its homonym 産 means growth and productivity). The Heike Pond has four islands (four 四 is read "shi;" its homonym 死 means death and destruction). The Hata-age Benzaiten shrine is located on one island in the Genji Pond, and along its approach over a bridge are many white banners (flags). White is the color of the Minamoto clan. In bygone days, only white lotuses grew in the Genji Pond and only red lotuses grew in the Taira Pond (red was the color of the Taira clan). Today, however, lotus flowers of both colors grow in either pond, suggesting a posthumous reconciliation between the two warring clans. The annual festival of the Hata-Age Benzaiten Shrine is held on the first serpent (snake) day in the month of April in the lunar calendar -- most befitting, as Benzaiten's Ennichi 縁日 (Holy Day) falls on days of the snake. The shrine also features two large stones known as Masako Ishi 政子石. Says the Kamakura Citizens Net: "If you go around to the back of the shrine, you will come to two large rocks named after Masako, the wife of Yoritomo, the first shogun. The rocks have become symbols of a happily married couple." <end quote> Hata-Age Benzaiten Shrine is also one of the seven sites in the Kamakura Pilgrimage to the Seven Gods of Good Fortune.

|

|

Kamakura -- Zeniarai Benzaiten Ugafuku Jinja 銭洗弁財天宇賀福神社

The Money-Washing Shrine, more popularly known as Zeniarai Benten 銭洗弁天

Address: 25-16, Sasuke 2-chome, Kamakura, Kanagawa, Japan 248-0017 | TEL: 0467-25-1081

English = Kamakura Guide by Kondo T. | Kamakura Citizens Net | Kamakura City Official Site

|

Kamakura's second most-visited shrine (after Tsurugaoka Hachimangū). People believe that washing their coins and paper money in water from the shrine's sacred mountain stream will bring them financial success by "making their money multiple." According to shrine's own legends (which do not appear in period texts), the founder of the Kamakura Shōgunate -- Minamoto Yoritomo 源頼朝 (1147-1199) -- had a dream in 1185 CE on the day of the snake in the month of the snake in the year of the snake (a very auspicious day in the Zodiacal calendar). Based on the dream (see below), he ordered the construction of a shrine dedicated to Ugafukujin宇賀福神, a snake kami of water, food, and wealth. Uga 宇賀 denotes food/grain and fuku 福 means wealth. Ugafukujin is more commonly known as Ugajin, a snake-bodied human-headed kami who was merged with Benzaiten sometime in the 12th-13th century to create the combinatory fortune-bringing deity Uga Benzaiten. Today the shrine is especially popular on days of the snake, when the money-expanding wealth-expanding powers attributed to Ugafukujin are said to be most effective. We may also note that Benzaiten's Ennichi 縁日 (Holy Days) are also on days of the snake, which occur once every 60 days in odd-numbered months in the lunar calendar. Nonetheless, not all snake days are auspicious. Some days, like the snake day of the twelve month in the old lunar calendar, are considered unlucky. On this particular day, people are advised not to work the fields or get married. Such bad-luck days, and there are many, are called Kannichi 坎日. Good luck days are called Kichijitsu 吉日, but there are many different terms for days of good or bad fortune. For more on this topic, see this E-site or this E-site.

Yoritomo's Dream of Ugafukujin. Says Kamakura Citizens Net: "Minamoto no Yoritomo, the first Shōgun of the Kamakura government, prayed daily and nightly for peace and order in the country. One day, on a day of the snake in the year of the snake, an old man appeared to Yoritomo in a dream. He said, 'Your concern for the people and sincerity have impressed me greatly. Behold, I will show you a secret that will bring peace and prosperity to your country. To the northwest lies a valley where pure water runs from among the rocks. It is a holy spring. Make an offering of its water to the deities whenever you pray.' The old man disappeared, saying 'I am Ugafukujin, god of this secret hamlet.' Upon awakening, Yoritomo immediately sent his men to find the spring that had been revealed to him. When the party eventually located the spot, Yoritomo ordered a cave dug and a shrine built, which he then dedicated to Ugafukujin. Further Yoritomo ordered his men to carry water from the spring to his residence and offer it to the deities. The realm, it is said, soon knew peace, wrongdoings disappeared, and people enjoyed their lives." <end quote> NOTE: The spring that was discovered was called Kakuresato 隠里 (lit. = Hidden Hamlet) and became known as one of the five sources of pure water in Kamakura.

Says the Kamakura Guide by Kondo Takahiro: "Praying to the god Ugafuku for a bumper crop, farmers near here washed rice seeds with this spring water. Later, Ugafuku began to be worshiped as the God of Wealth and was assimilated with Benzaiten (Sarasvati in Sanskrit), the Goddess of Fortune. Sarasvati is a divinized river in Brahmanism and revered as the Goddess of Water. The shrine, therefore, demonstrates a syncretism in Japanese religions combining a Shinto god with a Buddhism deity through the common element of water. The torii gates and the incense burner indicate a reconciliation of Shinto and Buddhism elements. The object of worship enshrined here is the statue of a serpent with a human head made of stone (andesite) brought from the Izu Peninsula. A serpent is supposed to be sacred to Benzaiten. However, it is not viewable to visitors as it is enshrined deep inside a cave." Continues Kondo (author of Kamakura Guide, he is a retired business man living in nearby Yokohama): "Foreign visitors probably feel curious about the eggs sold at the souvenir shops inside the shrine,,,,,,,the favorite food of the serpent are eggs. Dedicating the eggs to the deity, they pray their wishes be answered." <end quote> Each year, the shrine holds its Benten Festival on the first serpent day of Feb. (lunar calendar).

Other locations in Kamakura also worship Ugajin. One such place is Kaizōji Temple 海蔵寺, which venerates a statue of Ugajin (see photo at right). Says Kondo T: "There are four yagura caves to the left of the main hall. One of them, the second from the back, has a red torii gate, a symbol of Shinto shrines. Behind the torii is a stone statue of Ugajin. Though the head part is badly worn, it shows a snake coiled up around the body. Ugajin is the god of food, one of the Shinto pantheon, but was merged with Benten (Sarasvati in Skt.) in Japan. Zeniarai Benten is a shrine sacred to Ugajin." <end quote>

Benzaiten's money-washing tradition is easy to understand. She is the water goddess of wealth and good fortune, and shrines/temples devoted to her are nearly always located near water (river, pond, lake, ocean). She is associated with the Naga (serpents and dragons), who guard treasure. But there is another deity, known as Fudō Myō-ō, who can work the same miracle. But why Fudō Myō-ō? His real symbol is fire. His aureole is almost always the flames of fire. He is also the main honzon for GOMA 護摩, a fire ceremony still popular today in which defilements are symbolically burnt away. So why would people wash money under Fudō's protection? Because he washes away impurities? Maybe, perhaps, because drawings of Fudō show him standing on a rock rising from the sea. For example, the drawing at Daigoji 醍醐寺, Kyoto, and the famous 1282 drawing by Shinkai 信海 of Fudō standing on a rock rising from the sea. Moreover, the Kurikara (an icon of the dragon wound around a sword) often appears in Fudō paintings. Also, both the Kurikara & Fudō are found often near ascetic practice places, such as small waterfalls. Perhaps this is the reason. For more details, see Gabi Greve's Fudō Money-Washing.

|

|

Tenkawa Grand Benzaiten Shrine

Tenkawa Jinja 天河神社, aka Tenkawa Daibenzaitensha 天河大弁財天社

Address: Tsubonōchi, Tenkawa, Yoshino District, Nara Prefecture, Japan 638-0321

Official Site: tenkawa-jinja.or.jp (J-site), TEL: 0747-63-0558

|

One of the Five Great Benten Sanctuaries (Nihon Godai Benzaiten 日本五大辯財天) in modern Japan, as well as one of Benzaiten's "Six Pure Lands" as reported in the early 14th-century Japanese text Keiran Shūyōshū 渓嵐拾葉集. Geographically situated inside a triangle whose three corners are the sacred mountain centers of "divine energy" -- Kōya 高野, Yoshino 吉野, and Kumano 熊野 -- shrine authorities say Tenkawa Jinja can trace its origins back to antiquity, to the hagiographies of Emperor Jimmu 神武天皇 (Japan's mythical first emperor), to Shugendō founder En no Gyōja (late 7th century CE), and to Shingon founder Kūkai (774-835 CE; aka Kōbō Daishi). The shrine also claims to possess the sacred Isuzu 五十鈴 (lit. 50 bells), a triangle formed by three circular bells containing 50 kami. This devise, the shrine insists, was held by goddess Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto 天宇受売命 during her erotic and humorous dance that coaxed Amaterasu to come out from her cave to bring light back into the world. Tenkawa Shrine venerates numerous deities, including a fantastic esoteric three-headed-snake form of Benzaiten known as Tenkawa Benzaiten and a more common 8-armed martial form called Uga Benzaiten. According to the Tamon-in Nikki 多門院日記 (Diary of Tamon-in), a Japanese text written by Eishun 英俊 (1518-1596) and other monks of Kōfukuji Temple (Nara) during the latter half of the Muromachi era (1392-1573), it was Emperor Temmu 天武天皇 (reigned 672-686) who built the first imperial-sponsored shrine at Tenkawa, one dedicated to Benzaiten, who, it is said, had appeared to Shugendō founder En no Gyōja while he was praying in the Yoshino mountains. Legend contents that En no Gyōja then installed her image atop Mt. Misen 弥山 (directly behind Tenkawa Shrine; a mountain supposedly already associated with the kami of water). The shrine likewise contends that legendary Emperor Jimmu received, via divine oracle, the term Hi no Moto 日ノ本 at this sacred location. The term was eventually shortened to Nihon 日本 (meaning JAPAN). We might also mention that Jimmu's legend includes the story of a magical three-legged black crow sent by Amaterasu to aid him (after he had gotten lost). Jimmu eventually found Yamato, the heartland of Japan, thanks to the crow. Not to be forgotten, Tenkawa Jinja maintains a stage for traditional NOH theater (Nō 能) and hosts a variety of theatrical performances each year. Benzaiten, if we recall, is the goddess of performing arts, music, dance, singing, discourse, etc. According to one Japanese legend, if you want to become a professional vocalist, you must venerate Benzaiten with special esoteric hand gestures (mudra) and esoteric incantations (mantra). <source this J-site> The Keiran Shūyōshū, compiled in the 14th century, contains many of the oral legends of these times. Click here for one curious story about Tenkawa

REFERENCE:

Chaudhuri, Saroj Kumar. Hindu Gods and Goddesses in Japan. Vedams, 2003, p. 44, ISBN : 81-7936-009-1.

"Long ago, this place [Amanogawa, aka Tenkawa] was a big sea. Two dragons, one good and another bad, lived here. The bad dragon troubled people living in the neighbourhood. Two gods took pity on the people and decided to subdue the bad dragon. The [bad] dragon appeared and started emitting his poisonous breath. One of the gods took out an eight-eyed arrow and shot it into the throat of the dragon. The subdued bad dragon sank into the sea. Next, it enveloped its body in water and rose into the sky. This water became the present Amanogawa River. The good dragon, in this case, is the goddess Sarasvati. The two gods who subdued the bad dragon are her children. This is the most important Sarasvati shrine in Japan. Regarding Sarasvati of Chikubushima, it says that she is the second daughter of [Dragon] King Sagara. The Ke-gon-gyo Sutra [Sutra of Golden Light] says that there is a small country in the north-east, where there is a lake with an island in it. This island is the residence of Sarasvati. It is her holy site."

.

Learn More About Tenkawa Jinja at These Outside Sites

Old Artwork of Tenkawa | Japan Nat'l Tourism Organization | Aikido Journal | Weblio Quotes

|

|

Kinkazan Koganeyama Jinja 金華山 黄金山神社

Address: Miyagi Precture, Ishinomaki City, Ayukawahama Kinkazan 5, 〒986-2523

Web Site (J-Site) and History (J-site). TEL: 0225-45-2301. Map from iTouch.

|

One of the Five Great Benten Sanctuaries (Nihon Godai Benzaiten 日本五大辯財天) in modern Japan. Kinkazan (Kinkasan) 金華山 is an island in the Pacific Ocean near Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture. Worship at Kinkazan reportedly began in the mid-8th century CE after the discovery of gold at nearby Tōda-gun 遠田郡 (on the mainland; the nation's first gold mine). In 749, the clan lord of the region -- Kudara no Konikishi Kyōfuku 百済王敬福 (697-766) -- presented Emperor Shōmu 聖武天皇 (701-756) with a large contribution of gold for the construction of the Great Buddha icon in Nara. Ever since then, Kinkazan has been associated with gold and wealth, hence its various names: Kanayama 金山 (Gold Mountain), Koganeyama 黄金山 (Yellow Gold Mountain), or Kinkazan 金華山 (Gold Lotus Mountain). At one point in time, it was also a site for gold prospecting. Along with Dewa Sanzan 出羽三山 and Osorezan 恐山, Kinkazan is one of the three most sacred Shugendō mountain sites in Japan's Tohoku region 東奥・東北 (northeast Honshu). From the beginning, it was dedicated to two kami tutelaries of metals, mines, and mining known as Kanayama Biko no Kami 金山毘古神 (male) and Kanayama Bime no Kami 金山毘賣神 (female). According to the Kojiki, this male-female pair were born from the vomit emitted by Izanami as she lay dying following the birth of the kami of fire Kagutsuchi 迦具土神 (Kojiki)or 軻遇突智 (Nihongi). <see Encyclopedia of Shinto> Sometime in the medieval periodEra Names & Dates:

Standard dating scheme found in both Japan and the West.

- Ancient refers to the Asuka and Nara periods (538-794)

- Classical refers to the Heian period (794-1185)

- Medieval refers to the Kamakura era (1185-1333), Muromachi era (1336-1573), and Edo era (1600-1867)

- Modern refers to everything since 1868 (Meiji, Taisho, Showa, & Heisei periods)

NOTE: Ancient & Classical are sometimes used collectively to refer to everything through the Nara era. The Edo Period is also known as "Early Modern," while Meiji and after are the "Modern" period. The term "Premodern" refers to pre-Meiji. (perhaps the late 16th century), the shrine-temple multiplex at Kinkazan adopted Benzaiten (the water-island goddess of wealth) as its main icon of veneration. The Kinkazan multiplex, then known as the Koganeyama Daikinji Temple 金華山大金寺, was largely destroyed in a fire in the the late 16th century but then regained its splendor thanks to the patronage of the Date clan (伊達氏), a line of daimyō 大名 who ruled the Tōhoku region from the late 16th century into the Edo era. In the early Meiji period, during the forced separation of Buddhism and Shintōism, Kinkazan elected to join the Shintō camp and changed its main tutelaries to Ōwadatsumi-no-Kami 大綿津見神 (Great-Ocean-Possessing Kami) and Ichikishimahime (a popular Shintō manifestation of Benzaiten), while also retaining its veneration of the male-female Kanayama kami pair. These associations reflect Benzaiten's continuing importance to the complex (after all, Benzaiten is a goddess of water, islands, and wealth). Other deities worshipped today at Kinkazan include Ebisu (kami of the ocean and fishing folk) and Daikokuten (Hindu-Buddhist deity of agriculture in Japan). Ebisu and Daikokuten are also members of Japan's Seven Lucky Gods. Within the Kinkazan compound, visitors can wash their money at a Zeniarai Benten (Money-Washing) shrine -- this is meant to make their money multiply and expand, i.e., to bring them good financial gains. Local lore says those who visit the shrine three years in a row will become rich. The shrine also holds ceremonies six times yearly on snake days (Benzaiten's Ennichi 縁日, or holy days, which occur every 60 days in odd-numbered months). It also hosts an annual Ryūjinsai 龍神祭 (Dragon Festival) in July. An eight-armed Benzaiten is enshrined in a special hall dedicated to Benzaiten, and a special stone monument to the Eight Great Dragon Kings adorns its outdoor pathways. SPECULATION. What prompted Kinkazan to adopt Benzaiten as its tutelary deity? The most probable theories involve wordplay, wealth, and water. Kinkazan 金華山 (Gold Lotus Mountain) is written with the character KIN 金, meaning gold or metal. If we recall, Benzaiten is introduced in the Sutra of Golden Light 金光明經. Since Benzaiten became a goddess of wealth after her merger with the wealth-bringing snake kami Ugajin, her linkage with earthly treasures (gold) is most appropriate. She is also a water-island goddess, one closely associated with the NAGA (serpents and dragons) who guard treasure and rule the waters. Gold and earthly treasure also lead us to Bishamonten (lord of treasure, dispenser of riches). He appears often in Benzaiten artwork, and along with her, is one of Japan's Seven Gods of Good Fortune. His messenger, the centipede, is credited with the ability to sniff out gold mines in mountain deposits.

|

|

Seven Benten of Mt. Kōya ・ Kōya Shichi Benten 高野七弁天

Address: Wakayama Pref., Ito-gun, Kōya-machi, Kōyasan 306 TEL: 0736-56-2029

Official English Site koyasan.or.jp/english, J-site koyasan.or.jp or Museum Reihōkan Koyasan

Kōyasan 高野山 in Wakayama Prefecture is the headquarters of Japan's esoteric Shingon sect, and the head temple is Kongōbu-ji 金剛峯寺. The temple's name means "Temple of the Diamond Mountain." Kōyasan is part of the "Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes in the Kii Mountain Range." It is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site.

|

The Seven Benten of Mt. Kōya 高野山・七弁財天 remain a mystery to me. This entry is preliminary and may include errors. It is offered here as a convenience to those interested in Benten's influence and geographical distribution in medieval (PN)Era Names & Dates (Popup Note):

Standard dating scheme found in both Japan and the West.

- Ancient refers to the Asuka and Nara periods (538-794)

- Classical refers to the Heian period (794-1185)

- Medieval refers to the Kamakura era (1185-1333), Muromachi era (1336-1573), and Edo era (1600-1867)

- Modern refers to everything since 1868 (Meiji, Taisho, Showa, & Heisei periods)

NOTE: Ancient & Classical are sometimes used collectively to refer to everything through the Nara era. The Edo Period is also known as "Early Modern," while Meiji and after are the "Modern" period. The term "Premodern" refers to pre-Meiji. and modern Japan. Mt. Kōya is the headquarters of Japan's esoteric Shingon sect, founded in the early 9th century by Kūkai 空海 (774 - 835 CE), who is known posthumously as Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師. Based on the legends of this powerful temple-shrine multiplex, Benzaiten faith at Mt. Kōya began with Kūkai, who by tradition payed homage to the deity atop Mt. Benten-dake 弁天岳 (984.5 meters). Mount Benten constitutes the western edge of the Kōya compound. At its base is the Great Gate (Daimon 大門), where pilgrims typically started their religious journey into the sprawling compound. More importantly, Mt. Benten is revered as a sacred water source for the mountain complex. The headwaters of the Odogawa 御殿川 river flow from Mt. Benten in an easterly direction (tōryū 東流, lit. eastern flow), prompting Kūkai to declare the area the lair of the dragon (see citation below). If we recall, the dragon is the messenger and avatar of Benzaiten. Dragons are also considered lords of the water and guardians of the east. Tōryū 東流 may also be written 東龍 (the latter means "East Dragon"). The effigies of Benzaiten venerated at the seven Kōya sites are all dated to the 17th century or earlier. Most are icons of Uga Benzaiten (see chart below). All seven sites are considered sacred sources of water. <need to confirm this> Again, according to unconfirmed temple legends, Kūkai is credited with inviting-invoking the nearby deity of Tenkawa Jinja (a form of Uga Benzaiten) to take up residence at Dakeno Bentensha 嶽弁財天社 on Mt. Kōya. The Reihōkan Museum 霊宝館 at Mt. Kōya (home to thousands of Shingon treasures) says this helps explain why the Seven Kōya Benten are largely devoted to the same deity. Nonetheless, Uga Benzaiten does not appear in Japanese art and literature until well after Kūkai, so we must dismiss such legends. CITATION. The Henjō Hokkishōryōshū 遍照発揮性霊集, a 10-handscroll work of the 9th-century (circa 835) said to contain poems and quotations by Shingon founder Kūkai as collected and edited by his disciple Shinzei 真済 (800-860 CE). Handscrolls eight, nine, and ten were lost, but reappeared in the 11th-century (circa 1079) as part of the apocryphal expanded version of Kūkai's sayings compiled by Shingon monk Saisen 済暹 (1025-1115), which was known as the Zoku Henjō Hokkishōryōshū Hoketsushō 続遍照発揮性霊集補闕鈔. Handscroll nine of the latter work includes a section entitled Kōyasan Shiji Kei Byaku Mon 高野山四至敬白文, in which Kukai reportedly described the area as the "lair of the dragon."

|

Name

|

Number of Arms

|

Main Object of Worship

|

|

Dakeno Bentensha 嶽弁財天社

|

Uninvestigated

|

Ugajin (Male)

|

|

Haraikawa Bentensha 祓川弁財天社

|

Eight

|

Uga Benzaiten & 15 Disciples

|

|

Yuyadani Bentensha 湯屋谷弁財天社

|

Eight

|

Uga Benzaiten & 15 Disciples

|

|

Funahiki Bentensha 綱引(船引)弁財天社

|

--

|

Ugajin (Female)

|

|

Kadode Bentensha 首途(門出)弁財天社

|

Uninvestigated

|

Hidden Buddha (not revealed)

|

|

Osaki Bentensha 尾先弁財天社

Kensaki Bentensha 剣先弁財天社

|

Uninvestigated

Two

|

Univestigated

Benzaiten

|

|

Maruyama Bentensha 丸山弁財天社

|

Two

|

Uga Benzaiten

|

|

Source: Museum Reihōkan Koyasan, translation by M. Schumacher. Located in the compound, Reihōkan Museum stores thousands of treasures from Mt. Kōya. Learn more about Kōya's Benten: J-site 1 | J-site 2 | J-site 3 | J-site 4

|

|

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

click to enlarge

|

- Benzaiten Playing Biwa atop a rock surrounded by the sea. Scroll, colors on silk, H = 104 cm, W = 39 cm, 14th Century, Kōyasan Hōjyōin Temple 高野山宝城院. <Photo: Treasures of a Sacred Mountain. Kūkai and Mt. Kōya. 1200-Year Anniversary of Kūkai's Visit to Tang-Dynasty China. Tokyo Nat'l Museum catalog, 2004.

- Benzaiten and 15 Disciples. Jimyō-in 持明院, Mt. Kōya. <Photo Source>

- Ofuda talisman showing unconventional two-armed Benzaiten holding wish-granting jewel and a drum-like object in her hands. Sword slung over her back. The drum-like object looks (to me) like Daikokuten's good-luck hammer (uchide nokozuchi 打ち出の小槌). From Renge-in 蓮花院, Mt. Kōya. <Photo Source>

- Ugajin, Male, Kōyasan Shinnōin Temple, 高野山親王院. <Photo Source>

- Ugajin, Female, Kōyasan Shinnōin Temple, 高野山親王院. <Photo Source>

|

|

|

|

|

Shugendō Sanctuaries - Mt. Haguro & Dewa Sanzan

|

|

|

|

Cutout of scroll painting; post-Meiji era. The kami of Mt. Haguro appears as a feminine deity. She might be Tamayorihime 玉依比売

(the divine bride), who is also identified with Ideha-no-Kami 伊弖波神. The latter is considered the original deity of Mt. Haguro, but today the mountain's main kami is Ukanomitama, more commonly known as Inari, the kami of rice. As this page has shown, Benzaiten and Inari are closely linked in Japan's combinatory Buddha-Kami matrix. Photo Gaynor Sekimori

|

|

The Three Mountains of Dewa Sanzan 出羽三山 are one of Japan's most important Shugendō 修験道 enclaves of mountain asceticism. Running from north to south in Yamagata Prefecture, the three are Mt. Haguro 羽黒山, Mt. Gassan 月山 and Mt. Yudono 湯殿山. Below text quoted from the 2005 film Shugen: The Autumn Peak of Haguro Shugendō: "The Sanjin Gosaiden 三神合祭殿 of Dewa Sanzan Shrine was formerly the Main Hall of the Buddhist temple Jakkōji Temple 寂光寺. The most sacred object of veneration here is a rock called Goshinpi 御神秘, secreted below the floor of the shrine. In front of the shrine is a sacred pond called Mitarashi 御手洗 [where worshippers wash their hands and mouths before venerating the deity]. More than 600 small votive bronze mirrors, dating from the 12th to the 18th century have been found here. Beside the pond is a shrine dedicated to Benzaiten, the goddess of eloquence, art, wealth and longevity. This deity is depicted with a kami of good fortune, called Ugajin, on its head. Ugajin has the face of an old man and the body of a snake." <end quote; translation by Gaynor Sekimori>

Since the forced separation of Shintō and Buddhism by the Meiji government in 1868, the main kami of Mt. Haguro became Uganomitama-no-Mikoto 宇迦之御魂神, the kami of foodstuffs, who is more popularly known as Inari (the Japanese kami of rice and the spirit of rice). There are over 32,000 Inari shrines in Japan today, the largest number for any single kami. <source: Jinja Shinpō 神社新報社刊, Vol. 2772, Jan. 17, 2005> Uganomitama is also identified with Ugajin and with Tamayorihime 玉依比売 (the divine bride and fertility goddess). The original kami of Mt Haguro seems to have been Ideha-no-Kami 伊弖波神, the tutelary deity of the old province of Ideha (Haguro), who is sometimes identified as Tamayorihime. Nonetheless, the most general kami identification for Mt. Haguro in modern times is Ukanomitama.

This is an important point. As this paper has shown, Benzaiten and Inari and the white-snake kami known as Ugajin are intimately intertwined as deities of the rice crop, agricultural, water, rain, and the prosperity of the people. The image of the kami of Mt. Haguro at right, interestingly, incorporates many of Benzaiten's key attributes -- female, standing on a rock surrounded by waves (she is an island goddess after all), holding a wish-granting jewel in one hand (one of her main attributes) and bountiful rice stalks in the other. Another point of interest is the mention of 600 small votive bronze mirrors found near her shrine at Mt. Haguro and the mention of a sacred rock. Mirrors are one the the three regalia of Shintō, especially related to the supreme sun goddess Amaterasu, who was coaxed out of seclusion in her heavenly rock cave by her own brilliant reflection in a mirror, whence she brought light back into the world. As we have discovered, Benzaiten and Amaterasu are different manifestations of the same deity.

|

|

Shugendō Sanctuaries - Sefurizan 背振山 or 脊振山

Benzaiten = Otogohō Zenshin and Nāgārjuna

Official Name: Sefurizan Sekisui Kyōji Shugakuin 背振山積翠教寺修学院

ADDRESS: Saga Pref., Kanzaki Gun, Yoshinogari Machi, 1400 Banchi

Official Site: sefurizan.com (J-site), TEL: 0952-52-5285

|

|

|

|

Otogohō Zenshin 乙護法善神

or Otogohō Dōji 乙護法童子.

A manifestation of Benzaiten.

Asosan Sangandenji Temple

阿蘇山西巌殿寺 in Kumamoto. Holds vajra (Tokkosho 独鈷杵) in left hand and staff in the other. Otogohō is composed of the character Oto 乙 (meaning "last" of 15 sons) and the term Gohō 護法, meaning "Dharma protecting." Artwork of the diety is scarce. He sometimes appears as a youthful red-colored Dōji 童子 (attendant). If we recall, Benzaiten appears with a red face when depicted as the Three-Faced Deva, but this probably has no significance, as Dōji are commonly portrayed in red in Japanese artwork. Photo: Sefurizan.com. For more,

see J-site #1 or #2

|

|

|

|

|

The shrine-temple multiplex Sefurizan (aka Sefurisan, Seburiyama) was mentioned as one of six Benzaiten strongholds in the early 14th-century Japanese text Keiran Shūyōshū, although its first appearance in literature was in the late 9th-century Nihon Sandai Jitsuroku 日本三代実録. <Fukuoka City Museum> Located in the mountains bordering Saga and Fukuoka prefectures, it was an important syncretic center of religious mountain worship (Sangaku Shūkyō 山岳宗教) and Shugendō practice in old Japan. The multiplex claims strong linkages to the haliographies of famous monks like Ennin 円仁 (794-864 CE, aka Jikaku Daishi 慈覚大師), who reportedly invited the combinatory Hindu-kami Otogohō Zenshin 乙護法善神 to reside here; to Shōkū Shōnin 性空上人 (active mid 10th century CE), the alleged founder of Shugendō practice at Sefurizan; and to Tendai monk Kōkei Ajari 皇慶阿闍梨 (977-1049. <sources: J-site #1 and J-site #2> The story of Otogohō (the protective deity of these mountains; aka Otogū-san 乙宮さん or Otogohō Dōji 乙護法童子; lit. = youngest protector of the dharma) links him directly to Benzaiten and also helps to explain why Benzaiten is identified with Nāgārjuna 龍樹 (Jp. = Ryūju, Chn. = Lóngshù). Nāgārjuna lived in southern India sometime in the 2nd-3rd centuries CE. He is one of the most esteemed Buddhist teachers and philosophers in India, China, and Japan, and in many Mahāyāna traditions he is considered second only to Buddha himself. Here is the story in a nutshell as it appears in the 14th-century Keiran Shūyōshū and on the Sefurizan web site: "According to Sefuriyama Engi, a king from southern India (Jp. = Tokuzen Daiō 徳善大王) had 15 sons, but the last son mysteriously disappeared seven days after birth. The king prayed to Nāgārjuna to help him locate the missing boy. Nāgārjuna informs the king that his son is living at Sefurizan in Japan. The king is overjoyed. Together with his 14 sons and Nāgārjuna they journey to Sefurizan. The king becomes the tutelary deity (chinju 鎮守) of Sefurizan and is given the title Sefuri Gongen 背振権現. <end story; translation by Schumacher> This account accurately reflects the original story in the 14th-century Keiran Shūyōshū (see T. 76, 2410, 783c.), but the latter text goes on to say that: "The king became Sarasvatī (Benzaiten), as well as one of the Sixteen Benevolent Deities (zenshin 善神) and one of the Sixteen Great Bodhisattvas. The fifteen princes are his acolytes (dōji). The youngest prince is Sensha Dōji 船車童子 and is also known as Otogohō [the leader of the others]. He is also known as Seitaka Dōji 制吒迦童子, one of Fudō's Gohō Dōji 護法童子 (lit. "dharma protectors). Among the five hundred eighty thousand dōji 五億八千童子中 of Saishō ō kyō (Golden Light Sutra), the fifteenth dōji, Sensha Dōji, is the foremost and is also known as Kisho Myōzō Dōji 吉祥妙藏童子." <translation by Irene H. Lin, pp. 156-157, Pacific World Journal, 2004> As a group, the king and his 15 sons embody Benzaiten 總體辨財天. According to other Sefurizan legends, King Tokuzen Daiō (aka Sefuri Gongen, aka Benzaiten) flew here on a dragon (Benten's customary avatar and messenger) from the Korean Kingdom of Kudara 百済, while Otogohō flew here on a dragon from southern India. <source: this J-site> Otogohō becomes Benzaiten's adopted son and the leader of Benzaiten's 15 sons/disciples. Otogohō is also considered a mountain god who drives away pests who could harm the agricultural crop. This story also helps to explain the involvement of Nāgārjuna 龍樹, whose name literally means "Dragon Tree," which is suggestive of a pillar. The central pillars at Ise's Outer Shrine are the residence of Benzaiten. Nāgārjuna also represents the white snakes that reportedly live under the central pillars of the inner and outer shrines at Ise. <source: Teeuwen & Rambelli, pp. 49-52> This complex web of associations leads us to Amaterasu, the Supreme Kami of Japan, who can also manifest as the Hindu-Buddhist-Kami Benzaiten. Today, the Sefurizan sanctuary worships Fudo Myō-ō (Otogohō/Seitaka is, after all, one of his most important attendants) and Enmei Jizō (Life-Prolonging Jizō). The latter is worshipped here for the longterm well-being of the family, easy delivery, academic achievement, travel safety, and a host of other mundane matters. The upper shrine is devoted to Benzaiten, and the middle shrine to Otogohō. Mountain faith in Otogohō also spread to Asosan 阿蘇山 in Kyushu and to Shoshazan 書写山 in Hyōgo (known as the Western Mt. Hiei 西の比叡山, thereby linking it to the esoteric Tendai multiplex atop Mt. Hiei). For more on Otogohō, see PN note.

|

|

Tokyo Sanctuaries - Namiyoke Inari Shrine 波除稲荷神社

Near Tsukiji Fish Market. Features a Black-Toothed Benzaiten.

Address: 6-20-37 Tsukiji, Chū-ō Ward, Tokyo, Japan 104-0045

Official Site: namiyoke.or.jp (J-site), TEL: 03-3541-8451. Google Maps.

|

|

|

|

|

The shrine venerates Inari (rice kami), foxes (messengers of Inari), shishi lion protectors, and a curious black-toothed form of Benzaiten. The shrine's shishi effigies are said to be manifestations of Inari & Benzaiten. Photo Schumacher.

|

Women carrying the 700-kg black-toothed

shishi called "Benzaiten Ohaguro Shishi."

Namiyoke Inari Shrine, Tsukiji Shishi Matsuri.

Photo on display at Namiyoke Inari Shrine.

|

|

People come to this Tokyo shrine to pray for business success and safe construction (of buildings), and to gain protection against misfortune. The 350-year-old shrine holds the Tsukiji Shishi Matsuri 築地獅子祭 (Lion Festival) and parade annually in mid-June. The festival features a 700-kg black-toothed female shishi known as the Benzaiten Ohaguro Shishi 弁財天お歯黒獅子 (Benzaiten Black-Toothed Shishi) and the male Tenjō Ōjishi 天井大獅子 (Great Heavenly Shishi). These are paraded around the nearby area, but only women are allowed to carry the black-toothed female shishi, while only men can carry the male shishi. Other effigies of the lion-dog (those owned by local parishioner groups) are carried around as well. According to the shrine, construction of the shrine during the Edo period ran into difficulties due to ocean tides (the shrine is located near the sea). When construction seemed impossible, an image of Inari miraculously floated into view and construction was completed successfully. The image is reportedly housed inside the shrine. For a few more details, see this E-site.

A Note on Black Teeth. Says Gina Collia-Suzuki in Floating Along in the World of Japanese Prints: "Ohaguro お歯黒, or teeth blackening, was a common practise amongst married women, with the dye being applied for the first time just before a young bride entered her husband's home. It was also practiced within the Yoshiwara 吉原 (pleasure quarter of Edo), where a young kamuro 禿 (apprentice) who was about to come of age and accept her first customer would collect the ingredients from seven friends and dye her teeth for the first time, just as the soon-to-be bride would collect the ingredients from friends and family before her wedding." <end quote> The tradition of blackening teeth goes back to Japan's ancient periodEra Names & Dates:

Standard dating scheme found in both Japan and the West.

- Ancient refers to the Asuka and Nara periods (538-744)

- Classical refers to the Heian period (794-1184)

- Medieval refers to the Kamakura period (1185-1332) through the Edo era (1600-1868)

- Modern refers to everything since 1868

. Over time, it came to symbolize many things, such as coming of age or maturity, and served as a signal that a woman was married. The exact meaning of the black-toothed Benzaiten Shishi escapes me, but Benzaiten is said to be a jealous deity, one identified with many curious practices and taboos that, if not followed, will lead to the breaking up of loving couples or happily married people.

|

|

Tokyo Sanctuaries - Other Benzaiten Enclaves

|

|

|

Votive Tablet, Inokashira Benten Hall

井の頭弁財天本堂 Inokashira Kōen

井の頭公園, Tokyo. A stone statue of Ugajin is located near the hall. This votive tablet depicts Ugajin as a white snake. The character 寶 (treasure of buddha-nature) is drawn inside a wish-granting jewel, and the character 財 (meaning wealth) draw inside a money bag. Key to the storehouse shown at bottom. Sanskrit seed at center read U, for Ugajin. Photo this J-site. Also see Inokashira Benzaiten photos

Votive tablet at Shinobazu, Ueno, Tokyo

Depicts the Eight-Armed Happi Benzaiten

|

|

Let us quote again from scholar and translator Richard Thornhill: "Some Tokyo shrines include the temple at Shinobazu Pond 不忍池, Ueno, in central Tokyo, and at Inokashira Pond 井の頭池 at Kichijōji Temple 吉祥寺 in the western suburbs. It has a Bentendō on a small island reached by two bridges. At Shakuji-i 石神井, a couple of miles north of Kichijōji, there is Sanpō Pond 三宝寺池, with Itsukushima Jinja 厳島神社 on a small island at one end, surrounded by lotuses. The pond is one of the sources of Shakuji-i River and used to be a place of annual pilgrimage for the rice farmers living along its banks. For centuries it has been taboo to hunt or collect timber, plants or fuel in or around the pond, and it is now an outstanding nature reserve. At a fork in the road near Shinjuku, Tokyo, there is the tiny Nuke Benten 抜弁天 or Ichikishima Jinja 厳嶋神社, a tiny island surrounded by goldfish-filled ponds. Hakone Jinja 箱根神社 on Lake Ashi 芦ノ湖 is a favorite weekend destination for Tokyoites. In the grounds there is an exquisite pond full of carp, with a small Benten shrine on a mossy rock in the middle. There is no bridge, but the floor of the pond is covered with coins thrown in as offerings. At all these shrines, one can sense the continued presence of this Goddess who came from India to bless this land of the rising sun." <end quote, from Sarasvati in Japan, Hinduism Today, 2002>

For a fascinating review of the Tokyo-based Yushima Tenjin Shrine 湯島天神, which was formerly a part of a shrine-templex complex before the forced separation of Buddhism-Shintoism in the Meiji period, see The Logic of Combinatory Deities by Iyanaga Nobumi, pp. 145-176, in Buddhas and Kami in Japan. Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. The temple is now known as Shinjōin 心城院 (Tendai sect), but before the Meiji era it was named Hōju Benzaiten dō 宝珠弁財天堂 (Hall of the Wish-Fulfilling Jewel-Holding Sarasvatī) and included in the precincts of Yushima Tenjin. The complex today worships a wide range of deities, including Sugawara no Michizane 菅原道真 (845-903), Shōten 聖天 (Gaṇeśa), 11-Headed Kannon, Benzaiten, Dakini-Inari, Shusse 出世 Daikokuten (of success in life), and Jizō.

|

|

Shamoji 杓文字 (Rice Spoon) Shaped Like Benten's Biwa

|

|

Signboard, Enoshima, Modern.

In the shape of a biwa (Benzaiten's standard instrument)

and a rice scoop (shamoji 杓文字). Photo by Schumacher

|

Modern. Enoshima.

Benzaiten Playing the Flute. Painted on Rice Scoop.

|

|

The Shamoji 杓文字, or rice scooper, was reportedly first devised by a monk from the Benzaiten island sanctuary at Itsukushima Shrine (Hiroshima). This biwa-shaped wooden spoon is used to serve cooked rice everywhere in Japan. It supposedly symbolizes both Benzaiten's musical instrument (the biwa or lute) and Benzaiten's linkage to agriculture and the rice crop. Small and large versions of the shamoji are sold as popular souvenirs at many Benzaiten shrines in modern Japan. <Above photo of Shamoji (rice spoons) at Chikubushima from this J-site> Also see E-Link 1 | E-Link 2

|

|

RESOURCES, LEARN MORE

- Keiran Shūyōshū 渓嵐拾葉集, a multi-volume document compiled between 1318-1348 AD that contains many of the oral legends of the Tendai esoteric stronghold at Mt. Hiei and discusses Uga Benzaiten in detail. Also tells the tale of Ninkai 仁海 (d. 1046), the founder of the Ono branch 小野流 of Shingon Esoteric Buddhism; also tells the story of monk Ryōkanbō Ninshō 良観房忍性. This Japanese text is discussed at length by Sarah Alizah Fremerman (see below). The title of this monumental Japanese text is translated by scholar Allan G. Grapard as A Collection of Leaves Gathered from Stormy Streams. Says Fremerman: "It is in fact a vast compendium of 'leaves,' discrete fragments of esoteric knowledge transmitted orally and recorded on strips of paper, passed down from master to disciple in hundreds of distinct spiritual lineages that characterized religious tradition of medieval Tendai." <end quote, p. 150, Fremerman> Also see Allan G. Grapard, "Keiranshūyōshū: A Different Perspective on Mt. Hiei in the Medieval Period," in Richard K. Payne, ed., Revisioning "Kamakura" Buddhism (University of Hawai'i Press, 1998).

- Besson Zakki 別尊雑記, a Japanese Buddhist text compiled by Shingon monk Shinkaku 心覚 (1117-1180) and translated as "Miscellaneous Record of Classified Sacred Images." T. Zuzō 3. For scroll one, see this J-site.

- Butsuzō-zui (Butsu-zō-zu-i) 仏像図彙, or Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images, was first published in 1690 (Genroku 元禄 3), and has since become a landmark Japanese dictionary of Buddhist iconography. Hundreds of black-and-white drawings, with deities classified into categories based on function and attributes. For an extant copy from 1690, visit the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library. An expanded version, known as the Zōho Shoshū Butsuzō-zui 増補諸宗仏像図彙 (Enlarged Edition Encompassing Various Sects of the Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images), was published in 1783. View a digitized version (1796 reprint of the 1783 edition) at the Ehime University Library.

- For a larger list of resources, see references given in the main text or jump to the Benzaiten resource section.

|

|

This is a Side Page

Return to Main Benzaiten Page

|

|

|

|