|

|

|

|

SECTS & SCHOOLS OF

JAPANESE BUDDHISM & SHINTOISM

Guide to Sects, Schools, and Temples in Japan’s Religious Traditions

Still Under Construction

|

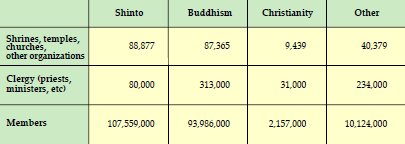

OVERVIEW: Modern Japanese Buddhism includes 13 traditional sects and nearly 100 sub-sects. Of the thirteen, three originated in the Asuka / Nara era, two in the Heian era, and virtually all the rest in the Kamakura period. The number thirteen is rather arbitrary, but follows a Buddhist tradition set earlier in China. Curiously, during Japan’s Meiji Restoration 明治維新 (late 19th century), the government officially recognized 13 Shintō sects outside its own state-sponsored shrines (the latter devoted to glorifying the emperor). This is surprising given the Meiji government’s anti-Buddhist policies. According to recent government statistics (Agency for Cultural Affairs), the number of religious groups in Japan at the end of 2003 were:

- Jōdo & Jōdo Shin = 30,000

- Zen = 21,000

- Shingon = 15,000

- Nichiren = 14,000

- Tendai = 5,000

- Shinto Shrines =88,877

- Christian Churches = 9,439

- Others (minimal)

- For newest statistics (2007), click here.

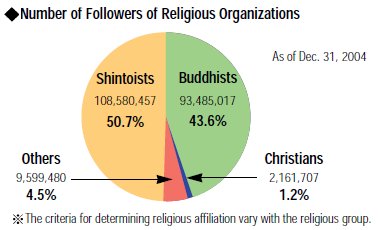

In 2003, over 300,000 Buddhist clergy attended to the needs of their flock, compared to around 80,000 Shinto clergy. Some 85% of Japan’s population claim to be Buddhists, with the largest group (around 25 million people) belonging to the Nichiren sect. However, the number of Japanese people claiming allegiance to either Shintoism or Buddhism exceeded 213 million, nearly 70% greater than Japan’s population of 127.5 million. This is puzzling, until one remembers that the Japanese find no problem claiming simultaneous allegiance to both sides.

This is easy to understand, for Shintoism and Buddhism flourished together (sharing deities and sacred grounds) for most of Japan’s recorded history. It was only in Japan’s Meiji Era (19th century) that the government forcibly separated the two camps, proclaiming Shintō to be the state religion (with the emperor a living god), and Buddhism to be a superstitious foreign import. Thankfully those militant days have passed. Modern Japan generally tolerates all faiths, and deities in the Shinto and Buddhist pantheons are worshipped again in tandem, as part of a unified set of protective spirits serving the nation.

Even so, the statistics are misleading. Since WWII, and the religious freedoms granted by Japan’s postwar constitution, the traditional Buddhist and Shinto sects have generated little enthusiasm among the people, and growth is stagnant. A recent survey by Zen’s Soto school found that nearly all people claiming a Buddhist affiliation could not name their sect's main temple or founder. Various government surveys reveal consistently that Japan’s population is indifferent to religion -- that the vast majority don’t practice Buddhism or Shintoism on any regular basis. Even though most families are affiliated with a Buddhist sect, this means little, for households were forced to declare an affiliation during the Edo era to help the government count the population and control tax registers.

Most Japanese visit shrines and temples as part of annual events and special rituals to commerate major life events, including the first shrine or temple visit of the new year (hatsumode), the annual visit to the family grave during the Buddhist Bon Festival, the first shrine visit for a newborn baby (miyamairi), the Shichi-Go-San (7-5-3) shrine festival for young chidren, Shinto wedding ceremonies, and Buddhist funerals.

Buddhism in Japan is associated primarily with funerals and rituals for the dead, and most Japanese learn about Buddhism only after someone dies in their family. As in the past, Japan’s existing temples and shrines, and their monks and nuns, pay no taxes.

Note on Terminology. When the Japanese first encountered the English word “religion” in the late 1850s, they had great difficulty translating the term it into Japanese, for there was no generic Japanese term that encompassed “all” the various doctrines and sects. For a time, the Japanese continued to use words like shū 宗 (sect, canon), kyō 教 (teachings), and ha 派 (sub-sect or faction) interchangeably for the various strands of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Christianity, and others. For a short time, “religion” was translated as “sect law” (shūhō 宗法) or “sect doctrine” (shūshi 宗旨). Ultimately, however, the Japanese settled on the term shūkyō 宗教 as the generic all-embrassing translation for “religion.” Thus, in modern-day Japan, Buddhism belongs to a universal group that also includes Judaism, Christianity, Taosim, Islam, etc. This is not mere word play. Scholar Jason Anada Josephson contents that it profoundly changed Japanese Buddhism in modern times. Citation below.

|

List Not Comprehensive

More entries to be added over time.

Most links jump to other pages.

A-TO-Z MENU

Sects Listed by Era Here

Main Forms of Buddhism

Theravāda 上座部仏教 (India)

Mahāyāna 大乗仏教 (India)

Vajrayāna 金剛乘 (India)

Vajrayāna is also known as Tantric or Esoteric Buddhism

Main Influences on Japan

Buddhism 仏教 (India)

Hinduism ヒンズー教 India

Confucianism 儒教 (China)

Taoism 道教 (China)

Shintōism 神道 (Japan)

Shugendō 修験道 (Japan)

BUDDHIST SECTS 仏教

Busshin 佛心宗 (Zen)

Dainichi 大日宗 (Shingon)

Hirosawa 広沢流 (Shingon)

Hokke 法華宗 (Nichiren)

Honganji 真宗本願寺 (Amida)

Hossō 法相宗 (Scholastic)

Ji-shu 時宗 (Amida)

Jōdo 淨土宗 (Amida)

Jōdo Shin 淨土眞宗 (Amida)

Jojitsu 成実宗 (Scholastic)

Jyūsanshū 十三宗 (13 Sects)

Kegon 華嚴宗

Kongōchō 金剛頂宗 (Shingon)

Kusha 倶舎宗 (Scholastic)

Mikkyō 密教 (Esoteric)

Nenbutsu 念佛宗 (Amida)

Nichiren 日蓮宗 (Lotus Sutra)

Ōbaku 黄檗宗 (Zen)

Onoryū 小野流 (Shingon)

Otani 真宗大谷派 (Amida)

Rinzai 臨濟宗 (Zen)

Ritsu 律宗 (Disciplinary)

Rokushū 六宗 Six Sects

Sanron 三論宗 (Scholastic)

Shingon 眞言宗 (Esoteric)

Shinnyo-en 真如苑 (Shingon)

Shōtoku 聖徳宗 (New)

Shugendō 修験道 (Ascetics)

Six Nara Schools 六宗

Sōtō 曹洞宗 (Zen)

Tendai 天台宗 (Imperial)

Thirteen Schools 十三宗

Yūzū Nenbutsu 融通念佛宗

Zen 禪宗

宗 Shū = suffix meaning school or sect. Shingon 眞言 is categorized as Mikkyō 密教 (Esoteric Buddhism). Tendai 天台 is also considered an Esoteric school.

SHINTŌ SECTS 神道

Jingū 神宮 (State Shintō)

Jinja 神社 (Shrine Shintō)

Kōshitsu 皇室 (State Shintō)

Kyōha 教派 (Sect Shintō)

Minzoku 民族 (Folk Shintō)

Ryōbu 両部 (Dual Shintō)

Shingon 眞言 (Dual Shintō)

Shinkō 新興 New Religions

Shūha 宗派 (Sect Shintō)

Yoshida Shintō 吉田神道

SHRINES BY KAMI

Asama 浅間 (Mt. Fuji)

Benzaiten 弁財天 (Wealth)

Hachiman 八幡宮 (Warriors)

Hie 日吉 (Tendai, Sannō)

Inari 稲荷 (Rice, Fox, Folk)

Ise 伊勢神宮 (State Shintō)

Mikumari Myōjin 子守明神

Sengen 浅間 (Children)

Suitengu 水天宮 (Children)

Tendai Sannō 天台山王

Tenjin 天神 (Deified People)

Ujigami 氏神 (Clan Specific)

|

|

Statistics on Japan’s Religious Organizations

Source: Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, Dec. 31, 2003

Source: Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, Dec. 31, 2004

|

|

|

Japan’s Main Buddhist Sects by Era

|

|

India

& Asia

–500 ~ +550

|

Japan

Asuka/Nara Era

+ 552 ~ 794

|

Japan

Heian Era

+ 794 ~ 1185

|

Japan

Kamakura Era

+ 1185 ~ 1333

|

Japan to

Present Day

+ 1334 ~ 2007

|

|

Buddhism originates in India around –500, and within 1000 years has spread across Asia. Read story here. It came last to Japan around +552; the mainstay form in Japan is Mahayana.

|

Main Sects:

Sanron

Hosso

Kegon

Ritsu

Jojitsu

Kusha

Shugendō

|

Main Sects:

Tendai

Shingon

Shugendō

Merging of

Buddhism and Shintoism

|

Main Sects:

Jōdo

Jōdo Shin

Nichiren

Zen Ritsu

Zen Soto

|

Main Sects:

Jōdo

Jōdo Shin

Nichiren

Zen Ritsu

Zen Soto

State Shinto

Imperial Shinto

New Shinto Sects

|

|

|

Great Age of Bronze Statuary, along with clay, dry lacquer, and wood.

|

Intro of Esoteric

sects and deities. Flowering of wood statues & mandala paintings. Great merging of Shinto and Buddhism.

|

New sects devoted to the commoner appear. Age of Mappo brings fears of hell. Wood statuary reaches zenith.

|

Secular art (folk art) supplants religious art. Buddhist statuary falls into decline. Zen arts prosper (e.g. calligraphy, tea rituals, gardening).

|

|

|

Court

Buddhism

Main Deities:

Shaka, Miroku, Kannon, Yakushi, Shitennō

|

Court

Buddhism

Main Deities:

Dainichi, Five Myō-ō, other Esoteric deities; mandala paintings

|

Commoner Buddhism

Main Deities:

Amida, Kannon, Jizō, Fudō Myō-ō, Daruma

|

Folk

Buddhism

Main Deities:

7 Lucky Gods, Amida, Kannon, Jizō, Fudō Myō-ō, Daruma, Kōbō Daishi, many others.

|

|

SECTS / SCHOOLS ARRANGED BY ERA

Guide to Japan’s Main Buddhist Sects

|

|

Buddhism in Asia

Before It Reaches Japan

Originating in India around –500, Buddhism swept quickly (some 1000 years) across mainland Asia, splitting into three main schools (Theravada, Mahayana, Vajrayana) as it evolved. It finally crossed the sea to Japan around +520-550 via Korea and later China, and spread quickly thereafter.

|

Before Japan

Overview (quite lengthy)

Theravada 上座部仏教

Mahayana 大乗仏教

Vajrayana 金剛乘

|

|

Asuka & Nara Eras +552-794

Six Schools of Nara Buddhism

Buddhism is introduced to Japan. Japan’s court favors Mahayana concepts. Prince Shōtoku becomes first imperial patron of Buddhism. Japan dispatches numerous missions to China and constructs many temples. Capital moves from Asuka to Nara (Heijōkyō 平城京) in +710. Six Schools of “Nara Buddhism” are introduced from Korea & China and compete for imperial patronage. Not much doctrinal innovation by these schools, which were largely academic, with their centers of study at seven main temples. Buddhism for nobility and court. Considered the Great Age of Gilt Bronze Statuary in Japan, with artwork imported mostly from Korea and China, or made by Korean and Chinese immigrants living in Japan.

|

Six Nara Schools

Overview

Hossō 法相宗

Jojitsu 成実宗

Kegon 華嚴宗

Kusha 倶舎宗

Ritsu 律宗

Sanron 三論宗

Seven Nara Temples

Academic centers of Buddhist study

Other Influences

Confucianism 儒教 (China)

Korean (Korea)

Shintō 神道 (Indigenous)

Shugendō 修験道 (Syncretic)

Taoism 道教 (China)

|

|

Heian Period +794-1185

Introduction of Tendai & Shingon

Introduction of Esoteric Buddhism

Great Age of Shinto-Buddhist Merger

Groundbreaking period in Japanese Buddhism. Called “Heian Buddhism,” it centered around the establishment of two new schools -- Tendai and Shingon -- both playing key roles in promoting Shinto-Buddhist syncretism. The two established their monasteries in mountain retreats away from the capital, which had moved to Kyoto (Heiankyō 平安京), thus gaining greater autonomy from the court. Both emphasized meditative practices, and taught that everyone had the potential to realize Buddhahood, not just the elite. Mandala artform flourishes, as does wood statuary. Multi-armed, multi-headed esoteric deities are introduced in great number, many with Shinto counterparts. Japan dispatches numerous missions to China during the period. Religious pilgrimages are instituted during the era. Native Shinto kami are considered manifestations of Buddhist divinities, and pilgrimages to dual Shinto-Buddhist sites are believed to bring double favor from both their Shinto & Buddhist counterparts. Despite greater common appeal, Buddhism remains mostly associated with court & nobility.

|

Two New Sects

Overview

Shingon 眞言宗

Tendai 天台宗

Two new sects, along with earlier Six Nara Schools, are known collectively as Eight Sects of Early Japanese Buddhism. Great period of Shinto-Buddhist syncretism, which lays groundwork for spread of Buddhism among masses in Kamakura era.

HONJI SUIJYAKU

Lit. merger of Buddhism and Shintoism.

Shingon Related

Mikkyo 密教 (Esoteric)

Dainichi 大日宗

Hirosawa 広沢流

Kongōchō 金剛頂宗

Onoryū 小野流

Syncretism

Ryōbu Shintō 両部

Shingon Shintō 真言

Shugendō 修験道 (Syncretic)

Tendai Shintō 天台

|

|

Kamakura Period +1185-1333

From Court to Commoner Buddhism

Major period of religious reform, with Buddhism focused on salvation of the illiterate commoner. Heian-era monasteries on Mt. Hiei (Tendai) and Mt. Koya (Shingon), plus earlier Six Schools of Nara, portrayed as materialistic, associated with land disputes, corrupted by their influence in court affairs, and involved in politically motivated warfare. Yet their branch temples dot the empire, giving them considerable power.

Nearly all the sects that have survived into the present day originated in Kamakura period, each breaking away from earlier schools. During the Kamakura era come the Jodō (or Pure Land sects) devoted to Amida Buddha, the Nichiren sect devoted to Kannon Bodhisattva, and the Zen sects and sub-sects, each largely developing upon older Chinese teachings, each expressing concern for the salvation of the ordinary person, each stressing pure and simple faith over complicated rites and doctrines. Prior to this, Buddhism was almost exclusively the faith of the court and upper classes. The Kamakura period is often viewed as the apogee of Buddhism’s development in Japan, since all major traditional sects gained great ground during this period. The Kamakura period also brings about an artistic flowering and greater realism in Buddhist statuary that some consider (myself included) the appex of Japan’s Buddhist art.

Zen was first brought to Japan by Eisai Zenji (1141-1215), who traveled to China in 1168 and 1187 and subsequently introduced the Rinzai (Chin. Lin-chi) lineage. The Soto (Chin. Ts'ao-tung) tradition was first propagated in Japan by Dogen Zenji (1200-1253), who traveled to China in 1223. Zen's general response to Mappo (The Age of the Degenerative Law) was to emphasize the importance of intensive meditative practice, which was believed to be the only way to overcome the negative influences of the age. By contrast, both the Pure Land sects (Jodō Shū) and Nichiren sects (Nichiren-shū) contended that people living in the age Mappo were too depraved and weak-willed to have any hope of securing salvation through their own efforts, and so they should rely on others to save them. For the Jodo Shū, this involves placing one's total faith in Amida (Skt. Amitabha) Buddha, while Nichiren taught his followers to rely solely on the Lotus Sutra (Skt. = Saddharma-pundarika-sutra; Jp. = Myoho-renge-kyo) and its focus on Kannon Bodhisattva, the God/Goddess of Mercy.

|

Kamakura Sects

Court to Commoner

Overview

Busshin 佛心宗 (Zen)

Hokke 法華宗 (Nichiren)

Ji-shu 時宗 (Amida)

Jodo Shin 淨土眞宗

Jodo 淨土宗 (Amida)

Nenbutsu 念佛宗 (Amida)

Nichiren 日蓮宗

Ōbaku 黄檗宗 (Zen)

Rinzai 臨濟宗 (Zen)

Sōtō 曹洞宗 (Zen)

Zen 禪宗

Yūzū Nenbutsu 融通念佛宗

shū 宗 (sect, canon), kyō 教 (teachings)

|

|

Thirteen (13) Schools of Japanese Buddhism

The number thirteen is rather arbitrary, but follows a tradition set earlier in China. During Japan’s Kamakura period 鎌倉 (+1185-1332), the Six Nara Schools and Two Heian Sects are eclipsed by the emegence of the Zen, Pure Land, and Nichiren sects, devoted to the commoner, which all rise to prominence in the subsequent Muromachi Period 室町 (+1392-1568; also known as the Ashikaga 足利 era), and today remain the mainstream of modern Japanese Buddhism. Because most of the 13 traditional sects originated during the Kamakura era (there were antecedents, to be sure), the Kamakura period is rightfully recognized by most scholars as one of religious reformation, one bringing Buddhism to the commoner.

Japanese 13 Schools

- Kegon 華嚴宗 (華厳経) (State)

- Hosso 法相宗 (唯識)

- Ritsu 律宗 (四分律) (Disciplinary)

- Tendai 天台宗 (Imperial)

- Shingon 眞言宗 (also Mikkyo 密教)

- Rinzai 臨濟宗 (Zen)

- Soto 曹洞宗 (Zen)

- Obaku 黄檗宗 (Zen)

- Pure Land (Jodo) 淨土宗 (Amida)

- Jodo Shin 眞宗 (Amida)

- Yuzu-nembutsu 融通念佛宗 (Amida)

- Ji 時宗 (Amida)

- Nichiren 日蓮宗 (Lotus Sutra)

Mikkyo 密教 = Esoteric Buddhism,

including both Shingon and Tendai

Chinese 13 Schools

- Satyasiddhi 成實宗

- Sanlun (Three Treatise) 三論宗

- Nirvana 涅槃宗

- Vinaya 律宗

- Dilun 地論宗

- Pure Land 淨土宗

- Chan (Meditation, Zen) 禪宗

- Shelun (Samgraha) 攝論宗 / 摂論宗

- Tiantai 天台宗

- Huayan 華嚴宗 華厳宗

- Faxiang 法相宗

- Esoteric (Vajrayana, True Word) 密宗

- Pítánzōng 毘曇宗 (Jp. = Bidonshū)

|

Jyūsanshū 十三宗

Lit. 13 Schools

|

|

Tokugawa Period to Present Day

The Tokugawa period (1600-1867) was a time of unprecedented power for Buddhism in Japan, but its success at the political level led to stagnation and apathy. When the warlord Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616) seized power in 1600, he initiated a violent persecution of Christianity, which had made significant numbers of converts in Japan. Viewing this as the thin end of the wedge of Western colonialism, he issued an edict requiring all Japanese to become officially affiliated with a Buddhist temple, and people were issued certificates (tera-uke) to this effect. Buddhist temples became part of the government bureaucracy and were required to keep records of births and deaths and also to aid the government's efforts to eradicate Christianity. This system, called danka-seido 檀家制度, was abolished in the Meiji period (1868-1912, during which Shinto became the state religion), but the bonds forged by the old system continue to maintain a sense of connection between many Japanese and their family temples. During the Tokugawa period, the number of Buddhist temples increased, as did the revenues from parishioners who were eager to avoid being suspected of harboring Christian sympathies. But this very success led to a situation in which the priesthood became lazy and corrupt, since there was no need for them to actively work to interest people in Buddhism. The Meiji restoration revived the old imperial cult, which identified the emperor as a living kami (a Shinto god), and a nationalistic form of Shinto became the state ideology. At the same time, Buddhism was considered a superstitious foreign import and suppressed. Because its public support had eroded due to its ossification and corruption, Buddhism suffered a general decline in popularity, which has persisted from World War II up to the present day.

|

Honganji 真宗本願寺 (Amida)

Otani 真宗大谷派 (Amida)

SHINTŌ SECTS 神道

Jingū 神宮 (State Shintō)

Jinja 神社 (Shrine Shintō)

Kōshitsu 皇室 (State Shintō)

Kyōha 教派 (Sect Shintō)

Minzoku 民族 (Folk Shintō)

Ryōbu 両部 (Dual Shintō)

Shingon 眞言 (Dual Shintō)

Shinkō 新興 New Religions

Shūha 宗派 (Sect Shintō)

Yoshida Shintō 吉田神道

New Religions

Shinnyo-en 真如苑

|

|

|

|

LEARN MORE

|

|