|

|

|

|

|

Jp. = Shishin 四神; Chn. = Sì Shòu 四獸

Four Guardians of the Four Compass Directions

Celestial Emblems of the Chinese Emperor

Shishin 四神. Also read Shijin. Also known in Japan

as the Shijū 四獣, Shishō 四象, or Shirei 四霊.

Origin = China

Click images to jump to specific creatures.

Tortoise (Black Warrior) = North, Winter, Black, Water

White Tiger (Kirin) = West, Fall, White, Metal

Red Bird (Phoenix) = South, Summer, Red, Fire

Dragon = East, Spring, Blue/Green, Wood

Each is associated with seven constellations. See 28 Constellations.

In Japan, the four creatures have

been supplanted by the SHITENNŌ

Lit. = Four Heavenly Kings (of Buddhism)

Four Guardians of the Four Compass Directions.

Associated closely with China’s Five Element Theory.

|

|

HISTORICAL NOTES

At the heart of Chinese mythology are four spiritual creatures (Sì Shòu 四獸) -- four celestial emblems -- each guarding a direction on the compass. In China, the four date back to at least the 2nd century BC. Each creature has a corresponding season, color, element, virtue, and other traits. Further, each corresponds to a quadrant in the sky, with each quadrant containing seven seishuku, or star constellations (also called the 28 lunar mansions or lodges; for charts, see this outside site). Each of the four groups of seven is associated with one of the four celestial creatures. There was a fifth direction -- the center, representing China itself -- which carried its own seishuku. In Japan, the symbolism of the four creatures appears to have merged with and been supplanted by the Shitennō (Four Heavenly Kings). The latter four are the Buddhist guardians of the four directions who serve Lord Taishakuten (who represents the center), and are closely associated with China’s Theory of Five Elements. In any case, the four animals are much more prevalent in artwork in China than in Japan, although in Japan one can still find groupings of the four creatures. The four were probably introduced to Japan from China sometime in the 7th century AD, for their images are found on the tomb walls at Takamatsuzuka 高松塚 in Nara, which was built sometime in the Asuka period (600 - 710 AD). They are also found on the base of the Yakushi Triad 薬師三尊像 at Yakushi-ji Temple 薬師寺, also in Nara.

SHISHIN 四神. Below Text Courtesy JAANUS

Ancient Chinese mythical animals associated with the four cardinal directions: green/blue dragon (Chn: Qinglong 青龍, Jp: Seiryuu) of the east; white tiger (Chn: Baihu 白虎, Jp: Byakko) of the west; red phoenix (Ch: Zhuque 朱雀, Jp: Suzaku) of the south; and black warrior (Chn: Xuan Wu 玄武, Jp: Genbu) of the north, a tortoise-like chimera with the head and tail of a serpent. The pictorial theme developed around the Warring States to Early Han period in China. Frequently painted on the walls of early Chinese and Korean tombs, the animals served primarily an apotropaic function warding off evil spirits. In Japan notable examples of the shishin are found on the walls of the tomb chamber in the tumulus Takamatsuzuka 高松塚 of the Asuka period, and on the base of the Yakushi Triad, Yakushi Sansonzō 薬師三尊像 at Yakushiji Temple 薬師寺, both in Nara.

Exerpt from “Chinese Mythology: Exerpt from “Chinese Mythology:

An Encyclopedia of Myth and Legend”

by Derek Walters. ISBN: 1855380803

Writes Walters: “The four directions, east, south, west and north, represent the four seasons, Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. Together with the Center, which in Chinese is synonymous with China itself, they form the five cardinal points. The Four Directions have been represented at least since the second century BC by four celestial animals, the Dragon for the East, the Bird for the South, the Tiger for the West, and the Tortoise for the North. Each animal has its own color: the Dragon is the Green of Spring, the Bird the red of Fire, the Tiger of Autumn the glittering white of metal (of ploughshares or swords), and the Tortoise Black, for night, or water. The four celestial animals, which have no connection with the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac, are also the names of the four divisions of the sky [note...each with seven constellations, see 28 Constellations]. The Dragon's Heart, the Pleiades, and the Bird Star are the names of three of the lunar mansions which marked the central position of the Dragon, Tiger and Bird. As there was no identifying star at the centre of the Black Tortoise, the appropriate place (the eleventh mansion) was called Void.”

Phoenix vs. Red Bird, Ch’i-lin (Kirin) vs. White Tiger. Why the Confusion ?

In the same book, Walters explains: “However, it seems that before the adoption of the Four Celestial Emblems, there were only three -- the Feng Bird (or Phoenix), the Dragon, and the Ch’i-lin (or unicorn). Bronze mirrors usually portray cosmological patterns and symbolism on the back. Those of the Tang period (618 - 906 AD) show all twelve, or sometimes the 28 or even 36 animals of the Chinese Zodiac, and those of an earlier period depict the four celestial emblems referred to above. But the very earliest mirrors show only the three: the Ch’i-lin, the Feng-huang, and the Dragon. Because of the astronomical significance, the White Tiger replaced the Ch’i-lin, and the Phoenix gave way to the Red Bird, which is of uncertain identity. Thus the Tortoise was a later but not the last addition, for many mystical texts refer to the northern constellation not as the tortoise, but as the Black Warrior.” < end quote from Derek Walters >

NOTE: The Chinese Ch’i-lin is known in Japan as KIRIN. Many web sites replace the White Tiger with the mythological KIRIN in groupings of the four animals. Many web sites also list the Phoenix, not the Red Bird, as the celestial emblem of the south. This confusion is entirely forgivable, as the composition of this group of four has changed over the centuries to reflect ever-changing traditions.

Attributes of the Four Attributes of the Four

China and Japan Myths and Legends

by Donald A. Mackenzie; ISBN: 1851700161

- Dragon. East, Spring, Wood, Planet Jupiter, liver & gall

- Red Bird (Phoenix). South, Summer, Fire, Planet Mars; heart and large intestines

- White Tiger. West, Autumn, Wind, Metal, Planet Venus, lungs and small intestine

- Tortoise. North, Black, Winter, Cold, Water, Planet Mercury, kidneys and bladder

EAST - THE DRAGON EAST - THE DRAGON

Jump to Main Dragon Page for More Details

Dragon; Ryū (Ryu) 龍 or Seiryū (Seiryu) 青龍 in Japan, Qinglong in China. A mythological animal of Chinese origin, and a member of the NAGA (Sanskrit) family of serpentine creatures who protect Buddhism. Japan’s dragon lore comes predominantly from China. Images of the reptilian dragon are found throughout Asia, and the pictorial form most widely recognized today was already prevalent in Chinese ink paintings in the Tang period (9th century). The mortal enemy of the dragon is the bird-man Karura and the Phoenix. Please visit the main DRAGON page to learn much more.

The dragon corresponds to the season spring, the color green/blue, the element wood, and the virtue propriety; supports and maintains the country (controls rain, symbol of the Emperor’s power). Often paired with the Phoenix, for the two represent both conflict and wedded bliss. In both China and Japan, Dragon and Phoenix symbolism is associated closely with the imperial family -- the emperor (dragon) and the empress (phoenix). The dragon corresponds to the season spring, the color green/blue, the element wood, and the virtue propriety; supports and maintains the country (controls rain, symbol of the Emperor’s power). Often paired with the Phoenix, for the two represent both conflict and wedded bliss. In both China and Japan, Dragon and Phoenix symbolism is associated closely with the imperial family -- the emperor (dragon) and the empress (phoenix).

Represents the yang principle; often portrayed surrounded by water or clouds. In Chinese mythology, there are five types of dragon: (1) the celestial dragons who guard the abodes of the gods; (2) dragon spirits, who rule over wind and rain but can also cause flooding; (3) earth dragons, who cleanse the rivers and deepen the oceans; (4) treasure-guarding dragons; and (5) imperial dragons, those with five claws instead of the usual four.

The dragon is a mythical creature resembling a snake -- reflecting its membership in the NAGA (Sanskrit) family of serpentine creatures. It is also a member of the Hachi Bushu (the eight protectors of Buddhism). Dragons are said to be shape shifters, and may assume human form. In contrast to Western mythology, dragons are rarely depicted as malevolent. Although fearsome and powerful, they are equally considered just, benevolent, and the bringers of wealth and good fortune. Click here for much more on the Asian dragon.

Editor’s Note. Despite the dragon’s close association with water and the watery realm, in the Shishin Grouping of Four Celestial Emblems (this page), the dragon is associated with the element WOOD. The turtle is associated with the element WATER. See Five Elements.

The Dragon’s seven constellations (seishuku 星宿; also read shōshuku or sukuyō 宿曜) are shown below. The Chinese term is Xīngsù 星宿 or Sù 宿, also written as Hsiu.

- Su Boshi

- Ami Boshi

- Tomo Boshi

- Soi Boshi

- Nakago Boshi

- Ashitare Boshi

- Mi Boshi

|

|

|

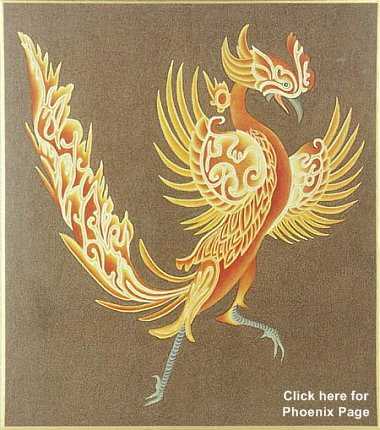

SOUTH -- THE SUZAKU (aka THE PHOENIX) SOUTH -- THE SUZAKU (aka THE PHOENIX)

Red Bird, Big Bird, Suzaku, Phoenix

Jump to Main Phoenix Page for More Details

Chinese = Zhū Qiǎo 朱雀 or Zhū Niǎo 朱鳥

Korean = Chujak 주작

Japanese = Suzaku, Sujaku, Shujaku 朱雀

Japanese = Shuchō 朱鳥 or Suchō, Akamitori, Akamidori; aka the Vermillion Bird. Shuchō was also a Japanese era name for a few months between 686 and 687 AD.

In Japan, the term “Suzaku” is translated as “Red Bird” or “Vermillion Chinese Phoenix.” In both Japan and China, the symbolism of the red bird seems nearly identical to or merged with that of the mythological Phoenix. At this site, I consider the Suzaku and the Phoenix to be the same magical creature, although I am not certain if this is entirely true. Scholar Derek Walters (see resources) says the Phoenix was supplanted (replaced) by the Red Bird, for the Red Bird more accurately reflected the astronomical iconography associated with the southern lunar mansions.

Corresponds to summer, red, fire, and knowledge; makes small seeds grow into giant trees (need to give source). Often paired with the dragon, for the two represent both conflict and wedded bliss; dragon (emperor) and phoenix (empress). Portrayed with radiant feathers, and an enchanting song; only appears in times of good fortune. Within the ancient Imperial Palace in Japan, there was a gate known as Suzakumon 朱雀門 (Red Bird Gate). See JAANUS for a few more details on this gate.

Suzaku’s seven seishuku 星宿 (constellations) are: Suzaku’s seven seishuku 星宿 (constellations) are:

- Chichiri Boshi (Chn. = Ching 井)

- Tamahome Boshi (Chn. = Kuei 鬼)

- Nuriko Boshi (Chn. = Liu 柳)

- Hotohori Boshi (Chn. = Hsing 星)

- Chiriko Boshi (Chn. = Chang 張)

- Tasuki Boshi (Chn. = Yi 翼)

- Mitsukake Boshi (Chn. = Chen 軫)

* Learn more about the Red Bird’s seven constellations (this site).

* See star charts for the Red Bird at this outside link.

The Red Bird of the South (Suzaku)

Found on tomb wall at Kitora Kofun

http://www2.gol.com/users/stever/kitora.htm

Photo courtesy Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Nara

Archaeological dating places its construction to the

Asuka period (7th to early 8th centuries)

Suzaku, The Red Bird, Modern Drawing. Available for Online Purchase

WEST - THE WHITE TIGER WEST - THE WHITE TIGER

Jpn = Byakko 白虎, Chn = Baihu. Guards Buddha’s teachings and mankind; observes world with clairvoyance; corresponds to the season fall, the color white, wind, the element metal, and the virtue righteousness. Says Donald Mackenzie: "The White Tiger of the West, for instance, is associated with metal. When, therefore, metal is placed in a grave, a ceremonial connection with the tiger god is effected. According to the Chinese Annals of Wu and Yueh, three days after the burial of the king, the essence of the element metal assumed the shape of a white tiger and crouched down on the top of the grave. Here the tiger is a protector - a preserver. As we have seen, white jade was used when the Tiger god of the West was worshipped; it is known as 'tiger jade;' a tiger was depicted on the jade symbol. To the Chinese the tiger was the king of all animals and lord of the mountains, and the tiger-jade ornament was specially reserved for commanders of armies. The male tiger was, among other things, the god of war, and in this capacity it not only assisted the armies of the emperors, but fought the demons that threatened the dead in their graves." <end quote>

The Tiger’s seven seishuku 星宿 (constellations) are: The Tiger’s seven seishuku 星宿 (constellations) are:

- Tokaki Boshi (Chn. = K’uei 奎)

- Tatara Boshi (Chn. = Lou 婁)

- Ekie Boshi (Chn. = Wei 胃)

- Subaru Boshi (Chn. = Mao 昴)

- Amefuri Boshi (Chn. = Pi 畢)

- Toroki Boshi (Chn. = Tsui 觜)

- Kagasuki Boshi (Chn. = Shen 參)

* Learn more about the Tiger’s seven constellations.

* See star charts for the White Tiger at this outside site.

PHOTO: From Research Report of Cultural Heritage in Asuka Village Vol. 3. A primary center of power in Japan in the 6th and 7th centuries, Asuka lies about 12 miles south of Nara in the Kinki District; home to many ancient temples and tombs. The Takamatsu Zuka Tombs 高松塚 were discovered the early 1970s and date back to Japan’s Asuka Period (600 - 710 AD).

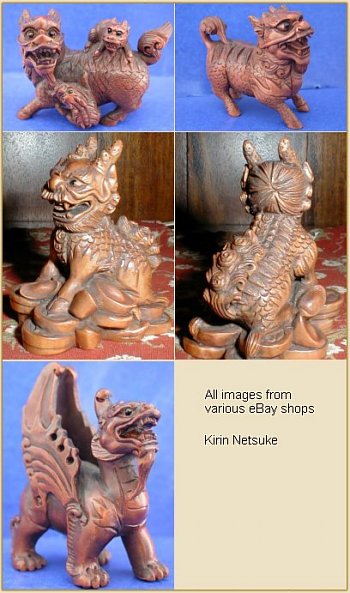

TIGER CONFUSED WITH KIRIN 麒麟

In Japan, the tiger is sometimes confused with the mythological Chinese Ch'i-lin (Qilin), which is rendered Kirin 麒麟 in Japan. Scholar Derek Walters says the Ch’i-lin was supplanted (replaced) by the White Tiger, for the Tiger more accurately reflected the astronomical iconography associated with the western lunar mansions.

KIRIN IN JAPAN

The Kirin, which often appears tiger-like in artwork (see photos below), is a different creature entirely from the White Tiger. The Kirin is said to have the body of a deer, the tail of an ox, the hooves of a horse, a body covered with the scales of a fish, and a single horn. The Kirin appears only before the birth or death of a great and wise person. Said to live in paradise, the Kirin personifies all that is good, pure, and peaceful; can live to be 1,000 years old. The Kirin, which often appears tiger-like in artwork (see photos below), is a different creature entirely from the White Tiger. The Kirin is said to have the body of a deer, the tail of an ox, the hooves of a horse, a body covered with the scales of a fish, and a single horn. The Kirin appears only before the birth or death of a great and wise person. Said to live in paradise, the Kirin personifies all that is good, pure, and peaceful; can live to be 1,000 years old.

Below text courtesy of thefreedictionary.com

A mythical horned Chinese deer-like creature said to appear only when a sage has appeared. It is a good omen associated with serenity and prosperity. Often depicted with what looks like fire all over its body. In most drawings, its head looks like that of a Chinese dragon (see dragon above). Japanese art typically depicts the Kirin as more deer-like than its Chinese counterpart. Kirin is sometimes translated in English as "unicorn," because it looks similar to the unicorn -- the later a hoofed mythological horse-like beast with a single horn on its head. Some accounts describe it as having the body of a deer and the head of a lion. <end quote> A mythical horned Chinese deer-like creature said to appear only when a sage has appeared. It is a good omen associated with serenity and prosperity. Often depicted with what looks like fire all over its body. In most drawings, its head looks like that of a Chinese dragon (see dragon above). Japanese art typically depicts the Kirin as more deer-like than its Chinese counterpart. Kirin is sometimes translated in English as "unicorn," because it looks similar to the unicorn -- the later a hoofed mythological horse-like beast with a single horn on its head. Some accounts describe it as having the body of a deer and the head of a lion. <end quote>

Below: Images of the Kirin

NORTH - The Tortoise / Turtle / Snake NORTH - The Tortoise / Turtle / Snake

Genbu 玄武 in Japanese; in Chinese Gui Xian, Kuei Hsien, Zuan Wu, Zheng Wu, Xuanwu. Genbu is always listening, and is thus portrayed as completely versed in Buddha’s teachings; corresponds to winter, cold, water, black, earth, and faith. The tortoise is a symbol of long life and happiness. When it becomes one thousand years old, it is able to speak the language of humans. Able to foretell the future. In artwork, often shown together with the snake.

In Japan, the turtle’s Buddhist counterpart is known as Tamonten, the most powerful of the Shitennō (Four Buddhist Protectors of the Four Directions). Tamonten is also known as the Black Warrior and is also called Bishamonten; like the tortoise, his imagery corresponds to north, winter, black, and the element water. In Japan, the turtle’s Buddhist counterpart is known as Tamonten, the most powerful of the Shitennō (Four Buddhist Protectors of the Four Directions). Tamonten is also known as the Black Warrior and is also called Bishamonten; like the tortoise, his imagery corresponds to north, winter, black, and the element water.

Says Derek Walters: "One of the Celestial Emblems, the symbol of longevity and wisdom. It is said that its shell represents the vault of the universe. A common symbol for longevity is the Tortoise and Snake, whose union was thought to have engendered the universe. The reason why tortoise symbolism has been superseded by the Black Warrior as the emblem of the North, is probably due to the fact that 'tortoise' is a term of abuse in China." <end quote by Walters>

Turtle as Term of Abuse in China. In China, the term “turtle egg” is equivalent to calling someone a “bastard.” The reasoning is simple. Turtles crawl out of the ocean, dig a hole in the sand, and with their backs to the hole, they lay their eggs. The turtle then pushes the sand back over the eggs and returns to the ocean. The eggs are left to fend for themselves. Furthermore, islanders can stand behind the turtle as it lays its eggs and catch the eggs in their hands. The turtle does not even notice. The turtle fills the empty hole -- never once looking back -- and returns to the ocean. Turtle as Term of Abuse in China. In China, the term “turtle egg” is equivalent to calling someone a “bastard.” The reasoning is simple. Turtles crawl out of the ocean, dig a hole in the sand, and with their backs to the hole, they lay their eggs. The turtle then pushes the sand back over the eggs and returns to the ocean. The eggs are left to fend for themselves. Furthermore, islanders can stand behind the turtle as it lays its eggs and catch the eggs in their hands. The turtle does not even notice. The turtle fills the empty hole -- never once looking back -- and returns to the ocean.

Says Donald Mackenzie: "In China the tortoise had divine attributes. Tortoise shell is a symbol of unchangeability, and a symbol or rank when used for court girdles. The tortoise was also used for purposes of divination. A gigantic mythical tortoise is supposed, in the Far East, to live in the depths of the ocean. It has one eye situated in the middle of its body. Once every three thousand years it rises to the surface and turns over on its back so that it may see the sun." <end quote Mackenzie>

A turtle’s shell (plastron) also symbolizes a suit of armor, hence the turtle is also called the Black Warrior or Dark Warrior. The Dark Warrior represents the Northern Palace or northern constellations of the Chinese zodiac. Genbu’s seven seishuku 星宿 (constellations) are:

- Hikistu Boshi (Chn. = Tou 斗)

- Inami Boshi (Chn. = Niu 牛)

- Uruki Boshi (Chn. = Nü 女)

- Tomite Boshi (Chn. = Xū 虚)

- Umiyame Boshi (Chn. = Wei 危)

- Hatsui Boshi (Chn. = Shih 室)

- Namame Boshi (Chn. = Pi 璧)

|

|

|

Tortoise and Snake Symbolism

Below text courtesy Gabi Greve

- Tortoise and Snake 亀と蛇

In Chinese culture, especially under the influence of Taoism (道教) the tortoise is the symbol of heaven and earth, its shell compared to the vaulted heaven and the underside to the flat disc of the earth. The tortoise was the hero of many ancient legends. It helped the First Chinese Emperor to tame the Yellow River, so Shang-di rewarded the animal with a life span of Ten Thousand Years. Thus the tortoise became a symbol for Long Life. It also stands for immutability and steadfastness.

We often see stone grave steles on a stone tortoise or reliquaries standing on it. The tortoise is also regarded as an immortal creature. As there are no male tortoise -- as the ancient believed -- the female had to mate with a snake. Thus the tortoise embracing a snake became the protector symbol of the north, but since the word "tortoise" was taboo in Chinese, it was referred to as the "dark warrior" (genbu 玄武 ) and finally became Zhenwu (in Chinese Taoism), one of the four protector gods of the four directions. The symbol of Zhenwu, the Protector God of the North, as tortoise and snake (or tortoise entwined by a snake) dates back to the third century BC. For more on Taoism, see this online catalog about "Taoism and the Arts of China."

- Tsurukame 鶴亀 - Tortoise and Crane

The crane lives 1,000 years and the tortoise 10.000, says a Japanese proverb. Both animals are symbols of longevity. The connection between a tortoise and a crane also dates back to China. The crane too was a symbol of Long Life and also the symbol of the relationship of Father and Son according to the Confucian philosophy. Furthermore the crane is a symbol of wisdom. When a high-ranking Taoist priest died, it was said he was "turning into a crane." In Japanese Buddhist art, we have a candle holder in the form of a crane standing on a tortoise (tsurukame shokudai 鶴亀燭台). This kind of temple decoration was often used by the New Sect of the Pure Land (Jodo Shinshuu 浄土真宗). Usually the crane was carrying a lotos flower with a long stem in his mouth and the flower was formed in a way to hold the candle. These types of illumination stands were produced since the Muromachi Period (1333 - 1573 AD). <end quote from Gabi Greve>

|

Tomb with Turtle Body with Snake Head

|

|

Tomb of Oe Hiromoto (in Kamakura; 1225 AD). Oe was Yoritomo Minamoto’s celebrated counselor during the founding of the Kamakura Shogunate. He was a distinguished scholar credited with conceiving and organizing the Kamakura system. Another nearby tomb, with similar turtle / snake design, is that of Shimazu Tadahisa, the illegitimate son of Yoritomo.

|

|

MORE ON THE BLACK WARRIOR

The Chinese Dark Lord of the North - Xuan Wu

Below Text Courtesy of: The Online Journal of the I Ching, Yi Jing

The Dark Lord of the North (Xuan Wu Da Di) is a deity that comes from the pre-history of shamanic times (c. 6000 BC). In relatively modern Chinese prehistory (c. 1200 BC) the Dark Lord has become the human figure of a warrior with wild, unruly black hair, dressed in the primitive clothing of the tribal peoples of Neolithic times. He is powerful and strong deity capable of powerful punishments and redemptive deliverance. He is frequently depicted as the black tortoise who rules over the direction North in Chinese cosmology. He is called " Xuan" for the color black and " Wu" meaning "tortoise.

Prehistory: The Snake and the Tortoise

The Dark Lord speaks to a more ancient myth, that of the snake and the tortoise, in religious prehistory. Very ancient drawings of a black snake and tortoise together symbolize the Dark Lord. These reptilian creatures, the snake and tortoise, were probably themselves worshipped or were powerful medicine to help in overcoming one's enemies. From Shang times onward, the flag bearing this symbol (snake and tortoise) was part of the king's color guard. In Neolithic prehistory the tortoise -- also known as the somber warrior -- and snake together are the symbols or totems of a powerful shaman who fights evil against the demons of the Invisible World. According to ancient tradition, the black tortoise is yin; the snake yang. <end quote by Online Journal of the I Ching>

TURTLE PROVERB TURTLE PROVERB

Old Chinese spelling; pronounced “kame” in Japan; means turtle. PROVERB: The rareness of meeting a Buddha is compared with the difficulty of a blind sea-turtle finding a log to float on, or a one-eyed tortoise finding a log with a spy-hole through it." [from soothill]

TURTLE IN EARLY INDIA, BUDDHST LEGENDS, JATAKA

Below text courtesy www.borobudur.tv/avadana_04.htm

The story of the Historical Buddha’s birth as a tortoise (in his past lives, before becoming the Buddha) is featured in Indian reliefs of the first gallery balustrade, where a total of five panels present the culminating scenes from a story called the Kaccapavadana. In the Hindu scriptures, the great sage Kasyapa (Sanskrit for toroise) is the father of Aditya, the Sun. The solar nature of Kasyapa is particularly appropriate representation for a past life of the Sakyamuni, who was sometimes called the "Kinsman of the Sun" (Adityabandu).

India, circa 191-195 AD

See www.borobudur.tv/avadana_04.htm

CENTER, Synonymous with China itself

Tenkyoku (Chinese = Pangu, Pan Ku, P’an Ku).

Associated with virtue of benevolence. The seishuku (constellations) are:

- Taishi Boshi

- Tei Boshi

- Shoshi Boshi

- Koukyuu Boshi

- Kyoku Boshi

- Shiho Boshi

- ????

P’an Ku P’an Ku

Exerpt from “Chinese Mythology: An Encyclopedia

of Myth and Legend” by Derek Walters, ISBN: 1855380803

The legendary architect of the universe. Oddly enough, the story of how P’an Ku created the universe is now so firmly established in Chinese folklore, it would be forgivable to assume that the story of P’an Ku was one of China’s earliest legends. However, the great philosopher Ssu-ma Ch’ien makes no mention of it, and in fact P’an Ku does not make his appearance until the 4th century AD. The legend, ascribed to the brush of Ko Hung (Kung) is likely to have been a tale imported from Southeast Asia. It is highly unlikely that it would have been fabricated by a Taoist writer such as Ko Kung, because it would have been second-nature to an educated Chinese writer to introduce established characters of Chinese mythology, but none are present. The date of its composition may be even later, as its first appearance may not be earlier than the 11th century Wai Chi (Records of Foreign Lands). The substance of the legend is that P’an Ku chiselled the universe for eighteen thousand years, and as he chiselled, so he grew himself, six feet every day. When his work was complete, his body became the substance of the universe: his head became the mountains, his breath the wind. From his eyes the sun and moon were made, while the stars were made from his beard. His limbs became the four quarters, his blood the rivers, his flesh the soil, his hairs the trees and plants, his teeth and bones the rocks and minerals, and his sweat the rain. Finally, the lice on his body become the human race. In China, he holds the hammer and chisel with which he formed the universe, and is surrounded by the Four Creatures (tortoise, phoenix, dragon, and unicorn. <end quote by Derek Walters >.

Pangu (Chinese Adam) & the Four Mythical Creatures

Text courtesy www.chinavoc.com/history/ancient/legend.htm

China has a history longer than that of any other present day nation. We have plenty of myths and legends. The first figure in our history is Pangu, regarded as the Chinese Adam by westerners. According to legend, in the beginning there was only darkness and chaos. Then an extremely large egg appeared. This vast egg was subjected to two opposing forces or principles. The interaction of the two forces -- yin, the passive or negative female principle, and yang, the active or positive male principle -- caused the egg to produce Pangu, and the shell to separate. The upper half of the shell formed the heaven, and the lower half the earth.

Pangu has been depicted in many ways. He sometimes appears as a dwarf with two horns on his head, clothed in skin or leaves. He may be holding a hammer in one hand and a chisel in the other, or perhaps the symbol of yin and yang. He may also be shown holding the sun in one hand and the moon in the other. He is often depicted with his companions the four supernatural animals - the phoenix, the dragon, the unicorn and the tortoise. In any case, Pangu grew rapidly and increased his height by six to ten feet daily. He hammered and chiseled a massive piece of granite floating aimlessly in space, and as he worked, the heavens and the earth became progressively wider. He labored ceaselessly for eighteen thousand years and finally he separated heaven from earth. His body dissolved when his work was done.

LEARN MORE

- 28 Constellations, 28 Moon Lodges, 28 Moon Stations

This site. Learn more about each of the four quarters (north, south, east, west) and the seven constellations in each group. All 28 represent points in the moon’s monthly path, and each was deified.

Chinese Mythology: Encyclopedia of Myth and Legend Chinese Mythology: Encyclopedia of Myth and Legend

By Derek Walters. A-to-Z format. Very useful resource, but no Chinese language characters are given, only English equivalents. First published by The Aquarian Press, 1992. Pages = 191 pages. ISBN = 1855380803.

- China and Japan Myths and Legends

by Donald A. Mackenzie. Publisher: Bracken Books (1986). ISBN: 1851700161

- Star Charts & Moon Stations, by Steve Renshaw and Saori Ihara

Detailed maps of the 28 Lunar Mansions. A very excellent resource. For other charts of the 28 Lunar Mansions, see www.sempai.org

- Takamatsu Zuka Tombs 高松塚 & Kitora Kofun Tombs

An Ancient View of the Sky from a Tomb in Asuka, Japan

By Steve Renshaw and Saori Ihara

http://www2.gol.com/users/stever/kitora.htm

http://www2.gol.com/users/stever/asuka.htm

http://www2.gol.com/users/stever/charts.htm

- Kelley L. Ross, Ph.D., Los Angeles Valley College

www.friesian.com/elements.htm (Excellent review)

- Tsurukame -- Crane, Tortoise and Snake Symbolism

Dr. Gabi Greve darumamuseum.blogspot.com/2010/02/tsurukame.html

- Dolores Kozielski

Certified Feng Shui consultant who practices in NJ & PA.

www.fengshuiwrite.com

- Wonderful Site for Textual Info on Buddhism

campross.crosswinds.net/ShuteiMandala/4kings.html

- Four Animals, espeicially the KIRIN

www.chartpak.com/pelikan/kirin_story.html

- Says Phoenix is Karura (which I believe is wrong)

www.boadicea.net/saintseiya/ikki/mythology.htm

- Astrology: More on Chinese Constellations & Calendar

www.pp.htv.fi/ivilkki/Chinese_Calendar_and_Astrology.html

Modern reproductions of old Chinese imagery.

Photo from this Japanese eStore.

Modern Artwork of the Four. Photo courtesy daiwagroup.com/fengshui/

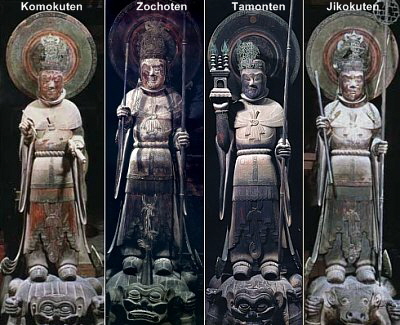

SHITENNŌ. Lit. = Four Heavenly Kings (Buddhist)

Four guardians of the four compass directions in Buddhism. Associated closely with China’s Five Element Theory. The four celestial emblems (dragon, red bird, tiger, turtle) can be associated with the iconography of the Shitennō, who also guard the four cardinal directions.

Four Shitennō, Horyuji (Hōryūji) Temple 法隆寺, Nara

Mid-7th Century. Oldest extant set of the four.

Kōmokuten 広目天, Zōchōten 増長天, Tamonten 多門天, Jikokuten 持国天

Painted Wood, Each Statue Approx. 133.5 cm in Height

Photos from Comprehensive Dictionary of Japan's Nat’l Treasures

国宝大事典 (西川 杏太郎. ISBN 4-06-187822-0.

ū ā ō Ō Ū

|

|