|

|

|

|

THIS IS A SIDE PAGE

Return to Main Inari & Fox Page

稲荷 Inari

INARI or Oinari or Oinari-sama

Shinto God/Goddess of Rice & Food

Messenger = The Fox (Kitsune)

狐 = Kitsune

INARI = Shinto Rice Kami

by Becky Yoose (University of Wisconsin - Eau Claire)

www.uwec.edu/philrel/shimbutsudo/inari.html

Inari is one of the most well known kami in popular folk Shinto. He (or she) is the god of rice and is related with general prosperity. In earlier Japan, Inari was also the patron of sword smiths and merchants. Primarily, however, Inari is associated with agriculture, protecting rice fields and giving the farmers an abundant harvest every year. One of the main myths concerning Inari tells of this kami coming down a mountain every spring when it is planting season and ascending back up the mountain after the harvest for the winter. Both events are celebrated in popular folk festivals (Herbert 506).

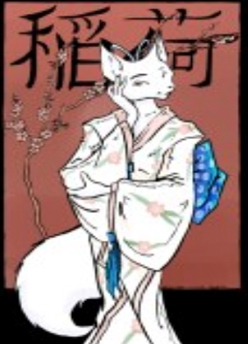

Inari does not have one main image or gender, but rather has many associated images and is identified with other kami as well. Usually when one refers to Inari the two general images are of an old man sitting on a pile of rice with two foxes beside him, or of a beautiful fox-woman. Inari does not have one main image or gender, but rather has many associated images and is identified with other kami as well. Usually when one refers to Inari the two general images are of an old man sitting on a pile of rice with two foxes beside him, or of a beautiful fox-woman.

The kami directly identified with Inari are quite numerous. First is Hettsui-no-Kami, the Goddess of the Kitchen Range. During the Feast of the Bellows, where fires are lit, Inari is included among the deities honored, together with Hettsui-no-Kami; indeed, the two are said to be one and the same (Coulter and Turner, 237). In earlier times, Inari was thought of as being three (or sometimes five) kami. Among the kami that Inari has been associated with are Miketsu Okami, Ogetsu Hime no Kami, Ukanomitama no Kami, Toyouke Hime no Kami, and Toyouke no Kami. Yet more kami once linked with Inari were Ninigi no Mikoto, Susano-O no Mikoto, and both Izanami and Izanagi no Mikoto (Smyers 153).

There are two Buddhist versions of Inari as well. One version is the Chinjugami, the temple protector. While this form is more common, another version, named Dakiniten, is the one worshiped as the primary deity. The name “Dakiniten” is derived from the Sanskrit work “dakini,” meaning a “space-goer” or “celestial goddess.” It refers to one of the legendary incarnations in which the Buddha appeared (prior to being born as Shakyamuni), when he lived as a bodhisattva and served unselfishly to promote the enlightenment of others. This Dakini later merged in the popular imagination of Japan with the fox-benefactress who brought food to all the people. The fall festival at Toyokawa Inari shrine would involve Dakiniten (Smyers 7). Interestingly, the linkage between Toyokawa and Inari-Dakiniten may have begun on account of the foxes associated separately with each of these food goddesses. On the other hand, many scholars believe that Toyokawa and Inari have always been one and the same (Smyers 38).

Another kami identified with Inari is Uke-mochi, the Shinto goddess of food. According to a myth recorded in the Nihongoki, Uke vomited rice and fish to give to Tsukiyomi, the Moon Kami, at a banquet. (This may have symbolized the eternal recycling of food from one life form to another.) In any case, Tsukiyomi apparently did not appreciate the gesture, for he killed Uke instantly. Her dead body then produced all the foods and animals that are related to agriculture. (For a fuller description of this myth, see Tsukiyomi.) According to some accounts, Uke-mochi was also said to have been married to Inari before she was killed. When she died, Inari took over her role (Nihongi 32).

The fox (kitsune in Japanese) is closely associated to Inari. However, many people mistake the kitsune for the actual kami. This error should be avoided, for the fox is merely Inari’s messenger and servant. These animals are believed to help protect the rice crops and help people in general. Some folk stories, however, portray the kitsune as tricksters and wicked animals. An example of a benign kitsune comes from a story recounted in The Fox and the Jewel about a mother whose child fell out the window of her second-story home. Astonishingly, the child landed unhurt in the yard below, though surrounded by shards of broken glass. A few years later the mother learned from an ascetic (who had no prior knowledge of the incident) that Inari had saved her daughter by having a fox-spirit catch her in its mouth and place her on the ground unhurt (Smyers 107).

Kitsune

(Oinari’s Messenger)

Photo

Fox at Tsurugaoka

Hachimangu Shrine

Kamakura City

Photo by

Mark Schumacher

|

|

There are several theories on how the kitsune became Inari’s servant. The first is a myth in a Buddhist text from the 14th century telling of a family of foxes who traveled to the shrine at Inari Mountain to offer their service to Inari. Inari granted their request and placed them as the attendants of the shrine (Smyers 80). Another theory comes from the behavior of actual living foxes. Foxes are often seen in and around rice fields during the growing season eating the rodents that would otherwise consume the rice. This pattern of behavior gave them the image of guardians of the fields (Smyers 75). Also significant is that the color of the fox resembles the color of ripened rice, and its tail looks like a full sheaf of rice. These traits help to explain how the kitsune came to be associated with an agricultural deity like Inari in the early years of Inari worship (beginning around the eighth century).

Another way of explaining the fox connection derives it from representations of the Buddhist Bodhisattva Dakiniten, who is often shown carrying rice on a flying white fox. This image, along with ancient Dakiniten sorcery involving fox replicas, may have led to the eventual connection of Dakiniten to Inari and the fox association that came with it (Smyers 84).

A jewel is also associated with Inari. Wish-fulfilling jewels are usually found on most fox statues in Inari shrines either in its mouth or under the paw (Smyers 112). These jewels represent spiritual and material wealth, fertility, and life; the types of things that are associated with prosperity. The fox holes in the shrines are jewel-shaped in their openings, providing another connection between the wish-granting jewels and tutelary fox-spirits (Smyers 146).

Inari shrines are everywhere. One out of three Shinto shrines is dedicated to Inari (Smyers 1). The most popular Shinto Inari shrine is Fushimi Inari Shrine in southern Kyoto. Since the eighth century, Inari has been worshiped here by the mountain with the same name. This shrine, unlike the undecorated shrines of other kami, has up to ten thousand red torii (sacred gates) lining a 2.5-mile-long path in the back of the shrine. One can also find stone foxes that serve as the image of Inari’s messengers, some with the traditional fried tofu offerings at their feet (Herbert 506, also see Smyers 74). Another Inari shrine that is popular is the Buddhist Toyokawa Inari Shrine, or Myogonji Temple. Here we find Inari Dakiniten as the main object of worship (Smyers 34). Instead of bright red torii, this temple has rows of red and white prayer flags. As one priest said, “Priests should live simply and not flaunt wealth, and the temple should reflect this idea too” (Smyers 36).

Toyokawa Inari Shrine -- Fox Statues

Why the Red Bibs? Click here to find out.

Comment: Inari is indeed one of the more mysterious kami in Shinto. While researching for this paper I found many different (even conflicting) views on this deity of rice.The Fox and the Jewel recounts an episode involving a priest at the Fushimi shrine who commented on this diversity: “If there were one hundred worshipers, they will have one hundred different ideas about Inari” (156). With that one hundred, two things are clear: Inari is connected with rice and foxes. The rest is up to the believer. As mentioned before, Inari itself has two main images and is even worshiped as other deities such as Uke-mochi. Trying to pin down a definite and unambiguous meaning for Inari would be like asking different groups of people to define universal ideas like truth and beauty. People may share a few parts of their meaning; however each interpretation is unique to the individual believer. Inari is such an idea, having its variations among many. To try to see Inari just as the Old Man of Rice or just as Dakiniten, would be to overlook the diversity that is imbedded in Inari. In order to study Inari, one has to look beyond any one representation in order to have a well-rounded view of this kami.

For more information about the history and contemporary worship of Inari, The Fox and the Jewel by Karen Smyers is especially recommended.

Inari, wood figurine, Tokugawa Period (1603-1867)

Courtesy Musée Guimet, Paris, where figurine is located.

Sources

Coulter, Charles R. and Patricia Turner. Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland Co. Inc., 2000.

Herbert, Jean. Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan. New York, Stein and Day, 1967.

Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Translated by W.G. Aston. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1956.

Smyers, Karen A. The Fox and the Jewel: Shared and Private Meanings in Contemporary Japanese Inari Worship. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999.

THIS IS A SIDE PAGE

Return to Main Inari & Fox Page

|

|