Buddha Statues & Japan – Jan. 2012

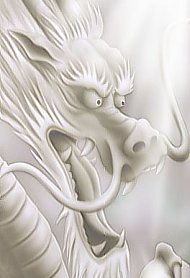

Welcome 2012 — Year of the Dragon

Befittingly for the Year of the Dragon, this issue begins with a tribute to the dragon in Japanese mythology and art, and provides handy links to the A-to-Z Photo Dictionary for those who want to explore dragon lore more deeply. It also features a book review (by me) that appeared in the January/February 2012 edition of Orientations, a highly respected magazine read by collectors, connoisseurs, art historians, and scholars of Asian art. Orientations’ first issue of 2012 traces the origins and evolution of the dragon motif in ceramics of China’s Yuan dynasty (mid-14th century).

INTRODUCTION. Dragon 龍 (Lóng = China, Ryū = Japan). In Asia, the dragon appeared in Chinese myth & artwork well before the introduction of Buddhism to China in the 1st & 2nd centuries CE. Japan’s dragon lore comes predominantly from China. Images of the creature are found throughout Asia, where it was adopted as a protector of Buddhism, a symbol of imperial power, the guardian of the east, the controller of rain and tempests, and a magical shape shifter able to assume human form and mate with people. In contrast to Europe’s malevolent dragon, the Asian dragon is considered benevolent, just, and the bringer of wealth. Learn more at the A-to-Z Photo Dictionary.

|

|

|

|

One of Four Celestial Emblems, each guarding a compass direction (dragon = east, red bird = south, tiger = west, tortoise = north). Each is linked to a season, color, element, & |

One of the 12 Zodiac Signs. Patron of those born in |

Each of the 12 Zodiac creatures is also associated |

|

|

|

|

Dragon images are commonly placed under the eaves of Japanese temples & shrines to ward off evil spirits, as are images of the shishi (lion) and baku (nightmare eater). |

Dragons are often painted |

From the medieval period |

|

|

|

|

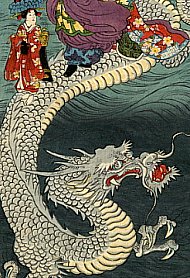

Dragons are the messengers and avatars of Benzaten, Japan’s goddess of water, art, music, & learning. This topic will be explored in-depth this Feb. at the A-to-Z Dictionary. |

Dragons are also closely associated with Kannon (Goddess of Mercy), kami Shirayamahime, and other deities in the Buddhist & Shinto pantheons of Japan. |

Carp transforming into dragon. Among countless dragon stories in China & Japan, one of the |

Chinese Legend of Carp Becoming a Dragon

A common artistic theme from old China, one based on a Chinese legend known as Koi-no-Takinobori in Japan, wherein carp swim, against all odds, up a waterfall known as the “Dragon Gate” at the headwaters of China’s Yellow River. The gods are very impressed by the feat, and reward the few successful carp by turning them into powerful dragons. The story symbolizes the virtues of courage, effort, and perseverance, which correspond to the nearly impossible struggle of humans to attain Buddhahood. In modern Japan, temples and shrines commonly stock their garden ponds with carp, which grow to enormous sizes in a variety of colors.

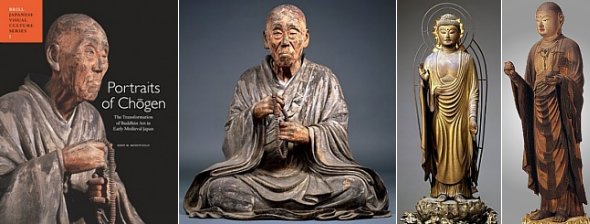

Book Recommendation, Book Review

To order the book online, see Brill Publications. To read the book review, click here.

To order the book online, see Brill Publications. To read the book review, click here.